Abstract

Background:

Cost is a major consideration in the uptake and continued use of diabetes technology. With increasing use of automated insulin delivery systems, it is important to understand the specific cost-related barriers to technology adoption. In this qualitative analysis, we were interested in understanding and examining the decision-making process around cost and diabetes technology use.

Materials and Methods:

Four raters coded transcripts of four stakeholder groups using inductive coding for each stakeholder group to establish relevant themes/nodes. We applied the Social Ecological Model in the interpretation of five thematic levels of cost.

Results:

We identified five thematic levels of cost: policy, organizational, insurance, interpersonal and individual. Equitable diabetes technology access was an important policy-level theme. The insurance-level theme had multiple subthemes which predominantly carried a negative valence. Participants also emphasized the psychosocial burden of cost specifically identifying diabetes costs to their families, the guilt of diabetes related costs, and frustration in the time and involvement required to ensure insurance coverage.

Conclusion:

We found broad consensus in how cost is experienced by stakeholder groups. Cost considerations for diabetes technology uptake extended beyond finances to include time, cost to society, morality and interpersonal relationships. Cost also reflected an important moral principle tied to the shared desire for equitable access to diabetes technology. Knowledge of these considerations can help clinicians and researchers promote equitable device uptake while anticipating barriers for all persons living with type 1 diabetes and their families.

Keywords: qualitative research, automated insulin delivery, diabetes technology, psychosocial barriers

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Advances in diabetes technology in the last decade have resulted in a marked rise in diabetes technology use and are associated with improvements in type 1 diabetes outcomes.1,2 In particular, continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and hybrid closed-loop systems have emerged as promising new technology.3-5 CGM use alone, irrespective of type of insulin delivery, is associated with an improvement in HbA1c.6 Hybrid closed-loop systems have consistently demonstrated improvements in HbA1c and time in range while decreasing rates of hypoglycaemia, severe hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis.3-5 Additionally, hybrid closed-loop systems have shown improvements in diabetes distress, quality of life and health-related quality of life.7

With increasing government approval of algorithms that allow for automated insulin delivery as well as the increased adoption of do-it-yourself hybrid closed-loop algorithms, it is important to understand barriers in adoption of these technologies in order to facilitate equitable uptake across all persons with type 1 diabetes. While diabetes technology uptake has increased over the last decade, population and registry data suggest that there is a differential uptake in youth from lower socio-economic status families.8,9 Taken with the fact that the most commonly cited barrier to diabetes technology use is cost,10,11 financial considerations may play a role in this differential uptake.11-13

Monetary and non-monetary costs of diabetes technology have been implicated in glycaemic control and adoption of technology. Monetary cost, such as out of pocket costs to secure diabetes technology coverage, may be a barrier to diabetes technology adoption. Non-monetary costs, such as travel to collect prescriptions and time spent coordinating shipment of technology, are also considered barriers to diabetes technology adoption. Cost may affect people across and within countries differently as is seen in the United States with variability in public payer coverage by state and county.13,14 Similarly, in the United Kingdom, despite payers such as the National Health Service, there is a tenfold variation in access to insulin pump therapy.15 In addition, a study evaluating insulin pump uptake in Ireland demonstrated that reimbursement alone as a cost consideration does not fully account for uptake of insulin pumps.11

Qualitative studies are foundational in understanding the lived experience of type 1 diabetes as well as factors surrounding diabetes technology uptake and use.10,16 These evaluations are particularly important when aiming to improve diabetes technology uptake as clinicians often misidentify or over identify barriers to diabetes technology use, which can lead to inadvertent gatekeeping and/or irrelevant solutions that are out of touch with the person's actual barriers.17 The INSPIRE study was a rigorous mixed-methods evaluation, including extensive qualitative investigation of the psychosocial factors associated with automated insulin delivery systems among persons living with type 1 diabetes and their families (n = 284) in the United States and the United Kingdom.10 Major themes critical for automated insulin delivery uptake included trust and control of the system, features of the systems and barriers to adoption. In addition to these critical considerations, financial aspects of automated insulin delivery systems emerged as a major barrier in the anticipated adoption of these systems. Therefore, the goal of this study is to analyse the qualitative data to further delineate the nuances of cost as a barrier in all of its forms as described by four stakeholder groups: youth, parents, adults and partners.

2 ∣. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Study overview

In the larger INSPIRE study, 134 qualitative sessions (58 sessions in the United Kingdom and 76 sessions in the United States) were carried out. The mean duration of the qualitative sessions was approximately 45 min with approximately 7 participants per session. The qualitative sessions included 284 total participants (51 youth, 65 parents, 113 adults and 55 partners) and 24 a priori codes were consolidated into 12 thematic clusters. This analysis was completed by nine raters in an iterative consensus-coding process. Participants in this study represent the broader population of people with type 1 diabetes and their views on cost. The qualitative sessions included those who utilized or accessed diabetes technology (such as CGM and insulin pumps) as well as those who utilized or accessed automated insulin delivery systems in particular. Inter-rater agreement of the themes presented was established both quantitatively and qualitatively in the INSPIRE study. A detailed description of study methodology and protocol for the larger INSPIRE study has been previously published.10

For this study, we analysed all sections that were previously coded and related to cost (‘General financial questions about automated insulin delivery systems’, ‘Automated insulin delivery systems’ out of pocket costs’ and ‘Insurance coverage and insurance questions regarding automated insulin delivery systems’). All data were organized by stakeholder groups: (1) youth: youth with type 1 diabetes, (2) parent: parents or identified caregivers of youth with type 1 diabetes, (3) adult: adults with type 1 diabetes and (4) partner: partners of adults with type 1 diabetes.

The dataset with the cost-related codes was anonymized, and therefore it was not possible to report demographic data. However, these data are presented for the broader INSPIRE study.10 The age range of the adults in the INSPIRE study was 18–77 years of age with a mean age of 39.5 years; 92% of the cohort self-identified as non-Hispanic White and 73% had a bachelor's degree or higher. The age range for youth was 9–21 years. Approximately 80% of the parents who responded were mothers and 90% of the parents identified their child's race as non-Hispanic White. As with the other stakeholder groups, partners were predominantly non-Hispanic White (95%).

