Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Funding source

None declared.

Dear Editor,

We are living an ongoing global COVID‐19 pandemic which is associated with a considerable number of fatal cases worldwide. 1 Vaccines are the promising solution to minimize the problem amongst cancer patients; however, there are limitations to be considered such as the efficacy of COVID‐19 vaccines for immunocompromised individuals and possible interactions between the vaccine and cancer. 2 , 3 , 4

On the latest issue of JEADV, Damiani et al. 5 reported exacerbation of immunobullous diseases post COVID‐19 vaccination.

We present two CTCL cases which were in remission for many years and the immunization with viral vector COVID‐19 vaccine (Vaxzevria, Oxford/AstraZeneca, Cambridge, England) induced them to reappear.

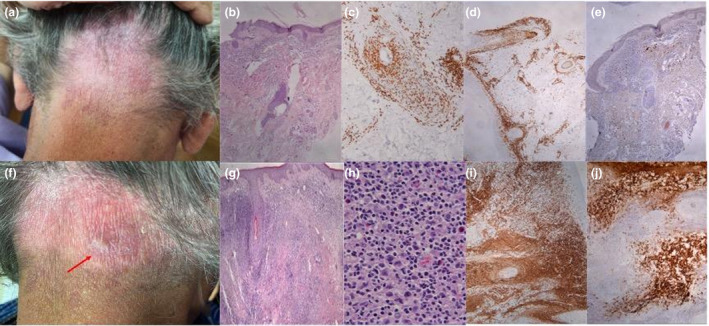

The first case is a 60‐year‐old male diagnosed with folliculotropic mucosis fungoides (MF) tumour, stage T1a/ΙΑ. Clinically, he presented with areas of alopecia areata such as rash (i.e. patches with hair loss on the face, arms and pubic area with no epidermal involvement) and minor patches in the same anatomic locations. The last 2 years, the disease was stage T1aN0M0 with only one stable patch on the occipital area (Fig. 1a–e); 4 weeks after the first dose of the vaccine, a minor lichenoid induration on the periphery of the patch was observed. A week after the second dose, small nodules were detected on the same location (Fig. 1f). An incisional biopsy was performed and the diagnosis of CD30+ large cell transformation (LCT) tumour stage MF (Fig. 1g–j) was set by immunohistochemistry and PCR analysis.

Figure 1.

Clinical presentation and histology before (a–e) and after (f–j) the vaccine. (a) Purple patch on the occipital area, (b) H&E ×20: Lymphoid infiltration of the dermis with prominent folliculotropism, (c) CD3 ×40: CD3 expression, (d) CD4 ×20: CD4 expression, (e) CD30 ×20: Sparse CD30 positivity, (f) Lichenoid induration and small nodules on the periphery of the patch, (g) H&E ×20: dense, diffuse, full thickness lymphoid infiltration of the dermis, (h) H&E ×400: increased numbers of large neoplastic T lymphocytes among the lymphocytic population, (i) CD3 X 20: CD3 expression, (j) CD30 ×40: extensive CD30 positivity mainly in the large anaplastic T lymphocytes (transformation to peripheral CD30+ T‐cell lymphoma).

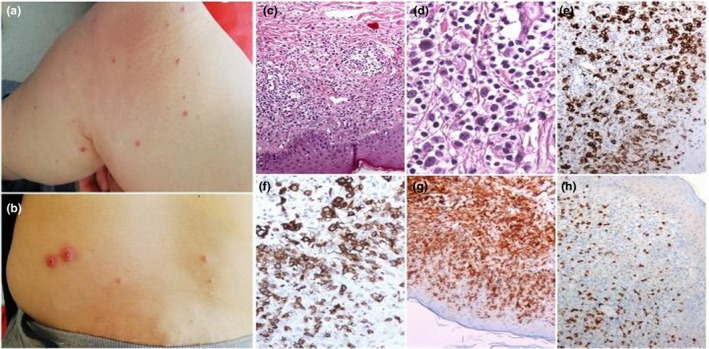

The second case is a 73‐year‐old female, with a 10‐year history of early‐stage MF (stage T1a/IA) and lymphomatoid papulosis type A (LyP). Both diagnoses were immunocytochemically and molecularly confirmed. She was treated successfully with PUVA and she was in remission the last 7 years. Ten days after the first dose of the vaccine, she developed a rash on areas where LyP was previously evident (Fig. 2a). The histology confirmed the diagnosis of LyP type‐A (Fig. 2c–h).

