Abstract

As the new representative in the carbonaceous family, carbon dots (CDs) have gained remarkable research interests over the past decade. Herein, we report the facile preparation and thorough performance comparison of three types of carbon dots with the adoption of ubiquitous natural fruit juice as precursors and demonstrate their application in pH sensing, patterning and bioimaging. All the yielded CDs show interesting optical properties including evident single- or two-photon absorption and excitation-dependent photoluminescence along with the high fluorescent yield. A detailed study on the physical properties by EPR and Stokes shift analysis and structural composition analysis by XPS and Raman spectroscopy suggest that the fluorescence of CDs originates from the electron–hole recombination via the defect state. In addition, through the regulation of non-radiative recombination rate of CDs, all the obtained CDs could be applied as fluorescent sensing platforms toward the sensitive detection of the solution pH changes by the indication of CDs' fluorescent yield and lifetime variation. Moreover, it was also proven that the resulting CDs could be employed as fluorescent inks for printing patterns in anti-counterfeit applications and as fluorescent probes for bioimaging of osteoblasts.

Carbon dots prepared with the adoption of ubiquitous natural fruit juices as precursors have good applications in pH sensing, patterning and bioimaging.

Introduction

Since the first discovery of carbon dots (CDs) by Sun et al. in 2006,1 the environmentally friendly CDs have gained great interest due to their exceptional optical/electronic properties and formidable potential application in various areas.2 Recently, several elegant strategies have been established toward preparation of high-performance CDs, such as microwave irradiation,3 ultrasonic passivation,4 arc discharge,5 hydrothermal treatment,6,7 combustion/oxidation,8–10 electrochemical exfoliation11 and laser ablation.12 Among these, hydrothermal synthesis has greatly advanced over other existing physical approaches (laser ablation or arc discharge) due to its features such as simple process, avoidance of sophisticated instrumental requirements as well as production of CDs with good fluorescence. In addition, there is an abundance of precursors can be adopted to prepare CDs. For example, CDs can be successfully prepared by the hydrothermal treatment using a vast variety of regularly consumed resources ranging from chemosynthetic polymers to low-cost or biowaste materials such as organic chemicals,13,14 gelatin,15 chitosan,16,17 fruit peels,18,19 food20–23 and drinks.24–28 The unique advantage of using precursors directly from nature make the hydrothermal treatment a more promising method for preparing CDs and would be highly beneficial for large-scale synthesis and widespread applications.

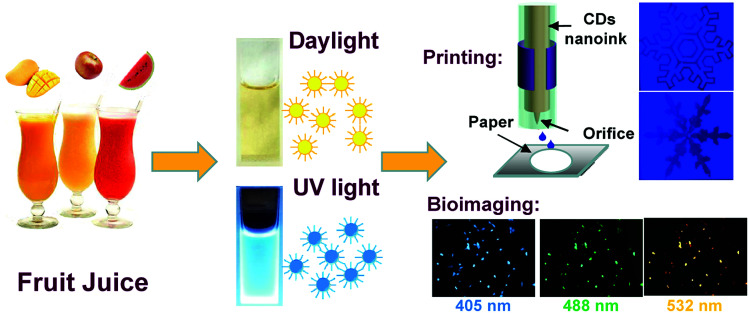

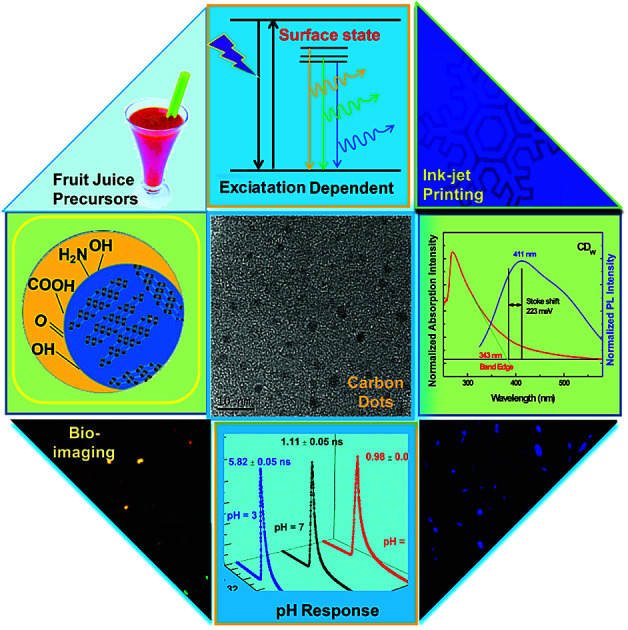

In this paper, by employing a more general and low-cost ubiquitous fruit juice as the carbon source, we developed a simple and effective route to easily prepare fluorescent CDs. The hydrothermal treatment of watermelon juice to generate fluorescent CDW at 190 °C is reported, and the thorough performance comparison of the resultant CDW with CDA and CDM (apple and mango juice as precursors) prepared under the same conditions is also presented. All the yielded CDs were found to have outstanding optical properties including the single- (CDM and CDW) and two-photon (CDA) absorption along with high quantum yields (QYs). The unique fluorescence attributed to the electron–hole recombination via the defect state of the CDs was investigated through the physical and composition analysis. In addition, the fluorescence of all the CDs exhibited quenching since it was sensitive to the solution pH variations. Moreover, the resulting CDs were employed as fluorescent inks for printing luminescent patterns on a paper substrate for anti-counterfeit applications and as fluorescent probes for bioimaging of osteoblasts (as shown in Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Preparation of fluorescent CDs from different fruit juices and their applications for printing and bioimaging.