2.2 ∣. Data analysis

For this sub-study analysis, four raters (AA, SCS, JJW and DN) formed the analysis team. Transcripts were uploaded and reviewed using QSR International's NVivo software version 12 for analysis. The transcripts possessing codes related to costs identified in earlier analyses were included and represented the four stakeholder groups (youth, parent, adult and partner). These transcripts were randomly assigned to two of four raters for analysis. The goal for this data analysis was to further elucidate the way that cost is characterized and impacts decision making across stakeholder groups. Therefore, for this in-depth analysis, coders began with open-coding, or inductive coding of the cost-coded transcripts to establish relevant themes/nodes. Five themes and 17 subthemes were identified in this first step. These codes were reconciled through consensus resulting in a pared down 13 coding themes related to costs and their impact on healthcare decisions. Further recoding identified a further three themes resulting in a final total of 16 thematic codes. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using Kappa coefficients supported by guidance from Landis and Koch.18

Empirical and interpretative meaning of themes were discussed by the analytical team until consensus was reached. In the final stage of analysis, the analysis team organized the newly identified themes in accordance with the Social Ecological Model19 as a theoretical structure to understand and interpret the cost-related themes identified. The themes raised by the stakeholder groups readily fell into the construct of the SEM. The SEM is a theoretical framework which accounts for interplay between individual, relationship, community and societal factors on behaviour. The SEM has been a useful model in understanding health and behavioural concepts in an individual's social environment with wide applications in the medical field.19-22

3 ∣. RESULTS

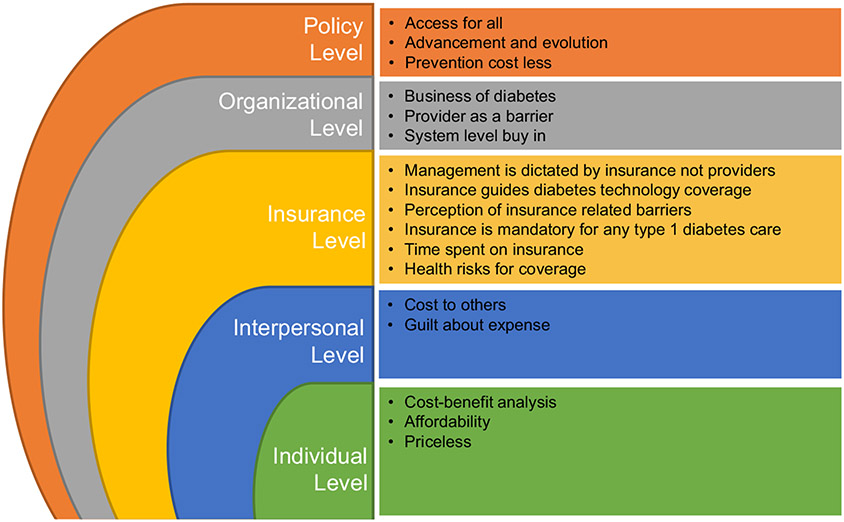

In this qualitative analysis of focus groups, cost is a major consideration for uptake and sustained use of automated insulin delivery systems. All stakeholder groups, including youth, described assessing cost considerations as it affects their day-to-day lives, their relationships with family, interactions with providers and insurance considerations. In addition, philosophical considerations of equity and access to diabetes technology for all persons with type 1 diabetes were frequently discussed. Themes, their descriptions and representative quotes are outlined in Table 1A-E. Theoretically grounded in the SEM as depicted in Figure 1, these themes were placed within the context of the complex interaction between individual, relationship, community and societal factors in the lives of people with type 1 diabetes. The following sections summarize the statements and ideas discussed by the study participants that reached thematic saturation.

TABLE 1A.

Policy level

| THEME | DESCRIPTION | QUOTE | STAKEHOLDER GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACCESS FOR ALL | The philosophical concept that all people should have access to diabetes technology regardless of ability of pay and across all insurances | I feel sorry for the people who—can’t do it—my age who can’t afford it. It’s the stupidest thing because having the MiniMed and not having—I mean the—I don’t understand the insurance the Medicare because the cost advantage of keeping us outside of emergency rooms, and keeping—for the stupid little device it’s just unbelievable to me. I got all the way to a—I’ve won the appeal three times and the insurance company is still fighting me. I’ve got the administrative judge to rule in my favor, and now the insurance company is completely inept. It’s something they call the Medicare something Board. They give me free Subway cards for $25, but they won’t pay for my sensors. I mean it’s just absurd. They’d rather—I mean it’s just absurd. It’s so stupid. I keep winning and they keep appealing. Eventually, January, I have to start paying myself for all this stuff. It’s their final appeal. Just dumb. | Adult |

| The biggest barrier would be finding access. You know I think that—I was listening to some of the comments this weekend about which device to use. Some people have a choice and some don’t really have a choice. We didn’t have choice—we didn’t have our own four choices from our insurance and then some there is a process that I am not aware—our doctor was just so great that we didn’t have problems; we just got it. She did whatever she was supposed to. I heard there had to be certain letters written and things like that, so—it needs to be more equitable first of all by way of financing accessibility should be a factor and then the big picture of no one should be without healthcare and whatever they need. Okay so that is the big picture, so this coming on the market, it needs to be accessible to everybody. That’s it. | Parent | ||

| ADVANCEMENT AND EVOLUTION | The notion that science, research and progress all contribute to better technology and care and this, in turn, promotes access and affordability | We need to see what the morbidity rates look like on this. What is the health cost over 20 years going to be with comparison to the benefits that are going to play out? That is how they look at it. And I am not faulting them for this. It is a business, right? But they don’t have Type 1 diabetics as owners or CEOs of those companies. If they did, those benefits would be different. | Adult |

| As far as the development into the technology of combining a CGM and a pump together, I believe that’s already been done, not in one device, just separately using a pump and then using a CGM. That’s already been done and people use that. I think it sounds expensive. It sounds very expensive for a technology that would be involved in both, and especially one that would be able to even have its own ability to correct itself, to change things, so a basic—I think if this were to be implemented in a future technology, something that has an algorithm for the way it reads data and applies a solution to it, and then, more algorithms that can correct that one. So, something of that much—essentially like the brain of a computer, that advanced of technology. I think that that sounds very expensive. It sounds very helpful. | Teen | ||

