Abstract

Since the beginning of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic, antibody responses and antibody effector functions targeting SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells have been understudied. Consequently, the role of these types of antibodies in SARS‐CoV‐2 disease (COVID‐19) and immunity is still undetermined. To provide tools to study these responses, we used plasma from SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals (n = 50) and SARS‐CoV‐2 naive healthy controls (n = 20) to develop four specific and reproducible flow cytometry‐based assays: (i) two assessing antibody binding to, and antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation against, SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells and (ii) two assessing antibody binding to, and antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation against, SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike‐transfected cells. All four assays demonstrated the ability to detect the presence of these functional antibody responses in a specific and reproducible manner. Interestingly, we found weak to moderate correlations between the four assays (Spearman rho ranged from 0.50 to 0.74), suggesting limited overlap in the responses captured by the individual assays. Lastly, while we initially developed each assay with multiple dilutions in an effort to capture the full relationship between antibody titers and assay outcome, we explored the relationship between fewer antibody dilutions and the full dilution series for each assay to reduce assay costs and improve assay efficiency. We found high correlations between the full dilution series and fewer or single dilutions of plasma. Use of single or fewer sample dilutions to accurately determine the response rates and magnitudes of the responses allows for high‐throughput use of these assays platforms to facilitate assessment of antibody responses elicited by SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and vaccination in large clinical studies.

Keywords: antibody, binding, infected cell, NK cell degranulation, SARS‐CoV‐2

1. INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) was caused by infection with an emergent coronavirus, SARS‐CoV [1], which was most likely generated through sequential recombination and zoonosis [2]. SARS lung pathology studies revealed that alveolar damage was often associated with the presence of multinucleated giant cells, postulated to be a result of syncytia formation [3, 4]. Syncytia can form when Spike (S) protein that is not assembled into virions inside the endoplasmic reticulum‐Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) is expressed on the plasma membrane, and interacts with its entry receptor on neighboring cells [5, 6]. SARS‐CoV‐2, the virus responsible for the COVID‐19 pandemic [7], utilizes the same cellular receptor (ACE2) for entry into host cells as SARS‐CoV [8], and is thought to replicate similarly. Giant multinucleated cells have also been observed in pulmonary pathology of individuals with COVID‐19 [9]. It is therefore likely that SARS‐COV‐2‐infected cells can promote direct cell‐to‐cell spread of the virus through syncytia formation, providing a rationale for studying immune responses targeting infected cells.

A large amount of effort has been spent in developing assays that can identify the presence of binding and neutralizing antibody responses against SARS‐CoV‐2, and a large body of literature has been generated characterizing the levels of these antibody functions after infection or vaccination. Although antibody Fc‐mediated functions could be effective responses against COVID‐19 [10, 11, 12, 13], we are still facing a significant gap in knowledge on the role of Fc‐mediated antibody responses against coronaviruses (CoV), including SARS‐CoV‐2. The ability of antibodies to bind seasonal CoV‐infected cells and mediate antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) was reported over 30 years ago in a small study [14], with follow‐up research for SARS‐CoV‐2 limited to assessments of antibodies that can bind S protein expressed on target cells after transfection [15, 16, 17] or from an engineered stable cell line [18, 19]. None of these studies have investigated the ability of antibodies to bind and mediate ADCC using SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells. Given the current pandemic and emergence of novel variants, and awareness of potential future epidemics due to CoV infections, there is a need for detailed assessments of immune responses that may prevent, or promote, COVID‐19 with particular emphasis on understanding the role of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies in both non‐human primates and human clinical trials. Therefore, we developed assays for detection and measurement of antibody responses that can recognize and engage Fc‐Receptor‐bearing effector cells to eliminate SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells.

2. RESULTS

2.1. Development of assays to visualize and quantify antibody binding to, and effector functions against, SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells

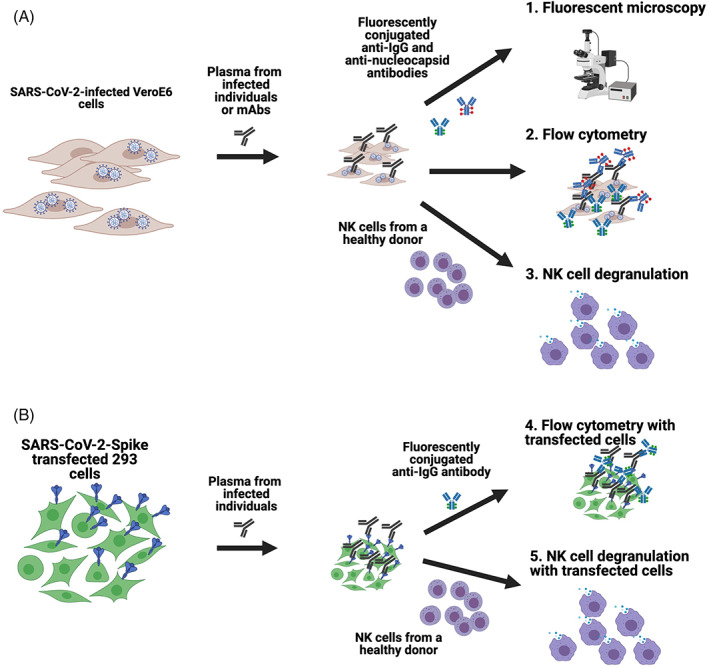

We first studied viral protein expression on the membrane of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected Vero E6 cells. We used this cell line because of its superior replication capacity compared to human epithelial cell lines, which require longer propagation time in vitro to infection, and its use in most live virus neutralization assays. We determined the expression of viral, and specifically Spike, proteins using both fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry‐based approaches. The same infected cells were used as target cells in an infected cell antibody binding assay and an infected cell antibody‐dependent NK cell degranulation assay, which we utilized to detect the presence of ADCC responses (Figure 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Schematics of the assays developed to assess antibody recognition of SARS‐CoV‐2 on the surface of infected and transfected cells. Vero E6 cells were infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 and then incubated with plasma from infected individuals or anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐specific monoclonal antibodies. Cells were then either stained with fluorescently conjugated anti‐IgG and anti‐Nucleocapsid antibodies to assess using fluorescent microscopy or flow cytometry, or incubated with NK cells from a healthy human donor to measure the capacity of antibodies to mediate NK cell degranulation (A). For transfected cell assays, 293 cells were transfected with SARS‐CoV‐2 spike plasmid, incubated with plasma from infected individuals and then stained with fluorescently conjugated anti‐IgG to assess using fluorescent microscopy or flow cytometry, or incubated with NK cells from a healthy human donor to measure the capacity of antibodies to mediate NK cell degranulation (B) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Moreover, we utilized an expression plasmid that encoded the SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike to transfect 293 cells which were then used as targets in an S‐protein‐expressing cell antibody binding assay and an S‐protein antibody‐dependent NK cell degranulation assay (Figure 1B). These transfection‐based assays have the advantage of suitability for BSL‐2 laboratories and are easier to scale for higher throughput. The results obtained with each type of target cells were compared to determine the extent to which each assay may provide different and relevant information for the field.