Experimental

Materials

All the mango, apple and watermelon fruits were purchased from the local market of Jiangsu Province, China. Sodium hydroxide and nitric acid of analytical grade were purchased from the Aladdin-reagent Ltd. (Shanghai, China). High-purity water with resistivity greater than 18 MΩ cm was used for the preparation of all aqueous solutions.

Synthesis of carbon dots (CDs) from fruit juice

After peeling and removing the seeds, about 100 g of each fruit was chopped into small pieces and squeezed into liquid by adding 100 mL of highly purified water. Vacuum filtration was then performed to obtain the pulp-free juice for the hydrothermal treatment.

The resulting pulp-free juice of each fruit was transferred into a 100 mL stainless-steel autoclave, heated at a constant temperature of 190 °C for 12 h, and then cooled naturally. The obtained dark brown solution was filtered through a 0.45 μm filter to remove large particles and then washed with dichloromethane to remove unreacted organic moieties. The aqueous solution was collected and centrifuged at 15 000 rpm for 15 min to remove solid residues and further dialyzed for 30 h against highly purified water. The obtained CDs were stored away from light at 4 °C for further characterization, printing and bioimaging.

For the preparation of CDs under different pH conditions, the pH values of the pulp-free juices were first adjusted to 3, 7 and 10. Then, the same hydrothermal procedure as described above was performed to obtain the corresponding CDs.

Patterning from CD solution

For inkjet-printing, 20 mL aqueous solution of CDs was concentrated to 5 mL to form a fluorescent ink, which was encapsulated into the ink cartridge of a JetlabII Precision Printing Platform for printing at room temperature.

Cell imaging

The osteoblasts were expanded in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-low glucose (DMEM-LG, Hyclone) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The cells with a density of 4.0 × 104 cells per mL were then seeded on sterile WHB coverslips (WHB, China) on the bottom of 24-well plates, and cultured for 24 h at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 and 95% air. After the cells adhered to the coverslips, the cells were treated with the fluorescent carbon dots dissolved in fetal bovine serum-free Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium for 24 h. The cells were then washed three times with fresh phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and fixated with 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. After the cells were washed with PBS, they were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 700, Zeiss, Germany).

Characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The morphology of the CD particles was examined using a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope. A drop of the corresponding carbon dot aqueous solution was placed on a copper grid and was left to dry before transferring into the TEM sample chamber. The particle diameter was estimated using the ImageJ software analysis of the TEM micrographs.

Spectroscopy

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were recorded using a Nicolet 6700 FT-IR spectrometer. Raman study was performed using a Horiba HR 800 Raman system equipped with a 514.5 nm laser source. The elementary composition was tested using an ELEMENTRAC®CS-i elemental analyzer. The electronic structures of the samples were determined by performing X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) using a Kratos AXIS Ultra-DLD ultrahigh vacuum system (a base pressure of 3 × 10−10 torr) equipped with a monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV for XPS). UV-vis absorption spectra were recorded using a UV-vis spectrometer (Lambda 950, Perkin-Elmer). Photoluminescence measurements were performed using a Varian Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer. EPR spectra were recorded in solid state at room temperature using an EMX-10/12 spectrometer (microwave frequency: 9.751 GHz; modulation amplitude: 3.0 G; microwave power: 19.920 mW). Time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC) data were collected on an SLM 48000 spectrofluorometer using a 380 nm laser as the excitation source.

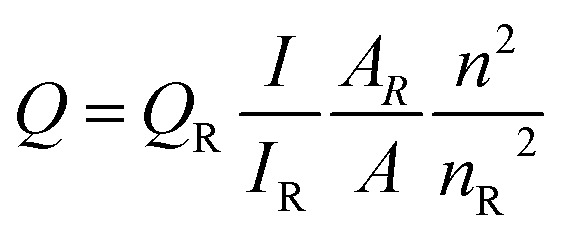

Quantum yield calculation

Quantum yield (QY) was measured according to an established procedure (J. R. Lakowicz, Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd edn, 1999, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York) using quinine sulfate in 0.10 M H2SO4 solution as the standard (Φ = 0.54). The quantum yield was calculated using the following equation: where Q is the quantum yield, I is the measured integrated emission intensity, A is the optical density and n is the refractive index (taken here as the refractive index of the respective solvents). The subscript R refers to the reference fluorophore of known quantum yield.

where Q is the quantum yield, I is the measured integrated emission intensity, A is the optical density and n is the refractive index (taken here as the refractive index of the respective solvents). The subscript R refers to the reference fluorophore of known quantum yield.

A UV-vis absorption spectrometer (Lambda 950, Perkin-Elmer) was used to determine the absorbance of the samples at 300 nm. The concentration of the samples for QY estimation should allow the first excitonic absorption peak to be below 0.05 in order to avoid any significant reabsorption. A Varian Cary Eclipse spectrophotometer with an excitation slit width of 0.25 and an emission slit width of 0.25 was used to excite the samples at 300 nm and to record their photoluminescence spectra.