| PREVENTION COST LESS | Mention that if money was spent on prevention (i.e. diabetes technology), then it is overall less costly than end-stage ramifications | We just need to convince the government that in the long term there would be fewer people being really sick or in hospital. And I don’t think they’re going to believe us really. | Adult |

| I don’t think the NHS is very good at viewing things in the long term; so, I don’t know because I think the NHS looks at everything from the short term cost and gain and whatever. So, if it costs a lot of money I don’t know if they would view it favorably, but once a chance my case is put forward to it, and the evidence is there from what it can save in the long term and potentially even the short term in terms of shorter term issues, I don’t know. | Parent | ||

| Yeah, we had to apply for funding. So, we had to sort of give a reason why we were sort of more fit for funding than anyone else really. And we actually got a 100% funding, which was absolutely amazing. And I think they’d probably do it the same way, because there are certain people that their control is just so good that they just wouldn’t need the system. If they’re on a pump and whatever, and it comes to the point where you just simply don’t need it. For people like me where I’m really really active, obviously I have the hypos in the night which is something that I’m quite insecure about, I would hope that they wouldn’t turn a blind eye to that, and they would maybe give some funding towards it. And obviously I know diabetes costs the NHS so much money, so they could sort of cut the cost of diabetes then—I know that would make a massive difference as well. I think in the long term, it probably would be cheaper for the NHS. So not actually do it anyway, so yeah. | Teen |

TABLE 1E.

Individual level

| THEME | DESCRIPTION | QUOTE | STAKEHOLDER GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|

| COST–BENEFIT | Cost–Benefit is meant to capture the weighing costs of technology against the benefits of its use. | No, because I think my pump is more than adequate. But an AP system seems like it would just be that fine-tuning and that tiny bit of quality of life improvement, which would be lovely but not worth spending a lot on. So, I’m perfectly happy right now with the pump but if there was a—if it was given out for free, I would probably definitely go for it, but, no, pump is adequate enough, I mean not to desperately want to buy it. | Adult |

| I would be willing to, yes probably. I think if I really believed it could increase my overall health then I would give it a go. 50 pounds would be something that I would be easily manageable. 75 would push. I think more than 100 then I wouldn’t be willing to try because I wouldn’t have the funds to do so. Not on a regular basis. That’s why I want to past the year. | Adult | ||

| It depends on how the system works and if the system works. At the moment we pay for the Libre; we pay a hundred pound per month for the Libre for the sensor for her. We don’t necessarily always use the sensor on [Daughter] because we can’t use it instead of blood sugar testing, finger pricking, due to the fact that it's not accurate, but we’ll use it for trending. So it depends. I would pay anything if it helped [Daughter] in becoming much more independent and the system worked. | Parent | ||

| COST MATTERS | Cost Matters is a sub-consideration under this cost–benefits where regardless of the benefits, one must be prudent about the money spent and the thought that only so much should be spent on technology | I think that on one hand you want to live a better life in terms of your well-being so much at the end and health-wise. On the other hand you don’t want to sacrifice everything to do that. You know like personally I want an artificial pancreas and I am sure everyone else does here as well, but on the other hand I don’t want to be broke like I can’t go out with my mates, I can’t do anything because the reason why I am getting the pancreas in the first place is so that I can do that without worrying about my diabetes. I’d rather—I don’t want to stop worrying about my diabetes but then have to worry about money. On the same level it is like some people might not be able to afford it because it is really expensive but some people might find ways but on the other hand it would be unfair if people who were better off gain more out of it than people who aren’t. Just because you haven’t got a lot of money doesn’t mean you are not entitled to live a normal and healthy life. | Adult |

| I did investigate that and my insurance will only cover so much and that was a downside for me because they were expecting me to come out of pocket for so much more money outside of what they were going to pay. I just could not afford it at that time. | Parent | ||

| I think that price-wise, that would be quite difficult for us because it took us ages to be able to get some of the sensors. We paid for them quite a while before we managed to get funding. The company and NHS then funded it but not much but not many people can get them. I think price-wise that would probably be the biggest concern we have. Because if it is really expensive and it costs a lot to maintain and stuff, we probably wouldn’t really be able to use it. Because price-wise, if it was kind of expensive, then it would be less appealing. | Teen | ||

| WORTH ANYTHING | Worth Anything is a sub-consideration under this cost–benefits where the benefits are considered so overwhelming that const should be a consideration—technology is worth anything | Yeah, I’m completely with [Respondent 1] and [Respondent 2] like if it is going to work I’d pretty much pay whatever because in the long term we are talking about not only healthcare saved, not only being spared from long-term complications but also being spared from long-term hospitalizations like dialysis and things that in themselves would cost you a lot of money, if not your health also. So pretty much whatever if it is a dependable system. | Adult |

| Yeah, we self fund our CGM. So yeah, we’re used to having to pay something just for the fact that sleep is priceless. | Parent | ||

| I would sell my house, wouldn’t matter, honestly. I would do whatever I had to do. | Parent | ||

| Yeah, I’m just trying to formulate an answer to that. I’d like to say money wouldn’t be an issue as long as it was improving the quality of life and it was working and doing what it was supposed to be doing. But then, realistically how much is that worth? Would I remortgage my house? Sure. | Partner |

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework of cost consideration themes reported by stakeholder groups

3.1 ∣. Policy-level themes

Participants outlined the philosophical and policy implications of costs of current diabetes technologies, namely discussing the importance of diabetes technology access for all (Table 1A).

It needs to be more equitable first of all by way of financing accessibility should be a factor and then the big picture of no one should be without healthcare and whatever they need. Okay so that is the big picture, so this coming on the market, it needs to be accessible to everybody. That’s it.

Additionally, participants emphasized that payers and policymakers need to understand that prevention with diabetes technology costs less than treatment of short- and long-term complications of diabetes. Finally, participants noted that improvements in diabetes management have been iterative over the years and across various fields with a sense of optimism.

But I think in the power of the community and the kind of medical world and the numbers can speak for themselves kind of thing, that hopefully it will be something of an offer to the under 18 at least, since they would have to do it in stages, I think they should have priority.

3.2 ∣. Organizational-level themes

Participants discussed the need to convince payers to cover diabetes technology and reported feeling frustrated with the insufficient coverage of diabetes technologies despite significant evidence existing in support of continuous glucose monitors and insulin pumps on health outcomes (Table 1B). This frustration extended to health providers and clinics where participants cited that they did not feel supported in diabetes technology use. Participants also discussed the pragmatic nature of the business of diabetes.

