Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review assessed the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic and associated restrictions on body image, disordered eating (DE), and eating disorder outcomes.

Methods

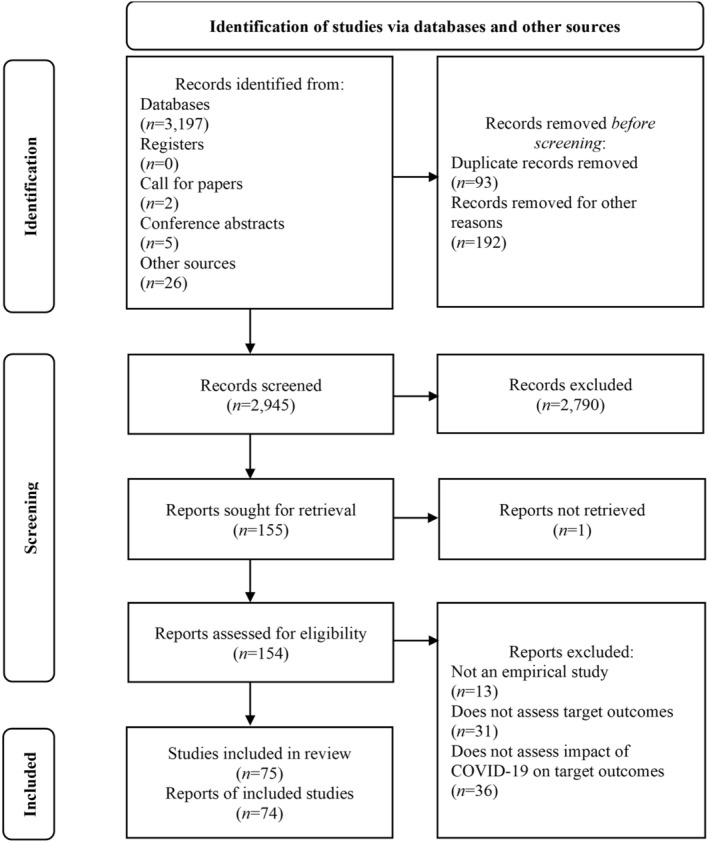

After registration on PROSPERO, a search was conducted for papers published between December 1, 2019 and August 1, 2021, using the databases PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL Plus, AMED, MEDLINE, ERIC, EMBASE, Wiley, and ProQuest (dissertations and theses).

Results

Data from 75 qualitative, quantitative, and mixed‐methods studies were synthesized using a convergent integrated approach and presented narratively within four themes: (1) disruptions due to the COVID‐19 pandemic; (2) variability in the improvement or exacerbation of symptoms; (3) factors associated with body image and DE outcomes; (4) unique challenges for marginalized and underrepresented groups. Disruptions due to the pandemic included social and functional restrictions. Although most studies reported a worsening of concerns, some participants also reported symptom improvement or no change as a result of the pandemic. Factors associated with worse outcomes included psychological, individual, social, and eating disorder‐related variables. Individuals identifying as LGBTQ+ reported unique concerns during COVID‐19.

Discussion

There is large variability in individuals' responses to COVID‐19 and limited research exploring the effect of the pandemic on body image, DE, and eating disorder outcomes using longitudinal and experimental study designs. In addition, further research is required to investigate the effect of the COVID‐19 pandemic on body image and eating concerns among minoritized, racialized, underrepresented, or otherwise marginalized participants. Based on the findings of this review, we make recommendations for individuals, researchers, clinicians, and public health messaging.

Public Significance

This review of 75 studies highlights the widespread negative impacts that the COVID‐19 pandemic and associated restrictions have had on body image and disordered eating outcomes. It also identifies considerable variations in both the improvement and exacerbation of said outcomes that individuals, researchers, clinicians, and other public health professionals should be mindful of if we are to ensure that vulnerable people get the tailored support they require.

Keywords: body image, coronavirus, COVID‐19, disordered eating, eating and feeding disorders, health inequality, isolation, lockdown, narrative synthesis, pandemic

Abstract

Objetivos

Esta revisión sistemática evaluó la influencia de la pandemia de COVID‐19 y las restricciones asociadas en los resultados en imagen corporal, la alimentación disfuncional y los trastornos alimentarios.

Método

Después del registro en PROSPERO, se realizó una búsqueda de artículos publicados entre el 1 de diciembre de 2019 y el 1 de agosto de 2021, utilizando las bases de datos PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL Plus, AMED, MEDLINE, ERIC, EMBASE, Wiley y ProQuest (disertaciones y tesis).

Resultados

Los datos de 75 estudios cualitativos, cuantitativos y de métodos mixtos se sintetizaron utilizando un enfoque integrado convergente y se presentaron narrativamente dentro de cuatro temas: (1) interrupciones debidas a la pandemia de COVID‐19; (2) variabilidad en la mejoría o exacerbación de los síntomas; (3) factores asociados con resultados de la imagen corporal y alimentarios disfuncional; (4) desafíos únicos para los grupos marginados y subrepresentados. Las interrupciones debidas a la pandemia incluyeron restricciones sociales y funcionales. Aunque la mayoría de los estudios informaron un empeoramiento de las preocupaciones, algunos participantes también informaron una mejoría de los síntomas o ningún cambio como resultado de la pandemia. Los factores asociados con peores resultados incluyeron variables psicológicas, individuales, sociales y relacionadas con el trastorno alimentario. Las personas que se identificaron como LGBTQ + informaron preocupaciones únicas durante COVID‐19.

Discusión

Existe una gran variabilidad en las respuestas de los individuos a COVID‐19 y una investigación limitada que explora el efecto de la pandemia en los resultados de la imagen corporal, la alimentación disfuncional y los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria utilizando diseños de estudios longitudinales y experimentales. Además, se requiere más investigación para investigar el efecto de la pandemia de COVID‐19 en la imagen corporal y las preocupaciones alimentarias entre los participantes minoritarios, racializados, subrepresentados o marginados. Basados en los hallazgos de esta revisión, se hacen recomendaciones para individuos, investigadores, médicos y mensajes de salud pública.

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) is an infectious respiratory illness that has claimed millions of lives globally (World Health Organization, 2021) and has had significant psychological ramifications. Individuals with disordered eating (DE) and eating disorders (EDs) may be particularly vulnerable due to the impact of distancing measures on social support and access to mental health services (Christensen, Hagan, et al., 2021; Touyz et al., 2020), as well as their problematic relationships with food in a time of food insecurity (Islam et al., 2021). Emerging evidence suggests that public health messaging associated with COVID‐19 and increased reliance on videoconferencing technologies have had a negative impact on body image (BI; Pearl & Schulte, 2021; Pikoos et al., 2021), which is closely associated with DE and ED symptoms (Smolak & Levine, 2015). A systematic investigation is therefore warranted to explore the ways in which the ongoing pandemic might impact BI, DE, and ED outcomes.

1.1. Lockdown and social distancing measures

Previous reviews have documented the negative impact of social restrictions (e.g., “lockdowns” and related physical distancing measures) associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic on psychological well‐being (Brooks et al., 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Schneider et al., 2021). Early commentary has indicated that social restrictions may be particularly challenging for individuals living with, and vulnerable to, EDs due to changes in daily routine and increased psychological distress (Rodgers et al., 2020). Furthermore, there have been notable disruptions to treatment and access to professional support (Weissman et al., 2020), though some studies have highlighted a potential benefit of increased online service provision for those not already connected with care (Simpson et al., 2021). In addition, studies have found that changes to meal patterns, food planning and buying, and physical activity have negatively impacted cognitions and behaviors across the spectrum of ED diagnoses (Hansen & Menkes, 2021; Hayes & Smith, 2021). Individuals with higher levels of psychological distress related to COVID‐19 restrictions are more likely to report increased BI concerns and DE (Flaudias et al., 2020; Swami, Horne, et al., 2021), as well as worsened ED symptomatology (Baenas et al., 2020; Chan & Chiu, 2021). This may be exacerbated by increased social media use due to limits on in‐person interactions (Pikoos et al., 2021) and increased exposure to content related to eating and appearance (Holland & Tiggemann, 2016).

1.2. Harmful messaging around quarantine weight gain

Research has also highlighted harmful messaging around weight gain during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Terms such as “covibesity” (Khan & Smith, 2020), “COVID‐15” (Pearl, 2020), and “Quarantine‐15” (Pearl & Schulte, 2021) are considered new risk factors for ED cognitions and behaviors, as well as increased BI concerns. Although considerable research has been conducted on the prevalence of weight gain during COVID‐19, less research has considered the exposure effects associated with this messaging (Pearl & Schulte, 2021). Previous literature shows a negative impact of weight stigmatizing public health messages on multiple physical and mental health outcomes, including reduced physical activity, increased binge eating, greater psychological distress, and an increase in body dissatisfaction (Bristow et al., 2020; Emmer et al., 2020; Mensinger et al., 2021). As such, media coverage of COVID‐19 related to weight gain is likely to exacerbate weight stigma and psychological distress in individuals with EDs, as well as DE behaviors and BI concerns in the general population (Lessard & Puhl, 2021).

