Abstract

Background

Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) is a vital regulator of mammalian expression. Despite multiple pieces of evidence indicating that dysregulation of RUNX1 is a common phenomenon in human cancers, there is no evidence from pan-cancer analysis.

Methods

We comprehensively investigated the effect of RUNX1 expression on tumor prognosis across human malignancies by analyzing multiple cancer-related databases, including Gent2, Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER), Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA), the Human Protein Atlas (HPA), UALCAN, PrognoScan, cBioPortal, STRING, and Metascape.

Results

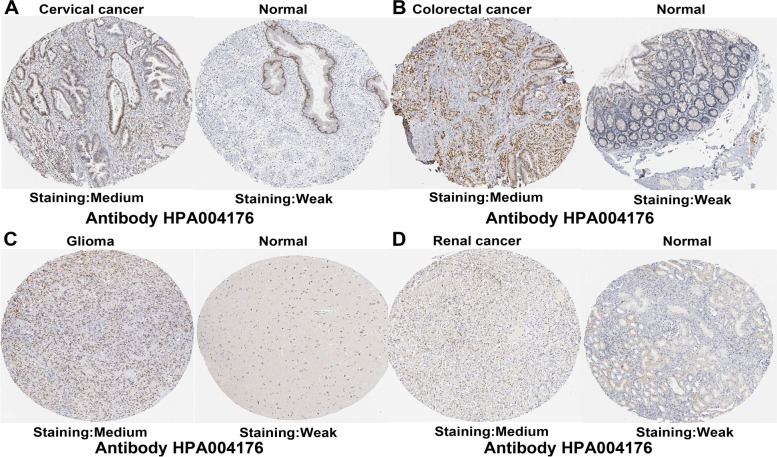

Bioinformatics data indicated that RUNX1 was overexpressed in most of these human malignancies and was significantly associated with the prognosis of patients with cancer. Immunohistochemical results showed that most cancer tissues were moderately positive for granular cytoplasm, and RUNX1 was expressed at a medium level in four types of tumors, including cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, glioma, and renal cancer. RUNX1 expression was positively correlated with infiltrating levels of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in 33 different cancers. Moreover, RUNX1 expression may influence patient prognosis by activating oncogenic signaling pathways in human cancers.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that RUNX1 expression correlates with patient outcomes and immune infiltrate levels of CAFs in multiple tumors. Additionally, the increased level of RUNX1 was linked to the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways in human cancers, suggesting a potential role of RUNX1 among cancer therapeutic targets. These findings suggest that RUNX1 can function as a potential prognostic biomarker and reflect the levels of immune infiltrates of CAFs in human cancers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12885-022-09632-y.

Keywords: RUNX1, Prognostic biomarker, TCGA, Cancer-associated fibroblasts

Background

Despite great advances in the rapid diagnosis and treatment of tumors, cancer remains a major cause of death [1]. Given the increased morbidity and mortality among patients with cancer, it is necessary to further understand the pathogenesis of this disease to improve patient outcomes. Using the analysis of public data from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project and the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [2, 3], we can now understand the function of certain genes in human cancer.

Runt-related transcription factors (RUNXs) are involved in the regulation of several biological processes in mammals. For example, RUNX family members RUNX1, 2, and 3 play important roles in skeletal development, while the transcription factor RUNX2 is required for osteoblast differentiation and chondrocyte maturation [4]. RUNX family members bind to the same non-DNA-binding core binding factor-beta (CBF-β) subunit to form a heterodimer, but they exhibit distinct expression patterns [5]. RUNX1 is widely expressed in mammalian cells and is reported to be dysregulated in many human cancers [4, 6]. Overexpression of RUNX1 has also been observed in hepatocellular carcinoma [7] and gastric cancer [8]. Interestingly, RUNX1 promotes the development of ovarian and skin cancers [9, 10], but exhibits tumor-suppressive activity in lung and prostate cancers [11, 12]. RUNX1 mutations are closely related to tumorigenesis in leukemia [13] and breast cancer [14]. Moreover, it has been reported that RUNX1 phosphorylation involves in osteolytic bone destruction in ERα-positive breast cancer [15]. However, whether RUNX1 is involved in the pathogenesis of multiple tumors through a common signaling pathway remains unclear.

In our study, we systematically explored the effect of RUNX1 expression on the prognosis associated with several human cancers. Our findings indicate that RUNX1 expression is increased in various tumors, and thus may be linked to tumor progression and patient prognosis. Moreover, RUNX1 expression levels can reflect the infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in tumor tissues.

Methods

Data collection and processing

We first studied the expression levels of the RUNX1 in human cancer using the Gent2 database (http://gent2.appex.kr/gent2/), TIMER database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/), UALCAN database (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu), Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), and Human protein atlas (HPA, https://www.proteinatlas.org). Subsequently, we evaluated the prognostic role of RUNX1 in cancer patients by using the PrognoScan database (http://gibk21.bse.kyutech.ac.jp/PrognoScan/index.html) and the GEPIA database. Next, we selected the “TCGA Pan Cancer Atlas Studies” in the cBioPortal web (https://www.cbioportal.org/) for analysis of the genetic alteration characteristics of RUNX1 in human cancer. The immunological role of RUNX1 was analyzed using the TIMER database. Finally, we analyzed the co-expression genes of RUNX1 in the STRING (https://string-db.org/) database, and the related functional predictions between RUNX1 and their co-expressed genes in the Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG, https://www.genome.jp/kegg/), gene ontology (GO, http://geneontology.org/) and Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html).

Gent2 database analysis

The Gent2 database (http://gent2.appex.kr/gent2/), an online cancer microarray database, was used to analyze the transcriptional expression of RUNX1 in different human cancers [16].

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER) database analysis

The TIMER database (https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) can be used to analyze the correlation between gene expression and the level of immune cell infiltration in various human cancers [17]. The “Diffexp module” was used in this study to evaluate the RUNX1 expression across human cancers. Next, a correlation analysis was performed between RUNX1 expression and infiltrating levels of CD8 + T cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in different types of tumors both by “gene modules” and “outcome modules”.

Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database analysis

The HPA project (https://www.proteinatlas.org) includes information on the distribution of more than 24,000 human proteins in tissues and cells [18]. Thus, we searched the HPA website to analyze RUNX1 protein expression in both human cancer and normal tissues. Immunostaining intensity and patient information corresponding to the different cancer types are available on this website.

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) database analysis

The GEPIA website (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/) has extensive gene expression data from TCGA and the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases [19]. In this study, we analyzed RUNX1 expression in human cancers by "Expression on Box Plots" mode, and then used the "Expression on Box Plots" and "Survival Plots" to analyze the correlation between RUNX1 expression and tumor stage and prognosis across human cancers, including overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS).

UALCAN database analysis

The UALCAN database (http://ualcan.path.uab.edu) provides publicly available data from TCGA [20]. In this study, TCGA analysis was conducted to investigate DNA methylation of the RUNX1 promoter in different types of cancer.

