Abstract

Mosquito vectors are a tremendous public health threat. One in six diseases worldwide is vector-borne transmitted mainly by mosquitoes. In the last couple of years, there have been active Yellow fever virus (YFV) outbreaks in many settings in Nigeria, and nationwide, entomological surveillance has been a significant effort geared towards understanding these outbreaks. In this study, we used a metagenomic sequencing approach to characterize viruses present in vector samples collected during various outbreaks of Yellow fever (YF) in Nigeria between 2017 and 2020. Mosquito samples were grouped into pools of 1 to 50 mosquitoes, each based on species, sex and location. Twenty-five pools of Aedes spp and one pool of Anopheles spp collected from nine states were sequenced and metagenomic analysis was carried out. We identified a wide diversity of viruses belonging to various families in this sample set. Seven different viruses detected included: Fako virus, Phasi Charoen-like virus, Verdadero virus, Chaq like-virus, Aedes aegypti totivirus, cell fusing agent virus and Tesano Aedes virus. Although there are no reports of these viruses being pathogenic, they are an understudied group in the same families and closely related to known pathogenic arboviruses. Our study highlights the power of next generation sequencing in identifying Insect specific viruses (ISVs), and provide insight into mosquito vectors virome in Nigeria.

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Molecular biology

Introduction

One in six diseases worldwide is transmitted by mosquito vectors1. It is estimated that half of the world's population is in danger of viral illnesses spread by mosquitoes and causing death in millions of people annually. Rift Valley fever virus (RVF), Dengue virus (DENV), Zika virus (ZIKV), Chikungunya virus (CHIKV), Yellow fever virus (YFV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), and Ross River virus (RRV) are just a few of the mosquito-borne viruses that have caused disease epidemics both in humans and animals. Additionally, an increasing number of viruses specific to arthropods, classified as insect-specific viruses (ISVs), have been identified in the last two decades in diverse mosquito populations around the world2–8. ISVs and pathogenic arboviruses evolutionary relationship remains uncertain9. However, evolution from arthropod-specific viruses has been assumed for the genus Flavivirus. Pathogenic viruses are thought to have evolved from insect-specific to dual host viruses10–12.

Metagenomic sequencing has increased exponentially the number of mosquito-borne viruses isolated in the last couple of years and further provided fresh insight into the enormous complexity and variety of invertebrate RNA viruses4,6,11. Recently, in Nigeria, metagenomic sequencing was used to identify an ongoing yellow fever outbreak and its aetiology and inform real-time public health actions, resulting in accurate and timely disease management and control13. A greater understanding of the virome in mosquito species in Nigeria could allow for a more accurate assessment of mosquito-borne disease risk, vector competence and mosquito management.

In the course of various YFV outbreaks in Nigeria between 2017 and 2020, we collected vector samples (mostly Aedes spp) in sites where there were active YFV cases. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) was carried out on 26 pools of 1300 mosquitoes (50 mosquitoes per pool) across nine (9) states in Nigeria using a metagenomic protocol as previously described14. In this paper we present our findings and discuss the implications.

Results

Metagenomics analysis

Metagenomics analysis carried out on sequenced samples revealed the presence of a wide range of viruses (Fig. 1). The following Families of viruses; Bunyavirales (Phasi Charoen-like phasivirus), Iflaviridae (Tesano Aedes virus), Partitiviridae (Chaq-like virus and Verdadero virus), Flaviviridae (Cell fusing agent virus) and Totiviridae (Aedes aegypti totivirus (AaTV) were detected.

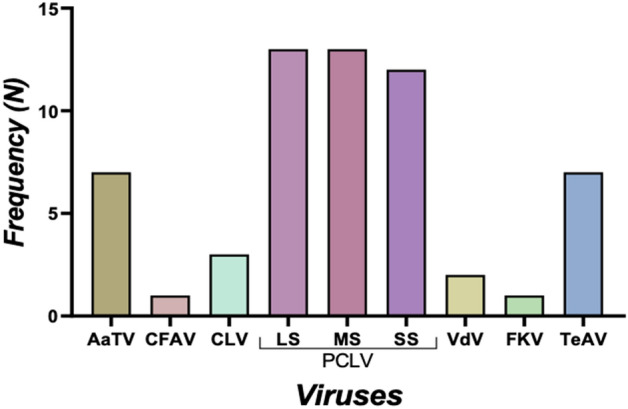

Figure 1.

Frequency distribution of the viruses found in the mosquito pools. AaTV Aedes aegypti totivirus, CFAV cell fusing agent virus, CLV Chaq-like virus, PCLV Phasi Charoen-like phasivirus (L segment, M segment, and S segment), VdV Verdadero virus, FKV Fako virus, TeAV Tesano Aedes virus.

The mosquito species that were pooled after morphological identification included the following: Aedes aegypti (n = 12 pools), Aedes albopictus (n = 10 pools), Aedes simpsoni complex (n = 2) Aedes luteocephalus and Anopheles coustani (n = 1 pool each) with Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus accounting for more than 80% of the mosquito pools analyzed. Of the 26 pools, irrespective of the mosquito species, the number of pools positive for Aedes aegypti totivirus (AaTV), cell fusing agent virus (CFAV), Chaq like-virus (CLV), Phasi Charoen like phasivirus (PCLV) (L segment), PCLV (M segment), PCLV (S segment), Verdadero virus (VdV), Fako virus (FKV) and Tesano Aedes virus (TeAV), were 7, 1, 3, 13, 13, 12, 2, 1 and 7 respectively (Fig. 1).

