Abstract

Purpose

How completely do hospital discharge diagnoses identify cases of myopericarditis after an mRNA vaccine?

Methods

We assembled a cohort 12–39 year‐old patients, insured by Kaiser Permanente Northwest, who received at least one dose of an mRNA vaccine (Pfizer‐BioNTech or Moderna) between December 2020 and October 2021. We followed them for up to 30 days after their second dose of an mRNA vaccine to identify encounters for myocarditis, pericarditis or myopericarditis. We compared two identification methods: A method that searched all encounter diagnoses using a brief text description (e.g., ICD‐10‐CM code I40.9 is defined as ‘acute myocarditis, unspecified’). We searched the text description of all inpatient or outpatient encounter diagnoses (in any position) for “myocarditis” or “pericarditis.” The other method was developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD), which searched for emergency department visits or hospitalizations with a select set of discharge ICD‐10‐CM diagnosis codes. For both methods, two physicians independently reviewed the identified patient records and classified them as confirmed, probable or not cases using the CDC's case definition.

Results

The encounter methodology identified 14 distinct patients who met the confirmed or probable CDC case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis with an onset within 21 days of receipt of COVID‐19 vaccination. When we extended the search for relevant diagnoses to 30 days since vaccination, we identified two additional patients (for a total of 16 patients) who met the case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis, but those patients had been misdiagnosed at the time of their original presentation. Three of these patients had an ICD‐10‐CM code of I51.4 “Myocarditis, Unspecified;” that code was omitted by the VSD algorithm (in the late fall of 2021). The VSD methodology identified 11 patients who met the CDC case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis. Seven (64%) of the 11 patients had initial care for myopericarditis outside of a KPNW facility and their diagnosis could not be ascertained by the VSD methodology until claims were submitted (median delay of 33 days; range of 12–195 days). Among those who received a second dose of vaccine (n = 146 785), we estimated a risk as 95.4 cases of myopericarditis per million second doses administered (95% CI, 52.1–160.0).

Conclusion

We identified additional valid cases of myopericarditis following an mRNA vaccination that would be missed by the VSD's search algorithm, which depends on select hospital discharge diagnosis codes. The true incidence of myopericarditis is markedly higher than the incidence reported to US advisory committees in the fall of 2021. The VSD should validate its search algorithm to improve its sensitivity for myopericarditis.

Keywords: COVID‐19 vaccination, hospital claims, ICD‐10 code, incidence of myopericarditis, myopericarditis, Vaccine Safety Datalink

Key Points

We identified a higher estimate of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine by searching encounter text description compared with the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) methodology.

An incomplete list of ICD‐10‐CM codes and delays in hospital claims data were responsible for the difference.

We estimated a risk of 95.4 cases of myopericarditis per million second doses administered in patients age 12–39 that is higher than the incidence reported to US advisory committees in the fall of 2021.

We encourage other VSD sites to validate the case ascertainment.

Plain Language Summary

This report identifies that our encounter methodology identified approximately twice as many cases of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination than the CDC's Vaccine Safety Datalink. Omissions in ICD‐10‐CM codes and claims delays were the primary reasons the VSD's search algorithm missed these cases.

1. PURPOSE

Post‐marketing vaccine safety in the US is monitored through the complimentary Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) and the Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD). VSD has conducted weekly vaccine surveillance known as rapid cycle analysis since the first COVID‐19 vaccine was administered in December 2020 to identify rare or serious vaccine related outcomes not identified in clinical trials. 1 This surveillance system looks for serious outcomes associated with 23 pre‐specified signals, however the sensitivity of the risk estimates may be limited by only including specific ICD‐10‐CM codes, and by delays in claims processing when care occurs outside the integrated health system and exclusion of outpatient visits.

Myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination is well reported, 2 , 3 , 4 and the FDA and CDC use VSD analyses of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination to implement decisions about vaccine policy.

Here we compare the risk of myopericarditis using health record encounter text analysis compared with the VSD rapid cycle analysis methodology from a single integrated health system, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a VSD participant. 1 KPNW represents approximately 7% of the entire VSD population. The purpose of this study was to compare how completely the different methodologies identify post‐vaccination myopericarditis.

