Abstract

Background

The health workforce is a key component of any health system and the present crisis offers a unique opportunity to better understand its specific contribution to health system resilience. The literature acknowledges the importance of the health workforce, but there is little systematic knowledge about how the health workforce matters across different countries.

Aims

We aim to analyse the adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities of the health workforce during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Europe (January‐May/June 2020), and to assess how health systems prerequisites influence these capacities.

Materials and Methods

We selected countries according to different types of health systems and pandemic burdens. The analysis is based on short, descriptive country case studies, using written secondary and primary sources and expert information.

Results and Discussion

Our analysis shows that in our countries, the health workforce drew on a wide range of capacities during the first wave of the pandemic. However, health systems prerequisites seemed to have little influence on the health workforce's specific combinations of capacities.

Conclusion

This calls for a reconceptualisation of the institutional perquisites of health system resilience to fully grasp the health workforce contribution. Here, strengthening governance emerges as key to effective health system responses to the COVID‐19 crisis, as it integrates health professions as frontline workers and collective actors.

Keywords: COVID‐19 pandemic, European comparison, health governance, health system resilience, health workforce capacities

Highlights

The health workforce contributes to health system resilience.

Comparative analysis of adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities.

Health systems prerequisites have little influence on capacity combinations.

Governance emerges as key to health system responses to the coronavirus disease‐2019 crisis.

1. INTRODUCTION

The health workforce is a key component of any health system. Nurses, care assistants, medical laboratory technicians, doctors and many more health workers deliver services, which together help to realise the basic right of citizens to health care. This has led the World Health Organisation (WHO) to the categorical statement that there is no ‘No health without a health workforce’. 1 This is even more true in times of crises like the present coronavirus disease‐2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic. The health workforce emerges as a fundamental part of how health systems have responded to the multiple and significant challenges posed by the Covid‐19 pandemic. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12

Current policy debates reflect this. For example, the European Commission, stresses that 21 out 28 Member States need to improve their health workforce, 13 similarly WHO Regional Office Europe 14 and a newly established Pan European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development Goals urged European health leaders to take action against understaffing and underfinancing of the health workforce. 15 In collaboration with the WHO and the European Observatory, the European Union (EU) has also set up the COVID‐19 Health Systems Response Monitor, which provides information and tools on how to expand the health workforce during the pandemic. 16 , 17 , 18 Most recently, an EU Expert Panel 4 developed policy recommendations on the resilience of health and social care services, which included strengthening workforce training and resilience and fostering collaboration across different professions and sectors.

In the debate of how health systems have responded to the Covid‐19 pandemic, there has been considerable interest in the concept of health system resilience. In general terms, this describes the ability to prepare, manage, recover and learn from a crisis like the COVID‐19 pandemic and better handling any similar crisis in the future. 10 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 This includes two types of capacities: reactive capacities to absorb, survive and reorganise following acute instability; and proactive capacities to anticipate and prepare for relevant sources of instability. 23

The literature on health system resilience acknowledges the importance of the health workforce. 4 , 24 , 25 For example, Chamberland‐Rowe et al. 23 identify the health workforce as one of the building blocks of the health system, which form a prerequisite for health systems resilience. Hanefeld and colleagues 25 go one step further and argue the health workforce is one of three components of health system resilience, that is, besides health information systems and funding/financing mechanisms.

However, we continue to have little systematic, cross‐country comparative knowledge about how the health workforce matters for health system resilience across different countries. The present crisis offers a unique opportunity to better understanding the specific contribution of the health workforce to health system resilience, and, more specifically, the adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities of the health workforce, and how these differ across health systems. 4 , 9 , 26 The initial picture emerging from ongoing public health debates in Europe is that there are many examples of very quick up‐skilling, an exceptionally high level of flexibility and very well developed ability to adapt to new demands, for example. 11 , 16 , 18 , 27 , 28

At the same time, there is growing awareness of mental health needs and well‐being of the health workforce, including the importance of appropriate personal protection equipment. 11 The WHO Regional Director for Europe reminds us that: ‘We have no COVID‐19 response if we do not care for our health‐care and essential workers: their needs and well‐being must be prioritized’. 29 The pandemic has reinforced a need to pay greater attention to both, the resources of the health workforce and the ‘human face’ of the health workforce. 8 , 12 , 26 , 30

Currently, we continue to have little (if any) systematic knowledge about how the various new challenges the COVID‐19 pandemic has been posing for health systems connect not only the health system resilience but also the role of the health workforce in these transformations.

1.1. Aim and scope

Against this background, the aim is to study health system resilience with a focus on the health workforce. More specifically, we analyse the adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities of the health workforce during the first wave of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Europe (January until about May/June 2020, although peaks may vary regionally), and we assess how these capacities differ across countries. We adopt a cross‐country comparative perspective to assess how health systems influence the contribution of the health workforce. The study is based on a comparison of selected health policy and health services responses in six health systems in Europe, incorporating different types of systems (i.e. national health systems and social health insurance systems) and severity of the crisis (i.e. mortality rates) during the first wave of the pandemic.

2. METHODS AND MATERIAL

We focus on health system resilience specifically in relation to the health workforce, namely on activities of health workforce planning, training and organisation. Here, we consider the health workforce across different parts of the health system: hospital and primary care services, old age care services and mental health services as well as public health services. Firstly, in terms of planning, the pandemic has made immediate and high demands on the health workforce and has pushed for its expansion. Examples of planning activities are recruitment of retired health personnel as well as medical and nursing students, and setting up job banks for volunteers with healthcare qualifications. 18

Secondly, concerning training, the pandemic has highlighted the need for strengthening particular, specialist skills in the health workforce. This has included a variety of measures, such as training nurses in basic respiratory/pulmonary care, re‐skilling retired doctors and up‐skilling medical students. Thirdly, in terms of organisation, the pandemic has made considerable demands on rapid changes of the organisation of hospital and primary care services as well as public health, long‐term care and mental healthcare services. This is not only to deal with patients with Covid‐19, but also to free‐up resources in other health services and comply with new regulations to contain the pandemic. 18 , 31