Figure 2.

Clinical presentation and histology after the vaccine. (a) Erythematous papules on the dorsal aspect of the thigh, (b) erythematous papules and scaly plaques on the abdominal area, (c) H&E ×100, (d) diffuse H&E ×200: polymorphic infiltration of the reticular dermis by lymphocytes of various sizes (small to large anaplastic), (e) CD30 ×100, (f) CD30 ×200: CD30 expression by the majority of the lymphocytic population, (g) CD4 ×100: Predominantly CD4 expression, (h) CD8 ×100: CD8 expression.

The question which is raised in these cases is whether and via which pathway the vaccine has caused the MF CD30+ LCT and the reappearance of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoprolipherative disorder.

According to the literature, the education of CD4+ T, CD8+ T and B cells against SARS‐CoV‐2 S protein appears to be the most feasible way for COVID‐19 vaccine production. Both cancers and coronavirus provide a persistent and chronic antigenic load, amongst which PD‐1, resulting in T‐cell exhaustion. Therefore, it is important to assure the vaccination would not cause a further T‐cell exhaustion state which may have already been induced by tumour cells. 6 , 7 , 8

CD30 is expressed on a small subset of activated T and B lymphocytes and a variety of lymphoid neoplasms. Studies showed that CD30 expression on lymphocytes could be induced by in vitro antigenic stimulation by mitogens or viruses such as HSV. CD30 expression appears higher in CD4+ and CD8+ cells producing a Th2‐type cytokine response. 6 Recently, Brumfiel et al., 7 reported a case of recurrence of cutaneous CD30 positive lymphoma following mRNA vaccine (Pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccine, New York, NY, USA). In our case, it was given a viral vector vaccine which does not include live viruses, however, contains a part of the coronavirus stuck to adenovirus, which triggers an immune response. We speculate that the recurrence of the disease in our patients as well as Brumfiel's case was possibly caused by the activation of CD30 via the above pathway i.e. overproduction and exhaustion of CD4+ and CD8+ cells which expressed CD30 after being triggered by the adenovirus. However, this could also be a coincidental finding, unrelated to the vaccine since MF and especially the LyP are known for a waxing and waning course of the disease.

To our knowledge, reappearance of a pre‐existing neoplastic condition or lymphoproliferative disease post COVID‐19 vaccination is extremely uncommon. Currently, there is limited evidence in regard to the safety and efficacy of vaccines in patients with altered immunity. Further studies are needed for this target group of patients.

Acknowledgement

The patients in this manuscript have given written informed consent to the publication of their case details.

References

- 1. McPeake J, Pattison N. COVID‐19: Moving beyond the pandemic. J Adv Nurs 2020; 76: 2447–2449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R et al. Cancer patients in SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21: 335–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/jdv.17472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moris D, Tsilimigras DI, Schizasc D. Cancer and COVID‐19. Lancet 2020; 396: 1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Han HJ, Nwagwu C, Anyim O, Ekweremadu C, Kime S. COVID‐19 and cancer: From basic mechanisms to vaccine development using nanotechnology. Int Immunopharmacol 2021; 90: 107247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Damiani G, Pacifico A, Pelloni F, Iorizzo M. The first dose of COVID‐19 vaccine may trigger pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid flares: is the second dose therefore contraindicated? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021; 35. 10.1111/jdv.17472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. van der Weyden CA, Pileri SA, Feldman AL, Whisstock J, Prince HM. Understanding CD30 biology and therapeutic targeting: a historical perspective providing insight into future directions. Blood Cancer J 2017; 7: e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brumfiel CM, Patel MH, Puri P et al. Recurrence of primary cutaneous CD30 positive lymphoproliferative disorder following COVID‐19 vaccination. Leuk Lymphoma 2021. 10.1080/10428194.2021.1924371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Soleimanpour S, Yaghoubi A. COVID‐19 vaccine: where are we now and where should we go? Expert Rev Vaccines 2021; 20: 23–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]