Abstract

The pandemic has disproportionately affected African American college students, who have experienced significant work‐related, academic, financial, and socio‐emotional challenges due to COVID‐19. The purpose of the study is to investigate how African American students cope with the severe impact of COVID‐19 on their emotional well‐being leveraging the benefits of self‐care coping measures, COVID‐19 knowledge, and communication with others to enhance perceived control and social connectedness. A structural equation modeling and a path analysis of 254 responses from a Historically Black College and University showed that emotional well‐being was positively predicted by self‐care coping strategies, feelings of being in control in life, and social connectedness. In addition, respondents who adopted mind−body balance coping strategies, those who are knowledgeable about COVID‐19, and those in more constant communication with others attained a strong sense of being in control, and in turn the empowerment increased their emotional well‐being.

Keywords: African American college students, communication, coping strategies, COVID‐19, emotional well‐being, feelings of control, pandemic

1. INTRODUCTION

African Americans are disproportionately impacted by COVID‐19 pandemic as evidenced by 1.1 times higher infection, 2.9 times higher hospitalization, and 1.9 times higher death rates than White Americans (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on African Americans also existed in the fact that many of them suffer from mental and social health problems due to isolation as a result of social distancing and stay‐at‐home mandates, as well as lower social economic status and social stigma that prevent them from getting mental health treatments (Alvidrez et al., 2008; Campbell & Mowbray, 2016; Copeland & Snyder, 2011; Novacek et al., 2020; Perrin et al., 2009). When faced with the enormous uncertainty and health threats of COVID‐19, fear is a known response, and yet health communication literature suggests that seeking information for further knowledge may help reduce the uncertainty and threats one experiences and ultimately regain feeling in control (Case, 2002). Substantial coping strategies may include taking self‐care measures to stay physically and psychologically healthy, including exercising to maintain physical health, staying busy and keeping oneself entertained, as well as staying in communication with family, friends, co‐workers and others in the world, especially using technology and social media to enhance the sense of connectedness of others. On top of dealing with COVID‐19's devastating effects, college students including Historically Black College and University (HBCU) students also struggled to adapt to new full‐online instruction mode which may add to another level of frustration, challenge, and uncertainty. Thus, whether HBCU students are doing well in online classes may play a key factor in feeling in control.

COVID‐19 has severely impacted the lives of all Americans. In March 2020; the World Health Organization declared coronavirus a global pandemic and social distancing measure was announced globally. In April 2000, most US states ordered state‐wide lockdown. In October 2020, a report issued by the American Psychology Association declared a national mental health crisis. College students, the generation Z adults (ages 18−23), have been found to be the most affected by COVID‐19 as young or emerging adults in the United States and worldwide (APA, 2020; Conrad et al., 2021; Prowse et al., 2021). Faced with unprecedented uncertainty due to sudden school closure and mandatory relocation, social distancing measures limiting in‐person social interactions, and forced transition to virtual learning, college students experienced negative mental health issues including stress, loneliness, anxiety, depression, and other symptoms (Cao et al., 2020; Conrad et al., 2021; Y. Li et al., 2021; Luchetti et al., 2020; Prowse et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2020). However, less is known about how they are coping with the psychological consequences of COVID‐19. Even less is known about how well HBCU students as a particularly vulnerable population were coping with the impact of COVID‐19 on their emotional well‐being.

Therefore, the purpose of the study is to examine how HBCU students leveraged the benefits of self‐care coping measures, COVID‐19 knowledge, and communication with others to enhance perceived control and social connectedness, and in turn, preserve their emotional well‐being in the face of COVID‐19's devastating impact.

1.1. Coping strategies, self‐care and emotional well‐being

When dealing with stressful life situations, people may seek coping measures or strategies to protect themselves from psychological harm, a behavior that importantly mediates the impact of stressful events. The coping response is one of the dimensions of coping that represents the things that people do, their concrete efforts to deal with the life‐strains (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978), and a person's efforts to manage demands that exceed their personal resources (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These types of coping activities, some called behavioral activation, are found to have diverted and sparked positive emotions critical to resilient outcomes and recovery after disastrous events (Polizzi et al., 2020). During the COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown, increased stress and uncertainty make it more important, and challenging than ever for college‐aged young adults whose mental health has been disproportionately affected to identify constructive coping strategies to look after themselves mentally and physically. In Lazarus and Folkman's (1984) transactional theory of stress, coping is considered as constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage internal or external stressors. It is argued that both behavioral and cognitive strategies must be implemented to achieve the adaptation that facilitates balanced emotions and perception of well‐being (Mayordomo‐Rodríguez et al., 2015).

Numerous studies have indicated that individual differences in how they cope with the stressors may determine mental and physical health outcomes (Lazarus, 1993; Matheson & Anisman, 2003). Problem‐focused coping enables individuals to address the stressor itself by taking steps to manage its impact, while emotion‐focused coping tries to minimize the distress caused by the stressor. Thus, when an individual engages in problem‐focused coping, the goal is problem‐solving, whereas emotion‐focused coping strategies used methods to regulate one's emotional responses, which often involve attempts to avoid or escape from them. Researchers argued that active forms of coping (e.g., problem‐solving) tend to facilitate positive outcomes including better adaptation, mental health, and well‐being, whereas passive forms of coping, such as denial, blame, and avoidance behaviors, are often linked to negative outcomes such as symptoms of depression (Carver et al., 1989; Lazarus, 1993; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Several recent studies have indicated that young adults' well‐being is negatively associated with passive or emotion‐based coping, while positively correlated with problem‐focused coping and seeking social support (Mayordomo‐Rodríguez et al., 2015; Sagone & De Caroli, 2014; Tremolada et al., 2016). For instance, Mayordomo‐Rodríguez et al. (2015) found that young adults' use of problem‐focused coping including positive appraisal and seeking social support predicted a significant portion of well‐being, while emotion‐focused coping including negative self‐focus and overt emotional expression negatively predicted well‐being.

Coping strategies young adults adopted in dealing with difficult situations and negative emotions ranged from commonly utilized proactive coping strategies including seeking and reaching out to others to make themselves feel better, keeping themselves busy, and engaging in enjoyable activities, to the least reported strategies employing a passive and avoidance‐oriented approach (Diefendorff et al., 2008). Similarly, another study that looked at the role coping strategies and perceived support played in predicting adolescents' and young adults' emotional well‐being reported that the preferred adaptive strategies are: cognitive coping (active coping and planning), followed by seeking instrumental and emotional support. Maladaptive coping such as venting and self‐blame were more common among girls and young women than among boys and young men (Tremolada et al., 2016).

Self‐care coping is a form of active coping, an effort to take an active role in maintaining one's health and well‐being. When considered from a dynamic perspective, health can be defined as the ability to adapt and self‐care (Huber et al., 2011). Healthy ways of self‐care have proven beneficial in maintaining one's health, self‐esteem, and well‐being (Bermejo‐Martins et al., 2021; Coster & Schwebel, 1997; Matarese et al., 2018). Behavioral and cognitive coping efforts related to self‐care can cover a wide range of physical, social, emotional, and spiritual activities including exercise, sleep, eating nutritious food, connecting with friends/family, doing something enjoyable, keeping busy, staying informed, sharing feelings with others, devotion to religion, meditations, and taking prescribed medications (Bermejo‐Martins et al., 2021; Kar et al., 2021; Kidd et al., 2008; Prowse et al., 2021).

