Abstract

Formation of methanethiol from methionine is widely believed to play a significant role in development of cheddar cheese flavor. However, the catabolism of methionine by cheese-related microorganisms has not been well characterized. Two independent methionine catabolic pathways are believed to be present in lactococci, one initiated by a lyase and the other initiated by an aminotransferase. To differentiate between these two pathways and to determine the possible distribution between the pathways, 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) performed with uniformly enriched [13C]methionine was utilized. The catabolism of methionine by whole cells and cell extracts of five strains of Lactococcus lactis was examined. Only the aminotransferase-initiated pathway was observed. The intermediate and major end products were determined to be 4-methylthio-2-oxobutyric acid and 2-hydroxyl-4-methylthiobutyric acid, respectively. Production of methanethiol was not observed in any of the 13C NMR studies. Gas chromatography was utilized to determine if the products of methionine catabolism in the aminotransferase pathway were precursors of methanethiol. The results suggest that the direct precursor of methanethiol is 4-methylthiol-2-oxobutyric acid. These results support the conclusion that an aminotransferase initiates the catabolism of methionine to methanethiol in lactococci.

The lactococci used as starter cultures in the manufacture of cheddar cheese produce metabolites that are known to be essential for cheddar cheese flavor development (16, 20). Catabolism of methionine (Met) by lactococci is of particular interest because Met is believed to be the precursor of numerous volatile sulfur compounds thought to be required for cheddar cheese flavor development (12, 24). In particular, production of methanethiol is thought to be essential for the development of typical cheddar cheese flavor (14, 15, 23, 25). Although the formation of sulfur-containing compounds in cheese resulting from the catabolism of Met has received significant attention, most studies have examined the relationship between these volatile sulfur compounds and cheese flavor. Relatively few studies have attempted to elucidate the pathways leading to the formation of these volatile sulfur compounds in cheese.

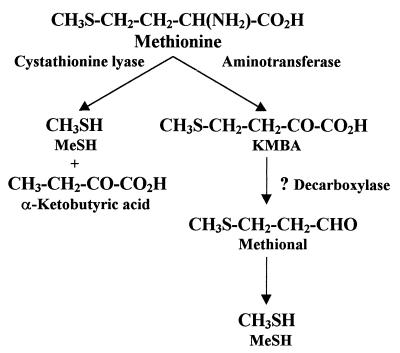

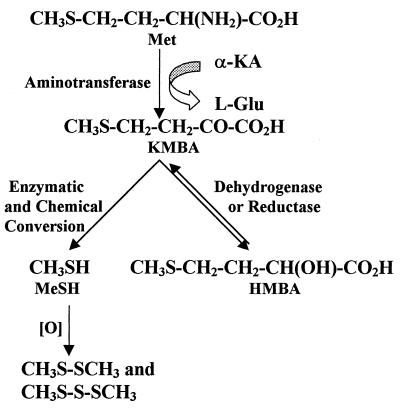

Two enzymatic pathways potentially leading to the formation of methanethiol from Met have been postulated to exist in lactococci (Fig. 1). A pathway for Met catabolism via α,γ elimination was proposed by Alting et al. (1). In this pathway, a lyase catalyzes the simultaneous deamination and demethylthiolation of Met, resulting in the formation of methanethiol and α-ketobutyric acid. Both a cystathionine β-lyase and a cystathionine γ-lyase have been purified from Lactococcus lactis and characterized (1, 3). However, both of these enzymes have relatively low activities on Met. The other potential pathway is initiated by transamination of Met to 4-methylthio-2-oxobutyric acid (KMBA). Our interest in the Met catabolic pathway was stimulated by the characterization of aromatic aminotransferases from lactococci which exhibit substantial activity with Met (10, 29).

FIG. 1.

Proposed methionine catabolic pathways in lactococci. MeSH, methanethiol.

A pathway for the conversion of Met to methanethiol initiated by an aminotransferase (Met→KMBA→3-methylthiolpropionic acid→methanethiol) has been found in a variety of mammals (2, 8, 18, 19). Two families of aminotransferases are believed to be involved in transamination of Met; the members of one family require glutamate or α-ketoglutarate (α-KA), and the other family is comprised of glutamine and asparagine aminotransferases (19, 21). Although this pathway has not been found in cheese-related microorganisms, it is possible that a similar pathway may be responsible for volatile sulfur compound production in cheddar cheese.