The prevalence of PCLV was significantly higher compared to other viruses (P < 0.0001). Table 1 shows the distribution of the virus in the mosquito pools. The distributions were estimated as the proportion of the positive pool over the total pool analyzed for each pathogen. It is an expression used to indicate the proportion/ratio/frequency in various cohorts in a population. Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus were the most common mosquitoes in the study areas. They accounted for > 80% of the pools analyzed in the study. In addition, no viral genome was assembled from Aedes simpsoni, Aedes simpsoni complex and Anopheles coustani pools. Excluding these minor groups of the mosquito pools, distributions of the viruses between the two major species were similar. In Aedes aegypti: Excluding CFAV from statistical comparison, the prevalence of PCLV was significantly higher compared with other viruses (P = 0.006; Table 1). In Aedes albopictus: Excluding FKV and TeAV from statistical comparison, the prevalence of the viruses was similar (P = 0.41; Table 1). FKV and TeAV were excluded because the proportions were zero, and there will be no meaningful statistical comparison with zero value (e.g. 0 of 10).

Table 1.

Distribution of the viruses based on the species of mosquitoes.

| Mosquito species | Viruses | P value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AaTV | CFAV | CLV | PCLVLS | PCLVMS | PCLVSS | VdV | FKV | TeAV | ||

| Aedes aegypti | 4/12 | 0/12 | 2/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 9/12 | 0/12 | 2/12 | 1/12 | 0.003* |

| Aedes albopictus | 3/10 | 1/10 | 1/10 | 4/10 | 4/10 | 3/10 | 2/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0.41** |

| Aedes luteocephalus | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | – |

| Aedes simpsoni C | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | 0/2 | – |

| Anopheles coustani | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | 0/1 | – |

AaTV Aedes aegypti totivirus, CFV cell fusing agent virus, CLV Chaq-like virus, PCLP Phasi Charoen like phasivirus (L segment, M segment, and S segment), VdV Verdadero virus, FV Fako virus, TeAV Tesano Aedes virus, C complex.

*CFAV was excluded from this analysis.

**FKV and TeAV were excluded from this analysis.

Genome assembly and phylogenetic analysis

Genome assembly of viruses detected by our metagenomics pipeline15 was attempted to characterize the diversity of these viruses and their evolutionary relationship with previously reported viruses. A heatmap showing the distribution of viruses is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

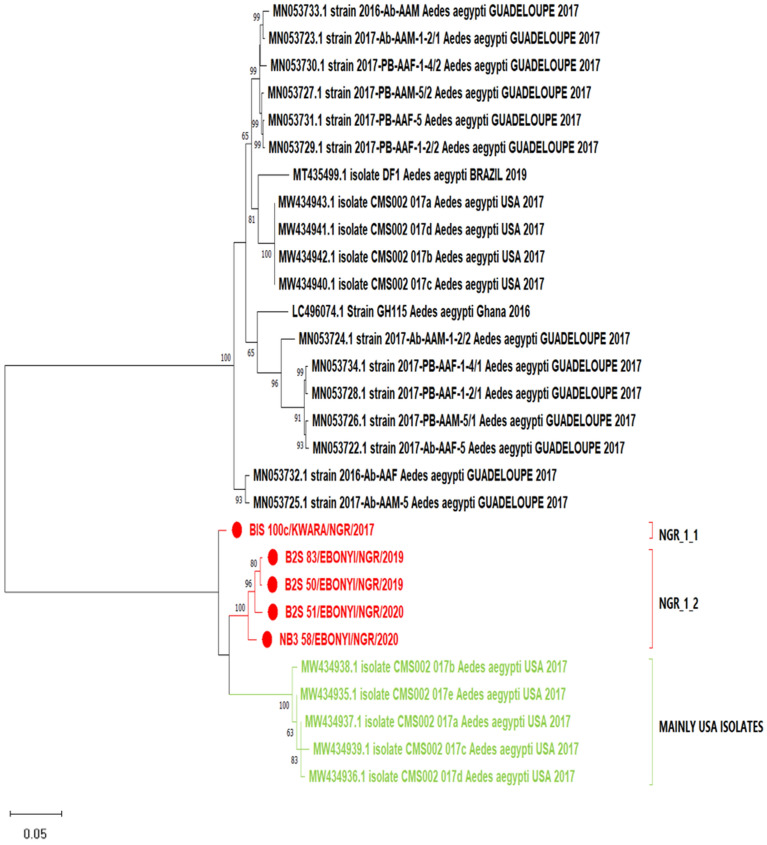

Totiviridae

We assembled six (five full and one partial) genomes for Aedes aegypti totivirus (AaTV) out of the seven pools with reads for this virus. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that the Aedes aegypti totivirus sequences from this study clustered closely together and fell in the same major clade. Within the major clade, the sequence from Kwara state (BIS 100c) branched out on its own while the Ebonyi sequences (NB3 58, B2S 51, B2S 50 and B2S 83) clustered together, which could imply a localized/within-state spread of the virus. The short branch lengths of the sequences also show the limited diversity of the virus in Nigeria (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of orf1 nucleotide sequences of Aedes aegypti totivirus (AaTV). The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers at branch nodes indicate the bootstrap values ≥ 50%. All the reference strains are identified by name and GenBank accession number. Virus strains characterized in this study are highlighted in red.