Results and discussion

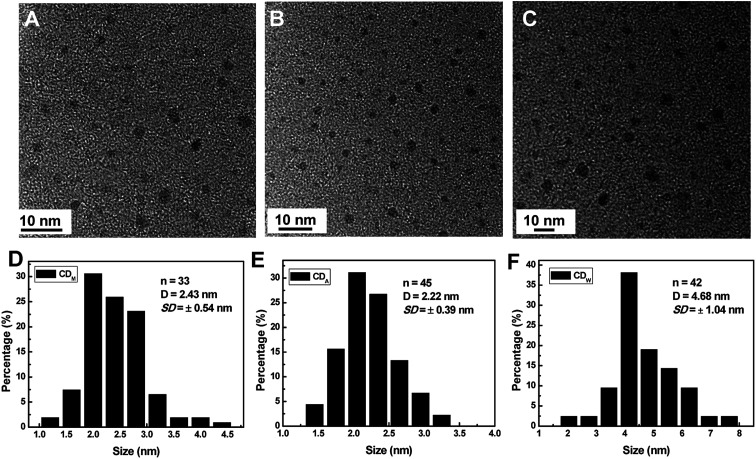

Fig. 1 displays the high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images and the size distributions of the corresponding CDs from different juices. All of the as-synthesized CDs show uniform dispersion without apparent aggregation. Through the size statistical analysis (Fig. 1D–F), the CDw particles were found to have the largest size with diameters of 4.68 ± 1.04 nm, while the CDM and CDA particles also dispersed in narrow distributions with smaller diameters of 2.43 ± 0.64 nm and 2.22 ± 0.39 nm.

Fig. 1. (A–C): HRTEM and (D–F) size histograms of CDA, CDM and CDW, respectively. The size data were derived from TEM images shown in (A–C) by self-developed digital statistic software. Number of particles counted (n), the mean particle diameter (D), along with the standard deviation (SD) are also included.

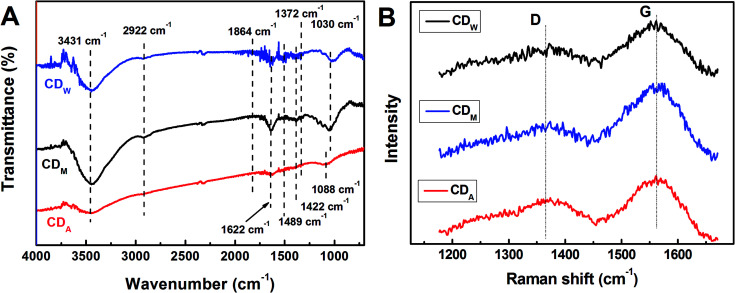

The structures of all the CDs were investigated via FT-IR analysis (Fig. 2), which indicate two peaks at 2922 cm−1 and 1372 cm−1 assigned to νas(CH3) and δs(CH3), respectively, suggesting that the surfaces of the bare CDs are attached with abundant alkyl groups. Moreover, the stretching vibrations at 1864 cm−1 and 1622 cm−1 indicate the existence of –C O in carbonyl and amide groups, respectively. The peaks at 1422 cm−1 and 1030 cm−1 in both CDM and CDW (around 1422 cm−1 and 1088 cm−1 in CDA) are assigned to asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of C–O–C group, respectively, and the peak at around 1400 cm−1 is assigned to the stretching vibration of unsaturated carbon atoms (sp2 hybridization), indicating that the as-prepared CDs contain an olefinic configuration. In addition, the broad absorption bands at around 3431 cm−1 and 1489 cm−1 are assigned to the hydroxyl group, which is associated with the molecule and in the primary alcohol group. These functional groups may confer the CDs with excellent dispersibility in aqueous solutions. The Raman spectra of these CDs (Fig. 2B) reveal two peaks at 1365 cm−1 (D band) and 1560 cm−1 (G band), revealing the presence of both sp2 and sp3 hybrid carbons.8 The calculated intensity ratios (ID/IG) are 0.84 (CDA), 0.55 (CDM) and 0.64 (CDW), indicating the high degree of graphitization of all the resultant CDs.

Fig. 2. (A) FT-IR and (B) Raman spectra of CDM, CDA and CDW, respectively.

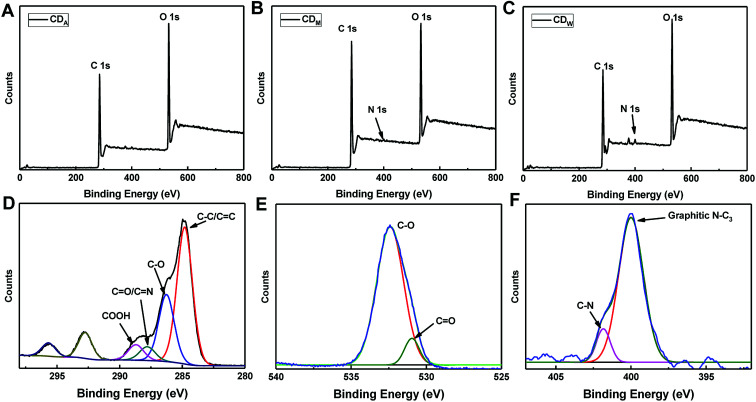

To further determine the structural compositions of the CDs, X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were recorded to identify the functional groups of the three samples. The full XPS spectra presented in Fig. 3A–C display strong signals of C 1s at 284 eV and O 1s at 531 eV as well as weak signals of N 1s at 400 eV, suggesting that all the three CDs mainly comprised C and O elements and a small amount of N element. The atomic percentages of C, N and O are displayed in Table 1. Taking CDW as an example, the deconvolution of the C 1s spectra reveals four peaks at 284.8, 286.3, 287.8 and 288.7 eV, which are assigned to C–C/C C, C–O, C O/C–N and COOH groups, respectively (Fig. 3D). The O 1s spectra (Fig. 3E) can be resolved into two components at 531.3 and 532.8 eV, associated with C O and C–O, respectively. The N band (Fig. 3F) exhibits two peaks at 399.5 and 401 eV, which are assigned to C–N and graphitic N–C3, respectively. The results from structural analysis indicated that the surface of CDs might contain carboxyl and hydroxyl groups as well as the nitrogen-containing groups including amino or amide. We also employed the elemental analyzer to test the atomic percentage inside the CDs, which revealed that the CDs are carbon (more than 60%) and oxygen-rich (more than 20%, calculated) products (Table 1). This result is consistent with XPS data and in agreement with a previous report.29 The small quantity of N and S elements contained in the as-prepared CDs may originate from the amino acid and sulphur amino acids existing in the fruit juice.