PrognoScan database survival analysis

The PrognoScan database (http://gibk21.bse.kyutech.ac.jp/PrognoScan/index.html) was used to analyze the relationship between RUNX1 expression and clinical outcomes [21]. In this study, we selected all cancer types and a P-value < 0.05 as the threshold.

The cBioPortal database analysis

The cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org) has been used to analyze the information on genetic alterations in various cancer genomic datasets [22]. In our study, we analyzed the alteration frequency of RUNX1 in different cancers based on data from “TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas Studies,” and summarized mutated site information of the RUNX1 gene. We obtained the alteration frequency and the information on genetic mutations of the RUNX1 gene across human cancers using the “Cancer Type Summary” and “Mutations” modes, respectively.

STRING database analysis

The STRING database (https://string-db.org/cgi/input?sessionId=bL2ZI4D088fF) is used to model protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks [23]. In our study, the PPI network of the RUNX1 protein was visualized using the following filters: “full STRING network,” “evidence,” “experiments,” “low confidence (0.150),” and “no more than 50 interactors” in the 1st shell.

Metascape database analysis

The Metascape database (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html) is a publicly available website for functional gene analysis [24]. Enriched analyses of RUNX1 and its neighboring genes were performed using Metascape to investigate the possible functional mechanisms of RUNX1, including Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses [25]. These terms were considered significant, with a P-value < 0.01, count > 3, and enrichment factor > 1.5. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses of all data were performed using the statistical software from all online databases. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Transcriptional levels of RUNX1 in the pan-cancer analysis

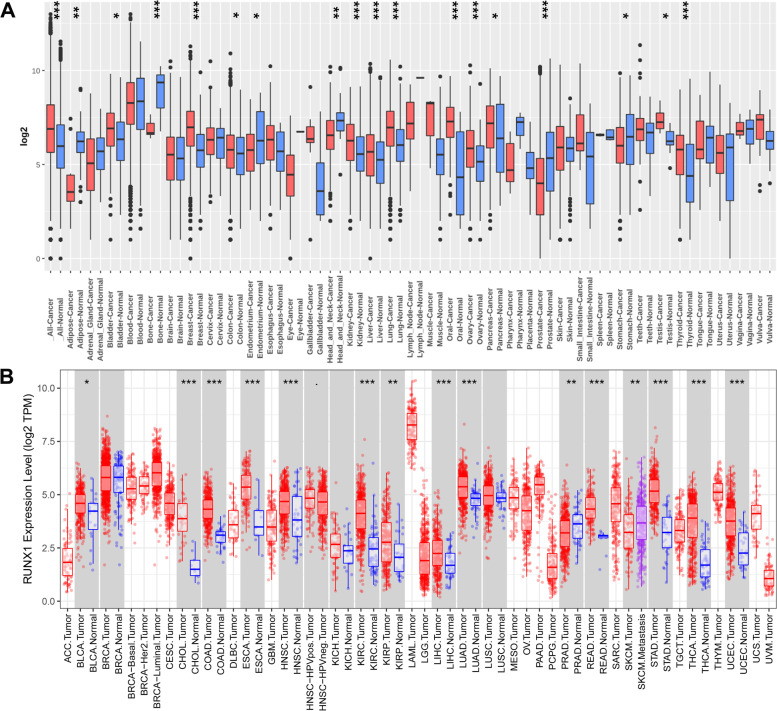

We first analyzed the mRNA expression levels of RUNX1 across human cancers and paired normal samples by utilizing the HG-U133 microarray (GPL570 platform) of the Gent2 database (Fig. 1A). Compared with normal samples, RUNX1 was upregulated in a variety of tumors, including bladder cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, kidney cancer, liver cancer, lung cancer, oral cancer, ovary cancer, pancreatic cancer, testis cancer, and thyroid cancer (all P < 0.05). Meanwhile, RUNX1 expression was decreased in multiple datasets, including adipose cancer, bone cancer, endometrium cancer, head and neck cancer, prostate cancer, and stomach cancer (all P < 0.05). Second, we verified the differences in RUNX1 expression using the TIMER database. As shown in Fig. 1B, compared to normal samples, overexpression of RUNX1 was observed in 17 pathological types of tumors, including bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma (CESC), cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma (KIRP), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), rectum adenocarcinoma (READ), stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD), thyroid carcinoma (THCA), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC); however, RUNX1 expression was reduced in prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) (all P < 0.05). Third, we supplemented the normal tissue expression data from the GTEx dataset as a control group and retrieved the mRNA expression status of RUNX1 in human tumors using the GEPIA website (Fig. S1). The results showed that RUNX1 expression was higher in CESC, COAD, ESCA, GBM, KIRC, acute myeloid leukemia (AML), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), READ, STAD, thymoma (THYM), UCEC, and uterine carcinosarcoma (UCS) than in adjacent normal tissue samples (all P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). However, no statistical differences were found for other tumors. Finally, we assessed the protein levels of RUNX1 in the tissues based on the results from the HPA database (Fig. S2A-B) and found that most of the cancer tissues were moderately positive for granular cytoplasm.

Fig. 1.

RUNX1 expression analysis in pan-cancer. A. Increased or decreased RUNX1 in datasets of different cancers compared with normal tissues in the Gent2 database; B. RUNX1 expression profile across all tumor samples and paired normal tissues determined by TIMER database. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01; *** P < 0.001

Fig. 2.

Correlation between RUNX1 expression and clinicopathological parameters in human cancers (GEPIA database). A. The expression of RUNX1 in different cancer tissues and normal tissues; B. Correlation between RUNX1 expression and tumor stage in different human cancers. *Indicate that the results are statistically significant

Associations between the mRNA levels of RUNX1 and clinicopathological parameters across human cancers