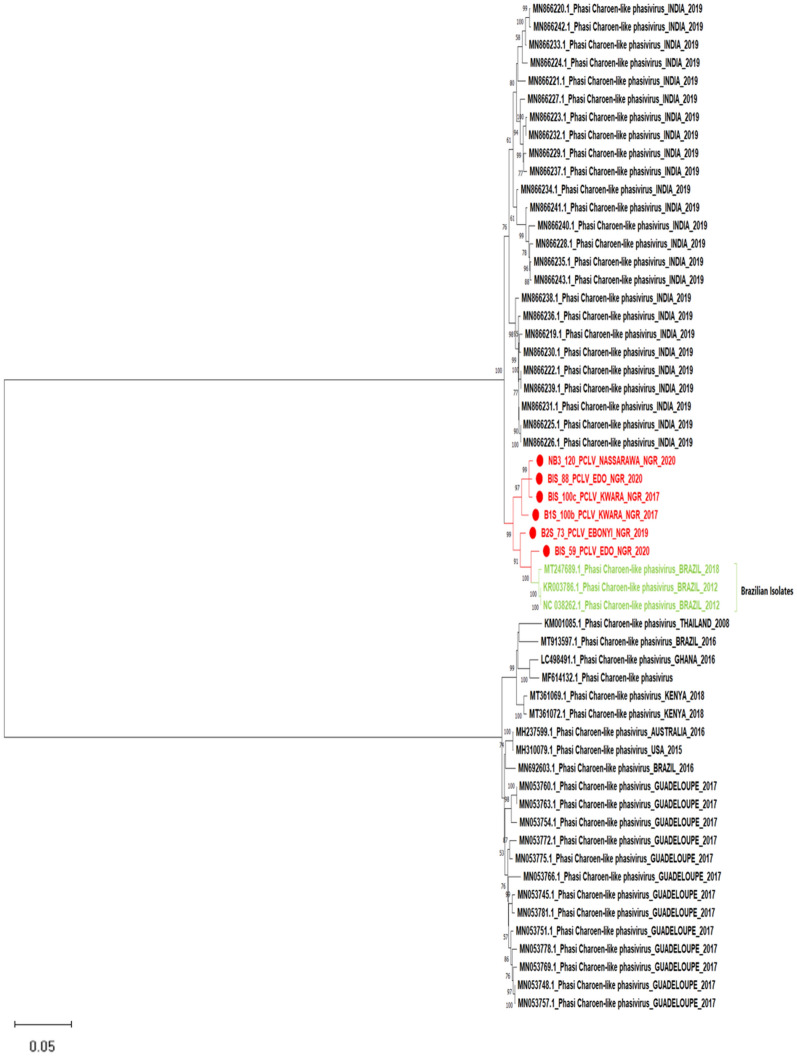

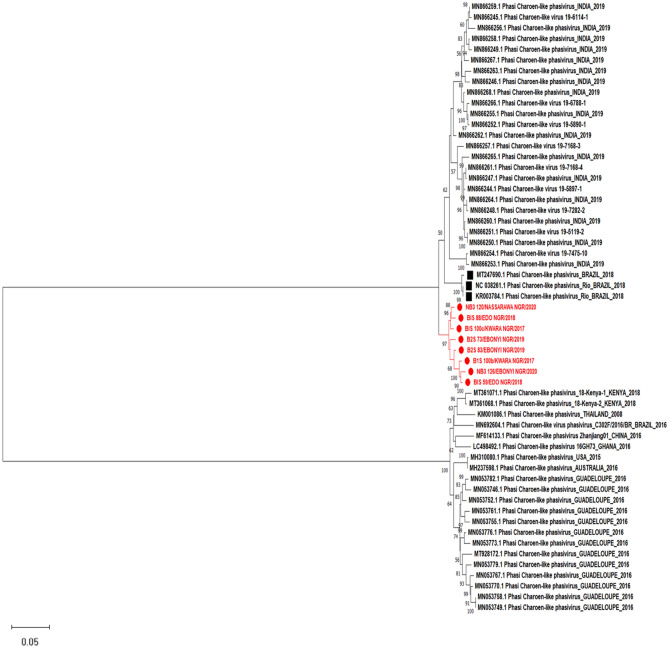

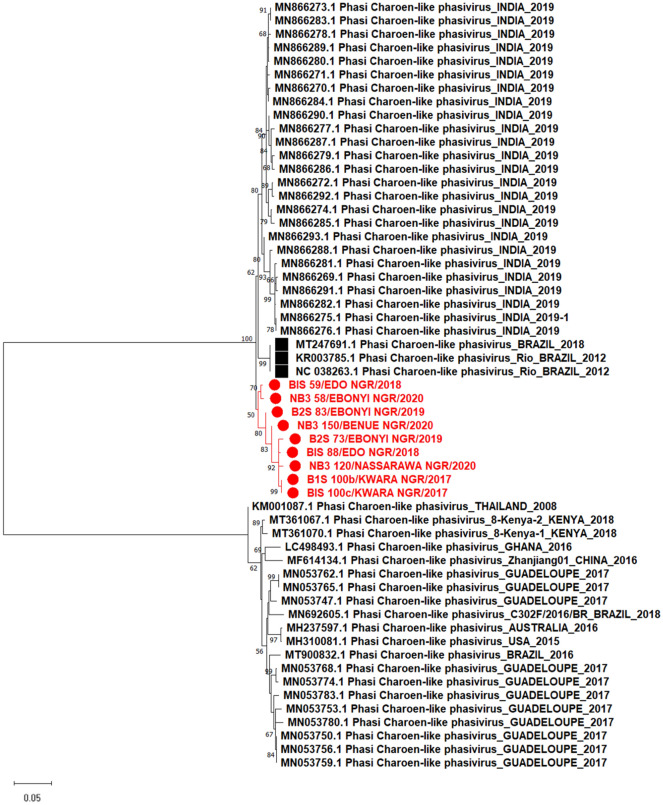

Bunyavirales

Phylogenetic analysis revealed similar clustering patterns across the three segments of the virus in Nigeria. According to states, there is no observed clustering pattern showing the virus's limited diversity in the country (Figs. 3, 4, 5).

Figure 3.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationship between the L segment (RdRp) of Phasi Charoen like phasivirus sequences from this study and those obtained from the NCBI database. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers at branch nodes indicate the bootstrap values ≥ 50%.

Figure 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationship between the M segment (glycoprotein) of Phasi Charoen like phasivirus sequences from this study and those obtained from the NCBI database. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers at branch nodes indicate the bootstrap values ≥ 50%.

Figure 5.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree showing evolutionary relationship between the S segment (Nucleocapsid) of Phasi Charoen like phasivirus sequences from this study and those obtained from the NCBI database. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The numbers at branch nodes indicate the bootstrap values ≥ 50%.