Fig. 3. XPS spectra of (A) CDA, (B) CDM and (C) CDW. (D–F) Are the C 1s, O 1s and N 1s spectra of the CDW.

Elemental analysis results of CDM, CDA and CDw, respectively.

| Sample | N (%) | C (%) | H (%) | S (%) | O (%, calculated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDA | 0.38 | 66.39 | 4.49 | 0.54 | 28.20 |

| CDM | 0.60 | 64.56 | 4.70 | 0.40 | 29.74 |

| CDW | 2.38 | 66.82 | 4.99 | 0.19 | 25.62 |

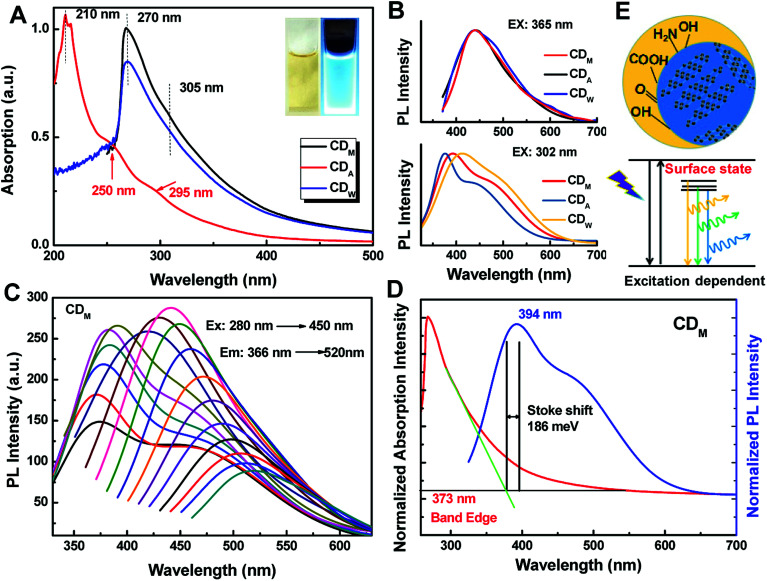

The as-prepared CDs exhibit interesting optical properties. Fig. 4A shows the UV-vis absorption spectra of the as-prepared CDs. CDM and CDW were found to have absorption at about 305 nm, which may be attributed to the π–π* transition of nanocarbon.30 More interestingly, the absorption spectrum of CDA exhibit two evident absorption peaks at 250 nm and 295 nm, confirming the π–π* and n–π* transitions, which indicates the presence of C C and C O groups in CDA.31

Fig. 4. (A) UV-vis absorption and (B) PL spectra of the as-prepared CDM, CDA and CDW aqueous solution, respectively. Insets in (A) are the photographs of CDM solution under daylight and UV lamp (365 nm). (C) PL spectra of CDM at different excitation wavelengths (in 10 nm increment starting from 280 nm to 450 nm). (D) The absorption and PL spectra of CDM solution showing the Stokes shift. (E) Schematic of excitation-dependent fluorescence emitted by CDs with various surface states.

When these CDs were excited at an excitation edge of 302 nm (Fig. 4B), it can be noticed that the photoluminescence (PL) spectra of CDs show strong emission peaks mainly centered at 393 nm (CDM), 375 nm (CDA) and 412 nm (CDW) with a shoulder. The fluorescence shoulder peaks at about 471 nm (CDM), 445 (CDM) nm and 489 nm (CDW) may evolve from the defect states of larger carbon nanoparticles. When the excitation wavelength red shifted, fluorescence originating from the larger CDs dominates (Fig. 4B). The inset photographs of Fig. 4A (and Fig. S1†) show the color of CDs under visible light (left: daylight) and fluorescence under UV illumination of 365 nm (right), which indicated that the as-prepared CDs are fluorescent in nature. The emission spectra of the as-prepared CDs also show typical excitation-dependent feature (Fig. 4C and S2†). Taking the emission spectrum of CDM for example, with gradual red shifts in the excitation wavelength from 290 nm to 450 nm, the main peak at 366 nm shifts to 450 nm gradually. As shown in Fig. 4C, CDM exhibits a maximum emission peak at 442 nm when excited at 365 nm, which results in the bright blue fluorescence of CDA. Moreover, fluorescence of the resultant CDs remained almost unchanged after three months (Fig. S3†).

It was reported that this fluorescence mechanism may be attributed to the surface defects, zigzag sites or the band gap-like transition of different functional groups on the surface of CDs.32 Herein, we noticed that this fascinating emission may be attributed to the electron–hole recombination via defect states because the Stokes shift (approximately 186 meV for CDM, 196 meV for CDA and 223 meV for CDW) is too large33 for direct excitonic recombination (Fig. 4D and S4†). In addition, the emission modes related to C–O, C O and O C–OH surface states with a series of specific energies may dominate the luminescence spectra depending on excitation energy,34 thus resulting in the excitation-dependent emission of all the CDs (Fig. 4E).

