Abstract

The findings of this study demonstrate that Vibrio vulnificus isolates recovered from diseased eels in Denmark are heterogeneous as shown by O serovars, capsule types, ribotyping, phage typing, and plasmid profiling. The study includes 85 V. vulnificus isolates isolated from the gills, intestinal contents, mucus, spleen, and kidneys of eels during five disease outbreaks on two Danish eel farms from 1995 to 1997, along with a collection of 12 V. vulnificus reference strains. The results showed that more than one serovar may be capable of causing disease in eels and that these isolates are genetically heterogenous as shown by ribotyping. Ribotyping also showed that the same isolates may persist in an eel farm and cause recurrent outbreaks. Phage typing did not correlate with ribotyping or serotyping. However, we observed that 26 of 28 isolates, which were not susceptible to any of the phages, showed the same ribotype, O serovar, and capsule type. This suggests that these isolates may possess features that make them resistant to lysis by the phages used in this study. Ninety-three of 97 isolates harbored between one and three high-molecular-weight plasmids which previously had been suggested to be associated with eel virulence. The subdivision of V. vulnificus into two biotypes based on the indole reaction can no longer be supported, since 82 of 97 isolates in this study were indole positive, and a subdivision into serovars appears to be more correct.

Vibrio vulnificus is a gram-negative marine bacterium with strains grouped into two biotypes defined by host range and phenotypic characteristics (38). V. vulnificus biotype 1 is ubiquitous in estuarine environments and is an opportunistic human pathogen capable of causing fatal septicemia and severe wound infections (17, 19, 25, 32). Biotype 2 is typically recovered from diseased eels but is also reported to cause illness in humans after handling of eels (6, 19, 28). This biotype was also isolated from brackish water and sediment in Denmark (25).

The first isolates of V. vulnificus biotype 2 were isolated from Japanese eels (Anguilla japonica) between 1975 and 1977 (30, 31). V. vulnificus biotype 2 was first observed in Europe in 1989, when recurrent outbreaks occurred in cultured Anguilla anguilla in Spain (12). V. vulnificus biotype 2 was isolated from wound infections in humans in Denmark first in 1991 and again in 1994 (6, 19, 24). The association between V. vulnificus and diseased eels was first recognized in Denmark in 1995, as described in the present study. The majority of eel farms in Denmark use freshwater to culture eels. A few land-based eel farms, however, use brackish water, which is a natural reservoir for both biotypes (25).

V. vulnificus strains of both biotypes share many phenotypic properties, virulence factors, production of exotoxins, iron uptake systems, and the ability to produce capsule (3, 4, 11, 14, 15). Bisoca et al. (13) proposed to rename those strains previously classified as biotype 2 to serovar E based on three criteria: (i) serovar E strains express a homogeneous lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-based O serogroup, while biotype 1 strains are serologically heterogenous; (ii) the majority of serovar E strains are indole negative, and the majority of biotype 1 strains are indole positive; and (iii) only serovar E strains are virulent for eels. V. vulnificus biotype 2 strains are also genetically homogenous compared to biotype 1 strains, and they also harbor high-molecular-weight plasmids, which may be associated with virulence (7, 15, 16).

Expression of capsular material by V. vulnificus biotype 2 is not essential for development of vibriosis in eels when the V. vulnificus is introduced by intraperitonal injection (15). The capsule, however, is necessary for waterborne infection and may facilitate initial adherence to eel mucus or gills (2). Once encapsulated cells have invaded the eel, they must survive the bactericidal actions of the host immune system. The O side chain of serovar E LPS protects V. vulnificus biotype 2 cells against the cidal action of serum complement, whereas biotype 1 strains are readily killed by eel serum (5).

In the present study we present data from five outbreaks of V. vulnificus which occurred on two Danish eel farms with brackish water intake. A serotyping scheme which included 10 capsular types and 5 O serovars, not previously tested on biotype 2 strains, was used to serologically characterize these isolates (27, 36). A newly described phage typing system, based on lysis patterns produced by 13 V. vulnificus-specific bacteriophages isolated from U.S. Gulf Coast oysters, was also used to further characterize the isolates in combination with genotypic characterization (21). The findings reported reveal that vibriosis outbreaks on Danish eel farms are caused by heterogenous isolates of V. vulnificus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of V. vulnificus.