Furthermore, how younger adults and college students cope with COVID‐related stress is crucial to their emotional well‐being because of the inverse relationship between stress levels and psychological symptoms. Prowse et al. (2021) examined the relationship between coping strategies and emotional well‐being and found that Canadian college students' frequent use of unhealthy self‐care coping strategies including cannabis and alcohol use, sleeping, and more screen time were positively associated with higher levels of stress and negative mental health outcomes. In another study, Y. Li et al. (2021) surveyed a large cohort of college students in China at the onset of the outbreak and during the “under‐control” remission period of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Findings revealed that lack of physical exercise and social support, as well as having a dysfunctional family were associated with negative psychological outcomes among the Chinese population, who saw a 73% jump in mental health problems after the pandemic. Other coping responses to pandemic stress, including keeping busy, hoping for the best and believing in God, were also adopted among young adults (20–30‐year olds) and university‐educated respondents who experienced worse mental health problems, while avoiding thinking about the pandemic, being unaware of coping strategies, or struggling to cope was associated with higher rates of stress and depression (Kar et al., 2021). On the other hand, Stieger et al. (2021) reported that Austrian adults' emotional well‐being was related to simply being outdoors. These and similar studies highlight the important role coping strategies potentially play in relieving or worsening the strain of COVID‐19 on an individual's mental health and may be especially a prominent factor for African American young adults given COVID‐19's disproportionate impact.

1.2. Perceived control, coping strategies, and emotional well‐being

Perceived control has been defined as “the extent to which one regards one's life chances as being under one's own control” (Pearlin & Schooler, 1978, p. 5). This personal sense of control was also referred to as “the belief that one can determine one's own internal states and behavior, influence one's environment, and/or bring about desired outcomes” (Wallston et al., 1987, p. 5). Thus, generally regarded as an important personal resource (Turner & Noh, 1988), the control beliefs of individuals are an integral part of the stress‐coping process (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), and having a sense of control helps people believe they have the capacity to achieve desirable outcomes and avoid undesirable ones (Skinner, 1996). Prior research findings supported that perceived control tends to enhance an individual's capacity and confidence to cope, promote successful coping, and in turn, improve the subjective experience of the environment and health outcomes (Lachman, 2006; Wallston et al., 1987; Zheng et al., 2020).

While control is reflected in people's belief that personal resources can be accessed to achieve desirable outcomes (Polizzi et al., 2020), how much control they perceive over the problem event may well be dependent on the coping strategies they undertake. Research in general has shown that individual differences in perceived control linked to varying coping strategies were associated with successful coping during stressful situations. For instance, Black youths' use of approach/active coping strategies such as social support and problem‐solving, as compared with avoidance coping strategies was related to a higher sense of personal control over subjective feelings of distress evoked by discrimination experience, while avoidance coping led to feelings of distress (Scott & House, 2005). In contrast, Folkman (1984) proposed that problem‐focused coping strategies can be adaptive if the stressor is controllable, while emotion‐focused coping strategies can be helpful when the stressor is less controllable. As the Black youth participants struggled to cope with emerging mental health difficulties (e.g., anxiety), most of their coping strategies were identified as emotion‐focused such as avoidance, which the authors argued to be more helpful as aspects of COVID‐19 are out of the participants' control (J. S. Parker et al., 2021), consistent with Folkman's (1984) assumption.

1.2.1. Perceived control and emotional well‐being

In a similar way that studies have linked coping strategies and perceived control, several studies have shown that perceived control is associated with young adults' emotional well‐being. Perceived control, subjectively felt the ability to control one's environment or life situations, has been associated with positive well‐being and better health, particularly during and following uncontrollable stressors such as sexual assaults, heart attack or even aging (e.g., Ferguson & Goodwin, 2010; Frazier, 2003; Moser & Dracup, 1995). Prior studies that examined coping beliefs and psychological well‐being among adolescents and young adults have reported positive effects of control beliefs on emotional health and academic performance. For instance, Hortop et al. (2013) found that a global sense of control accelerated the goal progress and enhanced perceived emotional well‐being in young adults who are highly motivated. Similarly, perceived academic control is a subset of the control construct pertaining to students' judgment on their perceived ability to control the academic outcome (e.g., P. C. Parker et al., 2016). Recent studies have found that a strong sense of control working hand in hand with optimism could buffer the stress associated with the freshman year experience (Yeo & Yap, 2020), while college freshmen who have low perceived control reported lower grades than those with high perceived control (Stupnisky et al., 2012). Beyond grades, first‐year college students with perceived control were also less likely to experience negative emotions (Stupnisky et al., 2013).

Within the pandemic context, addressing perceived control is particularly relevant because of the inverse relationship between psychological symptoms and perceived control. Empirical evidence from several studies suggested that when respondents perceived a higher level of COVID‐19 uncertainty, they tended to experience insomnia (Zheng et al., 2020) or intensified negative emotions (e.g., anxiety and depression), which then can be exacerbated by a lower level of perceived efficacy (Dai et al., 2021). In other words, when people lack confidence in coping with the pandemic or felt at loss of control in the COVID‐19 situation, their emotional state worsened. On the other hand, perceived control of COVID‐19 was reported to moderate the perceived severity of the COVID‐19 pandemic on mental health (J.‐B. Li, Yang, Dou, Cheung, 2020; J.‐B. Li, Yang, Dou, Wang, et al., 2020), improve emotional well‐being (Yang & Ma, 2020), and can buffer the psychological effects of pandemic severity on participants' perceived health status and life satisfaction (Zheng et al., 2020).

1.2.2. Perceived control, coping strategies, and emotional well‐being

With studies that support the links between coping strategies and perceived control, and between perceived control and emotional health, it could be argued that individuals who practice active coping tend to experience an increased sense of control, and in turn, achieve high emotional well‐being, though few studies have explored the mediation effect that perceived control has on coping strategies and emotional well‐being. One exception is the study that tested the mediating effect of perceived control on coping strategies and emotional health. Dijkstra and Homan (2016) varied coping strategies on the dimension of engagement, and findings suggested that more engaged coping such as active confrontation and reassuring thoughts predicted more sense of control and through such control improved emotional well‐being, whereas disengaged coping such as passive reaction pattern and avoidance negatively predicted perceived control and ultimately worsened emotional well‐being. In a similar study of 2413 Flemish employees, perceived control was a more important mediator than psychological contract for the relationship between job security and behavioral coping responses (Vander Elst et al., 2016). The basis for the mediation effect is that perceived control explains why active coping has more positive effects on psychological well‐being, in that people who actively deal with the situation are more likely to experience a sense of control, and are able to do something about it, and vice versa (Dijkstra et al., 2009). Studies are necessary to replicate these results for African American young adults.

1.3. Knowledge and perceived control

Knowledge is considered a type of health literacy (Webster & Heeley, 2010). In health communication literature, knowledge about a disease or health behavior plays a crucial role in effectively reducing an individual's perceived feelings of uncertainty, leading to a strong sense of control. As people are faced with uncertainty about a health threat, they are often motivated to seek out information to fill the knowledge gap and in turn, increase their feelings of being in control (Case, 2002; Street, 2003). Several studies provided evidence for similar links between individuals' knowledge or information seeking and perceived reduced health risk (Bish & Michie, 2010; Eastwood et al., 2009), improved healthy behaviors (Petrovici & Ritson, 2006; Zhang et al., 2012), and enhanced self‐efficacy (Fung et al., 2018), which mediated the knowledge effect on their feelings of being in control.