The catabolic pathway(s) for Met present in lactococci has not been well characterized. We utilized 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) with uniformly enriched [13C]Met to study this pathway. This approach was noninvasive and permitted unequivocal identification of metabolites throughout the pathway. To detect metabolites at micromolar concentrations, which were below the limit of detection of the 13C NMR method, gas chromatography (GC) was utilized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Uniformly enriched (97 to 98%) l-[13C]Met ([U-13C]Met) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, Mass.). Methyl 3-(methylthio)propionate, methional, and 2-ketobutyric acid were purchased from Aldrich (Milwaukee, Wis.). l-Cystathionine, l-Met, α-KA, L-arginine p-nitroaniline (Arg-pNA), 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid), and 3-methyl-2-benzothiazolone hydrazone hydrochloride were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). The aromatic aminotransferase of L. lactis S3 was purified as described by Gao and Steele (10). 3-(Methylthio)propionic acid was prepared from methyl 3-(methylthio)propionate (Aldrich Chemical Co.) as described by Steele and Benevenga (21). KMBA was either purchased from Aldrich or prepared from l-Met with amino acid oxidase as described by Dixon and Benevenga (6). 2-Hydroxyl-4-(methylthio)butyric acid (HMBA) (calcium salt) was purchased from Fluka (Ronkonkoma, N.Y.).

Bacterial strains and media.

L. lactis subsp. cremoris HP, C2, and 11007 were obtained from L. L. McKay (University of Minnesota, St. Paul). L. lactis S1 and S3 are industrial isolates. Stock cultures were maintained at −80°C, and working cultures were prepared from stock cultures by two transfers in M17 broth containing lactose (22) at 30°C.

Sample preparation for NMR experiments.

Fresh cell suspensions were prepared for each NMR experiment. Cells grown in M17 broth containing lactose for 11 to 13 h at 30°C were harvested by centrifugation, washed once with 0.85% NaCl and once with a defined medium described previously (9), and resuspended in fresh defined medium. These cells were used to inoculate (0.3 to 0.5%) the previously described lactose-limited defined medium (9), and the culture (2 liters) was incubated at 30°C for 9 to 13 h. The final optical density at 600 nm was 0.9, the pH was 5.1, the lactose was depleted, and the culture was in the stationary phase. The culture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 8 min at 4°C and washed twice with 50 mM NaH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 7.0) (unless indicated otherwise). The cell pellet was resuspended in the same buffer, and 2.8 to 3.0 ml of the cell slurry was transferred to a 10-mm NMR tube. The dry weight of the cells in the NMR tube was 0.3 to 0.4 g. The sample was then purged with helium, and 200 μl of [U-13C]Met (25 mg/ml dissolved in D2O) with or without 200 μl of 160 mM α-KA was added. The total volume of the reaction mixture was 3.2 ml, and the substrate final concentrations were each 10 mM. The NMR tube was sealed, and 7% D2O was utilized as a lock signal.

Permeabilized cells were prepared by suspending the washed cells in a solution containing 8 ml of phosphate buffer and 1 ml of toluene and shaking the preparation for 20 min with a paint can shaker (model 5410 paint mixer; Red Devil Equipment Co., Minneapolis, Minn.). After centrifugation to remove the buffer and toluene, the permeabilized cells were resuspended in fresh buffer. An analysis was performed as described above for whole cells.

Cell lysates were prepared by passing the cell suspension twice through a French pressure cell. Cell extracts (CEs) were prepared by centrifuging the cell lysates at 37,000 × g for 45 min at 4°C. The volume of cell lysate or CE used and the procedure used were the same as the volume and procedure described above for whole cells.

NMR spectroscopy.