Other viruses (Tesano Aedes Virus, Chaq-like virus, Fako virus and Verdadero virus) were assembled from our sequenced data. We did not construct phylogenetic trees due to the lack of substantial genomes on NCBI for proper comparison. In which cases, only one to three genomes are available in the database.

The percentage similarity for these viruses assembled from this study is detailed in Tables 2 and 4.

Table 2.

Genome characterization of Fako virus genome described in this study.

| Segment (accession no.) | Segment length (bp) | ORF length (aa) | Protein | Encoded gene | Closest strain in GenBank | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM522898 | 2398 | 132 | VP2 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | KM978429.1 | 94.29 |

| OM522899 | 2925 | 213 | VP3 | Major capsid protein | KM978432.1 | 98.22 |

| OM522900 | 3176 | 528 | VP4 | Nonstructural protein | KM978433.1 | 97.95 |

| OM522901 | 2983 | 286 | VP5 | Turret protein | KM978436.1 | 97.00 |

Table 4.

Assembly and Genome characterization of members of Iflaviridae, Partitiviridae, Flaviviridae and Totiviridae described in this study.

| Family | Genus (genome type) | Species | Isolate name | GenBank accession number | Genome length (bp) | Closest strain in GenBank | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iflaviridae | Unclassified ssRNA ( +) | Tesano virus | B1S_88_T | OM522841 | 9310 | LC496784.1 (16GH47) | 93.30 |

| B1S_100c_T | OM522842 | 9339 | LC496784.1 (16GH47) | 97.17 | |||

| NB3_120_T | OM522845 | 9193 | LC496784.1 (16GH47) | 92.66 | |||

| NB3_150_T | OM522843 | 9313 | LC496784.1 (16GH47) | 98.15 | |||

| Partitiviridae | Unclassified Partitivirus (dsRNA) | Chaq-like virus | B1S_100b_Cv | OM522892 | 1377 | MT742176.1 | 98.77 |

| Verdadero virus | B1S_100b_V | OM522895 | 1313 | MT742174.1 | 95.83 | ||

| Flaviviridae | Unclassisfied Flavivirus ssRNA( +) | Cell fusing agent virus | B2S_50_CFAV | OM522840 | 4784 | LR694076.1 | 97.79 |

| Totiviridae | dsRNA | Aedes aegypti totivirus | B2S_50_AaT | OM522890 | 7974 | MN053727.1 | 91.83 |

| B2S_51_AaT | OM522889 | 7557 | MN053725.1 | 91.51 | |||

| NB3_58_AaT | OM522886 | 7735 | MN053727.1 | 91.73 | |||

| B2S_83_AaT | OM522888 | 7677 | MN053723.1 | 92.29 | |||

| B2S_100c_AaT | OM522887 | 7953 | MN053723.1 | 92.81 | |||

| NB3_120_AaT | OM522885 | 4766 | MN053726.1 | 92.78 |

Discussion

Several studies have applied metagenomics sequencing in isolating viruses from mosquitoes in Africa16–19. Our study reports the first metagenomics analysis of mosquitoes in Nigeria. Not only did we detect the presence of viral reads from the samples, but all the reads were also sufficient to assemble genome sequences.

We detected the presence of Fako virus, Aedes aegypti totivirus, Cell fusing agent, Tesano Aedes virus, Phasi Charoen-like phasivirus Chaq-like and Verdadero viruses, all of which are being reported for the first time in Nigeria. Chaq-like virus and Verdadero viruses reported in this study are the first reports in Africa.

Our study also highlights the application of next generation sequencing in identifying ISVs and granting insight into the mosquito virome in Nigeria.

Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus were the most common mosquitoes in the study areas. They accounted for > 80% of the pools analyzed in the study. The reason is that our sampling was biased toward Aedes species as essential vectors of YFV. They are also the dominant members of their genus breeding around domestic and peri domestic areas of human habitations20.

We assembled four (segments 2,3,4 and 5) and a partial first segment out of the nine segments of the Fako virus; reovirus of the genus Dinovernavirus. The first report of the virus is in mosquito pools from Cameroun16. This virus is maintained via mosquito to mosquito transmission and might have evolved from its initial ancestor through loss of function activities. There is no report of human infection with FKV. Our genome was isolated from one Aedes aegypti pool from Edo State. Across all segments, our sequences were 96.7% similar to the first sequence from Cameroun (Table 2).

There are seven genomes (four full and three partial) for Tesano Aedes virus (TeAV) in mosquito pools. TeAV is a member of the Iflaviridae family and was first isolated from Mosquito samples in Ghana17. The virus has shown evidence of vertical transmission17. It increases the growth of Dengue virus 1 (DENV-1) in a concentration-dependent manner under laboratory conditions17. Members of this family are known to infect insects with no reports of human infection. On average, our sequences were 96% similar to the only sequence for the TeAV available on NCBI (Table 4).

We had five complete genomes and one partial genome assembly for AaTV. This virus is a member of the Totiviridae family and a group of dsRNA viruses that infect fungi, protozoa, or invertebrates21. AaTV was highly distributed and present in mosquito pools from Kwara and Ebonyi States. Phylogenetic analysis of the virus genomes revealed that the Nigerian Strains clustered together in the same major clade, independent of the American/Asian/European lineages, implying continuous evolution and diversity of the virus (Fig. 2). Sequences obtained from the same state (Ebonyi State) clustered closely in a sub-clade on the tree, resulting from the localized spread of the virus among the mosquito vectors in this community.