1.3. Food insecurity and food shortages

Food insecurity (i.e., concern about, or actual changes in, food availability) has been associated with binge eating and binge eating disorder (BED), bulimia nervosa (BN), as well as general ED pathology and symptomatology (Becker et al., 2017; Hazzard et al., 2020; Lydecker & Grilo, 2019; Rasmusson et al., 2019; Zickgraf et al., 2022). Food insecurity may be exacerbated during COVID‐19 due to increased financial stress and economic limitations, as well as the “panic buying” behaviors and shortage of staple foods that characterized the initial phases of the pandemic (Khosravi, 2020; Weissman et al., 2020). These effects may be further strengthened by the pervasive media coverage about threats of food shortages (Rasmusson et al., 2019). Early research has shown increased food insecurity across multiple countries as a result of the pandemic (Mishra & Rampal, 2020; Niles et al., 2020; Zidouemba et al., 2020), but fewer studies have explored the influence of food insecurity on eating outcomes (Christensen, Forbush, et al., 2021; Coulthard et al., 2021).

1.4. Eating and BI concerns in marginalized groups

To date, most BI and ED research has been conducted with predominantly White, cisgender, and heterosexual participants, with the vast majority of studies taking place in Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries (Mikhail & Klump, 2021). ED research is often conducted with female samples, thus underrepresenting men and nonbinary or genderqueer participants (Burke et al., 2020). This is despite evidence showing that participants who identify as Black, Indigenous, or other People of Color (BIPOC) and participants from non‐WEIRD countries experience equivalent, if not higher, rates of EDs (Acle et al., 2021; Alfalahi et al., 2021). In addition, recent studies have found higher prevalence of BI and DE concerns in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning or queer (LGBTQ+) participants (Nowaskie et al., 2021). Such effects are compounded among individuals who experience multiple intersecting inequalities (e.g., Black, LGBTQ+ women; Crenshaw, 2017), and are thus likely to show the highest prevalence of BI concerns and DE (Beccia et al., 2021). A recent review on the impact of inequality factors on mental health outcomes during COVID‐19 found that certain individual characteristics, such as female gender, existing psychological health conditions, and being subjected to stigma because of one's identity as a member of an ethnic or sexual minority group predicted worse mental health outcomes (Gibson et al., 2021). However, to date, no reviews have looked specifically at BI and eating outcomes during COVID‐19 among marginalized and underrepresented populations.

1.5. The current review

The current mixed‐studies systematic review aimed to assess the influence of COVID‐19 on BI, DE behaviors, and ED outcomes. Several reviews have investigated the effect of COVID‐19 on EDs (Miniati et al., 2021; Monteleone, Cascino, Barone, et al., 2021; Sideli et al., 2021), reporting worsening of symptoms, increased levels of anxiety, and difficulties in treatment compliance during lockdown. However, little is still known about the adverse effects of the pandemic on ED outcomes and no systematic review has hitherto considered the influence of COVID‐19 on BI and DE behaviors in the general population. Furthermore, no previous reviews have adopted a mixed‐studies approach to assess the influence of COVID‐19 on BI and eating concerns. Mixed‐studies reviews maximize the findings of traditional systematic reviews (i.e., reviews summarizing qualitative or quantitative studies), and thus the ability of those findings to inform policy and practice (Harden, 2010; Stern et al., 2020). As such, the current mixed‐studies review will provide a more comprehensive depiction of the influence of COVID‐19 on BI and eating outcomes, and enhance the utility and impact of findings (Harden & Thomas, 2010; Noyes et al., 2019).

Specifically, we aimed to: (1) identify studies that assess the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic and related variables (e.g., experience of quarantine, social distancing measures, “stay at home” orders, lockdown) on BI, DE, and EDs; (2) evaluate the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic on ED‐specific and general psychopathology in individuals with EDs; (3) explore possible differences in the experiences of, and responses to, the pandemic among participants from marginalized and underrepresented populations; and (4) provide evidence‐based recommendations for individuals, researchers, clinicians, and public health messaging.

2. METHODS

This review was conducted in collaboration with researchers who have lived experience of EDs (J.S., G.P., and N.C.), clinical experience in nutrition and EDs (A.T. and E.M.), and research expertise in health psychology (B.G. and M.F.), BI (J.S., G.P., A.T., N.C., and E.M.), EDs (J.S., G.P., N.C., D.T., and E.M.), public health (B.G. and M.F.), and conducting systematic reviews (J.S., B.G., D.T., E.M., and M.F.). The review follows the updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses statement (PRISMA; Page et al., 2021) and was preregistered on PROSPERO (ref no. CRD42021247921) prior to commencement (May 10, 2021).

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

Searches were conducted for papers published between December 1, 2019 and August 1, 2021, using the databases PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, CINAHL Plus, AMED, MEDLINE, ERIC (all accessed via EBSCO), EMBASE, Wiley, and ProQuest (dissertations and theses). We did not limit searches by language or country of publication. Boolean combinations of the following search terms and their abbreviations were used: anorexia; appearance anxiety; appearance comparison; appearance concern; atypical anorexia; atypical bulimia; atypical eating disorder; binge; binge eating; body anxiety; body checking; body dissatisfaction; body dysmorphia; body dysmorphic disorder; body image; body image concern; bulimia; compulsive exercise; dietary restriction; disordered eating; eating disorder; eating pathology; eating disorders not otherwise specified; excessive exercise; feeding disorder; food intake disorder; food restriction; laxative; obsessive exercise; orthorexia; other specified feeding and eating disorders; over exercising; pica; purging; restrictive diet; rumination disorder; shape concern; vomit; weight concern; coronavirus; COVID; COVID‐19; lockdown; pandemic; quarantine; SARS‐CoV‐2; social distancing. The full search strategy can be found on the project's Open Science Framework page (https://osf.io/pz48w/).

Reference sections of the included articles were scanned to identify additional studies that met inclusion criteria. We also searched for “gray literature” and unpublished studies uploaded to PsyArXiv or registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, as well as conference abstracts (Appearance Matters 9 Online Conference, July 13–15, 2021; International Conference on Eating Disorders, June 10–12, 2021) to ensure we captured all relevant research, given the timeliness of COVID‐19. In addition, Emeritus Professor Michael Levine forwarded our request for published and unpublished research to the Levine Prevention/Sociocultural Factors TinyLetter email group, consisting of approximately 1060 researchers across 49 countries who are actively involved in BI and ED research.

2.2. Study eligibility criteria

We included papers that examined the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic or variables directly related to the pandemic (e.g., experience of quarantine, social distancing measures, “stay at home” orders, lockdown, COVID‐19‐related anxiety or stress) on BI, DE, and ED outcomes. BI outcomes included, for example, experiences of weight stigma, appearance concerns, and body anxiety. DE and ED outcomes included onset of, exacerbation of, or change in specific symptoms (e.g., binge eating, purging, compulsive exercise, food restriction), mental health and well‐being in individuals with diagnosed or undiagnosed EDs (e.g., anxiety, stress, depression, psychological distress, negative affect), and treatment outcomes (e.g., adherence to treatment, treatment efficacy). This was a mixed‐studies review; as such, we included controlled trials, cohort studies, cross‐sectional studies, case reports, and qualitative studies that examined the influence of the COVID‐19 pandemic on target outcomes. We excluded: (1) review papers, commentaries, opinion pieces, and editorials; (2) studies that did not assess the direct relationship between the COVID‐19 pandemic and target outcomes (e.g., studies that were conducted during the pandemic, but did not examine the influence of COVID‐19 or related predictors on target outcomes, or studies that did not compare current levels of BI concerns or ED symptoms with prepandemic levels); and (3) studies related to eating habits, dieting, or exercise unrelated to BI or ED symptomatology (e.g., adherence to a Mediterranean diet, changes in physical activity in the general population).

2.3. Study selection

Two authors (J.S. and G.P.) screened titles and abstracts of retrieved papers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined above. Duplicates and irrelevant papers were removed. J.S. and A.T., and G.P. and B.G. independently screened 50% of the full texts that were identified as potentially eligible. The authors held regular meetings to discuss uncertainties and clarify eligibility criteria. Any discrepancies in selecting the final papers for inclusion were resolved through discussion and consultation with the full review team.