The 85 V. vulnificus isolates examined in this study were collected as part of diagnostic work done during five disease outbreaks on two eel farms (designated A and B) from 1995 to 1997 (Table 1). Both eel farms use brackish water to culture eels, and they are separated by approximately 60 km of coastline. The water temperature and salinity in the farms are maintained at 24°C and 0.9%, respectively, to provide optimal growth conditions.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of 85 V. vulnificus isolates isolated from diseased eel tissues during five outbreaks on two Danish eel farms

| Outbreak, eel farm, and yr | No. of isolates | Source(s) | Indole reaction | O serovar | Capsule type | Ribotype | Phage type | Plasmid profile (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, A, 1995 | 4 | Mucus, intestines, kidney | + | O3 | NTa | 1 | 1 | 3.9, 39, 52, 68 |

| 4 | Mucus, gills, kidney | + | O3 | NT | 1 | 2 | 3.9, 52, 68 | |

| 8 | Gills, intestines, kidney | + | O3 | NT | 1 | 2 | 3.9, 39, 52, 68 | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | O3 | NT | 1 | 3 | 3.9, 52, 68 | |

| 1 | Mucus | − | NT | NT | 2 | 4b | —c | |

| 1 | Kidney | + | O3 | NT | 1 | 5 | 3.9, 52, 68 | |

| 2, B, 1995 | 15 | Mucus, gills, intestines | + | O3/O4d | NT | 1 | 1 | 3.9, 37, 52, 68 |

| 3 | Mucus, intestines | + | O3/O4 | NT | 1 | 1 | 3.9, 37, 52, 68 | |

| 1 | Gills | + | O3/O4 | NT | 1 | 5 | 3.9, 52, 68 | |

| 1 | Gills | + | O3/O4 | NT | 1 | 6 | 3.9, 37, 52, 68 | |

| 3, B, 1996 | 12 | Mucus, gills, intestines, kidney, spleen | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 40, 63, 105 |

| 4, B, 1996 | 5 | Mucus, gills, intestines | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 40, 63, 105 |

| 1 | Gills | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 105 | |

| 2 | Gills | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 63, 105 | |

| 1 | Mucus | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 7 | 63 | |

| 1 | Intestine | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 40, 63, 105 | |

| 1 | Mucus | + | NT | 9 | 4 | 2 | 135 | |

| 1 | Mucus | + | NT | NT | 4 | 1 | 135 | |

| 5 | Mucus, gills, intestines, spleen | + | NT | NT | 4 | 2 | 135 | |

| 2 | Mucus, intestines | + | NT | NT | 4 | 2 | 105 | |

| 1 | Mucus | + | NT | NT | 4 | 8 | 105, 135 | |

| 5, B, 1997 | 5 | Mucus, gills, intestines | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 63 |

| 1 | Mucus | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 105 | |

| 2 | Mucus | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 63 | |

| 1 | Gills | + | O4 | 9 | 3 | 12 | 63 | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | NT | 9 | 4 | 10 | 94 | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | NT | NT | 4 | 10 | 94 | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | NT | NT | 4 | 11 | 132 | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | NT | NT | 4 | 13 | — | |

| 1 | Intestines | + | NT | NT | 4 | 17 | 94 |

NT, not typeable.

Isolates with phage type 4 are not lysed by any of the 13 phages.

—, no plasmids.

Strong positive reaction with O3 antiserum (1.200 ≤ A405 ≤ 1.400) and weak positive reaction with O4 antiserum (0.200 < A405 ≤ 0.300).

The mucus from each eel (A. anguilla) was scraped off with a sterile blunt knife. The skin covering the gills was removed, and approximately three gill arches from each eel were sampled with sterile scissors and forceps. An incision was made from the rectum towards the head of the eel, and 2 to 3 cm of the intestines was sampled with sterile scissors and forceps. Approximately 1 g each of mucus, gills, and intestinal contents was inoculated into 10 ml of alkaline peptone water and incubated for 6 to 8 h at 37°C (22). The turbid alkaline peptone water was streaked onto modified cellobiose-colistin-polymyxin B plates and incubated at 40°C for 18 to 24 h (22). Tissue aliquots were taken aseptically from both the kidney and spleen with an inoculating loop and streaked directly onto blood agar (BA) plates (Blood Agar base [Difco; Detroit, Mich.] supplemented with 5% citrated calf blood). The BA plates were incubated at 20°C for 48 to 96 h. Two colonies with typical V. vulnificus morphology (flat, yellow colonies approximately 2 mm in diameter) were picked from each modified cellobiose-colistin-polymyxin B plate and each BA plate and identified by colony hybridization with a V. vulnificus-specific alkaline phosphatase-labeled DNA probe (DNA Technology, Aarhus, Denmark) directed against the cytolysin gene as previously described (25, 29). One isolate from each of the tissues removed from each individual eel was included in the study. Forty-nine eels were necropsied.

Reference strains.