1.3.1. Knowledge, perceived control, and emotional well‐being

Recently, there is support that knowledge could facilitate positive mental health outcomes through perceived control. Yang and Ma (2020) found that knowledge of COVID‐19 contributes to an elevated sense of control in the pandemic, in turn, reducing the negative emotions and maintaining positive feelings (i.e., happiness). While knowledge may serve as a protective factor of emotional well‐being, several studies have found that African American adults are among the least knowledgeable. For instance, measured in the early stages of the pandemic, knowledge of COVID‐19 was reported lower in the African American communities and young adults aged 18−24 (McCormack et al., 2021); African American adults answered the least accurate COVID‐19 information in comparison with all other ethnic groups (Jones et al., 2020); had the least number of people who had high knowledge score (Alobuia et al., 2020); were less knowledgeable regarding its spread, symptoms, and required social distancing behaviors (Alsan et al., 2020). Even the Kaiser Family Foundation's (KFF) March Coronavirus Poll of adults 18 and above indicated that nonwhite ethnic groups, including African Americans had lower knowledge of COVID‐19 than the White groups (KFF, 2020). Therefore, with the lack of COVID‐19 knowledge among average African American adults 18 and above and the mental health strain on this population in mind, this study hypothesizes that HBCU students with more knowledge about COVID‐19 will perceive a higher level of control and in turn help them better cope with the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic.

1.4. Communication, coping strategies, social connectedness, and emotional well‐being

Social distancing restriction has raised concern about the possibility of increasing feelings of loneliness, especially in vulnerable groups. As humans are social beings, feeling alone and lacking social connections with others can be detrimental to our physical and mental health (Bzdok & Dunbar, 2020; Holt‐Lunstad, 2018; Leigh‐Hunt et al., 2017), especially as we rely on each other for health and well‐being (Snyder‐Mackler et al., 2020). In times of uncertainty and distress, social connection provides us with needed support when dealing with negative emotions (S. E. Cohen & Syme, 1985), and can act as a potential buffer against negative physical and mental health outcomes, and promote resilience when faced with the unprecedented global stressor by easing people's anxieties towards the pandemic (Nitschke et al., 2021).

While social distancing restrictions required people to withdraw from their normal lives and practice social distancing, the potential for the negative consequences of physical and mental health increased. Several studies have explored whether social distancing and stay‐at‐home orders contributed to a large increase in feelings of social isolation due to the lack of communication and social interaction. Luchetti et al. (2020) measured American adults' perceived loneliness at the early stage of the pandemic when social distancing and stay‐at‐home orders were issued. The results show that there was no significant increase in loneliness, and there was even an increase in perceived social support. Nevertheless, young adults were more vulnerable to experiencing loneliness than older adults, and two later studies yield similar findings (Kar et al., 2021; Rumas et al., 2021). Another national survey of loneliness and mental health administered to a sample of 1013 English‐speaking US adults during the third week of “shelter‐in‐place” period (i.e., April 9−10) confirmed that the loneliness level was elevated, with 62% of adults among those who were staying at home reporting feeling socially isolated much of the time. The lonely people were also more likely to experience moderate and severe depression than the non‐lonely individuals (55% vs. 15%). As more states implemented stay‐at‐home orders in the later stages of the National Emergency “sheltering‐in‐place” order, US adults on average became lonelier and more depressed (Killgore et al., 2020).

As the emotional well‐being declined, the pandemic also disrupted college students' typical social experiences and well‐being, but technology provided an opportunity for communication and social interactions to compensate for the lack of in‐person social connection (Jeste, 2020), and improved adaptation and mental health. College students may be particularly skillful in using technology as a communication tool due to the widespread use among this age group. The existing communication literature has presented conflicting evidence in the role technology played in promoting or hindering social interaction and the resulting well‐being among younger generation (Subramanian, 2017). Most studies have typically examined the association between screen time or network size and mental health during the pandemic among teens, young adults, and average adults, and the findings have been mixed. In a study that looked at social media use and young (aged 16_21) web users' psychological well‐being during the pandemic, passive social media use rather than communication, and uncontrolled social media time were seen as an emotion‐focused coping strategy to escape from negative thoughts, which in turn led to heightened feelings of anxiety, apathy, depression, and disconnectedness from social reality (Hudimova et al., 2021). Meanwhile, Austrian adults were asked to track their own well‐being (i.e., happiness), experiences of loneliness and daily screen time during a 21‐day period in lockdown and the findings indicated that greater sense of loneliness and daily screen time were negatively associated with emotional well‐being (Stieger et al., 2021), with screen time also contributing to higher sense of loneliness. Although it is unclear what the respondents spent their screen time on, the results suggested more screen time does not buffer against negative psychological outcomes. Similarly, Rumas et al. (2021) examined factors affecting loneliness and quality of life during the baseline period (April 21−25) and longitudinally (May 22−27), and findings suggested that at the baseline level, having more interactions with friends and family was related to lower loneliness, whereas over one month time with having more virtual social contacts with people outside their household, respondents reported more loneliness as compared with having in‐person contacts with others. In contrast, the findings from a survey of 981 Austrians indicated that greater social network sizes used as a measure of social connectedness was associated with reduced levels of stress, as well as general and COVID‐19 pandemic‐specific worries (Nitschke et al., 2021). People with a larger social network of unique individuals with whom they communicated during the lockdown appeared to be more resilient in times of adversity, reporting less stress and worry. Further, David and Roberts (2021) suggested that technology use has the potential to mitigate the negative impact of social distancing on social connections and in turn, well‐being. They found that increased smartphone use during the pandemic among college students was linked to fostered social connection and well‐being. Whereas social distancing restriction is negatively associated with perceived social connection, technology use can be used to moderate such relationships. Instead of feeling pulled apart, the more frequently people use smartphones to stay socially connected, the more they feel “pulled together.” The authors argued that although technology is not a substitute for face‐to‐face interaction, utilizing technology to stay socially connected should be encouraged.

Prior media research argued that the benefits or drawbacks of social technology on social relationships are dependent on the media features that afford users to engage in active or passive media use, which is of particular relevance to perceived social connectedness (Nesi et al., 2018). For instance, passive viewing of Instagram posts or TikTok video does not provide real‐time interaction and interpersonal cues, whereas meeting up on Zoom, face‐to‐face conversation on Facetime, social media, or even texting and chatting on the phone are a closer resemblance of interpersonal communication with close and distant others, and in turn provides a strong sense of social connectedness (Hamilton et al., 2020).

Active coping in the form of self‐care including staying busy, keeping oneself entertained and healthy is similarly linked to social connectedness, whereas uniquely through a combined social and parasocial interactions. During the social restriction, these self‐care activities may include (1) exercising with a small group of friends or exercising with online videos with instructors or peers, (2) entertaining oneself by likely watching media streaming, live concerts on social media, and playing video games, (3) as well as engaging oneself in work, school and family functions to stay busy (see Table 2). Some of them involved social interaction in a physical environment and some related to online parasocial interaction with media persona such as online characters, actors, and performers in the media. Parasocial relationships are defined as “feelings of intimacy and kinship that individuals develop with celebrities and fictional characters transcending episodic media experiences” (Bond, 2021, p. 4). Although parasocial relationships that media users develop towards media personae are not reciprocated like real social relationship, such mediated interpersonal relationships augmented by the explosion of digital media could supplement real social relationships especially in light of social restriction (Jarzyna, 2021). The uses and gratifications theory (Rubin et al., 1985) proposed that people are motivated to seek out media experiences that gratify personal needs and interests. To that extent, based on social and psychological circumstance, parasocial interactions can meet individuals' desire for social contact (Hartmann, 2016), which in turn improve the sense of social connectedness.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of activities and media use behavior

