Short abstract

In response to the World Health Organization (WHO) statements and international concerns regarding the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak, FIGO has issued comprehensive guidance for the management of pregnant women.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, COVID‐19, management, pneumonia, pregnancy, puerperium, SARS‐CoV‐2

1.

| Contents |

| 1. Goals of the guidelines |

| 2. Background |

| 3. Diagnosis of infection and clinical classification |

| 4. Chest radiography during pregnancy |

| 5. Medical treatment of pregnant women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 |

| 6. Antenatal care in outpatient clinics (Algorithm 1) |

| 7. Assessment of women in obstetrical triage (Algorithm 2) |

| 8. Intrapartum management of women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 (Algorithm 3) |

| 9. Postpartum and neonatal care in women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 (Algorithm 4) |

| 10. Psychological intervention |

| 11. General precautions |

| 12. Management of biohazardous material |

| 13. Key points for consideration |

2. Goals of the Guidelines

In response to the World Health Organization (WHO) statements and international concerns regarding the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak, FIGO has issued the following guidance for the management of pregnant women at the four main settings of pregnancy: (1) ambulatory antenatal care in the outpatient clinics; (2) management in the setting of the obstetrical triage; (3) intrapartum management; and (4) postpartum management and neonatal care. We also provide guidance on the medical treatment of pregnant women with COVID‐19 infection.

The recommendations included in the current document should be viewed as suggestions and may need to be adjusted within each medical center based on the local national guidance (when available), needs, resources, and limitations. Furthermore, this statement is not intended to replace previously published interim guidance on evaluation and management of COVID‐19‐exposed pregnant women. It should therefore be considered in conjunction with other relevant advice from organizations such as:

WHO: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/specific-groups/pregnancy-faq.html

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO): http://www.paho.org

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): https://www.ecdc.europa.eu

Public Health England: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-the-public

National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China: http://www.nhc.gov.cn

Maternal and Fetal Experts Committee, Chinese Physicians Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chinese Medical Doctor Association, Obstetric Working Group, Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chinese Medical Association: http://rs.yiigle.com/yufabiao/1179570.htm; http://zhwcyxzz.yiigle.com

Societa Italiana di Neonatologia (SIN): https://www.policlinico.mi.it/uploads/fom/attachments/pagine/pagine_m/79/files/allegati/539/allattamento_e_infezione_da_sars-cov-2_indicazioni_ad_interim_della_societ___italiana_di_neonatologia_sin__2_.pdf

Santé Publique France: https://www.santepubliquefrance.fr/

Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (SEGO): https://mcusercontent.com/fbf1db3cf76a76d43c634a0e7/files/1abd1fa8-1a6f-409d-b622-c50e2b29eca9/RECOMENDACIONES_PARA_LA_PREVENCIO_N_DE_LA_INFECCIO_N_Y_EL_CONTROL_DE_LA_ENFERMEDAD_POR_CORONAVIRUS_2019_COVID_19_EN_LA_PACIENTE_OBSTE_TRICA.pdf

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG): https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-03-28-covid19-pregnancy-guidance.pdf

Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC): https://sogc.org/en/content/featured-news/Updated-SOGC-Committee-Opinion%E2%80%93%20COVID-19-in-Pregnancy.aspx

Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology (SOAP): https://soap.org/education/provider-education/expert-summaries/interim-considerations-for-obstetric-anesthesia-care-related-to-covid19/

International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology (ISUOG): https://obgyn.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/uog.22013

The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (RANZCOG): https://ranzcog.edu.au/statements-guidelines/covid-19-statement

The Indian Council of Medical Research. Revised Strategy of COVID19 testing in India (Version 3, dated March 20, 2020): https://icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/upload_documents/2020-03-20_covid19_test_v3.pdf

Federation of Obstetrics and Gynaecological Societies of India: https://www.fogsi.org/advisory-on-covid-19-pandemic/

3. Background

COVID‐19, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), is a global public health emergency. Coronaviruses are enveloped, nonsegmented, positive‐sense ribonucleic acid (RNA) viruses belonging to the family Coronaviridae, order Nidovirales.1 The epidemics of the two notable β‐coronaviruses, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV), have caused more than 10 000 cumulative cases in the past two decades, with mortality rates of 10% for SARS‐CoV and 37% for MERS‐CoV.2, 3, 4, 5, 6 COVID‐19 belongs to the same β‐coronavirus subgroup and shares genome similarity of about 80% and 50% with SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV, respectively.7

SARS‐CoV‐2 is spread by respiratory droplets and direct contact (when bodily fluids have touched another person's eyes, nose, or mouth, or an open cut, wound, or abrasion). It should be noted that the SARS‐CoV‐2 virus has been found to be viable on plastic and stainless steel surfaces for up to 72 hours, whereas on copper and cardboard it is viable for up to 24 hours.8

The Report of the WHO–China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19)9 estimated a high R 0 (reproduction number) of 2–2.5. The report from WHO,10 on March 3, 2020, estimated the global mortality rate of COVID‐19 infection to be 3.4%; however, further reports, which used proper adjustment for the case ascertainment rate and for the delay between symptoms onset and death, suggested the mortality rate to be lower at 1.4%.11

Huang et al.12 first reported on a cohort of 41 patients with laboratory‐confirmed COVID‐19 pneumonia. They described the epidemiological, clinical, laboratory, and radiological characteristics, as well as treatment and clinical outcome of the patients. Subsequent studies with larger sample sizes have shown similar findings.13, 14 A meta‐analysis15 of eight studies, including 46 248 infected patients, has shown that the most prevalent clinical symptom is fever (91% ± 3; 95% CI, 86–97), followed by cough (67% ± 7; 95% CI, 59–76), fatigue (51% ± 0; 95% CI, 34–68), and dyspnea (30% ± 4; 95% CI, 21–40). The most prevalent comorbidities are hypertension (17% ± 7; 95% CI, 14–22) and diabetes (8% ± 6; 95% CI, 6–11), followed by cardiovascular diseases (5% ± 4; 95% CI, 4–7) and respiratory system disease (2% ± 0; 95% CI, 1–3).

The hallmark of treatment of patients with COVID‐19 infection is supportive care. Recent studies have suggested possible benefit of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin,16 while no benefit has been seen with the combination of lopinavir and ritonavir in hospitalized adult patients with severe COVID‐19 infection.17 However, these findings should be further investigated in larger trials.