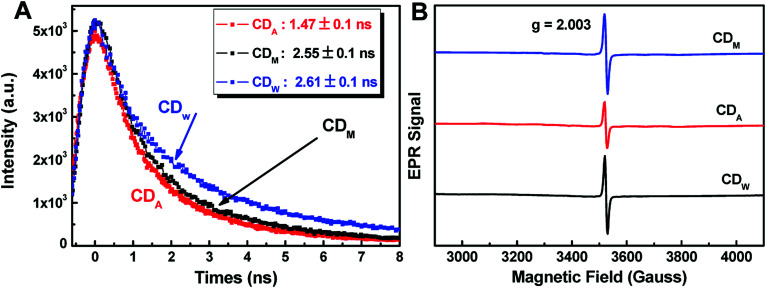

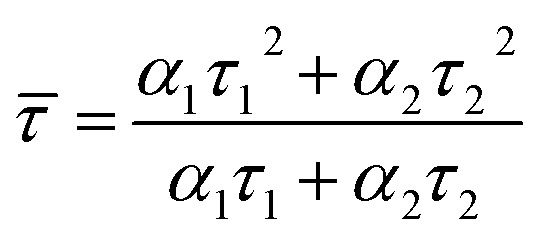

We estimated the quantum yields (QYs) of the corresponding CD aqueous solutions with quinine sulfate in 0.1 N sulfuric acid as a standard and found that the QY of CDA could be up to 7.0%, which was higher than that of CDM and CDW (5.0 and 4.9, as shown in Table 2). The QY of the resultant CDA was also higher than that of the reported CDs obtained from apple juice,25 which may be attributed to the higher temperature during the hydrothermal treatment. To further assess the stability of the as-prepared CDs, the fluorescence lifetime (τ) was determined by typical time-resolved photoluminescence measurement. As shown in Fig. 5A, the decay trace for the CDs are fitted by biexponential functions (Y(t)) based on the nonlinear least-square35 method as follows:

| Y(t) = α1 exp(−t/τ1) + α2 exp(−t/τ2) | 1 |

where α1 and α2 are the fractional contributions of time-resolved decay lifetimes of τ1 and τ2, respectively.

|

2 |

The quantum yields and the average fluorescent lifetime of the as-prepared CDs.

| Sample | CDM | CDW | CDA | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH = 3 | pH = 4.7(original) | pH = 7 | pH = 10 | |||

| QY (%) | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.3 | 7.0 | 8.1 | 15.9 |

| (ns) | 2.55 | 2.61 | 5.82 | 1.47 | 1.12 | 0.98 |

Fig. 5. (A) Time-resolved fluorescence decay curves of the as-prepared CDs solution (λex = 365 nm, λem = 442 nm). (B) The EPR spectra of CD300 powder recorded at room temperature.

According to eqn (2), the average lifetime ( ) of CDM, CDA and CDW were calculated as 2.55 ± 0.05 ns, 1.47 ± 0.05 ns and 2.61 ± 0.05 ns, respectively (χ2 < 1.1). This short lifetime of the fluorescence of these CDs is indicative of the radiative recombination of the excitons giving rise to fluorescence.30 The electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra show that all the samples have derivative EPR signal with a Lorentzian shape near g = 2.004 (Fig. 5B), revealing that the as-prepared CDs possess considerable distribution of defect sites generated by free radicals. These results together with the Stokes shift values obtained in Fig. 4D can safely conclude that the fluorescence of CDs originate from the radiative recombination of the excitons via defect states.

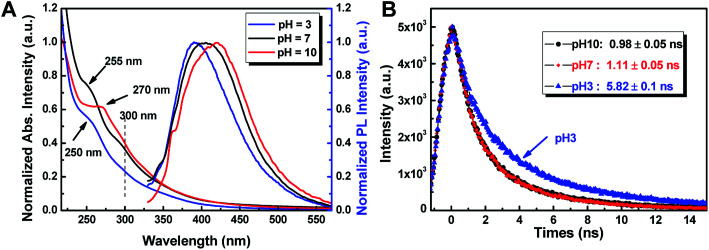

More interestingly, the optical properties of as-prepared CDs were found to be sensitive to pH. We chose CDA as an example to test its pH sensitivity. As shown in Fig. 6A, the absorption edge of CDA at 250 nm due to the π–π* transition of nanocarbon was found to gradually shift to 270 nm as the pH of the aqueous solution shifts from 3 to 10. This change in π–π* transition triggered by the concentrations of H+ and OH− may be attributed to the electronic transition in graphite nanodomains of CDs by refilling or depleting the valence bands.36 The fluorescence emission peaks of CDA red-shift from 392 nm to 405 nm and 421 nm with the pH value shifting from 3 to 7 and 10, accordingly. In addition, the QYs of CDA were found to be significantly promoted with the solution conditions changing from acid to basic. The QY could increase up to 15.9 when the pH value increases up to 10, which is almost 3 times that of the CDA prepared at pH = 3.

Fig. 6. (A) UV-vis absorption and PL spectra of CDA prepared at different pH. (B) The time-resolved fluorescence decay curves of the CDA under different pH conditions (λex = 365 nm, λem = 440 nm).