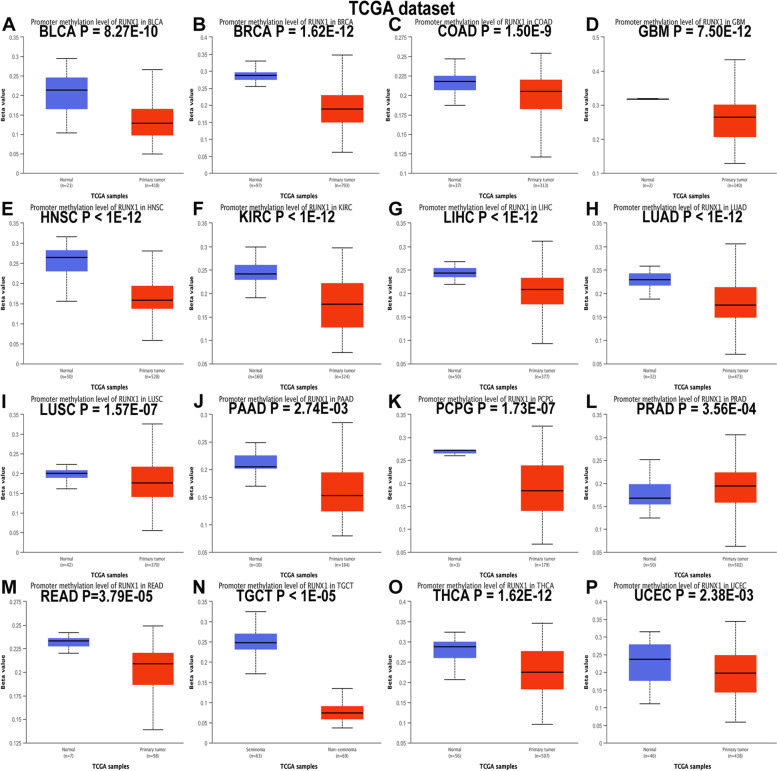

We analyzed RUNX1 expression in tumors at different stages using the GEPIA website (Fig. 2B). The expression levels of RUNX1 varied significantly in Breast invasive carcinoma(BRCA), KIRC, PAAD, THCA, and UCEC (all P < 0.05). Next, we used the UALCAN database to explore the correlation between RUNX1 expression levels and promoter methylation in human cancers. The results suggested that the promoter region of RUNX1 exhibited hypomethylation in a variety of tumors, including BLCA, BRCA, COAD, GBM, HNSC, KIRC, LIHC, LUAD, lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), PAAD, pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), READ, testicular germ cell tumors (TGCT), THCA, and UCEC, but hypermethylation in PRAD (Fig. 3A-P; all P < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

RUNX1 promoter methylation analysis in pan-cancer based on UALCAN database. A-P.The promoter methylation of RUNX1 in bladder urothelial carcinoma (BLCA), breast invasive carcinoma (BRCA), colon adenocarcinoma (COAD), glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSC), kidney renal clear cell carcinoma (KIRC), liver hepatocellular carcinoma (LIHC), lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), lung squamous cell carcinoma (LUSC), pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD), pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma (PCPG), prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD), rectal adenocarcinoma (READ), testis germ cell tumor (TGCT), thyroid carcinoma (THCA), and uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (UCEC)

RUNX1 prognosis analysis in different human cancers

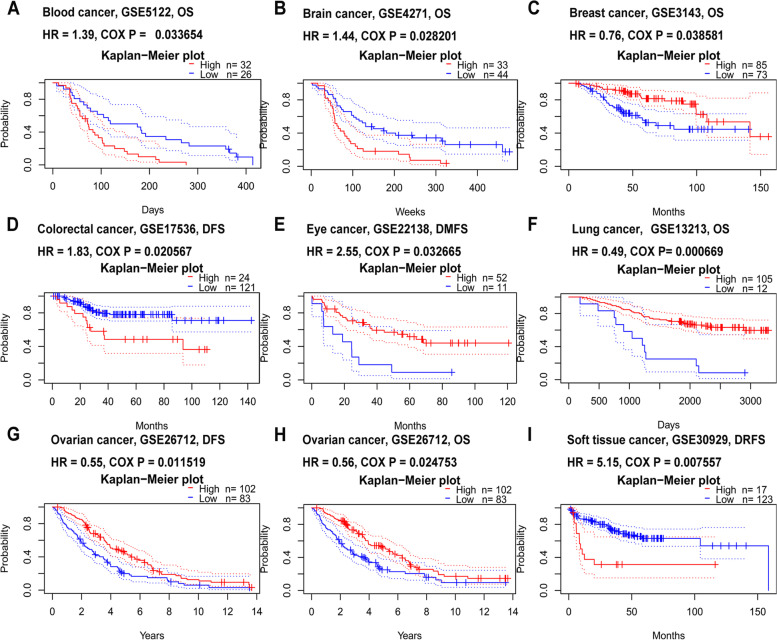

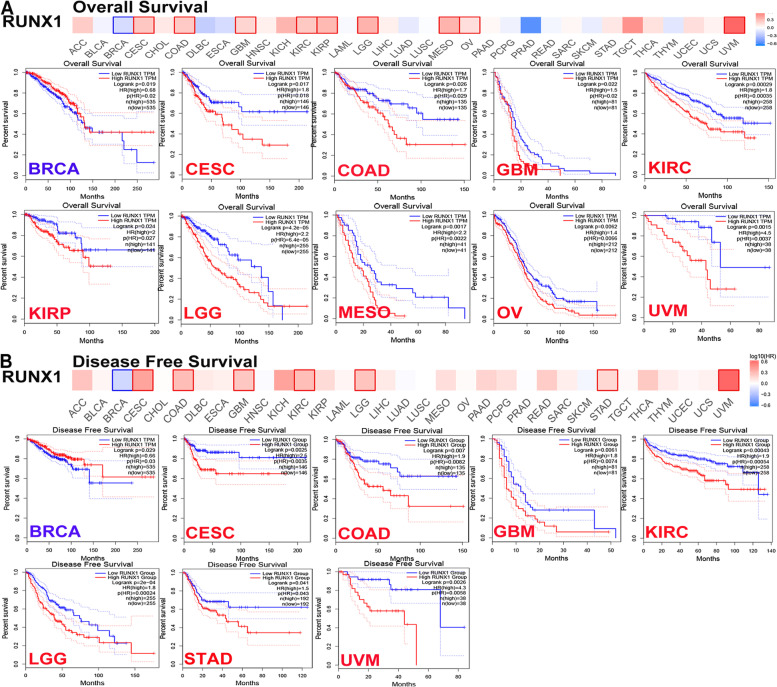

To assess the prognostic role of RUNX1 in patients with cancer, we conducted a prognosis analysis across human cancers using PrognoScan and GEPIA. First, we observed a correlation between RUNX1 expression and prognosis in 8 of the 13 types of cancer using the PrognoScan database (Table S1; Fig. 4A-I). Our results suggest that RUNX1 expression plays a detrimental role in four cancer types, including blood, brain, colorectal, and soft tissue cancers. However, they also suggest that RUNX1 plays a protective role in four other cancers, including breast, eye, lung, and ovarian cancers. Second, we studied the role of RUNX1 in human cancers using GEPIA (Table S2; Fig. 5A-B). Notably, RUNX1 had a negative overall effect on cancer (OS: total log-rank P = 0, HR = 1.4; DFS: total log-rank P = 0.29, HR = 0.96). High RUNX1 expression levels were linked to worse OS and DFS in CESC, COAD, GBM, KIRC, brain lower-grade glioma (LGG), and uveal melanoma (UVM), but were related to better OS and DFS in BRCA. Meanwhile, mesothelioma (MESO), ovarian cancer (OV), and STAD outcomes were found to have a negative correlation with RUNX1 expression. However, RUNX1 expression has no significant effect on the prognosis of other cancers.

Fig. 4.