2.4. Data extraction

Data extraction was completed by four researchers who cross‐checked each other's data extraction (J.S., A.T., G.P., and B.G.). In line with Harden (2010), we used two separate protocols for quantitative and qualitative data. Data extracted for quantitative and qualitative studies are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. For studies that described statistically significant outcomes, a p < .05 was considered significant.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of quantitative studies

| Author(s) (year) | Country | Participants | Methods | Key findings | Study quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% female) a | Age M (SD) | Race and ethnicity | Sexual orientation | Socioeconomic status | Diagnosis | Design | Measures | ||||

| Akgül et al. (2021) | Turkey | 38 (95%) | 15.1 (1.6) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN‐R n = 26; AN‐BP n = 5; AAN n = 3; BN n = 3; OSFED n = 1 | Cross‐sectional | ED examination; depression; anxiety; obsessive–compulsive symptoms | 42% reported improved ED symptomatology, 37% reported no change, 21% reported worse ED symptomatology from pre‐ to during lockdown; 24% reported that lockdown affected access to ED‐related healthcare; depression score had the highest predictive value for ED behavior (r 2 = .537) | 3 |

| Baceviciene and Jankauskiene (2021) | Lithuania | 230 (79%) | 23.9 (5.4) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Longitudinal | Attitudes toward appearance; BI; ED examination; self‐esteem | No change in DE or self‐esteem from pre‐ to during lockdown; body appearance evaluation (women only), media pressures (women only), and internalization of thin/low body fat appearance standards (men: d = 1.46; women: d = 1.18) increased from pre‐ to during lockdown | 3 |

| Baenas et al. (2020) | Spain | 74 (96%) | 32.1 (12.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 19; BN n = 12; BED n = 10; OSFED n = 33 | Cross‐sectional | ED inventory; food addiction; symptom checklist; temperament and character; telephone survey | 26% reported worsened symptoms during confinement (highest in AN and OSFED), 74% reported improvements or no change; patients with worsened symptoms reported lower self‐directedness (d = 0.51) and higher prevalence of future concerns (d = 0.51), nonadaptive reactions (d = 0.79), symptoms of anxiety (d = 0.89) and depression (d = 0.96), adverse situations (d = 0.62), and familiar conflict (d = 0.68) | 2 |

| Bellapigna et al. (2021) | United States | 239 (gender: 79% women; 1.3% nonbinary/nonconforming) | 24.7 (11.1) | 6.7% Black/African American; 10% Hispanic; 5.9% Asian; 67.8% White; 9.2% multiracial/biracial; 0.4% “other” | Not reported | Education: 25.6% high school degree or equivalent; 46.2% some college; 10.1% 2‐year degree; 11.8% bachelor's degree; 3.4% master's degree; 2.1% doctorate; 2.8% other | 6.3% diagnosed with ED | Cross‐sectional | Need for structure; loneliness; social networking; body appreciation; eating attitudes; social phobia; patient health | 64% reported more disturbances in BI during COVID; loneliness (β = −.138), negative BI (β = .253), and social media exposure (β = −.161) predicted DE; loneliness (β = −.485), negative BI (β = .123), and social media exposure (β = −.154) predicted depressive symptoms | 3 |

| Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2020) b | United Kingdom | 129 (94%) | 29.3 (9.0) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 62% current ED/relapse; in recovery 6.2% <3 m, 6.2% 3–12 m, 25.6% >12 m | Cross‐sectional | Mental well‐being; perceived stress; social support; sense of control; rumination | 87% reported worsened symptoms as a result of COVID, 30% reported symptoms were much worse, 2% reported slight improvement, 9% reported no change; changes in living situation, social isolation, usual support network(s), physical activity, and time spent online impacted ED symptoms | 3 |

| Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2021) b | United Kingdom | 58 (98%) | 30.9 (11.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 63.8% current ED/relapse; 36.2% in recovery; AN n = 28; BN n = 7; OSFED n = 3; BED n = 2; symptoms of multiple EDs n = 12; undisclosed ED n = 7 | Longitudinal | Mental well‐being; perceived stress; social support; sense of control; rumination | 15.5% reported relapsing, 19% reported recovering, and 65.5% reported no change in ED status from during to postlockdown; higher perceived control associated with recovery | 2 |

| Breiner et al. (2021) | United States | 159 (91%) | 27.6 (11.7) | 90.6% White; 5% Hispanic/Latino; 6.3% Asian; 0.6% American Indian or Alaska Native; 0.6% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; 1.3% Native American | 74.8% heterosexual; 2.5% homosexual; 14.5% bisexual | Education: 5% high school graduate; 8.8% less than 2 years of college; 0.6% technical or vocational program; 6.9% associate degree; 62.3% college graduate; 14.5% master's degree; 1.9% doctorate | AN n = 22; BN n = 8; BED n = 4; “other” n = 3 | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | ED examination; exercise behaviors; exercise motives; ED diagnosis | No significant changes in exercise or eating pathology from pre‐ to during COVID; eating pathology increased in participants with a prior ED diagnosis (d = 0.26), but decreased in participants without a prior ED diagnosis (d = −0.14); there were decreases in episodes of eating more than usual (d = −0.23) and loss of control over eating (d = −0.23), but no changes in objective binge eating (d = −0.04), self‐induced vomiting (d = −0.05), or laxative use (d = −0.14); participants reported increased endorsement of pressure to get in shape from pre‐ to during the pandemic | 3 |

| Buckley et al. (2021) b | Multiple | 204 (86%) | 27.0 (8.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 10.7% current ED; 32.8% previous diagnosis (AN n = 29; BN n = 11; ON n = 9; BED n = 7; “other” n = 11) | Cross‐sectional | Eating attitudes; BI and food relationship | 34.8% reported worse BI, 50.5% reported no change, and 14.6% reported better BI from pre‐ to during COVID; 32.8% reported worse relationship with food, 53.0% reported no change, and 14.1% reported better relationship with food from pre‐ to during COVID | 3 |

| Castellini et al. (2020) | Italy | Patients/healthy controls: 74/97 (sex assigned at birth: 100/100% female) | Patients/healthy controls: 31.7/30.5 (12.8/10.9) | 100% White | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 37; BN n = 37 | Longitudinal | Brief symptom inventory; ED examination; psychological distress | Patients reported increased compensatory exercise during lockdown (AN: d = 0.32; BN: d = 0.30); patients with BN/previously remitted patients reported increased binge eating after lockdown (d = 0.32); household arguments (d = 0.62) and fear for safety of loved ones (d = 0.67) predicted increased symptoms; patients with BN reported more severe COVID‐related posttraumatic symptoms than patients with AN and healthy controls, predicted by childhood trauma (β = .34) and insecure attachment (β = .57) | 1 |

| Cecchetto et al. (2021) | Italy | 365 (73%) | 35.1 (13.6) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Binge eating screener; alexithymia; anxiety; eating behaviors; patient health; perceived stress | Binge eating and emotional eating decreased from during to postlockdown; emotional eating was predicted by higher depression, anxiety, lower quality of personal relationships, and lower quality of life; increase in binge eating was predicted by higher stress | 2 |

| Chan and Chiu (2021) | Hong Kong | 316 (71%) | 25.1 (5.0) | Not reported | Not reported | 88.3% university educated | n/a | Cross‐sectional | ED screening; patient health; anxiety; psychological well‐being; eating behaviors and emotions | Among individuals with elevated depression, those who attributed depression to COVID reported higher levels of symptoms; no effect on anxiety | 3 |

| Christensen, Forbush, et al. (2021) | United States | 579 (gender identity: 76% women; 2% “other”) | 21.8 (5.3) | 9% Hispanic; 91% non‐Hispanic; 84.1% White; 3.5% Black/African American; 1% American Indian/Alaskan Native; 5.5% Asian/Pacific Islander; 5.2% multiracial; 0.7% not disclosed | Not reported | Years of posthigh school: 20.3% <1 year; 18.7% 1 year; 19.4% 2 years; 22.0% 3 years; 9.9% 4 years; 2.4% 5 years; 5.0% 6+ years 5%; 2.3% continuing education; food insecurity: 52.8% none; 6.6% household food insecurity; 40.6% individual food insecurity | AN n = 4; BN n = 75; BED n = 14; OSFED n = 135; no ED diagnosis n = 344 | Cross‐sectional | Clinical impairment; ED diagnosis; food insecurity | Students with food insecurity showed higher prevalence of ED diagnoses and reported greater frequency of objective binge eating, compensatory fasting, and ED‐related impairment compared with individuals without food insecurity; there were no differences in food insecurity before or during the beginning of the COVID pandemic; participants who identified as Black were significantly more likely to report individual food insecurity relative to other racialized groups | 2 |

| Conceição et al. (2021) | Portugal | COVID/non‐COVID group: 35/66 (94/83%) | COVID/non‐COVID group: 50.8/50.1 (12.4/10.7) | Not reported | Not reported | Education (COVID/non‐COVID group): ≤6 years (42.9/31.8%; 9–12 years (34.3/48.5%); college degree (22.9/19.7%); professional status: student (2.9/1.5%); employed (62.9/57.6%); unemployed (11.4/25.8%); retired: (22.9/15.2%) | n/a | Cohort | ED examination; repetitive eating; depression, anxiety, stress; impulsivity | Participants assessed post‐COVID showed a greater increase in weight concern scores (ƞ 2 p = 0.094) and repetitive eating (ƞ 2 p = 0.076) compared with participants assessed pre‐COVID; no difference between groups in shape concern, food concerns, or restraint eating | 1 |

| Coulthard et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 620 (88%) | 39.9 (14.0) | 88% White‐British/European; 6% Asian/British Asian; 1% Black/Black British; 4% “other”; 1% not disclosed | Not reported | Occupation: 39% professional; 21% intermediate; 15% manual; 25% not working; food insecurity: 65% none; 29% mild; 6% moderate/severe | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Food consumption; ED symptoms; coping strategies; anxiety; food insecurity | Emotional eating decreased from pre‐ to during lockdown; women and those isolating at home were more likely to report higher emotional eating during lockdown; there was no differences in eating behavior based on occupation or ethnicity; higher emotional eating during lockdown associated with higher BMI, higher prelockdown emotional eating, and maladaptive coping strategies | 2 |

| Czepczor‐Bernat et al. (2021) | Poland | 671 (100%) | 32.5 (11.4) | 98.8% White; 0.3% mixed race; 0.9% “other” | 91.3% heterosexual; 1.6% lesbian; 4.9% bisexual; 0.7% pansexual/queer; 0.9% asexual; 0.6% “other” | Education: cluster 1 32% secondary/technical school; cluster 2 32% secondary/technical school; cluster 3 37% master's degree; cluster 4 45% master's degree | n/a | Cross‐sectional | COVID‐related stress; COVID‐related anxiety; ED inventory; BI | Higher levels of ED symptoms and negative BI were observed in women with excess body weight, high anxiety, and stress related to COVID as compared with women with a healthy body weight and with low levels of anxiety and stress | 3 |