In addition, we had one partial genome assembly of a flavivirus; Cell fusing agent virus. Many medically important arboviruses belong to the Flaviviridae family. Our sequence shares 97.8% identity with the sequence from Uganda. CFAV is the first ISV reported and named after its characteristic CPE of fusion of cells22. Two decades later, researchers sequenced CFAV in 199223. The virus has been isolated from Aedes species in dengue endemic areas6,24–28. There is a close phylogenetic relationship between insect-specific (ISF) and medically important flaviviruses. This information could be valuable in understanding how ISFs enable/inhibit transmission of arboviruses in nature and their possible use as agents of biological control of vectors2. A study by Baidaliuk et al., 2019 evaluated how CFAV affects ZIKV and DENV-1 in vitro and vivo29. Their findings showed a negative correlation both in-vitro and in-vivo, indicating a decrease in transmission in both viruses due to the presence of CFAV.

Furthermore, we assembled 13 genomes for the L and M segments, as well as 12 for the S segment of Phasi Charoen-like-phasivirus (PCLV)- a bunyavirus first isolated from the Phasi Charoen district of Thailand from wild-caught Aedes aegypti larvae30. The phylogenetic tree based on the S segment (Nucleocapsid) and M segment (glycoprotein) displayed these segments as being in a separate cluster independent of previously detected lineages (Figs. 3 and 4). However, RdRp sequences encoded by the L segment displayed the PCLV from our study as being in the same clade as RdRp of previously detected PCLV from Aedes aegypti from Brazil in 2012 (Fig. 5). We have characterized our assemblies for the three segments of the virus (Table 3). There may be a link between PCLV and the transmission of arboviruses, e.g., Ae. albopictus cell line Aa23, persistently infected with CFAV, inhibited ZIKV replication and transmission31. At the same time, another study isolated PCLV from Ae. aegypti naturally infected with the Chikungunya virus (CHIKV)32 during an arbovirus surveillance program. The relationship between PCLV and CHIKV transmission is still unknown and needs further investigation.

Table 3.

Genome characterization of Phasi Charoen-like phasivirus genome described in this study.

| Segment | Strain name | Segment (accession_no) | Segment length (bp) | ORF length (aa) | Encoded gene | Closest strain in GenBank | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | B1S_100b_PCLP | OM522847 | 6781 | 2217 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MT361069.1 | 97.50 |

| B2S_48_PCLP | OM522851 | 6156 | 279 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MN053766 | 98.44 | |

| B2S_73_PCLP | OM522854 | 6471 | 351 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MT361069.1 | 97.62 | |

| B2S_83_PCLP | OM522855 | 5906 | 316 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MT361069.1 | 95.93 | |

| B1S_59_PCLP | OM522848 | 6731 | 2217 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MH237599.1 | 98.60 | |

| B1S_88_PCLP | OM522849 | 6738 | 2217 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MT361069.1 | 97.58 | |

| B1S_100c_PCLP | OM522856 | 6514 | 837 | RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | MT361069.1 | 92.00 | |

| M | B1S_100b_PCLP | OM522860 | 3819 | 1237 | Glycoprotein | MH237598.1 | 97.07 |

| B2S_48_PCLP | OM522870 | 3564 | 501 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 97.41 | |

| B2S_50_PCLP | OM522869 | 3346 | 192 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 96.84 | |

| B2S_73_PCLP | OM522871 | 3521 | 1492 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 97.13 | |

| B2S_83_PCLP | OM522868 | 3600 | 620 | Glycoprotein | MN053782.1 | 95.72 | |

| B1S_59_PCLP | OM522861 | 3768 | 1237 | Glycoprotein | MH237598.1 | 96.97 | |

| B1S_88_PCLP | OM522862 | 3833 | 1237 | Glycoprotein | MH237598.1 | 94.04 | |

| B1S_100c_PCLP | OM522867 | 3593 | 558 | Glycoprotein | MH237598.1 | 97.84 | |

| NB3_58_PCLP | OM522866 | 3354 | 217 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 98.20 | |

| NB3_120_PCLP | OM522863 | 3768 | 1237 | Glycoprotein | MH237598.1 | 97.21 | |

| NB3_126_PCLP | OM522872 | 3614 | 552 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 96.77 | |

| NB3_150_PCLP | OM522865 | 3620 | 350 | Glycoprotein | MN053776.1 | 97.57 | |

| S | B1S_100b_PCLP | OM522873 | 1331 | 268 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.31 |

| B2S_73_PCLP | OM522876 | 769 | 250 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 95.84 | |

| B2S_83_PCLP | OM522882 | 728 | 109 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 97.67 | |

| B1S_59_PCLP | OM522877 | 1326 | 268 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.98 | |

| B1S_88_PCLP | OM522878 | 1331 | 268 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.53 | |

| B1S_100c_PCLP | OM522879 | 861 | 265 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.28 | |

| NB3_58_PCLP | OM522884 | 1290 | 199 | Nucleocapsid | MT361067.1 | 95.06 | |

| NB3_120_PCLP | OM522880 | 1325 | 268 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.00 | |

| NB3_126_PCLP | OM522881 | 665 | 189 | Nucleocapsid | MT361067.1 | 98.05 | |

| NB3_150_PCLP | OM522883 | 1024 | 117 | Nucleocapsid | MN866293.1 | 96.62 |

Partitiviruses are known to infect a vast host, including plants, fungi with some members of this genus recently discovered in arthropods8,33,34. In this study, three (3) Chaq-like viruses were found from Aedes spp pools. The BLASTn search results of the three sequences from our study showed high nucleotide sequence identity (98.7%) to strain CLv.PozaRica20 (MT742176.1) was isolated from Aedes aegypti in Mexico in 2020. Showing the virus may be widely disseminated in the mosquito vector. Only three sequences are available on NCBI for this virus as of 23rd of October 2021, with limited information.

Another Partivirus genome assembled in this study is the Verdadero virus (Table 4; Fig. 6). Verdadero virus was first isolated from Aedes aegypti colony from Poza Rica, Mexico. The name of the virus was derived from the Spanish word for “true” Verdadero7. There is no report on human infection by this virus. Generally, we did not observe any unique differences in viruses detected between male and female mosquito pools from the same collection site.

