Abstract

Poliomyelitis is a crippling viral disease caused by poliovirus, a positive‐stranded RNA virus that is a serotype of Enterovirus C. Pakistan remains one of the countries in the world where poliomyelitis is still prevalent, posing an obstacle to global poliomyelitis eradication. With the commencement of the COVID‐19 pandemic, polio eradication campaigns have proven less feasible, resulting in an increase in polio cases across the country. Pakistan's healthcare system and socio‐economic framework are incapable of dealing with two deadly viruses at the same time. As a result, effective measures for combating the destruction caused by the spread of the poliovirus are required.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Pakistan, polio, public health crises

Highlights

Pakistan remains one of the nations in the world where poliomyelitis is still prevalent.

The number of polio cases in Pakistan has increased due to the disruption in vaccination procedures caused by the COVID‐19‐induced lockdown.

Aside from Polio, the COVID‐19 pandemic has resulted in an increase in the number of other infectious diseases.

The country still has the potential to eradicate polio from its soil if effective tactics, mass awareness, and public compliance are implemented.

1. INTRODUCTION

Poliomyelitis is a debilitating, viral disease caused by poliovirus that is a positive‐stranded RNA virus, a serotype of species Enterovirus C. faecal‐oral route causes person‐to‐person transmission of the virus. In 0.5% of cases, it attacks the central nervous system that causes muscle weakness leading to flaccid paralysis. 1

Along with Afghanistan, Pakistan remains one of the only two nations in the world where poliomyelitis is still prevalent, posing a barrier to the worldwide eradication of the virus. 2 Polio was on the verge of being eradicated in Pakistan, with just 12 recorded cases in 2018, however, a significant resurgence with 219 cases was reported in 2020. 3

Pakistan's healthcare authorities are presently undertaking strong efforts to prevent the spread of wild poliovirus type 1 and vaccine‐derived poliovirus type 2. To reach this goal, healthcare services are focussing on preventing virus transmission through coordinated efforts at national and international borders, as well as through the implementation of quality immunisation programs. 4

Alongside polio, Pakistan's battle against the COVID‐19 pandemic, that started in early 2020, is still ongoing. As of the 30th of January 2022, the overall number of confirmed cases had risen to 1.42 million, with about 29,269 deaths as a result of covid. 5 Although, these numbers are far better in comparison with not only countries of South Asia, but also the developed nations of the West, collective efforts by the State and the people are still needed to overcome this crisis. In this context, it is noteworthy that Pakistan has so far delivered at least 174,085,175 doses of COVID vaccination. Assuming that each individual requires two doses, that would be enough to vaccinate around 40% of the country's population. 6

A number of other infectious illnesses have also been on the rise as a result of the COVID‐19 pandemic. A large upsurge in the cases of dengue virus is reported in Pakistan. 7 This is mainly because COVID‐19 control measures have disrupted dengue vector control programs throughout the country by restricting their entry into homes. 10 Similarly, mucormycosis cases have also increased significantly in Pakistan. 8 , 9 It is believed that post COVID‐19 infection, individuals develop a weakened immune system leading to increased vulnerability to the fungal disease thereby increasing its spread. 9

However, the onset of the COVID‐19 Pandemic in Pakistan after February 2020, a nationwide lockdown has been imposed in order to restrict COVID‐19 transmission. Because of the disturbance in the vaccination procedure caused by the coronavirus‐induced lockdown, the number of polio cases in Pakistan has increased. 11 The epidemic and subsequent lockdown jeopardised the success of polio immunisation programs, making it harder to contact poliovirus‐infected persons, resulting in an increase in the number of poliovirus cases. The disruptions caused by the imposition of a sudden lockdown hampered the identification of suspected polio virus propagation and cases, resulting in a significant under‐reporting of the real number of cases of the deadly illness. As a result, COVID‐induced lockdowns are the primary cause of the significant spike in polio cases in a short period of time. The authors outline the state's response to probable polio transmission during the COVID‐19 outbreak, discuss the issues and consequences, and provide evidence‐based recommendations based on these concerns.