2.1. Theoretical approach

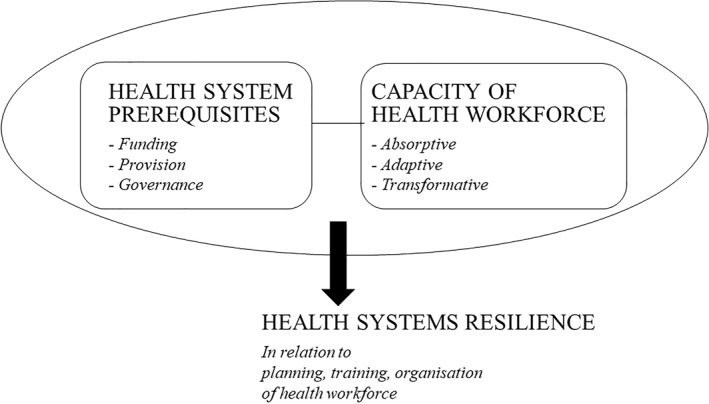

Theoretically, we draw on the literature on health workforce research, studies of professions and comparative studies of health systems, governance and policy 2 , 10 , 32 , 33 , 34 in addition to the literature on health system resilience. 4 , 23 , 25 , 35 , 36 Figure 1 below gives an overview of our analytical framework.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of analytical framework. Source: authors’ own figure, adapted and transformed from 35

We identify different ways in which the health workforce contributes to health system resilience by drawing on the distinction between three types of capacities for health system resilience, 24 , 37 which can exist at micro‐, meso‐ and macro levels. 23 Absorptive capacity refers to the ability to maintain existing levels of services in terms of quantity and quality, using the same level of resources and capacities, for example existing hospital staff moving to other departments to keep workforce capacity stable. In contrast, adaptive capacity concerns the ability and willingness of the health workforce to accommodate change by using new sets of resources, for example medical students and volunteers joining the existing workforce to fill in the gaps. The degree of novelty is even greater in relation to transformative capacity, as in the ability of the health workforce to respond to changing environments through making fundamental changes to the function and structures of health systems, for example pharmacists taking over tasks of doctors to increase COVID‐19 vaccination capacity.

The three sets of capacities are operationalised in different ways, including directly connected strategies (e.g. health workers moving to Covid‐19 wards) and indirectly connected strategies (e.g. formalisation of e‐consultations).

We focus on the health system as the central prerequisite of health system resilience and the specific capacities of the health workforce. 4 , 23 We distinguish between funding, provision and governance. 32 Each set of health systems prerequisite includes specific aspects related to health services and the health workforce, which we expect support absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacity of the health workforce to contribute to health system resilience. 4 , 10 , 25 , 37 For an overview of health systems prerequisites see Table 1 below.

TABLE 1.

Overview of health systems prerequisites

| (1) FUNDING |

|

| |

| (2) PROVISION |

|

| |

| (3) GOVERNANCE |

|

|

Concerning funding, the literature on health system resilience suggests, this is especially a question of the relative stability of funding. Overall, public funding from taxes and/or social insurance contributions offers considerable stability. However, this can vary across countries, depending on the earmarking of funding together with the more general political priorities and economic resources of individual countries. Funding also needs to be flexible in order to be able to accommodate the shifting priorities in times of health crises. This includes the possibility of shifting funding between sectors and of allocating additional resources. 38

The dimension of provision relates to both the organisation of health services and the organisation of the health workforce. 39 The relative mix of public, non‐profit and for‐profit provision gives an indication of the relative organisational complexity (and possible fragmentation) of health services. Health crises make more demands on coordination and here, existing levels of integration and associated flexibility can be an important resource. Similarly, adequate levels of service provision can offer buffers for higher demands in times of health crises. The same applies to the health workforce. It is easier to absorb sudden surges in demands when there is sufficient staff who are flexible because of high levels of training and who are used to working across professional and service boundaries. 18 It is also easier if solidarity and civil society engagement are shared values and trust and commitment are generally high. 25 , 40

The dimension of governance concerns the relative public (central) control over health services and the health workforce, and the relative integration of the health workforce in health governance. The first aspect relates to issues of governance capacity, whereas the second is about the professional ownership of health governance. Both are crucial for governing health crises in a sustainable manner. 25 Importantly, we conceptualise health professions and professionalism as a subcategory of governance that may intersect with other modes of governance, thus making governance highly flexible and transformative.

2.2. Case selection and material

We select Austria, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK for the comparative analysis. The countries have different types of healthcare systems and we expect this makes for different health systems prerequisites, which in turn influence health workforce capacities. 2 , 41 , 42 In the first wave of the pandemic, the countries are also characterised by different scales of crisis as reflected in the relative pandemic burden. Mortality offers a timely indicator and excess mortality rather than deaths allows for robust comparisons across countries. 43 , 44 Table 2 below gives an overview of the countries included for comparison.

TABLE 2.

Overview of selection of countries for comparative analysis

| NHS | Social insurance | |

|---|---|---|

| Low burden | Denmark | Germany/Austria |

| High burden | Italy/UK | Netherlands |

Abbreviation: NHS, National Health Service.

2.3. Data collection and analysis

Country experts collected the material and provided short, descriptive country case studies, using written secondary and primary sources and expert information. This formed the basis for a comparative analysis. A step‐by‐step approach was applied: the lead (first and last) authors developed a first comparative analysis of the country case material and highlighted data gaps; the country case studies were subsequently revised and amended and the comparative results discussed by all authors; the procedure was repeated until data gaps were closed and consensus was reached.

3. RESULTS

3.1. What are the capacities of the health workforce?

During the first wave of the pandemic, the health workforce drew on a broad range of capacities. The absorptive capacity of the health workforce related particularly to hospitals and to freeing up capacities for newly established Covid‐19 wards. In local hospitals, nurses in particular moved to other departments, and they went through some retraining in intensive care treatment. Measures by national governments amplified the capacity of the existing workforce. Besides the cancelation of elective surgery, several countries suspended the collective agreements about work responsibilities, and about working time and holidays (Germany, Denmark, Netherlands).