2.2. Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies can bind to SARS‐CoV‐2 on the surface of infected cells

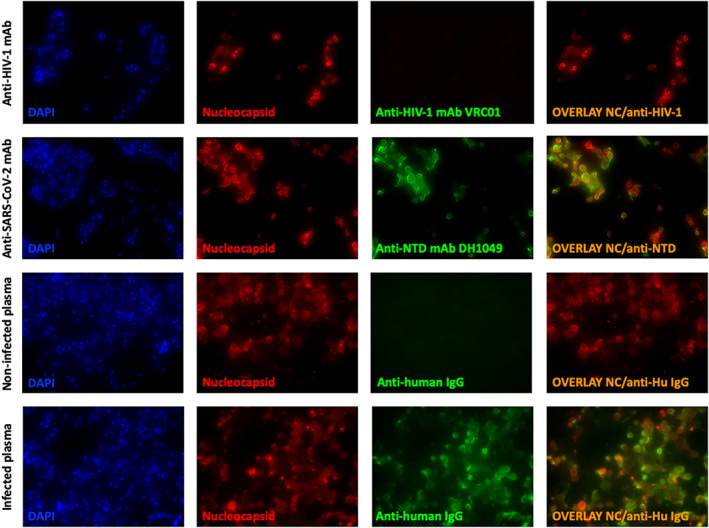

We began by using fluorescent microscopy to determine whether SARS‐CoV‐2 proteins were present on the plasma membrane of infected cells. We first confirmed that SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike was displayed on the surface of Vero E6 cells which had been infected with SARS‐CoV‐2 (isolate USA‐WA/2020). Surface Spike was stained with anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike N‐Terminal Domain (NTD) antibody, DH1049, isolated from a seroconvalescent individual and infected cells were identified by intracellular staining with a commercially available anti‐Nucleocapsid antibody (Figure 2, in red). We observed binding of DH1049 to the membrane of infected cells (Figure 2, in green) but we did not detect any binding of the anti‐HIV‐1 antibody, VRC01, which was used as negative control. To investigate if we could observe plasma antibody binding, we incubated infected cells with plasma (1:100) from a confirmed SARS‐CoV‐2 infected individual. We found that plasma antibodies from the infected individual bound to infected cells, while no binding was observed when plasma from an uninfected individual was used (Figure 2), or in parallel assays performed with mock‐infected targets (not shown).

FIGURE 2.

Fluorescent microscopy showing antibody binding SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells. Infected Vero E6 cells were stained intracellularly with an anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Nucleocapsid antibody (red), on the surface with controls (anti‐HIV‐1 monoclonal antibody, VRC01, or plasma from an uninfected individual) or SARS‐CoV‐2 specific antibody (anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 NTD mAb, DH1049, or sera from a SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individual) (green). Nucleated cells were identified using DAPI (blue) and an overlay of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Nucleocapsid and anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies bound to the surface of cells is shown (right column). Cells were visualized and pictures taken at 100× [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

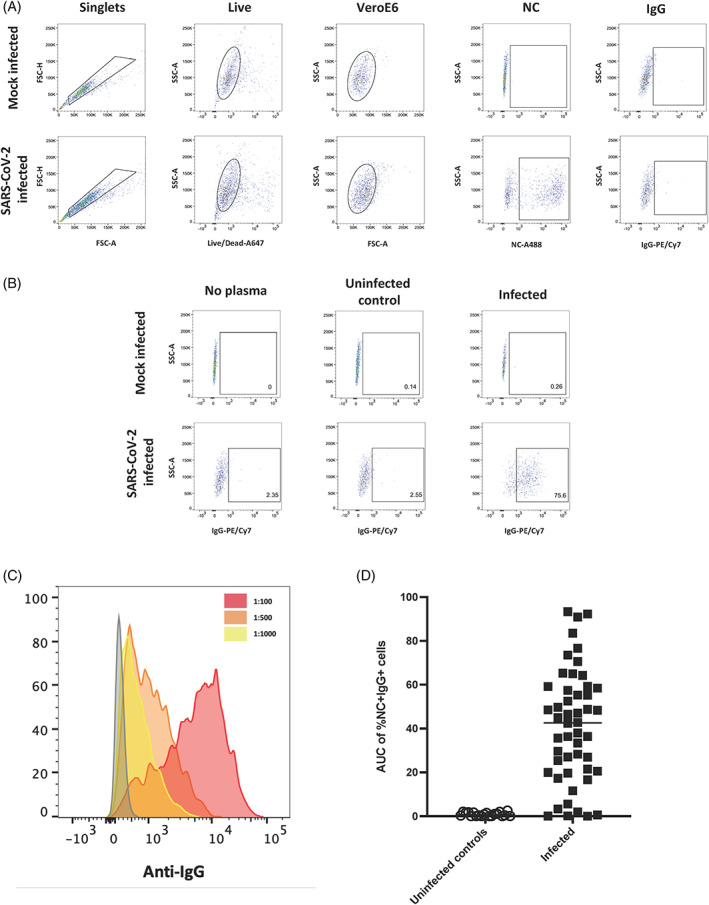

Having shown virus‐protein recognition by antibodies on the surface of infected cells, we developed a flow cytometry‐based infected cell antibody binding assay and tested plasma collected from 50 SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected and 20 non‐infected individuals for the presence of antibodies capable of binding SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected Vero E6 cells (Figure 3). The gating strategy used to detect human IgG binding to infected cells is shown in Figure 3A. We first identified singlets and viable cells. Infected cells were identified by intracellular SARS‐CoV‐2 nucleocapsid staining (NC+), then gated on anti‐IgG positive events (Figure 3A), while binding to mock infected cells was measured using the live cell gate. To ensure specificity, we used no plasma, plasma from an uninfected individual and plasma from a SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individual and incubated samples with either mock‐infected or SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (Figure 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Quantitating binding of antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells using flow cytometry. A gating strategy identifying singlets, live cells and Vero E6 cells was used to detect cells followed by gating for the presence of Nucleocapsid and IgG on mock infected and SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (A). No plasma, plasma from an uninfected individual and plasma from an infected individual were used to assess specificity of antibody binding to mock infected and SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (B). A histogram of events acquired using plasma from an infected individual which was diluted to three different dilutions (1:100, red; 1:500, orange and 1:1000, yellow) (C). The AUC of %NC + IgG+ cells at three dilutions (1:100, 1:500 and 1:1000) was calculated for uninfected controls (n = 20) and SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals (n = 50) (D) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Plasma samples from uninfected and infected individuals were then tested at three different dilutions (1:100, 1:500, and 1:1000) to determine the presence of plasma antibodies capable of binding to the infected cells. After determining the level of IgG binding to mock‐infected cells and subtracting this background signal from the signal observed with infected cells, we observed dose‐dependent binding of antibodies based on the plasma dilution (Figure 3C). We then calculated the area under the dilution curve (AUC) for IgG binding to infected cells (Figure 3D). A mean AUC value of 42.4 in the infected samples (range: 0.01–92.3) was observed, whereas samples from uninfected subjects (n = 20) had a median AUC of 0.6 (range: 0–2.1). Using the mean AUC + two standard deviations (SD) of the uninfected subjects, we calculated a positive cut‐off value for the assay of AUC > 2.4. Next, we investigated the precision and reproducibility of the assay by repeating a subset of the plasma samples (n = 12 total: n = 10 above the cut‐off and n = 2 below the cut‐off) three times and found no differences between the assays (Figure S1A, Kruskal‐Wallis p = 0.94) with all samples consistently above or below the calculated cut‐off value and an average coefficient of variation (CV) of 12.1% for the 10 samples that were above the cut‐off (range: 2.6%–16.1%).