All 13C NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker model DMX400 wide-bore NMR spectrometer operating at a carbon NMR frequency of 100.6 MHz with a broadband 10-mm-diameter NMR probe at a temperature of 30°C. The 13C NMR spectra were obtained with power-gated proton decoupling as recommended by Bruker pulse program zgpg30 by using the following parameters: 13C spectral window, 225 ppm; 90-degree pulse width, 10 μs; 1-s relaxation delay; 256 scans per spectrum; and 10 min of total acquisition time. The Met catabolic process was monitored for 18 h. The NMR spectra were referenced to external 5% 1,4-dioxane in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 5.6) with a value of 67.4 ppm. Assignments were made on the basis of 13C chemical shifts and one-bond 13C—13C coupling constants with adjacent carbon atoms.

Preparation of samples for GC.

Fresh cells of L. lactis S3 were harvested, washed once with 0.85% NaCl and twice with 66 mM KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 5.1) containing 4% NaCl, and resuspended in fresh buffer containing 4% NaCl. Part of this cell suspension was used as a source of whole cells for GC experiments. The rest was used to prepare a CE for GC experiments in which a French press was used and then the preparation was centrifuged to remove cell debris. The reactions were conducted in 17-ml screw-cap tubes. Substrates were added to a final concentration of 10 mM in a 3.2-ml reaction mixture. After the tubes were purged with helium, they were sealed with silicone septa (Supelco, Inc., Bellefonte, Pa.) held on by plastic screw caps. Holes were drilled in the caps so that there was an opening in each cap, which allowed penetration of a gas-tight syringe for headspace sampling. The tubes were incubated at 30°C for 18 h. Triplicate samples were obtained, and duplicate analyses were performed with each sample. The syringe was put in a vacuum bottle to remove the residual gases between injections.

Headspace analysis.

A headspace analysis was carried out essentially as described by Chin and Lindsay (4). Headspace gas (4 ml) was withdrawn from a tube with a 5-ml gas-tight syringe (Supelco), and samples were immediately injected into a model 3700 GC (Varian, Palo Alto, Calif.). The GC was equipped with a flame photometric detector and a Varian model 4270 integrator. The flow rates for air samples 1 and 2 and hydrogen were 80, 170, and 140 ml/min, respectively. A glass column (183 cm by 2 mm [inside diameter]) packed with 40/60 Carbopack B HT 100 (Supelco) was used to separate the volatile sulfur compounds. Helium at a flow rate of 24 ml/min was used as the carrier gas. The column temperature was first kept at 40°C for 1 min and then programmed to increase to 180°C at a rate of 20°C/min and finally kept at 180°C for 5 min. Both the injector port and detector were maintained at a temperature of 200°C. Elution times were utilized to identify compounds. Methanethiol was quantified by preparing standard curves with authentic compound. The minimum detectable concentration of methanethiol was determined to be 5 ppb.

Assays.

To measure the l-cystathionine lyase or Met lyase activity, we utilized the method described by Uren (26) for determining thiol formation and the method described by Esaki and Soda (7) for measuring α-keto acid formation. Cell autolysis during NMR experiments was evaluated by measuring intracellular aminopeptidase activity in the supernatant of the cell slurry. Aminopeptidase assays were conducted by using Arg-pNA (final concentration, 1.25 mM) as the substrate and incubating the mixtures in 80 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.1) buffer at 30°C for 30 min. Each reaction was stopped by adding 200 μl of 10% trichloroacetic acid. The absorbance at 410 nm was monitored after centrifugation.

RESULTS

Determination of methionine catabolites by 13C NMR.

