Abstract

The actinide lanthanide separation (ALSEP) process is a modern solvent extraction approach used for the separation of the minor actinides americium and curium from the lanthanide fission products for transmutation, a process that can significantly reduce the long-term radioactivity and heat loading of nuclear waste. This process, inspired by existing chemistry, uses the aminopolycarboxylate N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediamine-N,N′,N′-triacetic acid (HEDTA) to selectively separate the actinides by stripping them from the organic phase while leaving the lanthanides behind. HEDTA is used in this separation as it has been shown to exhibit faster extraction kinetics than other aminopolycarboxylates, but its lower coordination number can allow for the formation of higher order complexes with the typically 8- to 9-coordinate f-elements. ALSEP uses a carboxylic acid buffer in the aqueous phase to control the pH of the system during metal stripping, and this buffer has the ability to complex actinide(III) and lanthanide(III) ions. The presence of a previously uncharacterized ternary lanthanide-HEDTA-citrate complex was detected during single-phase spectroscopy experiments. A combination of partitioning experiments and spectrophotometric titrations led to the identification of a 1:1:1 complex containing a partially protonated citrate ligand and determination of the stability constant of its neodymium complex.

Introduction

The separation of the transplutonium actinides americium and curium from the used nuclear fuel for transmutation applications can significantly reduce the radiotoxicity and thermal loading of the remaining fuel, relieving the strain on future waste storage facilities.1−3 The dominance of the trivalent oxidation state, the predominantly ionic bonding, and the radial contraction of the f-orbitals lead to extensive chemical similarities between the transplutonium actinides and the lanthanides, which are present as fission products in the used nuclear fuel.3,4 By exploiting small differences in the covalency of actinide (An) and lanthanide (Ln) complexes, the An(III) ions can be selectively targeted for separation.5

Solvent extraction has been identified as an ideal method for actinide/lanthanide separations due to the scalability and robustness of the technique.6 By incorporating ligands or extractants that exhibit selectivity between the actinides and lanthanides into the system, it is possible to achieve separation of the two series. One of the most common classes of the aqueous ligand employed in these solvent extraction systems is aminopolycarboxylates,7,8 whose well-defined chemistry and selectivity set them apart as attractive choices for efficient group separations of An(III) ions from Ln(III) ions.9,10

Aminopolycarboxylate complexes of the actinides and lanthanides have been studied since the 1950s, and the first example of an aminopolycarboxylate-based solvent extraction process for actinide/lanthanide separation was published in the 1960s.11,12 The strong chelating power of aminopolycarboxylates led to their use in radiochemical separations, as chelators to treat accidental ingestion of metal ions, and as complexants for radiopharmaceuticals.13 The class of aminopolycarboxylate ligands offers a range of stabilities, kinetics, and thermodynamics, thanks to the different denticities and functionalities of different aminopolycarboxylates.10 Depending on the application, aminopolycarboxylate ligands that exhibit certain characteristics, such as fast kinetics for industrial processes or large differences in complex stability, may be required. The presence of both oxygen and nitrogen-based functionalities in aminopolycarboxylate ligands allows the formation of strongly chelated complexes with both the actinides and lanthanides. The nitrogen-donating amine groups within the aminopolycarboxylate backbone afford enhanced stability of the more covalent actinides through these soft-donor interactions, and this difference in complex stability is exploited in separation processes to selectively target trivalent actinides.14

The large metal centers of actinide and lanthanide cations are most commonly eight to nine coordinate, which allow for the formation of higher order f-element complexes in systems where there may be additional aqueous complexants present. One example of this phenomenon is observed in actinide/lanthanide separation systems that incorporate an aqueous phase containing both a carboxylic acid buffer and an aminopolycarboxylate ligand.15,16 As such, deprotonated carboxylic acids are also well-known ligands for the lanthanide and actinide elements. They are smaller ligands that generally form mono-, di-, or tri-dentate complexes with actinide and lanthanide cations. While complexes of the f-elements with aminopolycarboxylate or carboxylate ligands are well documented, ternary metal-aminopolycarboxylate-carboxylate complexes are much less studied.17 As solvent extraction processes turn to smaller, more labile aminopolycarboxylate complexes in an effort to enhance the kinetics of separation, the likelihood of ternary complex formation with f-element cations increases, leading to a greater need of understanding this class of complexes.

The actinide lanthanide separation (ALSEP) process is a modern solvent extraction process currently formulated to achieve actinide/lanthanide separation through the use of N-(hydroxyethyl)-ethylenediamine-N,N′,N′-triacetic acid (HEDTA) in the presence of a citric acid buffer (Figure 1).18,19 The use of HEDTA in this process over the larger, octadentate diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) ligand was chosen in an effort to enhance the kinetics of metal partitioning across the phase barrier.8 However, one consequence of using HEDTA in this separation process is the potential formation of ternary metal-HEDTA-buffer complexes that could alter the baseline kinetics of the metal-HEDTA complexes.15,16 The predecessors of the ALSEP process generally opted to use the bulkier DTPA ligand, which is octadentate and will occupy the entire metal coordination sphere leaving no room for the formation of a ternary species.20 Though the formation of ternary f-element complexes with HEDTA and a secondary ligand is known, reports of investigations into the thermodynamics of these complexes are relatively sparse.15,16 Lanthanide-HEDTA-lactate and lanthanide-HEDTA-malonate complexes have been identified, but no literature exists examining the metal-HEDTA-citrate complexes that are likely to form within the ALSEP process. Studies of such ternary complexes are important because speciation models of the ALSEP process currently omit what we find to be the predominant aqueous metal-containing species under the conditions used for An/Ln separation in the ALSEP process.21

Figure 1.

Molecular structures of the ligands HEDTA and citric acid.

In this work, we studied the Nd-HEDTA-citrate complex formed during the ALSEP stripping step. Neodymium was used in this work as a representative fission product lanthanide and a non-radioactive size analogue for Am (crystallographic radius Nd(III) 1.107 Å, Am(III) 1.106 Å for CN = 8).22 Neodymium was also chosen for its relatively intense 4I9/2 → 4G5/2, 2G7/2 (580 nm) and 4I9/2 → 4S3/2, 4F7/2 (755 nm) optical transitions that are very sensitive to changes in the Nd coordination environment, leading to distinct absorbance spectra for different neodymium complexes that are ideal for spectral analysis.23,24 In this work, the Nd complexes formed under ALSEP stripping conditions were measured by both spectrophotometric titrations and metal partitioning experiments. Equilibrium partitioning experiments were used to give insight into the stoichiometry of the species and identify the degree of protonation of the complex.25,26 Spectrophotometric titrations under different conditions were used to confirm the stoichiometry determined from the extraction experiments and calculate the stability constant of the ternary complex in this system, which will allow for the development of more accurate speciation models for the HEDTA/citrate ALSEP system.