Another set of measures concerned relaxing quality standards. The approach in the Netherlands was direct; for example, the Health and Youth Care Inspectorate temporarily allowed hospital pharmacists to use prefabricated medicine. Instead of distributing medicines and corresponding fluids separately such as for antibiotics treatment, hospital pharmacists received authorisation to prepare drips to save time. 45 , 46 The approach in Denmark was more indirect, and the Danish Patient Safety Authority acknowledged COVID‐19 as a mitigating circumstance in the case of clinical errors. 47 Absorptive capacity can also be concerned with securing the sheer availability of the workforce. For example, the federal government in Austria charted special trains to ensure that care workers from Romania could return to their work despite border closures. 30 , 48 For their part, employers were responsible for paying for Covid‐19 tests and hotel quarantine in case of a positive test result. 49

In the first wave of the pandemic, the adaptive capacity of the health workforce in our countries focused on increasing health workers not least in the newly established Covid‐19 wards in hospitals. This included especially the recruitment of new staff: recent graduates, returnees to clinical practice and retirees, and foreign health workers joined the existing health workforce. In the Netherlands, for instance, this included health workers whose registration had lapsed. The Health and Youth Inspectorate allowed re‐entry into independent practice for those health workers whose registration had lapsed within the last 2 years; whereas all others had to work under supervision. 50 In Germany, health workers also moved from part‐time to full‐time employment. 27 Austria had a particular focus on increasing the number of carers and mental health workers. In relation to the former, a new labour market agreement included wage increases and some improvement of working conditions. 51

Another set of strategies related to the adaptive capacity of the health workforce was concerned with changing the organisation of healthcare. One type of change concerned the introduction of new organisational forms. Teams for intensive care of patients with Covid‐19 are a prominent example across countries. For example, in England, with routine surgery slowing in many hospitals operating theatre practitioners retrained to work in new areas. Practitioners often joined four‐person teams, working around the clock to attend Covid‐19 related intubations, cardiac arrests and trauma calls. 52 Another example of the introduction of new organisational forms was the establishment of auxiliary hospitals in Germany. For instance, the organisation of an auxiliary hospital at Hannover 53 followed national guidelines by the federal public health authority and was based on nursing‐led management; the hospitals drew on tailored training and electronic systems to support documentation and coordination.

Another type of change was the scaling‐up of existing organisational forms. For example, in Denmark, many municipalities significantly redefined and accelerated existing structures for coordination to organise the discharge of patients with Covid‐19. 54 , 55 , 56 Changing the organisation of healthcare can also involve different levels. For example, in Italy, initially, the regions drew up overall plans for re‐organising health service to respond to the emergencies created by the pandemic, which also emphasised existing differences in regional models. 57 , 58 Subsequently, there has been a greater attempt to coordinate measures between central government and the regions. However, conflicts between the two levels of government are frequent and coordination looks difficult when discussing the measures to contain the pandemic. 59 , 60 , 61

The degree of novelty was even greater in relation to the transformative capacity, understood as the ability to respond to changing environments through making fundamental changes to the function and structures of health systems. One set of changes related to new service offerings, including the introduction of new mental health services. For example, in Austria, the main social insurance significantly increased the number of therapy sessions available for reimbursement under the social insurance scheme. 62 A smaller social insurance doubled the reimbursement for therapy sessions. 63 Across countries, there was an increase in the use of remote consultations and some countries formalised this change in health services delivery (Denmark, England, Germany, Netherlands). For example, in the Netherlands, the Dutch Health Care Authority further expanded the possibilities for the reimbursement of remote, electronic consultations. 64 It became possible to see a patient online already in connection with the first consultation as the ‘old’ requirement that the first consultation should be face‐to‐face was dropped. In England, National Health Service England has set up the Beneficial Changes Network to explore the potential for embedding innovations like electronic consultations in general practice that developed during COVID. There is a support programme and network as well as support for applied research. 65

There were also changes in the form of a new type of provider organisation. The central government in Italy introduced Specialist Units for Continuity of Care. 66 The units are part of the local health authorities, but include different health professions and have a strong intersectoral focus. The units have the statutory duty to manage patients with Covid‐19 who can be treated at home. A final set of changes concerned the health workforce more directly. As part of the expansion of the public health workforce, 67 Germany has seen the creation of a new job function, the contact manager, and many newly employed staff have received basic training in public health surveillance. There are also signs of improved collaboration between public health doctors and family physicians, as well as of greater recognition and acknowledgement of public health doctors at both organisational and policy levels. 67

The range and reach of the capacities demonstrates the significant contribution of the health workforce to health system resilience. This resonates with studies of health professions and the notion, that the interests of health professions and the state are closely connected. 68 , 69 Importantly, during public health emergencies like the COVID‐19 pandemic this connection exists at different levels. Firstly, health professions assume a key role in providing services for citizens in emergency situations, thus helping states to navigate effectively through the crisis. Secondly, health professions have the capacity to mediate between the interests of the state and the citizens, thus helping to maintain the trust and confidence of citizens. Thirdly, health professions are part of the regulatory architecture of healthcare systems and enjoy to different levels of self‐regulatory competencies and capacity. These can be mobilised quickly to maximise governance capacities and establish effective crisis management.

3.2. How do health systems prerequisites influence the capacities of the health workforce?

The influence of health systems is most visible in relation to the substantive areas of healthcare delivery, where the health workforce applies its capacities. For example, in Austria absorptive and adaptive capacities focussed on maintaining and increasing the supply of care workers in elder care. This reflects the structural shortcomings of a health system, where the predominance of the medical division of labour co‐exists with shortages in elder care and a strong reliance on migrant carers. 70 In the Netherlands, similar shortages in elder care were the background for sending regional level hospital nurses to nursing homes to increase nursing home capacity to enable a faster hospital throughput. 2

For the same reasons, the health system in Germany has been strongly hospital‐centred and public health has long remained a poor relation. 71 Here, the first wave of the pandemic has offered a basis for turning public health in municipalities into an area for transformative capacities. 67 In the health system in Italy, the same hospital‐centredness and corresponding poor integration across healthcare sectors formed the background for the introduction of new provider organisations in form of the Specialist Units for Continuity of Care. 72 , 73 In the case of England, many years of austerity policies as well as the prospect of Brexit had led to widespread and increasing shortages of hospital doctors and nurses. 74 , 75 Compared to other countries, maintaining and increasing healthcare workers in hospitals was an even stronger focus in relation to absorptive and adaptive capacities in the first wave of the pandemic.