More interestingly, as shown in Fig. 6B, the lifetime of the CDA exhibits different variation trends, which gradually decreases from 5.82 ns to 0.98 ns as the pH conditions shift from 3 to 7. CDM and CDW exhibit a similar trend of fluorescent enhancement as the solution changes to alkaline. This decrease in lifetime and the significant improvement in QY may be attributed to the protective shell generated by the passivation of absorbed OH− on the original acidic defects of CD surface, which makes the CDs non-isolated and increases the non-radiative recombination rate.33,37 All of these results indicate that the as-prepared CDs are promising fluorescence-sensing platforms that are sensitive to the variations in solution pH.

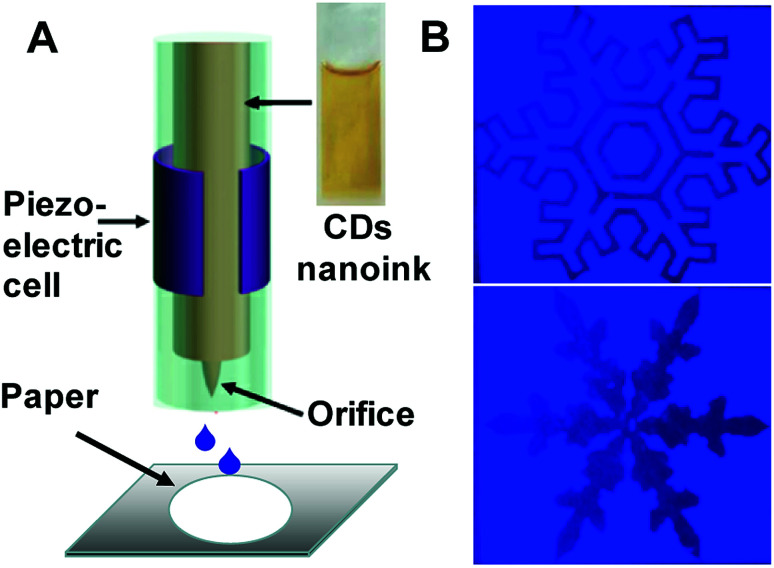

Furthermore, the as-obtained CDs were applied as fluorescent carbon inks for printing patterns. Inkjet printing has been recently proved to be a low-cost and useful technique to create high-performance flexible conductive patterns for ultraintegrated circuits, transistors, sensors or electrodes.38–41 Herein, the concentrated CDA aqueous solution as the inkjet-printing source was printed by the Jetlab@II Precision Printing Platform (Fig. 7A). The CDA solution was squeezed by the electric field to generate a pressure pulse and actuate the injected ink droplets out of the nozzle to form patterns on the paper substrate immediately. To improve the contrast of the pattern, the CDA ink was set to be sprayed on the areas out of the patterns. As shown in Fig. 7B, the patterns of different snowflakes appear dark gray under the ultraviolet light, while the surrounding CDA ink areas show bright blue fluorescence. Notably, these surrounding CD ink areas are also invisible under daylight. These properties promote the CD's applications in anti-counterfeit as well as optoelectronic fields.

Fig. 7. (A) Schematic of piezoelectric inkjet printing. Inset: the as-prepared fluorescent carbon ink. (B) Photograph of the snowflake patterns under UV light. The CDA ink is set to be printed into the surrounding to realize the clarity of the patterns.

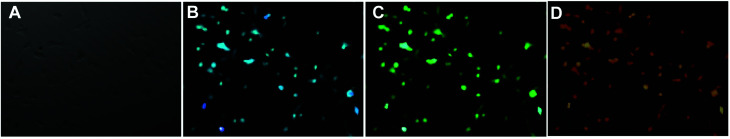

The water-soluble fluorescent carbon dots were reported to exhibit low toxicity and high stability against photobleaching.42 These unique merits along with the excellent fluorescent features make the CDs promising probes for imaging application. Herein, osteoblasts were incubated with different CDs for 24 h and then observed under a fluorescence microscope to prove the viability of CDs from fresh juices as the ideal bioimaging agent. Fig. 8 and S7† show the confocal microscopic images of osteoblasts after incubation of CDs. The strong blue, green and red fluorescence from CD-labeled cells were observed depending on the excitation wavelengths at 405 nm, 488 nm and 532 nm. In addition, no reduction in fluorescence intensity was observed after excitation for a prolonged time, which indicates that the CDs from fresh juice can serve as the ideal substitute for traditional probes in cell-imaging.

Fig. 8. (A) Osteoblasts after incubation with CDs at 37 °C for 24 h under bright field, by excitation at (B) 405 nm, (C) 488 nm and (D) 532 nm.

Conclusion

In the present study, three types of fluorescent CDs were facilely prepared via an easy one-step hydrothermal route using natural ubiquitous mango, apple and watermelon juice as precursors. All the as-prepared CDs exhibit uniform dispersion in aqueous solutions, which may be ascribed to the multifunctional hydrophilic groups on the surface of the CDs. The as-prepared CDs also show good optical properties, such as the single/two-photon absorption and the typical excitation-dependent fluorescence properties. The fascinating emission of all the CDs may be attributed to the electron–hole recombination via defect states since the Stokes shift is too large for direct excitonic recombination. Due to the increase in the non-radiative recombination rate induced by the passivation of basic groups on the original acidic defect surface, the CDs exhibit evident pH sensing properties. By adjusting the solution pH to 10, the QYs of the resultant CDs could increase up to 15.9, which is almost three times that of the CDs prepared at pH 3. Moreover, these CDs can be applied as fluorescent inks for printing various patterns, which are “vis-invisible” and “UV-visible”, promising their application in anti-counterfeit field and optoelectronic devices. The further employment of the as-prepared CDs as probes for imaging of osteoblasts indicates that the CDs from fresh juice can also serve as the ideal substitute for traditional probes in cell-imaging.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was partially funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 51702113, 61775076 and 61774070), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (Grant No. BK20150418, BK20161303 and BK20161300), Jiangsu Government Scholarship for Overseas Studies (JS-2016-019) and the Qinglan Projects of Jiangsu Province, China (2018).