The reference strain V. vulnificus biotype 2 (ATCC 33149) and 11 V. vulnificus strains isolated from diseased eels in Spain, Norway, and Sweden were included in the present study (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of V. vulnificus biotype 2 strains recovered from diseased eels

| Isolate | Country | Indole reaction | O serovar | Capsule type | Ribotype | Phage type | Plasmid profile (kb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 33149 | Japan | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 16 | 56, 67 |

| E22a | Spain | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | NDb | 56, 67 |

| 91-5-96 | Sweden | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 16 | 51, 71 |

| 90-2-11c | Norway | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 56, 71 |

| 938d | Norway | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 56, 71 |

| 910527-1/1e | Sweden | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 48, 67 |

| 910905-1/1e | Sweden | − | NTf | NT | 5 | 15 | 2.5, 7.1, 67 |

| 910905-1/2e | Sweden | − | O3 | NT | 5 | 2 | 2.5, 7.1, 67 |

| 910905-1/3e | Sweden | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 1 | —g |

| 940309-1/1e | Sweden | − | NT | 2 | 6 | 14 | <2.1,h 2.6, 2.9, 46, 63, 120 |

| 940309-1/2e | Sweden | − | O4 | NT | 7 | 4 | 2.5, 2.6, 2.9, 3.4, 46, 63, 120 |

| 940309-1/3e | Sweden | − | O4 | 9 | 3 | 7 | — |

Received from E. G. Biosca, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain.

ND, not done.

Received from E. Myhr, National Veterinary Institute, Olso, Norway.

From Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge.

Received from U. Johansson, The National Veterinary Institute, Uppsala, Sweden.

NT, nontypeable.

—, no plasmids.

The plasmid was smaller than the 2.1-bp marker band.

Indole production.

Each V. vulnificus isolate was tested for indole production following 48 h of incubation at 37°C in tryptone broth (1% tryptone [Difco], 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.5) with Kovács reagent (9).

Whole-cell ELISA.

Five LPS-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) reagents designated O1 to O5 were used in the whole-cell enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) format (27). The V. vulnificus isolates tested by ELISA were grown in heart infusion broth (Difco) for 24 h at 37°C and then diluted with an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.5), which gives 3 × 109 CFU/ml. A 50-μl aliquot of the diluted cell suspension was added to each of 16 flat-bottomed wells of protein-binding polystyrene (Immunlon 1; Dynatech Laboratories, Inc., Alexandria, Va.), and cells were dried overnight at 37°C. The ELISA with anti-LPS MAb was done as previously described (27). The A405 for each well was read after 15 min of incubation with substrate in a microwell strip reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, Vt.). A well was considered positive if its A405 reading was 0.200 above that of the negative control. Serovar O3 in the present study corresponds to the serovar O1 described earlier (27). The O5 MAb has been described earlier, whereas the MAbs to serovars O1, O2, and O4 in this study have not been (27).

Coagglutination of V. vulnificus with anticapsule MAbs.

Polyclonal rabbit anticapsule sera were fixed to formalin-killed Staphylococcus aureus Cowan I ATCC 12598 cells (35). A single opaque colony of the V. vulnificus isolates was grown in heart infusion broth for 24 h at 30°C and tested directly by coagglutination. Capsule purification methods, conjugation of capsule to protein carriers, and rabbit immunization protocols were described earlier (36). Ten anticapsule sera were used, and each isolate in the present study was tested against each of these 10 antisera. The three capsule types described earlier, representing V. vulnificus C7184, 1007, and 938, have the designations capsule types 1, 4, and 9, respectively, in the present study (36).

LPS extraction.

LPS was extracted from selected V. vulnificus isolates by a modification of the procedure of Valverde et al. (39), which does not require cell lysis. Cells from each isolate tested were grown on heart infusion agar (Difco) at 37°C for 24 h, and 200 mg of cells was harvested and transferred to an Eppendorf tube. The cells were mixed with 500 μl of 100 mM EDTA which had been titrated with triethylamine to pH 7.0. The cells were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 30 s and incubated for 35 min at room temperature. The EDTA-triethylamine cell suspension was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant fluid was transferred to clean Eppendorf tubes. Next, 300 μl of a polymyxin B resin suspension (Affi-Prep Polymyxin; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.) was added to each tube and incubated at room temperature for 15 min on a rotary shaker (100 rpm), and the cells were sedimented at 10,000 × g for 2 min. The supernatant fluid was discarded, and the pellet was washed one time in 1 ml of buffer (100 mM KH2PO4, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7), resuspended in 500 μl of sterile distilled water, and placed in a 100°C water bath for 5 min. Heat treatment releases LPS from the polymyxin B resin. The heated suspension was centrifuged for 2 min at 10,000 × g to sediment the polymyxin B resin. The supernatant fluid, which contained the extracted LPS, was used as an antigen in an LPS ELISA format.

LPS ELISA.

The LPS ELISA was done in the same manner as described for the whole-cell ELISA except that polyvinyl chloride microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories, Inc.) were coated with 50 μl of undiluted LPS and 50 μl of four twofold dilutions. The plates were dried overnight at 37°C. The A405 for each well was read at 5 min after addition of the substrate with a microwell strip reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc.). A well was considered positive if its A405 reading was 0.200 above that of the negative control.

Ribotyping.