TABLE 1B.

Organizational level

| THEME | DESCRIPTION | QUOTE | STAKEHOLDER GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUSINESS OF DIABETES | References to business structures, private companies, the economics of businesses staying afloat | Yeah, I think the reimbursement strategy is something that can’t be left out when these companies, Bigfoot and other ones, are looking at making the systems. It is going to be critical to getting these things successful. I don’t know how it is going to work but definitely the system is going to be a lot more expensive. I think they are going to have to show the value it has to the public in these clinical studies to really get insurance companies onboard. Again, I think that is why two years is going to be hard. That is going to take a lot of time. | Adult |

| That’s a big thing for the AP systems. I guess what would they do to get insurance companies? What studies would they do to demonstrate that the insurance companies would save money through the better control of the A1C’s that would come through the use of the AP. Because I remember when they first started covering pumps for under 18. And I remember trying to get a pump before—or a CGM rather—before they would cover it under. The CGM’s before they were approved for under 18. And I mean, I guess one thing that might stop me from go getting an AP were if the insurance rigmarole that I had to go through were as horrific as—I mean at some point you just think ‘Why am I submitting all these appeals and getting all these letters?’ And I’m never going to get this project anyhow. | Parent | ||

| HCP AS A BARRIER | Healthcare providers are the perceived or stated barriers to diabetes care or diabetes technology | Don’t know about everybody else but we only have CGM because we are funding it ourselves completely. Our clinic is not interested. Every time I even mention it, they say ‘Oh no-no, we couldn’t possibly do that’. | Parent |

| The current state of health insurance, a lot of people as [Respondent 2] was just saying, some people are much less financially in a good situation and you end up with folks who are not allowed to have CGMs right now or not even allowed to have pumps because their health provider didn’t deem them necessary. That’s just insane. | Partner | ||

| We’ve just moved hospitals, because our local one refused to do CGMs. So I’m moved to [Location] because I want a CGM. I think if it was a CGM or pump; a CGM would actually be more useful for her to try to get her numbers better. | Parent | ||

| SYSTEM-LEVEL BUY IN | Needing to convince insurance, government, medical organization,anyone above the individual/family that technology is needed | I feel like my insurance would need to know that it is going to reduce their healthcare costs down the line. There needs to be scientific data saying that if people go on this, their A1C’s go down by this much and therefore they will cover it. That is my sense behind it; there’s got to be scientific backing to benefit—which isn’t going to come for a while. They are still not approving CGMs for people, which is ridiculous. | Adult |

| I want to get on my soapbox now, because that’s a real crux questions for me. If think if all of the senators and congressmen had the same insurance the rest of us did, and we had what they have, it would all be approved just like the little blue pill. | Adult | ||

| Yeah, it’s just as they say, to have a pump you’ve got to have a dedicated team at your hospital who are pro-pumps and speaking to other parents in different areas, their hospitals don’t do pumps. I think it probably changed a lot now. When [Name] first went on the pump, a lot of hospitals didn’t do them, because of the amount of work it involved. And also, you didn’t need the funding for the team to give you the back-up to work with you while you were using it. | Parent | ||

| I am a little worried about the cost of it, whether insurance would cover that, because I think initially insurance will not cover it, because it’s such a new technology, and there’s so much—there’s so many things that could go wrong with it. I think there need to be essentially test subjects, maybe people like myself that are possibly willing to go over a study of this and use the device for a while. I think they need to be programs to support that, and once there’s conclusive data that the device works and that it functions properly and people are safe, I think they’ll be able to make them smaller, more affordable, make the technology itself easier to make. And there’ll be more companies doing it. Maybe insurance will cover it. | Teen |

That’s a big thing for the AP [artificial pancreas] systems. I guess what would they do to get insurance companies? What studies would they do to demonstrate that the insurance companies would save money through the better control of the A1C’s that would come through the use of the AP.

3.3 ∣. Insurance-level themes

Insurance was discussed in six distinct constructs (Table 1C). The majority of the participants were matter of fact in their discussion of need for insurance in order to accomplish any type 1 diabetes management. Additionally, many participants discussed the perceived barriers to preferred or optimal type 1 diabetes care with public insurance.

TABLE 1C.

Insurance level

| THEME | DESCRIPTION | QUOTE | STAKEHOLDER GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEALTH RISKS FOR COVERAGE | Health risks is a sub-consideration within insurance sets parameters node where participants discuss undertaking risking behaviours to get coverage (even if hypothetical) | Yeah, I’ve got people who are in the Kaiser system who either had to manipulate their blood sugars to prove that they go low by giving themselves extra insulin and who are still fighting to get covered. They are getting better but there are people who still cannot get CGMs from Kaiser and it blows my mind. | Adult |

| I think it’s dubbed ‘non-necessary’. You have to like give yourself like hypoglycemia unawareness or significant hypoglycemia advanced, and Medicare and Medicaid, like a lot of Medicaids don’t cover it and Medicare doesn’t cover it, which is just, again, because our country it’s a tertiary prevention, instead of primary prevention, the problem is that we are just like get in some problems that could have been prevented. So, I don’t know if with the health reform | Adult | ||

| INSURANCE DICTATES MANAGEMENT | Insurance dictates management—this gets at specific negative feelings that management is limited by or at the mercy of insurance | They’ll charge us anything they can possible charge us to milk us. Any single cent they can get out of us. We’ve had I think two different, maybe three different insurance companies since [Name] was diagnosed, and they’re all awful. They’re all awful, and they’re all difficult to deal with, and they all try to get out of doing as much as they possibly can. And that’s just the way it is. That’s the name of the game. And they will try to deny this, like they tried to deny CGMs and insulin pumps before that. | Parent |

| Yeah, I mean I have often said that the worst part about diabetes isn’t the disease; it’s all this dealing with insurance. I just have absolute awful—I don’t know, insurance has been the biggest pain in the ass. I mean I’ve gotten into screaming fights with the pharmacist where I am crying because they just don’t—it is so hard to deal with that and I feel like it would take so long for insurance companies to get behind these devices. I mean you hear about people who have like intentionally had seizures in the middle of the night just so they can get on the CGM. That is how messed up our medical system is. So what would it take them to get behind that? | Adult | ||