The prognostic values of RUNX1 in different human cancers by PrognoScan database. A. Overall survival (OS) curve of blood cancer; B. Overall survival (OS) curve of brain cancer; C. Overall survival (OS) curve of breast cancer; D. Disease free survival (DFS) curve of colorectal cancer; E. Distant metastasis free survival (DMFS) curve of eye cancer; F. Overall survival (OS) curve of lung cancer; G. and H. Disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) curve of ovarian cancer; I. Distant recurrence free survival (DRFS) curve of soft tissue cancer

Fig. 5.

The prognostic value of RUNX1 in different human cancers by GEPIA database. A. Overall survival analysis of RUNX1 expression in different tumors; B. Disease-free survival analysis of RUNX1 expression in different tumors

Based on the expression and prognosis results from the GEPIA database, RUNX1 may act as a potential prognostic biomarker for patients with cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, glioma, and renal cancer. Thus, we further verified RUNX1 protein expression in these cancers by immunohistochemistry, using the HPA database. The results showed that RUNX1 was expressed at a moderate level in tumor tissues, but very weak RUNX1 staining was detected in any normal tissue (Fig. 6A-D).

Fig. 6.

RUNX1 protein expression was detected by immunohistochemistry from the HPA database. A. The expression of RUNX1 protein in cervical cancer and normal sample; B. The expression of RUNX1 protein in colorectal cancer and normal sample; C. The expression of RUNX1 protein in glioma and normal sample; D. The expression of RUNX1 protein in renal cancer and normal sample

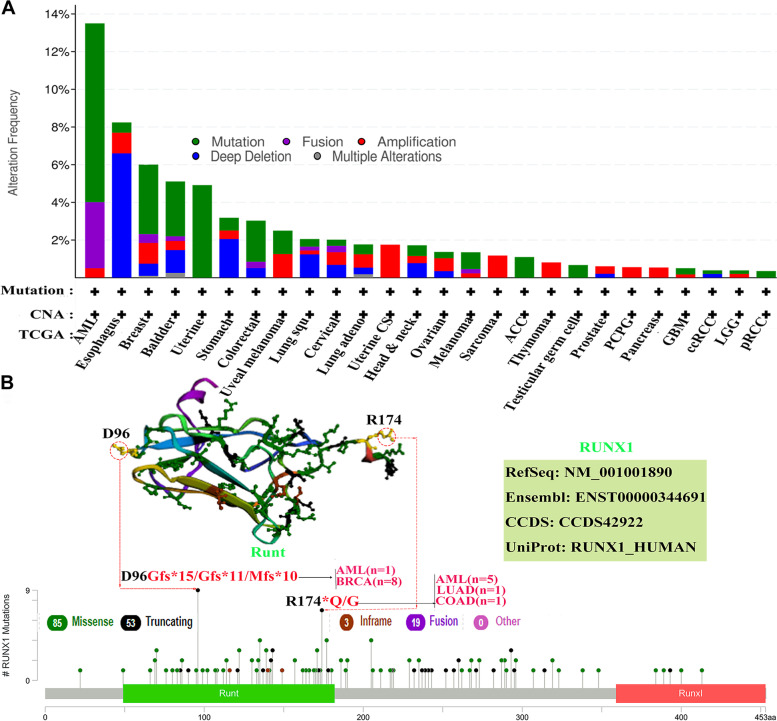

RUNX1 genetic alteration frequency analysis across human cancers

We searched the cBioPortal database to analyze the alteration frequency of the RUNX1 gene in different cancers based on TCGA pan-cancer analyses. As shown in Fig. 7A, one or more alterations were detected in 33 types of human cancers, and 9.5% (19 cases) of patients with AML (200 cases) were observed to have mutations in RUNX1, representing the highest frequency among all patients with cancer. In addition, deep deletion of RUNX1 occurred in 6.59% (12 cases) of patients with ESCA (182 cases), and mutations in RUNX1 were the primary alteration type in 4.91% (26 cases) of patients with uterine cancer (529 cases). Subsequently, we queried the information of the genetic alterations of RUNX1 in the pan-cancer analysis, including the type, site, and case number of each genetic alteration, in the cBioPortal database (Fig. 7B). The results indicated that RUNX1 “Missense” mutation was the most common type of alteration among all. In addition, D96Gfs*15/Gfs*11/Mfs*10 alterations were observed in the Runt domain of RUNX1 in one case of AML and eight cases of BRCA. Whereas the R174*Q/G alteration in the Runt domain was observed in five cases of AML, one case of LUAD, and one case of COAD.

Fig. 7.

Mutation feature of RUNX1 in different tumors (cBioPortal database). A. The alteration frequency of RUNX1 with mutation type in human cancers based cBioPortal database; B.The mutation site with the highest alteration frequency (D96Gfs*15/Gfs*11/Mfs*10 and R174*Q/G) in the 3D structure of RUNX1

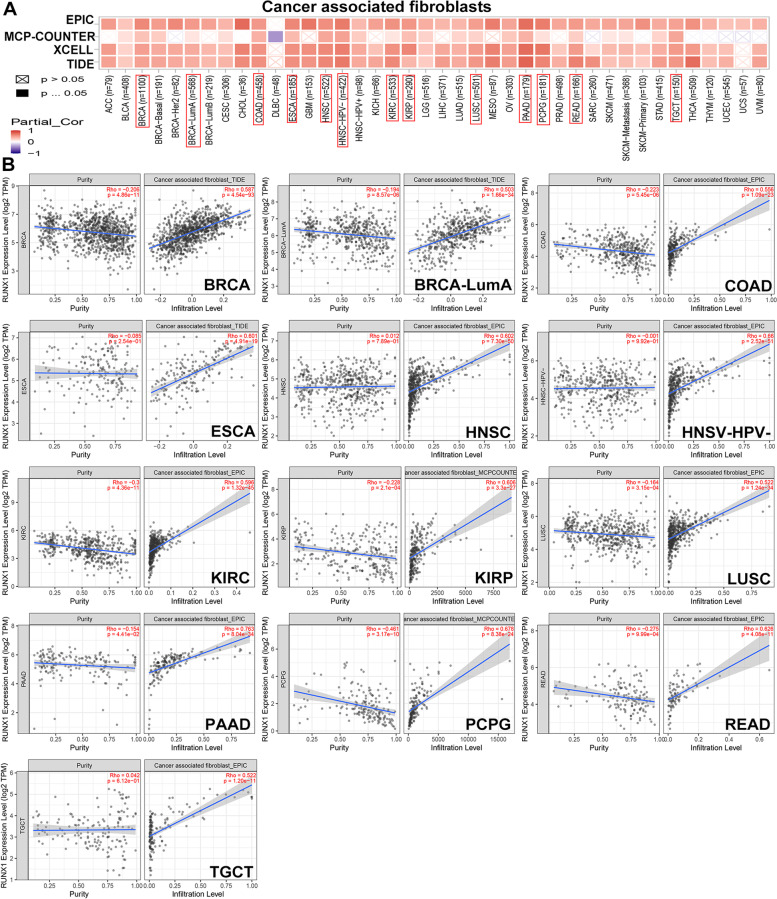

Correlation analysis between RUNX1 expression and immune cells infiltration levels in diverse cancer types

In our study, we first analyzed the association between immune infiltration and RUNX1 expression in human cancers using TIMER 2.0. According to most algorithms, the infiltration level of CD8 + T cell was significantly negatively or positively associated with RUNX1 expression in all three tested tumors, including BRCA-Her2 (Rho = -0.379, P = 1.03e-03), lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBC) (Rho = 0.532, P = 3.46e-4), and UVM (Rho = 0.665, P = 1.04e-10) (Fig. S3A-B). We also observed a significant positive correlation between CAFs infiltration and RUNX1 expression in 32 types of human cancer based on all algorithms (Fig. 8A-B).