3.1. COVID‐19 and pregnancy

Pregnancy is a physiological state that predisposes women to viral respiratory infection. Due to the physiological changes in the immune and cardiopulmonary systems, pregnant women are more likely to develop severe illness after infection with respiratory viruses. In 2009, pregnant women accounted for 1% of patients infected with influenza A subtype H1N1 virus, but they accounted for 5% of all H1N1‐related deaths.18 In addition, SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV are both known to be responsible for severe complications during pregnancy, including the need for endotracheal intubation, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), renal failure, and death.6, 19 The case fatality rate of SARS‐CoV infection among pregnant women is up to 25%.6 Currently, however, there is no evidence that pregnant women are more susceptible to COVID‐19 infection or that those with COVID‐19 infection are more prone to developing severe pneumonia.

Pregnancy may also modify the clinical manifestation, for example lymphocytopenia may be even more marked. To date, summarized data from five small series including 56 pregnant women diagnosed with COVID‐19 during the second and third trimester demonstrated that the most common symptoms at presentation were fever and cough; two‐thirds of patients had lymphopenia and increased C‐reactive protein, and 83% of cases had chest CT scan showing multiple patches of ground‐glass opacity in the lungs.20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Over and above the impact of COVID‐19 infection on a pregnant woman, there are concerns relating to the potential effect on fetal and neonatal outcome; therefore, pregnant women require special attention in relation to prevention, diagnosis, and management.

Fever is common in COVID‐19‐infected patients. Previous data have demonstrated that maternal fever in early pregnancy can cause congenital structural abnormalities involving the neural tube, heart, kidneys, and other organs.25, 26, 27 However, a recent study including 80 321 pregnant women reported that the rate of fever in early pregnancy was 10%, while the incidence of fetal malformation in this group was 3.7%.28 Among the 77 344 viable pregnancies with data collected at 16–29 weeks of pregnancy, in the 8321 pregnant women with a reported temperature above 38°C lasting 1–4 days in early pregnancy, compared with those without a fever in early pregnancy, the overall risk of fetal malformation was not increased (odds ratio [OR]=0.99 (95% CI, 0.88–1.12).28

It has been reported that viral pneumonia in pregnant women is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth, fetal growth restriction (FGR), and perinatal mortality.29 Based on nationwide population‐based data it was demonstrated that pregnant women with other viral pneumonias (n=1462) had an increased risk of preterm birth, FGR, and having a newborn with low birth weight and an Apgar score of less than 7 at 5 minutes, compared with those without pneumonia (n=7310).30 A case series of 12 pregnant women with SARS‐CoV in Hong Kong, China, reported three maternal deaths; four of seven patients who presented in the first trimester had miscarriage; four of five patients had preterm birth; and two mothers recovered without delivery but their ongoing pregnancies were complicated by FGR.6

In relation to neonatal outcomes in COVID‐19 pneumonia, in the study by Chen et al.20 all nine live births had a 1‐minute Apgar score of 8–9 and a 5‐minute Apgar score of 9–10. Amniotic fluid, cord blood, and neonatal throat swab from six patients were tested for SARS‐CoV‐2, and all samples tested negative for the virus, suggesting there was no evidence of vertical transmission in women who developed COVID‐19 pneumonia in late pregnancy. Two cases of neonatal COVID‐19 infections have been reported but both were most likely an outcome of postnatal transmission. Another study analyzing 38 pregnancies demonstrated that similar to pregnancies with SARS‐CoV and MERS‐CoV, there were no confirmed cases of vertical transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2 from mothers with COVID‐19 to their fetuses.31 All neonatal specimens tested, including placentas in some cases, were negative by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT‐PCR) for SARS‐CoV‐2.31 At this point in the global pandemic of COVID‐19 infection there is no evidence that SARS‐CoV‐2 undergoes intrauterine or transplacental transmission from infected pregnant women to their fetuses. While this is reassuring, larger data are needed to firmly rule out transplacental vertical transmission.

3.2. Pregnancy comorbidities and COVID‐19 infection

Given the higher risk of infection and poorer outcomes, including very high mortality, among the elderly population and those with comorbidities (in particular diabetes, hypertension, etc. as noted by Yang et al.15), it is important to consider the potential impact of pre‐existing hyperglycemia and hypertension on the outcome of COVID‐19 in pregnant women. There are at present no studies to guide us on this aspect, but based on evidence from nonpregnant women it would be logical to assume that the risk of acquiring and presenting with more severe clinical manifestations in pregnant women with these comorbidities, hyperglycemia in particular, will be higher. The higher risk of acquiring SARS‐CoV‐2 in pregnant women with hyperglycemia may also be partly related to greater risk of exposure due to more frequent visits to healthcare facilities for follow‐up. The stress of infection, accompanied by severe anxiety and use of high doses of corticosteroids, is likely to worsen glycemic control and enhance the risk of secondary infections and thus requires careful consideration in management. Similarly, women with pre‐existing or pregnancy hypertension may have a higher risk of manifesting pre‐eclampsia and its consequences. There is currently no evidence to guide on these aspects; however, it is important to highlight that one in seven pregnancies is impacted by hyperglycemia and one in 10 is impacted by hypertension. These issues must be kept in mind in the clinical management, along with the importance of noting the presence of these conditions to enable collection of more data that would guide informed decisions. At this point, the clinical management of these conditions must follow established protocols, including screening for pre‐eclampsia and initiation of aspirin prophylaxis.32 Women with hyperglycemia should preferably receive insulin in case medical therapy is required.

Based on the limited information available currently and our knowledge of other similar viral pulmonary infections, the following expert opinions are offered to guide clinical management.

4. Diagnosis of Infection and Clinical Classification

Case definitions are those included in the WHO's interim guidance, “Global surveillance for COVID‐19 caused by human infection with COVID‐19 virus”. 33

4.1. Suspected case

A patient with acute respiratory illness (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease (e.g. cough, shortness of breath) AND with no other etiology that fully explains the clinical presentation AND a history of travel to or residence in a country/area or territory reporting local transmission of COVID‐19 infection during the 14 days prior to symptom onset; OR

A patient with any acute respiratory illness AND who has been in contact with a confirmed or probable COVID‐19 case (see definition of contact below) in the 14 days prior to onset of symptoms; OR

A patient with severe acute respiratory infection (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease (e.g. cough, shortness breath) AND requiring hospitalization AND with no other etiology that fully explains the clinical presentation.

4.2. Probable case

A suspected case for whom laboratory testing for COVID‐19 is inconclusive.

4.3. Confirmed case

A person with laboratory confirmation of COVID‐19 infection, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms.