Results

Preliminary Identification of a Ternary Complex in the HEDTA–Citrate ALSEP System

Optical absorption spectroscopy of aqueous Nd-HEDTA solutions provided the initial evidence for the formation of a ternary complex in the aqueous phase of the ALSEP strip step (Figure 2). Spectroscopic measurements in this work focused on the optical transitions of Nd(III) complexes centered at 580 nm (4I9/2 → 4G5/2, 2G7/2) and 755 nm (4I9/2 → 4S3/2, 4F7/2) as these bands display clear changes for different metal coordination environments. The spectra obtained for solutions of Nd containing either HEDTA (Figure 2, spectrum B) or citrate (Figure 2, spectrum C) are both unique from the spectra obtained for solutions of Nd containing both HEDTA and citrate (Figure 2, spectrum A), which is representative of the aqueous phase of the ALSEP process strip solution (0.125 M HEDTA/0.2 M citrate).8,27 Furthermore, the spectrum obtained for the system containing both HEDTA and citrate cannot be produced through linear combinations of the spectra obtained for Nd-HEDTA and Nd-citrate, suggesting that the ALSEP solution contains at least one unique complex.

Figure 2.

UV–visible absorption spectra from 550 to 610 nm and 710 to 770 nm of aqueous Nd(III) solutions containing (A) 0.1 M HEDTA and 0.4 M citrate at pH 3.75 (vertically offset by 13 units), (B) 0.1 M HEDTA at pH 3.75 (vertically offset by 8 units), (C) 0.4 M citrate at pH 3.75 (vertically offset by 4 units), and (D) 0.2 M nitric acid (no offset).

Evidence supporting the formulation of the unique complex present in the solutions containing HEDTA and citrate as a ternary complex containing both HEDTA and citrate ligands came from equilibrium solvent extraction experiments conducted in an effort to assess the stoichiometry of the equilibrium ALSEP complex in the aqueous phase of the stripping step. These experiments measured the distribution ratio (D = [M]org/[M]aq) of solutions where either HEDTA or citrate concentrations varied from 0.025 to 1.0 M (HEDTA) or 0.1 to 1.0 M (citrate), while the concentration of the other ligand was held constant at a fixed pH. The relationship between the logarithm of the distribution ratio and the logarithm of the component concentration produces lines with slopes representative of the average stoichiometry of the varied component in the equilibrium complexes (Figure 3).28 The results from these slope analysis experiments for both Nd and Am are summarized in Table 1. They indicate an average 1:1:1 metal:HEDTA:citrate stoichiometry in the equilibrium aqueous phase complex. The modest deviations from the integral slopes of −1 expected for the formation of 1:1 complexes in the aqueous phase are attributable to changes in the activity coefficients of the aqueous species as the ionic strength of the aqueous solutions was not controlled in these experiments, while the HEDTA concentration varied across more than 1 order of magnitude.21

Figure 3.

Variation in the Nd and Am distribution ratios as the concentration of HEDTA or citrate is changed. For all experiments, the organic phase consisted of 0.75 M HEHEHP and 0.05 M TEHDGA in n-dodecane pre-equilibrated with an aqueous citric acid solution at pH 3.75. The aqueous phase concentrations were 0.025 to 1.0 M HEDTA with 0.4 M citrate at a pH of 3.75 or 0.1 to 1.0 M citrate with 0.1 M HEDTA (Nd) or 0.25 M HEDTA (Am) at a pH of 3.75.

Table 1. Slope Analysis Results for the Log–Log Plots of Nd and Am Distribution Ratios vs Concentration of HEDTA or Citrate (Figure 3) for the Determination of the ALSEP Equilibrium Complex Stoichiometry.

| varied component | metal | slope | intercept |

|---|---|---|---|

| HEDTA (0.025–1.0 M) | Am | –0.90 (6) | –1.63 (6) |

| Nd | –0.86 (5) | –0.54 (6) | |

| citrate (0.1–1.0 M) | Am | –1.0 (1) | –1.50 (6) |

| Nd | –1.0 (1) | –0.15 (6) |

Protonation State of the Ternary Complex

Citrate and HEDTA exist in multiple protonated states between pH 3 and 4, where the ALSEP process is intended to operate (Figure S1).29 This suggests the potential for protonated ternary complex formation. The HEDTA ligand is fully deprotonated when complexed with an actinide or lanthanide metal center;30 however, citrate is known to form protonated complexes with Ln(III) and An(III) species under certain conditions.17,31 A modified solvent extraction procedure adapted from the work of Shanbhag and Choppin25 was used to identify the protonation state of the ternary complex (Supporting Information). In these experiments, distribution ratio measurements were made on sets of solutions with varied total citrate concentrations. The pcH (pcH = −log molar H+ concentration) of each set of citrate solutions was held constant, but the pcH of different sets varied between pcH 2.50 and 3.50. Then, the apparent equilibrium constant for the hypothetical addition of citrate to Nd(HEDTA) by the equilibrium

| 1 |

or K1app (Supplemental Information), was calculated at each pcH as previously described.32 The apparent equilibrium constants vary with acidity, showing a 1.06 ± 0.14 power dependence (Figure S2). This indicates that one H+ is consumed in the formation of the ternary complex from Nd(HEDTA) and the citrate trianion, cit3–, according to the equilibrium

| 2 |

The involvement of a single proton in the ternary metal complex is also supported by the spectrophotometric pcH titration (vide infra). Equilibrium 2 can also be expressed as a reaction between Nd(HEDTA) and Hcit2–,

| 3 |

with equilibrium constant K111, or in terms of the stability constant β1111, by the equilibrium

| 4 |

Regardless of the form of the equilibrium, the ternary An(III)/Ln(III) complex formed in the aqueous phase of the HEDTA–citrate implementation of the ALSEP process strip is a 1:1:1:1 M3+:H+:HEDTA3–:cit3– species.

Spectrophotometric Titrations

Spectrophotometric titrations of solutions containing Nd, HEDTA, and citrate in 1 M NaNO3 were conducted to determine the formation constant of the ternary Nd complex (Figures 4 and S3–S6). Titrations were conducted by adding citrate-containing solutions to solutions containing Nd and HEDTA at constant pcH, adding HEDTA to solutions containing Nd and citrate at constant pcH, and adding NaOH to acidic solutions containing Nd, HEDTA, and citrate (Table S1).