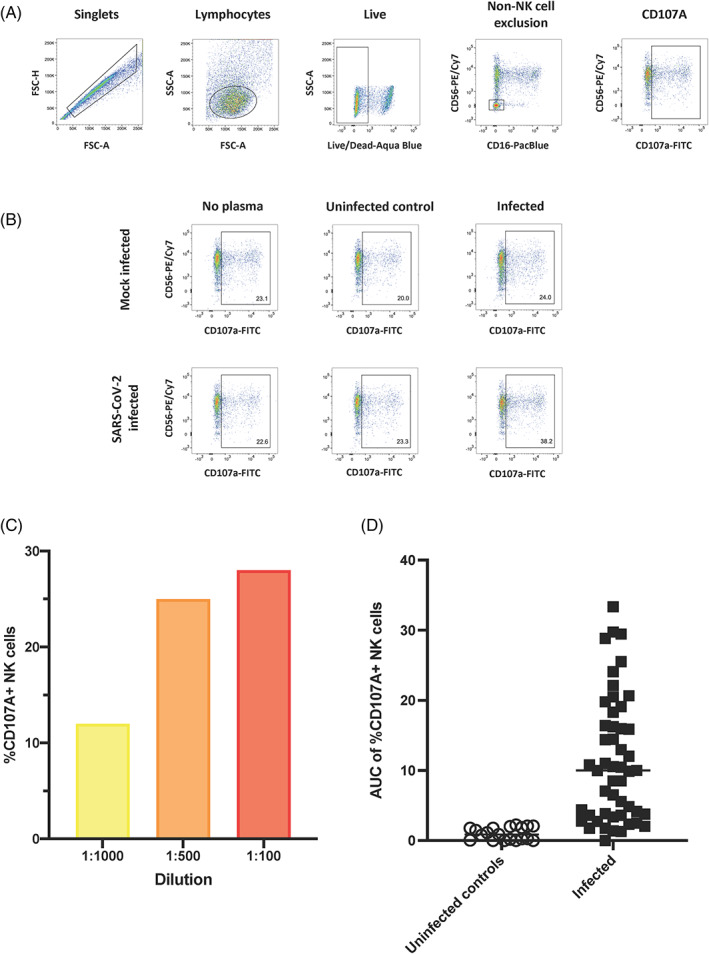

2.3. Anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 antibodies can mediate NK cell degranulation in the presence of infected cells

After we determined that SARS‐CoV‐2‐specific antibodies could bind to the surface of infected cells, we tested whether these antibodies were capable of stimulating NK cell degranulation in the presence of infected cells (Figure 4). To do this, we used a flow cytometry‐based assay which identified degranulating NK cells by the cell surface expression of CD107a on the cell surface in the presence of antibody and antigen [20]. NK cells used in these assays were purified from PBMC of a healthy human donor. The gating strategy used to identify live degranulating NK cells is shown in Figure 4A. Again, to ensure specificity, we used no plasma, plasma from an uninfected individual and plasma from a SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individual, and incubated samples with NK cells and either mock‐infected or SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (Figure 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Assessing the ability of antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells to mediate NK cell degranulation. A gating strategy identifying singlets, lymphocytes and live cells was used to detect cells followed by excluding non‐NK cell events and gating for CD107a + NK cells on mock infected and SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (A). No plasma, plasma from an uninfected individual and plasma from an infected individual were used to assess specificity of NK cell degranulation in the presence or absence of plasma and mock infected or SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (B). The %CD107a + NK cells detected using plasma from a single infected individual which was diluted to three different dilutions (1:100, red; 1:500, orange and 1:1000, yellow) (C). The AUC of %CD107a + NK cells cells at three dilutions (1:100, 1:500 and 1:1000) was calculated for uninfected controls (n = 20) and SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals (n = 50) (D) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We then used an NK cell degranulation assay to predict cell lysis because it is a strong predictor and prerequisite for ADCC [21]. We determined the extent of NK cell degranulation in the presence of infected cells and plasma antibodies from uninfected and infected individuals at three different dilutions (1:100, 1:500, and 1:1000) and observed dose‐dependent NK cell responses (Figure 4C). After accounting for NK cell degranulation in the presence of mock‐infected cells (background subtraction), we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) of CD107a + NK cells (Figure 4D). A median AUC value of 10.0 was observed in the infected samples (range: 0–33.4), whereas samples from the uninfected subjects (n = 20) had a median AUC of 0.9 (range: 0–2.2). Using the mean AUC + 2SD of the uninfected subjects, we calculated a positive cut‐off value for the assay of AUC > 2.4. We then investigated the precision and reproducibility of this assay with the same subset of the plasma (n = 12 total: n = 10 above the calculated cut‐off and n = 2 below the calculated cut‐off) as above and again found no differences between repeats (Figure S1, Kruskal‐Wallis p = 0.99) and an average %CV of 11.4% for the 10 samples which were above the cut‐off (range: 3.5%–25.9%).

