ABSTRACT

Proper disinfection of harvested food and water is critical to minimize infectious disease. Grape seed extract (GSE), a commonly used health supplement, is a mixture of plant-derived polyphenols. Polyphenols possess antimicrobial and antifungal properties, but antiviral effects are not well-known. Here we show that GSE outperformed chemical disinfectants (e.g., free chlorine and peracetic acids) in inactivating Tulane virus, a human norovirus surrogate. GSE induced virus aggregation, a process that correlated with a decrease in virus titers. This aggregation and disinfection were not reversible. Molecular docking simulations indicate that polyphenols potentially formed hydrogen bonds and strong hydrophobic interactions with specific residues in viral capsid proteins. Together, these data suggest that polyphenols physically associate with viral capsid proteins to aggregate viruses as a means to inhibit virus entry into the host cell. Plant-based polyphenols like GSE are an attractive alternative to chemical disinfectants to remove infectious viruses from water or food.

IMPORTANCE Human noroviruses are major food- and waterborne pathogens, causing approximately 20% of all cases of acute gastroenteritis cases in developing and developed countries. Proper sanitation or disinfection are critical strategies to minimize human norovirus-caused disease until a reliable vaccine is created. Grape seed extract (GSE) is a mixture of plant-derived polyphenols used as a health supplement. Polyphenols are known for antimicrobial, antifungal, and antibiofilm activities, but antiviral effects are not well-known. In studies presented here, plant-derived polyphenols outperformed chemical disinfectants (i.e., free chlorine and peracetic acids) in inactivating Tulane virus, a human norovirus surrogate. Based on data from molecular assays and molecular docking simulations, the current model is that the polyphenols in GSE bind to the Tulane virus capsid, an event that triggers virion aggregation. It is thought that this aggregation prevents Tulane virus from entering host cells.

KEYWORDS: polyphenols, grape seed extract, human norovirus surrogate, Tulane virus, virus aggregation, molecular docking simulations

INTRODUCTION

Human noroviruses cause approximately 20% of all cases of acute gastroenteritis in developing and developed countries (1). In the United States, human noroviruses cause about 5.5 million cases of foodborne illnesses per year and about 2 billion dollars in economic loss (2, 3). Noroviruses are transmitted primarily by the fecal-oral route, including ingestion of contaminated food and water or via person-to-person contacts (4). Thus, inactivating human noroviruses present in contaminated food or water is important.

Sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) is regarded as the cheapest and most effective disinfectant to inactivate noroviruses on produce surfaces (5), stainless steel surfaces (6), or in liquid solutions (7). Fresh and fresh-cut produce are generally sanitized with residual chlorine concentrations of 50–200 μg/mL (8). Unfortunately, NaClO is toxic, and produces carcinogenic disinfection by-products (9–11). Thus, both consumers and industry are seeking methods to naturally or minimally processed foods with minimal/zero chemical additives (12, 13). Some organic compounds such as peracetic acid or vinegar have been studied as alternative disinfectants. Fuzawa et al. (2020) found that the Tulane viruses (TVs) were significantly more resistant to peracetic acid than rotaviruses because the TVs were aggregated due to the low pH of peracetic acid (i.e., pH 3). These authors concluded that further optimization is necessary to improve the inactivation efficacy (14). Five species of bacteria (C. albicans, S. mutans, S. aureus, E. coli, and B. subtilis) were treated with 100% vinegar for 10 min and 0.5 to 4.0-fold reduction in CFU/mL was found depending on bacteria species (15). However, vinegar's virucidal efficacy and mechanism have not been fully understood.

Plants and fruits synthesize polyphenols, chemicals that protect them against damage from external stresses such as infection. Grape seed extract (GSE), a by-product of grape juice and wine production, is mass-produced at an affordable price (16, 17). GSE is sold as an FDA-approved health supplement (18). GSE polyphenols have antimicrobial effects (19) and are considered popular alternatives to chemical disinfectants. GSE possesses antiviral activity against feline calicivirus (FCV-F9), murine norovirus (MNV-1), bacteriophage MS2, and hepatitis A virus (16, 20, 21). However, the mechanism of virus inactivation is unclear (18). This information is critical because, if GSE is to be used by industries as a natural disinfectant, then researchers must understand how GSE inactivates different types of viruses.

The objective of this study was to examine GSE-induced inactivation of TV, a surrogate for human norovirus. TV is an ideal surrogate for norovirus because of its structural similarities to human noroviruses (22–24). Thus, TV has been used to provide more information about the potential inactivation of norovirus (7, 14, 25–28). Once GSE disinfection was established, we identified the mechanism of this inactivation using both molecular assays and computer modeling. We found that GSE’s main disinfection action occurred due to virus aggregation. In addition, we conducted molecular docking simulations to identify potential interactions between GSE polyphenols and viral capsids. This study is the first observation that shows plant-derived polyphenols can outperform chemical disinfectants in safely and sustainably controlling waterborne and foodborne pathogens. This study also provides the mechanism for GSE-induced virus inactivation. Thus, GSE may be an attractive disinfectant for finished products such as drinking water and foods because of its safety, efficacy, and lower environmental impact.

RESULTS

GSE outperforms chemical disinfectants by 3-log10 TV titer reduction.

Fig. 1 shows results from the examination of disinfection properties of GSE against TV, using a range of different GSE concentrations, TV concentrations, and incubation times. For all experiments, GSE was incubated with purified TV. GSE activity was halted by the addition of FBS, and PFU were quantified as a measure of virus inactivation. We tested GSE concentrations ranging from 42 μg/mL to 678 μg/mL because similar GSE concentrations were shown to inactivate other enteroviruses (16, 20, 21).

FIG 1.

Inactivation effects of GSE on Tulane virus. (A) TV inactivation as a function of GSE concentration and time. 106 PFU Tulane virus was incubated with the indicated amount of GSE. FBS was added to quench each reaction at the indicated times. Initial virus titer (PFU0) was divided by the virus titer at each indicated time (PFU). Thus, the y axis (Log10PFU0/PFU) indicates the decrease in virus titer caused by GSE on log10 scale. For all experiments, each symbol represents one molecular replicate. The dashed lines were trend lines calculated by the pseudo-second-order model. (B) TV inactivation as a function of GSE concentration. In this experiment 106 PFU TV was incubated for 120 s with the indicated GSE concentrations. (C) TV inactivation as a function of initial TV titer. Varying amounts of TV (indicated on the x axis) were added to reactions containing 42 μg/mL GSE. All reactions were quenched with FBS after a 120 s incubation. (D) A comparison of GSE versus peracetic acid and free chlorine inactivation. 105 or 106 PFU TV was incubated with GSE (42 μg/mL) for 120 sec. The trend lines for GSE were determined by the pseudo-second-order model. The arrow indicates a detection limit. Trend lines for 42 μg/mL free chlorine or peracetic acid were derived by Chick’s law with the rate constants determined by our previous studies (7, 14).

TV inactivation increased when GSE concentration and duration of incubation increased (Fig. 1A). The inactivation curves were fitted to both the pseudo-second-order model and Chick's law. The correlation coefficients (R2 values), which reflect the goodness of fit, obtained by the pseudo-second-order model (0.99 to 1.00) were higher than those by Chick’s law (0.34 to 0.54) except for the lowest GSE concentration (42 μg/mL) where no significant reduction in virus titers was detected (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05). Parameters from the inactivation kinetics experiments are also listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The fitting to the pseudo-second-order model showed that it took less than 120 s to reach a 95% of log10 PFU reductions at equilibrium state (i.e., t95<120 s) for all tested conditions except for the 42 μg/mL case.