The influence of health systems is less visible in relation to the specific range of capacities of the health workforce. During the first wave of the pandemic, the absorptive and adaptive capacities were particularly prominent, together with some transformative capacities. The lack of distinct patterns is striking, considering that we have included health systems, which differ on so many counts. In terms of funding, our countries include both National Health Services (Denmark, England, Italy) and Social Insurance Systems (Austria, Germany, Netherlands). There are also significant differences in terms of provision: public hospitals dominate in Denmark and England, whereas the provision of hospital services is more mixed in the other countries. This has implications for the relative integration across sectors, not least between health and social care. The picture is also varied in relation to the governance arrangements. These include elements of federalism (Austria, Germany), corporatism (Austria, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands), and medical self‐regulation (Austria, Germany). Overall, health governance is mostly decentralised, with the exception of England. We had expected that this considerable variety in health system prerequisites would make for more varied capacities of the health workforce in our countries.

3.3. Comparative overview of health systems prerequisites and capacities of health workforce

Major findings of our comparative analysis are summarised below. Table 3 provides an overview of the health system prerequisites and the capacities of the health workforce.

TABLE 3.

Overview of health systems prerequisites and capacities of health workforce

| Health system prerequisites | Capacities of health workforce | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Funding | Provision | Governance | Absorptive | Adaptive | Transformative | |

| Austria | ‐Social insurance funding | ‐Welfare‐mix in provision; | ‐Federalist & corporatist governance; federal government, social insurance & provinces as main players | ‐Specially chartered trains for Romanian carers to return to Austria despite closed borders | ‐Increase in carers (numbers of foreign carers; wage increases & improvement of working conditions) | ‐New service offerings in mental health (online consultations, free hotlines) |

| ‐Additional emergency funding | Weak integration across sectors, | ‐Increase of therapy sessions reimbursed by social insurance; increase in fees | ||||

| ‐Highly flexible allocation of funding | ‐High density of health workforce, but shortages in elder care & mental health; | |||||

| Predominance of medical division of labour | ||||||

| Germany | ‐Social insurance funding | ‐Welfare‐mix in provision; | ‐Federalist and decentralised governance based on corporatism | ‐Redeployment of nurses in hospitals | ‐Recruitment of new staff (more full time staff, returnees to clinical practice, retired workers, foreign trained workers) | ‐Upward mobility of public health staff/doctors (policy & organisational levels) |

| ‐Additional emergency funding, including bonuses for nurses in elder care | Weak integration across sectors | ‐Poor integration of non‐medical professional interests | ‐Cancellation of elective treatment, overtime work, holidays | ‐Establishment of auxiliary hospitals (existing staff & up‐skilled nurses) | ‐Greater collaboration between public health doctors and family physicians | |

| ‐Highly flexible allocation of funding | ‐Overall high workforce density; | |||||

| Predominance of medical division of labour | ||||||

| Netherlands | ‐Social insurance funding | ‐Publicly regulated, private provision; | ‐Governance based on corporatism & medical self‐regulation; increasing decentralisation and marketisation | ‐Increase in capacity in hospitals by partial suspension of quality standards, cancellation of overtime work, holidays | ‐Recruitment of health workers with lapsed registration | ‐New service offerings in mental health (psychological support for health workers) |

| ‐Additional emergency funding, including bonus for nurses | Some integration across sectors | ‐Poor integration of nursing interests | ‐Scaling up of ICU care with new teams | ‐Formalisation of e‐care provision (hospitals, primary care) | ||

| ‐Flexible allocation of funding | ‐High density of health workforce, but shortages in some hospital specialties & elder care | |||||

| Denmark | ‐National and local tax funding | ‐Predominance of public hospitals; | ‐Governance based on public corporatism with broad integration of public & professional interests | ‐Temporary suspension of collective agreements (work responsibilities, working times) | ‐Recruitment of new personnel for Covid‐19 wards | ‐Agreement on reimbursement of newly introduced video consultations in general practice |

| ‐Additional national emergency funding | Strong integration of elder care & municipal health/social care; weaker integration of hospitals, GPs & municipalities weaker | ‐Pandemic recognised as mitigating circumstances for clinical errors | ‐ Refocussing of nested structure of intersectoral/professional meetings at regional/municipal and hospital levels | |||

| ‐Marked shortages in elder care & rural general practice | ‐Redeployment and retraining of existing staff in hospitals & municipalities | ‐Accelerated coordination between hospitals & general practice | ||||

| England | ‐National tax funding | ‐Predominance of public hospitals | ‐Centralised health governance | ‐Redeployment of staff to free bed space and staff capacity in hospitals | ‐Increase in staffing levels (retired staff, new graduates) | ‐Formalisation of increased use of remote consultations in general practice supported by Beneficial Change Network |

| ‐Additional national emergency funding | ‐Poor integration of health & social care | ‐Danger of de‐coupling from local stakeholders | ‐New acute Covid‐19 teams | |||

| ‐Widespread and increasing shortages of hospital doctors & nurses | ||||||

| Italy | ‐National tax funding | ‐High welfare‐mix in provision | ‐Decentralised and fragmented governance | ‐Extension of working hours and flexible management of workforce (central government) | ‐Recruitment of new personnel, mostly with temporary contracts (central government) | ‐Abolishment of entry exams for doctors; introduction of Specialist Units for Continuity of Care (central government) |

| ‐Additional national emergency funding, including bonuses for health workforce | ‐Strong hospital centredness with low integration across sectors | ‐Poor integration of doctors | ‐Postponement of elective surgery and reassigned staff (local hospitals) | ‐Plans for reorganisation of health services (regions) | ||

| ‐Dominance of medical division of labour limits task shifting, strong shortage of nurses and carers, | ‐Reorganisation of service delivery (regions and local providers) | |||||

Abbreviation: COVID‐19, coronavirus disease‐2019.

Sources: Authors' own table; based on expert information; European Observatory on Health Systems and Policy's Health in Transition series [32]. Austria – [48,49,51,62,63,70]; Denmark – [28,47,54,55,56,92]; England – [52,65,74]; Germany – [27,57]; Italy – [57,59,60,61,66,72,73]; Netherlands – [45,46,64].

4. DISCUSSION

Our analysis suggests that in the first wave of the pandemic, the contribution of the health workforce to health system resilience has drawn on different combinations of absorptive, adaptive and transformative capacities. However, we cannot detect any distinct patterns across countries or relate capacities to health systems prerequisites in any systematic way (Table 3).