2. METHODS

We assembled a cohort of 153 438 adolescents and adults (12–39 years old) who were covered by KPNW and were vaccinated with at least one dose of an mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine between December 18, 2020 and October 16, 2021. The cohort was followed for up to 30 days after their second dose of an mRNA vaccine to identify encounters for myocarditis, pericarditis or myopericarditis. Encounters included telehealth visits, outpatient visits, including urgent care visits, as well as emergency department visits or hospitalizations. KP's institutional review board (IRB) approved the study.

KPNW's electronic health record (EHR) is a version of Epic's EHR system and captures all encounter diagnoses assigned within KP's integrated delivery system and affiliated community. The National Center for Health Statistics developed a brief text description or label to define their clinical modification of ICD‐10‐CM diagnosis codes. For example, I40.9 is defined as, “acute myocarditis, unspecified.” We searched the text description of all the KPNW encounter diagnoses (in any position) that occurred between December 18, 2020 and October 16, 2021 in both the outpatient and inpatient settings to identify encounters related to “myocarditis” or “pericarditis.” We excluded anyone with a documented diagnosis of myocarditis or pericarditis before their first mRNA vaccination. We excluded patients with a diagnosis of COVID‐19 infection prior to the diagnosis of myopericarditis. Two physicians independently reviewed the identified patients' full medical records and applied the CDC myocarditis and pericarditis surveillance case definition to classify records as confirmed, probable or not cases based on the prior published definition. 5

To reproduce the VSD methodology 2 we restricted our search to select ICD‐10‐CM discharge codes from emergency department visits and hospitalizations, including hospitals owned by KPNW and hospitals unaffiliated with KPNW, which submit insurance claims to KPNW. Each diagnosis associated with an ICD‐10‐CM code of B33.22, B33.23, I30,* or I40* was then flagged as meeting the criteria of being identified by the VSD. As above, two physicians independently reviewed the patient records to classify as confirmed, probable or not cases based on the case definition. 5

We calculated the risk per million second doses of vaccine. We stratified the risk by age bands to understand how the risk of myocarditis or pericarditis depended on age. We calculated exact 95% confidence intervals using Stata 17 and the default Clopper‐Pearson binomial method. 6

3. RESULTS

The encounter text description methodology identified 14 distinct patients ages 12–39 years old who met the confirmed or probable CDC case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis within 21 days of receipt of COVID‐19 vaccination. Three of these patients had an ICD‐10‐CM code of I51.4 myocarditis, Unspecified which was unique to the encounter text description methodology (i.e., omitted from the VSD algorithm). When we extended the search for relevant diagnoses to 30 days since vaccination, we identified two additional patients (Patient #15 and #16) who met the case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis, but those patients had been misdiagnosed at the time of their original presentation. The original symptomatic presentation was still within 21 days since vaccination, but the condition was misdiagnosed and subsequently recognized during an outpatient follow up visit. We included all 16 patients in our data analysis.

Using the VSD methodology, we identified 11 patients ages 12–39 years old who met the CDC case definition for acute myocarditis or pericarditis within 21 days of receipt of COVID‐19 vaccination. Seven (64%) of the 11 patients had initial care for myopericarditis outside of a KPNW facility and their diagnosis could not be ascertained by the VSD methodology until claims were submitted. Four of the 11 cases identified by the VSD had claims data submitted after 30 days, with an average claims delay of 64 days and a median delay of 33 days (range 12–195 days). Claims data for these events were submitted from patient encounters at community hospitals that are not owned by Kaiser Permanente Northwest but provide care for our patients. These emergency department visits and hospitalizations outside of KP facilities are reimbursed when hospitals submit an insurance claim for the care that was provided and allow for physician adjudication of the cases (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Summary of myopericarditis cases identified by encounter text description and Vaccine Safety Datalink (VSD) methodology

| Patient | Age | Sex | Vaccine | Dose | Days to chest pain onset | EKG | Trop peak mcg/L | Evaluation of CAD | LVEF on echo, % or cardiac MRI | LOS, d | VSD method | Reason missed by VSD | Days to claim filed for VSD a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | Sinus arrythmia | 4.08 | Not done | 57%‐MRI | 1 | No | I51.4 not queried | |

| 2 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 4 | Sinus | 2.9 | Not done | 70% | 2 | No | I51.4 not queried | |

| 3 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 1 | Sinus Tach | 11.1 | Not done | 40% | 2 | No | I51.4 not queried | |