In Fig. 1A, better fitting achieved by the pseudo-second-order model suggested that chemisorption is the dominant reaction between the polyphenols and virus particles (29–31). This finding suggested there were optimal GSE:virion ratios for disinfection, as supported by data in Fig. 1B and C. Fig. 1B showed that TV inactivation increased as GSE concentrations increased, with GSE efficacy reaching a plateau at 424 μg/mL. This plateau in GSE efficacy suggests a maximum number of sites on the virions where GSE can bind to. Therefore, GSE concentration needs to be optimized for a given virus concentration. Fig. 1C showed that GSE disinfection efficacy significantly depended on the initial virus titer. Specifically, GSE disinfection efficiency decreased when more TVs were added to a reaction, supporting the hypothesis that chemisorption occurs between GSE and TV. Interestingly, while 42 mg/mL GSE showed no disinfection activity for 106 PFU TV (in Fig. 1A), it indeed possess antiviral properties when lower numbers of TV are present, further supporting the model that GSE polyphenols adsorb to TV surfaces. We compared GSE inactivation kinetics to those of two commercially available chemical disinfectants (i.e., free chlorine and peracetic acid) using a widely accepted disinfection model (i.e., Chick’s law) and the rate constants obtained from a previous study (7, 14) (red and green lines in Fig. 1D). We found 42 μg/mL of GSE inactivated the 105 PFU/mL of TV to a 3-log10 virus titer reduction within 16 s, a time identical to that of inactivation by free chlorine. In contrast, peracetic acid took much longer (211 s) to achieve the same levels of inactivation.

GSE causes viral aggregation, and this is likely the main mechanism of GSE-induced virus inactivation.

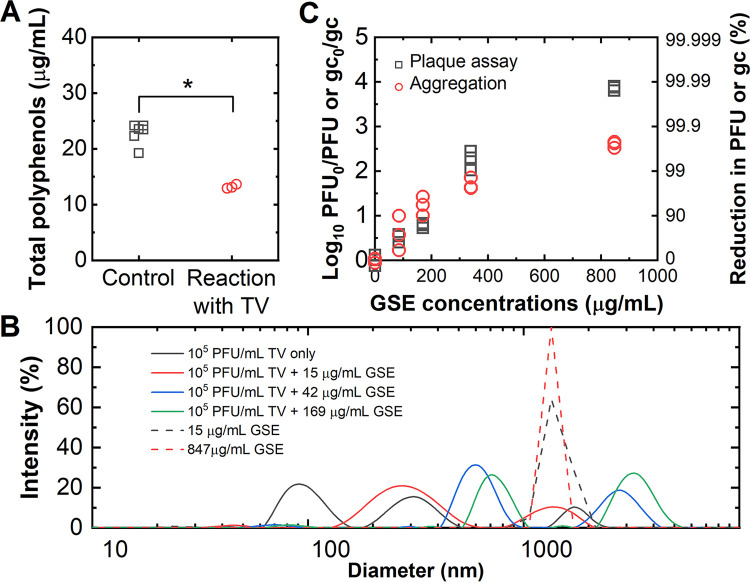

Fig. 1 data showed that GSE adsorbed to the virion surfaces and inactivated TV. Thus, one possibility is that GSE binds directly to TV to prevent virus-host interactions. Fig. 2A quantifies GSE polyphenols in the absence or presence of TV as a means to examine if GSE indeed binds to TV. We incubated 847 μg/mL GSE with 106 PFU TV. The 2 mL mixture was then subjected to ultracentrifugation to separate free versus virus-bound GSE, and GSE in supernatants of samples were quantified. As shown in Fig. 2A, there was a statistically lower GSE concentration in supernatants when TV was present, implying that GSE indeed binds to TV. Next, we used a light scattering analyzer (DelsaMax Pro, Beckman Coulter) to determine the particle size distributions of intact TV and GSE (Fig. 2B). Untreated TV showed a polydispersed multimodal size distribution with a major peak at 97 nm and two relatively smaller peaks at 309 and 1755 nm. A single TV virion has a diameter of 40 nm (32), thus most of the TVs in solution were present as dimers. Virus populations at 309 and 1755 nm were likely multi-virus aggregates. When TV was incubated with 15 μg/mL GSE, there was a shift in the size of the TV peak at 97 nm to approximately 300 nm and 1000 nm, implying that this concentration of GSE causes aggregation of TV into trimers and perhaps decamers. Experiments using higher concentrations of GSE resulted in greater shifts in sizes, suggesting that GSE is causing TV aggregation. GSE showed a strong single peak at around 1000 nm regardless of GSE concentrations. This peak is believed to represent insoluble polyphenols that are self-aggregated (33). When the GSE solutions were filtered with 0.1 μm filter, the monodispersed peak disappeared from the particle size distribution.

FIG 2.

GSE-induced TV aggregation. (A) Solutions either lacking (control) or containing 106 PFU TV were each incubated with 847 μg/mL of GSE followed by ultracentrifugation (150700 g) for 3 h. GSE concentrations were quantified, and statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney test (P < 0.05) (B) The particle size distribution of TV in the presence or absence of GSE. (C) A dose-response curve for plaque and aggregation assays. Plaque assay results were normalized to the initial virus titer and presented in Log10 PFU0/PFU to indicate the decrease in virus titer with different total polyphenol concentrations. Aggregation assay was analyzed by the one-step RT-qPCR and presented in the normalized gene copy number (Log10 gc0/gc) to show the reduction in the number of virions. Equivalent reductions in PFU or gc (%) were also presented on the right y axis for plaque assay and aggregation assay, respectively. For these experiments, 106 PFU TV was incubated with varying concentrations of GSE for 2 min followed by quenching the reaction with FBS. Each symbol indicates one separate experiment where one plaque assay or three qPCR analyses were conducted.

To further test if GSE induces virus aggregation, we quantified virus aggregation and virus titers in parallel and compared the numbers of virus aggregates and inactivated virus particles after the GSE treatment. As shown in Fig. 2C, 106 PFU TV was incubated with the indicated concentrations of GSE (85 to 847 μg/mL) for 2 min followed by quenching the reaction with FBS. Viruses were then either quantified by plaque assay or tested using an aggregation assay. Aggregation assays were designed as follows: untreated or GSE-treated TV were subjected to filtration using a 0.1 μm sized pore filter. Because a single TV virion has a diameter of 40 nm (32), we expect that single and dimeric TV would easily filter through the pore while virus aggregates with three or more virions would be trapped in the filter. Note that our aggregation assay cannot determine a specific number of virions in virus aggregates that can pass through the filter. Viruses that passed through the filter were quantified by one-step RT-qPCR. The ratio of genome copies for untreated versus treated viruses (Log10 gc0/gc) were plotted on the y axis in Fig. 2C. Similar to Fig. 1, plaque assays measured virus titers in untreated samples (PFU0) versus GSE-treated samples (PFU), and data are presented as the ratio of virus titers before and after exposure to GSE (Log10 PFU0/PFU) on the y axis in Fig. 2C. Virus aggregates and plaque were very similar when GSE concentrations below 400 μg/mL were used. However, virus aggregates were significantly lower than inactivated virus titers when 847 μg/mL GSE was present. This observed discrepancy shows that the number of virus particles larger than 0.1 μm does not fully explain the number of inactivated virus particles determined by the plaque assay. Nevertheless, paired t test revealed no significant difference between the plaque assay and aggregation assay results over the different GSE concentrations (P > 0.05). Thus, our current model is that GSE interacts with TV capsid, causing TV aggregation. In turn, aggregation would likely prevent TV from entering host cells. We also demonstrate that GSE aggregation was not reversible; removal of GSE from TV-containing solutions did not make aggregated TV return back into single particles (Text S1).