Any suspected case should be tested for COVID‐19 infection using available molecular tests, such as qRT‐PCR. Lower respiratory tract specimens likely have a higher diagnostic value compared with upper respiratory tract specimens for detecting COVID‐19 infection. WHO recommends that, if possible, lower respiratory tract specimens, such as sputum, endotracheal aspirate, or bronchoalveolar lavage be collected for COVID‐19 testing. If patients do not have signs or symptoms of lower respiratory tract disease or specimen collection for lower respiratory tract disease is clinically indicated but collection is not possible, upper respiratory tract specimens of combined nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs should be collected. If initial testing is negative in a patient who is strongly suspected of having COVID‐19 infection, the patient should be resampled, with a sampling time interval of at least 1 day and specimens collected from multiple respiratory tract sites (nose, sputum, endotracheal aspirate). Additional specimens, such as blood, urine, and stool may be collected to monitor the presence of virus and the shedding of virus from different body compartments. When qRT‐PCR analysis is negative for two consecutive tests, COVID‐19 infection can be ruled out.

Definition of contact: A contact is a person involved in any of the following:

Providing direct care for COVID‐19 patients without using proper personal protective equipment (PPE).

Being in the same close environment as a COVID‐19 patient (including sharing workplace, classroom, or household, or attending the same gathering).

Traveling in close proximity (within 2 meters or 6 feet) to a COVID‐19 patient in any kind of conveyance.

In order to ensure access to specialized care, pregnant women who are symptomatic may need to be prioritized for testing. 33

WHO has provided guidance on the rational use of PPE for COVID‐19. When conducting aerosol‐generating procedures (e.g. tracheal intubation, noninvasive ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, manual ventilation before intubation), healthcare workers are advised to use respirators (e.g. N95, FFP2 or equivalent standard) with their PPE. 34 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) additionally considers procedures that are likely to induce coughing (e.g. sputum induction, collection of nasopharyngeal swabs, suctioning) as aerosol‐generating procedures. 35

5. Chest Radiography During Pregnancy

Chest imaging, especially CT scan, is essential for evaluation of the clinical condition of a pregnant woman with COVID‐19 infection. 36 , 37 , 38 FGR, microcephaly, and intellectual disability are the most common adverse effects from high‐dose (>610 mGy) radiation exposure. 39 , 40 , 41 According to data from the American College of Radiology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, when a pregnant woman undergoes a single chest X‐ray examination, the radiation dose to the fetus is 0.0005–0.01 mGy, which is negligible, while the radiation dose to the fetus is 0.01–0.66 mGy from a single chest CT or CT pulmonary angiogram. 42 , 43 , 44

Chest CT scanning has high sensitivity for diagnosis of COVID‐19. 38 In a pregnant woman with suspected COVID‐19 infection, a chest CT scan may be considered as a primary tool for the detection of COVID‐19 in epidemic areas. 38 Informed consent should be obtained and a radiation shield applied over the gravid uterus.

6. Medical Treatment of Pregnant Women With Suspected or Confirmed COVID‐19

6.1. Place of care

Suspected, probable, and confirmed cases of COVID‐19 infection should be managed initially by designated tertiary hospitals with effective isolation facilities and protection equipment. Suspected/probable cases should be treated in isolation and confirmed cases should be managed in a negative pressure isolation room, although it is recognized that these may be unavailable in many units. In general, critically ill confirmed cases should be admitted to a negative pressure isolation room in an ICU. 45 However, we are all aware that this capacity can be rapidly filled. Ideally, designated hospitals should set up a dedicated negative pressure operating room and a neonatal isolation ward. All attending medical staff should wear appropriate PPE (respirator, goggles, face‐protective shield, water‐resistant surgical gown, gloves) when providing care for suspected/probable/confirmed cases of COVID‐19 infection. 46

In areas with widespread local transmission of the disease, healthcare services in both high‐ and low‐income countries may be unable to provide such levels of care to all suspected/probable/confirmed cases. Pregnant women with a mild clinical presentation may not initially require hospital admission, and home confinement can be considered provided that this is possible logistically and that monitoring of the woman's condition can be ensured without compromising the safety of her family. 47 If negative pressure isolation rooms are not available, patients should be isolated in single rooms or grouped together once COVID‐19 infection has been confirmed.

For transfer of confirmed cases, the attending medical team should wear appropriate PPE and keep themselves and their patient a minimum distance of 2 meters or 6 feet from any individuals without PPE.

6.2. Treatment of suspected/probable cases

General treatment: maintain fluid and electrolyte balance; symptomatic treatment, such as antipyretic, antidiarrheal medicines. While concerns have been raised in the medical literature about the potential risk of exacerbation of viral load with use of ibuprofen, WHO—based on currently available information—does not recommend against its use. 48

Maternal surveillance: close and vigilant monitoring of vital signs and oxygen saturation level to minimize maternal hypoxia; conduct arterial blood‐gas analysis; repeat chest imaging (when indicated); regular evaluation of complete blood count, renal and liver function testing, and coagulation testing.

Fetal surveillance: undertake cardiotocography (CTG) for fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring when gestational age is beyond the limit of viability based on local practice (23–28 weeks). The pregnancy should be managed according to the clinical findings, regardless of the timing of infection during pregnancy. All visits for obstetric emergencies should be offered in agreement with current local guidelines. All routine follow‐up appointments should be postponed by 14 days or until positive test results (or two consecutive negative test results) are available.

6.3. Treatment of confirmed

6.3.1. Mild disease

The approach to maintaining fluid and electrolyte balance, symptomatic treatment, and surveillance is the same as for suspected/probable cases.

Currently there is no proven antiviral treatment for COVID‐19 patients, although antiretroviral drugs are being trialed therapeutically on patients with severe symptoms. 49 , 50 If antiviral treatment is to be considered, this should be done following careful discussion with virologists; pregnant patients should be counseled thoroughly on the potential adverse effects of antiviral treatment for the patient herself as well as for the risk of FGR. Clinical trials on potential treatment modalities for COVID‐19 are being undertaken in many countries and in some, such as the UK, pregnant women are eligible for recruitment.

Monitoring for bacterial infection (blood culture, midstream or catheterized specimen urine microscopy and culture) should be done, with timely use of appropriate antibiotics when there is evidence of secondary bacterial infection.

Fetal surveillance: undertake CTG for FHR monitoring when gestational age is beyond the limit of viability based on local practice (23–28 weeks).