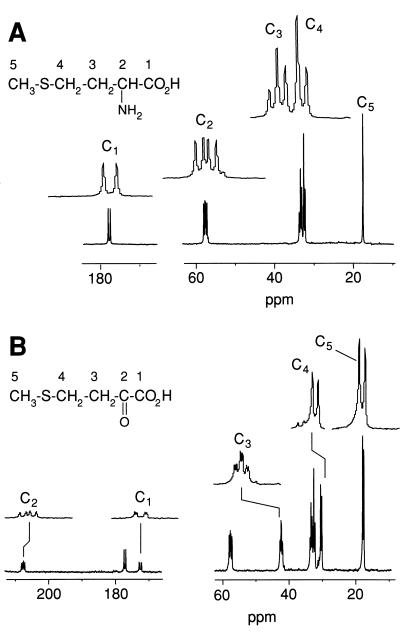

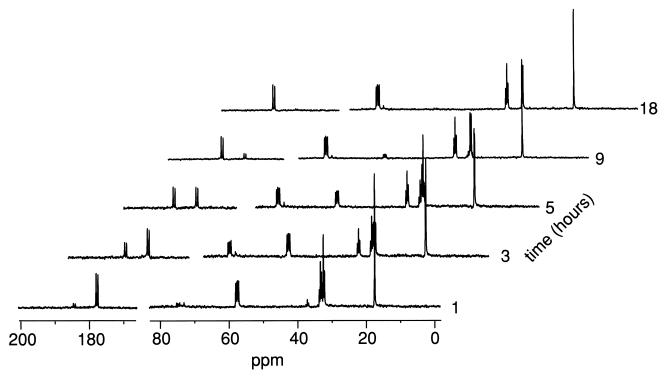

Coupling constants for adjacent 13C atoms in a uniformly enriched 13C-labeled compound and chemical shifts (Table 1) were used to determine chemical structures. Using the spectrum shown in Fig. 2A, we determined the chemical shift of each carbon and the coupling constants for adjacent carbons for the five carbons in [U-13C]Met; the results are shown in Table 2. Figure 2B shows the spectrum for a mixture of the product formed by the aromatic aminotransferase purified from L. lactis S3 with [U-13C]Met and unreacted [U-13C]Met. The peaks of the product are distinct from the peaks of [U-13C]Met. On the basis of the chemical shifts and coupling constants of the measured product (Tables 1 and 2), the product was determined to be [U-13C]KMBA. Figure 3 shows the L. lactis S3 in vivo [U-13C]Met catabolic process in the presence of α-KA at pH 7.0. Complete conversion of [U-13C]Met and accumulation of a new catabolite were observed. By analyzing coupling constants and comparing the peak chemical shifts of the new compound with the peak chemical shifts of natural HMBA (calcium salt), we determined that the final product in the spectrum was [U-13C]HMBA (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

13C chemical shifts of Met and related compounds

| Compounda | Solvent | 13C NMR data |

|---|---|---|

| l-Methionine | D2O | 15.1, 30.7, 35.1, 56.1, 183.6 |

| l-Methionineb | D2O | 15.20, 30.10, 31.00, 55.30, 175.30 |

| KMBAc | D2O | 17.11, 29.51, 41.58, 172.16, 207.42 |

| KMBAd | D2O | 15.1, 27.57, 39.61, 170.46, 205.66 |

| HMBA | D2O | 15.04, 29.65, 33.89, 70.58, 179.51 |

| 3-Methylthiopropionic acide | D2O | 16.9, 32.4, 39.6, 183.3 |

| 3-Methylthiopropionic acidd | D2O | 15.05, 29.10, 34.56, 177.5 |

| 3-(Methylthio)propionaldehyde | CDCl3 | 15.3, 26.4, 43.2, 200.7 |

| 2-Ketobutyric acid | Polysol | 6.9, 32.3, 162.6, 197.1 |

| Propionic acid | CDCl3 | 8.9, 27.7, 181.2 |

| Dimethyldisulfide | CDCl3 | 22.2 |

| Dimethylsulfide | CDCl3 | 18.0 |

| Methanethiol | CDCl3 | 6.50 |

| Formic acid | D2O | 166.3 |

FIG. 2.

Fully relaxed proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectra of [U-13C]Met (A) and the transamination reaction between [13C]Met and α-KA catalyzed by a purified aromatic aminotransferase at 30°C for 18 h (B). The enlarged peaks in panel B are KMBA peaks.

TABLE 2.