Figure 4.

UV–vis spectra for the spectrophotometric titration of 0.02 M Nd/0.10 M HEDTA/0.20 M citrate/1.0 M NaNO3 by NaOH between pcH 0.73 and 4.03 (Titration 5, Table S1) from 560 to 610 nm and 710 to 770 nm, with a close-up view of the peaks between 570 and 590 nm and 730 and 750 nm.

To build an appropriate speciation model to fit the experimental data, the number of unique light-absorbing species was determined for each titration using three different approaches implemented in the programs MCR-ALS 2.0, SixPack, and TRIANG.33−35 For the three titrations of citrate into Nd(HEDTA) solutions, all three approaches used to determine the number of unique light-absorbing species indicated two unique light-absorbing species. The spectra for these two species calculated by the MCR-ALS code match the spectra of Nd(HEDTA) and the proposed ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– species shown in Figure S7. This result is consistent with the multitude of well-defined isosbestic points present throughout each citrate titration (Figures S3–S5). The spectra from the spectrophotometric titration of HEDTA into Nd-citrate solutions were also able to be represented by two unique light-absorbing species, whose MCR-ALS-generated spectra closely resemble the spectrum of Nd in a citrate-only system and the spectrum proposed for the ternary complex (Figure 2, spectrum A). Again, well-defined isosbestic points persist throughout the entire titration, consistent with the presence of only two light-absorbing species (Figure S6).

In contrast, no isosbestic points persist throughout the spectrophotometric pcH titration (Figure 4) and all three programs indicated the presence of four unique light-absorbing species (Figure 5), with the fourth species making only a small contribution to the overall fit of the spectra. This suggests that the fourth species contributes little to the observed absorption spectra under our titration conditions. Nevertheless, the model-independent spectra of the four species derived from the MCR-ALS analysis of the pcH titration spectra are clearly identifiable. The spectra of three of the species match those of Nd3+ in 1 M NO3– media, Nd(HEDTA), and a set of Nd-citrate species similar to Figure 2, spectrum C. This leaves only one unique neodymium-containing species unidentified for the ternary complex, and the MCR-ALS-generated spectrum of that species matches Figure 2, spectrum A as well as the spectra of the second light-absorbing species derived from the citrate and HEDTA titrations.

Figure 5.

Model-independent speciation diagram of the neodymium-containing species present the spectrophotometric pcH titration (Figure 4) as calculated by MCR-ALS. The spectra calculated for each of the four species identify them as (dashed-dotted line) Nd(III) in 1 M HNO3, (dotted line) Nd-citrate species, (dashed line) Nd(HEDTA), and (solid line) the ternary species Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2–.

The spectrophotometric titrations also corroborate the ternary complex stoichiometry derived from the solvent extraction experiments. The concentrations of Nd(HEDTA) and the ternary complex derived from the MCR-ALS analysis of the pcH titrations (Figure 5) were used to check the citrate stoichiometry of the ternary complex against the general equilibrium

| 5 |

with equilibrium constant

| 6 |

which gives the citrate stoichiometry as the slope c of the line,

| 7 |

The pcH titration data gave a line with a slope of 0.96 ± 0.03 and an intercept of 2.46 ± 0.08 (Figure S8), confirming the participation of one molecule of citrate in the ternary complex.

The proton stoichiometry of the ternary complex was also further verified by two approaches to analyzing the spectroscopic titration data. First, the concentration of the ternary complex determined from the model-independent MCR-ALS analysis of the spectrophotometric pcH titration data for 22 different solution pcH values (Figure 5) was compared to thermodynamic equilibrium speciation models for the formation of Nd(HEDTA)(HxCit)3–x with x = 0, 1, or 2. Consistent with the pcH dependence of the apparent equilibrium constants seen in the solvent extraction data, only equilibrium models of the formation of Nd(HEDTA)(HCit)2–, which is the x = 1 ternary complex formed from HCit2–, are able to reproduce the observed ingrowth of the ternary complex as the pcH is increased (Figures 6 and S9). The pcH dependence of the x = 0 model, where Nd(HEDTA)(Cit)3– would be formed, is too steep between pcH 2.3 and 3.0, and it under-predicts the concentration of the ternary complex by an order of magnitude at low pcH (Figure S9). On the other hand, testing the x = 2 case, which features H2Cit– as the ternary ligand, greatly over-predicts the amount of the ternary complex observed at low pcH, the variation in the concentration of the ternary complex with pcH does not match the concentration profile observed (Figure 6), and the modeled ternary complex dissociates above pcH 3.2 as the concentration of H2cit– begins to decrease (Figure S1).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the formation of ternary Nd-HEDTA-citrate complexes measured in a spectrophotometric pcH titration with predictions from optimized equilibrium models for different degrees of citrate protonation. (circle) Concentration of the ternary complex determined by the model-free MCR-ALS analysis of spectra; best-fitting concentration profiles of ternary complexes determined from equilibrium thermodynamic models for the formation of (blue dashed line) x = 0 Nd(HEDTA)(cit)3–, (red solid line) x = 1 Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2–, and (black dotted line) x = 2 Nd(HEDTA)(H2cit)−.

A second approach to confirming the proton stoichiometry of the ternary complex tested the fit of the spectrophotometric citrate titrations to equilibrium models involving coordination of a single H2cit–, Hcit2–, or cit3– anion in the ternary complex. The citrate spectrophotometric titrations were fit using the program SQUAD36 to equilibrium models that included all the equilibrium species defined in Table S2 for the Nd-HEDTA-citrate system plus a single ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hxcit)x−3 species with x = 0, 1, or 2. Similar to the solvent extraction experiments, this resulted in apparent stability constants, β, for the equilibria

| 8 |

at three different pcH values. The apparent stability constant for the x = 1 complex (Figure 7) is nearly independent of the acidity, implying that Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– is the ternary complex formed. Furthermore, the linear regression analysis of the variation in the apparent stability constants of the x = 0 case shows a slope of 0.82 ± 0.06 with respect to changes in H+ concentration, while the x = 2 case shows a slope of −1.16 ± 0.05. These slopes also fully support the formation of Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– by Equilibrium 4 and

| 9 |

rather than the formation of either Nd(HEDTA)(cit)3– or Nd(HEDTA)(H2cit)−.

Figure 7.

The apparent stability constant calculated for Equilibrium 8 by SQUAD from the three citrate titrations for the formation of Nd(HEDTA)(Hxcit)x−3 is only independent of pcH when x = 1. (square) x = 0, (circle) x = 1, and (triangle) x = 2.