| Félix et al. (2021) | Portugal | 24 (100%) | 50.9 (12.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Education: 29.2% elementary school; 25.0% middle school; 12.5% high school; 33.3% college degree; employment: 66.7% employed; 8.3% unemployed; 25.0% retired | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Depression, anxiety, stress; impulsivity; DERS; ED examination; loss of control over eating; repetitive eating; ED symptoms; impact on emotions, eating, and weight; COVID impact | Living with fewer people, higher difficulties in dealing with emotionally activating situations, and higher fear of gaining weight during lockdown associated with greater fear of gaining weight, greater fear of losing control over eating, and greater DE psychopathology | 2 |

| Fernández‐Aranda, Munguía, et al. (2020) | Spain | 121 (86%) | 33.7 (15.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 55; BN n = 18; OSFED n = 14 | Cross‐sectional | COVID isolation eating scale | Patients with AN reported a positive response to treatment during confinement; no significant changes found in patients with BN; patients with OSFED reported an increase in eating symptomatology and psychopathology; patients with AN reported greatest dissatisfaction and accommodation difficulty with remote therapy | 3 |

| Fernández‐Aranda, Casas, et al. (2020) Study 1 | Spain | 32 (91%) | 29.2 (range 16–49 years) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 13; BN n = 10; BED n = 4; OSFED n = 5 | Cross‐sectional | Telephone survey | Most patients presented worries about increased uncertainties, such as the risk of COVID infection of themselves or their loved ones, the negative impact on their work, and their treatment; 38% reported impairments in ED symptomatology; 56% reported additional anxiety symptoms | 3 |

| Flaudias et al. (2020) | France | 5738 (75%) | 21.2 (4.5) | Not reported | Not reported | University students, 48.8% with scholarship | 38.3% at risk for ED symptoms | Cross‐sectional | Anxiety and depression; perceived stress; ED inventory; ED screening; ideal body stereotypes | Greater likelihood of binge eating (BE) and dietary restriction (DR) over past week and/or future intentions to binge eat (FBE) and restrict (FDR) associated with lockdown‐related stress (all odds ratios [OR]; BE = 1.12; DR = 1.17; FBE = 1.33; FDR = 1.12), exposure to COVID‐related media (BE = 1.02; DR = 1.05; FBE = 1.20; FDR = 1), female gender (BE = 1.40; DR = 1.79; FBE = 1.09; FDR = 1.48), greater levels of anxiety (BE = 1.09; DR = 1.11; FBE = 0.95; FDR = 1.04) and depression (BE = 1.14; DR = 0.94; FBE = 1.40; FDR = .95), low impulse regulation (BE = 1.10; DR = 1.04; FBE = 1.23; FDR = 1.12), higher BMI (BE = 1.26; DR = 1.07; FBE = 1.19; FDR = 1.04), body dissatisfaction (BE = 1.08; DR = 1.80; FBE = 0.84; FDR = 2.05), and concurrent probable ED (BE = 2.82; DR = 2.65; FBE = 2.11; FDR = 2.58) | 3 |

| Giel et al. (2021) | Germany | 42 (81%) | 45.5 (12.6) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | BED n = 17 | Longitudinal | ED examination; perceived stress; binge eating frequency; depression; emotion regulation; coherence | Binge eating frequency (χ 2 = 15.22), general ED pathology (χ 2 = 35.52), and depressive symptoms (χ 2 = 5.41) increased from pre‐ to post‐COVID; individuals scoring high on reappraisal and sense of coherence scored lower on general ED pathology | 3 |

| Graell et al. (2020) | Spain | Day hospital/outpatient clinic: 27/338 (93/87%) | Day hospital/outpatient clinic: 13.2/14.7 (3.0/2.3) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | ARFID n = 48; AN n = 255; BN n = 26; OSFED n = 37 | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Outpatient and face‐to‐face consultations | 42% reported reactivation of ED symptoms following COVID confinement (>adolescents); 68% of patients and their families reported onset of confinement and 41% reported social isolation from peers as influencing factors for admission | 2 |

| Gullo and Walker (2021) | United States | 143 (gender: 53% ciswomen; 1% transmen; 0% transwomen; 1% nonbinary) | 77% 18–44 years | 79.7% White: 9.8% Black: 4.2% Asian; 3.5% Latinx: 1.4% mixed; 0.7% Native American; 0.7% “other” | Not reported | Household annual income (USD): 2.8% <15,000; 9.1% 15,000–29,999; 11.9% 30,000–49,999; 23.8% 50,000–75,999; 16.8% 75,000–99,999; 17.5% 100,000–150,000; 14.0% >150,000; 4.2% prefer not to answer | n/a | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Depression, anxiety, stress; BI; binge eating; body satisfaction | Time spent videoconferencing increased from pre‐ to post‐COVID; appearance dissatisfaction increased (β = .75), but appearance orientation decreased (β = .75) following lockdown; no change in binge eating from pre‐ to postlockdown; videoconferencing time did not predict BI or binge eating postlockdown | 3 |

| Haddad et al. (2020) | Lebanon | 407 (51%) | 30.6 (10.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Education: 90.9% university level; 9.1% secondary school or lower | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Boredom; ED examination; quarantine/ confinement stressors; fear of COVID; anxiety; physical activity | Dietary restraint (DR), eating concerns (EC), shape concerns (SC) and weight concerns (WC) were associated with female gender (all β; EC = 0.52; SC = 0.19; WC = 0.20), higher anxiety (EC = 0.04; SC = 0.23; WC = 0.19), sense of insecurity (EC = 0.41), greater fear of COVID (DR = 0.02; SC = 0.20; WC = 0.12), higher BMI (DR = 0.05; EC = 0.06; SC = 0.39; WC = 0.41), physical activity (DR = 1.04; EC = 0.43; SC = 0.15; WC = 0.19), and a higher number of adults living together in quarantine/confinement (SC = 0.10; WC = 0.15) | 2 |

| Haddad et al. (2021) | Lebanon | 407 (51%) | 30.6 (10.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Household monthly income (USD): 31.0% no income; 20.4% <1000; 29.1% 1000–2000; 19.3% >2000 | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Boredom; ED examination; quarantine/ confinement stressors; fear of COVID; anxiety; physical activity; perceived weight change | Longer confinement duration (OR = 1.07), higher anxiety (OR = 1.05), and higher eating concerns (OR = 1.81) associated with higher weight change perception; greater fear of COVID (OR = 0.96) and higher self‐reported weight change (OR = 0.47) associated with lower weight change perception | 2 |

| Jordan et al. (2021) | United States | 140 (89%) | 39.8 (6.9) | 88.4% White | Not reported | 82.2% middle to upper‐middle class | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Perceived stress; concern about weight gain; ED examination; emotional eating |

Disordered eating associated with concern about weight gain before (β=.18) and during (β=.32) COVID; stress and concern about weight gain during COVID predicted variance in eating pathology among caregivers (r 2 = 0.48). |

2 |

| Keel et al. (2020) | United States | 90 (88%) | 19.5 (1.3) | 22% Latinx; 78% White; 12% Black/African American; 4% Asian; 1% American; Indian/Alaskan Native; 3% “other” | 89% heterosexual | Not reported | n/a | Longitudinal | Weight perception; physical activity; eating; concerns about weight and shape; body, eating, exercise comparisons; ED diagnosis; screen time | Participants reported increased body weight (d = 0.23), eating (d = 0.54), screen time (d = 1.08), and concerns about weight/shape (d = 0.93) and eating (d = 0.79), and decreased physical activity (d = −0.63) from pre‐ to post‐COVID; no change in weight or BMI, but participants reported shifts in body weight perception from pre‐ to post‐COVID | 3 |

| H. Kim, Rackoff, et al. (2021) | United States | Pre‐/during COVID: 3643/4970 (sex assigned at birth: 73/70% female; 0.05/0.02% intersex; gender identity: 70/68% women; 4/2% trans, nonconforming, or self‐identify) | Not reported | Pre‐/during COVID: 12/10% Hispanic; 88/90% non‐Hispanic; 72/75% White; 9/6% Black/African American; 10/14% Asian; 0.7/0.5% American Indian or Alaskan Native; 0.4/0.2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander; 8/5% multiracial | Pre‐/during COVID: 71/81% heterosexual; 29/19% lesbian, gay, bisexual, queer, questioning, or self‐identify | Not reported | Pre‐/during COVID: AN n = 64/88; BN/BED n = 320/643 | Longitudinal | Anxiety; posttraumatic stress; patient health; presence of EDs; insomnia; alcohol use | Depression (χ 2 = 21.67), alcohol use disorder (χ 2 = 67.26), BN/BED (χ 2 = 20.83), and comorbidity (χ 2 = 6.83) were greater during than before COVID; posttraumatic stress disorder was lower during than pre‐COVID (χ 2 = 5.46); no differences in anxiety, insomnia, AN, or suicidality between pre‐ and during COVID; no effect of gender, ethnicity/racialized group, or sexuality on EDs | 2 |