| 4 | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 2 | ST elevation | 4.02 | Not done | 62%‐MRI | 2 | Yes | Delay in claim | 33 |

| 5 | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | ST elevation | 12.4 | Not done | 61%‐MRI | 5 | Yes | Delay in claim | 74 |

| 6 c | 30–39 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 15 | ST elevation | ≤0.03 | Not done | Not done | ED | Yes | Delay in claim | 82 |

| 7 c | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 1 | 7 | ST abnormality | 0.5 | Normal angio | 22% | 43 | Yes | Delay in claim | 195 |

| 8 | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | Sinus | 13.3 | Not done | Normal | 3 | Yes | Internal b | |

| 9 | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | ST elevation | 66.13 | Not done | 27%‐MRI | 4 | Yes | 29 | |

| 10 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | Sinus | 0.38‐Trop T | Not done | 55%–60% | ED | Yes | 22 | |

| 11 | 18–24 | F | Moderna | 2 | 4 | ST elevation, sinus tach | 15.9 | Not done | 60% | 1 | Yes | Internal b | |

| 12 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | Sinus | 5.19 | Not done | 68%‐MRI | 1 | Yes | Internal b | |

| 13 | 18–24 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 3 | ST elevation | 4.9 | Not done | 50% | 1 | Yes | 12 | |

| 14 | 18–24 | M | Moderna | 2 | 3 | ST elevation, lateral | 9.62 | Not done | 48%–55% | 1 | Yes | Internal b | |

| 15 | 12–17 | M | Pfizer | 2 | 4 | Sinus | 0.04 | Not done | Normal | ED | No | Misdiagnosed during first 21 days | |

| 16 c | 30–39 | F | Pfizer | 1 | 1 | Antero‐lateral ischemia | ≤0.03 | Normal angio | 60%–65% | OP | No | Misdiagnosed during first 21 days |

Note: Normal troponin range: ≤0.03 mcg/L.

Abbreviations: ED: emergency department; LVEF: left‐ventricular end‐systolic function; OP: outpatient.

Days to claim filed measures the number of days between the first clinical encounter for myopericarditis and the outside hospital or clinic filing an insurance claim with KPNW for cases detected by VSD methodology. Real‐time surveillance would miss events that were only recognized through delayed insurance claims. For example, patient 7 would not have been identified by an algorithm based on insurance claims for more than 6 months after the onset of myopericarditis (195 days). In contrast, when the myopericarditis was diagnosed at a KPNW‐owned hospital or clinic there was no need for an insurance claim to be submitted; those are marked “internal” for encounters within the KPNW integrated delivery system.

Internal: Internal hospital encounter, claims data not used to identify case for the VSD methodology.

Cases that met case definition but were atypical from general pattern.

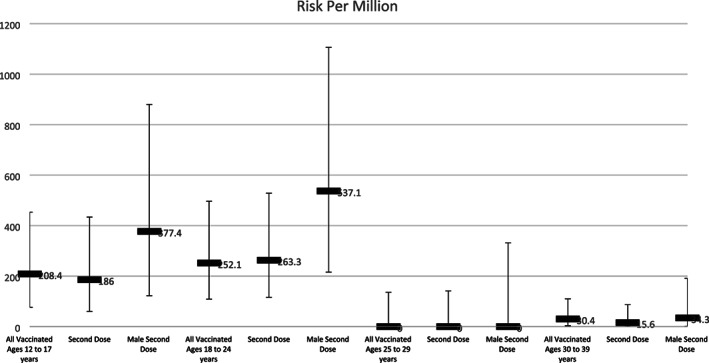

In our patients ages 12–39 years old who received a second dose of vaccine (n = 146 785), we estimated a risk of 95.4 cases of myopericarditis per million second doses administered (95% CI, 52.1 to 160.0). In males who received a second dose (n = 66 533) we estimated a risk of 195.4 cases of myopericarditis per million second doses (95% CI, 104.0 to 334.1) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The risk of myopericarditis per million doses of COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine by age, sex, and dose number

4. CONCLUSION

We identified a higher estimate of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine by searching encounter text description of an integrated health system compared with the VSD methodology. The VSD specifically excluded ICD‐10‐CM code I51.4, (myocarditis, unspecified) resulting in missed diagnoses that met the case definition. Additionally, some of the VSD sites rely on claims data from community hospitals that are not owned by the health systems to identify cases. Although their methodology may eventually identify these cases if the analysis was conducted several months after all the events occurred, the lag in claims submission and payment may result in inaccurate case estimates.