Molecular docking indicated polyphenols strongly bound to capsid proteins.

Data from Fig. 2 indicated that GSE is physically associated with TV and induced virus aggregation. This event likely prevents TV from entering the host cell to begin the virus life cycle. To further investigate this possibility, we conducted molecular docking simulations, an approach used to identify interactions between polyphenolic compounds and proteins (34, 35). GSE is a mixture of various polyphenolic compounds (36, 37). We selected 10 polyphenolic compounds present in GSE for molecular docking experiments. We chose these compounds based on abundance (37), which included two phenolic acids (gallic acid and protocatechuic acid), one stilbenoid (resveratrol), three monomer flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin, and epicatechin gallate), and four dimer flavan-3-ols (procyanidin B1, B2, B3, and B4). We detected those 10 polyphenolic compounds from the GSE using LC-MS metabolite profiling analysis and UHPLC-QqQ-MS analysis (Table S2 in the supplemental material). Although we conducted inactivation experiments using TV, we could not perform molecular docking simulations with the TV capsid because there is no entry for the TV capsid in the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/). However, Cryo-EM analysis has shown similarity between the TV and human norovirus (HuNoV) capsids (32), and the HuNoV capsid structure is present in the PBD. Thus, we studied the interaction of the GSE polyphenols with the HuNoV VP1 capsid proteins to understand how GSE may interact with similar TV capsid proteins.

We performed flexible molecular docking simulations (38, 39) between each of the 10 GSE polyphenolic compounds and HuNoV VP1 proteins to discern stable docking conformations across the four domains of VP1 (S, S-P1 hinge, P1, and P2 domain; Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) to identify where each of the polyphenols tended to bind in order of domain preference. For these simulations, we used the HuNoV icosahedral asymmetric unit (PDB ID: 1IHM) that comprised three VP1 proteins because the complete HuNoV capsid consists of 180 identical icosahedral asymmetric units. Residue-level domain definitions have been described by Campillay-Véliz et al. (40). Flexible molecular docking simulations are shown in Fig. 3. The expected binding strength of each polyphenol (in increasing order of molecular weight) with HuNoV capsid protein has been reported where the error bars indicate variance across top 15 polyphenol binding poses within the same capsid groove. The scale on the right indicates fractional capsid-binding affinity of a given polyphenol with respect to the positive control – BSA. Larger polyphenols tend to show increased affinity toward both the positive control and target capsid of HuNoV. Analysis of binding affinities from docking experiments reveals greater electrostatic stabilization of the larger conjugated electron systems within the bigger polyphenols by the polar grooves of HuNoV capsid and BSA alike. Data demonstrated that each of these 10 polyphenolic compounds likely bounds to different residues or regions of the HuNoV capsid protein. In addition, these polyphenols appeared to bind to a location at the dimeric interface of the trimeric capsid protein. The scores obtained from the simulation reflect the enthalpic contribution of binding (kcal/mol) between the polyphenols and the capsid (41). Fifteen independent trajectories of docking were performed using the docking protocol from OptMAVEn-2.0 suite (39) and the Rosetta energy function (42) was used to score the docked poses. The expected binding score was the modal value (i.e., most probable score) across the 15 recorded values per complex. Since the polyphenols tend to show a conjugated electron system, larger polyphenols showed better electrostatic stabilization by the polar binding groove offered by the capsid proteins. Consequently, flavan-3-ol dimers showed stronger binding affinities to the capsid protein than smaller groups of polyphenols (Fig. 3). The polyphenol-capsid interaction profiles were composed primarily of hydrogen bonds along with hydrophobic interactions, accounting for the efficient capsid capture seen in experiments (Fig. 4). For example, the smallest polyphenol protocatechuate establishes three hydrogen bonded and three hydrophobic contacts while procyanidin (the largest polyphenolic compound) shows up to 10 hydrogen bonded contacts yet maintaining the same number of hydrophobic interactions with the capsid (Fig. S3). In addition to being concordant with a previous experimental study showing that polyphenols’ binding affinity to proteins (e.g., BSA and human salivary α-amylase) increased with their molecular weights (43), we also provide key biophysical insights (Fig. 4). Binding affinities for respective polyphenols with the HuNoV capsid were near-equal to that of BSA, our positive control (Fig. 3). BSA is known as the major protein in FBS (44), with reported quenching activity toward polyphenolic compounds. Thus, our results indicated that the GSE polyphenols tend to promote capture of viral capsids with high efficiency.

FIG 3.

Summary of molecular docking analysis between HuNoV capsid and selected polyphenols found in GSE. BSA, which is known to bind strongly with polyphenols (16), was used as a positive control. The expected binding strength of each polyphenol (in increasing order of molecular weight) with HuNoV capsid protein (PDB id: 1IHM) has been reported where the error bars indicate variance across top 15 polyphenol binding poses within the same capsid groove. The scale on the right indicates fractional capsid-binding affinity of a given polyphenol with respect to the positive control – BSA.

FIG 4.

Larger polyphenols show greater electrostatic stabilization with the viral capsid. (A) HuNoV capsid shows a trigonal-symmetric polyphenol accessible groove (indicated in teal), which includes three intra-chain pockets, and three inter-chain binding crevices. Smaller polyphenols can access the inter-chain crevices, while the bigger ones remain localized to the more solvent-exposed intra-chain pockets. (B) Residue level interactions of Procyanidin-B1 with the HuNoV capsid are listed. (C) A graphical overview of the exact docked pose of Procyanidin-B1 in the capsid groove with most of the interactions is illustrated.

It is noteworthy that as the size of the polyphenol increases, it tends to bind to a less-buried, more solvent-exposed pocket (owing to steric clashes) (Fig. 5) yet binding to the interface of two chains of the trimeric capsid (located around the S-P1 hinge domain; Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Only the largest Procyanidin (B1-B4) polyphenols cannot access the inter-chain interface pockets and are primarily surface binders with most interactions limited to a single chain (Fig. 5). We thereby hypothesize that larger polyphenols tend to be surface binders but stronger capsid binders, while smaller ones preferably bind to inter-chain interfaces of the viral capsid. In terms of domains bound, our docking simulations, in concordance with the experimental data, show that most polyphenols bind to the S or S-P1 hinge domains, while trace binding is observed in the P1 domain and P2 domain is mostly unbound.

FIG 5.