2. BURDEN AND CURRENT STATUS OF POLIO AMIDST COVID‐19 IN PAKISTAN

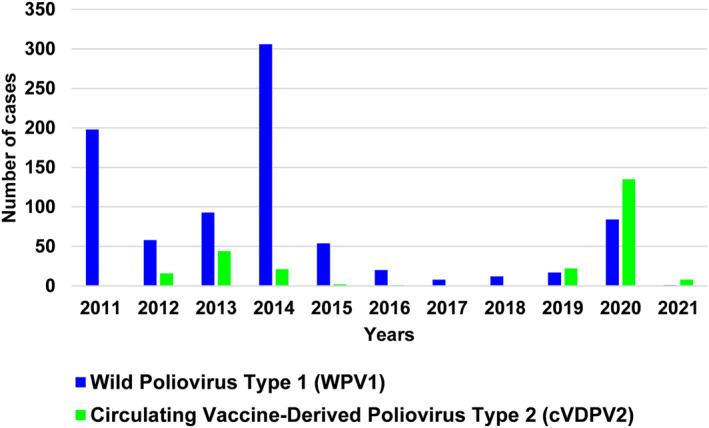

Poliomyelitis has been endemic in Pakistan since the 1970s, with outbreaks recorded from various parts of the nation to date. Recently, however, the country witnessed a significant rise in the number of polio cases in 2020 (Figure 1). One particular reason that is widely implicated to be the cause of this sudden rise is the imposition of strict lockdowns across all cities of Pakistan that were set in place in order to limit the spread of COVID‐19. Albeit successful in flattening the curve, these intermittent lockdowns lead to a temporary suspension of the polio vaccine campaigns, causing outbreaks in several parts of the country. 12 Upon comparing data on child polio immunisation before lockdown (23 September 2019–22 March 2020) to the first 6 weeks of lockdown (March 23–9 May 2020), it was observed that the mean number of daily immunisation visits decreased by 52.8%. Hence, on average, 2734 children per day missed routine immunisation during the lockdown. 12

FIGURE 1.

Current situation of polio cases in Pakistan from 2011 till August 2021

In the early 2021, however, Pakistan eased several lockdown restrictions and as a result vaccination campaigns resumed. This was reflected by a decrease in polio cases reported until August 2021. Further data collection and surveillance of new polio cases is ongoing, and no official reports have been published since.

Both COVID‐19 and polio differ significantly in multiple aspects, however, being infectious diseases, they do share some common ground (Table 1). Like polio, the COVID‐19 pandemic has been a burden on world's economies, and has led to an economic turmoil worldwide. In addition to this, the magnitude of fear, trauma, and mental distress brought about by both of these diseases has been equally devastating for the world.

TABLE 1.

Summary of general features of Poliomyelitis and COVID‐19

| Features | Poliomyelitis | COVID‐19 |

|---|---|---|

| Mode of transmission | Faecal‐oral (most common) and less commonly by respiratory droplets | Person to person through respiratory droplets, airborne |

| Incubation period | 3–6 days for onset of infection and 7–21 days for developments of paralysis | Somewhere between 2 and 14 days after exposure |

| Clinical presentation | Mostly asymptomatic, some may have non‐specific symptoms like fever, sore‐throat, malaise | Typically presents with shortness of breath, cough, fatigue, fever; sometimes asymptomatic |

| Risk groups | Children <5 years, unvaccinated individuals, immunocompromised patients, pregnant women | Older people, immunocompromised individuals, patients with underlying medical problems like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, and cancer |

| Diagnosis | Culture via throat secretions, stool specimen, CSF | RT‐PCR |

| Treatment |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| Prevention | Inactivated (killed) polio vaccine (IPV), live attenuated (weakened) oral polio vaccine (OPV) | Nucleic acid vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer/BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccines), viral vector vaccines (Oxford/AstraZeneca, Janssen, CanSino) |

3. RECOMMENDATIONS

Leaders from all over the world have praised Pakistan's efforts to combat the COVID‐19 outbreak. 13 With this accomplishment in mind, the prospect of a polio‐free Pakistan does not seem that far‐fetched. To do this, an integrated approach similar to that used to combat COVID‐19 infection is necessary.