Chromosomal DNA was extracted by the method of Pedersen and Larsen (34) and digested with the restriction enzyme HindIII. Electrophoresis conditions, blotting procedures, hybridization with a dioxigenin-labeled cDNA probe complementary to 16S and 23S rRNAs of Escherichia coli at 56°C, and detection procedures were performed as described previously (18). A 1-kb DNA ladder (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) was used as a molecular size marker. Ribotype patterns were considered to be different when there was a difference of one band between the isolates. Each ribotype was designated with an arbitrary number.

Phage typing.

A quantitative direct plating method was used to isolate phages from oysters collected in Louisiana, Alabama, and Florida. All reagents were prepared as described previously (20). Each candidate phage was screened for host specificity, and ultimately 13 phages which produced unique lysis patterns were used in this study.

Each V. vulnificus isolate tested was grown to log phase and then plated on Casamino Acids-Peptone marine medium (5 g of Casamino Acids [Difco], 5.0 g of Bacto Peptone [Difco], 1.0 liter of seawater, 1.5% Bacto Agar [Difco]) by the soft agar overlay technique (21). After 1 h, the plates were spotted with 4 μl from each phage stock and then incubated overnight at 26°C. Bacterial isolates were considered susceptible to phage infection when they produced either clear or turbid plaques.

Plasmid screening.

Each V. vulnificus isolate examined for plasmids was grown in Luria broth (Difco) supplemented with 2% NaCl at 37°C for 18 to 24 h. Plasmid DNA was isolated by methods described by Olsen, which included incubation at an elevated pH of 12.45 for 30 min at 56°C during the lysis step (33). Plasmid DNA was electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose gels (SeaKem GTG, FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine), and the gels were stained with ethidium bromide and photographed under UV light. Plasmids in the same size range were electrophoresed in the same gel. Plasmids extracted from E. coli V517 and 39R861 were used as molecular size markers. V. vulnificus plasmid sizes were estimated by their relative migrations compared to the migrations of plasmids of known sizes from E. coli V517 and 39R861.

RESULTS

Eel farm A.

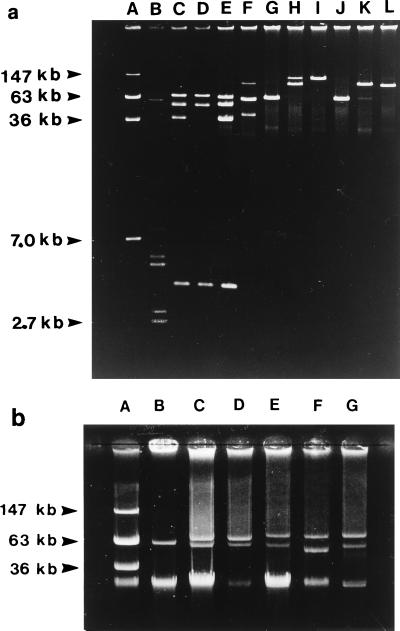

Table 1 shows that V. vulnificus isolates recovered from the single outbreak of vibriosis on farm A were quite homogenous. Eighteen of 19 isolates tested were indole positive, expressed the O3 serovar, and belonged to ribotype 1 (Fig. 1). None of these isolates was agglutinated with any of the 10 capsule antisera. While 12 of 19 isolates were phage type 2, the remaining seven isolates were type 1, 3, 4, or 5 (Tables 1 and 3). Two different plasmid profiles were observed among these isolates, with four plasmid sizes which ranged from 3.9 to 68 kb (Table 1; Fig. 2). There was a good correlation between ribotype and O serovar among these 19 isolates, but there was little agreement between these two features and phage type or plasmid profile. Each of these 19 V. vulnificus isolates was recovered from dead eels which showed heavy infestations with the parasite Pseudodactylogyrus sp.

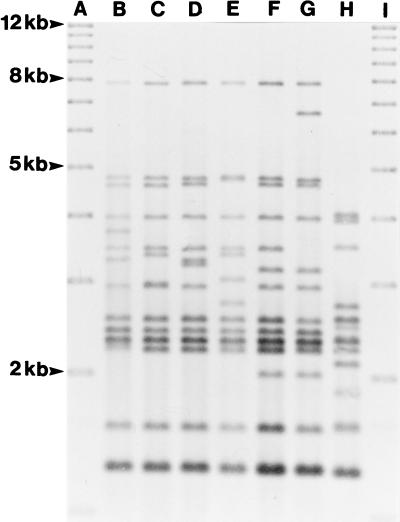

FIG. 1.

Seven ribotypes shown by 97 V. vulnificus isolates from diseased eels in Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Japan. Lanes A and I, 1-kb ladder; lane B, ribotype 3; lane C, ribotype 5; lane D, ribotype 6; lane E, ribotype 7; lane F, ribotype 1; lane G, ribotype 4; lane H, ribotype 2.

TABLE 3.