Additionally, SQUAD fitting of the spectrophotometric titrations with mixtures of either the x = 0 and x = 1 or the x = 1 and x = 2 Nd(HEDTA)(Hxcit)x−3 complexes was conducted in an effort to probe the possibility of mixtures of two different protonation states for the ternary species; however, the fits would not converge, and the titration data could not be fit with equilibrium models involving more than one protonated ternary complex.

All five spectrophotometric titrations with 652 wavelengths per solution were combined into a single input file encompassing three citrate titrations at pcH 3.00, 3.50, and 4.00, an HEDTA titration at pcH 3.00, and data from the pcH titration from pcH 1.75 to pcH 4.03 at a constant ratio of total Nd:HEDTA:citrate concentrations. The data was fit to the equilibrium model defined by the constants in Table S2 and β1111 for Equilibrium 4, which was the only equilibrium constant varied in the fit. The known molar absorptivities of Nd(III) in 1 M NO3– media and Nd(HEDTA) were also used as inputs to the program, while the molar absorptivities of Nd-citrate and the ternary complex were allowed to float. The experimental spectra were well reproduced by a stability constant for the ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– complex of log β1111 = 22.15 ± 0.05 (Figure 8 and Table 2). Given the pKa values of citric acid and the stability constant of Nd(HEDTA) (Table S2), this β1111 value for Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– corresponds to log K111 = 2.41 ± 0.05 for Equilibrium 3. This is in excellent agreement with the equilibrium constant derived from the MCR-ALS treatment of the spectrophotometric pcH titration data, 2.46 ± 0.08 (vide supra). The agreement between the SQUAD-calculated spectrum of Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– from the complete set of spectrophotometric titrations, the experimentally measured spectrum of Nd-HEDTA-citrate mixtures, and the MCR-ALS-generated spectrum attributed to the ternary species further validates the SQUAD results (Figure 9). MCR-ALS calculates the spectra of the light-absorbing species within a system without any information regarding their identity or the system’s conditions and also adjusts the spectra of all the light-absorbing species, not just the ternary complex spectrum, to optimize the titration fit. The fact that the MCR-ALS output for the ternary complex is a nearly perfect match for the robustly calculated spectra from the SQUAD computation reinforces the strength of the SQUAD results and validates the accuracy of the calculated molar absorptivities and stability constant.

Figure 8.

Results of SQUAD fitting for the pcH 3.0 citrate spectrophotometric titration. Absorbance values at selected peak wavelengths with symbols representing experimental data and lines representing the SQUAD-calculated absorbances for the best-fitting model (log β1111 = 22.15, log K111 = 2.41). The wavelengths depicted are (square) 580.0 nm, (circle) 585.0 nm, (up-pointing triangle) 732.2 nm, (down-pointing triangle) 734.2 nm, (diamond) 735.6 nm, and (left-pointing triangle) 746.0 nm.

Table 2. Equilibrium Constants for the Formation of the Ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– Complex Calculated from the SQUAD Analysis of the Spectrophotometric Titrations.

| equilibrium | |

|---|---|

| Nd3+ + H+ + HEDTA3– + cit3– ⇌ Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– | log β1111 = 22.15 ± 0.05 |

| Nd(HEDTA) + Hcit2– ⇌ Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– | log K111 = 2.41 ± 0.05 |

Figure 9.

Comparison of the spectra for the ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– complex identified by (A) SQUAD analysis of all five spectrophotometric titrations outlined in Table S1 (vertically offset by 6 units), (B) MCR-ALS analysis of the pcH titration (vertically offset by 3 units), and (C) mixing 20 mM Nd(NO3)3, 0.1 M HEDTA, and 0.2 citric acid at pcH 4.00 (no offset).

Discussion

Replacing DTPA with the aminopolycarboxylate HEDTA as the actinide-selective aqueous ligand in the ALSEP process enhances the metal partitioning kinetics in the stripping step thanks to the smaller chelator’s faster complex formation and dissociation kinetics.8 However, in the presence of the high concentrations of citric acid buffer used in the ALSEP process, An(III) and Ln(III) metal centers form a previously uncharacterized metal-HEDTA-citrate complex. The presence of this ternary complex as the predominant metal equilibrium species in the aqueous phase also has unexpected consequences on the kinetics of metal phase transfer in the system.37 The experiments described in this work aim to characterize both the protonation state and thermodynamic stability of this complex, which will allow for more accurate modeling of these systems.

Spectroscopic experiments and slope analysis of distribution ratios vs component concentrations under ALSEP conditions led to the preliminary identification of the previously uncharacterized ternary complex between Nd, HEDTA, and citrate. Neodymium, which is generally 9-coordinate in aqueous solution,38,39 is able to form higher order complexes when relatively small ligands are present in solution. HEDTA, which is likely hexadentate due to the ability of the 2-hydroxyethyl arm to coordinate to the metal center,40 will only partially occupy the binding sphere of the metal center.41 Because HEDTA occupies at most six of the nine potential inner coordination sphere binding sites of Nd, there is ample room for another small molecule to displace some or all of the remaining water molecules coordinated to the metal center. Furthermore, unlike the EDTA4– or CDTA4– complexes of the trivalent f-elements, Nd(HEDTA) is neutral instead of bearing a negative charge like Nd(EDTA)− or Nd(CDTA)−, so the coordination of a negatively charged secondary ligand, such as citrate, to the metal center will be less hindered as there will not be electrostatic repulsion between two anionic species, which would inhibit ternary complex formation. The presence of substantial concentrations of citrate in the proposed ALSEP stripping step leads to its coordination to the Nd-HEDTA complex, resulting in the formation of the ternary Nd-HEDTA-citrate species. Evidence for the inner-sphere nature of citric acid coordination is observed in spectrum A in Figure 2, which reflects a unique species that cannot be reproduced by a linear combination of Nd-HEDTA and Nd-citrate spectra. Furthermore, the results of the solvent extraction experiments also show that the trivalent actinide cation Am3+ forms a ternary 1:1:1 Am:HEDTA:citrate complex similar to that of Nd.