All polyphenol binding is primarily localized around the S and S-P1 hinge domains of the HuNoV capsid, while the P2 domain remains mostly unbound. Smaller polyphenols can access more buried inter-chain pockets of the HuNoV capsid, while larger Procyanidins bind to surface-exposed pockets with a single chain. Pockets guarded by each chain have been indicated by a different color (green – A, cyan – B, magenta – C). Smaller polyphenols – protocatechuate, gallate, and catechin bind best at the interface of chains B and C. Slightly larger epicatechin and epicatechin gallate bind best at the interface of chain A and B, while larger procyanidins (all B1 through B4) bind best to a solvent-exposed cavity within chain A only.

We extended the molecular docking simulations to other enteric viruses such as feline calicivirus (FCV-F9), murine norovirus (MNV-1), and hepatitis A virus (HAV) that were experimentally studied in previous works (16, 20, 21). Although the three sets of experiments were performed in different conditions, such as different virus media (water or produce) and different pH, they presented a similar trend that FCV-F9 is more susceptible to the polyphenols in GSE than MNV-1 and HAV. Our molecular docking simulation agreed with the experimental data with these enteric viruses. The binding energy of the polyphenols to FCV-F9 capsid protein was stronger than those of MNV-1 and HAV (P < 0.05) (Fig. 6). Note that the binding energy alone does not give sufficient information to evaluate the antiviral effect of the polyphenols. Therefore, in vitro experiments are still required to determine virus inactivation efficacy and mechanisms.

FIG 6.

Expected binding energies (absolute modal values) between each polyphenolic compound and the four viral capsids (HuNoV: human norovirus, FCV: feline calicivirus F9, MNV: murine norovirus strain 1, and HAV: hepatitis A virus) were computed using the Rosetta binding energy function from top 15 docking poses per complex. The error bars indicate variance from the 15 docked poses for each complex. The reported energy scores were compared by a paired sample t test indicating a statistically significant higher polyphenol binding activity by HuNoV and FCV in contrast to MNV (P < 0.05) and HAV (P < 0.001) capsids.

DISCUSSION

Anti-bacterial, anti-biofilm, and antifungal effects of plant-derived polyphenols are well-known. In this study, we systematically evaluated the antiviral efficacy and mechanism of the polyphenols in GSE to TV, a surrogate virus for HuNoV. Data shown here suggest that GSE can inactivate TV and perhaps other enteric viruses. In addition, data show that the polyphenols in GSE aggregate the virus particles, an event that is likely responsible for TV inactivation. Indeed, high binding energies between polyphenols and capsid proteins calculated by molecular docking analysis supported the GSE-induced TV aggregation (Fig. 6). Our current model is that TV aggregation prevents proper virus-host interactions or virus entry into host cells. At least one other study has reported that aggregation of herpes simplex virus prevents virus entry into cells while allowing virus attachment (45).

We found antiviral efficacy of GSE depends on initial virus titers. It should be noted that the TV concentrations used in this study are likely much higher than those found in contaminated produce or water. For example, rotavirus concentrations in river water, treated wastewater, and untreated wastewater are reported to be 10−3.0, 10−2.2, and 10−1.3 FFU/mL, respectively (46, 47). Given that GSE was efficacious for these artificially high TV concentrations in the experiments presented here, it is reasonable to expect that GSE would be effective as an antiviral material for contaminated food or produce. Also, TV is more resistant to chemical disinfectants than the other viruses in the Caliciviridae family (48). Thus, it is likely that GSE would be efficacious against other caliciviruses, and this is an avenue of future research. GSE is also attractive because it has been approved for consumption by humans. Thus, GSE or plant-derived polyphenols could be advantageous over the chemical disinfectants for drinking water and foods.

The experiments conducted in this study have several limitations. Thus, further research is necessary before GSE is widely used to inactivate waterborne and foodborne pathogens. First, GSE consists of numerous polyphenolic compounds at different concentrations, and its constituents depend on various factors such as grape species, cultivation regions, and extraction methods. Therefore, GSE products may have different polyphenol compositions and antiviral efficacy. We did not perform inactivation experiments with single polyphenol compounds, which is important information to estimate the antiviral efficacy of the other GSE products. Future studies could perform a set of inactivation experiments with purified polyphenol compounds and determine their contributions to antiviral activity. Second, we conducted only in vitro experiments, and in silico analyses, so a future direction is to identify the effective dosage of GSE (and its active compounds) to begin to understand the actual mode of action in detailed mechanisms. In addition, although GSE is a health supplement approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), its side effects cannot be ignored. For example, GSE might enhance antiplatelet effects when combined with other supplements (49). Finally, water contains other organic matter which could outcompete viruses for binding to polyphenolic compounds. For example, Joshi et al. (16) showed that the antiviral efficacy decreased when milk with high protein content was added to an inactivation reaction. Thus, further studies need to be performed to understand how effective GSE is in water with different compositions and under various physical conditions. Other water properties (e.g., pH, ionic strength, and temperature) are important for adsorption reactions, and additional studies need to address how these properties may affect the efficacy of GSE. If GSE or individual polyphenols were to be used for foods (e.g., apples) then we must also understand how the surface properties of foods (e.g., wax contents of produce surface) may affect the efficacy of GSE (14).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Commercially available grape seed extract and its plant-derived polyphenols.

We purchased a commercial grape seed extract (GSE) solution for this research (7832, Natures plus, USA). The total polyphenol (TP) concentration in each GSE sample was quantified by the colorimetric method using Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. A mixture of 100 μL GSE sample and 500 μL of 10% Folin-Ciocalteu phenol reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) was prepared in a 10 mm path length polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cuvette (BrandTech Scientific, CT, USA). Within 3 to 8 min of mixture preparation, 400 μL of 7.5% sodium carbonate solution was added to the mixture and homogenized by pipetting. After incubating at room temperature for 60 min, UV absorbance at 765 nm was measured by a spectrophotometer (UV-2450, Shimadzu, Japan). Distilled water was used as a reference solution. The same procedure was conducted with gallic acid solutions with different concentrations prepared by diluting gallic acid monohydrate (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) in distilled water. The TP concentrations of the gallic acid solutions were used for a calibration curve (Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) which determined TP concentration of the GSE samples. GSE concentrations ranging from 84 to 1694 μg/mL were prepared by diluting the initial GSE from 25-fold to 500-fold with 1X PBS and used for inactivation experiments. PBS is widely used as a vehicle for in vitro virus experiments (7, 28, 50). Note that the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent can react with any reducing substances other than polyphenols. We applied the same colorimetric method to TV solutions and found that virus concentrations of 106 PFU/mL, the highest virus titer used in this study, are equivalent to 18 ± 1 μg/mL of GSE concentration. To exclude the impact of TV on GSE concentration determination using this assay, we determined GSE concentration by multiplying the initial GSE concentration, which did not contain TV, by dilution factors.

GSE and four standard compounds (catechin, procyanidin B2, gallic acid, and resveratrol) were analyzed with the Triple 6500+ LC/MS/MS system (Sciex, Framingham, MA) in Metabolomics Lab of Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Software Analyst 1.7.1 was used for data acquisition and analysis. The 1260 infinity II HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) includes a degasser, an autosampler, and a binary pump. The LC separation was performed on an Agilent SB-Aq column (4.6 × 50 mm, 5 μm) with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The flow rate was 0.3 mL/min. The linear gradient was as follows: 0-2min, 95%A; 10-15min, 0%A; 15.1-20min, 95%A. The autosampler was set at 10°C. The injection volume was 10 μL. Mass spectra were acquired under negative electrospray ionization (ESI) with the ion spray voltage of -4,500 V. The source temperature was 400°C. The curtain gas, ion source gas 1, and ion source gas 2 were 35, 50, and 65 lb/in2, respectively. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was used for quantitation: gallic acid (from m/z 169.0 to m/z 79.0), catechin (from m/z 289.0 to m/z 205.0), procyanidin B2 (from m/z 577.2 to m/z 299.0); resveratrol (from m/z 277.0 to m/z 185.0).