13C chemical shifts, multiplicities, and one-bond carbon-carbon coupling constants of the starting, intermediate, and final products observed in this work

| 13C NMR sample | Assignment | Measured data | Reference value (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dioxane | External reference | 67.4 ppm | 67.4 |

| l-[13C]Met | CH3S- | 14.80, s | 15.20a |

| -CH2- | 29.63, d, 1Jcc = 35 Hz | 30.10 | |

| -CH2- | 30.65, t, 1Jcc = 34 Hz, 1Jcc = 35 Hz | 31.00 | |

| -CHNH2- | 54.93, dd, 1Jcc = 33 Hz, 1Jcc = 54 Hz | 55.30 | |

| -COOH | 175.1, d, 1Jcc = 54 Hz | 175.30 | |

| KMBA | CH3S- | 15.1, s | 15.04b |

| -CH2- | 27.5, d, 1Jcc = 37 Hz | 27.57 | |

| -CH2- | 39.5, t, 1Jcc = 37 Hz, 1Jcc = 37 Hz | 39.61 | |

| -CO- | 205.7, dd, 1Jcc = 38 Hz, 1Jcc = 62 Hz | 205.66 | |

| -COOH | 170.3, d, 1Jcc = 62 Hz | 170.46 | |

| HMBA | CH3S- | 14.95, s | 15.04c |

| -CH2- | 29.85, d, 1Jcc = 36 Hz | 29.65 | |

| -CH2- | 34.46, t, 1Jcc = 36 Hz, 1Jcc = 36 Hz | 33.89 | |

| -CHOH- | 72.08, dd, 1Jcc = 36 Hz, 1Jcc = 54 Hz | 70.58 | |

| -COOH | 181.72, d, 1Jcc = 55 Hz | 179.51 |

Data from reference 27.

Data obtained from Aldrich Chemical Co. without correlation to any reference peak.

Data from the Sadtler collection.

FIG. 3.

13C NMR spectra showing the time course for consumption of [U-13C]Met by a suspension of L. lactis S3 cells in the presence of α-KA at 30°C and pH 7.0.

Catabolism of [U-13C]Met by lactococcal whole cells.

Catabolism of 10 mM [U-13C]Met in the presence of 10 mM α-KA by whole cells of five strains of lactococci was investigated by performing a 13C NMR analysis at pH 7.0 and 5.6. Four of the five strains completely converted [U-13C]Met to HMBA. KMBA, the product obtained from transamination of [U-13C]Met, was not detected under these conditions. Without α-KA, 25 to 27% of the [U-13C]Met was converted to HMBA at pH 7.0 by these four strains. No catabolism of [U-13C]Met was observed with whole cells of strain HP. After HP whole cells were permeabilized with toluene, [U-13C]Met conversion to HMBA was observed. Regardless of the lactococcal strain or cellular treatment, no α-ketobutyric acid, 3-methylthiopropionic acid, methional, methanethiol, or dimethyldisulfide was detected.

Catabolism of [U-13C]Met by lactococcal cell lysates and CEs.

Conversion of [U-13C]Met to HMBA was observed with all five cell lysates and CEs. Unlike the results obtained with whole cells or permeabilized cells, transitory accumulation followed by depletion of KMBA was observed (spectra not shown). In all cases approximately one-half of the [U-13C]Met was converted to HMBA. When α-KA was not added, no conversion of [U-13C]Met by either cell lysates or CEs was observed.

Catabolism of [U-13C]Met by lactococci under conditions which simulate Cheddar cheese ripening.

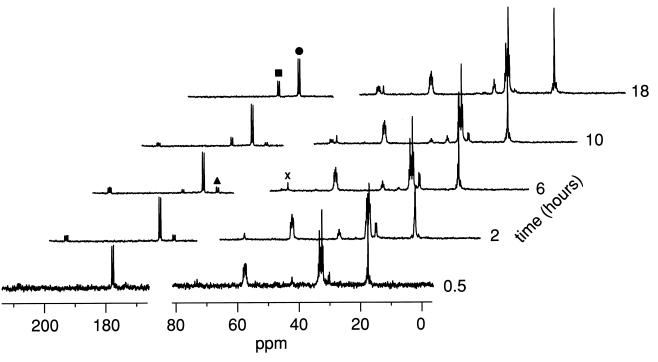

To study in vivo catabolism of [U-13C]Met by lactococci under cheeselike conditions (no carbohydrate, pH 5.1, 4% NaCl), we used a cell suspension in 66 mM KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 buffer (pH 5.1) which contained 4% NaCl. The [U-13C]Met catabolism by whole cells under cheeselike conditions is shown in Fig. 4. The results were similar to the catabolic process results obtained with cell lysates or CEs in the presence of α-KA. In both experiments, KMBA accumulated initially and HMBA accumulated as the final product. When a cell suspension was used under the cheeselike conditions without α-KA, a small amount of HMBA was detected, and approximately 13% of the total [U-13C]Met was metabolized.