Phage types observed in the present study

| Phage type | Lysis by phage no. (phage strain designation):

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (152A-2) | 2 (152A-6) | 3 (152A-8) | 4 (152A-9) | 5 (152A-10) | 6 (154A-8) | 7 (154A-9) | 8 (153A-5) | 9 (153A-7) | 10 (153A-8) | 11 (108A-9) | 12a (110A-7) | 13a (7-8) | |

| 1 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 2 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + |

| 3 | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 4 | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 5 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 7 | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 8 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| 9 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| 10 | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| 11 | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 12 | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| 13 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 14 | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + |

| 15 | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 16 | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | + | + |

| 17 | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + |

Phage strain described previously.

FIG. 2.

(a). Representative plasmid profiles shown by V. vulnificus isolates recovered from diseased Danish eels. Lanes A and B, E. coli V517 and 39R861, respectively; lanes C and D, isolates from outbreak 1; lane E, isolate from outbreak 2; lane F, isolate from outbreak 3; lanes G, H, and I, isolate from outbreak 4; lanes J, K, and L, isolates from outbreak 5. (b) Representative plasmid profiles shown by V. vulnificus biotype 2 strains from diseased eels. Lanes A and B, E. coli V517 and 39R861, respectively; lane C, E22; lane D, ATCC 33149; lane E, 90-2-11; lane F, 91-5-96; lane G, LSU 938.

Eel farm B.

Vibriosis outbreaks 2, 3, 4, and 5 occurred on farm B (Table 1). Outbreak 2 occurred 2 weeks following outbreak 1 at farm A. Antibiotic treatment (oxolinic acid) had been initiated before diseased eels were examined. The V. vulnificus isolates from outbreak 2 were recovered from both the external surface and intestinal contents of each diseased eel but not from internal organs.

The isolates from outbreaks 1 and 2 were indole positive, were ribotype 1, exhibited a capsule type of unknown type, and were serovar O3 (1.200 ≤ A405 ≤ 1.400). The isolates from farm B also showed a weak positive reaction (0.200 < A405 ≤ 0.300) with the O4 MAb. Phage type 1 was the dominant phage type and differs by only one lysis reaction from phage type 2, which was dominant on farm A. Plasmids of similar molecular sizes were detected in the isolates from farms A and B in 1995 (Table 1; Fig. 2).

Both high mortality rates and septicemia were observed during outbreak 3 in 1996 on farm B. Twelve V. vulnificus isolates were recovered from both external and internal tissues of each eel. There was 100% agreement between each pair of parameters tested. Each isolate was serovar O4, capsule type 9, ribotype 3, and resistant to lysis by all phages, and they harbored three high-molecular-weight plasmids.

Three months later, outbreak 4 occurred, and V. vulnificus was isolated from the external mucus, gills, intestines, and spleen but not from the kidneys. Five of the 20 isolates were identical to types seen in outbreak 3. Another five isolates differed from the first five isolates only in phage type and plasmid profile. The remaining 10 isolates were heterogenous (Table 1).

During outbreak 5, V. vulnificus was isolated from the external surface and the intestinal contents only. The eel pathogen Pseudomonas anguilliseptica was prevalent in each internal organ. Nine of 14 V. vulnificus isolates were serovar O4, expressed capsule type 9, and were also ribotype 3, whereas the indole reaction, phage type, and plasmid profile varied. The remaining five isolates were ribotype 4 and were of unknown O and capsule types, characteristics which were prevalent in V. vulnificus isolated the previous year. Thirteen of 14 organisms harbored a single high-molecular-weight plasmid which varied in size (63 to 132 kb) (Table 1; Fig. 2).

LPS ELISA.

LPS was extracted from a representative isolate from each of the five outbreaks and was used as antigen in the ELISA. The agreement between the results of the LPS ELISA and the results of the whole-cell ELISA was 100% (data not shown). The weak A405 readings observed with the O4 MAb for isolates tested from outbreak 2 (farm B) were confirmed. Undiluted LPS extracted from each representative isolate from outbreak 2 showed a strong positive reaction with the O3 MAb (A405 > 2.999) and a weak positive reaction with the O4 MAb (A405 = 0.282). These findings confirmed that positive reactions seen in the whole-cell ELISA were the result of the MAb binding to the LPS O side chain.

Reference strains.

Eight of the 12 reference strains, including the biotype 2 reference strain ATCC 33149, were indole negative, serovar O4, capsule type 9, and ribotype 3 (Table 2). These same eight strains were of four phage types and showed plaques with 2 to 8 of the 13 phages. Six of these eight strains had almost identical plasmid profiles, with two high-molecular-weight plasmids ranging from 48 to 56 and from 67 to 71 kb. The reference strain ATCC 33149 harbored two plasmids and not three plasmids as reported earlier (13).

DISCUSSION

V. vulnificus isolates recovered from diseased eels on Danish eel farms were found to be heterogenous when examined by five different criteria: indole reaction, O and capsule serologies, ribotype, and phage type. Division of V. vulnificus into two biotypes based on the indole reaction can not be defended; we support the suggestion to classify V. vulnificus strains into O-antigen serovars. This study suggests that more than one serovar may be capable of causing disease in eels.