With the full metal:ligand stoichiometry of the ternary complex identified, it is important to determine the protonated states of the ligands in the complex. Previously, only fully deprotonated HEDTA complexes with the lanthanides have been reported, with no evidence to support the formation of partially protonated metal-HEDTA complexes.10,42 Because HEDTA is relatively large and forms multiple chelate rings when fully coordinated, the chelation effect experienced when metal-HEDTA complexes form affords greatly enhanced stabilization of the complex. Protonating any single site on the HEDTA molecule reduces the stability of the complexes. In fact, kinetic investigations into aminopolycarboxylate complexes suggest that the fastest pathway for complex dissociation involves protonation of the ligand.43,44 In combination with the known propensity for citrate to form protonated complexes with trivalent f-element cations, such as M(Hcit)+ and M(Hcit)(cit)2–,17 the acidic proton present in these ternary complexes therefore appears to be associated with one of the citrate carboxylate groups.

Confident of the identity of the ternary complex as Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2–, the logarithmic stability constant was identified as 22.15 ± 0.05 by fitting the spectrophotometric titrations. The experiments used to obtain this equilibrium constant included different starting conditions that represented the different possible neodymium complexes within the system. For the citrate titrations at pcH 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0, the titrations were determined to contain two unique light-absorbing species: the starting species, Nd(HEDTA), and the ternary species Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2–, suggesting that in these titrations, the addition of Hcit2– results in its direct association with the existing Nd(HEDTA) complex to form the ternary species. For the HEDTA titration at pcH 3.0, the only two unique light-absorbing species in the titration were identified as the starting Nd-citrate species, which likely included both Nd(cit) and Nd(Hcit)+ in a nearly constant ratio that could not be deconvoluted spectroscopically, and ternary Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2–. In this HEDTA titration, the formation of the ternary complex by the association of HEDTA3– with the existing Nd(Hcit)+ represents the pathway for ternary complex formation. The pcH titration represents the most complex speciation of all the titrations studied with four unique absorbing species representing appreciable fractions of Nd under some conditions (Figure 5). From pcH 0.77 to pcH 1.5, the predominant species is a mixture of Nd3+ and Nd(NO3)32+, at pcH 1.5, a small amount of the Nd3+ (approx. 20%) has complexed with Hcit2–, and after pcH 2.0, the Nd, Nd(NO3)2+, and Nd(Hcit)+ concentrations decrease substantially as Nd(HEDTA) and Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– are formed. Nd(HEDTA) is the predominant complex between pcH 1.5 and pcH 2.75, but observable amounts of the ternary complex begin to appear at pcH 2.0 as measurable amounts of Hcit2– begin to form in the solution (Figure S2). Upon reaching pcH 2.75, Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– becomes the predominant Nd species.

The identification of this ternary complex in the ALSEP system is not the first example of a ternary metal-HEDTA-buffer complex in an actinide/lanthanide separation system. Metal-HEDTA-lactate and metal-HEDTA-malonate complexes were characterized previously by Braley et al. and Lapka et al., respectively.15,16 These complexes were investigated as efforts to improve the kinetics of the TALSPEAK solvent extraction system shifted toward the use of HEDTA as a replacement for DTPA. For the ternary complexes of M(HEDTA) with buffer molecules, the stability constants increase in the order of lactate < malonate < Hcit2–. This order is consistent with the increasing strength of the 1:1 metal:ligand complexes formed between either Nd (citrate, lactate, and malonate) or Am (malonate) with the different buffer complexes.

Our ternary citrate complex is the first of its kind to involve a partially protonated buffer molecule. Lactic acid is a monoprotic, monodentate ligand that is incapable of complexing to the metal center in its protonated state. Malonate is diprotic and bidentate and theoretically could bind through just one of its carboxylate moieties, while the other one remains protonated, but then it would lose the enhanced stability afforded by the chelation effect, weakening the complex significantly. Unlike malonate, citric acid, a triprotic, polydentate ligand, can complex through two of its three carboxylate functionalities, while the third remains protonated, and it will still exhibit the added stability afforded by the chelation effect allowing for a complex with a stability constant of the same order of magnitude as that of the metal-malonate complex.16,17

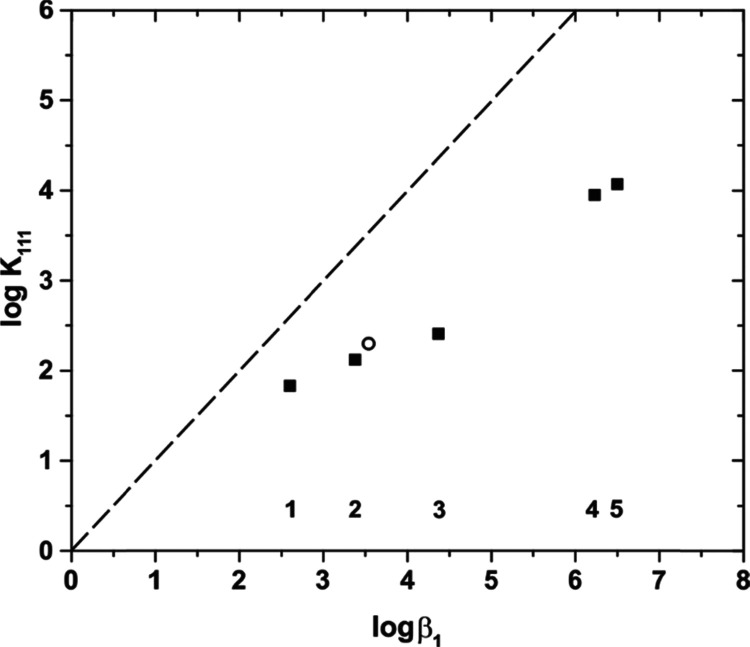

Additional ternary complexes of HEDTA with actinides and lanthanides and other ligands have also been reported and characterized.45−47 Though the secondary complexants in these ternary complexes are not viable alternatives to the citric acid buffer for ALSEP applications, their greater complexing strength compared to that of lactate or malonate allows for more direct comparisons to the ternary metal-HEDTA-citrate species. Ternary complexes of the potentially tridentate ligand imidodiacetic acid (IMDA), bidentate adenosine-5′-triposphate (ATP), and tetradentate nitrolotriacetic acid (NTA) with Nd(HEDTA) or Am(HEDTA) have been reported and characterized. Unlike lactate or malonate, these complexants are all stronger ligands than citrate and have binary stability constants greater than that of Nd(Hcit)+. Consequently, they are all likely to form more stable ternary complexes with M(HEDTA). Though the overall stability constants are greater than Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– for M(HEDTA)(L) where L = IMDA, ATP, or NTA, the increase in complex stability for the ternary complexes (K111) is less than that for the formation of simple binary M-L complexes. The data summarized in Figure 10 for different M(HEDTA)L complexes illustrates this relative change in stability when the secondary ligand is added to a M(HEDTA) complex compared to the stability of its binding directly to the aqua cation of the same metal. Additionally, this difference in stability for ligand addition increases as the ligands themselves increase in strength. For lactic acid, the value of log β1 is 0.77 log units greater; for Hcit2–, this difference is 2.0 log units; and for IMDA, this difference is 2.43 log units. This change in magnitude of stability constant difference is a consistent trend across the series and can be represented by a linear relationship with a slope of 0.63 ± 0.02 for the data set. Because these secondary ligands increase in size and bulk as they increase in 1:1 complex strength, it appears that increased steric strain is responsible for the progressively larger deviation in K111 values when complexing a metal center already partially occupied with an HEDTA molecule. The ternary citrate complex falls in the middle of the known M(HEDTA)(L) complexes in terms of stability and represents a balance afforded by the fact that citric acid is a strong ligand with few bulky groups and a degree of steric flexibility.