| S. Kim, Wang, et al. (2021) | United States | 7317 (59%) | 50.6 (16.1) | 64.7% non‐Hispanic White; 7.9% non‐Hispanic Black; 16.8% Hispanic; 5.1% non‐Hispanic Asian; 0.9% Native American; 4.5% “other”; 0.2% not disclosed | Not reported | Education: 5.4% <high school; 16.7% high school or less; 22.8% some college; 14.3% associate degree; 24.3% bachelor's degree; 16.5% advanced college degree | Diagnosed ED n = 157; unsure about ED status n = 122 | Longitudinal | Patient health; perceived stress; loneliness | Individuals with EDs/unsure EDs reported higher levels of psychological distress (all B; EDs = 2.18; unsure EDs = 2.01), stress (EDs = 1.17; unsure EDs = 2.08), and loneliness (unsure EDs = 0.90) compared to those without EDs; those unsure about their EDs reported initial decreases in stress and loneliness, but started increasing again since institution of virus containment procedures; levels of loneliness among those with EDs increased initially then began to decrease; individuals with EDs showed steady decreases in stress; identifying as Black, older age, and higher education associated with lower psychological distress (Black = −0.59; age = −0.03; education = −0.03), stress (age = −0.04; education = −0.13), and loneliness (Black = −0.10; age = −0.01); female gender and identifying as Asian associated with higher psychological distress (female = 0.61; Asian = 0.29), stress (female = 0.56; Asian = 1.07), and loneliness (female = 0.14) | 1 |

| Koenig et al. (2021) | Germany | Pre/postlockdown: 324/324 (69/69%) | 14.9 (1.9) | Not reported | Not reported | Family affluence (pre‐/postlockdown): low (1.9/1.9%); medium (24.4/ 21.6%); high (73.9/76.5%) | n/a | Longitudinal | Strengths and difficulties; patient health; weight concerns; ED examination; quality of life; suicidality | No differences between pre‐ and postlockdown samples in emotional and behavioral problems, depression, thoughts of suicide/suicide attempts, ED symptoms, or quality of life | 1 |

| Larkin (2021) | United States | 290 (not reported) | Range 18–25 years | 0.3% American Indian/Alaskan Native; 2.8% Asian; 10.3% Black/African American; 14.5% Hispanic/Latino; 1.7% biracial/multiracial; 80.7% White | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Physical activity, social media use; subjective well‐being; BI | 32.7% increase in negative BI perceptions from pre‐ to post‐COVID | 3 |

| Leenaerts et al. (2021) | Belgium | 15 (100%) | Median (IQR) = 23 years (21.5–25.5) | 87% European; 13% Asian | Not reported | Not reported | BN | Longitudinal | Affect; location; social context; binge eating frequency | Patients reported higher negative affect (β = .15), lower positive affect (β = −.10), and changes in surroundings and social context (at home: β = 3.19; with housemates: β = 3.91; with friends: β = −2.45; with family: β = .99; with partner: β = −2.39) from pre‐ to postlockdown; changes of negative affect associated with binge eating frequency during lockdown (β = .61) | 2 |

| Lessard and Puhl (2021) | United States | 452 (gender identity: 55% women; 2% transgender; 1% “other”; sex assigned at birth: not reported) | 14.9 (2.1) | 69.9% White; 8.2% Black/African American; 8.0% Latinx; 6.6% multiethnic; 5.5% Asian/Pacific Islander; 1.8% “other” | Not reported | 72% had a parent with a college degree or higher | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Body dissatisfaction; exposure to weight stigma on social media; experienced weight stigma | 53% reported increased exposure to weight stigmatizing social media content; 41% reported increased body dissatisfaction from pre‐ to post‐COVID (>girls; higher weight), 49% reported no change, 10% reported a decrease | 3 |

| Lin et al. (2021) | United States | Not reported | Range 8–26 years | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Patients with any ED diagnosis | Longitudinal | COVID‐related trends in ED care‐seeking | Inpatient admissions, hospital bed‐days, outpatient inquiries increased over time post‐COVID compared to stable volume pre‐COVID; outpatient assessments decreased initially following COVID‐related limitations, then rebounded | 2 |

| Machado et al. (2020) | Portugal | 43 (95%) | 27.6 (8.5) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 20; BN n = 14; BED n = 2; OSFED n = 7 | Longitudinal | ED examination; clinical impairment; impulsivity; difficulties in emotion regulation; COVID impact | Of 26 patients in treatment 31% remained unchanged, 27% deteriorated, and 42% improved; of 17 participants not in treatment 53% remained unchanged, 18% deteriorated, and 29% improved from during to postlockdown; higher impact correlated with ED symptoms, impulsivity (r = .380), psychopathology (r = .451), emotion regulation difficulties (r = .393) and clinical impairment (r = .569) | 3 |

|

Martínez‐de‐Quel et al. (2021) |

Spain | 161 (37%) | 35.0 (11.2) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Longitudinal | Eating attitudes | No change in ED risk from before to during COVID lockdown | 2 |

| Meda et al. (2021) | Italy | 358 (80%) | 21.3 (2.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Longitudinal | ED inventory; eating habits; obsessive–compulsive symptoms; anxiety; depression | Only students with ED history reported an increase in ED symptomatology from pre‐ to postlockdown (β = .1). | 3 |

| Monteleone, Cascino, Marciello, et al. (2021) | Italy | 312 (gender identity: 96% women; 0.3% nonbinary) | AN: 26.9 (10.3); other EDs: 32.3 (13.5) | Not reported | Not reported | Employment (AN/other EDs): paid job (26/39%); student (56/49%) | AN n = 179; BN n = 63; BED n = 48; OSFED n = 22 | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Factors related to COVID concerns; illness duration; treatment‐related variables; ED psychopathology | General (GP) and specific psychopathology (SP) worsened from pre‐ to postlockdown; perceived low quality of therapeutic relationships (GP: β = −.16; SP: β = −.22), fear of contagion and increased isolation (GP: β = .22; SP: β = .22), reduced satisfaction with relationships (SP: β = .24), and reduced social support (GP: β = .23) associated with worsened psychopathology; no effect of intimate relationships, illness duration, diagnosis, economic change, or type of treatment | 2 |

| Monteleone, Marciello, et al. (2021) | Italy | 312 (gender identity: 96% women; 0.3% nonbinary) | 29.2 (12.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 179; BN n = 63; BED n = 48; OSFED n = 22 | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Anxiety; posttraumatic stress; obsessive–compulsive symptoms; patient health; ED inventory | General and specific psychopathology worsened from pre‐ to postlockdown; symptoms persisted postlockdown, apart from suicide ideation; individuals with AN reported higher anxiety, obsessive–compulsive symptoms, suicide ideation, and physical activity levels, and lower binge eating; no effect of age or illness duration | 2 |

| Nisticò et al. (2021) | Italy | 40 (95%) | 30.9 (14.2) | 100% White | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 15; BN n = 11; BED n = 14 | Longitudinal | ED examination; depression, anxiety, stress; psychological distress | Posttraumatic stress (IES‐R total score: η 2 p = 0.145) and ED symptoms (η 2 p = 0.142–0.249) improved from during to postlockdown; no change in stress, anxiety, or depression | 2 |

| Pfund et al. (2020) | United States | 438 (gender identity: 100% women; 434 ciswomen and 4 transwomen) | 31.3 (12.7) | 11% African American/Black; 22% Asian/Asian American; 52% European American/White; 10% Latinx American/Hispanic; 2% Middle Eastern, and 3% “other”/not disclosed | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Body surveillance; appearance comparison; body satisfaction | Time video chatting increased from pre‐ to post‐COVID (d = 0.53). Time video chatting not associated with appearance satisfaction; self‐objectification moderated relationship between time video chatting and appearance satisfaction (B = −.04 for face satisfaction and B = −.02 for body satisfaction); participants who spent more time engaged with their families over video chatting services reported greater face (r = .21) and body (r = .17) satisfaction | 2 |

| Phelan et al. (2021) | Ireland | 1031 (sex assigned at birth: 100% female) | 36.7 (6.6) | 97% White; 2% Asian; 0.3% Black; 0.5% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Mental health symptoms, diet, exercise | Participants reported an increase in binge eating from pre‐ to during COVID | 3 |

| Philippe et al. (2021) | France | 498 (52%) | 7.3 (2.3) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Eating difficulties; eating behavior; parental feeding practices | Parents reported an increase in their child's emotional overeating, food responsiveness, food enjoyment, and appetite, but no change in their child's pickiness from pre‐ to during lockdown; boredom predicted increased food responsiveness (β = .14), emotional overeating (β = .20), and snack frequency between meals (β = .28) | 2 |

| Phillipou et al. (2020) | Australia | 5469 (96% women; 3% preferred to self‐describe) | 30.5 (8.2) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 88; BN n = 23; BED n = 6; OSFED n = 4; UFED n = 68; recovering/in recovery n = 10 | Cross‐sectional | Depression, anxiety, stress; ED examination | Participants with ED history reported increased restricting (64.5%), binge eating (35.5%), purging (18.9%), and exercise behaviors (47.3%); participants without ED history reported both increased restricting (27.6%) and binge eating behaviors (34.6%), but decreased exercise (43.4%) from pre‐ to during COVID | 3 |