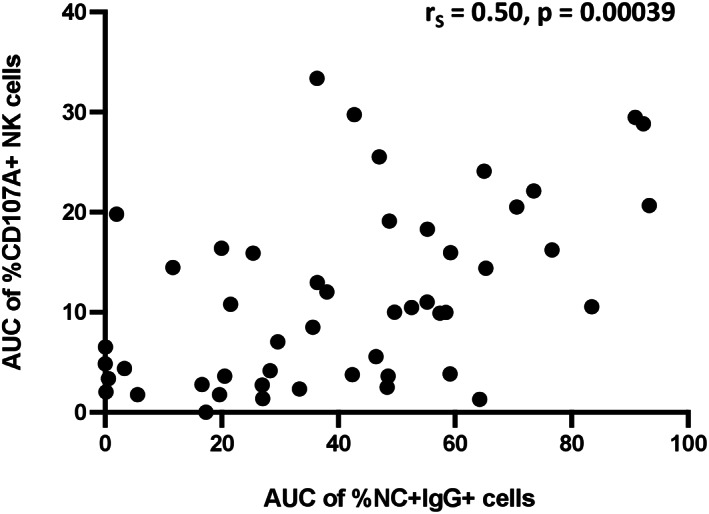

Lastly, we assessed the relationship between binding and degranulation. We found NK cell degranulation only moderately correlated with IgG binding to infected cells (Figure 5; r S = 0.50, p = 0.00039), suggesting that there is an incomplete overlap between these two antibody functions.

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation and antibody binding to SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells. AUC of %CD107a + NK cells and %NC + IgG+ cells was plotted and a spearman test was used to determine the strength of relationship

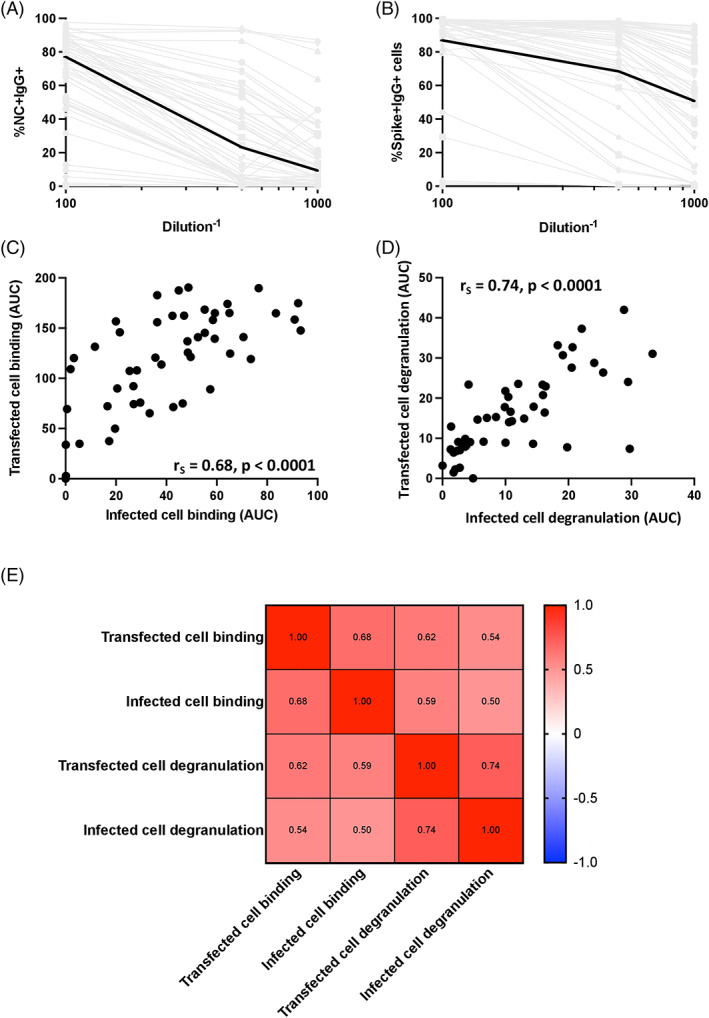

2.4. Transfected cell assays do not fully correlate with infected cell assays using plasma from infected individuals

Having established that antibodies from SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals were able to bind to infected cells and mediate NK cell degranulation, we proceeded to investigate the extent to which responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike‐transfected cells could be a surrogate to evaluate responses to infected cells. If this is possible, we could reduce our needs to evaluate responses to infected cells that require a BSL‐3 environment that is not widely accessible by investigators in the field. To do this, we developed SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike‐transfected cell binding and degranulation assays (Figure 1B). SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike‐transfected cells were identified using an anti‐flag antibody which bound to a flag tag fused to the c‐terminus of the Spike protein. When comparing binding of antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells (Figure 6A, %NC + IgG+ cells) with antibody binding to Spike‐transfected cells (Figure 6B, %Spike + IgG+ cells) at three dilutions (1:100, 1:500 and 1:1000), we found substantially higher levels of binding to transfected cells (median %Spike + IgG+ cells of 87, 69 and 51 for transfected cell binding compared to median %NC + IgG+ cells of 77, 23 and nine for infected cell binding). These data suggest that the transfected cell assay may be more sensitive in detection of Spike‐specific antibody responses. While the magnitude of responses detected was higher in the transfected cell assay, there was still a moderate positive relationship between the two assays, with r s = 0.68 (p < 0.0001, Figure 6C). In comparison, the magnitude of antibody‐dependent NK cell degranulation detected in the transfected cell and infected cell degranulation assays resulted in a moderate positive relationship (r s = 0.74, p < 0.0001) between the two assays (Figure 6D). Lastly, to investigate the extent to which each of the four assays correlated with the other assays, we did a pairwise Spearman correlation (Figure 6E). We found that the highest correlation between two assays was the moderate positive relationship observed between the transfected cell and infected cell antibody‐dependent NK cell degranulation assays (r s = 0.74). All other Spearman rho's fell between 0.5 and 0.7, suggesting that the assays may be interrelated, but each also detects unique aspects of antibody responses targeting antigen‐expressing cells.

FIGURE 6.

Relationship between transfected cell and infected cell assays. Binding curves for plasma of the 50 SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals against infected (A) and transfected (B) cells were generated. Infected cell binding was measured by %NC + IgG+ cells and transfected cell binding was measured by %spike + IgG+ cells. Spike+ cells were identified using an anti‐flag antibody which bound to a flag tag fused to the c‐terminus of the spike protein. Median binding levels are shown by the black lines and gray lines indicated binding responses for individual plasma samples. The relationship between AUCs measured by transfected cell binding and infected cell binding (C) and AUCs of NK cell degranulation in the presence of transfected and infected cells (D) were calculated using a spearman test. The relationship between all four assays was then determined using a spearman test (D) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