We also characterized the GSE using UHPLC-QqQ-MS with four standard compounds of catechin, procyanidin B2, gallic acid, and resveratrol. We chose these four compounds to represent each subgroup of polyphenols (i.e., monomers flavan-3-ol, dimers flavan-3-ol, phenolic acid, and stilbenes). We discovered catechin, procyanidin B2, gallic acid, and resveratrol account for 5.97, 2.96, 0.67, and 0.001% of total polyphenols in the GSE. Although we could not quantify every single polyphenolic compound, our analysis suggests that flavanols are the major polyphenols in the GSE. With the mass spectrometry and the references characterizing polyphenols in GSE, we chose 10 target polyphenolic components, which include three monomers flavan-3-ols (catechin, epicatechin, and epicatechin gallate), four dimers flavan-3-ols (Procyanidin B1, Procyanidin B2, Procyanidin B3, and Procyanidin B4), two phenolic acid (gallic acid and protocatechuic acid), and one stilbene (resveratrol). These 10 polyphenolic compounds were further studied through molecular docking simulations.

TV propagation.

TV was used as a surrogate for human norovirus (HuNoV). Both TV and HuNoV are members of Caliciviridae and share structural similarities. TV and HuNoV have a positive-sense, single-stranded genomic RNA of 6.7 kb and 7.5 kb, respectively. About 23–26% of the genome sequences are identical in both viruses (22). The capsid of TV has T = 3 icosahedral symmetry and is 40 nm in diameter. The capsid comprises 180 copies of major capsid protein (VP1) or 90 dimers of A/B or C/C. The VP1 is also sub-divided into S, P1, and P2 domains. When the VP1 proteins are assembled, the S domains comprise the bottom surface of the capsid while P1 and P2 domains protrude out of the bottom surface, which is responsible for binding to receptor proteins (Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Similar to HuNoVs, TV recognizes Histo-blood group antigens (23) and sialic acids (24) as cellular receptors. TV is considered more resistant to disinfectants than the other viruses in Caliciviridae (48). Therefore, TV has been widely used in virus inactivation experiments as a surrogate for HuNoVs (7, 14, 25–28).

TV was a gift from Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (24) and the TV genome was sequenced as quality control. The genome sequence was 100% identical to those of a wild-type TV strain in GenBank (accession number: EU391643) (7). TV was propagated in MA104 cells, which was purchased from ATCC (CRL-2378.1), and grown in complete culture medium (i.e., 1X minimum essential medium (MEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 1X antibiotic-antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 17 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). When greater than 90% of MA014 cellular monolayers showed cytopathic effects (about 2 days after the inoculation), cells were harvested and collected by centrifugation, and TV was released from host cells by three cycles of freeze and thaw. Virus was separated from cellular debris by centrifugation at 2000 rpm (556 g) for 10 min (Sorvall Legend RT Plus, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The supernatant was treated by filtration with a 0.22 μm bottle top filter (Milliporesigma, USA) to remove additional cellular debris. The virus-containing filtrate was then further purified using an ultracentrifuge (Optima XPN-90 Ultracentrifuge, Beckman Coulter, USA) with a cycle of 1,000 rpm (116 g) for 5 min followed by 36,000 rpm (150,700 g) at 4°C for 3 h. The virus pellet was resuspended in 1X PBS, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C before use.

TV inactivation experiments using GSE.

Virus inactivation experiments were initiated by adding 250 μL of TV solution containing 2.5 × 105 PFU TV to 250 μL of GSE-containing solution, in which GSE concentrations ranged from 84 to 1694 μg/mL. After the incubation times indicated in the manuscript (i.e., 10 to 120 s), 70 μL of the mixture was added to 70 μL of FBS to quench the polyphenolic activity (16). Thus, the volumetric ratio of TV, GSE, and FBS in the final solution was 1:1:2. The FBS quenching activity was confirmed in Fig. S5 in the supplemental material. Negative controls were prepared for every virus inactivation experiment. In this case, the negative controls were prepared by mixing TV, GSE, and FBS in the ratio of 1:1:2, but in a different mixing order. Specifically, 35 μL of GSE was mixed with 70 μL of FBS to quench the polyphenolic activity followed by adding 35 μL of TV to the mixture (Fig. 1A). The final mixture of TV, GSE, and FBS was used for further analysis.

Plaque assays.

The MA104 cell line was grown in 175 cm2 flasks (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the complete culture medium. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (CC7682-7506, USA Scientific, USA) resulting in cellular monolayers with more than 90% confluence. Cell culture supernatants were aspirated using a vacuum-connected pasteur pipette. 100 μL of TV samples were serially diluted by 10-fold. Cellular monolayers were incubated with each of the serially-diluted viruses for 1 h at 37°C with 5% CO2 to facilitate virus attachment to the MA104 cells. Viruses were aspirated from cellular monolayers and 2 mL of overlay solution containing 1X MEM, 1% agarose, 7.5% sodium bicarbonate, 15 mM HEPES, and 1X antibiotic-antimycotic was added to each well. The overlay solution was solidified at 4°C for 10 min. Plates were incubated for 2 days at 37°C with 5% CO2 to allow infectious viruses to form plaques. Next, 2 mL of 10% formaldehyde (VWR, USA) in 1X PBS was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 h to fix cells. The agarose and the formaldehyde were removed and replaced with a 0.05% crystal violet dye solution. The solution was washed away after 10 min, and the number of PFU was counted on a lightbox (ULB-100, Scienceware). The detection limit of the plaque assay was one plaque on the least diluted sample (i.e., 10-fold dilution), which was equivalent to 101.1 PFU/mL.

Models for virus inactivation kinetics.

TV inactivation kinetics were interpreted by a first-order reaction of Chick’s law (equations 1–3) and pseudo-second-order model (equations 4–6). Chick’s law assumes the activity (i.e., concentration) of available disinfectant remains constant during the reaction. Chick’s law has been widely used to describe virus inactivation kinetics by free chlorine, peracetic acid, monochloramine, heat, ozone, and UV (7, 51–54).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Where N referred to viral infectivity (PFU/mL), c indicated the TP concentration (μg/mL), t was treatment time (s), k' meant an inactivation rate constant from Chick’s law (mL/μg·s).

The pseudo-second-order model has been widely used to describe reactions where chemisorption between adsorbent and adsorbate is the rate-determining step (29). In this study, TV and TP were considered as adsorbate and adsorbent, respectively.

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

Where t is the reaction time (s), k2 is the rate constant from the pseudo-second-order model (mL/PFU times s), Ct and Ce are inactivated TV concentration (PFU/mL) at time t and equilibrium state, respectively. Also, t95% is a reaction time at which Ct reaches 95% of Ce.

Virus particle size.