6.3.2. Severe and critical disease

The degree of severity of COVID‐19 pneumonia is defined by the Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society guidelines for community‐acquired pneumonia. 51

Severe pneumonia is associated with a high maternal and perinatal mortality rate, therefore aggressive treatment is required, including supporting measures with hydration and oxygen therapy. The patient should be managed in a negative pressure isolation room in the ICU, preferably in a left lateral position, with the support of a multidisciplinary team (obstetricians, maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, intensivists, obstetric anesthetists, internal medicine or respiratory physicians, midwives, virologists, microbiologists, neonatologists, infectious disease specialists). 52

Antibacterial treatment: appropriate antibiotic treatment in combination with antiviral treatment should be used promptly when there is suspected or confirmed secondary bacterial infection, following discussion with microbiologists.

Appropriate blood pressure monitoring and fluid balance management.

Oxygen therapy: supplemental oxygen should be used to maintain oxygen saturation equal to or greater than 95% 53 , 54 ; oxygen should be given promptly to patients with hypoxemia and/or shock, 55 and method of ventilation should be according to the patient's condition and following guidance from the intensivists and obstetric anesthetists.

Alternative therapy: pathologic findings, including macroscopic hemorrhagic areas, and microthrombi in severely dilated blood vessels, have been identified in the lungs and liver of 50 COVID‐19 fatalities from one center in Lombardy, Italy (unpublished data). Based on these observations, there is consideration for the use of low molecular weight heparin in severe cases; however, its efficacy in improving the outcomes of severe COVID‐19 pneumonia requires further investigation before formal recommendation.

Fetal surveillance: if appropriate, CTG for FHR monitoring should be undertaken when gestational age is beyond the limit of viability based on local practice (23–28 weeks).

Medically indicated preterm delivery should be considered by the multidisciplinary team on a case‐by‐case basis. For women with severe disease who are at less than 32 weeks of pregnancy (but are beyond the threshold of viability), a transfer to a center with a level 2 or level 3 neonatal ICU should be considered (if this service is not available at the local center) due to the increased risk for indicated preterm birth.

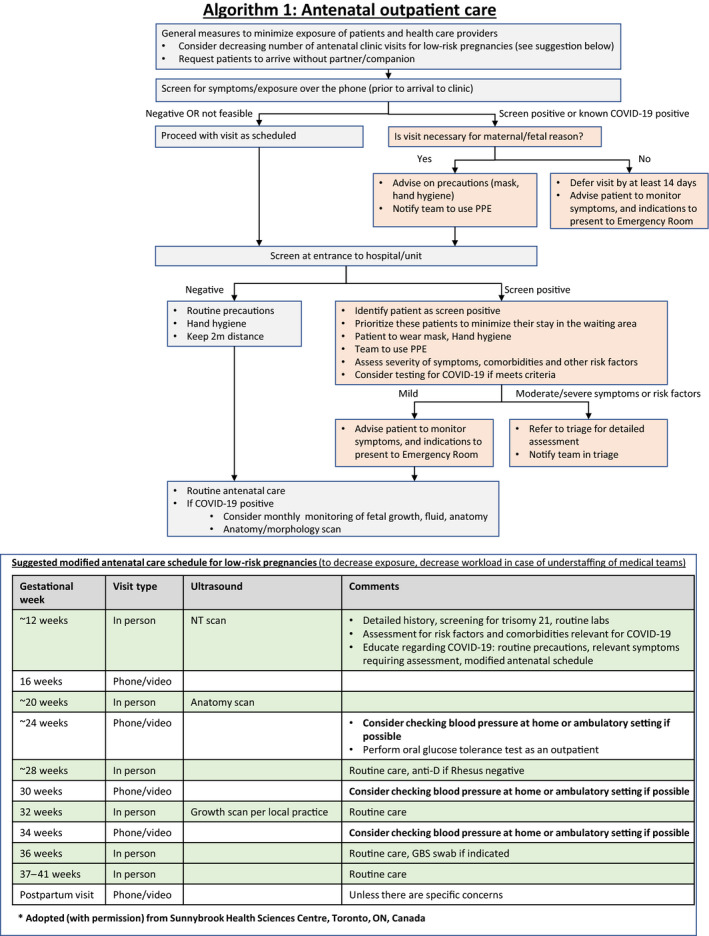

7. Antenatal Care in Outpatient Clinics (Algorithm 1)

Special attention should be given to women with associated comorbidities like hyperglycemia and hypertension and existing management protocols must be followed, with the exception that women with COVID‐19 pneumonia and associated hyperglycemia in pregnancy requiring medical therapy should preferably be shifted to insulin therapy.

Several precautions should be taken to minimize the risk of transmission between pregnant women, healthcare providers, and other patients in the hospital. The number of clinic visits in low‐risk women with uncomplicated pregnancy can be decreased and replaced by virtual visits using phone or video calls. Women may be advised to check their blood pressure at home if possible, with appropriate advice given regarding when to seek medical assistance.

A suggestion for a modified schedule is illustrated in Algorithm 1 (Fig. 1) and has also been recommended by others. 56 In addition, it is useful to contact women prior to clinic visit to request that they arrive without a companion, as well as to screen them for symptoms or exposure relevant to COVID‐19. In cases of positive screen, the visit should be deferred by 14 days unless the visit is urgent for maternal and/or fetal reasons, in which case the healthcare providers should be made aware and they should use proper personal protection procedures.

Figure 1.

Algorithm 1: Antenatal outpatient care.

It is also advised that all patients undergo screening at the entrance to the clinic or medical center. In cases of positive screen, the patient should be asked to wear a mask. The patient should be identified as screen positive to ensure that the team takes the necessary precautions and to ensure that the patient is seen with high priority to minimize her time in the waiting area. In addition to the routine obstetrical care, patients that screen positive should be evaluated for the presence and severity of symptoms, and testing for COVID‐19 should be considered based on local protocols. Patients should be educated regarding monitoring symptoms and indications for seeking urgent care.

Although there is currently no evidence that COVID‐19 infection is associated with fetal or placental complications, until more data become available we advise closer fetal monitoring of women with confirmed COVID‐19 infection, with monthly ultrasound for fetal growth, amniotic fluid, and fetal anatomy (Algorithm 1). Previous studies have reported no evidence of congenital infection with SARS‐CoV, 57 and currently there are no data on the risk of congenital malformation when COVID‐19 infection is acquired during the first or early second trimester of pregnancy. Nonetheless, a detailed morphology scan at 18–23 weeks of pregnancy is indicated for pregnant women with confirmed COVID‐19 infection.