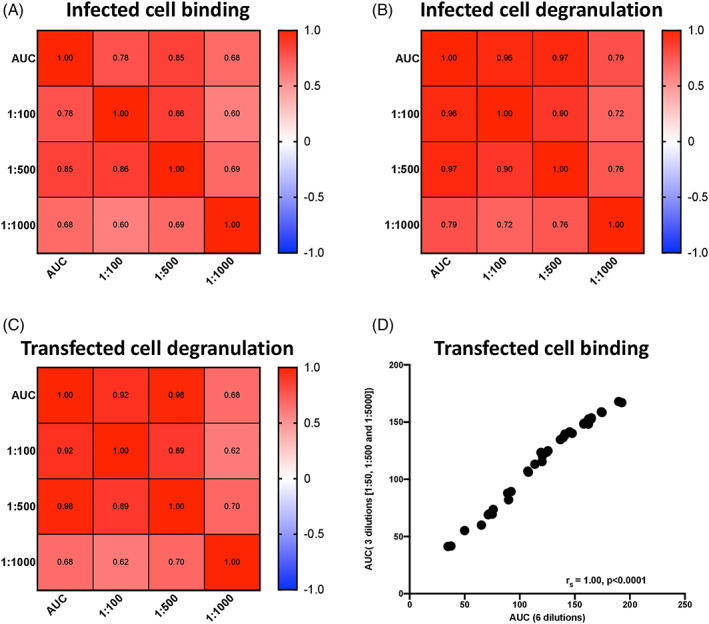

2.5. Plasma dilutions can be reduced to increase the throughput of infected and transfected cell assays

Finally, in an effort to make each assay higher throughput and more economical for the large number of samples involved in clinical studies and trials, we investigated the relationship between the AUC of three dilutions and each single dilution (for the infected cell and the transfected cell degranulation assays) and the AUC of six dilutions and the AUC of three dilutions for the transfected cell binding assay. For the infected cell antibody binding assay, the 1:500 dilution strongly correlated with the AUC (r s 0.85; Figure 7A), allowing the use of a single dilution for evaluating binding to infected cells. This was true for the infected and transfected cell degranulation assays as well, where we observed strong correlations between the 1:500 dilution and AUC (r s = 0.97 and 0.98, respectively) (Figure 7B,C) indicating assessing antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation at 1:500 dilution is sufficient to capture responses due to antibodies in sera. Lastly, we investigated the correlation of the AUC of six dilutions (1:50, 1:100, 1:500, 1:1000, 1:5000 and 1:10,000) and the AUC of three dilutions (1:50, 1:500 and 1:5000) for transfected cell binding (Figure 7D). We found a strong correlation (r s = 1.00, p < 0.0001), signifying that these three dilutions accurately represented the full binding curves and could be used in immunogenicity assessment assays.

FIGURE 7.

Correlations between single or reduced dilutions and AUC for infected cell binding and antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation assays. The relationship between the AUC of three dilutions of antibody and single dilutions in infected cell binding (A), infected cell degranulation (B) and transfected cell degranulation (C) were determined using a spearman test. The relationship between the AUC of transfected cell binding at three dilutions (50, 500 and 5000) and six dilutions (50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000 and 10,000) was plotted and determined using a spearman test (D) [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3. DISCUSSION

The role of antibody responses targeting SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells is understudied and, consequently, undetermined. To provide tools to study these responses, we developed four specific, reproducible assays, each adaptable to circulating SARS‐CoV‐2 variants, to investigate these responses: two using SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells and two using Spike‐transfected cells. We show, for the first time, antibody binding to, and antibody mediated NK cell degranulation in the presence of, SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells.

We observed, similar to other studies, differences between antibody binding and antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation, suggesting there are different requirements for each function and that each assay will play an important role in deciphering the role of antibody responses against infected cells [19]. While antibodies need to bind to cells to mediate NK cell degranulation, this may not be measured fully by the binding assays, which are cross‐sectional and capture only binding events that are present during the limited incubation period of antibodies with infected or Spike‐transfected cells. In comparison, the antibody‐mediated NK cell degranulation assays are cumulative and measure events that occur during the entire period of incubation. In addition, differences between the assays may be explained by glycosylation of the antibody Fc or the angle of antibody binding to antigens on infected/transfected cells, which may prohibit Fc binding to the Fc‐gamma‐receptor IIIA (FcyRIIIA) on NK cells and prevent NK cell degranulation. However, that does not preclude the possibility that binding antibodies that do not mediate NK cell degranulation are facilitating other Fc effector functions such as complement activation or phagocytosis through other immune cells. In addition, the differences observed may be due the binding assays measuring total IgG binding to infected/transfected cells, while individual IgG subclasses are known to contribute differently to antibody effector functions [22, 23].

We observed quantitative differences in antibody responses to virus‐infected and Spike‐transfected cells, likely due to the levels of expression of proteins on the cell surface and possibly also due to the presence of antibodies targeting proteins other than the Spike, such as the Nucleocapsid, on the surface of infected cells [24]. The role of antibodies targeting proteins other than Spike is undetermined and requires further study. Conversely, anti‐Spike antibodies are of high interest and have been the focus of both passive immunization [25] and vaccination strategies [26]. The focus to date has been on virus or viral protein binding and neutralizing antibodies which have correlated with prevention of transmission and protection from severe disease [27, 28]. However, it is possible these correlates could be, in part, acting as a proxy for Fc functionality. Indeed, the recent correlates' analysis of the Moderna SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine, mRNA‐1273, phase III trial results by Gibert et al. revealed 90% vaccine efficacy by day 29 but measurable neutralizing antibodies in only 18% of vaccine recipients, strongly suggesting other antibody functions play an important role in protection [27]. In addition, another study found that antibody effector functions contributed to monoclonal antibody protection from SARS‐CoV‐2 protection in hamster and mouse models [29].

We have already successfully adapted these assays to evaluated vaccine‐induced ADCC responses in non‐human primates. Interestingly, we found that Spike‐transfected cell antibody binding and NK cell degranulation also correlated with reduced viral RNA in a pre‐clinical study that evaluated the effect of adjuvants on a vaccine regimen tested in Rhesus macaques (RM) [30]. These responses were also able to distinguish between groups of RMs that received different adjuvants. Consequently, assays that specifically measure effector functions of antibodies targeting this protein are important and of high interest in the evaluation of responses induced in both pre‐ and clinical studies.

Lastly, while we initially developed each assay with multiple dilutions in an effort to capture the full relationship between antibody doses and assay outcome, we explored the relationship between fewer antibody dilutions and the full dilution series for each assay to reduce assay costs and improve assay efficiency. We were able to reduce the number of wells to allow for high‐throughput assays for use in assessment of antibodies elicited by infection and vaccination in large studies.

In conclusion, we have developed a suite of four assays that can be used individually or as a set to assess different aspects of antibody responses elicited through vaccination or infection and targeting SARS‐CoV‐2 antigens on the surface of infected or transfected cells. These assays are precise, reproducible and have been developed to be high throughput, allowing for their use in immunomonitoring of large clinical studies.