Figure 10.

Linear free energy relationship between the stability of 1:1 Nd and Am complexes48 and the formation of ternary M(HEDTA)L complexes in the equilibrium M(HEDTA) + L ⇋ M(HEDTA)L. M = (square) Nd or (circle) Am. L = (1) lactate,15 (2) malonate,16 (3) Hcit2–, (4) adenosine-5′-triphosphate,47 and (5) iminodiacetate.45 The dashed line represents a slope of 1 for reference.

Conclusions

The use of HEDTA as an aqueous ligand in solvent extraction separations has been shown to improve the mass transfer kinetics. Processes such as ALSEP use high concentrations of carboxylic acid buffers such as citric acid to facilitate metal transfer, but in HEDTA-based systems, citrate also acts as a complexing ligand, forming the ternary M(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– complexes with An(III) and Ln(III) ions. Characterization of this ternary complex led to the identification of a partially protonated Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– species, with a log β1111 of 22.15.

The confirmation of this protonated ternary complex in the aqueous ALSEP strip solutions allows for the potential to improve our understanding of the ALSEP process. Identification and characterization of relevant ternary metal-HEDTA-buffer complexes are essential for the further development of these actinide/lanthanide separations. As research in actinide/lanthanide separations shifts toward speeding up separations, which is what led to the use of HEDTA as a ligand with faster complexation kinetics, the relevant equilibrium chemical species must be understood before the mechanisms of metal phase transfer and the different roles these chemical components play in facilitating these reactions can be uncovered. As we have seen for the previously known M(HEDTA)(L) complexes and the Nd(HEDTA)(Hcit)2– species, the identity of the secondary ligand directly impacts the stability of the complex, which can, in turn, affect the complexation kinetics of formation and dissociation for these ternary species and the kinetics of the overall solvent extraction process. Therefore, the buffer must be taken into consideration for future iterations of processes aiming to achieve faster kinetics of separation.

Methods

Materials

Caution! Am-241 is radioactive (t1/2 = 432 y) and emits both α- and γ-radiation. It must be handled in properly equipped and monitored radiological facilities.

Aqueous phases were prepared using 18 MΩ DI water, and organic phases were prepared using anhydrous n-dodecane (99%, Sigma Aldrich). The organic extractant HEHEHP (Carbosynth) was purified to 98% HEHEHP/2% bis(2-ethylhexyl)phosphoric acid (HDEHP) using the third phase purification method as previously described.49 The secondary organic extractant TEHDGA (99%, Eichrom) was used as received. HEDTA (99%, Sigma Aldrich), citric acid (99.5%, Sigma Aldrich), and sodium nitrate (99% Sigma Aldrich) were used as received to prepare the aqueous phases. Neodymium solutions were prepared from a standardized stock solution of Nd(NO3)3 as described previously.49 Americium solutions were prepared from a radiochemically pure Am-241 stock solution at 2 μCi/μL in 1 M HNO3 (Am was sourced from Eckert & Zeigler). Except for the liquid–liquid extraction experiments used to verify the citrate and HEDTA stoichiometry of the aqueous complexes, the ionic strength of the aqueous solutions was controlled by adding 1 M NaNO3 to minimize changes in activity coefficients.

The acidity of the aqueous phases was adjusted as needed using NaOH (50 w/w% solution, certified, Fisher Chemical) and trace-metal grade nitric acid (Ultrex II, J.T. Baker). The acidities of solutions used for the HEDTA and citrate distribution ratio experiments to determine ligand stoichiometry were measured using a Ross Orion semimicro pH electrode calibrated with commercially available pH 4.00 and pH 7.00 buffers. Solutions used in the protonation determination experiments and the spectrophotometric titrations were adjusted to the desired pcH after calibrating the electrode by titrations of standardized HNO3 with NaOH at the appropriate ionic strength.

Organic phases prepared for solvent extraction experiments consisted of 0.75 M HEHEHP and 0.05 M TEHDGA for the complex stoichiometry investigations, while the organic phases used for the complex protonation determination experiments contained only 0.75 M HEHEHP. These organic phases were pre-equilibrated using citric acid buffer at the appropriate acidity, with two contacts at a 2:1 aqueous:organic volume ratio.

Solvent Extraction Experiments

Equilibrium distribution ratios were obtained by contacting equal volumes of the appropriate organic and aqueous solutions for 20 min on a vortex mixer at room temperature (23 ± 2 °C) or for 24 h on a thermostat-controlled shaker (25.0 ± 0.1 °C). Samples were removed, and the phases were separated by centrifugation for 60 s. The americium-containing samples were separated, and both the aqueous and organic phases were sampled and the Am content was quantified by gamma spectroscopy. The neodymium samples were separated, the aqueous phases were sampled and diluted, and the Nd content of the aqueous phases before and after extraction was quantified via ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Optima 5300 DV).

Distribution ratios were measured in duplicate for all samples. For the HEDTA and citrate experiments to determine complex stoichiometry, the concentration of HEDTA or citrate was systematically varied across 1 order of magnitude. For the experiments determining the degree of protonation of the aqueous complexes, the citrate concentration was varied from 0 to 0.5 M at different pcH values between 2.5 and 3.5.