| % | N | |

|---|---|---|

| How do you spend your time during quarantine? | ||

| Doing my school work | 81.5 | 207 |

| Spending time with my family | 66.9 | 170 |

| Communicating with my friends online | 63.8 | 162 |

| Personal entertainment online (streaming videos; live concerts and games) | 63.0 | 160 |

| Internet surfing | 57.1 | 145 |

| Working on my job | 44.5 | 113 |

| Outdoor physical activities (taking a walk or hike) | 44.1 | 112 |

| Reading books or articles | 39.8 | 101 |

| Indoor physical activities (exercise with online videos) | 37.8 | 96 |

| Choice hanging out with my friends | 33.9 | 86 |

| Other | 7.1 | 18 |

| How do stay connected with their loved ones (i.e., family, friends, and romantic partners)? | ||

| Texting | 90.6 | 230 |

| Phone calls | 85.8 | 218 |

| Facetime | 83.9 | 213 |

| Social media | 78.0 | 198 |

| Face‐to‐face | 65.0 | 165 |

| Mobile apps | 33.5 | 85 |

| Zoom | 22.0 | 56 |

| 9.4 | 24 | |

| Skype | 3.1 | 8 |

| Other | 1.2 | 3 |

| How do you stay connected with people at work? | ||

| Texting | 39.8 | 101 |

| Phone calls | 30.3 | 77 |

| Face‐to‐face | 28.7 | 73 |

| Other/NA | 28.0 | 71 |

| 22.4 | 57 | |

| Social media | 21.3 | 54 |

| Zoom | 20.1 | 51 |

| Facetime | 14.2 | 36 |

| Mobile apps | 8.3 | 21 |

| Skype | 5.1 | 13 |

| How do you stay connected with other people in the world? | ||

| Social media | 88.6 | 225 |

| Texting | 54.3 | 138 |

| Phone calls | 43.7 | 111 |

| Facetime | 41.7 | 106 |

| Mobile apps | 28.7 | 73 |

| Zoom | 20.1 | 51 |

| 18.9 | 48 | |

| Face‐to‐face | 15.0 | 38 |

| Skype | 2.0 | 5 |

| Other | 2.0 | 5 |

| Which social media are you using to stay connected? | ||

| 92.5 | 234 | |

| 75.1 | 190 | |

| 51.8 | 131 | |

| Snapchat | 51.8 | 131 |

| Tik Tok | 27.3 | 69 |

| Other | 2.8 | 7 |

Social connectedness provides an opportunity for people living in the throes of the pandemic to seek, receive, and provide social support. Although researchers have generally agreed that the negative impact of stress decreased for people with strong social support (S. Cohen & Wills, 1985), and recent studies also confirmed that social connectedness/connection reduced people's stress level and enhanced their psychological well‐being during the pandemic lockdown (David & Roberts, 2021; Nitschke et al., 2021), this stress‐buffering effect of social support appeared to operate by bolstering perceived control (Krause, 1987). As social connectedness provides increased social support from friends, family and community, perceived control also increases to “buffer” (protect) individuals from potentially harmful influence of excessive stress (Cummins, 1988) and build empowerment in older adults (Johnston et al., 2011). As Meehan et al. (1993) took a further look at the relationship between social support, perceived control, and psychological well‐being, they found a significant relationship between social support and positive dimensions of subjective well‐being (e.g., happiness and gratification) and perceived control, yet perceived control was associated with both positive and negative dimensions of subjective well‐being (e.g., uncertainty and strain). Thus, it is possible that social connectedness would have an indirect mediating effect on psychological well‐being by working through perceived control during an uncertain and distressful life experience, such as the pandemic. Taken together, the current study posits that college students' active use of technology to communicate with close and distant social ties along with in‐person interaction, when possible, will likely lead them to experience social and emotional connectedness, which bolster perceived control and ultimately help protect their emotional wellbeing. Further, besides the proposed direct link between HBCU students' coping strategies and emotional well‐being, we also propose that active coping will take on a similar pathway to emotional well‐being via social connectedness and through perceived control.

In summary, the purpose of the study is to examine how proactive coping strategies in the form of healthy self‐care coping measures, including staying busy, keeping oneself entertained, exercising, staying in constant communication with others, and keeping self‐informed during the COVID‐19 pandemic, impact HBCU students' emotional health. Of particular interest is the mediating roles of perceived control and social connectedness between proactive coping strategies, COVID‐19 knowledge, communication, and emotional well‐being.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants and procedure

An online survey was conducted between May and June 2020 to examine factors affecting HBCU student's perceived emotional well‐being during this stressful and uncertain time. A total of 254 respondents at an HBCU university in the Southeastern region of the United States completed the survey on Qualtrics. About 75.6% were female (N = 192) and 24.4% were male (N = 62). The majority of the respondents are African American (93.7%), with an average age of 21.36 (SD = 2.67), ranging from 18 to 35 years old. Most of them are seniors (40.6%) and juniors (37%), followed by sophomore (16.5%), graduate students (4.3%), and freshmen in college (1.6%). Respondents were given extra credit incentives and were assured of voluntary participation and confidentiality. After viewing a consent form approved by the university's Institutional Review Board, respondents were invited to answer a set of questions related to coping strategies, COVID‐19 knowledge, communication experience with others, and their emotional well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the university's Institutional Review Board.

2.2. Measures

To examine the research questions and proposed model, we measured variables including coping strategies, perceived knowledge of the COVID‐19, time spent communicating with others, feeling of having control in life, perceived connectedness, and emotional well‐being. Means and standard deviations for all measures are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Coping strategies | 3.98 | 0.76 | ||||||

| 2 | Knowledgeable | 3.74 | 0.83 | 0.25** | |||||

| 3 | Time spent on communicating | 3.70 | 2.01 | 0.12 | 0.09 | ||||

| 4 | Feelings of control in life | 3.41 | 1.02 | 0.43** | 0.24** | 0.10 | |||

| 5 | Feeling connected | 3.95 | 0.97 | 0.27** | 0.06 | 0.20** | 0.31** | ||

| 6 | Emotional well‐being | 3.55 | 1.03 | 0.45** | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.60** | 0.29** |

p < 0.01.

2.2.1. Coping strategies

Respondents' coping strategies (participant α = 0.55) were measured by three items (1) “I exercise to stay healthy”; (2) “I keep myself busy”; (3) “I keep myself entertained” (Diefendorff et al., 2008; Kar et al., 2021; Prowse et al., 2021) on a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

2.2.2. Perceived knowledge of COVID‐19

COVID‐19 knowledge was measured using “How knowledgeable would you say you are about the COVID‐19 pandemic?” on a 5‐point Likert scale from 1 = not all knowledgeable to 5 = very knowledgeable.

2.2.3. Time spent on communicating with others

This variable was assessed by asking respondents how many hours they spent daily communicating with their family members, friends, significant others, co‐workers, and others in general, respectively. Five items were included, for example, “How much time do you spend communicating with your family on a daily basis?” and “How much time do you spend communicating with your friends on a daily basis?”

2.2.4. Feeling of having control in life

Perceived ability to control one's life situations was assessed using two items (participant α = 0.60) including “I feel things in my life are generally under control” and “I am handling my online class well,” on a 5‐point scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

2.2.5. Feeling connected with others

To examine the perceived connectedness among HBCU students, one‐single item was used; namely, “In general, I feel socially connected,” on a 5‐point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree.