| Pikoos et al. (2020) | Australia | 216 (gender: 88% women; 0.01% “other”) | 32.5 (11.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Dysmorphic concern; depression, anxiety, stress; appearance‐focused behaviors | Appearance‐focused behaviors decreased in participants with low dysmorphic concerns, but not in participants with high dysmorphic concerns from pre‐ to during COVID; living alone, younger age, higher dysmorphic concern, and greater distress over beauty service closure predicted appearance‐focused behaviors | 2 |

| Puhl et al. (2020) | United States | 584 (gender identity: 64% women; 1% “other”) | 24.6 (2.0) | 30.2% White; 16.8% African American/ Black; 17.1% Hispanic; 24.3% Asian American; 11.6% “other” | Not reported | 31.5% lower class; 20.0% lower middle class; 17.4% middle class; 19.4% upper middle class; 11.7% upper class (assumed self‐report) | n/a | Longitudinal | Psychological distress; eating behaviors; binge eating; physical activity; weight stigma | Pre‐COVID experiences of weight stigma predicted higher levels of depressive symptoms (β = .15), stress (β = .15), eating as a coping strategy (β = .16), and an increased likelihood of binge eating during COVID (OR = 2.88), but were unrelated to physical activity; no effect of gender | 2 |

| Ramalho et al. (2021) | Portugal | 254 (83%) | 35.8 (11.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Education: 13.0% high school; 27.2% bachelor's degree; 59.8% master's degree/doctorate | n/a | Cross‐sectional | DE behaviors; COVID impact; depression, anxiety, stress; ED symptoms | Psychosocial impact of COVID predicted DE behaviors mediated through psychological distress (>women; younger age) (β = .10); psychosocial impact of COVID associated with emotional eating (r = .23) and uncontrolled eating (r = .18) | 2 |

| Richardson et al. (2020) b | Canada | 439 (gender: 80% women; 2% transgender; 11% did not disclose) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 83; BN n = 44; ARFID n = 4; BED n = 66; OSFED n = 9; undisclosed/ undiagnosed n = 233 | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Telephone survey | Service utilization, ED symptoms, anxiety, and depression increased from pre‐ to during COVID among patients with EDs | 3 |

| Robertson et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 264 (78%) | Range 18–79 years | 92% White | Not reported | Not reported | 13.8% current or past ED diagnosis | Cross‐sectional | Perceived change in eating, exercise, and BI; patient health | 53% reported more difficulty regulating eating; 60% reported more preoccupation with food/eating; 50% reported exercising more; 68% reported thinking more about exercise; 49% reported more appearance concerns from pre‐ to during lockdown (>women; participants with past/current ED); psychological distress was correlated with finding it more difficult to control/regulate one's eating (rs = .36), being more preoccupied with food/eating (rs = .29), thinking more about exercise (rs = .17), and being more concerned about one's appearance (rs = .41) | 3 |

| Scharmer et al. (2020) | United States | 295 (65%) | 19.7 (2.0) | 48% White; 21% African American; 11% Asian; 14% Hispanic/Latino; 1% Native American; 1% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 3% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | ED examination; compulsive exercise; anxiety; fear of illness and virus evaluation; intolerance of uncertainty; physical activity | COVID anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty was associated with ED pathology, but not compulsive exercise; trait and COVID intolerance of uncertainty moderated associations between COVID anxiety and compulsive exercise and ED pathology; COVID anxiety was more strongly related to compulsive exercise and ED pathology for individuals with lower intolerance of uncertainty | 3 |

| Schlegl, Maier, et al. (2020) | Germany | 159 (100%) | 22.4 (8.7) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Psychological consequences of COVID | >70% reported that eating, shape and weight concerns, drive for physical activity, loneliness, sadness, and inner restlessness increased from pre‐ to during COVID and access to in person care decreased; participants reported daily routines, day planning, and enjoyable activities as the most helpful coping strategies; reduction in overall ED symptoms/taking on responsibility to recover, reduction in specific ED symptoms, more flexibility regarding meals and foods, wake‐up call/will to live, trying out therapy content, and accepting uncertainty in life were reported as positive impacts of COVID | 3 |

| Schlegl, Meule, et al. (2020) | Germany | 55 (100%) | 24.4 (6.4) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | BN | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Psychological consequences of COVID | 49% reported deterioration of ED symptomatology and 62% reported reduced quality of life; frequency of binge eating increased in 47% of patients, self‐induced vomiting in 36%, laxative use in 9%, and diuretic abuse in 7%; face‐to‐face psychotherapy decreased by 56%, videoconferencing therapy was used by 22% of patients; enjoyable activities, virtual contact with friends, and mild physical activity rated as most helpful coping strategies | 3 |

| Serin and Koç (2020) | Turkey | 1064 (59%) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Eating behaviors; depression | External eating, but not emotional or restrictive eating, higher in participants who reported self‐isolating, compared to those who did not (>women) | 2 |

| Spettigue et al. (2021) | Canada | 48 (gender: 83% ciswomen; 2% transwomen; 4% transmen) | 14.6 (1.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN‐R n = 24; AN‐BP n = 7; ARFID n = 7; AAN n = 6; BN n = 1; UFED n = 3 | Cohort | ED examination; eating attitudes; clinical impairment | 40% cited pandemic as trigger for ED; inpatient admissions, emergency room consultation requests, and outpatient referrals deemed “urgent” were higher during COVID compared to pre‐COVID; compared to 2019 ED patients, ED patients in 2020 reported worse clinical impairment from ED symptoms (d = 0.44) and higher levels of eating restraint (d = 0.63) | 2 |

| Stoddard (2021) b | United States | 69 (gender identity: 96% women; 4% nonbinary) | 96% 18–34 years | 91% White; 7% Black; 3% Asian; 6% Latina; 3% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | Previous/current: 83/71% BI disturbance; 84/51% DE habits; 72/13% ED | Cross‐sectional | ED/BI status/concern level; impact of COVID; experiences of ED/BI; coping mechanisms | 84% reported concern about how their weight/bodies might be affected by COVID; 59% reported that their BI/ED worsened from pre‐ to post‐COVID; 78% reported that their relationships with their bodies have changed (70% negative, 26% positive, 4% neutral) | 2 |

| Swami, Horne, et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 506 (gender identity: 44% women) | 34.3 (11.4) | 88.5% White | 89.1% heterosexual | Education: 10.9% high school; 27.9% advanced qualification; 38.3% undergraduate degree; 19.0% postgraduate degree; 3.9% other | n/a | Cross‐sectional | Perceived stress; ED inventory; body attitude; COVID‐related stress and anxiety | In women, COVID‐related anxiety associated with body dissatisfaction and COVID‐related anxiety and stress was associated with drive for thinness; in men, COVID‐related anxiety was associated with low body fat dissatisfaction and COVID‐related anxiety and stress was associated with muscularity dissatisfaction | 2 |

| Swami, Todd, et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 600 (gender identity: 49% women) | 34.6 (12.3) | 85% White; 9% Asian; 2% Black; 4% mixed race; 0.3% “other” | 87% heterosexual; 3% gay/lesbian; 8% bisexual; 2% identified with another orientation | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional | BI disturbance; COVID‐related stress; self‐compassion | COVID‐related stress associated with greater BI disturbance, mediated by lower self‐compassion; self‐compassion did not moderate effects of stress on BI disturbance | 2 |

| Tabler et al. (2021) b | United States | 411 (74% women; 5% transgender, genderqueer, or nonbinary) | 28.5 (11.4) | 86% White; 14% Latinx | 71% heterosexual; 29% lesbian, gay, bisexual, or queer | 44% working class; 44% middle class; 12% upper middle class (self‐report) | n/a | Cross‐sectional | ED examination; pandemic‐related stress | Pandemic‐related stress associated with ED symptoms and perceived weight gain (>LGBTQ+ individuals) | 2 |

| Taquet et al. (2021) | United States | 5,186,451 (55%) | 15.4 (9.0) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Patients with any ED diagnosis | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Incidence of ED diagnosis | Diagnostic incidence of EDs 15.3% higher in 2020 compared with previous 3 years; increase occurred solely in women, and primarily related to teenagers and AN; higher proportion of patients with EDs in 2020 had suicidal ideation or attempted suicide | 1 |

| Termorshuizen et al. (2020) | United States; Netherlands | United States/Netherland: 511/510 (gender identity: 95/98% women; 2/0.6% nonbinary/genderfluid/“other”) | United States: 30.6 (9.4); Netherlands: 90% 16–39 years | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 665; BN n = 295; BED n = 216; AAN n = 203; OSFED n = 192; purging disorder n = 47; ARFID n = 36; night‐eating syndrome n = 25 | Cross‐sectional | Impact of COVID on EDs, general physical and mental well‐being, and ED treatment | Participants with AN reported increased restriction and fears about being able to find foods consistent with meal plan from pre‐ to during COVID; participants with BN and BED reported increases in binge eating and urges to binge; participants reported positive effects of COVID including greater connection with family, more time for self‐care, and motivation to recover | 2 |

| Trott et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 319 (84%) | 36.7 (11.8) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Longitudinal | Body dysmorphic symptoms; eating attitudes; exercise addiction | ED symptomatology and exercise increased while exercise addiction decreased from pre to postlockdown; no changes in body dysmorphic symptoms from pre‐ to postlockdown | 2 |