4. METHODS

4.1. Plasma samples and monoclonal antibodies

Plasma from 15 SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals in the Epidemiological Study of Serial Transmission Cohort and 35 SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals from the HVTN 405/HPTN 1901 cohort were used to assess immune responses. Samples came from asymptomatic (n = 6), symptomatic (n = 37) and hospitalized (n = 7) individuals; and the median time from infection to sample collection for the 50 individuals was 42 days (range: 3–73 days). Plasma from five SARS‐CoV‐2 negative individuals from the Epidemiological Study of Serial Transmission Cohort and plasma from 15 individuals acquired from the BioIVT Inc. were used as negative control samples. The anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike NTD monoclonal antibody, DH1049, was kindly provided by Dr. Barton Haynes, DHVI, Duke University [31].

4.2. Cell lines

Vero E6 cells were cultured in MEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 μg/ml Penicillin and Streptomycin solution at 37°C and 5% CO2. 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% heat‐inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 μg/ml Penicillin and Streptomycin solution at 37°C and 5% CO2. 293F cells were cultured in Freestyle 293 expression media (Thermofisher) at 37°C and 8% CO2.

4.3. Microscopy of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells using monoclonal antibodies

The day before infection, 1 × 104 Vero E6 cells per well were seeded in an eight well chamber slide (Nunc Labtek chamber slides, Thermoscientific). On the day of infection, SARS‐CoV‐2, isolate USA‐WA/2020 (BEI resources, cat no. NR‐52281) was added to cells at an MOI of 0.01. The infection was carried out for 48 h. Cell layers were washed and incubated with 8 μg/ml A568‐conjugated monoclonal antibody for 30 min at room temperature (RT), washed and fixed in 10% neutral‐buffered formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature (Duke GHRB SOP 38, attachment 21). After two washes with Wash Buffer (1%FBS‐PBS; WB), cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton for 5 min at RT. Blocking buffer was added and the cells were incubated at 4°C for 4 h. After washing, 10 μg/ml anti‐SARS‐COV‐2 nucleocapsid antibody (40143‐MM08, Sino Biological), conjugated with A488 using an Alexa fluor antibody labelling kit (Invitrogen) was added and incubated at 4°C overnight with rocking. Cells were then washed and Fluorshield DAPI reagent (Sigma) added before the cover slip was mounted on the slide. Cells were visualized using a Keyence BZ‐X710 fluorescent microscope and images analyzed using BZ‐X Analyzer software (v1.3.11).

4.4. Microscopy of SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected cells using polyclonal antibodies in plasma

Infected cells were prepared as described above. On the day of assay, Cell layers were washed and incubated with plasma from infected individuals diluted at 1:100 for 30 min at room temperature (RT), washed and fixed in 10% neutral‐buffered formaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature (Duke GHRB SOP 38, attachment 21). After two washes with Wash Buffer (1%FBS‐PBS; WB), cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton for 5 min at RT. Blocking buffer was added and the cells were incubated at 4°C for 4 h. After washing, 10 μg/ml anti‐SARS‐COV‐2 nucleocapsid antibody (40143‐MM08, Sino Biological), conjugated with A568 using an Alexa fluor antibody labelling kit (Invitrogen), was added and incubated at 4°C overnight with rocking. After washing, A488‐conjugated anti‐Human IgG Fc antibody (Clone: HP6017, Biolegend) was added and incubated for 30 min at 4°C on a rocking platform. Cells were then washed and Fluorshield DAPI reagent (Sigma) added before the cover slip was mounted on the slide. Cells were visualized using a Keyence BZ‐X710 fluorescent microscope and images analyzed using BZ‐X Analyzer software (v1.3.11).

4.5. Infected‐cell antibody binding assay

The binding of anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 monoclonal antibodies and plasma from SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected individuals to cells was measured as a modification of our previously described procedures [32, 33]. Briefly, infected Vero E6 cells were incubated with TrypLE Select (Gibco) for 15 min at 37°C to detach cells, and washed with PBS. The anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 NTD antibody, DH1049 (kindly provided by Dr. Haynes), and anti‐HIV‐1 antibody, VRC01 (negative control), were added to infected cells at 8 μg/ml; plasma from infected individuals was added at 1:100, 1:500, and 1:1000 dilutions. Approximately 2 × 105 infected cells were incubated with either source of antibodies for 30 min at room temperature, washed and then incubated with vital dye (Live/Dead Far Red Dead Cell Stain, Invitrogen) for 15 min at room temperature to exclude nonviable cells from subsequent analysis. Cells were then washed with Wash Buffer (1%FBS‐PBS; WB), pelleted by centrifugation and incubated with 1 ml of 4% Methanol‐free Formaldehyde (Duke GHRB SOP 38; Attachment 17) for 30 min at Room Temperature. Cells were then washed twice with Wash Buffer, permeabilized with CytoFix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences) and stained with A568‐conjugated anti‐SARS‐COV‐2 nucleocapsid antibody (40143‐MM08, Sino Biological) and PE/Cy7‐conjugated secondary anti‐Human IgG Fc antibody (Clone: HP6017, Biolegend) for 30 min at room temperature. Cells were washed and resuspended in 250 μl PBS–1% paraformaldehyde. Samples were acquired within 24 h using a BD Fortessa cytometer and a High Throughput Sampler (HTS, BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo 10 software (BD Biosciences). Gates were set to include singlet, live, nucleocapsid+ (NC+) and IgG+ events. Binding to mock infected cells was measured using the live cell gate as there were no NC+ events. All final data represent specific binding, determined by subtraction of non‐specific binding observed in assays performed with mock‐infected cells.

4.6. Spike protein‐expressing cell antibody binding assay

The Spike‐transfected cell antibody binding assay was performed based on our previously described methods [32, 33], modified to use target cells derived by transfection with plasmids designed to express the SARS‐CoV‐2 D614 Spike protein with a c‐terminus flag tag (kindly provided by Dr. Farzan, Addgene plasmid no. 156420 [34]). Cells not transfected with any plasmid (mock transfected) were used as a negative control condition. After resuspension, washing and counting, 1 × 105 Spike‐transfected target cells were dispensed into 96‐well V‐bottom plates and incubated with six serial dilutions of human plasma from infected participants starting at 1:50 dilution. Mock transfected cells were used as a negative control. After 30 min incubation at 37°C, cells were washed twice with 250 μl/well of PBS, stained with vital dye (Live/Dead Far Red Dead Cell Stain, Invitrogen) to exclude nonviable cells from subsequent analysis, washed with Wash Buffer (1%FBS‐PBS; WB), permeabilized with CytoFix/CytoPerm (BD Biosciences), and stained with 1.25 μg/ml anti‐human IgG Fc‐PE/Cy7 (Clone HP6017; Biolegend) and 5 μg/ml anti‐flag‐FITC (clone M2; Sigma Aldrich) in the dark for 20 min at room temperature. After three washes with Perm Wash (BD Biosciences), the cells were resuspended in 125 μl PBS‐1% paraformaldehyde. Samples were acquired within 24 h using a BD Fortessa cytometer and a High Throughput Sampler (HTS, BD Biosciences). Data analysis was performed using FlowJo 10 software (BD Biosciences). A minimum of 50,000 total events were acquired for each analysis. Gates were set to include singlet, live, flag+ (Spike+) and IgG+ events. Binding to mock infected cells was measured using the live cell gate as there were no flag+ events. All final data represent specific binding, determined by subtraction of non‐specific binding observed in assays performed with mock‐transfected cells.