Finally, by extending our search for a relevant diagnosis to 30 days since vaccination, we were able to capture additional events that met the case definition but were not coded in the health record by day 21. For example, patient #15 had a hospital discharge code of Chest Pain (ICD‐10‐CM code R07.9), that occurred 4 days after vaccination, however when he had follow‐up in the pediatric cardiology clinic the appropriate diagnosis code of Idiopathic Myocarditis (ICD‐10‐CM code I40.1) was documented. This outpatient pediatric cardiology appointment occurred at day 25 after his initial presentation. A similar scenario occurred with patient #16 whose initial encounter was diagnosed as Chest Pain (ICD‐10‐CM code R07.9) which occurred 1 day after vaccination. She had cardiology evaluation >21 days after the initial presentation, and received the more specific code of Pericarditis, Unspecified (ICD‐10‐CM I31.9). It is unclear why a 21‐day cut‐off was defined by the VSD and by expanding our search for a relevant diagnosis to 30 days since vaccination, we were able to identify additional events. However, the number of chart reviews to adjudicate the additional cases identified between days 22 through 30 may not merit the associated work burden for this incremental improvement in case ascertainment.

Our estimate of the incidence of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccine is similar in magnitude to that reported from studies from Israel and Hong Kong 7 , 8 , 9 but higher than that reported in the US studies and at Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) and Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meetings during the fall of 2021. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 Complete case estimates are essential when modeling risk and benefit for wide‐scale vaccine implementation and booster doses in younger age groups.

The encounter text description methodology identified approximately twice as many cases of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. The VSD is a multi‐site consortium with several sites relying on outside claims data to identify cases, potentially resulting in prolonged data lags for accurate ascertainment of events. We would encourage other VSD sites to validate the case ascertainment of the VSD methodology. Future modeling and public policy decisions on vaccine safety should consider the limitations of VSD derived estimates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Sharff KA, Dancoes DM, Longueil JL, Johnson ES, Lewis PF. Risk of myopericarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination in a large integrated health system: A comparison of completeness and timeliness of two methods. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2022;31(8):921‐925. doi: 10.1002/pds.5439

REFERENCES

- 1. Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390‐1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marshall M, Ferguson ID, Lewis P, et al. Symptomatic acute myocarditis in 7 adolescents after Pfizer‐BioNTech COVID‐19 vaccination. Pediatrics. 2021;148(3):e2021052478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kim HW, Jenista ER, Wendell DC, et al. Patients with acute myocarditis following mRNA COVID‐19 vaccination. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1196‐1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Montgomery J, Ryan M, Engler R, et al. Myocarditis following immunization with mRNA COVID‐19 vaccines in members of the US military. JAMA Cardiol. 2021;6(10):1202‐1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gargano JW, Wallace M, Hadler SC, et al. Use of mRNA COVID‐19 vaccine after reports of myocarditis among vaccine recipients: update from the advisory committee on immunization practices ‐ United States, June 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(27):977‐982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clopper CJ, Pearson ES. The use of confidence or fiducial limits illustrated in the case of the binomial. Biometrika. 1934;26:404‐413. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against Covid‐19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2140‐2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Witberg G, Barda N, Hoss S, et al. Myocarditis after Covid‐19 vaccination in a large health care organization. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2132‐2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chua GT, Kwan MYW, Chui CSL, et al. Epidemiology of acute myocarditis/pericarditis in Hong Kong adolescents following Comirnaty vaccination. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;ciab989. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oster ME, Shay DK, Su JR, et al. Myocarditis cases reported after mRNA‐based COVID‐19 vaccination in the US from December 2020 to august 2021. JAMA. 2022;327(4):331‐340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Simone A, Herald J, Chen A, et al. Acute myocarditis following COVID‐19 mRNA vaccination in adults aged 18 years or older. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(12):1668‐1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Oster M, Oliver S, Proceedings of the advisory committee on immunization practices 11/2/2021, ACIP November 2‐3, 2021 Presentation Slides | Immunization Practices | CDC; 2021.

- 13. Oster M, Proceedings of the Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, 10/26/21. Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee October 26, Meeting Announcement ‐ 10/26/2021–10/26/2021 | FDA; 2021.