FIG. 4.

13C NMR spectra showing the time course for consumption of [U-13C]Met by a suspension of L. lactis S3 cells in the presence of α-KA under cheddar cheese-like conditions (no carbohydrate, pH 5.1, 4% NaCl). The labeled peaks are peaks for C-1 of methionine (•), C-1 of KMBA (▴), C-1 of HMBA (■), and an unknown compound (×).

Analysis of volatile sulfur compounds in headspace by GC.

Methanethiol production was not observed in the NMR experiments. As methanethiol is known to have very low flavor threshold (concentration, <1 ppb), production of this compound even at a low level could have a significant impact on cheddar cheese flavor development. GC performed with a sulfur-specific detector provided a sensitive method for analyzing volatile sulfur compounds. The headspace gases of S3 whole cells incubated with Met in the presence or absence of α-KA was examined under cheeselike conditions. Three peaks were observed when the headspace gases were analyzed. Methanethiol was identified as the major product, and H2S and dimethyldisulfide were also detected. The level of dimethyldisulfide was extremely low and might have been the result of a reaction of methanethiol with residual oxygen in the system. H2S was found only in experiments performed with whole cells, and the presence of this gas was not dependent on the addition of Met. The amounts of methanethiol produced from Met, KMBA, and HMBA were determined (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Methanethiol production under cheddar cheese-like conditions (no carbohydrate, pH 5.1, 4% NaCl) after 18 h of incubation of 10 mM substrate with L. lactis S3 whole cells or CEa

| Substrate(s) | Methanethiol concn (ppb)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bufferb | Cells + buffer | CE + buffer | |

| Met | BQLc | 18 ± 2 | BQL |

| Met + α-KA | BQL | 121 ± 17 | 16 ± 4 |

| KMBA | 122 ± 1 | 562 ± 44 | 114 ± 23 |

| HMBA | BQL | 146 ± 14 | BQL |

Both whole-cell and CE samples were prepared from the same culture as described in Materials and Methods.

The buffer was 66 mM KH2PO4-Na2HPO4 containing 4% NaCl.

BQL, below quantifiable level (<5.0 ppb).

Enzymatic study.

No detectable cystathionine lyase or Met lyase activity was observed in CEs prepared from strains S1, S3, HP, and 11007. Autolysis of strain S1, S3, HP, and 11007 cells was evaluated under NMR conditions by monitoring the intracellular aminopeptidase activities in the supernatants of cell slurries and comparing these activities to the activities in CEs prepared from the cell slurries. The levels of aminopeptidase activity in the supernatants of strain S1 and S3 cell slurries were 6 and 1% of the total levels of aminopeptidase activity observed in the corresponding CEs, respectively. Aminopeptidase activity was not detected in the supernatants of strain HP or 11007 cell slurries.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that Met catabolism by lactococci is initiated mainly by an aminotransferase. The cells of four of the five lactococcal strains examined completely converted Met to HMBA in the presence of α-KA. Without α-KA, these strains only partially converted Met to HMBA, suggesting that α-KA was limiting in whole cells under the conditions used. Whole cells of HP were not capable of converting Met to KMBA or HMBA in the presence of α-KA. However, conversion of Met to HMBA was observed with permeabilized HP cells. These results suggest that HP cells lack the ability to transport free Met under these conditions. However, this probably does not affect Met catabolism by HP in cheese as peptides are believed to be the primary sources of Met in the cheese matrix (11, 13). The product of the transamination reaction, KMBA, was not observed during Met catabolism by whole cells. However, KMBA accumulated and then disappeared with cell lysates and CEs. The decrease in KMBA concentration corresponded to an increase in HMBA concentration, indicating that KMBA was converted to HMBA. One interpretation of these results is that channeling occurs in whole cells, resulting in rapid conversion of KMBA to HMBA.