Knowing that lockdowns are a huge obstacle in the way of effective polio vaccination drives, flattening the curve of COVID‐19 cases becomes highly essential in order for polio immunisation campaigns to resume function. For this, Standard Operating Procedures issued by the State, in accordance with world health organization, such as wearing masks, avoiding large social gatherings, and maintaining a 6 ft. Distance among people in public settings etc., should be strictly implemented. At national level, policy makers should ensure the provision of COVID‐19 vaccines to all parts of the country, free of cost. Healthcare providers, and frontline health‐workers should be provided with Personal Protective Equipment like masks, surgical gowns, and face shields etc. To prevent depletion of medical workforce. The State should also make stringent disease surveillance policies to accurately monitor epidemiological data of infectious disease cases endemic in Pakistan, so that legislators are better‐equipped for making management strategies. Furthermore, State‐sponsored research should be routinely carried out to identify the challenges leading to outbreaks, and suggest effective measures accordingly.

Moreover, it should be noted that factors such as cultural and religious barriers against polio vaccines, lack of awareness among masses regarding disease spread and good hygiene practices continue to be constant obstacles in eradication of polio from Pakistan. 14 To combat these, regular educational campaigns need to be conducted in high‐risk areas. Media should play its part in spreading awareness, and work in collaboration with healthcare authorities to impart accurate information, and bust myths and misconceptions surrounding polio vaccines. Additionally, security should be provided to vaccine campaigners going to militant occupied areas of Pakistan to ensure proper and effective reach.

4. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it can rightly be established that the emergence of COVID‐19 has affected Pakistan's struggle against polio. However, with effective strategies, mass awareness, and public compliance, the country still stands a chance in achieving complete eradication of polio from its land.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The formal ethical clearance was not applicable for this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

All authors have substantially contributed in this research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None. No external funding was used in this study.

Sahito AM, Saleem A, Javed SO, Farooq M, Ullah I, Hasan MM. Polio amidst COVID‐19 in Pakistan: ongoing efforts, challenges, and recommendations. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2022;37(4):1907‐1911. 10.1002/hpm.3466

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1. CDC. Poliomyelitis. Accessed September 21, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/polio.html [Google Scholar]

- 2. Yusufzai A. Efforts to eradicate polio virus in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Lancet Child Adolesc Heal. 2020;4(1):17. 10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30382-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polio Cases Update 2020 | across Pakistan’s Provinces. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.endpolio.com.pk/polioin‐pakistan/polio‐cases‐in‐provinces [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pakistan polio eradication programme | end polio Pakistan. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.endpolio.com.pk/

- 5. Worldometer. Pakistan COVID ‐ coronavirus statistics. Published 2022. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/pakistan/

- 6. Pakistan: the latest coronavirus counts, charts and maps. Published 2022. Accessed January 31, 2022. https://graphics.reuters.com/world‐coronavirus‐tracker‐and‐maps/countries‐and‐territories/pakistan/

- 7. Yousaf A, Khan FMA, Hasan MM, Ullah I, Bardhan M. Dengue, measles, and COVID‐19: a threefold challenge to public health security in Pakistan. Ethics, Med Public Heal. 2021;19:100704. 10.1016/J.JEMEP.2021.100704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Asri S, Akram MR, Hasan MM, et al. The risk of cutaneous mucormycosis associated with COVID‐19: a perspective from Pakistan. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2021;37:1157‐1159. 10.1002/HPM.3311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ghazi BK, Rackimuthu S, Wara UU, et al. Rampant increase in cases of mucormycosis in India and Pakistan: a serious cause for concern during the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;1,1144‐1147(aop). 10.4269/AJTMH.21-0608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cavany SM, España G, Vazquez‐Prokopec GM, Scott TW, Alex Perkins T. Pandemic‐associated mobility restrictions could cause increases in dengue virus transmission. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15(8):e0009603. 10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0009603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Din M, Ali H, Khan M, et al. Impact of COVID‐19 on polio vaccination in Pakistan: a concise overview. Rev Med Virol. 2021;31(4). 10.1002/RMV.2190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chandir S, Siddiqi DA, Setayesh H, Khan AJ. Impact of COVID‐19 lockdown on routine immunisation in Karachi, Pakistan. Lancet Glob Heal. 2020;8(9):e1118‐e1120. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30290-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. DAWN.COM . WHO praises Pakistan’s handling of Covid‐19 pandemic ‐ Pakistan. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.dawn.com/news/1578971

- 14. Ahmad S, Babar MS, Ahmadi A, Essar MY, Khawaja UA, Lucero‐Prisno DE. Polio amidst COVID‐19 in Pakistan: what are the efforts being made and challenges at hand? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;104(2):446‐448. 10.4269/AJTMH.20-1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.