Fig. 8.

Correlation analysis between RUNX1 expression and immune infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts in TIMER database. A. The heat map indicated the correlation between RUNX1 expression and immune infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts; B. The significantly positive correlations between RUNX1 expression and immune infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts were observed in 13 kinds of tumors (Rho > 0.5)

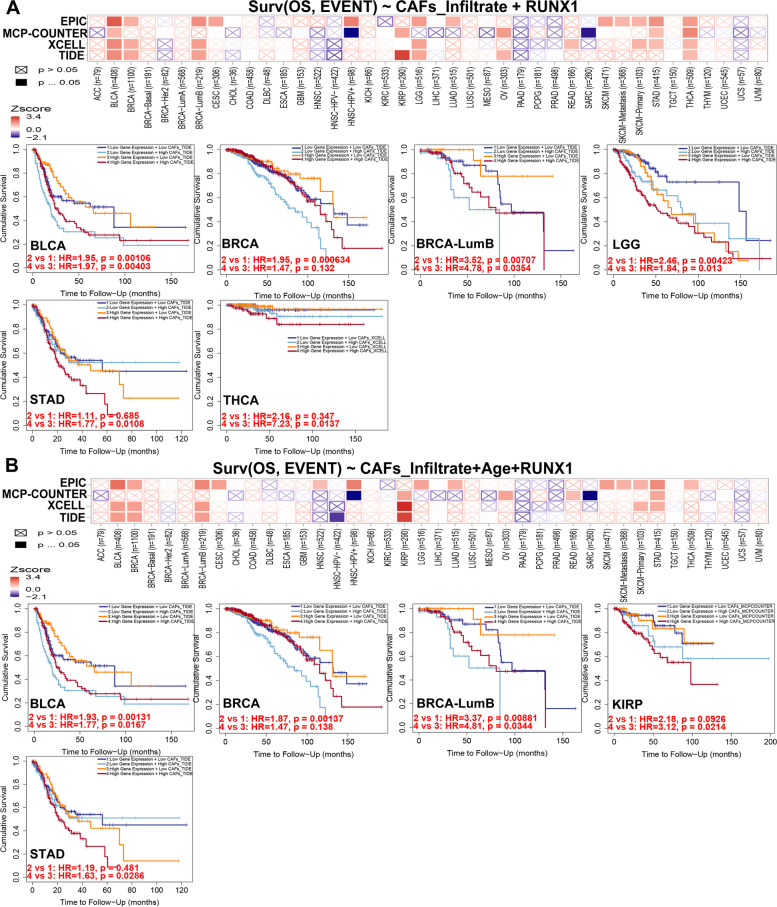

We used a Cox proportional hazard model to evaluate the effects of CAFs infiltration levels and RUNX1 expression on patient clinical outcomes in TIMER 2.0 database. CAFs infiltration was divided into low and high levels, and clinical factors and gene expression were selected as covariates. As shown in Fig. 9A, we revealed a prognostic correlation between RUNX1 expression and the infiltration of CAFs in various cancer types, according to most algorithms. RUNX1 may affect patient prognosis via immune infiltration of CAFs, including BLCA, BRCA, BRCA-LumB, LGG, STAD, and THCA. After adjusting for confounders (such as age, stage, sex, race, and tumor purity) in the regression model, we found a significant association between CAFs infiltration and RUNX1 expression in the prognosis of patients with cancer patients, such as BLCA, BRCA-LumB, CESC, LGG, READ, SARC (Table S3). The heat map and cumulative survival graphs for several cancers with statistical differences are displayed after adjusting for age factor (Fig. 9B). For example, as the age of cancer patients with high infiltration levels increases, the survival outcome is worse, including BLCA, BRCA, BRCA-LumB, KIRP, and STAD.

Fig. 9.

The prognostic signature built by the immune infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts and the expression of RUNX1 (TIMER database). A. The heat map and the survival curve indicated the correlation between RUNX1 experssion and infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts; B. The heat map and the survival curve indicated the correlation between the RUNX1 experssion and infiltration of cancer-associated fibroblasts by adjusting for confounders in the regression model

RUNX1-related gene enrichment analysis across human cancers

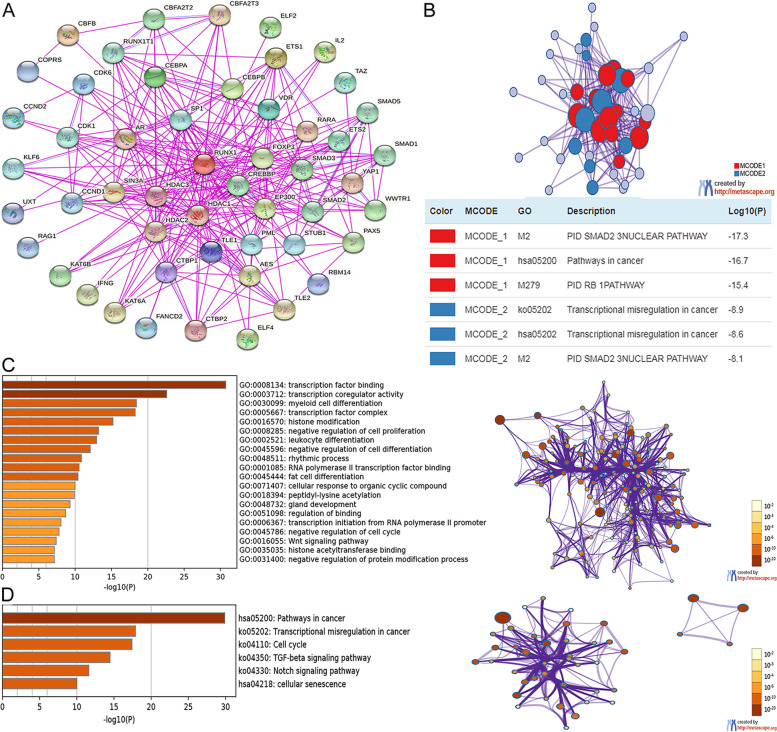

We conducted an enrichment analysis of RUNX1 and its neighboring genes using STRING and Metascape databases. First, we identified neighboring genes interacting with RUNX1 using the STRING website; the detailed results are shown in Fig. 10A. To better analyze the functional mechanism between RUNX1 expression and human cancers, we retrieved the Metascape database to construct a PPI enrichment analysis and obtained two of the most significant MCODE components from the analysis results (Fig. 10B).