| Vall‐Roqué et al. (2021) | Spain | 2601 (gender: 100% women) | 24.1 (5.0) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | ED inventory; social network sites use; self‐esteem | Social media network site use increased from pre‐ to during lockdown and was associated with lower self‐esteem (g = 0.15 for 14–24 year olds), higher body dissatisfaction (g = −0.14 for 14–24 year olds), and higher drive for thinness (g = −0.18 for 14–24 year olds, g = −0.22 for 25–35 year olds) (>younger age) | 2 |

| Vitagliano et al. (2021) | United States | 89 (sex assigned at birth: 89% female) | 18.9 (2.9) | 78% White, non‐Hispanic; 8% Asian; 7% Multiracial; 4% Hispanic; 1% Black; 2% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | 84% restrictive ED diagnosis; 16% other ED diagnosis | Cross‐sectional | ED related concerns and motivation to recover; triggering environment; ED diagnosis | 63% reported concern for worsening of their ED due to a “triggering environment”; 74% reported an increase in ED thoughts, 77% reported anxiety, 73% reported depression, and 80% reported isolation they perceived to be related to COVID; 29% reported decrease in motivation to recover they perceived to be related to COVID; participants who reported concern for worsening of their ED due to a triggering environment expressed decreased motivation to recover (OR = 18.1) and increased ED thoughts (OR = 23.8) compared to those who did not report concern for worsening of their ED due to a triggering environment | 3 |

| Vuillier et al. (2021) b | United Kingdom | 207 (63%) | 30.0 (9.7) | 93.7% White British/Irish/Scottish/European; 5.3% Asian; 0.5% Black; 0.5% Arab | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 91; BN n = 46; BED n = 44; OSFED n = 26 | Cross‐sectional | Depression, anxiety, stress; ED examination | 83.1% reported worsening of ED symptomatology, 7.7% reported no change, 6.8% reported improvements in ED symptomatology; changes did not differ based on diagnosis; changes to routine and physical activity and emotion difficulties were most important factors in predicting change in ED symptoms | 3 |

| White III (2021) | United States | 311 (70%) | Not reported | 33.1% African American; 55.3% White; 11.6% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cross‐sectional (retrospective) | Physical activity; self‐esteem; BI | Self‐esteem and BI worsened from pre‐ to during COVID | 3 |

| Zhou and Wade (2021) | Australia | 100 (100%) | 19.9 (2.0) | 88% White; 6% Asian; 6% “other” | Not reported | Not reported | n/a | Cohort (part of randomized controlled trial) | ED examination; BI acceptance; self‐compassion | Weight concerns (d = 0.46), DE (fasting, binge eating, vomiting, and driven exercise; d = 0.55), and negative affect (d = 0.40) increased from pre‐ to during COVID, all associated with moderate effect sizes | 2 |

Note: Study quality was assessed using the EPHPP guidelines as follows: 1 = “strong,” 2 = “moderate,” 3 = “weak.” Effect size interpretation: Cohen's d/Hedge's g: 0.2 = small, 0.5 = medium, 0.8 = large; η 2/η 2 p: 0.01 = small, 0.06 = medium, 0.14 = large; r 2: 0.01 = small, 0.09 = medium, 0.25 = large; odds ratio (OR): 1.68 = small, 3.47 = medium, 6.71 = large c ; Pearson's r: 0.1 = small, 0.3 = medium, 0.5 = large.

Abbreviations: AN, anorexia nervosa; AAN, atypical anorexia; AN‐BP, binging/purging anorexia subtype; AN‐R, restrictive anorexia subtype; ARFID, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder; BED, binge eating disorder; BI, body image; BN, bulimia nervosa; DE, disordered eating; ED, eating disorder; OSFED, other specified feeding or eating disorder; UFED, unspecified feeding or eating disorder.

The majority of included studies did not specify whether they assessed sex assigned at birth, gender, or gender identity; where this information is available, sex assigned at birth, gender, and gender identity are reported separately.

Signifies a multimethods paper. Information detailed here concerns the quantitative methods, analysis, and findings. See Table 2 for the qualitative characteristics of this study.

Chen, H., Cohen, P., & Chen, S. (2010). How big is a big odds ratio? Interpreting the magnitudes of odds ratios in epidemiological studies. Communications in Statistics—Simulation and Computation, 39(4), 860–864.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of qualitative studies

| Author(s) (year) | Country | Participants | Methodology | Key findings | Study quality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (% female) a | Age M (SD) | Race and ethnicity | Sexual orientation | Socioeconomic status | Diagnosis | Data collection methods | Data analysis | ||||

| Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2020) b | United Kingdom | 129 (94%) | 29.3 (89.0) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 62% current ED/relapse; in recovery 6.2% <3 m, 6.2% 3–12 m, 25.6% >12 m | Online survey | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) disruption to living situation; (2) increased social isolation and reduced access to usual support networks; (3) changes to physical activity rates; (4) reduced access to healthcare services; (5) disruption to routine and perceived control; (6) increased exposure to triggering messages; (7) changes to the individual's relationship with food; (8) positive outcomes | 6.5 |

| Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2021) b | United Kingdom | 58 (98%) | 30.9 (11.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 63.8% current ED/relapse; 36.2% in recovery; AN n = 28; BN n = 7; OSFED n = 3; BED n = 2; symptoms of multiple EDs n = 12; undisclosed ED n = 7 | Online survey | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) ED behaviors as an ‘auxiliary control mechanism’; (2) loss of auxiliary control after lockdown | 6.5 |

| Brown et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 10 (90% women; 10% nonbinary) | 29.5 (5.0) | 100% White | Not reported | Not reported | OSFED n = 2; AN n = 6; BED n = 1; “other” n = 1 | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) social restrictions; (2) functional restrictions; and (3) restrictions in access to mental health services | 10 |

| Buckley et al. (2021) b | Multiple | 204 (86%) | 27.0 (8.1) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 10.7% current ED diagnosis; 32.8% previous ED diagnosis (AN n = 29; BN n = 11; ON n = 9; BED n = 7; “other” n = 11) | Online survey | Content analysis | Content analysis highlighted worsened BI, worsened relationship with food, and additional COVID challenges; DE occurred predominantly in the form of binge eating, body preoccupation, fear of body composition changes, and inhibitory food control | 7.5 |

| Clark Bryan et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | 21 (86%) | 25.5 (5.6) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) reduced access to ED services; (2) disruption to routine and activities in the community; (3) heightened psychological distress and ED symptoms; and (4) increased attempts at self‐management in recovery | 6 |

| Fernández‐Aranda, Casas, et al. (2020) Study 2 | Spain | 8 (not reported) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN | Text‐based focus group | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) connecting in isolation; (2) helping others versus helping oneself; (3) challenges of reduced professional support; (4) balancing the needs of the individual within the family | 3 |

| Frayn et al. (2021) | United States | 11 (64% women; 9% transmen) | 42.8 (14.2) | 81.8% White; 18.2% Black | Not reported | Household annual income (USD): 9.1% 0–10,000; 9.1% 25,001–30,000; 9.1% 30,001–35,000; 9.1% 45,001–50,000; 9.1% 70,001–75,000; 45.5% 100,000+ | BED n = 7; BN n = 2; OSFED n = 2 | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) variability in improvement or exacerbation of symptoms due to COVID; (2) changes in the physical environment were associated with symptom improvement; (3) social implications of COVID associated with both symptom improvement and deterioration; (4) greater overall stress/anxiety levels led to more binge episodes | 7.5 |

| Hunter and Gibson et al. (2021) | United States; Greece; United Kingdom | 12 (92%) | 31.8 (not reported) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 10; AN and BN n = 1; BN n = 1 | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) loss of control; (2) support during confinement; (3) time of reflection on recovery | 8 |

| McCombie et al. (2020) | United Kingdom | 32 (94%) | 35.2 (10.3) | 100% White | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 23; BN n = 3; BED n = 1; “other” n = 5 | Online survey | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) mechanisms contributing to ED exacerbation; (2) positive aspects of lockdown | 7.5 |

| Nutley et al. (2021) | Multiple | 305 social media posts | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Subreddit posts (r/EatingDisorders, r/AnorexiaNervosa, r/BingeEatingDisorder | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) change in ED symptoms; (2) change in exercise routine; (3) impact of quarantine on daily life; (4) emotional well‐being; (5) help‐seeking behavior; (6) associated risks and health outcomes | 7.5 |

| Quathamer and Joy (2021) | Canada | Survey: 70 (gender: 45% women; 22% agendered, nonbinary, genderfluid, or gender vague; 9% transgender); interview: 8 (gender: 50% ciswomen; 12.5% transwomen; 25% nonbinary) | Not reported | Survey: 81% White; 9% Indigenous; 6% Latinx; 3% Asian; 1% Middle Eastern; interview: 87.5% White; 12.5% South Asian | Survey: 27% gay; 23% bisexual; 17% lesbian; 12% queer; 6% pansexual; 3% 2‐spirit; 3% demisexual; 1% nonfixed; 1% questioning; interview: 12.5% gay; 25% lesbian; 25% bisexual; 12.5% queer; 12.5% asexual; 12.5% nonspecified | Not reported | n/a | Online survey and semi‐structured interviews | Foucauldian discourse analysis | Discursive considerations generated: (1) time for reflection; (2) time away from social surveillance; (3) time to work on oneself; and (4) time to (dis)connect; woven through these considerations were social discourses of hetero‐cis‐normativity, healthism, and resistance | 10 |