In preliminary experiments, we determined that commercially available α-ketobutyric acid, a lyase pathway product, was partially decomposed into propionic acid in distilled water and buffer (data not shown). Neither α-ketobutyric acid nor propionic acid was ever detected regardless of the strain or conditions employed, suggesting that a lyase does not initiate Met catabolism in lactococci. In addition, no cystathionine lyase or Met lyase activity was detected in any of the lactococcal strains examined.

In ripening cheddar cheese, there is a lack of fermentable carbohydrate, the pH is approximately 5.1, and there is approximately 4% NaCl in the serum phase. These conditions have been shown to alter enzyme activities in lactococci (9). Therefore, to develop a better understanding of how lactococci catabolize Met under cheeselike conditions, 13C NMR studies were conducted with whole cells, Met, and α-KA under these conditions. The results indicate that KMBA accumulates and that the final product is HMBA. The absence of lyase pathway products indicates that Met catabolism occurs predominately via the transamination pathway under cheddar cheese-like conditions.

Production of methanethiol was not detected in 13C NMR experiments. To determine if this was due to the limited sensitivity of the 13C NMR procedure, a headspace GC analysis was performed. In this study we used Met and its catabolites identified by 13C NMR (KMBA and HMBA) as the substrates. The results indicate that methanethiol formation from Met occurs via an aminotransferase pathway which converts Met to KMBA, followed by either enzymatic conversion or chemical decomposition of KMBA to methanethiol. These findings suggest that accumulation of KMBA in whole cells incubated under cheeselike conditions may play a critical role in methanethiol production. The high levels of methanethiol in the headspaces of whole-cell–KMBA reaction mixtures compared to the levels of methanethiol in the buffer-KMBA reaction mixtures suggests that enzymatic conversion of KMBA to methanethiol is primarily responsible for methanethiol formation by whole cells. The observation that the levels of methanethiol produced in CE-KMBA reaction mixtures were only equal to the levels of methanethiol produced in the buffer-KMBA reaction mixtures suggests that the enzyme responsible for the conversion of KMBA to methanethiol was either inactivated or removed during preparation of the CE. It is unlikely that the cystathionine lyases that have been described previously participate in this KMBA-to-methanethiol conversion as they require a free amino group (1). However, chemical decomposition of KMBA during cheese ripening may also play an important role in methanethiol formation. The predominant product of Met catabolism, HMBA, was also converted to methanethiol, most likely after conversion to KMBA. On the basis of these results, we propose that the Met catabolic pathway shown in Fig. 5 is the primary pathway for the production of methanethiol from Met by whole lactococcal cells.

FIG. 5.

Proposed primary pathway for formation of methanethiol from methionine by lactococci. MeSH, methanethiol.