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c8ra07584k

References

- Sun Y. P. Zhou B. Lin Y. Wang W. Fernando K. A. S. Pathak P. Meziani M. J. Harruff B. A. Wang X. Wang H. F. Luo P. J. G. Yang H. Kose M. E. Chen B. L. Veca L. M. Xie S. Y. Quantum-sized carbon dots for bright and colorful photoluminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7756–7757. doi: 10.1021/ja062677d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim S. Y. Shen W. Gao Z. Carbon quantum dots and their applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015;44:362–381. doi: 10.1039/C4CS00269E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J. He Y. Li S. Cui H. Amino acids as the source for producing carbon nanodots: microwave assisted one-step synthesis, intrinsic photoluminescence property and intense chemiluminescence enhancement. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:9634–9636. doi: 10.1039/C2CC34612E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. T. He X. D. Liu Y. Huang H. Lian S. Y. Lee S. T. Kang Z. H. One-step ultrasonic synthesis of water-soluble carbon nanoparticles with excellent photoluminescent properties. Carbon. 2011;49:605–609. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2010.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X. Y. Ray R. Gu Y. L. Ploehn H. J. Gearheart L. Raker K. Scrivens W. A. Electrophoretic analysis and purification of fluorescent single-walled carbon nanotube fragments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:12736–12737. doi: 10.1021/ja040082h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algarra M. Perez-Martin M. Cifuentes-Rueda M. Jimenez-Jimenez J. da Silva J. Bandosz T. J. Rodriguez-Castellon E. Navarrete J. T. L. Casado J. Carbon dots obtained using hydrothermal treatment of formaldehyde. Cell imaging in vitro. Nanoscale. 2014;6:9071–9077. doi: 10.1039/C4NR01585A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Z. B. Li Z. L. Zhang X. W. Xu G. Q. Zhou N. Fluorescent carbon dots with two absorption bands: luminescence mechanism and ion detection. J. Mater. Sci. 2018;53:6459–6470. doi: 10.1007/s10853-018-2017-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. Wang C. F. Yu Z. Y. Chen L. Chen S. Facile access to versatile fluorescent carbon dots toward light-emitting diodes. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:2692–2694. doi: 10.1039/C2CC17769B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. Wang C. F. Mao L. H. Zhang J. Yu Z. Y. Chen S. Encodable multiple-fluorescence CdTe@ carbon nanoparticles from nanocrystal/colloidal crystal guest-host ensembles. Nanotechnology. 2013;24:135602. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/24/13/135602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourlinos A. B. Stassinopoulos A. Anglos D. Zboril R. Karakassides M. Giannelis E. P. Surface functionalized carbogenic quantum dots. Small. 2008;4:455–458. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ming H. Ma Z. Liu Y. Pan K. M. Yu H. Wang F. Kang Z. H. Large scale electrochemical synthesis of high quality carbon nanodots and their photocatalytic property. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:9526–9531. doi: 10.1039/C2DT30985H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L. Wang X. Meziani M. J. Lu F. S. Wang H. F. Luo P. J. G. Lin Y. Harruff B. A. Veca L. M. Murray D. Xie S. Y. Sun Y. P. Carbon dots for multiphoton bioimaging. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11318–11319. doi: 10.1021/ja073527l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Y. Wang H. Q. Shimizu Y. Pyatenko A. Kawaguchi K. Koshizaki N. Preparation of carbon quantum dots with tunable photoluminescence by rapid laser passivation in ordinary organic solvents. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:932–934. doi: 10.1039/C0CC03552A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. C. Chang H. T. Synthesis of high-quality carbon nanodots from hydrophilic compounds: role of functional groups. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:3984–3986. doi: 10.1039/C2CC30188A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q. H. Ma W. J. Shi Y. Li Z. Yang X. M. Easy synthesis of highly fluorescent carbon quantum dots from gelatin and their luminescent properties and applications. Carbon. 2013;60:421–428. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2013.04.055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y. H. Cui J. H. Zheng M. T. Hu C. F. Tan S. Z. Xiao Y. Yang Q. Liu Y. L. One-step synthesis of amino-functionalized fluorescent carbon nanoparticles by hydrothermal carbonization of chitosan. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:380–382. doi: 10.1039/C1CC15678K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. Pang J. H. Xu F. Zhang X. M. Simple approach to synthesize amino-functionalized carbon dots by carbonization of chitosan. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31100. doi: 10.1038/srep31100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. J. Sheng Z. H. Han H. Y. Zou M. Q. Li C. X. Facile synthesis of fluorescent carbon dots using watermelon peel as a carbon source. Mater. Lett. 2012;66:222–224. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.08.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W. B. Qin X. Y. Liu S. Chang G. H. Zhang Y. W. Luo Y. L. Asiri A. M. Al-Youbi A. O. Sun X. P. Economical, green synthesis of fluorescent carbon nanoparticles and their use as probes for sensitive and selective detection of mercury(ii) ions. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:5351–5357. doi: 10.1021/ac3007939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. Bi J. R. Liu S. Wang H. T. Yu C. X. Li D. M. Zhu B. W. Tan M. Q. Presence and formation of fluorescence carbon dots in a grilled hamburger. Food Funct. 