| Richardson et al. (2020) b | Canada | 56 chat transcripts | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Textual analysis of chat transcripts | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) lack of access to treatment; (2) worsening of symptoms; (3) feeling out of control; (4) need for support | 8 |

| Simone et al. (2021) | United States | 510 (not reported) | 24.7 (2.0) | 29.6% White; 23.9% Asian; 16.5% Latino/Hispanic; 18.2% African American/Black; 11.8% mixed/“other” | Not reported | 32.7% low; 20.7% low‐middle; 17.0% middle; 18.5% upper‐middle; 11.2% high (parental socioeconomic status primarily based on baseline educational attainment) | n/a | Online survey | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) mindless eating and snacking; (2) increased food consumption; (3) generalized decrease in appetite or dietary intake; (4) eating to cope; (5) pandemic‐related reductions in dietary intake; (6) re‐emergence or marked increase in ED symptoms | 8 |

| Stoddard (2021) b | United States | 17 (gender identity: 100% women) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Semi‐structured interviews and autoethnography | Content analysis | Themes generated: (1) influencing factors for BI disturbance/EDs during COVID (stress and distress; social isolation; time; activity level changes; media; control; external situations; other mental health issues; weight change); (2) coping mechanisms; (3) hopes and fears | 9.5 |

| Tabler et al. (2021) b | United States | 43 (63% ciswomen; 2% transwomen; 7% nonbinary; 5% queer) | 27.7 (9.2) | 79% White; 7% biracial/multiracial; 12% Latinx/Hispanic; 2% Asian American | 19% lesbian; 16% gay; 35% bisexual; 7% queer; 12% pansexual; 5% asexual; 7% expansive sexuality/unlabeled | 44% working class; 44% middle class; 12% upper middle class (self‐report) | n/a | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) physical activity constraints; (2) eating patterns; (3) weight concerns | 7 |

| Vuillier et al. (2021) b | United Kingdom | 207 (63%) | 30.0 (9.7) | 93.7% White British/Irish/Scottish/European; 5.3% Asian; 0.5% Black; 0.5% Arab | Not reported | Not reported | AN n = 91; BN n = 46; BED n = 44; OSFED n = 26 | Online survey | Thematic Analysis | Themes generated regarding impact of COVID: (1) difficult emotions; (2) changes to routine; (3) confinement; (4) unhelpful social messages—making a transformation; (5) emotional support from others; (6) emotion coping skills; (7) accessibility—barriers and facilitators; (8) loss of support | 7 |

| Zeiler et al. (2021) | Austria | 13 (100%) | 15.9 (1.4) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | AN‐R n = 9; AN‐BP n = 4 | Semi‐structured interviews | Thematic analysis | Themes generated: (1) restrictions of personal freedom; (2) interruption of treatment routine; (3) changes in psychopathology; (4) opportunities of COVID period | 7.5 |

Note: Study quality was assessed using an adapted version of the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) tool (Long et al., 2020).

Abbreviations: AAN, atypical anorexia; AN, anorexia nervosa; AN‐BP, binging/purging anorexia subtype; AN‐R, restrictive anorexia subtype; ARFID, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder; BED, binge eating disorder; BI, body image; BN, bulimia nervosa; DE, disordered eating; ED, eating disorder; OSFED, other specified feeding or eating disorder; UFED, unspecified feeding or eating disorder.

The majority of included studies did not specify whether they assessed sex assigned at birth, gender, or gender identity; where this information is available, sex assigned at birth, gender, and gender identity are reported separately.

Signifies a multimethods paper. Information detailed here concerns the qualitative methods, analysis, and findings. See Table 1 for the quantitative characteristics of this study.

2.5. Synthesis of results

Due to the inclusion of mixed‐methods studies and the heterogeneity of existing evidence, we adopted a narrative synthesis approach informed by the guidance by Popay et al. (2006): (1) developing a theory; (2) developing a preliminary synthesis; (3) exploring relationships in the data; and (4) assessing robustness of the synthesis.

2.5.1. Stage 1: Development of theory

This stage was performed early on in the review process and helped shape the review aims. Through an initial review of the literature and discussion among the research team, we identified several possible mechanisms whereby the COVID‐19 pandemic and related factors may influence BI, DE, and EDs, such as psychological distress due to the ongoing pandemic, disruption of access to support and treatment, food shortage and insecurity, and increased loneliness and social isolation. Key findings from the literature review are outlined in the introduction section of this manuscript. This process also highlighted a lack of studies focusing on individuals from marginalized and underrepresented populations, which we included as a key aim of our review.

2.5.2. Stage 2: Development of the preliminary synthesis

The second stage involved organizing and describing the included papers to explore patterns across studies. We followed Stern et al.'s (2020) guidance on conducting mixed‐studies systematic reviews, as outlined in the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) manual for evidence synthesis. Accordingly, we conducted the current review using the convergent integrated approach (Hong et al., 2017), whereby findings from the qualitative, quantitative, and mixed‐methods studies were integrated in the narrative synthesis. Quantitative data were transformed (or qualitized) into “textual descriptions” and presented in conjunction with qualitative data. This approach is recommended over its counterpart where qualitative data are assigned numerical values (quantitized), as codifying quantitative data is less error‐prone than attributing numerical values to qualitative data. One of the distinguishing features of mixed‐studies systematic reviews is the inclusion of primary mixed‐methods studies, from which data are extracted so they can be classified as quantitative or qualitative (Stern et al., 2020). Therefore, quantitative data from mixed‐methods studies were also transformed and synthesized with quantitative data from quantitative studies and nontransformed qualitative data from qualitative and mixed‐methods studies. Due to the variability in the emerging literature and the need to comprehensively capture all relevant findings, the themes and resulting narrative synthesis were based on a comprehensive examination of all included papers, regardless of study quality.

2.5.3. Stage 3: Exploring the relationships within and between studies

In this stage, four main themes (and two subthemes) were generated from the integrated qualitative and transformed quantitative data to answer the key research aims. The themes were generated using deductive, or theory‐driven approaches (i.e., considering data relevant to answering the review questions) and inductive, or data‐driven approaches (i.e., being open to the data that are present across studies and unexpected findings; Clarke & Braun, 2014). All themes were informed by both qualitative and quantitative research. For clarity, a selection of references is provided in the narrative synthesis; please see Tables 1 and 2 for a detailed breakdown of study findings and associated citations. Illustrative quotes for each theme are presented in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Participant quotes

| Theme | Quote | Author | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Disruptions due to COVID‐19 | “Feeling frustrated because I've been learning how to control the bulimic symptoms and normally able to manage them. Yet the change in routine (or lack of) and general stress/anxiety is unsettling it and I noticed my thoughts and behaviors changing” (participant details not provided) | Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2020) | |

| “Without structure and focus (and meaning) of uni [university] and friends and having a life that feels worth living, now it's just old habits and misery” (participant details not provided) | McCombie et al. (2020) | ||

| “My routine has gotten lost, which tampers with my sleep, which in turn tampers with my ability to follow my meal plan” (30, female participant, anorexia nervosa) | Hunter and Gibson (2021) | ||

| “For me, it was like, I go to my therapist, I leave my problems there, I go home. […] Now, many things take place in my room, and I have all these problems, these conversations right on the spot. This felt strange for me at the beginning” (participant details not provided) |

Zeiler et al. (2021) |

||

| 2. Variability in the improvement or exacerbation of symptoms | 2.1 Negative outcomes of the COVID‐19 pandemic | “I have been in recovery from AN [anorexia nervosa] and BN [bulimia nervosa] for about 2 years now, and ever since this whole isolation thing started, my symptoms have come back, and worsened almost immediately” (participant details not provided) | Richardson et al. (2020) |

| “The pandemic has increased my self‐harm, as I've felt so restricted by the government in terms of what I can do to deal with my feelings (i.e., initially – only exercise once a day, not able to exercise with anyone else). Using healthy means to deal with difficult feelings (i.e., go for a walk, meet a friend for coffee) have been more limited and so it is really easy to go back to unhelpful ways of coping such as self‐harm” (female participant, anorexia nervosa) | Vuillier et al. (2021) | ||

| “My ED feels more valuable to me than ever. It is the only constant in what feels like a completely upside down and scary world, it is my only locus of control” (participant details not provided) | Branley‐Bell and Talbot (2021) | ||

| “With the recent quarantine, I am unable to work out the same… just running and doing as much as I can. I've found my body changing in ways I am very uncomfortable with. I'm waking up daily weighing myself, logging my food, and checking my Fitbit constantly. I recently started staring in the mirror more and despising the person who looks back” (participant details not provided) | Nutley et al. (2021) | ||

| “Times when I would normally kind of be doing something potentially social or something like that over the weekend… Obviously with more free time, I might have gone back to see my parents–that […] feeling, of like, existential loneliness felt incredibly desperate and really quite painful. But it was… It came in bursts to begin with, and I think as lockdown has gone on, it's that feeling of real painful loneliness” (25, female participant, White, anorexia nervosa) | Brown et al. (2021) | ||

| “Everything is dramatically worse because of being home all the time. I have constant access to all of my food and my scale and everything to evaluate where I'm at and to facilitate eating” (participant details not provided) | Frayn et al. (2021) | ||

| “I definitely walk past the mirror more often and do some body checking” (participant details not provided) | McCombie et al. (2020) | ||