The particle size distribution of TV was measured by a light scattering analyzer (DelsaMax Pro, Beckman Coulter). TV, GSE, and FBS, either alone or in combination, were prepared in 200 μL aliquots, placed in a PMMA cuvette (BrandTech Scientific, USA). Particle size was measured 20 times for each sample, and the averaged % intensity was presented with the particle diameter. According to the manufacturer, particle size analysis is reliable within a range from 0.4 to 10,000 nm, and all our measurements were in this detection range.

Virus aggregation assay.

An assay was developed to quantify TV virions that are less than 100 μm in diameter. After the TV inactivation experiments were conducted, the mixture containing viruses, GSE, and FBS was filtered with a 0.1 μm syringe filter (Sartorius, Germany). The number of virus particles in the initial mixture and the filtrate was quantified by one-step RT-qPCR. RNA was extracted from samples using Viral RNA minikit (Qiagen, Germany) in a final 60 μL volume. RT-qPCR samples were prepared in 96-well plates (4306737, Applied Biosystems, USA) by mixing 5 μL of 2 × iTaq universal SYBR green reaction mix, 0.125 μL of iScript reverse transcriptase from the iTaq universal SYBR green reaction mix (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA), 3 μL of the RNA, 0.3 μL of 10 μM TV-NSP1-qPCR-F primer, 0.3 μL of 10 μM TV-NSP1-qPCR-R primer, and 1.275 μL of nuclease-free water. The one-step RT-qPCR was run using a qPCR system (QuantStudio 3, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) with the following thermocycle: 10 min at 50°C and 1 min at 90°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 60°C and 1 min at 90°C. Detailed information for primers and synthetic DNA controls is summarized in Table 1. We obtained a calibration curve by plotting the viral infectivity (Log10 PFU/mL) on the x axis and the outcome of the one step RT-qPCR assay (Log10 gc/mL) on the y axis for the same viral solution (Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The calibration curve was used to determine the reliable range of the aggregation assay. The calibration curve for the aggregation assay was linear (a slope = 0.95 and R2 = 1.00) between 103 and 107 PFU/mL. The PCR standard curves were obtained with 10-fold serial dilutions of the synthetic DNA oligonucleotide (Integrated DNA technologies, USA) and the PCR efficiency for this one-step RT-qPCR ranged from 85% to 95% (R2>0.99). Inhibitory effect of GSE was also tested (Fig. S7). We found 100-fold dilution can reduce the inhibitory effect of GSE to an insignificant level, so the samples were diluted in molecular grade water by 100-fold before the RT-qPCR analysis. Information for RT-qPCR was summarized following the MIQE guidelines (55) in Table S3.

TABLE 1.

Information for RT-qPCR conditions and primersa

| Process | Primer name | Sequence (5′–3′) | Position in the genome | Amplicon length (bp) | Reaction conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | TV-NSP1-qPCR-F | GTGCGCATCCTTGAGACAAT | 879-899 | 132 | 50°C for 10 min and 95°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of (95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 30 s) |

| TV-NSP1-qPCR-R | TTGGAGCCGGGTAGAAACAT | 991-1011 |

Primer pair specificity was checked by the primer-blast tool (National Center of Biotechnology Information). Each pair of primers were blasted with Rhesus monkey (taxid:9544) which was the host organism. As a result, we confirmed that our primers did not target any sequences of the MA104 cells. The sequence of standard sample for the NSP gene of TV (Integrated DNA technologies, USA): 5′-AGAATTGGACCGAATTTGGCACACACTCAGAATTTGGTGTGCGCATCCTTGAGACAATAACAGGCACAATACCCCCTTGGAAACCTCACCAGGAATCAATATCTGAAGTTCTGGACGACCTCACACACGGTAAAGTCCAAACAGGTGATGATGTTTCTACCCGGCTCCAAAGGTTGAGCGACACTATCAAAGATCTGAGTGTCATGGCTTGTGATCCCTCTGCACCGCCCGAAGTTGCGC-3′ (GenBank accession number: EU391643).

One concern for the aggregation assay was that diluting GSE concentrations and vortexing virus solutions could reverse the aggregation effects induced by GSE, resulting in virus segregation (56–59). Thus, we performed an experiment where TV was inactivated by 847 TP-μg/mL of GSE, which was the highest GSE concentration for the virus aggregation assay (Fig. 1B), and subsequently quenched by FBS. Next, samples were serially diluted in complete culture media and vortexed for 10 s. These serial dilutions were examined by one-step RT-qPCR to determine the total number of virions regardless of aggregation induced by GSE. Each serial dilution was then subjected to filtration, using filters with a 0.1 μm size pore. The filtrates were also quantified by one-step RT-qPCR to determine the number of virions that passed through the 0.1 μm filter. The differences in the RNA copies after the filtration indicate the number of virion aggregates with a diameter of larger than 0.1 μm after dilution and vortexing. Detailed information on the experiment is elaborated in Text S1.

Molecular docking simulation for polyphenols and capsid proteins interaction.

We selected 10 polyphenolic compounds that are present in GSE, including one stilbene, two phenolic acids, three monomer flavan-3-ols, and four dimer flavan-3-ols (37). The structural information on the polyphenols were obtained from PUBChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Although we conducted inactivation experiments with TV, we obtained HuNoV capsid protein instead of TV from the Protein Data Bank (PDB, https://www.rcsb.org/) to study interactions with the polyphenols because the database of PDB does not provide TV capsid information. Cryo-EM structure analysis showed that the TV capsid structure closely resembles that of HuNoV (32).

We downloaded the HuNoV icosahedral asymmetric unit (PDB ID: 1IHM) which is a basic building block for the HuNoV capsid. This icosahedral unit comprises three VP1 proteins (i.e., chain A, B, and C in PDB format). The complete HuNoV capsid consists of 180 identical icosahedral asymmetric units. We also used a deep-learning-based structure prediction tool, trRosetta (60), to predict the 3D-structure of the TV capsid (Supplemental File 2) from its sequence and a multiple-sequence alignment of related sequences. We studied molecular docking of the polyphenols to HuNoV and to other different enteric viruses including hepatitis A virus (PDB: 4QPI), murine norovirus-1 (PDB: 6S6L), and feline calicivirus-F9 (PDB: 6GSH). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) is a major component for FBS, and BSA showed a strong binding affinity to the polyphenols as confirmed by the quenching effect in the virus inactivation experiments. BSA (PDB: 4F5S) was used as a positive control for molecular docking with the polyphenolic compounds. Next, we used the target proteins (capsids or BSA) and flexible conformations of all the aforementioned 10 polyphenol ligands to discern stable docking conformations, record binding affinity scores, and report across four capsid domains where each of the polyphenols tend to bind in order of domain preference. The flexible docking protocol is similar to the Z-Dock protocol (38) as implemented within OptMAVEn-2.0 (39).