2.2.6. Emotional well‐being

This variable was evaluated by asking the respondents to indicate their state of emotional well‐being using “How is your emotional well‐being” from 1 = extremely bad to 5 = extremely good.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive statistics of variables and correlation

As shown in Table 1, the mean scores, standard deviations, and Pearson's correlations of all variables were presented using SPSS 27. Coping strategies were found to be positively correlated with perceived knowledge of the COVID‐19 pandemic, feeling of being in control in life, feeling connected, and emotional well‐being. Perceived knowledge of the COVID‐19 pandemic and feeling of control in life were shown to be in positive correlation. Time spent on communication with others was positively associated with feeling connected. Feelings of being control in life during the pandemic were also positively related to feeling connected and emotional well‐being Feeling connected with others was found to be associated with emotional well‐being.

3.2. Test of hypothesized model and path analysis

After examining the correlation among key variables, structural equation modeling (SEM) and a path analysis were conducted using AMOS version 21. With emotional well‐being as the primary outcome, the analysis focused on the direct and indirect effects of COVID‐19 coping strategies, knowledge of the COVID‐19 pandemic and time spent on communicating with others on emotional well‐being with feelings of being in control, and connectedness with others as mediating variables. Sense of control and connectedness are examined separately as mediators.

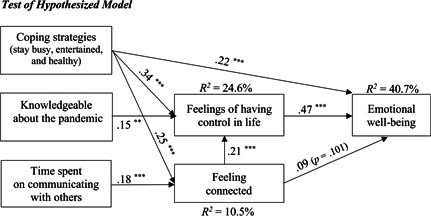

The proposed model (N = 254) demonstrated a good model fit to the data, χ 2 (4) = 7.614 (p = 0.107), CMIN/DF = 1.903, GFI = 0.990; CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.060, TLI = 0.945, NFI = 0.971 (see Figure 1). The value of R 2 was 0.25 for feelings of having control in life, 0.21 for feeling connected, and 0.41 for emotional well‐being. Coping strategies and knowledge of the pandemic account for 25% variance in feelings of having control in life while coping strategies and time spent on communication with others can explain 21% of the variation for feeling connected. As to emotional well‐being, coping strategies and feelings of having control in life can account for 41% of the variation.

Figure 1.

Test of hypothesized model. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

The results of path analysis showed that seven paths were found to have a high degree of significance except for the path from connectedness with others to emotional well‐being (β = 0.09, p = 0.101, CI: 90% [−0.019, 0.196]). Coping strategies, including staying busy, entertained, and being healthy, significantly predicted feelings of having control in life (β = 0.34, p < 0.001, CI: 90% [0.232, 0.452]), feeling connected (β = 0.25, p < 0.001, CI: 90% [0.121, 0.381]), as well as directly influencing emotional well‐being (β = 0.22, p < 0.001, CI: 90% [0.112, 0.331]), indicating that coping strategies resulted in a higher degree of control, connectedness, and emotional well‐being.

Being knowledgeable about the pandemic showed a significant and positive relationship with feelings of having control in life (β = 0.15, p = 0.009, CI: 90% [0.040, 0.257]), indicating respondents equipped with more knowledge about the pandemic were more likely to feel more control in their life. Time spent on communication with others significantly predicted feelings of social connectedness (β = 0.18, p = 0.003, CI: 90% [0.059, 0.292]); when respondents spent more time on communication it resulted in a higher degree of feeling connected. Meanwhile, feeling socially connected was significantly and positively linked to feelings of having control in life (β = 0.21, p < 0.001, CI: 90% [0.085, 0.318]), revealing individuals with higher perceived social connectedness were more likely to have feelings of being in control. Last, feelings of control in life directly and significantly predicted emotional well‐being (β = 0.47, p < 0.001, CI: 90% [0.369, 0.578]), indicating a higher degree of feelings of having control increased their emotional well‐being.

To sum up, the results revealed that feelings of control and connectedness contribute to emotional well‐being differently. Respondents who adopted healthy coping strategies (staying busy, keeping oneself entertained, and exercising to maintain physical health), who are knowledgeable about COVID‐19, and in more constant communication with others attain a strong sense of being in control, and in turn the empowerment increases their emotional well‐being. Although connectedness with others is also strongly linked to coping strategies and communication, it is not directly linked to emotional well‐being. Instead, its effect on emotional health is also mediated by feelings of being in control.

3.3. Activities and media use behavior during the pandemic

To further explore what activities HBCU students engaged themselves with during the lockdown, and the type of media chosen for communication with different groups of people including family, friends, romantic partners, co‐workers, and other people in their lives, we analyzed the descriptive data from multiple responses for each targeted question (see Table 2). Our descriptive analysis showed that 81.5% of respondents spent their time on doing school work during the quarantine, followed by spending time with family (66.9%), communicating with friends online (66.9%), using online entertainment, that is, streaming videos, watching live concerts, or playing games (63.0%), and online surfing (57.1%). The top three channels that the respondents chose to stay connected with their loved ones (i.e., family, friends, and romantic partners) were texting (90.6%), phone calls (85.8%), and video calls/Facetime (83.9%). As to staying in touch with people at work, texting (39.8%), phone calls (30.3%), and face‐to‐face (28.7%) communication were the major channels. When it comes to staying connected with other people, social media (88.6%) was the most frequent communication tool.

Among the HBCU students, Instagram is the most popular social media: 92.5% of the respondents used Instagram to remain in contact with others, followed by Twitter (75.1%), Facebook (51.8%), Snapchat (51.8%), and Tik Tok (27.3%). On average, respondents spent more time with their family (M = 4.75, SD = 3.95), followed by friends (M = 4.47, SD = 3.47), and romantic partner (M = 4.07, SD = 4.89) than with co‐workers (M = 2.43, SD = 2.99) or other people in the world (M = 2.80, SD = 2.88).

4. DISCUSSION

Overall, this study contributes to the literature on emotional well‐being by exploring how active and healthy self‐care activities, perceived knowledge, and communication predict emotional well‐being during COVID‐19 among HBCU students and the mediating role of perceived control and social connectedness. The results suggest that emotional well‐being was predicted by the coping mechanism that promotes a strong sense of control and social connectedness, which mediated the impact of coping on emotional well‐being in times of uncertainty. When hit with a severe health outbreak, minority groups have the least social and economic means to protect themselves physically and mentally. However, the findings of the current study demonstrated that a strong sense of control in life during the pandemic play a key factor in maintaining HBCU student's emotional health despite the health threats and financial constraints.

4.1. Coping strategies, control, and emotional well‐being

Black college students who took self‐care measures that help occupy and stimulate one's mind, and enhance one's physical health, perceived greater sense of control and in turn, the sense of control they feel increases emotional well‐being. Specifically, when they looked after themselves by engaging in healthy and balanced self‐care, such as exercising, staying busy and keeping themselves entertained to take care of their body and mind, their sense of emotional well‐being was elevated. Prior studies have shown that active coping strategies that engaged in problem solving or support seeking, as well as self‐care daily activities or behaviors such as being outdoors and exercises undertaken to maintain one's physical, psychological, social and spiritual activities served as protective factors for positive emotional well‐being, life satisfaction, and resilience (Bermejo‐Martins et al., 2021; Y. Li et al., 2021; Mayordomo‐Rodríguez et al., 2015; Okabe‐Miyamoto & Lyubomirsky, 2021; Polizzi et al., 2020; Stieger et al., 2021), while emotion or avoidance‐based coping, as well as self‐medication (drug and alcohol) often are associated with negative psychological consequences (Dai et al., 2021; Hamilton et al., 2020; Kar et al., 2021; Prowse et al., 2021). Meanwhile, when HBCU students were actively engaging in their daily lives physically and emotionally, they felt more in control of things in their life, which in turn contributed to resilience and enhanced emotional well‐being. Overall, the finding points to the need for people to practice active or engaging coping strategies that allow people to live and appreciate life and to achieve adaptive coping in stressful circumstances. Further, the confidence that arises from one's abilities to utilizing coping resources in managing stress and online classes affords individuals higher level of control beliefs (Compas & Rutter, 1995; Dijkstra & Homan, 2016; Polizzi et al., 2020; Scott & House, 2005); in turn, perceived control mediated the adaptive coping on enhanced emotional well‐being (Dijkstra & Homan, 2016; Stupnisky et al., 2013; Yang & Ma, 2020; Yeo & Yap, 2020). When students believed that they were doing well in virtual learning, they perceived higher levels of control, consistent with prior work that found a high level of perceived academic control tends to be related to academic achievement (Stupnisky et al., 2012) and emotional well‐being (Stupnisky et al., 2013).