| INSURANCE SETS PARAMETERS FOR TECHNOLOGY ACCESS | Insurance sets parameters capture any sentiment that management decisions are influenced by insurance desires | I mean with healthcare, you’re going to spend as much as you can to have the best health outcome that you can get. So if I can afford it, and it’s going to make my diabetes management better, then I’ll pay for it. Hopefully my insurance will cover it and all that stuff, so it wouldn’t be significantly more. But if it’s an improvement and I can afford it, then I’ll pay for it. If I can’t then I can’t. You can only get the healthcare that you can afford. | Adult |

| The biggest barrier would be finding access. You know I think that—I was listening to some of the comments this weekend about which device to use. Some people have a choice and some don’t really have a choice. We didn’t have choice—we didn’t have our own four choices from our insurance and then some there is a process that I am not aware—our doctor was just so great that we didn’t have problems; we just got it. She did whatever she was supposed to. I heard there had to be certain letters written and things like that, so—it needs to be more equitable first of all by way of financing accessibility should be a factor and then the big picture of no one should be without healthcare and whatever they need. Okay so that is the big picture, so this coming on the market, it needs to be accessible to everybody. That’s it. | Parent | ||

| Think the only thing for me is insurance coverage. I know there are lots of pumps out there. We only have a choice of, I think, two right now. We’re insured through Kaiser. So, that’s the only thing that I feel would get in our way is just not having access to it otherwise I can’t—he’s already wearing all these devices. I can’t see him being like I don’t want to—I don’t want to have that happening while I wear all this. | Parent | ||

| PERCEPTION OF INSURANCE-RELATED BARRIERS | Perceptions of insurance barriers to be coded when there is a mention of hypothetical barriers that different insurances may pose (i.e. MediCal has poor coverage so people with MediCal must not have diab tech) | Medicare doesn’t even cover CGMs, so if you’re over 65, you’re not going to be covered under Medicare. So, and I think that insurance companies madness, it makes me sound really like a downer. I think they’re interested in short term expenses and short term profits. And they hope that you go to a different insurance carrier when those complications happen 20 years, 30 years, 40 years down the line. They are not concerned about that. They worry about their bottom line this year. So, it’s going to be a hard sell to payers to double or triple or quadruple what they’re paying currently. And unless there’s an overwhelming pivotal study that shows that the outcomes are so much better and there’s some ground swell of JDRF hammering on all those congressmen, they’re going to try to avoid it at every turn. And AP is going to be for people that have money. And children in Africa with diabetes are not going to get artificial pancreases. It’s haves and have nots. That’s the way it’s going to be for a period of time. And then hopefully it will start trickling down. It is hard to get a sensor for a family that’s on CCS now. So, that’s going to be a problem. And UCSF and Packard both see 40% of their patient loads are CCS patients. And so, that’s going to be—and you got to get CCS to pay for it. | Parent |

| I think Medicare will take another 10 years to approve an artificial pancreas. I think everything we do with Medicare is a fight. And I think that it will have the very same fight. I think that private insurance, the employer insurance will have the same fight that we had when we had to get CGMs approved. | Adult | ||

| My insurance [Name] receives both Medicare and she’s on my insurance. But my insurance, I think, would be more flexible for payment than— | Partner | ||

| Interviewer: Medicare. | |||

| Respondent: Medicare. | |||

| RELIANCE ON INSURANCE | The concept that one requires insurance is required to get supplies and any/all aspects of management of type 1 diabetes | Respondent 2: Insurance companies are stupid. Respondent 1: If they don’t pay for it, then how am I—how are people going to afford it? | Teen |

| My nurse told me that for the insurance company to pay for a Dexcom or pump, the doctor’s office has to tell the insurance company that your diabetes is not well managed. Because if they tell your insurance company that your diabetes is well managed, they’ll say you don’t need it. | Teen | ||

| If we had to pay for it out of our own pocket, [Name] wouldn’t be having the quality of life she does now. As I say, thank God to the insurance; but as [Respondent 1] said, whatever we can do to help pay for it with her, we would do our best. The pricing is just ridiculous at times. | Partner | ||

| TIME SPENT ON INSURANCE | You have to personally take the time to make it diabetes technology or patient/provider preferred management happen | And I get—today I had seven phone calls about why my strips were needed a prior authorization. So I can only imagine in the same way that when pumps were originally out there, that it will require all kinds of work to get the companies to pay for it. I think they have a hard time seeing 20 years from now as oppose to the end of this quarter. | Adult |

| That’s a big thing for the AP systems. I guess what would they do to get insurance companies? What studies would they do to demonstrate that the insurance companies would save money through the better control of the A1C’s that would come through the use of the AP. Because I remember when they first started covering pumps for under 18. And I remember trying to get a pump before—or a CGM rather—before they would cover it under. The CGM’s before they were approved for under 18. And I mean, I guess one thing that might stop me from go getting an AP were if the insurance rigmarole that I had to go through were as horrific as—I mean at some point you just think ‘Why am I submitting all these appeals and getting all these letters?’ And I’m never going to get this project anyhow. | Parent |

Medicare doesn’t even cover CGMs. Unless there’s an overwhelming pivotal study that shows that the outcomes are so much better, they’re going to try to avoid it at every turn. And AP is going to be for people that have money.

Although many participants discussed the need for insurance to cover type 1 diabetes supplies without a positive or negative valence, when a valence was expressed, it was often negative. Participants discussed that they feel like insurance often dictates diabetes technology management of type 1 diabetes and that the covered management is not in line with patient or family preference, provider recommendations, or most up to date research.

My current insurance company doesn’t even provide great coverage for my CGM, so I wouldn’t imagine that they would be jumping right onboard with a closed loop system right now.

Participants reported times when health risks were taken in order to gain coverage.

I’ve got people who are in the Kaiser system who either had to manipulate their blood sugars to prove that they go low by giving themselves extra insulin and who are still fighting to get covered.

3.4 ∣. Interpersonal-level themes

All groups discussed the impact of type 1 diabetes and automated insulin delivery cost on their relationships with their family (Table 1D). The discussion for costs on others varied by the group, particularly by parents. Partners, adults and youth all noted that healthcare coverage has helped offset costs of type 1 diabetes management and extrapolate this prior experience to what they may expect to see with the incorporation of automated insulin delivery in the future.