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were repeated three times with distinct virus samples (i.e., three biological replications), each of which was analyzed by three separate RT-qPCR measurements (i.e., three technical replications). Paired sample t test was used to compare results of plaque assay and aggregation assay in Fig. 2C and binding energies of different viral species (HuNoV, FCV, MNV, and HAV) to polyphenolic compounds in Fig. 6. We confirmed that all data for statistical analysis satisfied assumptions of paired sample t test (i.e., no outliers and normality). For example, all data for statistical analysis were between Q1-1.5IQR and Q3 + 1.5IQR range, which means there were no outliers. Also, differences between two data sets (e.g., plaque assay versus aggregation assay in Fig. 2C or HuNoV versus MNV or HAV in Fig. 6) were normally distributed (P > 0.05).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by National Science Foundation (Award Number: 2023248). We thank Kang-Mo Ku at the Chonnam National University and Zhong (Lucas) Li at Metabolomics Lab, Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for characterizing polyphenolic compounds in grape seed extract.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Thanh H. Nguyen, Email: thn@illinois.edu.

Nicole R. Buan, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmed SM, Hall AJ, Robinson AE, Verhoef L, Premkumar P, Parashar UD, Koopmans M, Lopman BA. 2014. Global prevalence of norovirus in cases of gastroenteritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 14:725–730. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70767-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. 2011. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States-Major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 17:7–15. 10.3201/eid1701.p11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burke RM, Mattison CP, Pindyck T, Dahl RM, Rudd J, Bi D, Curns AT, Parashar U, Hall AJ. 2020. Burden of norovirus in the United States, as estimated based on administrative data: updates for medically attended illness and mortality, 2001–2015. Clin Infect Dis 73:e1–e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bitler EJ, Matthews JE, Dickey BW, Eisenberg JNS, Leon JS. 2013. Norovirus outbreaks: a systematic review of commonly implicated transmission routes and vehicles. Epidemiol Infect 141:1563–1571. 10.1017/S095026881300006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraisse A, Temmam S, Deboosere N, Guillier L, Delobel A, Maris P, Vialette M, Morin T, Perelle S. 2011. Comparison of chlorine and peroxyacetic-based disinfectant to inactivate Feline calicivirus, Murine norovirus and Hepatitis A virus on lettuce. Int J Food Microbiol 151:98–104. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girard M, Ngazoa S, Mattison K, Jean J. 2010. Attachment of noroviruses to stainless steel and their inactivation, using household disinfectants. J Food Prot 73:400–404. 10.4315/0362-028X-73.2.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuzawa M, Araud E, Li J, Shisler JL, Nguyen TH. 2019. Free chlorine disinfection mechanisms of rotaviruses and human norovirus surrogate Tulane virus attached to fresh produce surfaces. Environ Sci Technol 53:11999–12006. 10.1021/acs.est.9b03461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Hung YC. 2016. Predicting chlorine demand of fresh and fresh-cut produce based on produce wash water properties. Postharvest Biol Technol 120:10–15. 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2016.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parish ME, Beuchat LR, Suslow TV, Harris LJ, Garrett EH, Farber JN, Busta FF. 2003. Methods to reduce/eliminate pathogens from fresh and fresh-cut produce. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Safety 2:161–173. 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2003.tb00033.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soto Beltran M, Jimenez Edeza M, Viera C, Martinez CI, Chaidez C. 2013. Sanitizing alternatives for Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium on bell peppers at household kitchens. Int J Environ Health Res 23:331–341. 10.1080/09603123.2012.733937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matulonga B, Rava M, Siroux V, Bernard A, Dumas O, Pin I, Zock JP, Nadif R, Leynaert B, Le Moual N. 2016. Women using bleach for home cleaning are at increased risk of non-allergic asthma. Respir Med 117:264–271. 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland J, Montville TJ, Nes IF, Chikindas ML. 2001. Bacteriocins: Safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation. Int J Food Microbiol Elsevier 71:1–20. 10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devlieghere F, Vermeiren L, Debevere J. 2004. New preservation technologies: possibilities and limitations, p 273–285. International Dairy Journal 14: 273–285. 10.1016/j.idairyj.2003.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuzawa M, Bai H, Shisler JL, Nguyen TH. 2020. The basis of peracetic acid (PAA) inactivation mechanisms for rotavirus and Tulane virus under conditions relevant for vegetable sanitation. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e01095-20. 10.1128/AEM.01095-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Da Silva FC, Kimpara ET, Mancini MNG, Balducci I, Jorge AOC, Koga-Ito CY. 2008. Effectiveness of six different disinfectants on removing five microbial species and effects on the topographic characteristics of acrylic resin. J Prosthodont 17:627–633. 10.1111/j.1532-849X.2008.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi SS, Su X, D'Souza DH. 2015. Antiviral effects of grape seed extract against feline calicivirus, murine norovirus, and hepatitis A virus in model food systems and under gastric conditions. Food Microbiol 52:1–10. 10.1016/j.fm.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Research and Markets. 2019. Polyphenols market size, share & trends analysis report by product (grape seed, green tea, cocoa), by application (beverages, food, feed, dietary supplements, cosmetics), and segment forecasts, 2019–2025. Research and Markets, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Memar MY, Adibkia K, Farajnia S, Kafil HS, Yekani M, Alizadeh N, Ghotaslou R. 2019. The grape seed extract: a natural antimicrobial agent against different pathogens. Rev Med Microbiol 30:173–182. 10.1097/MRM.0000000000000174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Souza DH. 2014. Phytocompounds for the control of human enteric viruses. Curr Opin Virol 4:44–49. 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su X, D'Souza DH. 2011. Grape seed extract for control of human enteric viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:3982–3987. 10.1128/AEM.00193-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su X, D'Souza DH. 2013. Grape seed extract for foodborne virus reduction on produce. Food Microbiol 34:1–6. 10.1016/j.fm.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farkas T, Sestak K, Wei C, Jiang X. 2008. Characterization of a rhesus monkey calicivirus representing a new genus of Caliciviridae. J Virol 82:5408–5416. 10.1128/JVI.00070-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang D, Huang P, Zou L, Lowary TL, Tan M, Jiang X. 2015. Tulane virus recognizes the A Type 3 and B histo-blood group antigens. J Virol 89:1419–1427. 10.1128/JVI.02595-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tan M, Wei C, Huang P, Fan Q, Quigley C, Xia M, Fang H, Zhang X, Zhong W, Klassen JS, Jiang X. 2015. Tulane virus recognizes sialic acids as cellular receptors. Sci Rep 5–:11784. 10.1038/srep11784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bridges DF, Breard A, Lacombe A, Valentine DC, Tadepalli S, Wu VCH. 2017. Inhibition of Tulane virus replication via exposure to lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) fractional components. JBR 7:281–289. 10.3233/JBR-170164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Huang R, Chen H. 2017. Evaluation of assays to quantify infectious human norovirus for heat and high-pressure inactivation studies using Tulane virus. Food Environ Virol 9:314–325. 10.1007/s12560-017-9288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ailavadi S, Davidson PM, Morgan MT, D'Souza DH. 2019. Thermal inactivation kinetics of Tulane virus in cell-culture medium and spinach. J Food Sci 84:557–563. 10.1111/1750-3841.14461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Araud E, Fuzawa M, Shisler JL, Li J, Nguyen TH. 2020. UV inactivation of rotavirus and Tulane virus targets different components of the virions. Appl Environ Microbiol 86:e02436-19. 