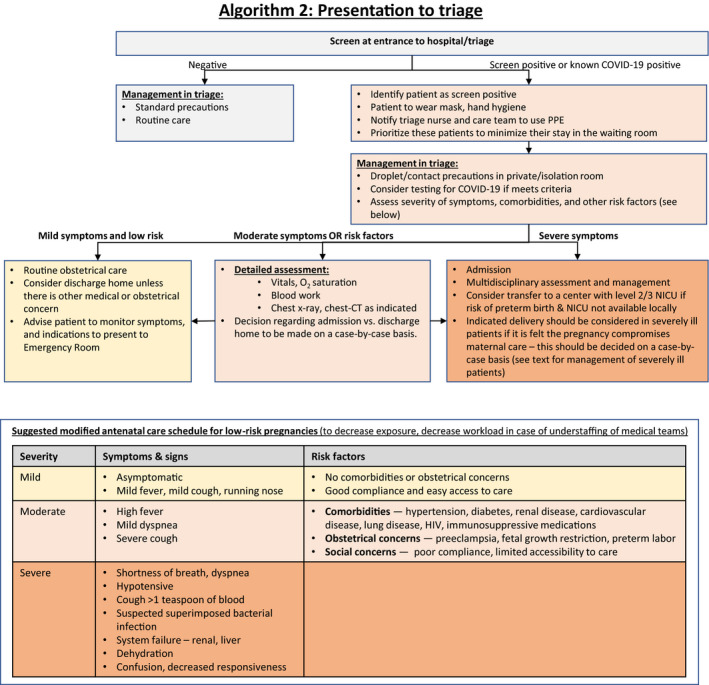

8. Assessment of Women in Obstetrical Triage (Algorithm 2)

When a patient presents to the obstetrical triage or emergency department for respiratory or obstetrical reasons, she should be screened for symptoms or exposure relevant to COVID‐19 infection. In cases of positive screen, the patient should be asked to wear a mask and the team should take the necessary contact precautions. The patient should be assessed in an isolation or private room. Symptoms and vital signs should be evaluated, and testing for SARS‐CoV‐2 should be considered based on local criteria. Assessment should also include evaluation of comorbidities and other risk factors for severe COVID‐19 infection.

Women with mild symptoms with no risk factors for severe disease may be discharged home after being advised to monitor symptoms and to seek care in case the symptoms worsen (Fig. 2: Algorithm 2).

Figure 2.

Algorithm 2: Presentation to triage.

Women with moderate disease or those who have comorbidities or other risk factors for severe COVID‐19 infection (see Algorithm 2) should undergo detailed assessment including physical examination, laboratory testing, and chest radiography as indicated. Decision regarding further management should be individualized based on the symptoms, risk factors, and the results of the assessment.

Women with severe symptoms (see Algorithm 2) should undergo detailed assessment by a multidisciplinary team that includes obstetricians, maternal–fetal subspecialists, intensivists, obstetric anesthetists, internal medicine or respiratory physicians, midwives, virologists, microbiologists, neonatologists and infectious disease specialists, and should be managed as described in section 5.

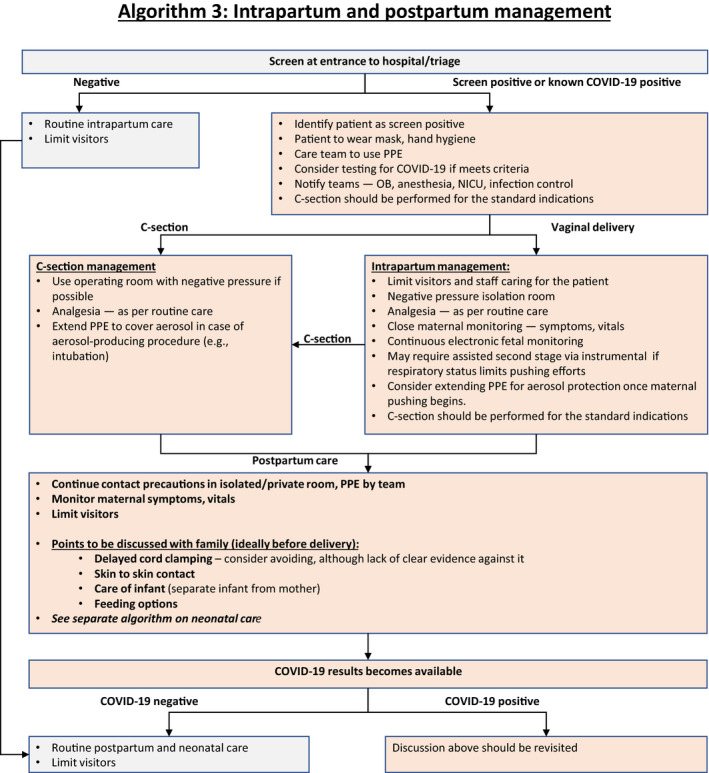

9. Intrapartum Management of Women with Suspected or Confirmed COVID‐19 (Algorithm 3)

COVID‐19 infection itself is not an indication for delivery, unless there is a need to improve maternal oxygenation. For suspected/probable/confirmed cases of COVID‐19 infection, delivery should ideally be conducted in a negative pressure isolation room. For suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 patients, birthing partners should not be permitted to reduce risk exposure (they are likely to be infected). The number of staff members caring for the patient should be as low as possible.

The timing and mode of delivery should be individualized, dependent mainly on the clinical status of the patient, gestational age, and fetal condition. 58 Vaginal delivery is not contraindicated in suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 patients. Shortening the second stage by operative vaginal delivery can be considered, as active pushing while wearing a surgical mask may be difficult for the woman to achieve. 59 There should be a low threshold to expedite the delivery when there is fetal distress, poor progress in labor, and/or deterioration in maternal condition.

Septic shock, acute organ failure, or fetal distress should prompt emergency cesarean delivery (or termination, if legal, before fetal viability). 60 Cesarean delivery should be performed ideally in an operating room with negative pressure.

For the protection of the medical team, the use of birthing pools in hospital should be avoided, given evidence of virus in feces and the inability to use adequate protection equipment for healthcare workers during water birth.

- Both regional anesthesia and general anesthesia can be considered, depending on the clinical condition of the patient and after consultation with the obstetric anesthetist, in accordance with recommendations of obstetric anesthesia societies. 61 Regional anesthesia is preferable given the risk to the staff. Staff should consider extending PPE to cover aerosols in case of aerosol‐producing procedures such as intubation (Fig. 3: Algorithm 3). This is why most units around the world are trying to avoid cesarean delivery under general anesthesia where at all possible.

Figure 3.

Algorithm 3: Intrapartum and postpartum management.

Algorithm 3: Intrapartum and postpartum management. For preterm cases requiring delivery, we urge caution regarding the use of antenatal corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation in a critically ill patient, because this can potentially worsen the clinical condition 62 and the administration of antenatal steroids would delay the delivery that is necessary for management of the patient. The use of antenatal steroids should be considered in discussion with infectious disease specialists, maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, and neonatologists. 56 , 63 In the case of an infected woman presenting with spontaneous preterm labor, tocolysis should not be used in an attempt to delay delivery to administer antenatal steroids.