In outbreak 1 (serovar O3), a heavy infestation with the parasite Pseudodactylogyrus sp. may have predisposed eels to a secondary infection with V. vulnificus serovar O3. The isolates isolated in this outbreak were not as heterogenous as typical environmental isolates (24). This suggests that V. vulnificus was responsible for this disease outbreak. In outbreak 2 (serovar O3/O4), antibiotic treatment had been initiated before the eels were examined bacteriologically, and this may explain why V. vulnificus was not isolated from internal organs. Investigations to determine if O3 and O3/O4 serovars are pathogenic to eels are in progress.

The O side chain component of the LPS in serovar E strains has been shown to protect this serovar from the bactericidal action of serum complement, whereas biotype 1 (non-serovar E) strains are killed promptly by nonimmune eel serum (5). Our results suggest that several LPS-associated serovars (O3, O3/O4, and O4) may cause disease in eels. The results do not agree with the current proposal that V. vulnificus biotype 2 constitutes a homogenous O serogroup (13). The biotype 2 reference strain ATCC 33149 and the Spanish strain E22, which has been reported previously to belong to serovar E (13), were found to be serovar O4 in this study. This indicates that our designation serovar O4 corresponds to serovar E. Currently V. vulnificus biotype 2 strains are serotyped with a single polyclonal rabbit antiserum and not with MAbs, while five monoclonal reagents were employed in the present study. Polyclonal antisera may lack the serological specificity to reveal the existence of several serovars which are pathogenic for eels. Atypical serovar E strains have been described (13), which may indicate that there are additional eel-pathogenic O groups not included in the current serovar E group. The use of MAb typing reagents will improve the serological characterization of V. vulnificus strains to an extent that the use of polyclonal antiserum cannot accomplish.

The production of capsule in V. vulnificus biotype 1 strains confers resistance to the bactericidal effect of human serum and phagocytosis (26, 37). Several specific types of capsular polysaccharides in V. vulnificus biotype 1 strains have been described, but the number of different capsule types among biotype 2 strains has not been investigated (23, 36). The capsule in biotype 2 strains has been suggested to favor adherence to eel mucus and to be essential for virulence in natural conditions (2). We found that all isolates that could be agglutinated by any of the 10 capsular antisera were capsule type 9, except for a single isolate that belonged to capsule type 2. Capsule type 9 was detected in 39 of 40 isolates belonging to the O4 serovar. This suggests a linkage between the expression of this particular O antigen and capsule type. The isolates from outbreak 2, which had a weak positive reaction with the O4 antiserum as well as a strong positive reaction with the O3 antiserum, did not belong to any known capsule type. Further, two isolates had capsule type 9 without belonging to the O4 serovar. Our results indicate that at least several capsules types are found among eel-pathogenic V. vulnificus isolates and that capsule type 9 may increase virulence.

Thirty-eight of 39 isolates isolated from diseased eels from farms A and B within a 2-week period in 1995 showed an identical ribotype (1) and belonged to the O3 and O3/O4 serovars, respectively (Table 1). The ribotyping results indicate that eel-pathogenic V. vulnificus isolates may be capable of spreading over long distances (60 km of coastline) or simply that isolates with that particular ribotype were present throughout the marine environment in 1995. Since the isolates from farms A and B have an identical ribotype, there is reason to speculate that the O3/O4 serovar may have evolved from the O3 serovar or that both serovars may have evolved from a common ancestor. It could be speculated that the serotype is influenced by phage or plasmid conversion, since no chromosomal change was observed (same ribotype) and the plasmid profiles and phage types differ somewhat for the O3 and O3/O4 serovars.

A single indole-negative isolate isolated in 1995 showed a different ribotype (2), which differed by several bands from the other ribotypes observed (Fig. 1). This isolate did not belong to the O3 serovar as did the remaining isolates in that outbreak, suggesting that it might be a single environmental isolate not associated with the disease outbreak.

In eel farm B the same two ribotypes were seen during three outbreaks in 1996 and 1997, which suggests that V. vulnificus may have persisted in the farm between outbreaks and infected the eels when they were otherwise stressed, e.g., by infection with another eel-pathogenic bacterium as described for outbreak 5. One of these ribotypes (ribotype 3) corresponds to the HindIII ribotype shown to be dominant among serovar E strains (13).

Interestingly, two strains from diseased eels from Sweden showed ribotype 5, which has been associated with wound infections in humans in Denmark during the summer of 1995 (19). This finding supports the suggestion that V. vulnificus biotype 2 should be considered an opportunistic human pathogen (1, 24).

Ribotype patterns correlated with both O serovars and capsule types. All 39 isolates belonging to both serovar O4 and capsule type 9 showed ribotype 3 (Tables 1 and 2). Further, 39 of 40 isolates giving strong positive reactions with the O3 antiserum belonged to the same ribotype (ribotype 1) (Tables 1 and 2). Ribotyping has been described as being able to distinguish between biotype 1 and 2 strains (7, 8, 24). However, our results indicate that no ribotype is unique to eel-pathogenic isolates and that isolates from diseased eels are more genotypically heterogenous than described in the literature (7, 8, 13).