10.1128/AEM.02436-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho YS, McKay G. 1999. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem 34:451–465. 10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho YS, Ng JCY, McKay G. 2001. Removal of lead(II) from effluents by sorption on peat using second-order kinetics. Sep Sci Technol 36:241–261. 10.1081/SS-100001077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho YS, Ofomaja AE. 2006. Pseudo-second-order model for lead ion sorption from aqueous solutions onto palm kernel fiber. J Hazard Mater 129:137–142. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu G, Zhang D, Guo F, Tan M, Jiang X, Jiang W. 2013. Cryo-EM structure of a novel calicivirus. PLoS One 8:e59817. 10.1371/journal.pone.0059817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pianet I, André Y, Ducasse M-A, Tarascou I, Lartigue J-C, Pinaud N, Fouquet E, Dufourc EJ, Laguerre M. 2008. Modeling procyanidin self-association processes and understanding their micellar organization: a study by diffusion nmr and molecular mechanics. Langmuir 24:11027–11035. 10.1021/la8015904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam B, Sharma C, Adem A, Aburawi E, Ojha S. 2015. Insight into the mechanism of polyphenols on the activity of HMGR by molecular docking. Drug Des Devel Ther 9:4943–4951. 10.2147/DDDT.S86705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srinivasan E, Rajasekaran R. 2016. Computational investigation of curcumin, a natural polyphenol that inhibits the destabilization and the aggregation of human SOD1 mutant (Ala4Val). RSC Adv 6:102744–102753. 10.1039/C6RA21927F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chedea VS, Echim C, Braicu C, Andjelkovic M, Verhe R, Socaciu C. 2011. Composition in polyphenols and stability of the aqueous grape seed extract from the romanian variety “merlot recas. J Food Biochem 35:92–108. 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2010.00368.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodríguez Montealegre R, Romero Peces R, Chacón Vozmediano JL, Martínez Gascueña J, García Romero E. 2006. Phenolic compounds in skins and seeds of ten grape Vitis vinifera varieties grown in a warm climate. J Food Compos Anal 19:687–693. 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pierce BG, Hourai Y, Weng Z. 2011. Accelerating protein docking in ZDOCK using an advanced 3D convolution library. PLoS One 6:e24657. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chowdhury R, Allan MF, Maranas CD. 2018. OptMAVEn-2.0: de novo design of variable antibody regions against targeted antigen epitopes. Antibodies 7:23. 10.3390/antib7030023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campillay-Véliz CP, Carvajal JJ, Avellaneda AM, Escobar D, Covián C, Kalergis AM, Lay MK. 2020. Human norovirus proteins: implications in the replicative cycle, pathogenesis, and the host immune response. Front Immunol 11:961. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cosconati S, Forli S, Perryman AL, Harris R, Goodsell DS, Olson AJ. 2010. Virtual screening with AutoDock: theory and practice. Expert Opin Drug Discov 5:597–607. 10.1517/17460441.2010.484460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaudhury S, Lyskov S, Gray JJ. 2010. PyRosetta: A script-based interface for implementing molecular modeling algorithms using Rosetta. Bioinformatics Oxford Academic 26:689–691. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soares S, Mateus N, De Freitas V. 2007. Interaction of different polyphenols with Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) and Human Salivary α-Amylase (HSA) by fluorescence quenching. J Agric Food Chem 55:6726–6735. 10.1021/jf070905x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson M. 2012. Fetal bovine serum. Mater Methods 2:117. 10.13070/mm.en.2.117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bultmann H, Busse JS, Brandt CR. 2001. Modified FGF4 signal peptide inhibits entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. J Virol 75:2634–2645. 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2634-2645.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lodder WJ, De Roda Husman AM. 2005. Presence of noroviruses and other enteric viruses in sewage and surface waters in the Netherlands. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1453–1461. 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1453-1461.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rutjes SA, Lodder WJ, Van Leeuwen AD, De Roda Husman AM. 2009. Detection of infectious rotavirus in naturally contaminated source waters for drinking water production. J Appl Microbiol 107:97–105. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cromeans T, Park GW, Costantini V, Lee D, Wang Q, Farkas T, Lee A, Vinjé J. 2014. Comprehensive comparison of cultivable norovirus surrogates in response to different inactivation and disinfection treatments. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:5743–5751. 10.1128/AEM.01532-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shanmuganayagam D, Beahm MR, Osman HE, Krueger CG, Reed JD, Folts JD. 2002. Grape seed and grape skin extracts elicit a greater antiplatelet effect when used in combination than when used individually in dogs and humans. J Nutr 132:3592–3598. 10.1093/jn/132.12.3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oh C, Sun PP, Araud E, Nguyen TH. 2020. Mechanism and efficacy of virus inactivation by a microplasma UV lamp generating monochromatic UV irradiation at 222 nm. Water Res 186. 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunkin N, Weng S, Schwab KJ, McQuarrie J, Bell K, Jacangelo JG. 2017. Comparative inactivation of murine norovirus and ms2 bacteriophage by peracetic acid and monochloramine in municipal secondary wastewater effluent. Environ Sci Technol 51:2972–2981. 10.1021/acs.est.6b05529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oguma K, Kita R, Sakai H, Murakami M, Takizawa S. 2013. Application of UV light emitting diodes to batch and flow-through water disinfection systems. Desalination 328:24–30. 10.1016/j.desal.2013.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Araud E, DiCaprio E, Ma Y, Lou F, Gao Y, Kingsley D, Hughes JH, Li J. 2016. Thermal inactivation of enteric viruses and bioaccumulation of enteric foodborne viruses in live oysters (Crassostrea virginica). Appl Environ Microbiol 82:2086–2099. 10.1128/AEM.03573-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dong S, Li J, Kim MH, Park SJ, Eden JG, Guest JS, Nguyen TH. 2017. Human health trade-offs in the disinfection of wastewater for landscape irrigation: microplasma ozonation: vs. chlorination. Environ Sci: Water Res Technol 3:106–118. 10.1039/C6EW00235H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bustin SA, Benes V, Garson JA, Hellemans J, Huggett J, Kubista M, Mueller R, Nolan T, Pfaffl MW, Shipley GL, Vandesompele J, Wittwer CT. 2009. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin Chem 55:611–622. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gerba CP, Betancourt WQ. 2017. Viral aggregation: impact on virus behavior in the environment. Environ Sci Technol 51:7318–7325. 10.1021/acs.est.6b05835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mattle MJ, Kohn T. 2012. Inactivation and tailing during UV254 disinfection of viruses: Contributions of viral aggregation, light shielding within viral aggregates, and recombination. Environ Sci Technol 46:10022–10030. 10.1021/es302058v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Floyd R, Sharp DG. 1977. Aggregation of poliovirus and reovirus by dilution in water. Appl Environ Microbiol 33:159–167. 10.1128/aem.33.1.159-167.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kahler AM, Cromeans TL, Metcalfe MG, Humphrey CD, Hill VR. 2016. Aggregation of Adenovirus 2 in Source Water and Impacts on Disinfection by Chlorine. Food Environ Virol 8:148–155. 10.1007/s12560-016-9232-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang J, Anishchenko I, Park H, Peng Z, Ovchinnikov S, Baker D. 2020. Improved protein structure prediction using predicted interresidue orientations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 117:1496–1503. 10.1073/pnas.1914677117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1 to S3, Text S1, and Fig. S1 to S7. Download aem.02247-21-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.9 MB (1.9MB, pdf)

REMARK predicted structure (Ratul Chowdhury). Download aem.02247-21-s0002.txt, TXT file, 0.91 MB (940KB, txt)