Miscarried embryos/fetuses and placentae of COVID‐19‐infected pregnant women should be treated as infectious tissues and they should be disposed of appropriately; if possible, testing of these tissues for SARS‐CoV‐2 by qRT‐PCR should be undertaken.

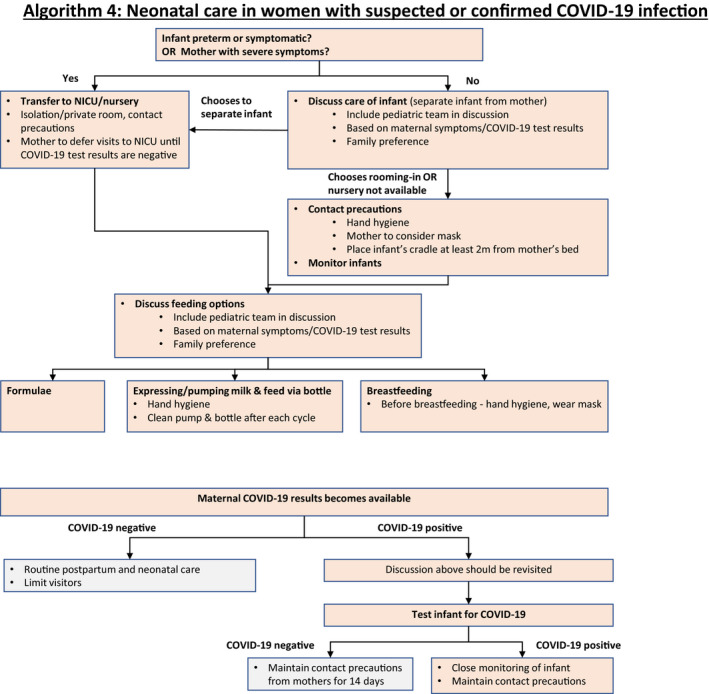

10. Postpartum and Neonatal Care in Women with Suspected or Confirmed COVID‐19 (Algorithm 4)

Regarding neonatal management of suspected, probable, and confirmed cases of maternal COVID‐19 infection, the umbilical cord should be clamped promptly and the neonate should be transferred to the resuscitation area for assessment by the attending pediatric team. There is insufficient evidence regarding whether delayed cord clamping increases the risk of infection to the newborn via direct contact. 59 In units in which delayed cord clamping is recommended, clinicians should consider carefully whether this practice should be continued.

The contact precautions and use of PPE should be maintained during the postpartum period, until the mother tests negative for COVID‐19.

- There is currently insufficient evidence regarding the safety of breastfeeding and the need for mother/baby separation. 20 , 21 , 64 If the mother is severely or critically ill, separation appears to be the best option, with attempts to express breastmilk to maintain milk production. There should be a dedicated breast pump and after each pumping, the device must be thoroughly washed according to manufacturer's recommendations. 64 If the patient is asymptomatic or mildly affected, breastfeeding and colocation (also called rooming‐in) can be considered by the mother in coordination with healthcare providers, or may be necessary if facility limitations prevent mother/baby separation. Since the main concern is that the virus may be transmitted by respiratory droplets rather than breastmilk, breastfeeding mothers should ensure that they wash their hands and wear a three‐ply surgical mask before touching the baby. When rooming‐in, the baby's cot should be kept at least 2 meters or 6 feet from the mother's bed, and a physical barrier such as a curtain may be used (Fig. 4: Algorithm 4). 65 , 66 The mother could be asked to express breastmilk while someone else feeds the baby.

Figure 4.

Algorithm 4: Neonatal care in women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 infection.

Algorithm 4: Neonatal care in women with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 infection. The majority of postpartum visits may be conducted remotely as long as the patient does not have specific concerns that require in‐person examination. Certain concerns (breast, abdominal scar) may be assessed over video or photos. Decreasing the number of visits may be also valuable in the event of shortage of healthcare providers as it is possible that a considerable proportion of healthcare workers will need to be isolated due to unexpected exposure to COVID‐19.

11. Psychological Intervention

Pregnant women are at an increased risk for anxiety and depression; once they have been defined with suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 infection they may exhibit varying degrees of psychiatric symptoms that are detrimental to maternal and fetal health. 67

Mother/baby separation may impede early bonding as well as establishment of lactation. 68 These factors will inevitably cause additional stress for mothers in the postpartum period.

Healthcare providers should pay attention to a patient's mental health, including promptly assessing her sleep patterns and sources of anxiety, depression, and even suicidal ideation. A perinatal psychiatrist should be consulted when necessary.

12. General Precautions

Currently, there are no effective drugs or vaccines to prevent COVID‐19. Therefore, personal protection should be considered to minimize the risk of contracting the virus. 69

12.1. Patients and healthcare providers

Maintain good personal hygiene: consciously avoid close contact with others during the COVID‐19 pandemic period; reduce participation in any gathering in which a distance of at least 2 meters or 6 feet between individuals cannot be maintained; pay attention to hand washing and use hand sanitizer (60%–95% alcohol concentration) frequently. 70

Wearing a three‐ply surgical mask when visiting a hospital or other high‐risk area is recommended.

Seek medical assistance promptly for timely diagnosis and treatment when experiencing symptoms such as fever and cough.

12.2. Healthcare providers

Consider providing educational information (brochures, posters) in waiting areas.

Set up triage plans for screening. In units in which triage areas have been set up, staff should have appropriate PPE and ensure strict compliance with hand hygiene.

All pregnant patients who present to the hospital and for outpatient visits should be assessed and screened for symptoms and exposure relevant to COVID‐19.

Pregnant patients with known exposure relevant to COVID‐19 and those with mild or asymptomatic COVID‐19 infection should delay an antenatal visit by 14 days.

Reduce the number of visitors to the department.

On presentation to triage areas, pregnant patients who are symptomatic and/or with known exposure relevant to COVID‐19 should be placed in an isolation room for further assessment.

Medical staff who are caring for patients with suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 should be monitored closely for fever or other signs of infection and should not be working if they have any COVID‐19 symptoms. Common symptoms at onset of illness include fever, dry cough, myalgia, fatigue, and dyspnea. Medical staff assigned to care for patients with suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 should ideally minimize contact with other patients and colleagues, with the aim of reducing the risk of exposure and potential transmission.

Medical staff who have been exposed unexpectedly without appropriate PPE to a COVID‐19‐infected pregnant patient should be quarantined or self‐isolate for 14 days.