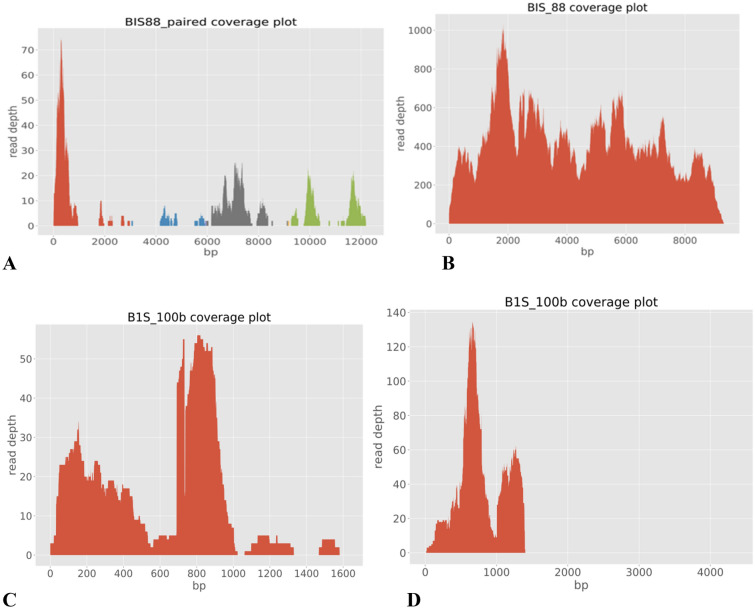

Figure 6.

Coverage plot for (A) Fako virus segments, (B) Tesano Aedes virus, (C) Chaq like virus, (D) Verdadero virus. (A) Red = Segment 1, Blue = Segment 2, Grey = Segment 3 and Green = Segment 4.

Generally, reports on the effects of ISVs on pathogenic arbovirus transmissions are controversial and conflicting from various studies and in vivo/in vitro conditions.

Although ISVs cannot grow in mammalian cell lines, a study in Brazil isolated a novel insect-specific virus, Guapiaçu virus (GUAPV), from the plasma sample of a febrile person9. Furthermore, the discovery of ISVs within the families of pathogenic viruses provided insights into the evolution and adaptation of these groups of viruses35. For example, ISVs belonging to Flaviviridae and Bunyaviridae families are thought to be ancient viruses with distinct lineages that have evolved at the same time and diversified with their vector hosts10,36,37. Studies establishing vertical transmission24,38 and evidence of ISVs genomic sequence integration in the genome of insect vectors39 have supported the hypothesis. Against this background, many pathogenic arboviruses probably gained their dual-host range by an adaptive evolution process that conferred the ability to infect vertebrates to ISVs. There is limited information on the pathogenicity of ISVs to their insect host. Furthermore, ISVs were considered possible biological control agents for vectors and arboviruses of public health importance due to their characteristic lack of replication in mammalian cell lines. Given all these possible applications of ISVs, they are an exciting group of viruses for further investigations.

We could not detect YFV from this study, possibly because of our small amount of virus in the vectors that could not be properly amplified in the vectors. This could also be due to limitations in the protocol we used to construct the genomic libraries. Although we have used the same protocol to sequence and assemble YFV in human samples13 successfully. An approach targeted at enriching the Yellow fever virus in the mosquito vectors could have resulted in potential YFV assembly.

Identifying these diverse groups of viruses (ISVs) from our study is a first step in applying local genomics capacity within the country for a holistic approach to disease outbreaks. Further investigation of the pathogenic potential of these viruses, how they enhance/inhibit transmission of circulating arboviruses in Nigeria needs to be carried out.

Methods

Sample description

During active yellow fever virus outbreaks, mosquito samples were trapped across nine (9) states in Nigeria between 2017 and 2020 for metagenomic sequencing. Generally, three trapping methods were used in this study; egg, larval and adult collections. At each sampling point, the coordinates were taken using a global positioning system (GPS) gadget as described by40. Live adult mosquitoes collected in the field were immobilized using Ethyl Acetate. A total of 15 pools were mosquitoes collected at the immature stages and reared to the adult stage, while 11 pools were from mosquitoes collected directly as adults. These adult mosquitoes were unfed and hungry, as they were collected foraging for blood meal. All adult mosquitoes collected were morphologically identified to species level using keys of41–43 and then pooled based on species and sex into 50 mosquitoes per pool. They were then introduced into well-labelled Eppendorf tubes containing RNAlater. The tubes were stored in freezers for the duration of the surveillance to keep the samples genetically intact. Immature stages (pupae and larvae) are reared to adults before pooling.

A cohort of samples making 26 pools of 1,300 mosquitoes were sequenced. Twenty-five (25) pools were Aedes spp (Aedes aegypti, Aedes albopictus, Aedes luteocephalus, Aedes simpsoni, Aedes simpsoni complex) and one pool of Anopheles coustani (Supplementary Table S1). Mosquitoes were trapped by the National Arbovirus and Vectors Research Centre (NAVRC), Enugu, Enugu State, Nigeria.

RNA extraction and metagenomics sequencing

A total of 1300 mosquitoes made into twenty-six (26) mosquito pools were sequenced based on the established unbiased protocol14. Briefly, Vector pools were initially homogenized in 1 ml of cooled Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (composition-500 ml DMEM High Glucose (4.5 g/I) with l-Glutamine), 1 ml Penicillin–Streptomycin, 15 ml Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) 3% and 5 ml Amphotericin B) and 500 ml of Zirconia beads (Firma Biospec: 2.0 mm, Cat. No 1107912). The contents were macerated for 10 min on the Qiagen Tissuelyser LT followed by centrifuging at 4500×g for 15 min. According to the manufacturer's instructions, the supernatant was further used for RNA extraction using the QIAamp Viral RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Extracted RNA was turbo Dnased to remove contaminating DNA and cDNA synthesis was carried out according to the published protocol13,14. Sequencing libraries were made using the Illumina Nextera XT kit. Next generation sequencing using Illumina Miseq V2-500 cycle kit at 251 read length paired-end sequencing was carried out on Illumina Miseq at the African Centre of Excellence for Genomics of Infectious Diseases (ACEGID), Redeemer's University, Ede, Nigeria.