In some respects, this is highly surprising. The Covid‐19 pandemic has presented health systems with many and significant problems that were quite unexpected. The strength of institutions lies in the fact that they offer stability, for example in relation to the funding, provision and governance of health systems. 32 , 76 Under such circumstances of high uncertainty, these institutions provide a springboard for ‘ready‐made’ responses to the crisis; that is because these responses lie dormant in the institutions and just wait to be activated. Based on this, we should expect stronger path‐dependency concerning the health workforce contribution to health systems resilience as reflected in clear patterns of capacities that vary across different types of health system prerequisites. However, we found that policy responses were quite similar.

In other respects, our findings may not be that surprising. Crises like the Covid‐19 pandemic may require a certain set of responses. Parts of the health workforce need to move to the more acute areas of health service delivery; this inevitably involves new skill mixes as well as task shifting. Similarly, central government needs to play an influential role and irrespective of usual funding mechanisms, the governments in all countries provided additional emergency funding. This is an argument about functionalism and about the power that lies in the nature of the problems at hand. Health policies, here related to the health workforce, develop because they are functional to the external environment, which at present is dominated by the Covid‐19 pandemic. 77

Another argument, why we should not be surprised by our findings relates to the conceptualisation of health systems. Cross‐country comparison has been a growth industry since the early 1990s, and this has enhanced scholarly debate over health systems and typologies. 32 , 78 , 79 For instance, Wendt has presented an elaborate expansion of health system typologies, 80 , 81 which has been further developed by Böhm et al. 82 and most recently by Reibling et al. 83 These typologies include the health workforce as a distinct category next to finance, service provision and health status 81 , 83 or as part of a broader category of physical and human resources. 79 However, the typologies do not consider the specific role and centrality of the health workforce for the functioning of health systems. Our findings underline the fact that the conceptualisation of health systems might probably be all too general to capture the specific institutional prerequisites at play in relation to the health workforce. It might be helpful to pay greater attention to professionalism and the professions in future research and specify the importance for health system resilience.

Recent developments in the literature on health system resilience also highlight this complexity. There is a growing shift from resilience as a capacity of the health system to an acknowledgement that this capacity rests on the ability of actors to adapt, learn and transform health systems. 23 , 24 Kruk et al. 84 define health system resilience as a joint capacity of health actors, institutions and populations. Studies have also moved from treating health system resilience as an output to treating health system as a process. 24 A prominent example is the ‘Operational model of health system resilience’ developed by Chamberland‐Rowe and colleagues, 23 which includes inputs and mediators in addition to outputs. This relates to another change of perspective, namely from top‐down to bottom‐up. An influential example is the emergence of the concept of ‘every‐day resilience’, which puts the interest in the meso‐ and micro‐levels of health service organisation and delivery centre stage. 85 , 86 Similarly, Basara and colleagues 85 stress the importance of what they call the ‘software’ of health system resilience, that is: leadership, power and values, in addition to funding and infrastructures.

The emerging concern for agency in the literature on health system resilience resonates with insights from studies of professions. The health workforce is populated by health professions, who are part and parcel not only of health service delivery, but also of governance arrangements across health systems in Europe. Such governance arrangements are interlinked with the concept of professionalism, which furnishes health professions with a unique capacity to mediate between the ‘state’ and the ‘citizens’ and to ensure trust in institutions and regulatory measures. 33 , 69 , 87 This gives health professions an important strategic position in how health systems respond to the COVID‐19 pandemic. 88 In a situation of crisis and shocks, the power of professionalism might be reinforced, because it can provide guidance for both health policy (through professional experts, scientific knowledge) and frontline practice (through ethical guidelines, professional standards and competencies). Interestingly, professionalism draws on highly standardised regulatory frameworks and knowledge systems, which enjoys highest currency across otherwise different healthcare systems.

Governance can be the key to effective health system responses to the COVID‐19 crisis also more generally. 89 , 90 Transparency, solidarity, coordination, decisiveness, clarity and accountability, among others, are emerging as important issues for managing the COVID‐19 pandemic. 4 , 6 This is interesting because governance opens windows of opportunity for systematically integrating the health workforce (and its professional groups) into the analysis of health systems. 3 , 34 As a ‘middle‐range theory’, 91 governance can inform the analysis of public health problems in highly effective ways. Governance spans across macro‐ and micro‐levels of health systems and may therefore help us to understand resilience ‘from the inside out’, that is the health workforce capacities of its frontline staff, and more generally, the power of professions and professionalism.

4.1. Limitations of the study

We collected data in the first wave of the pandemic, where the levels of uncertainty generally were very high. This offers a unique case for studying the specific capacities of the health workforce when contributing to health systems resilience. However, concerning institutional prerequisites, it may take time for their influence to show. This assumption naturally can only be explored in future research. Furthermore, many shocks are cyclical and therefore allow for learning, as Hanefeld et al. 25 argue. These learning processes might also increase variety of the responses over time. As we were looking at the first cycle of the COVID‐19 pandemic, such opportunities for learning and planning are naturally limited.

It is also important that the different types of healthcare systems included in our sample are all shaped by a common regulatory framework of the European Union and that this framework has been strengthened throughout the Covid‐19 crisis. 40 Institutional pathways might also be more visible, if we had chosen countries that are characterised by a greater variation of institutional prerequisites, for example by including health systems in countries in the Global South. 19

5. CONCLUSION

Our comparative analysis set out to analyse health system resilience with a focus on the health workforce. We sought to identify the specific adaptive, absorptive and transformative capacities of the health workforce, and to assess how health systems influence these capacities. In our comparative analysis, we found that during the first wave of the pandemic, the health workforce in our countries drew on a wide range of capacities. However, our analysis also revealed that different health systems seemed to have little influence of the specific combinations of capacities of the health workforce. This challenges our understanding of health systems and calls for a reconceptualisation of the institutional perquisites of health system resilience, in order to fully grasp the manifold and unique health workforce contribution. Two major conclusions can be drawn from our research. Governance emerges as key to effective health system responses to the COVID‐19 crisis, and health professions are part and parcel of governance as frontline workers and collective actors. One important step forward towards health system resilience, therefore, would be to improve health workforce capacities and strengthen the integration of health professions in health governance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

No conflict of interest declared.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Not applicable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This project did not receive specific funding.

Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Burau V, Falkenbach M, Neri S, Peckham S, Wallenburg I, Kuhlmann E. Health system resilience and health workforce capacities: comparing health system responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in six European countries. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. 2022;37(4):2032‐2048. 10.1002/hpm.3446

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- 1. Campbell J, Dussault G, Buchan J, et al. A Universal Truth: No Health without a Workforce. Third Global Forum on Human Resources for Health. Recife: Brazil; 2013. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.who.int/workforcealliance/knowledge/resources/GHWA‐a_universal_truth_report.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bal R, de Graaf B, van de Bovenkamp H, Wallenburg I. Practicing corona – towards a research agenda on health policies. Health Pol. 2020;124:671‐673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denis J‐L, Côté N, Fleury C, Currie G, Spyridonidis D. Global health and innovation: a panoramic view on health human resources in COVID‐19 pandemic context. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(S1):58‐70. Accessed November 30, 2021. 10.1002/hpm.3129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Van Schalkwyk MCI, Bourek A, Kringos DS, et al. on behalf of the European Commission Expert Panel on Effective ways of Investing in Health. The best person (or machine) for the job: rethinking task shifting in healthcare. Health Pol. 2020;124:1379‐1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gupta N, Balcom SA, Gulliver A, Witherspoon RL. Health workforce surge capacity during the COVID‐19 pandemic and other global respiratory disease outbreaks: a systematic review of health system requirements and responses. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(S1):26‐41. Accessed November 30, 2021. 10.1002/hpm.3137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Forman R, Atun R, McKee M, Mossialos E. 12 lessons learned from the management of the coronavirus. Health Pol. 2020;124:577‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McCauley L, Hayes R. Taking responsibility for front‐line health‐care workers. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e461‐e462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kuhlmann E, Dussault G, Wismar M. Health labour markets and the ‘human face’ of the health workforce: resilience beyond the COVID‐19 pandemic. Eur J Publ Health. 2020;30(Suppl 4):iv1‐iv2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis L, Ehrenberg N. Realising the True Value of Integrated Care: Beyond Covid‐19. International Foundation for Integrated Care; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://integratedcarefoundation.org/covid‐19‐knowledge/realising‐the‐true‐value‐of‐integrated‐care‐beyond‐covid‐1 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thomas S, Sagan A, Larkin J, et al. Strengthening health system resilience. Key concepts and strategies. Policy Brief 36. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Williams G, Maier CB, Scarpetti G, et al. What strategies are countries using to expand health workforce surge capacity during the COVID‐19 pandemic? Eurohealth. 2020;26:51‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zapata T, Buchan J, Azzopardi‐Muscat N. The health workforce: central to an effective response to the COVID‐19 pandemic in Europe. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(S1):9‐13. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/hpm.3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. European Commission . European Semester. European Commission, e‐News 20/05/2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/newsrom/sante/newsletter‐specific‐archive‐issue.cfm?archtype=specific&newsletter_service_id=327&newsletter_issue_id=22416&page=1&fullDate=Wed%2020%20May%202020&lang=default

- 14. WHO Regional Office for Europe . Strengthening and Adjusting Public Health Measures throughout the COVID‐19 Transition Phases. Policy Considerations for the WHO European Region. WHO; 2020. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332467/WHO‐EURO‐2020‐690‐40425‐54211‐eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pan European Commission on Health and Sustainable Development Goals. WHO; 2021. Accessed December 1, 2021. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health‐topics/health‐policy/european‐programme‐of‐work/pan‐european‐commission‐on‐health‐and‐sustainable‐development

- 16. Covid‐19 HSRM. What Strategies Are Countries Using to Expand Health Workforce Surge Capacity to Treat Covid‐19 Patients? Health Systems Response Monitor. WHO; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://analysis.covid19healthsystem.org/index.php/2020/04/23/what‐strategies‐are‐countries‐using‐to‐expand‐health‐workforce‐surge‐capacity‐to‐treat‐covid‐19‐patients/ [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waitzberg R, Aissat D, Habicht T, et al. Compensating healthcare professionals for income losses and extra expenses during COVID‐19. Eurohealth. 2020;26:83‐87. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Williams G, Scarpetti G, Bezzina A, et al. How are countries supporting their health workers during COVID‐19? Eurohealth. 2020;26:58‐62. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lotta G, Fernandez M, Corrêa M. The vulnerabilities of the Brazilian health workforce during health emergencies: analysing personal feelings, access to resources and work dynamics during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;6(S1):42‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sagan A, Thomas S, McKee M, et al. COVID‐19 and health system resilience. Eurohealth. 2020;26. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Therrien M‐C, Normandin J‐M, Denis J‐L. Bridging complexity theory and resilience to develop surge capacity in health systems. J Health Organ Manag. 2017;31:96‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wulff K, Donato D, Lurie L. What is health resilience and how can we build it? Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:361‐374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chamberland‐Rowe C, Chiocchio F, Bourgeault IL. Harnessing instability as an opportunity for health system strengthening: a review of health system resilience. Health Manage Forum. 2019;32:128‐135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Biddle L, Wahedi K, Bozorgmehr K. Health system resilience: a literature review of empirical research. Health Pol Plann. 2020;35:1084‐1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hanefeld J, Mayhew S, Legido‐Quigley H, et al. Towards an understanding of resilience: responding to health system shocks. Health Pol Plann. 2018;33:355‐367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Azzopardi‐Muscat N. A public health approach to health workforce policy development in Europe. Eur J Publ Health. 2020;30(Suppl 4):iv3‐iv4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Köppen J, Hartl K, Maier CB. Health workforce response during Covid‐19: what planning and action at the federal and state in Germany? J Health Plann Manage. 2021;36(S1):71‐91. Accessed November 30, 2021. 10.1002/hpm.3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rasmussen S, Sperling P, Såby Poulsen M, Emmersen J, Andersen S. Medical students for health‐care staff shortages during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:e79‐e80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kluge H. Statement COVID‐19: Taking Stock and Moving Forward Together. WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.euro.who.int/en/media‐centre/sections/statements/2020/statement‐covid‐19‐taking‐stock‐and‐moving‐forward‐together [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kuhlmann E, Falkenbach M, Klasa K, et al. Migrant carers in Europe in times of Covid‐19: a call to action for public health‐informed European health workforce governance. Eur J Publ Health. 2020;30(Suppl 4):iv22‐iv27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naylor MD, Hirschman KB, McCauley K. Meeting the transitional care needs of older adults with COVID‐19. J Ageing Soc Policy. 2020;32:387‐395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Blank RH, Burau V, Kuhlmann E. Comparative Health Policy. 5th ed. Palgrave; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Burau V. Governing through professional experts. In: Dent M, Bourgeault IL, Denis J‐L, Kuhlmann E, eds. Routledge companion to the professions and professionalism. Routledge; 2016:91‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kuhlmann E, Batenburg R, Wismar M, et al. A call for action to establish a research agenda for building a future health workforce in Europe. Health Res Pol Syst. 2018;16:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. European Commission . State of Health in the EU. Companion Report 2021. European Union. Accessed January 1, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/default/files/state/docs/2021_companion_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sagan A, Webb E, Azzopardi‐Muscat N, et al. Health systems resilience during COVID‐19: lessons learned to build back better. Health Policy Series 56. WHO; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blanchet K, Nam SL, Ramalingam B, Pozo‐Martin F. Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: towards a new conceptual framework. Int J Health Pol Manag. 2017;6:431‐435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cylus J, van Ginneken E. How to respond to the COVID‐19 economic and health financing crisis? Eurohealth. 2020;26:25‐28. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jakob M, Nathan NL, Pastorino G, et al. Managing health systems on a seesaw. Eurohealth. 2020;26:63‐67. [Google Scholar]