Pregnant healthcare professionals should follow risk‐assessment and infection‐control guidelines following exposure to patients with suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19.

13. Management of Biohazardous Material

Preventive measures associated with biohazardous exposures include 71 , 72 , 73 :

Use of single patient disposal supplies and equipment.

Needleless systems.

Proper hand hygiene.

Standard and special transmission precautions.

Red biohazardous waste containers and bags.

Appropriate use of PPE.

Use of a neutral zone in surgical areas and other areas where invasive procedures are performed.

Safe disposal of sharps not only in healthcare facilities but also in a woman's home and their community.2

Protocols that address non‐sharp biohazardous material management with waste segregation and storage in clearly labeled, leak proof, puncture‐resistant secondary containers, followed by collection that provides sterilization by autoclaving, incineration, interment, disinfection/encapsulation methods, energy‐based technologies, or collection by an emergency environmental and biosafety service.

14. Key Points for Consideration

Pregnant women with confirmed COVID‐19 infection should be managed by designated tertiary hospitals and should be counseled on the risk of adverse pregnancy outcome.

Negative pressure isolation rooms should be set up for safe labor and delivery and neonatal care. This may not be possible in many low‐resource settings but all possible attempts should be made for isolation and infection control.

During the COVID‐19 pandemic period, a detailed history regarding exposure relevant to COVID‐19 and clinical manifestations should be acquired routinely from all pregnant women attending for routine care.

Chest CT scan should be included in the work‐up of pregnant women with suspected/probable/confirmed COVID‐19 infection.

Suspected/probable cases should be treated in isolation and confirmed cases should be managed in a negative pressure isolation room. A woman with confirmed infection who is critically ill should be admitted to a negative pressure isolation room in the ICU.

Antenatal examination and delivery of pregnant women infected with COVID‐19 should be carried out in a negative pressure isolation room on the labor ward. Human traffic around this room should be limited when it is occupied by an infected patient.

All medical staff involved in management of infected women should wear appropriate PPE as required.

Management of COVID‐19‐infected pregnant women should be undertaken by a multidisciplinary team (obstetricians, maternal–fetal medicine subspecialists, intensivists, obstetric anesthetists, internal medicine or respiratory physicians, midwives, virologists, microbiologists, neonatologists, infectious disease specialists).

Timing and mode of delivery should be individualized, dependent mainly on the clinical status of the patient, gestational age, and fetal condition.

At present, limited data suggest that there is no evidence of vertical mother‐to‐baby transmission in women who develop COVID‐19 infection in late pregnancy.

There is currently insufficient evidence regarding the safety of breastfeeding and the need for mother/baby separation. If the mother is severely or critically ill, separation appears the best option, with attempts to express breastmilk to maintain milk production. If the patient is asymptomatic or mildly affected, breastfeeding and colocation (rooming‐in) can be considered by the mother in coordination with healthcare providers.

Healthcare professionals engaged in obstetric care should be trained and fitted appropriately for respirators.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mary Ann Lumsden, FIGO Chief Executive, Jeanne Conry, FIGO President Elect, and Hani Fawzi, FIGO Director of Projects, for their comments and advice on this paper.

References

- 1. Su S, Wong G, Shi W, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2016;24:490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ksiazek TG, Erdman D, Goldsmith CS, et al. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization . Summary of probable SARS cases with onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. https://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table 2004_04_21/en/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 5. World Health Organization . Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV). 2019. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ . Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 6. Wong SF, Chow KM, Leung TN, et al. Pregnancy and perinatal outcomes of women with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:292–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, et al. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS‐CoV‐2 as compared with SARS‐CoV‐1. N Engl J Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. World Health Organization . Report of the WHO‐China Joint Mission on Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19). 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/who-china-joint-mission-on-covid-19-final-report.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2020.

- 10. World Health Organization . WHO Director‐General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID‐19. 2020. [website]. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—3-march-2020. Accessed March 7, 2020.

- 11. Wu JT, Leung K, Bushman M, et al. Estimating clinical severity of COVID‐19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nat Med. 2020. 10.1038/s41591-020-0822-7. Accessed March 25, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yang J, Zheng Y, Gou X, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in the novel Wuhan coronavirus (COVID‐19) infection: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID‐19: Results of an open‐label non‐randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cao B, Wang Y, Wen D, et al. A trial of lopinavir–ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siston AM, Rasmussen SA, Honein MA, et al. ; Pandemic H1N1 Influenza in Pregnancy Working Group. Pandemic 2009 influenza A(H1N1) virus illness among pregnant women in the United States. JAMA. 2010;303:1517–1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alfaraj SH, Al‐Tawfiq JA, Memish ZA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS‐CoV) infection during pregnancy: Report of two cases & review of the literature. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2019;52:501–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen H, Guo J, Wang C, et al. Clinical characteristics and intrauterine vertical transmission potential of COVID‐19 infection in nine pregnant women: A retrospective review of medical records. Lancet. 2020;395:809–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhu H, Wang L, Fang C, et al. Clinical analysis of 10 neonates born to mothers with 2019‐nCov pneumonia. Transl Pediatr. 2020;9:51–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y, Chen H, Tang K, Guo Y. Clinical manifestations and outcome of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection during pregnancy. J Infect. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang L, Jiang Y, Wei M, et al. Analysis of the pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with COVID‐19 in Hubei Province [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2020;55:E009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lei DWC, Li C, Fang C, et al. Clinical characteristics of pregnancy with the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) infection. Chin J Perinatal Med. 2020;23:159–165. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shaw GM, Todoroff K, Velie EM, Lammer EJ. Maternal illness, including fever and medication use as risk factors for neural tube defects. Teratology. 1998;57:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oster ME, Riehle‐Colarusso T, Alverson CJ, Correa A. Associations between maternal fever and influenza and congenital heart defects. J Pediatr. 2011;158:990–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abe K, Honein MA, Moore CA. Maternal febrile illnesses, medication use, and the risk of congenital renal anomalies. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2003;67:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sass L, Urhoj SK, Kjærgaard J, Dreier JW, Strandberg‐Larsen K, Nybo Andersen AM. Fever in pregnancy and the risk of congenital malformations: A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Madinger NE, Greenspoon JS, Ellrodt AG. Pneumonia during pregnancy: Has modern technology improved maternal and fetal outcome? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:657–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen YH, Keller J, Wang IT, Lin CC, Lin HC. Pneumonia and pregnancy outcomes: A nationwide population‐based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(288):e1–e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schwartz DA. An analysis of 38 pregnant women with COVID‐19, their newborn infants, and maternal‐fetal transmission of SARS‐CoV‐2: Maternal coronavirus infections and pregnancy outcomes. Arch Pathol Lab Med. In‐Press; 10.5858/arpa.2020-0901-sa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Poon LC, Shennan A, Hyett JA, et al. The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) initiative on pre‐eclampsia: A pragmatic guide for first‐trimester screening and prevention. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2019;145(Suppl 1):1‐33. 10.1002/ijgo.12802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization . Global surveillance for COVID‐19 caused by human infection with COVID‐19 virus. Interim guidance, https://www.who.int/publications-detail/global-surveillance-for-human-infection-with-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov). Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 34. World Health Organization . Rational use of protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Interim guidance. 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 35. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 36. Li X, Xia L. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Role of chest CT in diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–7 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhao W, Zhong Z, Xie X, Yu Q, Liu J. Relation between chest CT findings and clinical conditions of coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) pneumonia: A multicenter study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020:1–6 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, et al. Correlation of chest CT and RT‐PCR testing in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in China: A report of 1014 cases. Radiology. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patel SJ, Reede DL, Katz DS, Subramaniam R, Amorosa JK. Imaging the pregnant patient for nonobstetric conditions: Algorithms and radiation dose considerations. Radiographics. 2007;27:1705–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. National Library of Medicine . Gadopentetate. In: Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501398/. Accessed March 7, 2020.