Sequencing reads quality control

We added nuclease-free water (NTC) as a negative control for each sample preparation step. Before subsequent downstream analysis, we checked the water control for possible contaminations. All sequencing reads taxonomically classified as a given virus were first checked against possible reads from the NTC. We did a reference mapping of our reads against reference genomes on NCBI to rule out false positives. For this study, we only report viruses for which genomes are assembled.

Bioinformatics analysis

Bioinformatics analysis was carried out on the sequence data generated to identify viruses present in the samples. First, we demultiplexed individual libraries and removed reads mapping to the human genome or other known technical contaminants (e.g., sequencing adapters). Raw reads from the sequencing machine were passed through Microsoft’s Premonition metagenomics pipeline (https://innovation.microsoft.com/en-us/premonition). We also carried out genome assembly of individual viruses detected using our publicly available viral-ngs15,44 and VGEA pipelines45.

Assembled genomes were annotated using ORFfinder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) with a 300-nt minimum length and the genome structure was annotated using NCBI Conserved Domain Database version 3.19 (expected value threshold of 1 × 10–2) with the NCBI viral genome database as references.

Multiple alignments of nucleotide sequences and deduced amino acids with those of reference strains from GenBank were analyzed using the MAFFT online version46. To determine the phylogenetic relationship of viruses detected from the mosquito pools, reference nucleotide sequences representing Aedes aegypti totivirus and Phasi Charoen-like phasivirus (strains with all three segments) were obtained from GenBank. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Likelihood method and Tamura-Nei model47 with 1000 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap support is indicated by values on branches. Evolutionary analysis was conducted in MEGA X version 10.1.848.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work is made possible by support from ACEGID lab and a cohort of generous donors through TED’s Audacious Project, including the ELMA Foundation, MacKenzie Scott, the Skoll Foundation, and Open Philanthropy. This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (https://www.niaid.nih.gov), NIH-H3Africa (https://h3africa.org) (U01HG007480 and U54HG007480), the World Bank grants (project ACE-019 and ACE-IMPACT), the Rockefeller Foundation (Grant #2021 HTH), the Africa CDC through the African Society of Laboratory Medicine [ASLM] (Grant #INV018978), the Wellcome Trust (Project 216619/Z/19/Z), and the Science for Africa Foundation. We would like to appreciate Clementina Chekwube Anioke, Francis Uzoma Orizu, Esther Ngozi Onuora, Linda Chioma Ikechukwu, and Oscar Nnanna Nwaogo for their assistance during sample collections.

Author contributions

J.U.O.-performed NGS on samples, initial data review and bioinformatics analysis and wrote the manuscript, P.E.O. and U.E.G.-carried out bioinformatics analysis and wrote the manuscript. T.J.O., B.E.B. and F.O.B.-performed NGS and contributed to the first draft of the manuscript. A.K.-performed the statistical analysis. U.C.N., C.C.A. F.A.D., C.O.O., E.K.E., N.O.A., E.I.E., S.O.A., A.I.O., E.M.N., S.O.E., G.K.O, N.E.U, J.M and I.M.N. collected, identified and preserved the mosquito samples; C.O.M., C.I., O.C.C., C.C.A. and J.C.O. supervised sample collection, identification and preservation of the mosquito samples. O.A.F., and I.O.O.K. reviewed the manuscript. C.T.H.-conceived the study, supervised the NGS experiment, data analysis and discussions and reviewed the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All the sequences from this study are available on github: https://github.com/acegid/Vector_Genomics_Study and on NCBI with accession numbers OM522840- OM522901.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-11797-2.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. A Global Brief on Vector-Borne Diseases. (2014).

- 2.Blitvich BJ, Firth AE. Insect-specific flaviviruses: A systematic review of their discovery, host range, mode of transmission, superinfection exclusion potential and genomic organization. Viruses. 2015;7:1927–1959. doi: 10.3390/v7041927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasilakis N, Tesh RB. Insect-specific viruses and their potential impact on arbovirus transmission. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2015;15:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cholleti H, et al. Discovery of novel viruses in mosquitoes from the Zambezi Valley of Mozambique. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0162751. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman H, et al. Characterization of three new insect-specific Flaviviruses: Their relationship to the mosquito-borne Flavivirus pathogens. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2018;98:410–419. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zakrzewski M, et al. Mapping the virome in wild-caught Aedes aegypti from Cairns and Bangkok. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:4690. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22945-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross ST, et al. Partitiviruses infecting Drosophila melanogaster and Aedes aegypti exhibit efficient biparental vertical transmission. J. Virol. 2020;94:1070. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01070-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faizah AN, et al. Deciphering the virome of Culex vishnui subgroup mosquitoes, the major vectors of Japanese encephalitis, in Japan. Viruses. 2020;12:264. doi: 10.3390/v12030264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Oliveira Ribeiro G, et al. Guapiaçu virus, a new insect-specific flavivirus isolated from two species of Aedes mosquitoes from Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:4674. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-83879-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marklewitz M, Zirkel F, Kurth A, Drosten C, Junglen S. Evolutionary and phenotypic analysis of live virus isolates suggests arthropod origin of a pathogenic RNA virus family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:7536–7541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502036112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi M, et al. Redefining the invertebrate RNA virosphere. Nature. 2016;540:539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature20167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Halbach R, Junglen S, van Rij RP. Mosquito-specific and mosquito-borne viruses: Evolution, infection, and host defense. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2017;22:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ajogbasile FV, et al. Real-time metagenomic analysis of undiagnosed fever cases unveils a yellow fever outbreak in Edo State, Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:3180. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59880-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matranga CB, et al. Unbiased deep sequencing of RNA viruses from clinical samples. J. Vis. Exp. 2016 doi: 10.3791/54117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park, D. et al. broadinstitute/viral-ngs: v1.19.2. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/record/1167849 (2018).