Further, as younger generations are spending more time online and doing less physical exercise with friends or online videos or other offline activities, the findings provide practical implications for mental health intervention to include a balanced combination program by emphasizing the behavioral activation components such as exercise and other indoor and outdoor activities which many college students are still lacking to stay busy and healthy. In addition, as young adults are still experiencing mental health problems, it may be helpful to offer workshops in providing coping strategies and stress management.

4.2. Coping strategies and social connectedness

Active self‐care coping also contributed to a strong feeling of social connectedness. To that extent, the Black college students feel more emotionally close and socially connected with others when they likely perform the following self‐care activities online or offline: (1) when they do exercises either through outdoor activities such as hiking and walking, or exercise with online videos, (2) when they engage themselves in other activities to stay busy (possibly including spending time with family, working on their job, doing school work, hanging out with friends and even reading books and articles), or (3) when they keep themselves entertained by watching streaming videos, playing video games, or communicating with their friends online (see Table 2). Apart from the face‐to‐face social interactions that take place in physical settings, the phenomena of para social interaction occurs when the individuals interact with the medium or the characters/actors/performers in the medium or online environment to feel the presence of the distant or virtual others and receive the experiences of social interaction similar to in‐person interaction to reduce loneliness during the pandemic (Onderdijk et al., 2021).

4.3. Knowledge

Knowledge plays an important role in facilitating positive mental health outcomes among African American college students during the pandemic. As fear and worry are known maladaptive responses to health outbreaks (Bonanno et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2011), our findings confirmed the health communication hypothesis that, in threatening and risky situations, people would feel the heightened need to seek information on the disease and prevention methods to stay in control (Case, 2002; Street, 2003) through perception of reduced likelihood of health risk and uncertainty (Bish & Michie, 2010; Eastwood et al., 2009). In turn the sense of control and empowerment contributed to greater well‐being. The results are further supported by literature indicating that feeling knowledgeable and well‐informed about the pandemic could have a buffering effect on emotional well‐being (i.e., decreased anxiety) during COVID‐19 (Jungmann & Witthöft, 2020), while extreme focus on the pandemic and excessive Internet search was often related to loss of control and more depressive mood (Dai et al., 2021).

When the results are being interpreted in the context of racial and age disparity in COVID‐19‐related knowledge, of which being African American and younger (55 and under) are among the less knowledgeable (Alobuia et al., 2020; Alsan et al., 2020; McCormack et al., 2021), the impact of perceived knowledge of emotional well‐being among African American college students proved to be particularly revealing and significant in predicting control and resulting emotional well‐being. With African Americans being disproportionately impacted by COVID‐19 and that more African Americans know other people who are infected (Alsan et al., 2020), perceived knowledge about COVID‐19 helped HBCU students gain a sense of control and feel better prepared for the worst health outcome of COVID‐19, which in turn, predicted better mental health.

4.4. Communication, social connectedness, and sense of control

Moreover, spending time communicating with people around you enhance perceived connectedness with others, and in turn, contributes to the feelings of being in control, which is the pathway to positive emotional well‐being. Connectedness refers to human's need for social contact and support. During the COVID‐19 lockdown, African American students were able to experience “staying alone together” by frequent communication with their friends and family, romantic partners, co‐workers and other people, which illustrates human's fundamental need for social interaction and emotional closeness to a wide range of social ties. With the popularity of social networking sites and personal devices such as mobile phones, tablets and personal computers, people can communicate from everywhere and with anyone who is not physically together with them. Thus, the key to mitigate loneliness could be through a combination of face‐to‐face and technology‐facilitated communication to stay connected with their loved ones, friends, classmates, co‐workers and people in the world, which could in turn contribute to a sense of social connectedness. Our findings are consistent with prior findings that the maintenance of social connections through the use of technology and in‐person interactions with a wide network of people within one's close and distant social relationships promoted social connectedness, reduced anxiety towards traumatic events, and benefited emotional health (David & Roberts, 2021; Holt‐Lunstad, 2018; Nitschke et al., 2021; Snyder‐Mackler et al., 2020), with a unique finding that the benefits of social connectedness to emotional well‐being is mediated through perceived control. Researchers who studied stress management during natural disasters, considered control and connectedness as the two Cs, in the 3C model of resilience (Reich, 2006). Our results provide evidence that frequent communication affords HBCU students the emotion closeness and support to perceive social connectedness with others which contributes to a critical sense of control one needs in times of adversity to stay emotionally well, particularly among those who were most affected by COVID‐19. On the other hand, if media use or social interactions are not used to facilitate meaningful communication, rather as an emotion‐focused coping to escape from the social reality, they may potentially hinder an individual's ability to cope with the negative consequence of COVID‐19 (Hudimova et al., 2021; Kar et al., 2021).

Further, taken the results into the cultural contact, African Americans are family oriented and value social connectedness within their social relationships. Despite the devastating effect of COVID‐19 on African Americans, many of them strive to maintain close social connections through face‐to‐face communication and use of technology. HBCU respondents spent significantly more time on communicating with family, friends, and romantic partners than with co‐workers and other people in general. In other words, they valued the social connections with their close ties more than the weak ties. The benefits of social connectedness however were taken together and had a wholistic impact on emotional health among HBCU students who experienced better mental health when they had frequent interaction with friends and family, as well as others during the lockdown (Nitschke et al., 2021; Rumas et al., 2021). As it was phrased in a health outbreak educational video, “Blacks in the United States have always had to stick together just to survive as a people” (i.e., collectivism) (Kreuter & McClure, 2004, p. 447), in times of challenges, African Americans tend to stick with their close ties in the community who share similar values and concerns, conducting more intensive contacts and supporting each other.

On the other hand, with the essential role social media play in young adults' lives and the vast amount of COVID‐19 information communicated on social media, African American young adults continued with their daily online routines and communicated with other people on social media to maintain their friendships and stay updated and fluid in their coping with the global pandemic. Although passive social media use has been suggested as having adverse effect on well‐being, other studies pointed to the social media's potential in producing positive influence. For instance, social media used to express emotions is associated with constructive growth, and social support received online is related to emotional well‐being during COVID‐19 among adults and college students (Canale et al., 2020). The results suggest the distinct and combined values of frequent communication and social support from the close and distant social relationships.

A further analysis into communication media use suggested a pattern of how individuals may utilize communication tool based on the types of relationships they have with the social others. For example, HBCU students predominantly used smart phone‐based features for communication with friends and friendly, such as texting, phone calls, and video calls/Facetime. With co‐workers, in addition to texting and phone calls, they also frequently used face‐to‐face communication as most students hold jobs as essential workers. On the other hand, social media, particularly Instagram and Twitter, were used for communication with people outside their inner circle and work. This finding can have implications for the media uses and gratifications among African American young adults.