TABLE 1D.

Inter-personal level

| THEME | DESCRIPTION | QUOTE | STAKEHOLDER GROUP |

|---|---|---|---|

| COST TO OTHERS | This code captures any mention of the cost to the family, household, partners or important members of participants household | It is difficult to prioritize; there’s always you get to a certain age and you’re independent, there is always something that you are saving towards whether it is for your mortgage for your first house or for your car or for something like that and worst with managing to a point of diabetes that I could afford the CGM but there is always something else that we are saving for and I can’t weigh up the pros of paying just so much for the CGM over what we were saving for. I can’t put myself before that, it is not a big a benefit enough for me. | Adult |

| My mom said that we would get it no matter what and if we didn’t have enough money, we would raise money or take it from my grandma. | Teen | ||

| GUILT ABOUT EXPENSE | Any mention specifically about guilt about the expenses of diabetes technology | How do I think she would feel? She is modest and extravagant at the same time so she would feel—I know deep down—she would feel a little bit guilty if everyone wasn’t getting one and if they didn’t have them available all over. If you go through your insurance you can get this or if you could go to Walgreen’s for 50 dollars you can get this. You can carry around a 50 dollar bill and get it for everyone that she runs into. That’s what we do—not that we’re buying other people’s medical equipment for them, but that’s what we do now. | Partner |

| Well, obviously I wouldn’t be paying for it. I’m 13 and I have about 20 bucks and that is about it. But I probably wouldn’t want to get anything that was too expensive because if it costs a lot, I would feel really guilty. I don’t know I just wouldn’t—because diabetes already costs more than not. | Teen |

We’ll cut corners in other places. Cost isn’t an issue for us. Fortunately, I can say cost isn’t an issue for us.

While adults, partners and youth discussed the guilt associated with the expense of type 1 diabetes on the family, parents never discussed this theme.

Well, obviously I wouldn’t be paying for it. I’m 13 and I have about 20 bucks and that is about it. But I probably wouldn’t want to get anything that was too expensive because if it costs a lot, I would feel really guilty. I don’t know I just wouldn’t—because diabetes already costs more than not.

3.5 ∣. Individual-level themes

Nearly all participants consistently reported weighing the perceived costs of initiating automated insulin delivery systems with its perceived benefits (Table 1E). They did so by undertaking a thought experiment of a cost–benefit analysis when considering initiation of automated insulin delivery. Although the discussion of conducting a cost–benefit analysis was ubiquitous, participants differed in which factors they considered to be important and in their conclusion of the analysis. Some concluded that the perceived benefits of automated insulin delivery, consistent with observed benefits from other diabetes technology, are so invaluable to diabetes care that the cost of automated insulin delivery is a non-issue and that automated insulin delivery is, in short, worth any cost they may pay.

I would sell my house, wouldn’t matter, honestly. I would do whatever I had to do.

Others discussed that they anticipate the costs to be too great to consider adopting automated insulin delivery in the future, stating that affordability is an imperative part of considering initiation of automated insulin delivery systems. In these participants, while some participants stated that they would not adopt automated insulin delivery systems unequivocally due to perceived cost, others qualified their affordability statement by discussing that the efficacy of automated insulin delivery systems may increase the likelihood of use.

How much better is this; so the value compared to your alternative options it sounds like. Others are doing pretty well without the expensive stuff right now. Personally, I think I stand to gain a lot with something like this and so it depends on how well does it work compared to what I am doing right now. And would I be willing to pay? Well it depends on how well it works.

Burden of cost was also considered in more concrete terms such as one-time initiation and monthly maintenance out of pocket costs.

If we had to pay for it out of our own pocket, [Name] wouldn’t be having the quality of life she does now.

Across the groups, percentage agreement between raters ranged from 86.7% to 93.8% and Kappa coefficients ranged from 0.43 to 0.64 indicating moderate agreement (Table S1). Moderate agreement means that different raters might reach different interpretations of the underlying data, but that there was an important overlap between raters’ endorsements. The strength of the kappa coefficients of agreement = 0.01–0.20 slight; 0.21–0.40 fair; 0.41–0.60 moderate; 0.61–0.80 substantial; 0.81–1.00 almost perfect.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

We report that monetary and non-monetary cost considerations were important in automated insulin delivery uptake for all four stakeholder groups, spanning the individual, their family and society at large. As diabetes technology becomes more advanced and effective, understanding the lived experience and cost considerations of automated insulin delivery systems is necessary to ensure equitable access and uptake. Participants reported their prior experiences with diabetes technology shaped their perception of automated insulin delivery adoption. The current findings extend prior reports of financial considerations10,17 to demonstrate a broad consensus that cost, as experienced by stakeholder groups, is not only a monetary issue but also includes non-monetary costs such as time, energy, costs to society, morality and interpersonal relationships. A detailed understanding of the nuances of monetary and non-monetary cost in the uptake of automated insulin delivery offers important insight on strategies to bridge the disparities seen in diabetes technology use.8

Themes such as affordability or a sense that diabetes technology is priceless describe individual-level themes, whereas the concern about the monetary cost of diabetes technology on family finances describes interpersonal themes. Insurance themes discussed the strong relationship between insurance coverage and diabetes technology access. Participants discussed the perception that public payers appear to require an overwhelming amount of evidence before they would reimburse and cover diabetes technology. This perception may stem from the lag time in covering diabetes technology that is particularly common with public insurers.13-15 The broadest themes that were discussed were organizational themes, such as the business of diabetes, and policy themes, such as access to diabetes technology for all.

Monetary and non-monetary cost as a stressor was discussed across all thematic levels (from policy-level to individual-level consideration) and by all stakeholder groups. The management of type 1 diabetes carries psychosocial burden, namely an increase in diabetes-related distress.16,23,24 These data underscore the contribution of cost to the psychosocial burden of type 1 diabetes given that cost as a stressor was discussed across all thematic levels and by all stakeholder groups. Our findings support addressing non-monetary cost for all stakeholders involved in an individual with type 1 diabetes. Incorporating discussions about guilt around type 1 diabetes cost, time spent with payers, taking health risks for coverage and insurance-related barriers during clinical encounters with youth and adults with type 1 diabetes and their families may be yet another way to decrease the psychosocial burden of type 1 diabetes.