- 40. De la Mata I. European solidarity during the COVID‐19 crisis. 16‐19. Eurohealth. 2020;26:63‐67. [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Ceukelaire W, Bodini C. We need strong public health care to contain the global corona pandemic. Int J Health Serv. 2020;50:276‐277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sabat I, Neuman‐Böhme S, Elsem Varghese N, et al. United but divided: policy responses and people’s perceptions in the EU during the COVID‐19 outbreak. Health Pol. 2020;124:909‐918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Covid 19 HSRM. How Comparable Are Covid‐19 Mortality across Countries? Health Systems Response Monitor, 4 June. WHO; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://analysis.covid19healthsystem.org/index.php/2020/06/04/how‐comparable‐is‐covid‐19‐mortality‐across‐countries/ [Google Scholar]

- 44. Karanikolos M, McKee M. How comparable is COVID‐19 mortality across countries? Eurohealth. 2020;26:45‐50. [Google Scholar]

- 45. IGJ . Aanvullende maatregelen inzet voormalig‐zorgpersoneel. Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 46. IGJ . Tijdelijke aanpassing tot 1 juli 2020 van voorwaarde collegiaal doorleveren van eigen bereidingen door apothekers tijdens de Covid‐19 pandemie. Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heissel A. Flere års Udvikling Er Sket På Få Måneder. Dagens Medicin; April 1, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://dagensmedicin.dk/flere‐aars‐udvikling‐er‐sket‐paa‐faa‐maaneder/ [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blumental E. Grünes Licht für Korridorzug aus Rumänien. APA‐OTS; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20200507_OTS0228/edtstadlerbode‐gruenes‐licht‐fuer‐korridorzug‐aus‐rumaenien [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kittner D. Pflegerinnen: Erster Sonderzug aus Rumänien fährt ab; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://kurier.at/chronik/welt/erster‐sonderzug‐mit‐pflegekraeften‐aus‐rumaenien‐moeglicherweise‐am‐9‐mai/400830086 [Google Scholar]

- 50. IGJ. Aanvullende maatregelen inzet voormalig‐zorgpersoneel . Inspectie Gezondheidszorg en Jeugd; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kainrath V. Sozialwirtschaft erhöht Gehälter und reduziert ab 2022 die Arbeitszeit; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000116389998/sozialwirtschaft‐reduziert‐arbeitszeit‐ab‐2022 [Google Scholar]

- 52. Clark H. Colchester Hospital Theatre Staff Take on Extra Responsibility in Crisis. OTJ; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. http://otjonline.com/download/operating‐theatre‐journal‐may‐2020.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 53. Meyenburg‐Altwarg I, Martens K. Conception of COVID‐19 auxiliary hospital from nursing management perspective. Health Management.org Journal. 2020;20:364‐367. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pinborg K. Der er sket en acceleration af nogle ad de forandringer, som vi i lang tid har talt om. Dagens Medicin. April 3, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://dagensmedicin.dk/der‐er‐sket‐en‐acceleration‐af‐nogle‐af‐de‐forandringer‐som‐vi‐i‐lang‐tid‐har‐talt‐om/ [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pinborg K. Kommunaldirektør: Coronakrisen Har Set Turbo På Forandringer. Kommunal Sundhed. April 2, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://kommunalsundhed.dk/kommunaldirektoer‐coronakrisen‐har‐sat‐turbo‐paa‐forandringer/ [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pinborg K. Sådan Forbereder Viborg Og Køge Det Tværsektorielle Samarbejde under Coronaepidemien. Dagens Medicin. March 24, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://dagensmedicin.dk/saadan‐forbereder‐viborg‐og‐koege‐det‐tvaersektorielle‐samarbejde‐under‐coronaepidemi/ [Google Scholar]

- 57. Costa Font J, Levaggi R, Turati G. Resilient Managed Competition during Pandemics: Lessons from the Italian Experience during COVID‐19. Health Econ Policy Law; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/health‐economics‐policy‐and‐law/article/resilient‐managed‐competition‐during‐pandemics‐lessons‐from‐the‐italian‐experience‐during‐covid19/B91276983393ED78AD179CC6B72B766F [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Casula M, Terlizzi A, Toth F. I servizi sanitari regionali alla prova del COVID‐19. Revista Italiana di Politiche Pubblich. 2020;3:307‐336. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Neri S. Più Stato e più Regioni. L’evoluzione della governance del Servizio sanitario nazionale e la pandemia. Auton locali Serv sociali. 2020;2:239‐255. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Vicarelli G. Regionalismo sanitario e Covid‐19: punti di forza e di debolezza. In: Giarelli G, Vicarelli G, eds. Libro Bianco. Il Servizio Sanitario Nazionale e la pandemia da Covid 19; 2021:49‐57. Accessed November 30, 2021. http://ojs.francoangeli.it/_omp/index.php/oa/catalog/book/604 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mauro M, Giancotti M. Italian responses to the COVID‐19 emergency: overthrowing 30 years of health reforms? Health Pol. 2021;125:548‐552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zsivkovits B. Österreichischer Bundesverband für Psychotherapie startet Initiative für mehr krankenkassenfinanzierte Plätze; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.ots.at/presseaussendung/OTS_20200622_OTS0114/oesterreichischer‐bundesverband‐fuer‐psychotherapie‐startet‐initiative‐fuer‐mehr‐krankenkassenfinanzierte‐plaetze [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wolf J. Psychotherapie‐Zuschuss für Selbstständige verdoppelt; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.derstandard.at/story/2000117852883/psychotherapie‐zuschuss‐fuer‐selbststaendige‐verdoppelt [Google Scholar]