4.5. Implications for community psychologists

The findings of the current study underscore the need for the development and implementation of culturally competent, community‐driven and mind−body balanced mental health programs targeting HBCU students as they may be uniquely disproportionately affected. Thus, there are several implications for community psychologists in how to approach HBCU students' mental health issues with respect to community/social togetherness, cultural competence, and self‐care programs. First, community psychologists could consider providing programs and activities aimed to facilitate social connection and social support through online and offline social interactions with close and distant others. Second, educating individuals and community about COVID‐19 and other health issues pertaining to African American communities. Lastly, implementing balanced and active self‐care programs to help individuals in the communities to stay active both physically and mentally, and ultimately gaining a strong sense of control and well‐being.

Future studies can replicate this study with students attending Hispanic‐serving institutions and minority students attending predominantly White institutions (PWIs) to deepen community psychologists' and mental health providers' understanding of within and between‐group similarities and differences for targeted prevention and intervention. Although it is difficult to predict if the results would be similar for other students with the same demographic profile as HBCU students, we anticipate that the results would be more applicable to students attending minority serving institutions and minority students attending PWIs as studies showed that students of color experienced higher level of stress, worsened emotional well‐being, and greater uncertainty toward their academic future than White students during the COVID‐19 pandemic (Chierichetti, 2020; Clabaugh et al., 2021; Lancaster & Arango, 2021). Not only are African Americans and Hispanic Americans disproportionately impacted by COVID‐19, they also suffer from chronic stress related to discrimination and share similar kinds of mental health stigmas and distrust of the medical system which prevented them from seeking mental health services. African Americans and Hispanic groups are more collectivistic, and their social‐cultural values place emphasis on social ties for well‐being (Spector, 2002); thus, social connection and communal coping are protective factors for general well‐being (Mulvaney‐Day et al., 2007).

4.6. Conclusion: Emotional well‐being among the HBCU students

Understanding how African American college students cope to preserve their emotional well‐being is particularly relevant as they continue to face the devastating impact of COVID‐19. Lessons from the study can inform public health campaign and education on coping strategies that are effective in targeting African American young adults, as well as the importance in improving knowledge of health outbreaks, and enhancing interpersonal communication through use of technology and in‐person settings.

Our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study that examined HBCU student's adaptive coping on emotional well‐being within the context of COVID‐19 pandemic. The results demonstrate the central role feelings of being in control play in linking adaptive coping including self‐care coping, COVID‐19 knowledge, communication, and social connectedness to African American college students' emotional well‐being. Meanwhile, social connectedness mediated the impact of communication on emotional well‐being through feelings of control in life, both of which were key contributors to resilience in stress coping. Some researchers believed control beliefs to be a common personal resource in developing resilience (Brissette et al., 2002; Taylor & Broffman, 2011). In the face of challenges and health threats, resilient individuals are more likely to find ways to regain a sense of control and their resilient personality may protect their psychological well‐being (e.g., Kumsta & Heinrichs, 2013; Taylor & Brown, 1988) even during the COVID‐19 lockdown, regardless of their ages (López et al., 2020).

When considering the lower knowledge level among young African Americans, their wholistic need for social connectedness, and the importance of healthy self‐care coping, a control‐centered coping mechanism seems particularly fitting and sensible in times of disproportionate adversity and uncertainty for African Americans. Finally, when healing and preservation rally around having a strong sense of control and social connectedness, it suggests the significance of control and social connectedness as psychosocial factors in protecting young African American from the impact of the social, physical, and psychological distress African Americans has endured as a vulnerable minority.

4.7. Limitations and directions for future study

Our study is timely and among the first to examine how self‐care coping measures, COVID‐19 knowledge, and communication with others contribute to perceived control and social connectedness, and in turn preserve the emotional well‐being of HBCU students during the extremely challenging pandemic. This study, however, is not without limitations. We used a convenience sample of the African American college students from an HBCU in the southeastern region of United States. To improve ecological validity, it would be helpful to study a wider range of respondents including other HBCU universities and colleges, as well as young adults from the local African American communities. In addition, future studies can consider examining gender differences in HBCU students' coping and emotional well. Lastly, even though our measures have proper internal consistency, future studies can identify additional items to enhance the reliability of the scales for coping strategies and for feeling in control in life.

Within the HBCU communities, social support with close ties or community‐based intervention featuring social support such as campus learning community could play a key role in their emotional well‐being. Future research can examine perceived or actual social support received as another active coping method to assess its role in improving emotional well‐being among HBCU students with quantitative and qualitative approaches. Qualitative research on the content of communications may be studied to discern the culturally salient nature of the communication. In addition, with African Americans' unique vulnerability to mental health issues during large‐scale health crisis and natural disasters, culturally sanctioned coping strategies that fall in line with African American's collective leaning minority culture and social identity should be considered as another protective factor for emotional well‐being (Novacek et al., 2020).

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

ETHICS STATEMENT

This study was approved by the appropriate institutional review board at the institution where the research was conducted. All participants received information about the study and gave their online consent before starting the survey.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/jcop.22824

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None of the authors was funded carry out the project.

Huang, H. Y. , Li, H. , & Hsu, Y.‐C. (2022). Coping, COVID knowledge, communication, and HBCU student's emotional well‐being: Mediating role of perceived control and social connectedness. Journal of Community Psychology, 50, 2703–2725. 10.1002/jcop.22824

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Available upon request.

REFERENCES

- Alobuia, W. M. , Dalva‐Baird, N. P. , Forrester, J. D. , Bendavid, E. , Bhattacharya, J. , & Kebebew, E. (2020). Racial disparities in knowledge, attitudes and practices related to COVID‐19 in the USA. Journal of Public Health, 42(3), 470–478. 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsan, M. , Stantcheva, S. , Yang, D. , & Cutler, D. (2020). Disparities in coronavirus 2019 reported incidence, knowledge, and behavior among US adults. JAMA Network Open, 3(6), e2012403. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.12403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez, J. , Snowden, L. R. , & Kaiser, D. M. (2008). The experience of stigma among Black mental health consumers. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 19(3), 874–893. 10.1353/hpu.0.0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA . (2020). Stress in America 2020. A.P. Association.

- Bermejo‐Martins, E. , Luis, E. O. , Fernández‐Berrocal, P. , Martínez, M. , & Sarrionandia, A. (2021). The role of emotional intelligence and self‐care in the stress perception during COVID‐19 outbreak: An intercultural moderated mediation analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 177, 110679. 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bish, A. , & Michie, S. (2010). Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. British Journal of Health Psychology, 15(Pt 4), 797–824. 10.1348/135910710x485826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. , Ho, S. M. , Chan, J. C. , Kwong, R. S. , Cheung, C. K. , Wong, C. P. , & Wong, V. C. (2008). Psychological resilience and dysfunction among hospitalized survivors of the SARS epidemic in Hong Kong: A latent class approach. Health Psychology, 27(5), 659–667. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.5.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond, B. J. (2021). Social and parasocial relationships during COVID‐19 social distancing. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(8), 2308–2329. [Google Scholar]