Lactococcal cell autolysis is thought to play a role in flavor development in cheddar cheese, and the balance of autolysed and intact cells is believed to be important for the desired cheese-ripening events (5, 28). The results presented here suggest that while both whole cells and cells that have undergone autolysis are capable of methanethiol formation, the two types of cells utilize different pathways. In whole cells, KMBA, produced as shown in Fig. 5, is primarily enzymatically converted to methanethiol. The release of aminotransferases from lactococci by autolysis could result in accumulation of KMBA from Met. The KMBA could then decompose to form methanethiol directly or could be converted to methanethiol enzymatically by whole cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board, and the Center for Dairy Research through funding from Dairy Management Inc. The 13C NMR analysis was conducted at the National Magnetic Resonance Facility at Madison, which is supported by NIH grant RR02301 from the Biomedical Research Technology Program, National Center for Research Resources. Equipment in the facility was purchased with funds from the University of Wisconsin, the NFS Biological Instrumentation Program (grant DMB-8415048), the NSF Academic Research Instrumentation Program (grant BIR-9214394), the NIH Biomedical Technology Program (grant RR02301), the NIH Shared Instrumentation Program (grants RR02781 and RR08438), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alting A C, Engels W M, Schalkwijk S, Exterkate F A. Purification and characterization of cystathionine β-lyase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris B78 and its possible role in flavor development in cheese. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4037–4042. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.4037-4042.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benevenga N J, Steele R D. Adverse effects of excessive consumption of amino acids. Annu Rev Nutr. 1984;4:157–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.04.070184.001105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruinenberg P G, Roo G, Limsowtin G K Y. Purification and characterization of cystathionine γ-lyase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris SK11: possible role in flavor compound formation during cheese maturation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:561–566. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.561-566.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin H-W, Lindsay R C. Volatile sulfur compounds formed in disrupted tissues of different cabbage cultivars. J Food Sci. 1993;58:835–839. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crow V L, Coolbear T, Gopal P K, Martley F G, Mckay L L, Riepe H. The role of autolysis of lactic acid bacteria in the ripening of cheese. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:855–875. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon J L, Benevenga N J. The decarboxylation of α-keto-γ-methiobutyrate in rat liver mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1980;97:930–946. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(80)91467-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esaki N, Soda K. l-Methionine γ-lyase from Pseudomonas putida and Aeromonas. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:459–465. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43081-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franken D G, Blom H J, Boers G H J, Tangerman A T, Thomas C M G, Trijbels F J M. Thiamine (vitamin B1) supplementation does not reduce fasting blood homocysteine concentration in most homozygotes for homocystinuria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1317:101–104. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(96)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao S, Oh D-H, Broadbent J R, Johnson M E, Weimer B C, Steele J L. Aromatic amino acid catabolism by lactococci. Lait. 1997;77:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao S, Steele J L. Purification and characterization of oligomeric species of an aromatic amino acid aminotransferase from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis S3. J Food Biochem. 1998;22:197–211. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juillard V, Le Bars D, Kunji E R S, Konings W N, Gripon J-C, Richard J. Oligopeptides are the main source of nitrogen for Lactococcus lactis during growth in milk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3024–3030. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3024-3030.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim S C, Olson N F. Production of methanethiol in milk fat-coated microcapsules containing Brevibacterium linens and methionine. J Dairy Res. 1989;56:799–811. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kunji E R S, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings W N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsay R C, Rippe J K. Enzymic generation of methanethiol to assist in the flavor development of Cheddar cheese and other foods. In: Parliament T H, Croteau R, editors. Biogeneration of aromas. ACS Symposium series. Vol. 317. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1986. pp. 286–308. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning D J. Sulfur compounds in relation to Cheddar cheese flavor. J Dairy Res. 1974;41:81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olson N F. The impact of lactic acid bacteria on cheese flavor. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;87:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pasini A, Perego P, Balconi M, Lupatini M. Cisplatin analogues with sulfur donor ligands. (Ethylenediamine)platinum(II) complexes with ligands possessing a sulfinyl or sulfanyl group linked to an anionic oxygen donor atom. Reactivity and cytotoxicity. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 1995;1995:579–585. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scislowski P W D, Bremer J, Thienen W I A D, Davis E J. Heart mitochondria metabolize 3-methylthiopropionate to CO2 and methanethiol. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1989;273:602–605. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90521-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scislowski P W D, Pickard K. Methionine transamination-metabolic function and subcellular compartmentation. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;129:39–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00926574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steele J L. Contribution of lactic acid bacteria to cheese ripening. In: Malin E L, Tunick M H, editors. Chemistry of structure-function relationships in cheese. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steele R D, Benevenga N J. Identification of 3-methylthiopropionic acid as an intermediate in mammalian methionine metabolism in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:7844–7850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Urbach G. Relations between cheese flavor and chemical composition. Int Dairy J. 1993;3:389–422. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urbach G. Contribution of lactic acid bacteria to flavor compound formation in dairy products. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:877–903. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Urbach G. The flavor of milk and dairy products: II. Cheese: contribution of volatile compounds. Int J Dairy Technol. 1997;50:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uren J R. Cystathionine β-lyase from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1987;143:483–486. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)43086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voelter W, Jung G, Breitmaier E, Bayer E. 13C-NMR chemical shifts of amino acids and peptides. Z Naturforsch. 1971;26B:213–222. doi: 10.1515/znb-1971-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson M G, Guinee T P, O’Callaghan D M, Fox P F. Autolysis and proteolysis in different strains of starter bacteria during Cheddar cheese ripening. J Dairy Res. 1994;61:249–262. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yvon M, Thirouin S, Rijnen L, Fromentier D, Gripon J G. An aminotransferase from Lactococcus lactis initiates conversion of amino acids to cheese flavor compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:414–419. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.414-419.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]