Fig. 10.

The enrichment analysis of RUNX1 and neighboring genes in human cancer. A. Protein–protein interaction network of RUNX1 (STRING database); B. PPI network and two most significant MCODE components form the PPI network; C. Heat map of Gene Ontology (GO) enriched terms colored by p-values; D. Heat map of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enriched terms colored by p-values

Next, the potential functional mechanism of RUNX1 and its neighboring genes was predicted using the Metascape database. We obtained the results of GO and KEGG analyses: GO analysis included biological process ( 15 items), molecular function (4 items), and cellular component (1 item) (Fig. 10C and Table 1). The top six KEGG pathways of RUNX1 and its neighboring genes are shown in Fig. 10D and Table 2.

Table 1.

The Gene Ontology (GO) function enrichment analysis of RUNX1 and neighbor genes in pan-cancer (Metascape database)

| Category (GO) | Term ID | Description | Count | Log10(P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Functions | GO:0,008,134 | transcription factor binding | 25 | -30.724 |

| Molecular Functions | GO:0,003,712 | transcription coregulator activity | 20 | -22.598 |

| Biological Processe | GO:0,030,099 | myeloid cell differentiation | 16 | -18.438 |

| Cellular Components | GO:0,005,667 | transcription factor complex | 15 | -18.268 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,016,570 | histone modification | 15 | -15.205 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,008,285 | negative regulation of cell proliferation | 16 | -13.220 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,002,521 | leukocyte differentiation | 14 | -12.955 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,045,596 | negative regulation of cell differentiation | 15 | -12.086 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,048,511 | rhythmic process | 10 | -10.875 |

| Molecular Functions | GO:0,001,085 | RNA polymerase II transcription factor binding | 8 | -10.545 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,045,444 | fat cell differentiation | 9 | -10.396 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,071,407 | cellular response to organic cyclic compound | 11 | -9.988 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,018,394 | peptidyl-lysine acetylation | 8 | -9.890 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,048,732 | gland development | 10 | -9.297 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,051,098 | regulation of binding | 9 | -8.692 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,006,367 | transcription initiation from RNA polymerase II promoter | 7 | -8.054 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,045,786 | negative regulation of cell cycle | 10 | -7.792 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,016,055 | Wnt signaling pathway | 9 | -7.395 |

| Molecular Functions | GO:0,035,035 | histone acetyltransferase binding | 4 | -7.147 |

| Biological Processes | GO:0,031,400 | negative regulation of protein modification process | 10 | -7.145 |

Table 2.

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) function enrichment analysis of RUNX1 and neighbor genes in pan-cancer (Metascape database)

| Category | Term ID | Description | Count | Log10(P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KEGG Pathway | hsa05200 | Pathways in cancer | 20 | -29.897 |

| KEGG Pathway | ko05202 | Transcriptional misregulation in cancer | 13 | -17.899 |

| KEGG Pathway | ko04110 | Cell cycle | 10 | -17.428 |

| KEGG Pathway | ko04350 | TGF-beta signaling pathway | 8 | -14.481 |

| KEGG Pathway | ko04330 | Notch signaling pathway | 6 | -11.617 |

| KEGG Pathway | hsa04218 | cellular senescence | 7 | -10.015 |

Discussion

As previously reported, RUNX1 expression plays a dual role in different human cancers. Increased RUNX1 expression is strongly associated with HNSC, predicting tumor recurrence and patient prognosis [26]. Several studies have demonstrated that RUNX1 expression is closely associated with the progression of solid tumors, such as ovarian cancer [9], glioblastoma [27], and renal cancer [28]. In contrast, RUNX1 overexpression has been linked to favorable outcomes and monitored prognosis during therapy in neuroblastoma [29]. RUNX1 expression can predict a better outcome for patients with prostate cancer, but plays a dual role in promoting or inhibiting the progression of this cancer [12]. In summary, RUNX1 expression may have positive or negative effects on the clinical outcomes of different cancers. In our study, the mRNA expression of RUNX1 was upregulated in almost all human tumors, according to the GenT2, TIMER, and GEPIA databases. However, RUNX1 expression also decreased in several cancer datasets from the GenT2 database. Thus, these findings urged us to further understand the expression status of RUNX1 in human cancers and its effect on tumor prognosis based on pan-cancer analysis.

Our analysis indicated that RUNX1 had a detrimental effect on four cancer types, including blood, brain, colorectal, and soft tissue cancers. In contrast, RUNX1 played a protective role in four other cancers. However, RUNX1 was found to have a negative overall effect on cancer survival according to the GEPIA database. RUNX1 expression was markedly linked to the prognosis of 11 cancer types (including OS and DFS) and had a detrimental effect on the corresponding tumors. However, RUNX1 had a protective role in both OS and DFS in patients with BRCA. Combining the results of the two databases, we found that the role of RUNX1 in ovarian cancer was detrimental. These differences may be associated with differences in data processing and molecular functions. The datasets in the PrognoScan database were obtained from GEO data, and the GEPIA datasets included TCGA and GTEx data. Considering the heterogeneity of multiple databases, we analyzed the potential prognostic value of RUNX1 based on TCGA data. Our results showed that RUNX1 overexpression may be a prognostic biomarker in several cancers, including CESC, COAD, GBM, and KIRC. Interestingly, RUNX1 expression in COAD was higher than in normal samples, suggesting a poor prognosis in these patients, which seems to be inconsistent with the role of tumor suppressors in gastrointestinal malignancies. This may be related to the genomic instability and diverse molecular functions of RUNX1 in gastrointestinal adenocarcinoma [30]. Additionally, overexpression of RUNX1 resulted in significantly poorer clinical survival in patients with renal cancer [28]. These results confirm that RUNX1 is a potential biomarker for these tumors.

RUNX1 is essential for the maturation of lymphocytes and megakaryocytes in adults [4]. Moreover, downregulated expression of RUNX1 has been linked to the regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in lung cancer [31], whereas higher levels of RUNX1 can enhance the killing effect of natural killer cells in cervical cancer [32]. Furthermore, we observed that RUNX1 expression had negative or active effects on CD8 + T-cells infiltration in BRCA, DLBC, and UVM. Recent research has shown that RUNX1-related pathways may involve crosstalk between fibroblasts and tumor cells, and are closely related to the formation of CAFs [33]. We also observed a significant correlation between RUNX1 expression and CAFs infiltration in almost all tumors. RUNX1 may affect patient prognosis via immune infiltration of CAFs, which is closely related to tumorigenesis. Although causality cannot be established in the current study, these findings indicate that RUNX1 has a strong effect on the regulation of these immune-infiltrating cells and may affect the occurrence and progression of tumors.