4.7. Antibody‐dependent NK cell degranulation assays (infected and spike‐transfected)

Cell‐surface expression of CD107a was used as a marker for NK cell degranulation, a prerequisite process for, and strong correlate of, ADCC [21], performed by adapting a previously described procedure [20]. Briefly, target cells were either Vero E6 cells after a 2 day‐infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 USA‐WA1/2020 or 293T cells 2‐days post transfection with a SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein (D614) expression plasmid.

Natural killer cells were purified by negative selection (Miltenyi Biotech) from peripheral blood mononuclear cells obtained by leukapheresis from a healthy, SARS‐CoV‐2‐seronegative individual (Fc‐gamma‐receptor IIIA [FcyRIIIA]158 V/F heterozygous) and previously assessed for FcyRIIIA genotype and frequency of NK cells were used as a source of effector cells. NK cells were incubated with target cells at a 1:1 ratio in the presence of diluted plasma or monoclonal antibodies, Brefeldin A (GolgiPlug, 1 μl/ml, BD Biosciences), monensin (GolgiStop, 4 μl/6 ml, BD Biosciences), and anti‐CD107a‐FITC (BD Biosciences, clone H4A3) in 96‐well flat bottom plates for 6 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. NK cells were then recovered and stained for viability prior to staining with CD56‐PECy7 (BD Biosciences, clone NCAM16.2), CD16‐PacBlue (BD Biosciences, clone 3G8), and CD69‐BV785 (Biolegend, Clone FN50). The NK cells from the infected cell assay were incubated with 0.2 ml of 4% Methanol‐free Formaldehyde (Duke GHRB SOP 38; Attachment 17) for 30 min at Room Temperature. Cells were then resuspended in 115 μl PBS–1% paraformaldehyde. Flow cytometry data analysis was performed using FlowJo software (v10.8.0). Data is reported as the % of CD107a + live NK cells (gates included singlets, lymphocytes, aqua blue−, CD56+ and/or CD16+, CD107a+). All final data represent specific activity, determined by subtraction of non‐specific activity observed in assays performed with mock‐infected cells and in the absence of antibodies.

4.8. Statistical analysis

Area under the curve (AUC) for each assay was calculated from dilution curves using a nonlinear trapezoidal method and dilutions of 1:100, 1:500 and 1:1000. Similarly, the AUC for the Spike‐expressing cell antibody binding assay was calculated from a six‐dilution curve (50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000 and 10,000) or a three‐dilution curve (50, 500 and 5000) using a non‐linear trapezoidal method. Correlations between responses from different assays were studied using a Spearman correlation. Differences in responses between two assays were studied using Wilcoxon tests. p values < 0.05 were considered significant.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dieter Mielke: Conceptualization (equal); investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Sherry Stanfield‐Oakley: Investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Shalini Jha: Formal analysis (equal); visualization (supporting); writing – original draft (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Taylor Keyes: Investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Adam Zalaquett: Investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Brooke Dunn: Investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Nicole Rodgers: Investigation (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Thomas Oguin: Resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Greg D. Sempowski: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Raquel A. Binder: Resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Gregory C. Gray: Resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Shelly Karuna: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Lawrence Corey: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal). John Hural: Resources (equal). Georgia D. Tomaras: Funding acquisition (equal); resources (equal). Justin Pollara: Conceptualization (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Guido Ferrari: Conceptualization (equal); funding acquisition (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

GDS has a patent application pending for the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 mAB, DH1049. All other authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This work was supported by the non‐human primate core humoral immunology laboratory for AIDS vaccine Option 28 – Additional effort for COVID‐19 (HHSN272201800004C) and the HVTN Laboratory Center: HVTN405 (3 UM1 AI068618‐14S1). BSL‐3 high containment work was performed in the Duke Regional Biocontainment Laboratory, which received partial support for construction from the NIH/NIAID (AI058607; GDS). DH1049 antibody was isolated with support from a cooperative agreement with DOD/DARPA (HR0011‐17‐2‐0069; GDS).

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

MIFlowCyt MIFlowCyt Item Checklist.

Figure S1: Reproducibility and precision of infected cell binding (A) and degranulation (B) and transfected cell binding (C) and degranulation (D) assays. Each assay was repeated three times, and the dilutions with standard deviations (left) and AUCs (right) were plotted. The 12 samples were chosen to represent a range of responses including high (green), medium (orange) and low (red).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the participants and clinical research staff of the ESST and HVTN 405/HPTN 1901 studies for providing samples, Drs Dapeng Li and Barton Haynes for providing the anti‐SARS‐CoV‐2 monoclonal antibody DH1049, and Dr Michael Farzan for providing the plasmid, pCAGGS‐SARS‐CoV‐2 Spike D614 (c‐flag).

Mielke D, Stanfield‐Oakley S, Jha S, Keyes T, Zalaquett A, Dunn B, et al. Development of flow cytometry‐based assays to assess the ability of antibodies to bind to SARS‐CoV‐2‐infected and spike‐transfected cells and mediate NK cell degranulation. Cytometry. 2022;101:483–496. 10.1002/cyto.a.24552

Funding information National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant/Award Numbers: 3 UM1 AI068618‐14S1, AI058607, HHSN272201800004C; U.S. Department of Defense, Grant/Award Number: HR0011‐17‐2‐0069

Contributor Information

Dieter Mielke, Email: dieter.mielke@duke.edu.