- Brissette, I. , Scheier, M. F. , & Carver, C. S. (2002). The role of optimism in social network development, coping, and psychological adjustment during a life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 102–111. 10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bzdok, D. , & Dunbar, R. I. (2020). The neurobiology of social distance. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24, 717–733. 10.1016/j.tics.2020.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, R. D. , & Mowbray, O. (2016). The stigma of depression: Black American experiences. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work: Innovation in Theory, Research & Practice, 25(4), 253–269. 10.1080/15313204.2016.1187101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canale, N. , Marino, C. , Lenzi, M. , Vieno, A. , Griffiths, M. , Gaboardi, M. , Cervone, C. , & Santinello, M. (2020). How communication technology helps mitigating the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on individual and social wellbeing: Preliminary support for a compensatory social interaction model. Journal of Happiness Studies , 10.1007/s10902-021-00421-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cao, W. , Fang, Z. , Hou, G. , Han, M. , Xu, X. , Dong, J. , & Zheng, J. (2020). The psychological impact of the COVID‐19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Research, 287, 112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C. S. , Scheier, M. F. , & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case, D. (2002). Looking for information: A survey of research on information seeking, needs, and behavior. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . (2020). COVID‐19 Hospitalization and Death by Race/Ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html [Google Scholar]

- Chierichetti, M. (2020). Understanding the role that non‐academic factors play on students' experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In 2020 IFEES World Engineering Education Forum‐Global Engineering Deans Council (WEEF‐GEDC) (pp. 1–5). 10.1109/WEEF-GEDC49885.2020.9293665 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clabaugh, A. , Duque, J. F. , & Fields, L. J. (2021). Academic stress and emotional well‐being in United States college students following onset of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 628787. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. , & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, S. E. , & Syme, S. (1985). Social support and health. Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Compas, B. E. (1995). Promoting successful coping during adolescence. In Rutter M. (Ed.), Psychosocial disturbances in young people: Challenges for prevention (pp. 247–273). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, R. C. , Koire, A. , Pinder‐Amaker, S. , & Liu, C. H. (2021). College student mental health risks during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Implications of campus relocation. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 117–126. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.01.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland, V. C. , & Snyder, K. (2011). Barriers to mental health treatment services for low‐income African American women whose children receive behavioral health services: An ethnographic investigation. Social Work in Public Health, 26(1), 78–95. 10.1080/10911350903341036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coster, J. S. , & Schwebel, M. (1997). Well‐functioning in professional psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, R. C. (1988). Perceptions of social support, receipt of supportive behaviors, and locus of control as moderators of the effects of chronic stress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 16(5), 685–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W. , Meng, G. , Zheng, Y. , Li, Q. , Dai, B. , & Liu, X. (2021). The impact of intolerance of uncertainty on negative emotions in covid‐19: Mediation by pandemic‐focused time and moderation by perceived efficacy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 4189. 10.3390/ijerph18084189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David, M. E. , & Roberts, J. A. (2021). Smartphone use during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Social versus physical distancing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(3), 1034. 10.3390/ijerph18031034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefendorff, J. M. , Richard, E. M. , & Yang, J. (2008). Linking emotion regulation strategies to affective events and negative emotions at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 73(3), 498–508. 10.1016/j.jvb.2008.09.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, M. T. M. , De Dreu, C. K. , Evers, A. , & van Dierendonck, D. (2009). Passive responses to interpersonal conflict at work amplify employee strain. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(4), 405–423. 10.1080/13594320802510880 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra, M. T. M. , & Homan, A. C. (2016). Engaging in rather than disengaging from stress: Effective coping and perceived control [Original Research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(1415), 1415. 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood, K. , Durrheim, D. , Francis, J. L. , d'Espaignet, E. T. , Duncan, S. , Islam, F. , & Speare, R. (2009). Knowledge about pandemic influenza and compliance with containment measures among Australians. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 87(8), 588–594. 10.2471/blt.08.060772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, S. J. , & Goodwin, A. D. (2010). Optimism and well‐being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 71(1), 43–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. (1984). Personal control and stress and coping processes: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 839–852. 10.1037/0022-3514.46.4.839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier, P. A. (2003). Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(6), 1257–1269. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, T. K. F. , Griffin, R. J. , & Dunwoody, S. (2018). Testing links among uncertainty, affect, and attitude toward a health behavior. Science Communication, 40(1), 33–62. 10.1177/1075547017748947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. L. , Nesi, J. , & Choukas‐Bradley, S. (2020). Teens and social media during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Staying socially connected while physically distant. Perspectives on Psychological Science . 10.31234/osf.io/5stx4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hartmann, T. (2016). Parasocial interaction, parasocial relationships, and well‐being. In The Routledge handbook of media use and well‐being: International perspectives on theory and research on positive media effects (pp. 131–144). Taylor and Francis Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Holt‐Lunstad, J. (2018). Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 437–458. 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hortop, E. G. , Wrosch, C. , & Gagné, M. (2013). The why and how of goal pursuits: Effects of global autonomous motivation and perceived control on emotional well‐being. Motivation and Emotion, 37(4), 675–687. 10.1007/s11031-013-9349-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, M. , Knottnerus, J. A. , Green, L. , van der Horst, H. , Jadad, A. R. , Kromhout, D. , Leonard, B. , Lorig, K. , Loureiro, M. I. , & van der Meer, J. W. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ, 343, d4163. 10.1136/bmj.d4163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudimova, A. , Popovych, I. , Baidyk, V. , Buriak, O. , & Kechyk, O. (2021). The impact of social media on young web users' psychological well‐being during the COVID‐19 pandemic progression. Amazonia Investiga, 10(39), 50–61. 10.34069/AI/2021.39.03.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzyna, C. L. (2021). Parasocial interaction, the COVID‐19 quarantine, and digital age media. Human Arenas, 4(3), 413–429. 10.1007/s42087-020-00156-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste, D. V. (2020). Coronavirus, social distancing, and global geriatric mental health crisis: Opportunities for promoting wisdom and resilience amid a pandemic. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1097–1099. 10.1017/S104161022000366X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, J. H. , Brosi, W. A. , Hermann, J. R. , & Jaco, L. (2011). The impact of social support on perceived control among older adults: Building blocks of empowerment. Journal of Extension, 49(5), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, J. , Sullivan, P. S. , Sanchez, T. H. , Guest, J. L. , Hall, E. W. , Luisi, N. , Zlotorzynska, M. , Wilde, G. , Bradley, H. , & Siegler, A. J. (2020). Similarities and differences in COVID‐19 awareness, concern, and symptoms by race and ethnicity in the United States: Cross‐sectional survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(7), e20001. 10.2196/20001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jungmann, S. M. , & Witthöft, M. (2020). Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID‐19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 73, 102239. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar, N. , Kar, B. , & Kar, S. (2021). Stress and coping during COVID‐19 pandemic: Result of an online survey. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113598. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KFF . (2020). Kaiser Family Foundation Poll: March 2020 Coronavirus Poll, March, 2020 (31117233; Version 2). The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, L. , Kearney, N. , O'Carroll, R. , & Hubbard, G. (2008). Experiences of self‐care in patients with colorectal cancer: A longitudinal study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(5), 469–477. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04796.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore, W. D. , Cloonan, S. A. , Taylor, E. C. , & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID‐19. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113117. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause, N. (1987). Understanding the stress process: Linking social support with locus of control beliefs. Journal of Gerontology, 42(6), 589–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreuter, M. W. , & McClure, S. M. (2004). The role of culture in health communication. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 439–455. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta, R. , & Heinrichs, M. (2013). Oxytocin, stress and social behavior: Neurogenetics of the human oxytocin system. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 23(1), 11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, M. E. (2006). Perceived control over aging‐related declines: Adaptive beliefs and behaviors. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(6), 282–286. 10.1016/j.conb.2012.09.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, M. , & Arango, E. (2021). Health and emotional well‐being of urban university students in the era of COVID‐19. Traumatology, 27(1), 107–117. 10.1037/trm0000308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]