- 16.Auguste AJ, et al. A newly isolated reovirus has the simplest genomic and structural organization of any reovirus. J. Virol. 2015;89:676–687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02264-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amoa-Bosompem M, et al. Entomological assessment of the status and risk of mosquito-borne arboviral transmission in Ghana. Viruses. 2020;12:147. doi: 10.3390/v12020147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atoni E, et al. Metagenomic virome analysis of Culex mosquitoes from Kenya and China. Viruses. 2018;10:30. doi: 10.3390/v10010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fauver JR, et al. West African Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes harbor a taxonomically diverse virome including new insect-specific flaviviruses, mononegaviruses, and totiviruses. Virology. 2016;498:288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abílio AP, et al. Distribution and breeding sites of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in 32 urban/peri-urban districts of Mozambique: Implication for assessing the risk of arbovirus outbreaks. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2018;12:e0006692. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghabrial SA, Nibert ML. Victorivirus, a new genus of fungal viruses in the family Totiviridae. Arch. Virol. 2009;154:373–379. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stollar V, Thomas VL. An agent in the Aedes aegypti cell line (Peleg) which causes fusion of Aedes albopictus cells. Virology. 1975;64:367–377. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90113-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cammisa-Parks H, Cisar LA, Kane A, Stollar V. The complete nucleotide sequence of cell fusing agent (CFA): Homology between the nonstructural proteins encoded by CFA and the nonstructural proteins encoded by arthropod-borne flaviviruses. Virology. 1992;189:511–524. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90575-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook S, et al. Isolation of a new strain of the flavivirus cell fusing agent virus in a natural mosquito population from Puerto Rico. J. Gen. Virol. 2006;87:735–748. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espinoza-Gómez F, et al. Detection of sequences from a potentially novel strain of cell fusing agent virus in Mexican Stegomyia (Aedes) aegypti mosquitoes. Arch. Virol. 2011;156:1263–1267. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-0967-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoshino K, Isawa H, Tsuda Y, Sawabe K, Kobayashi M. Isolation and characterization of a new insect flavivirus from Aedes albopictus and Aedes flavopictus mosquitoes in Japan. Virology. 2009;391:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kihara Y, et al. Rapid determination of viral RNA sequences in mosquitoes collected in the field. J. Virol. Methods. 2007;146:372–374. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamanaka A, Thongrungkiat S, Ramasoota P, Konishi E. Genetic and evolutionary analysis of cell-fusing agent virus based on Thai strains isolated in 2008 and 2012. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2013;19:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baidaliuk A, et al. Cell-fusing agent virus reduces Arbovirus dissemination in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes in vivo. J. Virol. 2019;93:00705. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00705-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamao T, et al. Novel virus discovery in field-collected mosquito larvae using an improved system for rapid determination of viral RNA sequences (RDV ver4.0) Arch. Virol. 2009;154:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz MJ, Frydman HM, Connor JH. Dual Insect specific virus infection limits Arbovirus replication in Aedes mosquito cells. Virology. 2018;518:406–413. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2018.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunha MDP, et al. A metagenomic approach identified a novel Phasi Charoen-like virus coinfecting a Chikungunya virus-infected Aedes aegypti mosquito in Brazil. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2020;9:1572. doi: 10.1128/MRA.01572-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nibert ML, et al. Taxonomic reorganization of family Partitiviridae and other recent progress in partitivirus research. Virus Res. 2014;188:128–141. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pettersson JH-O, et al. Characterizing the virome of Ixodes ricinus ticks from northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10870. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11439-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Öhlund P, Lundén H, Blomström A-L. Insect-specific virus evolution and potential effects on vector competence. Virus Genes. 2019;55:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s11262-018-01629-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cook S, et al. Novel virus discovery and genome reconstruction from field RNA samples reveals highly divergent viruses in dipteran hosts. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e80720. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li C-X, et al. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. Elife. 2015;4:5376. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolling BG, Eisen L, Moore CG, Blair CD. Insect-specific flaviviruses from Culex mosquitoes in Colorado, with evidence of vertical transmission. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2011;85:169–177. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2011.10-0474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roiz D, Vázquez A, Seco MPS, Tenorio A, Rizzoli A. Detection of novel insect flavivirus sequences integrated in Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northern Italy. Virol. J. 2009;6:93. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Booman M, et al. Using a geographical information system to plan a malaria control programme in South Africa. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000;78:1438–1444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Edwards, W. F. & British Museum (Natural History). Mosquitoes of the Ethiopian Region. Vol. III. (British Museum, 1941).

- 42.Gillett, D., J., Smith & G., J. Common African Mosquitos and Their Medical Importance. (Heinemann Medical, 1972).

- 43.Gillies, T. M., & Coetzee, M. A Supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa South of the Sahara (Afrotropical Region). (South African Institute for Medical Research, 1987).

- 44.Park DJ, et al. Ebola virus epidemiology, transmission, and evolution during seven months in Sierra Leone. Cell. 2015;161:1516–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oluniyi PE, et al. VGEA: An RNA viral assembly toolkit. PeerJ. 2021;9:e12129. doi: 10.7717/peerj.12129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: Multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 2019;20:1160–1166. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamura K, Nei M. Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1993;10:512–526. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018;35:1547–1549. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the sequences from this study are available on github: https://github.com/acegid/Vector_Genomics_Study and on NCBI with accession numbers OM522840- OM522901.