Guido Ferrari, Email: gflmp@duke.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kuiken T, Fouchier RAM, Schutten M, Rimmelzwaan GF, van Amerongen G, van Riel D, et al. Newly discovered coronavirus as the primary cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet (London, England). 2003;362:263–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13967-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cui J, Li F, Shi Z‐L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2019;17:181–92. 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Franks TJ, Chong PY, Chui P, Galvin JR, Lourens RM, Reid AH, et al. Lung pathology of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS): a study of 8 autopsy cases from Singapore. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:743–8. 10.1016/s0046-8177(03)00367-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nicholls JM, Poon LLM, Lee KC, Ng WF, Lai ST, Leung CY, et al. Lung pathology of fatal severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet (London, England). 2003;361:1773–8. 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13413-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1282:1–23. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2438-7_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lontok E, Corse E, Machamer CE. Intracellular targeting signals contribute to localization of coronavirus spike proteins near the virus assembly site. J Virol. 2004;78:5913–22. 10.1128/JVI.78.11.5913-5922.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhou P, Yang X‐L, Wang X‐G, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579:270–3. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–80. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tian S, Hu W, Niu L, Liu H, Xu H, Xiao S‐Y. Pulmonary pathology of early‐phase 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID‐19) pneumonia in two patients with lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:700–4. 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Atyeo C, Fischinger S, Zohar T, Slein MD, Burke J, Loos C, et al. Distinct early serological signatures track with SARS‐CoV‐2 survival. Immunity. 2020;53:524–32.e4. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.07.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bartsch YC, Fischinger S, Siddiqui SM, Chen Z, Yu J, Gebre M, et al. Discrete SARS‐CoV‐2 antibody titers track with functional humoral stability. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1018. 10.1038/s41467-021-21336-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gorman MJ, Patel N, Guebre‐Xabier M, Zhu AL, Atyeo C, Pullen KM, et al. Fab and fc contribute to maximal protection against SARS‐CoV‐2 following NVX‐CoV2373 subunit vaccine with matrix‐M vaccination. Cell Reports Med. 2021;2:100405. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winkler ES, Gilchuk P, Yu J, Bailey AL, Chen RE, Chong Z, et al. Human neutralizing antibodies against SARS‐CoV‐2 require intact fc effector functions for optimal therapeutic protection. Cell. 2021;184:1804–20.e16. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Holmes MJ, Callow KA, Childs RA, Tyrrell DA. Antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity against coronavirus 229E‐infected cells. Br J Exp Pathol. 1986;67:581–6. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3017399 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Keeton R, Richardson SI, Moyo‐Gwete T, Hermanus T, Tincho MB, Benede N, et al. Prior infection with SARS‐CoV‐2 boosts and broadens Ad26.COV2.S immunogenicity in a variant‐dependent manner. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(11):1611–1619. 10.1016/j.chom.2021.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tso FY, Lidenge SJ, Poppe LK, Peña PB, Privatt SR, Bennett SJ, et al. Presence of antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) against SARS‐CoV‐2 in COVID‐19 plasma. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0247640. 10.1371/journal.pone.0247640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yu Y, Wang M, Zhang X, Li S, Lu Q, Zeng H, et al. Antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity response to SARS‐CoV‐2 in COVID‐19 patients. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(346). 10.1038/s41392-021-00759-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beaudoin‐Bussières G, Richard J, Prévost J, Goyette G, Finzi A. A new flow cytometry assay to measure antibody dependent cellular cytotoxicity against SARS‐CoV‐2 spike expressing cells. STAR Protoc. 2021;2(4):100851. 10.1016/j.xpro.2021.100851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen X, Rostad CA, Anderson LJ, Sun HY, Lapp SA, Stephens K, et al. The development and kinetics of functional antibody‐dependent cell‐mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) to SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein. Virology. 2021;559:1–9. 10.1016/j.virol.2021.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nelson CS, Huffman T, Jenks JA, Cisneros de la Rosa E, Xie G, Vandergrift N, et al. HCMV glycoprotein B subunit vaccine efficacy mediated by nonneutralizing antibody effector functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:6267–72. 10.1073/pnas.1800177115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alter G, Malenfant JM, Altfeld M. CD107a as a functional marker for the identification of natural killer cell activity. J Immunol Methods. 2004;294:15–22. 10.1016/j.jim.2004.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Alter G, Ottenhoff THM, Joosten SA. Antibody glycosylation in inflammation, disease and vaccination. Semin Immunol. 2018;39:102–10. 10.1016/j.smim.2018.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM, Alter G. Beyond binding: antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:46–61. 10.1038/nri.2017.106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brochot E, Demey B, Touzé A, Belouzard S, Dubuisson J, Schmit J‐L, et al. Anti‐spike, anti‐nucleocapsid and neutralizing antibodies in SARS‐CoV‐2 inpatients and asymptomatic individuals. Front Microbiol. 2020;11. 10.3389/fmicb.2020.584251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klasse P, Moore JP. Antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2 and their potential for therapeutic passive immunization. eLife. 2020;9:e57877. 10.7554/eLife.57877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wang Z, Schmidt F, Weisblum Y, Muecksch F, Barnes CO, Finkin S, et al. mRNA vaccine‐elicited antibodies to SARS‐CoV‐2 and circulating variants. Nature. 2021;592:616–22. 10.1038/s41586-021-03324-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gilbert PB, Montefiori DC, McDermott AB, Fong Y, Benkeser D, Deng W, et al. Immune correlates analysis of the mRNA‐1273 COVID‐19 vaccine efficacy clinical trial. Science. 2021;375(6576):43–50. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34812653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–11. 10.1038/s41591-021-01377-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schäfer A, Muecksch F, Lorenzi JCC, Leist SR, Cipolla M, Bournazos S, et al. Antibody potency, effector function, and combinations in protection and therapy for SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in vivo. J Exp Med. 2021;218(3):e20201993. 10.1084/jem.20201993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pino M, Abid T, Pereira Ribeiro S, Edara VV, Floyd K, Smith JC, et al. A yeast‐expressed RBD‐based SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccine formulated with 3M‐052‐alum adjuvant promotes protective efficacy in non‐human primates. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(61). 10.1126/sciimmunol.abh3634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li D, Edwards RJ, Manne K, Martinez DR, Schäfer A, Alam SM, et al. In vitro and in vivo functions of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection‐enhancing and neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2021;184:4203–19.e32. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bradley T, Pollara J, Santra S, Vandergrift N, Pittala S, Bailey‐Kellogg C, et al. Pentavalent HIV‐1 vaccine protects against simian‐human immunodeficiency virus challenge. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15711. 10.1038/ncomms15711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ferrari G, Pollara J, Kozink D, Harms T, Drinker M, Freel S, et al. An HIV‐1 gp120 envelope human monoclonal antibody that recognizes a C1 conformational epitope mediates potent antibody‐dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) activity and defines a common ADCC epitope in human HIV‐1 serum. J Virol. 2011;85:7029–36. 10.1128/JVI.00171-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, Ojha A, Peng H, Quinlan BD, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 spike‐protein D614G mutation increases virion spike density and infectivity. Nat Commun. 2020;11:6013. 10.1038/s41467-020-19808-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Supporting Information

MIFlowCyt MIFlowCyt Item Checklist.

Figure S1: Reproducibility and precision of infected cell binding (A) and degranulation (B) and transfected cell binding (C) and degranulation (D) assays. Each assay was repeated three times, and the dilutions with standard deviations (left) and AUCs (right) were plotted. The 12 samples were chosen to represent a range of responses including high (green), medium (orange) and low (red).