Another major finding of our study was that RUNX1 expression correlated with diverse oncogenic signaling pathways in different cancers. RUNX1 is a crucial regulator of TGF-β signaling and plays an important role in several biological processes. Crosstalk between TGF-β signaling and other signaling pathways contributes to aberrant activation of cancer signaling, such as those of the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways [34]. Moreover, the transcription factor RUNX1 enhances the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby promoting tumor progression and metastasis in colorectal cancer [35]. Therefore, it is reasonable to speculate that RUNX1 expression may influence patient prognosis by activating oncogenic signaling pathways in human cancers.

In summary, we systematically analyzed the effect of RUNX1 expression on the prognosis of several human malignancies. Our results suggest that RUNX1 expression is dysregulated in almost all tumors and may have positive or negative effects on the clinical outcomes of patients with cancer. Additionally, an increased level of RUNX1 is associated with the immune infiltrate levels of CAFs and the activation of oncogenic signaling pathways in human cancers, which could be the potential mechanism by which RUNX1 affects patient outcomes. However, further verified experiments have not been performed in human cancers, limiting the analysis of the data. Nevertheless, the findings of our study contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the underlying mechanisms of RUNX1 in human tumors and provide support for subsequent experimental studies.

Conclusions

We found that RUNX1 expression correlates with patient outcomes and immune infiltrate levels of CAFs in multiple tumors. These findings suggest that RUNX1 can function as a potential prognostic biomarker and reflect the levels of immune infiltrates of CAFs in human cancers.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Pan-canceranalysis of RUNX1 mRNA expression level across cancers in the GEPIA database. Fig. S2. Pan-canceranalysis of RUNX1 protein expression level across cancers in the Human Protein Atlas. A. Protein expression of RUNX1 in normal tissuesB. Protein expression of RUNX1 in cancer tissues. Fig. S3. Correlationanalysis between RUNX1 expression and immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells inTIME database. A. Thecorrelation between RUNX1expression and immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells in pan-cancer. B.The immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells and RUNX1 expression was a significant positive correlation inBRCA-Her2, DLBC, and UVM. Table S1. Pan-cancer survivalanalyses of RUNX1 in the 13 types of cancer from PrognoScan database. Table S2. Pan-cancersurvival analyses of RUNX1 in the 33types of cancer from GEPIA database. Table S3. The Coxregression analysis for evaluating the prognostic value of the risk score based on TIMER 2.0 database.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Abbreviations

- BLCA

Bladder urothelial carcinoma

- BRCA

Breast invasive carcinoma

- CAFs

Cancer-associated fibroblasts

- CBF-β

Core binding factor-beta

- CC

Cellular component

- CESC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma

- CHOL

Cholangiocarcinoma

- COAD

Colon adenocarcinoma

- DFS

Disease-free survival

- DLBC

Lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

- ESCA

Esophageal carcinoma

- GBM

Glioblastoma multiforme

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GEPIA

Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis

- GO

Gene Ontology

- GTEx

Genotype-Tissue Expression

- HNSC

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- HPA

Human Protein Atlas

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- KIRC

Kidney renal clear cell carcinoma

- KIRP

Kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma

- LAML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- LIHC

Liver hepatocellular carcinoma

- LGG

Brain lower-grade glioma

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- LUSC

Lung squamous cell carcinoma

- MESO

Mesothelioma

- MF

Molecular function

- OS

Overall survival

- RUNX1

Runt-related transcription factor 1

- RUNXs

Runt-related transcription factors

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- TIMER

Tumor Immune Estimation Resource

- OV

Ovarian cancer

- PAAD

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma

- PCPG

Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma

- PRAD

Prostate adenocarcinoma

- READ

Rectum adenocarcinoma

- SARC

Sarcoma

- SCKM

Skin cutaneous melanoma

- STAD

Stomach adenocarcinoma

- TGCT

Testicular germ cell tumors

- THCA

Thyroid carcinoma

- THYM

Thymoma

- UCEC

Uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma

- UCS

Uterine carcinosarcoma

- UVM

Uveal melanoma

Authors' contributions

Zhouting Tuo, Ying Zhang and Xin Wang carried out the interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. Shuxin Dai, Kun Liu and Dian Xia participated in the collection of data and data analysis. Literature research was conducted by Jinyou Wang. Liangkuan Bi conceived and designed the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No. 2108085MH297), and the Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Science and Technology Rising Stars Training Project (No. 2018KA01).