- 64. NZa. Wegwijzer Bekostiging Digitale Zorg; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://puc.overheid.nl/nza/doc/PUC_280639_22/1/ [Google Scholar]

- 65. NHS England. Beneficial Changes Network; 2021. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.england.nhs.uk/beneficial‐changes‐network/ [Google Scholar]

- 66. Genova A, Favretto AR, Clemente C, et al. Assistenza primaria e Covid‐19: MMG e USCA. In: Giarelli G, Vicarelli G, eds. Libro Bianco. Il Servizio Sanitario Nazionale e la pandemia da Covid‐19; 2021:58‐66. Accessed November 30, 2021. http://ojs.francoangeli.it/_omp/index.php/oa/catalog/book/604 [Google Scholar]

- 67. BMG – Bundesministerium für Gesundheit . Pakt für den Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienst. BMG; 2021. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/service/begriffe‐von‐a‐z/o/oeffentlicher‐gesundheitsheitsdienst‐pakt.html [Google Scholar]

- 68. Burau V. Health professions and the state. In: Cockerham WC, Dingwall R, Quah S, eds. Blackwell encyclopedia on health, illness, behavior and society. Blackwell; 2014:1‐5. Accessed November 30, 2021. 10.1002/9781118410868.wbehibs278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kuhlmann E, von Knorring M, Agartan T. Governance and professions. In: Dent M, Bourgeault IL, Denis J‐L, Kuhlmann E, eds. Routledge companion to the professions and professionalism. Routledge; 2016:31‐44. [Google Scholar]

- 70. ORF . Zeit Im Bild 1. ORF; 2020. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://tvthek.orf.at/profile/ZIB‐1/1203/ZIB‐1/14060396 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Busse R, Blümel M. Health systems review: Germany. Health Syst Transit. 2014;16:1‐296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sanfelici M. The Italian response to the COVID‐19 Crisis: lessons learned and future direction in social development. Int J Community Soc Dev. 2020;2:191‐210. [Google Scholar]

- 73. Neri S. Siamo andati troppo oltre? I processi di ristrutturazione dell’assistenza ospedaliera. In: Giarelli G, Vicarelli G, eds. Libro Bianco. Il Servizio Sanitario Nazionale e la pandemia da Covid 19; 2021:49‐57. 2021. Accessed November 30, 2021. http://ojs.francoangeli.it/_omp/index.php/oa/catalog/book/604 [Google Scholar]

- 74. Charlesworth A. Staff Shortages Left the NHS Vulnerable to the Covid‐19 Storm. Prospect. January 8, 2021. Accessed November 30, 2021. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/politics/nhs‐covid‐nursing‐staff‐shortages [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dayan M, Fahy N, Hervey T, et al. Understanding the Impact of Brexit on Health in the UK. Nuffield Trust; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wilsford D. Path dependency, or why history makes it difficult but not impossible to reform health care systems in a big ways. J Publ Pol. 1994;14:251‐283. [Google Scholar]

- 77. Paton C. Health policy: overview. International Encyclopaedia of Public Health. 2nd ed. Elsevier; 2016:438‐449. [Google Scholar]

- 78. Burau V, Blank RB, Pavolini E. Typologies of healthcare systems. In: Kuhlmann E, Bank RB, Bourgeault IB, Wendt C, eds. International handbook of healthcare policy and governance. Palgrave; 2015:101‐115. [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cylus J, Papanicolas I. Comparison of health systems performance. In: Kuhlmann E, Bank RB, Bourgeault IB, Wendt C, eds. International handbook of healthcare policy and governance. Palgrave; 2015:116‐132. [Google Scholar]

- 80. Wendt C. Changing healthcare system types. Soc Pol Adm. 2014;48:864‐882. [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wendt C, Kohl J. Translating monetary inputs into health care provision: a comparative analysis of the impact of different modes of public policy. J Comp Pol Anal. 2010;12:11‐31. [Google Scholar]

- 82. Böhm K, Schmidt A, Götze R, et al. Five types of OECD healthcare systems: empirical results of a deductive classification. Health Pol. 2013;113:258‐269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Reibling N, Aarians M, Wendt C. Worlds of health: a health system typology of OECD countries. Health Pol. 2019;123:611‐620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kruk ME, Ling EJ, Bitton A, et al. Building resilient health systems: a proposal for a resilience index. BMJ. 2017;357:j2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Barasa EW, Cloete K, Gilson L. From bouncing back, to nurturing emergence: reframing the concept of resilience in health systems strengthening. Health Pol Plann. 2017;32(Suppl 3):iii91‐iii94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Gilson L, Ellokor S, Lehmann U, Brady L. Organizational change and everyday health system resilience: lessons from Cape Town, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2020;266:113407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Kuhlmann E, Burau V. The ‘healthcare state’ in transition: national and international contexts of changing professional governance. Eur Soc. 2008;10:619‐633. [Google Scholar]

- 88. Gofen A, Lotta G. Street‐level bureaucrats at the forefront of pandemic response: a comparative perspective. J Comp Pol Anal. 2021;23:3‐15. [Google Scholar]

- 89. Greer SL, Jarman H, Rozenblum S, Wismar M. Who is in charge and why? Centralisation within and between governments. Eurohealth. 2020;26:99‐103. [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jarman H, Greer SL, Rozenblum S, Wismar M. In and out of lockdowns, and what is a lockdown anyway? Eurohealth. 2020;26:93‐98. [Google Scholar]

- 91. Greer SL, Bekker MPM, Azzopardi‐Muscat N, McKee M. Political analysis in public health: middle range concepts to make sense of the politics of health. Eur J Publ Health. 2018;28(Suppl 3):3‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.