- 41. Miller RW. Discussion: Severe mental retardation and cancer among atomic bomb survivors exposed in utero. Teratology. 1999;59:234–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Committee on Obstetric Practice . Committee Opinion No. 723: Guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e210–e216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. American College of Radiology . ACR‐SPR practice parameter for imaging pregnant or potentially pregnant adolescents and women with ionizing radiation. 2018. https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/Practice-Parameters/Pregnant-Pts.pdf. Accessed March 10, 2020.

- 44. Tremblay E, Thérasse E, Thomassin‐Naggara I, et al. Quality initiatives: Guidelines for use of medical imaging during pregnancy and lactation. Radiographics. 2012;32:897–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Emerging understandings of 2019‐nCoV. Lancet. 2020;395:311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maxwell C, McGeer A, Tai KFY, Sermer M. No 225‐Management guidelines for obstetric patients and neonates born to mothers with suspected or probable severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:e130–e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim Clinical Guidance for Management of Patients with Confirmed Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 48. World Health Organization [Twitter]. 2020. https://twitter.com/WHO/status/1240409217997189128/photo/1.

- 49. Boseley S. China trials anti‐HIV drug on coronavirus patients. The Guardian. 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/07/china-trials-anti-hiv-drug-coronavirus-patients. Accessed March 7, 2020.

- 50. National Institutes of Health . NIH clinical trial of remdesivir to treat COVID‐19 begins. 2020. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/nih-clinical-trial-remdesivir-treat-covid-19-begins. Accessed March 9, 2020.

- 51. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community‐acquired pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Rasmussen SA, Smulian JC, Lednicky JA, Wen TS, Jamieson DJ. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) and pregnancy: What obstetricians need to know. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Røsjø H, Varpula M, Hagve TA, et al. Circulating high sensitivity troponin T in severe sepsis and septic shock: Distribution, associated factors, and relation to outcome. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bhatia PK, Biyani G, Mohammed S, Sethi P, Bihani P. Acute respiratory failure and mechanical ventilation in pregnant patient: A narrative review of literature. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2016;32:431–439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. World Health Organization . Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when COVID‐19 is suspected. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected. Accessed March 15, 2020.

- 56. Boelig RC, Saccone G, Bellussi F, Berghella V. MFM guidance for COVID‐19. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shek CC, Ng PC, Fung GP, et al. Infants born to mothers with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Pediatrics. 2003;112:e254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Qi H, Chen D, Feng L, Zou L, Li J. Obstetric considerations on delivery issues for pregnant women with COVID‐19 infection. Chin J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;55:E001–E001. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang H, Wang C, Poon LC. Novel coronavirus infection and pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Favre G, Pomar L, Qi X, Nielsen‐Saines K, Musso D, Baud D. Guidelines for pregnant women with suspected SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology . Interim Considerations for Obstetric Anesthesia Care Related to Covid‐19. https://soap.org/education/provider-education/expert-summaries/interim-considerations-for-obstetric-anesthesia-care-related-to-covid19/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 62. Rodrigo C, Leonardi‐Bee J, Nguyen‐Van‐Tam J, Lim WS. Corticosteroids as adjunctive therapy in the treatment of influenza. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD010406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Mullins E, Evans D, Viner R, O'Brien P, Morris E. Coronavirus in pregnancy and delivery: Rapid review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) and breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/maternal-or-infant-illnesses/covid-19-and-breastfeeding.html. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 65. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Interim Considerations for Infection Prevention and Control of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Inpatient Obstetric Healthcare Settings. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/inpatient-obstetric-healthcare-guidance.html#anchor_1582067966715. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 66. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Practice Advisory: Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID‐19). https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Practice-Advisories/Practice-Advisory-Novel-Coronavirus2019?IsMobileSet=false. Accessed March 8, 2020.

- 67. Dørheim SK, Bjorvatn B, Eberhard‐Gran M. Insomnia and depressive symptoms in late pregnancy: A population‐based study. Behav Sleep Med. 2012;10:152–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chua M, Lee J, Sulaiman S, Tan HK. From the frontlines of COVID‐19 – How prepared are we as obstetricians: A commentary. BJOG. 2020; [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maternal and Fetal Experts Committee, Chinese Physician Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Obstetric Subgroup, Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chinese Medical Association; Society of Perinatal Medicine, Chinese Medical Association; Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Perinatal Medicine . Proposed management of COVID‐19 during pregnancy and puerperium. Chin J Perinatal Med. 2020;23:73–79. [Google Scholar]

- 70. World Health Organization . Infection prevention and control during health care when novel coronavirus (nCoV) infection is suspected. Interim guidance. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/infection-prevention-and-control-during-health-care-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected-20200125. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 71. Registered Nursing . Handling hazardous and infectious materials: NCLEX‐RN [website]. 2020. https://www.registerednursing.org/nclex/handling-hazardous-infectious-materials/. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 72. Vanderbilt University Medical Center . Environmental health and safety. Biohazardous waste: segregation, collection and disposal guide[website]. https://www.vumc.org/safety/waste/biological-waste-guide. Accessed March 25, 2020.

- 73. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Infection Control. 3. Management of regulated medical waste in health‐care facilities. 2015. https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/environmental/background/medical-waste.html#i3. Accessed March 25, 2020.