Availability of data and materials

The data of the current study is available from the following open public databases: TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov), GTEx (https://gtexportal.org/home/datasets), and Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html) as is described above. Other data will be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations (Declaration of Helsinki). Ethical approval of the manuscript was obtained from The Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University Research Ethics Committee (approval no. S20210060). All data are freely available and this study did not involve any human or animal experiments.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhouting Tuo, Ying Zhang and Xin Wang contributed equally to this work and are considered to be co-first authors.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blum A, Wang P, Zenklusen JC. SnapShot: TCGA-Analyzed Tumors . Cell. 2018;173(2):530. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clough E, Barrett T. The Gene Expression Omnibus Database. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1418:93–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3578-9_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito Y, Bae SC, Chuang LS. The RUNX family: developmental regulators in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(2):81–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bushweller JH. CBF–a biophysical perspective. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2000;11(5):377–382. doi: 10.1006/scdb.2000.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lie-A-Ling M, Mevel R, Patel R, Blyth K, Baena E, Kouskoff V, Lacaud G. RUNX1 Dosage in Development and Cancer. Mol Cells. 2020;43(2):126–138. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2019.0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C, Xu D, Xue B, Liu B, Li J, Huang J. Upregulation of RUNX1 Suppresses Proliferation and Migration through Repressing VEGFA Expression in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26(2):1301–1311. doi: 10.1007/s12253-019-00694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitsuda Y, Morita K, Kashiwazaki G, Taniguchi J, Bando T, Obara M, Hirata M, Kataoka TR, Muto M, Kaneda Y, et al. RUNX1 positively regulates the ErbB2/HER2 signaling pathway through modulating SOS1 expression in gastric cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):6423. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24969-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao L, Peng Z, Zhu A, Xue R, Lu R, Mi J, Xi S, Chen W, Jiang S. Inhibition of RUNX1 promotes cisplatin-induced apoptosis in ovarian cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2020;180:114116. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2020.114116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheitz CJ, Lee TS, McDermitt DJ, Tumbar T. Defining a tissue stem cell-driven Runx1/Stat3 signalling axis in epithelial cancer. Embo J. 2012;31(21):4124–4139. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim Y, Lee BB, Kim D, Um S, Cho EY, Han J, Shim YM, Kim DH: Clinicopathological Significance of RUNX1 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. J CLIN MED 2020, 9(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Takayama K, Suzuki T, Tsutsumi S, Fujimura T, Urano T, Takahashi S, Homma Y, Aburatani H, Inoue S. RUNX1, an androgen- and EZH2-regulated gene, has differential roles in AR-dependent and -independent prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(4):2263–2276. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaidzik VI, Teleanu V, Papaemmanuil E, Weber D, Paschka P, Hahn J, Wallrabenstein T, Kolbinger B, Köhne CH, Horst HA, et al. RUNX1 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia are associated with distinct clinico-pathologic and genetic features. Leukemia. 2016;30(11):2160–2168. doi: 10.1038/leu.2016.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Bragt MP, Hu X, Xie Y, Li Z. RUNX1, a transcription factor mutated in breast cancer, controls the fate of ER-positive mammary luminal cells. Elife. 2014;3:e3881. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang L, Gao Y, Song Y, Li Y, Li Y, Zhang H, Li D, Li J, Liu C, Li F. PAK4 phosphorylating RUNX1 promotes ERα-positive breast cancer-induced osteolytic bone destruction. INT J BIOL SCI. 2020;16(12):2235–2247. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.47225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park SJ, Yoon BH, Kim SK, Kim SY. GENT2: an updated gene expression database for normal and tumor tissues. BMC MED GENOMICS. 2019;12(Suppl 5):101. doi: 10.1186/s12920-019-0514-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li T, Fu J, Zeng Z, Cohen D, Li J, Chen Q, Li B, Liu XS: TIMER2.0 for analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. NUCLEIC ACIDS RES 2020;48(W1):W509-W514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Asplund A, Edqvist PH, Schwenk JM, Pontén F. Antibodies for profiling the human proteome-The Human Protein Atlas as a resource for cancer research. Proteomics. 2012;12(13):2067–2077. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201100504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. NUCLEIC ACIDS RES. 2019;47(W1):W556–W560. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chandrashekar DS, Bashel B, Balasubramanya S, Creighton CJ, Ponce-Rodriguez I, Chakravarthi B, Varambally S. UALCAN: A Portal for Facilitating Tumor Subgroup Gene Expression and Survival Analyses. Neoplasia. 2017;19(8):649–658. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2017.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizuno H, Kitada K, Nakai K, Sarai A. PrognoScan: a new database for meta-analysis of the prognostic value of genes. BMC MED GENOMICS. 2009;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, Sun Y, Jacobsen A, Sinha R, Larsson E, et al. Integrative analysis of complex cancer genomics and clinical profiles using the cBioPortal. SCI SIGNAL. 2013;6(269):l1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Nastou KC, Lyon D, Kirsch R, Pyysalo S, Doncheva NT, Legeay M, Fang T, Bork P, et al. The STRING database in 2021: customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. NUCLEIC ACIDS RES. 2021;49(D1):D605–D612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhou Y, Zhou B, Pache L, Chang M, Khodabakhshi AH, Tanaseichuk O, Benner C, Chanda SK. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. NAT COMMUN. 2019;10(1):1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanehisa M, Furumichi M, Sato Y, Ishiguro-Watanabe M, Tanabe M. KEGG: integrating viruses and cellular organisms. NUCLEIC ACIDS RES. 2021;49(D1):D545–D551. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feng X, Zheng Z, Wang Y, Song G, Wang L, Zhang Z, Zhao J, Wang Q, Lun L. Elevated RUNX1 is a prognostic biomarker for human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2021;246(5):538–546. doi: 10.1177/1535370220969663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sangpairoj K, Vivithanaporn P, Apisawetakan S, Chongthammakun S, Sobhon P, Chaithirayanon K. RUNX1 Regulates Migration, Invasion, and Angiogenesis via p38 MAPK Pathway in Human Glioblastoma. CELL MOL NEUROBIOL. 2017;37(7):1243–1255. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0456-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rooney N, Mason SM, McDonald L, Däbritz J, Campbell KJ, Hedley A, Howard S, Athineos D, Nixon C, Clark W, et al. RUNX1 Is a Driver of Renal Cell Carcinoma Correlating with Clinical Outcome. CANCER RES. 2020;80(11):2325–2339. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong M, He J, Li D, Chu Y, Pu J, Tong Q, Joshi HC, Tang S, Li S. Runt-related transcription factor 1 promotes apoptosis and inhibits neuroblastoma progression in vitro and in vivo. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01558-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dulak AM, Schumacher SE, van Lieshout J, Imamura Y, Fox C, Shim B, Ramos AH, Saksena G, Baca SC, Baselga J, et al. Gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas of the esophagus, stomach, and colon exhibit distinct patterns of genome instability and oncogenesis. CANCER RES. 2012;72(17):4383–4393. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meng G, Wei J, Wang Y, Qu D, Zhang J. miR-21 regulates immunosuppression mediated by myeloid-derived suppressor cells by impairing RUNX1-YAP interaction in lung cancer. CANCER CELL INT. 2020;20:495. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01555-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhu SY, Wu QY, Zhang CX, Wang Q, Ling J, Huang XT, Sun X, Yuan M, Wu D, Yin HF. miR-20a inhibits the killing effect of natural killer cells to cervical cancer cells by downregulating RUNX1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;505(1):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kapusta P, Dulińska-Litewka J, Totoń-Żurańska J, Borys A, Konieczny PS, Wołkow PP, Seweryn MT: Dysregulation of Transcription Factor Activity During Formation of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. INT J MOL SCI 2020, 21(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Gonzalez DM, Medici D. Signaling mechanisms of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. SCI SIGNAL. 2014;7(344):e8. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Q, Lai Q, He C, Fang Y, Yan Q, Zhang Y, Wang X, Gu C, Wang Y, Ye L, et al. RUNX1 promotes tumour metastasis by activating the Wnt/β-catenin signalling pathway and EMT in colorectal cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):334. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1330-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Pan-canceranalysis of RUNX1 mRNA expression level across cancers in the GEPIA database. Fig. S2. Pan-canceranalysis of RUNX1 protein expression level across cancers in the Human Protein Atlas. A. Protein expression of RUNX1 in normal tissuesB. Protein expression of RUNX1 in cancer tissues. Fig. S3. Correlationanalysis between RUNX1 expression and immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells inTIME database. A. Thecorrelation between RUNX1expression and immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells in pan-cancer. B.The immune infiltration of CD8+ T-cells and RUNX1 expression was a significant positive correlation inBRCA-Her2, DLBC, and UVM. Table S1. Pan-cancer survivalanalyses of RUNX1 in the 13 types of cancer from PrognoScan database. Table S2. Pan-cancersurvival analyses of RUNX1 in the 33types of cancer from GEPIA database. Table S3. The Coxregression analysis for evaluating the prognostic value of the risk score based on TIMER 2.0 database.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the current study is available from the following open public databases: TCGA (https://cancergenome.nih.gov), GTEx (https://gtexportal.org/home/datasets), and Metascape (https://metascape.org/gp/index.html) as is described above. Other data will be obtained from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.