2017;8:2558–2565. doi: 10.1039/C7FO00675F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Zhang X. Zhang Y. Wang W. Li S. Y. Wang Y. C. Hu M. Y. Liu L. Bi H. Understanding the capsanthin tails in regulating the hydrophilic-lipophilic balance of carbon dots for a rapid crossing cell membrane. Langmuir. 2017;33:10259–10270. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. C. Shih Z. Y. Lee C. H. Chang H. T. Synthesis and analytical applications of photoluminescent carbon nanodots. Green Chem. 2012;14:917–920. doi: 10.1039/C2GC16451E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao S. J. Lan M. H. Zhu X. Y. Xue H. T. Ng T. W. Meng X. M. Lee C. S. Wang P. F. Zhang W. J. Green synthesis of bifunctional fluorescent carbon dots from garlic for cellular imaging and free radical scavenging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2015;7:17054–17060. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b03228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. Zhou H. S. Green synthesis of luminescent nitrogen-doped carbon dots from milk and its imaging application. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:8902–8905. doi: 10.1021/ac502646x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V. N. Jha S. Basu H. Singhal R. K. Kailasa S. K. One-step hydrothermal approach to fabricate carbon dots from apple juice for imaging of mycobacterium and fungal cells. Sens. Actuators, B. 2015;213:434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2015.02.104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu S. Behera B. Maiti T. K. Mohapatra S. Simple one-step synthesis of highly luminescent carbon dots from orange juice: application as excellent bio-imaging agents. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:8835–8837. doi: 10.1039/C2CC33796G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De B. Karak N. A green and facile approach for the synthesis of water soluble fluorescent carbon dots from banana juice. RSC Adv. 2013;3:8286–8290. doi: 10.1039/C3RA00088E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H. Ji Y. Wei J. S. Gao Q. Y. Zhou Z. Y. Xiong H. M. Facile synthesis of red-emitting carbon dots from pulp-free lemon juice for bioimaging. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2017;5:5272–5277. doi: 10.1039/C7TB01130J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X. Ji W. Q. Wang C. F. Chen S. Herbages-derived fluorescent carbon dots and CdTe/carbon ensembles for patterning. J. Mater. Sci. 2016;51:8108–8115. doi: 10.1007/s10853-016-0081-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal A. Ghosh S. S. Chattopadhyay A. One step synthesis of C-dots by microwave mediated caramelization of poly(ethylene glycol) Chem. Commun. 2012;48:407–409. doi: 10.1039/C1CC15988G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta V. N. Jha S. Singhal R. K. Kailasa S. K. Preparation of multicolor emitting carbon dots for HeLa cell imaging. New J. Chem. 2014;38:6152–6160. doi: 10.1039/C4NJ00840E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S. Song Y. Zhao X. Shao J. Zhang J. Yang B. The photoluminescence mechanism in carbon dots (graphene quantum dots, carbon nanodots, and polymer dots): current state and future perspective. Nano Res. 2015;8:355–381. doi: 10.1007/s12274-014-0644-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kong W. G. Wu H. Z. Ye Z. Y. Li R. F. Xu T. N. Zhang B. P. Optical properties of pH-sensitive carbon-dots with different modifications. J. Lumin. 2014;148:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.jlumin.2013.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X. Zhang S. Kulinich S. A. Liu Y. Zeng H. Engineering surface states of carbon dots to achieve controllable luminescence for solid-luminescent composites and sensitive Be2+ detection. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4976. doi: 10.1038/srep04976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. Wang C.-F. Chen S. Amphiphilic egg-derived carbon dots: rapid plasma fabrication, pyrolysis process, and multicolor printing patterns. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:9297–9301. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia X. Li J. Wang E. One-pot green synthesis of optically pH-sensitive carbon dots with upconversion luminescence. Nanoscale. 2012;4:5572–5575. doi: 10.1039/C2NR31319G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra S. Pathan S. H. Mitra S. Modha B. H. Goswami A. Pramanik P. Tuning of photoluminescence on different surface functionalized carbon quantum dots. RSC Adv. 2012;2:3602–3606. doi: 10.1039/C2RA00030J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan Z. Y. An J. N. Wei Y. F. Tran V. T. Du H. J. Inkjet-printed optoelectronics. Nanoscale. 2017;9:965–993. doi: 10.1039/C6NR08220C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. Feng Y. Tian Q. Yao W. Liu L. Li X. Wang H. Wu W. Tunable and ultra-stable UV light-switchable fluorescent composites for information hiding and storage. Dalton Trans. 2018;47:11264–11271. doi: 10.1039/C8DT02475H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H. Yao W. Tian Q. Li M. Tian B. Liu L. Wu Z. Wu W. Printable monodisperse all-inorganic perovskite quantum dots: synthesis and banknotes protection applications. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018 doi: 10.1002/admt.201800150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. Yao W. Liu J. Tian Q. Liu L. Ding J. Xue Q. Lu Q. Wu W. Facile synthesis and screen printing of dual-mode luminescent NaYF4:Er,Yb (Tm)/carbon dots for anti-counterfeiting applications. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2017;5:6512–6520. doi: 10.1039/C7TC01585B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi H. Wei J. Qiang L. Chen X. Meng X. Fluorescent carbon dots for bioimaging and biosensing applications. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014;10:2677–2699. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.