Most phages cannot infect cells that are fully encapsulated or contain well-expressed O side chains of LPS, but some bacteriophages attach specifically to capsules or O side chains (10). This study does not find that any of the 13 phages attach to certain types of LPS or capsules. The majority of V. vulnificus isolates (68 of 96 isolates) in this study were lysed by one or more of the V. vulnificus-specific phages isolated from Gulf of Mexico oysters. This suggests a relatedness among V. vulnificus isolates worldwide. Between one and six phage types were seen in each outbreak (Table 1). Phage types 1, 2, and 4 were observed within several different ribotypes and O serovars, suggesting that there is no obvious correlation between phage typing, ribotyping, and serotyping (Tables 1 and 2). Of the 28 isolates that were not susceptible to any of the 13 phages, 26 showed the same ribotype, O serovar, and capsule type (ribotype 3, serovar O4, and capsule type 9) (Tables 1 and 2). This observation indicates that these isolates possess features that make them resistant to lysis by the phages used in this study. Nine isolates with the same characteristics (ribotype 3, serovar O4, and capsule type 9), however, were lysed by phages, which suggests that neither the LPS type O4 nor the capsule type 9 protects against phage infection.

A relationship between high-molecular-weight plasmids and virulence in eels has been suggested by Biosca et al., who found that a plasmid-free serovar E strain had a significantly higher 50% lethal dose in eels than serovar E strains harboring high-molecular-weight plasmids (13). Our data suggest that high-molecular-weight plasmids may be associated with virulence in eels, because 93 of 97 isolates in this study harbored one to three high-molecular-weight plasmids of various sizes.

The indole reaction has previously been suggested to be the only biochemical test that can distinguish between V. vulnificus biotypes 1 and 2 (16). One biotype 2 strain has previously been reported to be indole positive, and our data further demonstrate that indole production is not a reliable marker for biotype 2, since the majority of isolates (82 of 97) in this study were indole positive (13). All 12 reference strains were indole negative. This suggests that eel-pathogenic V. vulnificus isolates, which are indole positive, are unique to Danish eel farms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work received financial support from The Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries and The Danish Environmental Protection Agency, Ministry of Environment and Energy. Preparation of serological agents was supported by the Louisiana Sea Grant College Program, a part of the National College Program maintained by NOAA, U.S. Department of Commerce. Lise Høi was supported by a fellowship from The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University.