Spectrophotometric Titrations

Spectrophotometric titrations were carried out using Varian Cary 300 and Cary 5E spectrophotometers with 1.000 cm quartz cuvettes between 550 and 620 nm (Cary 300) and 710–780 nm (Cary 5E) at 0.2 nm resolution. The titration conditions are summarized in Table S1. Experiments were designed to minimize changes to the solution composition in order to improve the accuracy of the calculated stability constant. Samples were stirred in a thermostatically controlled water bath set to 25.0 ± 0.1 °C, and the pcH of the system was monitored continuously. The spectra from both wavelength regions of the spectrophotometric titrations were combined and baseline-corrected for each sample. For each experiment, the number of unique light-absorbing species being formed was determined using three different approaches implemented in the programs MCR-ALS 2.0, SixPack, and TRIANG.33−35 Stability constants were calculated from the spectrophotometric titration data using the program SQUAD36 with known molar absorptivities of Nd3+ and Nd(HEDTA) complexes, and equilibrium constants for relevant HEDTA and citrate species (Table S2) were included in the calculations. All uncertainties are given at the 95% confidence level.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Energy Office of Nuclear Energy under award number DE-NE0008554. The authors would like to thank Dan McAlister and Eichrom Technologies for providing the TEHDGA extractant used in solvent extraction experiments.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c00759.

Description of the metal partition experiments used to identify the complex protonation state, experimental conditions for the different titrations, speciation diagrams, determination of proton stoichiometry by solvent extraction, and spectroscopic data and analyses of the spectrophotometric titrations (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Cyclotron Institute, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas 77843, United States (G.A.P.)

Author Present Address

§ Eichrom Technologies, LLC, Lisle, Illinois 60532, United States (M.A.E.)

Author Contributions

This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Moyer B. A.; Lumetta G. J.; Mincher B. J.. Minor Actinide Separation in the Reprocessing of Spent Nuclear Fuels: Recent Advances in the United States. In Reprocessing and Recycling of Spent Nuclear Fuel; Elsevier Inc., 2015; 289–312. [Google Scholar]

- Widder S. Benefits and Concerns of a Closed Nuclear Fuel Cycle. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2010, 2, 062801 10.1063/1.3506839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todd T. A.; Wigeland R. A. Advanced Separation Technologies for Processing Spent Nuclear Fuel and the Potential Benefits to a Geologic Repository. ACS Symp. Ser. 2006, 933, 41–55. 10.1021/bk-2006-0933.ch003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choppin G. R. Structure and Thermodynamics of Lanthanide and Actinide Complexes in Solution. Pure Appl. Chem. 1971, 27, 23–42. 10.1351/pac197127010023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond R. M.; Street K.; Seaborg G. T. An Ion-Exchange Study of Possible Hybridized 5f Bonding in the Actinides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 1461–1469. 10.1021/ja01635a001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash K. L. The Chemistry of TALSPEAK: A Review of the Science. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2015, 33, 1–55. 10.1080/07366299.2014.985912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danesi P. R.; Cianetti C.; Horwitz E. P. Distribution Equilibria of Eu(III) in the System: Bis(2-Ethylhexyl)Phosphoric Acid, Organic Diluent—NaCl, Lactic Acid, Polyaminocarboxylic Acid, Water. Sep. Sci. Technol. 1982, 17, 507–519. 10.1080/01496398208068555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. A.; Wardle K. E.; Lumetta G.; Gelis A. V. Accomplishing Equilibrium in ALSEP: Demonstrations of Modified Process Chemistry on 3-D Printed Enhanced Annular Centrifugal Contactors. Procedia Chem. 2016, 21, 167–173. 10.1016/j.proche.2016.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelwright E. J.; Spedding F. H.; Schwarzenbach G. The Stability of the Rare Earth Complexes with Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1953, 75, 4196–4201. 10.1021/ja01113a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R. M.; Martell A. E. Critical Stability Constants, Enthalpies, and Entropies for the Formation of Metal Complexes of Aminopolycarboxylic Acids and Carboxylic Acids. Sci. Total Environ. 1987, 64, 125–147. 10.1016/0048-9697(87)90127-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver B.; Kappelmann F. A.. TALSPEAK: A New Method of Separating Americium and Curium from the Lanthanides by Extraction from an Aqueous Solution of an Aminopolyacetic Acid Complex with a Monoacidic Organophosphate or Phosphonate. 1964. RNL-3559.