The themes outlined in this study offer healthcare providers important insights on monetary and non-monetary cost concerns among their patients. For example, healthcare providers may overestimate financial cost of device and supplies and the impact of insurance coverage as barriers to device use. These misunderstandings can obstruct shared decision making and limit discussions about newer technologies that may have a clinical benefit.17 Although monetary cost is a concern for many families, many also report wanting to weigh the pros and cons themselves and in collaboration with their providers in their decision to start diabetes technology. Understanding this can allow medical teams instead to invest in resources to help families access technologies, assist in overcoming insurance barriers and have collaborative discussions with patients regarding their perceptions about cost as a barrier to diabetes technology uptake.

These data offer insight into the other aspects of non-monetary cost that stakeholders consider such as equity and access, cost to their relationships and time spent on assuring type 1 diabetes coverage. The time lost in phone calls and outreach to insurance companies, pharmacies and doctors’ offices to secure covered diabetes devices is itself a non-monetary cost of diabetes technology use. However, it is important to consider that inherent to spending this time required is a certain amount of health literacy to navigate the medical system as well as flexibility to make lengthy phone calls during standard business hours and work hours without threat to job and financial security. In addition to insurance coverage and monetary costs, these non-monetary costs (time spent) as well as health literacy are barriers to equitable care.

Interestingly, all stakeholder groups discussed the importance of equitable access to advanced diabetes technology as an important ethical principle and consideration in the integration of diabetes technology into the mainstream management of type 1 diabetes. Although equitable access was discussed, many also felt that diabetes technology is worth any monetary cost while acknowledging equitable access for all is limited by finances. Even among families who could more easily afford costs associated with diabetes technology, concerns about equity, accessibility and cost impacts on the overall diabetes community were important. Studies have demonstrated that disparities in diabetes technology exist by race/ethnicity8,9,25 as well as by socio-economic status.8 The policy-level themes that were discussed underscored the fact that adoption of new technology first occurs by those of higher socio-economic status.26,27 If cost as a consideration for technology uptake is left unaddressed, risks of widening gaps in diabetes outcomes through disparities in access exist. Our interpretation of these data offers an easy-to-understand framework for making technology accessible, thereby promoting wider diabetes technology incorporation and addressing the multiple dimensions of costs associated with a chronic illness.

Although nearly all themes were consistently expressed across the stakeholder groups, insurance-level barriers and guilt of type 1 diabetes cost were expressed differently by the parents of youth with type 1 diabetes. Parents reported more insurance concerns including time spent with insurance companies to receive benefits and coverage, which is characterized as a hidden cost of gaining access to diabetes technologies. Parents never reported guilt around type 1 diabetes cost despite the three other stakeholder groups’ discussions about guilt. However, excepting these two discrepancies, the remainder of the themes expressed was consistently discussed across the stakeholder groups, indicating that cost considerations were important irrespective of the stakeholder group.

Overall, there were high levels of inter-rater agreement about the mutual presence of themes in stakeholder accounts as well as mutual absences. We report Kappa coefficients indicating moderate agreement (0.43–0.64). Kappa coefficients account for raters’ agreeing by chance and are conservative measures of inter-rater agreement that may result in lower levels of agreement when there is heterogeneity among the possible codes as well as discrepancies in the coding segment size.28 Given the small sample of segments evaluated in Kappa calculations, near perfect rater agreements are not reflected and more granular considerations of data would likely elevate the Kappa coefficients.

Therefore, in addition to more standard evaluation of Kappa coefficients, qualitative research may be assessed by methodological and interpretative rigor evaluating research reliability, credibility and trustworthiness. Methodologically, the study sample is adequate and the research question and analyses are valid. Detailed documentation of the analysis process enhances replicability. External credibility and reliability are supported by researchers’ engagement with the subject matter, raters’ discussion regarding the complexity of the themes identified, and observations of similar experiences among patients and families served by our research team with rich research and clinical expertise. Our team approach and possibilities for triangulation both across researchers and across theoretical frameworks enhance the analytic generalizability of our model.29,30

The material and non-material elements of costs surfaced in this study are consistent with, though not identical to, healthcare access, insurance and psychosocial themes discussed in other research.27,31,32 The interwoven and complex nature of how people with type 1 diabetes and their families experience costs lends credibility to the study findings. Though this study is a secondary analysis, the insights provided here suggest future areas of exploration when trying to assist such families as they cope with their diagnoses and management. The multiple dimensions of costs discussed by stakeholder groups cannot readily be identified by survey or quantitative research, but may help develop scales for future assessment of multidimensional cost impacts among similar stakeholder groups.

Limitations of this study include the secondary nature of these analyses. While cost and insurance matters emerged consistently during data collection, exhaustive monetary and non-monetary cost questions and follow-up probes did not occur in most focus groups. This limitation is partially mitigated by the variety of stakeholder responses available in the dataset as well as by the pervasiveness of cost and health financing matters across all groups. Representativeness limitations stem from concerns inherent to qualitative research; however, qualitative research is an established method used to highlight and understand patterns of experience and expression across humanity and is especially useful for developing new theories or exploring underappreciated phenomena.33 Generalizability and the potential for sampling bias exist given that our study sample was predominately non-Hispanic white race/ethnicity and had higher levels of both pump and CGM use. The qualitative data were anonymized before we analysed the data and thus, we are not able to differentiate between responses from participants in the United Kingdom versus those in the United States nor by type of technology used. In addition, analyses did not account for participants’ geographical location (the United States versus the United Kingdom, or across different states/regions within each country). Findings may have varied based on state- and country-specific policies on insurance coverage and healthcare that may have influenced perceptions of cost. However, the research team's combined experience with this population contributes to their confidence that these data of costs raise important matters worthy of further exploration and discussion among diabetes researchers and practitioners.

5 ∣. CONCLUSIONS

Cost considerations for diabetes technology uptake extend beyond finances alone to include time, energy, insurance and relationship domains. Cost plays a role in contributing to disease management stress and logistics as well as one's attitude and uptake of technological advances in diabetes care. Cost also reflects an important moral principle tied to the shared desire for equitable access to diabetes technology. Knowledge of these considerations can help clinicians and researchers to promote uptake and anticipate barriers to diabetes technology use and is one strategy to bridge disparities in automated insulin delivery uptake for persons living with type 1 diabetes and their families.