The technical assistance of Anita Forslund, Kirsten Kaas, and Anne-Mette Petersen is highly appreciated.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaro C, Biosca E G. Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2, pathogenic for eels, is also an opportunistic pathogen for humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1454–1457. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.4.1454-1457.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaro C, Biosca E G, Fouz B, Alcaide E, Esteve C. Evidence that water transmits Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 infections to eels. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1133–1137. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.1133-1137.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amaro C, Biosca E G, Fouz B, Toranzo A E, Garay E. Role of iron, capsule, and toxins in the pathogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 for mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:759–763. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.759-763.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amaro C, Biosca E H, Esteve C, Fouz B, Toranzo A E. Comparative study of phenotypic and virulence properties in Vibrio vulnificus biotypes 1 and 2 obtained from a European eel farm experiencing mortalities. Dis Aquat Org. 1992;13:29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amaro C, Fouz B, Biosca E G, Marco-Noales E, Collado R. The lipopolysaccharide O side chain of Vibrio vulnificus serogroup E is a virulence determinant for eels. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2475–2479. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2475-2479.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersen H K. Vibrio vulnificus. J Danish Med Assoc. 1991;153:2361–2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arias C R, Verdonck L, Swings J, Garay E, Aznar R. Intraspecific differentiation of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes by amplified fragment length polymorphism and ribotyping. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2600–2606. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2600-2606.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aznar R, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Ribotyping and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1993;16:303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrow G I, Feltham R K A, editors. Cowan and Steel’s manual for the identification of medical bacteria. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayer M E, Bayer M H. Biophysical and structural aspects of the bacterial capsule. ASM News. 1994;60:192–198. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biosca E G, Amaro C. Toxic and enzymatic activities of Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 with respect to host specificity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2331–2337. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.7.2331-2337.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biosca E G, Amaro C, Esteve C, Fouz B, Toranzo A E. First record of Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 from diseased European eels, Anguilla anguilla L. J Fish Dis. 1991;14:103–109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biosca E G, Amaro C, Larsen J L, Pedersen K. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of Vibrio vulnificus: proposal for the substitution of the subspecific taxon biotype for serovar. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1460–1466. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1460-1466.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biosca E G, Fouz B, Alcaide E, Amaro C. Siderophore-mediated iron acquisition mechanisms in Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:928–935. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.928-935.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Biosca E G, Llorens H, Garay E, Amaro C. Presence of a capsule in Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2 and its relationship to virulence for eels. Infect Immun. 1993;61:1611–1618. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.1611-1618.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biosca E G, Oliver J D, Amaro C. Phenotypic characterization of Vibrio vulnificus biotype 2, a lipopolysaccharide-based homogenous O serogroup within Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:918–927. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.918-927.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blake P A, Merson M H, Weaver R E, Hollis D G, Heublein P C. Disease caused by a marine vibrio. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197901043000101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalsgaard A, Echeverria P, Larsen J L, Siebeling R J, Serichantalergs O, Huss H H. Application of ribotyping for differentiating Vibrio cholerae non-O1 isolates from shrimp farms in Thailand. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:245–251. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.245-251.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dalsgaard A, Frimodt-Møller N, Bruun B, Høi L, Larsen J L. Clinical manifestations and epidemiology of Vibrio vulnificus infections in Denmark. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1996;15:227–231. doi: 10.1007/BF01591359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePaola A, Mcleroy S, Mcmanus G. Distribution of Vibrio vulnificus phage in oyster tissue and other estuarine habitats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2464–2467. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2464-2467.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DePaola A, Motes M L, Chan A M, Suttle C A. Phages infecting Vibrio vulnificus are abundant and diverse in oysters (Crassostrea virginica) collected from the Gulf of Mexico. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:346–351. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.346-351.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elliot E L, Kaysner C A, Jackson L, et al. Bacteriological analytical manual. 9th ed. Arlington, Va: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 1995. Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus, and other Vibrio spp; pp. 9.01–9.27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayat U, Reddy G P, Bush C A, Johnson J A, Wright A C, Morris J G. Capsular types of Vibrio vulnificus: an analysis of strains from clinical and environmental sources. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:758–762. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Høi L, Dalsgaard A, Larsen J L, Warner J M, Oliver J D. Comparison of ribotyping and randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR for characterization of Vibrio vulnificus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1674–1678. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1674-1678.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Høi L, Larsen J L, Dalsgaard I, Dalsgaard A. Occurrence of Vibrio vulnificus biotypes in Danish marine environments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:7–13. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.1.7-13.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kreger A, DeChatelet L, Shirley P. Interaction of Vibrio vulnificus with human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: association of virulence with resistance to phagocytosis. J Infect Dis. 1981;144:244–248. doi: 10.1093/infdis/144.3.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martin S J, Siebeling R J. Identification of Vibrio vulnificus O serovars with antilipopolysaccharide monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:1684–1688. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.8.1684-1688.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mertens A, Nagler J, Hansen W, Gepts-Friedenreich E. Halophilic, lactose-positive Vibrio in a case of fatal septicemia. J Clin Microbiol. 1979;9:233–235. doi: 10.1128/jcm.9.2.233-235.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morris J G, Wright A C, Roberts D M, Wood P K, Simpson L M, Oliver J D. Identification of environmental Vibrio vulnificus isolates with a DNA probe for the cytotoxin-hemolysin gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:193–195. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.1.193-195.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muroga K, Jo Y, Nishibuchi M. Pathogenic Vibrio isolated from cultured eels. I. characteristics and taxonomic status. Fish Pathol. 1976;11:141–145. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nishibuchi M, Muroga K, Jo M. Pathogenic Vibrio isolated from cultured eels. V. Serological studies. Fish Pathol. 1980;14:117–124. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oliver J D. Vibrio vulnificus. In: Doyle M P, editor. Foodborne bacterial pathogens. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. pp. 569–600. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olsen J E. An improved method for rapid isolation of plasmid DNA from wild-type gram-negative bacteria for plasmid restriction profile analysis. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;10:209–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765x.1990.tb01335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen K, Larsen J L. rRNA gene restriction patterns of Vibrio anguillarum serogroup O1. Dis Aquat Org. 1993;16:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simonson J, Siebeling R J. Rapid serological identification of Vibrio vulnificus by anti-H coagglutination. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;52:1299–1304. doi: 10.1128/aem.52.6.1299-1304.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simonson J G, Siebeling R J. Immunogenicity of Vibrio vulnificus capsular polysaccharides and polysaccharide-protein conjugates. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2053–2058. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2053-2058.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamplin M L, Specter S, Rodrick G E, Friedman H. Vibrio vulnificus resists phagocytosis in the absence of serum opsonins. Infect Immun. 1985;49:715–718. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.3.715-718.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tison D L, Nishibuchi M, Greenwood J D, Seidler R J. Vibrio vulnificus biogroup 2, a new biogroup pathogenic for eels. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:640–646. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.3.640-646.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valverde C, Hozbor D F, Lagares A. Rapid preparation of affinity-purified lipopolysaccharide samples for electrophoretic analysis. BioTechniques. 1997;22:230–236. doi: 10.2144/97222bm07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]