- Spedding F. H.; Powell J. E.; Wheelwright E. J. The Separation of Adjacent Rare Earths with Ethylenediamine-Tetraacetic Acid by Elution from an Ion-Exchange Resin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1954, 76, 612–613. 10.1021/ja01631a091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lammers H.; Van Der Heijden A. M.; Van Bekkum H.; Geraldes C. F. G. C.; Peters J. A. Multinuclear NMR Study of the Interactions between the La(III) Complex of DTPA-Bis(Glucaminde) and Zn(II) or Borate. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1998, 268, 249–255. 10.1016/S0020-1693(97)05752-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drader J. A.; Luckey M.; Braley J. C. Thermodynamic Considerations of Covalency in Trivalent Actinide-(Poly)Aminopolycarboxylate Interactions. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2016, 34, 114–125. 10.1080/07366299.2016.1140436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braley J. C.; Carter J. C.; Sinkov S. I.; Nash K. L.; Lumetta G. J. The Role of Carboxylic Acids in TALSQuEAK Separations. J. Coord. Chem. 2012, 65, 2862–2876. 10.1080/00958972.2012.704551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lapka J. L.; Wahu S.; Sinkov S.; Nash K. L. Ternary Complex Formation and Extraction Modeling in Malonate-Buffered Trivalent Actinide-Lanthanide Separations. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 7554–7563. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.9b00808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown M. A.; Kropf A. J.; Paulenova A.; Gelis A. V. Aqueous Complexation of Citrate with Neodymium(III) and Americium(III): A Study by Potentiometry, Absorption Spectrophotometry, Microcalorimetry, and XAFS. Dalton Trans. 2014, 43, 6446–6454. 10.1039/c4dt00343h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumetta G. J.; Gelis A. V.; Carter J. C.; Niver C. M.; Smoot M. R. The Actinide-Lanthanide Separation Concept. Solvent Extr. Ion Exch. 2014, 32, 333–347. 10.1080/07366299.2014.895638. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis A. V.; Lumetta G. J. Actinide Lanthanide Separation Process - ALSEP. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 1624–1631. 10.1021/ie403569e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett C. J.; Jensen M. P. Studies of Size-Based Selectivity in Aqueous Ternary Complexes of Americium(III) or Lanthanide(III) Cations. J. Soln. Chem. 2013, 42, 2119–2136. 10.1007/s10953-013-0098-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg S. L.; Zalupski P. R.; Dutech G. Ion Interaction Models and Measurements of Eu3+ Complexation: HEDTA in Aqueous Solutions at 25 °C Containing 1:1 Na+ Salts and Citrate pH Buffer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55, 2083–2096. 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b03917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David F. Thermodynamic Properties of Lanthanide and Actinide Ions in Aqueous Solution. J. Less-Common Met. 1986, 121, 27–42. 10.1016/0022-5088(86)90511-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens E. M.; Schoene K.; Richardson F. S. Hypersensitivity in the 4f-4f Absorption Spectra of Neodymium(III) Complexes in Aqueous Solution. Inorg. Chem. 1984, 23, 1641–1648. 10.1021/ic00180a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrie D. E.; Choppin G. R. Environmental Effects on f-f Transitions. II. Hypersensitivity in Some Complexes of Trivalent Neodymium. J. Chem. Phys. 1968, 49, 477–481. 10.1063/1.1670099. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanbhag S. M.; Choppin G. R. Determination of the Stability Constant for MHL Formation by a Tracer Method. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 21, 1696–1697. 10.1021/ic00134a092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen M. P.; Chiarizia R.; Shkrob I. A.; Ulicki J. S.; Spindler B. D.; Murphy D. J.; Hossain M.; Roca-Sabio A.; Platas-Iglesias C.; de Blas A.; Rodríguez-Blas T. Aqueous Complexes for Efficient Size-Based Separation of Americium from Curium. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 6003–6012. 10.1021/ic500244p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelis A. V.; Kozak P.; Breshears A. T.; Brown M. A.; Launiere C.; Campbell E. L.; Hall G. B.; Levitskaia G.; Holfeltz V. E.; Lumetta G. J. Closing the Nuclear Fuel Cycle with a Simplified Minor Actinide Lanthanide Separation Process (ALSEP) and Additive Manufacturing. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12842. 10.1038/s41598-019-48619-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danesi P. R.; Chiarizia R.; Scibona G. The Meaning of Slope Analysis in Solvent Extraction Chemistry. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1970, 32, 2349–2355. 10.1016/0022-1902(70)80517-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alderighi L.; Gans P.; Ienco A.; Peters D.; Sabatini A.; Vacca A. Hyperquad Simulation and Speciation (HySS): A Utility Program for the Investigation of Equilibria Involving Soluble and Partially Soluble Species. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999, 184, 311–318. 10.1016/S0010-8545(98)00260-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gritmon T. F.; Goedken M. P.; Choppin G. R. The Complexation of Lanthanides by Aminocarboxylate Ligands-I. Stability Constants. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1977, 39, 2021–2023. 10.1016/0022-1902(77)80538-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyoshi A.; Ohyoshi E.; Ono H.; Yamakawa S. A Study of Citrate Complexes of Several Lanthanides. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1972, 34, 1955–1960. 10.1016/0022-1902(72)80548-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nash K. L.; Horwitz E. P. Stability Constants for Europium(III) Complexes with Substituted Methane Diphosphonic Acids in Acid Solution. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1990, 169, 245–252. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)80524-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaumot J.; de Juan A.; Tauler R. MCR-ALS GUI 2.0: New Features and Applications. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2015, 140, 1–12. 10.1016/j.chemolab.2014.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S. M. SIXpack: A Graphical User Interface for XAS Analysis Using IFEFFIT. Phys. Scr. 2005, T115, 1011–1014. 10.1238/Physica.Topical.115a01011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley F. R.; Burgess C.; Alcock R. M.. Solution Equilibria; Ellis Horwood Ltd.: Chichester, England, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Leggett D. J.SQUAD: Stability Quotients from Absorbance Data. In Computational Methods for the Determination of Formation Constants; Plenum Press: New York, 1985; 159–220. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy M. A.; Picayo G. A.; Jensen M. P.; Brown M. A.. Solvent Extraction Kinetics of Trivalent Actinide-Lanthanide Stripping by HEDTA and Citric Acid In Preparation. 2022.

- Helmholz L. The Crystal Structure of Neodymium Bromate Enneahydrate, Nd(BrO3)3·9H2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939, 61, 1544–1550. 10.1021/ja01875a062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rizkalla E. N.; Choppin G. R. Hydration of Lanthanides and Actinides in Solution. J. Alloys Compd. 1992, 180, 325–336. 10.1016/0925-8388(92)90398-S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata Y.; Yamaguchi K.; Scott Howell F. The Characterization and the Comparison of the Crystal Structures of Lanthanide Metal Complexes with N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)Ethylenediamine-N,N′ -N′-Triacetic Acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2003, 659, 61–69. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2003.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryden C. C.; Reilley C. N. Europium Luminescence Lifetimes and Spectra for Evaluation of 11 Europium Complexes as Aqueous Shift Reagents for Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 1982, 54, 610–615. 10.1021/ac00241a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choppin G. R.; Goedken M. P.; Gritmon T. F. The Complexation of Lanthanides by Aminocarboxylate Ligands-II: Thermodynamic Parameters. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1977, 39, 2025–2030. 10.1016/0022-1902(77)80539-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glentworth P.; Wiseall B.; Wright C. L.; Mahmood A. J. A Kinetic Study of Isotopic Exchange Reactions between Lanthanide Ions and Lanthanide Polyaminopolycarboxylic Acid Complex Ions-I: Isotopic Exchange Reactions of Ce(III) with Ce(HEDTA), Ce(EDTA)-, Ce(DCTA)- and Ce(DTPA)2–. J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 1968, 30, 967–986. 10.1016/0022-1902(68)80316-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brücher E.; Szarvas P. Kinetic Study of the Isotope-Exchange Reactions of the Central Ions of the Lanthanide Ethylenediaminetetraacetate and trans-1,2-Diaminocyclohexanetetraacetate Complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1970, 4, 632–636. 10.1016/S0020-1693(00)93367-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. C.; Loraas J. A. Complexes of the Rare Earths. III. Mixed Complexes with N-Hydroxyethylethylenediaminetriacetic Acid. Inorg. Chem. 1963, 2, 89–93. 10.1021/ic50005a025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choppin G. R.; Thakur P.; Mathur J. N. Complexation Thermodynamics and Structural Aspects of Actinide-Aminopolycarboxylates. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 936–947. 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S.; Limaye S.; Saxena M. Formation Constants of Lanthanide(III) - Aminopolycarboxylate - ATP Mixed Ligand Complexes and Their Systematics. Indian J. Chem. 1993, 32, 545–548. [Google Scholar]

- Martell A. E.; Smith R. M.. NIST Critically Selected Stability Constants of Metal Complexes Database, Version 8.; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Picayo G. A.; Etz B. D.; Vyas S.; Jensen M. P. Characterization of the ALSEP Process at Equilibrium: Speciation and Stoichiometry of the Extracted Complex. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 8076–8089. 10.1021/acsomega.0c00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.