Supplementary Material

What is already known?

Diabetes technology is associated with improved diabetes outcomes.

Cost is a modifiable barrier to diabetes technology use, but little is known about the nuances of cost considerations.

What this study has found?

We applied the Social Ecological Model in the interpretation of five thematic levels of cost.

Cost considerations for diabetes technology uptake extended beyond finances to include time, cost to society, morality and interpersonal relationships.

What are the clinical implications of the study?

Knowledge of cost considerations can promote equitable device uptake while anticipating barriers for all persons living with diabetes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DN conceived this study question. AA, SCS, JJW and DN conducted the analysis. AA wrote the first draft of the manuscript with contributions from SCS. AA, SCS, JJW and DN revised the manuscript with critical contributions. KDB, JWB, LML, DN and KKH are principle investigators of the INSPIRE study. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript. Drs. Addala and Naranjo are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding information

The study was funded by the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust. AA has support from the Maternal Child Health Research Institute (Ernest and Amelia Gallo Endowed Postdoctoral Fellow) and K12 (K12DK122550) at Stanford University.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

KH has research support from Dexcom, Inc., for investigator-initiated research and consultant fees from Lilly Innovation Center, Lifescan Diabetes Institute and MedIQ. The remaining authors report no relevant conflict of interest.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

REFERENCES

- 1.Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2019;21(2):66–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller KM, Hermann J, Foster N, et al. Longitudinal changes in continuous glucose monitoring use among individuals with type 1 diabetes: international comparison in the German and Austrian DPV and U.S. T1D exchange registries. Dia Care. 2020;43(1):e1–e2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergenstal RM, Garg S, Weinzimer SA, et al. Safety of a hybrid closed-loop insulin delivery system in patients with type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown SA, Kovatchev BP, Raghinaru D, et al. Six-month randomized, multicenter trial of closed-loop control in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1707–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weisman A, Bai J-W, Cardinez M, Kramer CK, Perkins BA. Effect of artificial pancreas systems on glycaemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outpatient randomised controlled trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(7):501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller KM, Beck RW, Foster NC, Maahs DM. HbA1c levels in type 1 diabetes from early childhood to older adults: a deeper dive into the influence of technology and socioeconomic status on HbA1c in the T1D exchange clinic registry findings. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(9):645–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams RN, Tanenbaum ML, Hanes SJ, et al. Psychosocial and human factors during a trial of a hybrid closed loop system for type 1 diabetes management. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2018;20(10):648–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Addala A, Auzanneau M, Miller K, Maier W, Foster N, Kapellen T, et al. A decade of disparities in diabetes technology use and HbA1c in pediatric type 1 diabetes: a transatlantic comparison. Diabetes Care. 2020;dc200257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Agarwal S, Kanapka LG, Raymond JK, et al. Racial-ethnic inequity in young adults with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2020;105(8):e2960–e2969. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naranjo D, Suttiratana SC, Iturralde E, et al. What end users and stakeholders want from automated insulin delivery systems. Dia Care. 2017;40(11):1453–1461. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajewska KA, Biesma R, Bennett K, Sreenan S. Barriers and facilitators to accessing insulin pump therapy by adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus: a qualitative study. Acta Diabetol. 2021;58(1):93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Addala A, Maahs DM, Scheinker D, Prahalad P. Loss of continuous glucose monitor coverage is associated with an increase in HbA1c. Pediatr Diabetes. 20(S28):P318. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson JE, Gavin JR, Kruger DF. Current eligibility requirements for CGM coverage are harmful, costly, and unjustified. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2020;22(3):169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Addala A, Maahs DM, Scheinker D, Chertow S, Leverenz B, Prahalad P. Uninterrupted continuous glucose monitoring access is associated with a decrease in HbA1c in youth with type 1 diabetes and public insurance. Pediatric Diabetes. 2020;21(7):1301–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barnard KD, Breton MD. Diabetes technological revolution: winners and losers? J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2018;12(6):1227–1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balfe M, Doyle F, Smith D, et al. What’s distressing about having type 1 diabetes? A qualitative study of young adults’ perspectives. BMC Endocr Disord. 2013;25(13):25. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanenbaum ML, Adams RN, Hanes SJ, et al. Optimal use of diabetes devices: clinician perspectives on barriers and adherence to device use. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2017;11(3):484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1): 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronfenbrenner U The Ecology of Human Development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 1979:352 p. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fleury J, Lee SM. The social ecological model and physical activity in African American Women. Am J Community Psychol. 2006;37(1–2):141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harper CR, Steiner RJ, Brookmeyer KA. Using the social-ecological model to improve access to care for adolescents and young adults. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(6):641–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naar-King S, Podolski C-L, Ellis DA, Frey MA, Templin T. Social ecological model of illness management in high-risk youths with type 1 diabetes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(4):785–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hood KK, Iturralde E, Rausch J, Weissberg-Benchell J. Preventing diabetes distress in adolescents with type 1 diabetes: results 1 year after participation in the STePS program. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(8): 1623–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(9):2551–2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willi SM, Miller KM, DiMeglio LA, et al. Racial-ethnic disparities in management and outcomes among children with type 1 diabetes. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):424–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott JT. The pure capital-cost barrier to entry. Review Econ Statistics. 1981;63(3):444–446. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zafar SY, Abernethy AP. Financial toxicity, part I: a new name for a growing problem. Oncol. 2013;27(2):80–149. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsu LM, Field R. Interrater agreement measures: comments on Kappan, Cohen’s Kappa, Scott’s π, and Aickin’s α. Underst Stat. 2003;2(3):205–219. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Interviews: Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2009:377. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trochim W. Research methods: the concise knowledge base. Atomic Dog Publishing. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurnat E, Moore C. The impact of a chronic condition on the families of children with asthma. - Abstract - Europe PMC [Internet]. [cited 2020 Oct 28]. Available from: https://europepmc.org/article/med/12024345 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sortsø C, Green A, Jensen PB, Emneus M. Societal costs of diabetes mellitus in Denmark. Diabet Med. 2016;33(7):877–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2007. 489 p. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.