Abstract

Background

Gemcitabine (Gem) alone or with Nab-paclitaxel (Gem-Nab) is used as second-line treatment for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (mPA) after FOLFIRINOX (FFX) failure; however, no comparative data exist. This study evaluates the efficacy and safety of adding Nab-paclitaxel to Gem for mPA after FFX failure.

Methods

In this retrospective real-world multicenter study, from 2011 to 2019, patients with mPA receiving Gem-Nab (Gem 1000 mg/m² + Nab 125 mg/m², 3 out of 4 weeks) or Gem alone were included after progression on FFX.

Results

A total of 427 patients were included. Patients receiving Gem-Nab had more metastatic sites, peritoneal disease and less PS 2 (24% vs. 35%). After median follow-up of 22 months, Gem-Nab was associated with better disease control rate (DCR) (56% vs. 32%; P < 0.001), progression-free survival (PFS) (3.5 vs. 2.3 months; 95% CI: 0.43–0.65) and overall survival (OS) (7.1 vs. 4.7 months; 95% CI: 0.53–0.86). After multivariate analysis, Gem-Nab and PS 0/1 were associated with better OS and PFS. Grade 3/4 toxicity was more frequent with Gem-Nab (44% vs. 29%).

Conclusion

In this study, Gem-Nab was associated with better DCR, PFS and OS compared with Gem alone in patients with mPA after FFX failure, at the cost of higher toxicity.

Subject terms: Pancreatic cancer, Outcomes research

Introduction

The incidence of pancreatic cancer is constantly increasing and, according to projections, it will become the fifth most common cancer worldwide [1] by 2030. By the same year, mortality by metastatic pancreatic cancer (mPA) will be the second most common cause of cancer-related death. Furthermore, mPA is one of the most aggressive cancers with a median overall survival (OS) of less than 12 months.

Until 2011, gemcitabine (Gem) was a standard treatment for mPA. Since then, the PRODIGE 4 trial [2] has shown a significant increase in the mOS with the FOLFIRINOX (FFX) regimen (5FU, oxaliplatin and irinotecan) compared to gemcitabine (11.2 vs. 6.8 months). A second improvement was demonstrated in the MPACT trial [3], during which Gem combined with Nab-paclitaxel (Gem-Nab) showed a mOS of 8.5 months, versus 6.7 months compared to Gem as a first-line treatment. Depending on the patient’s condition, FFX and Gem-Nab are the two first-line regimens now recommended by most guidelines.

Second-line treatment is influenced by first-line treatment choice. Indeed, both FOLFOX [4] and 5FU-Nal-iri [5] demonstrated efficacy and can be recommended after failure of Gem-based first-line treatment, even if Nal-iri has never been compared to irinotecan, and FOLFOX was not shown to be superior to 5FU alone in a Canadian trial [6]. However, neither of these regimens appear relevant after the failure of FFX. Recently, Macarulla Mercadé et al. also showed that 5FU-Nal-iri does not provide any benefit after previous use of irinotecan [7]. Therefore, moving to a Gem-based second-line treatment after FFX appears more appropriate. However, to our knowledge, only a few small retrospective studies have reported the use of Gem alone, with limited results [8–10]. We previously reported the use of Gem-Nab in this situation, with encouraging preliminary results in a small cohort of 57 patients, with a median progression-free survival (PFS) and OS of 5.1 and 18 months, respectively [11]. However, to our knowledge, the combination of Gem and Nab-paclitaxel has never been compared in this setting to Gem alone. Therefore, we performed a population-based multicenter study on patients treated with Gem-Nab or Gem alone to evaluate efficacy and safety as second-line treatment after FFX failure.

Patients and methods

Population

Data were retrospectively collected in 18 French Association des gastro-entérologues oncologues (AGEO) centres between January 2011 and December 2019 from consecutive patients diagnosed with mPA and with either progressive disease or unacceptable toxicity after FFX treatment and receiving Gem-based second-line treatment (either Gem or Gem-Nab). The administration of a Gem-based regimen was decided by a multidisciplinary board in each centre. The use of Nab-paclitaxel was decided according to its availability in each centre since Nab-paclitaxel is not reimbursed in France and was not available before 2013, as in all European countries. Patients receiving Gem alone were theoretically eligible for Gem-Nab treatment and included in centres where Nab-paclitaxel was not available at the time of treatment.

Inclusion criteria were: a performance status (PS) of 0–2, histologically proven pancreatic adenocarcinoma, measurable metastatic disease, treated with FFX in the first-line setting and treated with Gem or Gem-Nab in the second-line setting. Patients presenting abnormal bilirubin levels, extreme age (>80) and PS > 2 were not included, since they were not eligible for Gem-Nab treatment. For both groups, the following tumour-related informations were collected: date of diagnosis, stage at diagnosis, stage at first-line treatment and location of primary tumour and metastases. Data were retrieved from patients’ files for the Gem-Nab group and on a pre-existing register for patients receiving Gem alone.

Chemotherapy regimens

For the Gem-Nab group, treatment consisted of a 60-min infusion of Nab-paclitaxel at a dose of 125 mg/m² followed by a 30-min infusion of Gem at a dose of 1000 mg/m² on days 1, 8 and 15 every 4 weeks, as previously reported [3]. Treatment was delivered until either disease progression or unacceptable treatment toxicity was reached. In the Gem group, treatment consisted of a 30-min infusion of Gem at a dose of 1000 mg/m² on days 1, 8 and 15 every 4 weeks, as previously reported [12].

The treatment effect was measured by CT scan every 2 to 3 months, according to RECIST 1.1.

Chemotherapy-related toxicities were evaluated in line with the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI-CTCAE) V4.03 and managed by dose reduction of one or both drugs at the discretion of the physician.

Statistical analysis

Median (interquartile and range) values and proportions (percentage) were provided for the description of continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

The primary endpoint was to compare the PFS obtained with Gem-Nab and Gem alone. The secondary endpoints were OS, objective response rate (ORR) according to RECIST 1.1 and safety. PFS was defined as the time from the start of second-line chemotherapy to disease progression or death, whichever occurred first. Patients alive without disease progression were censored at the date of the last follow-up. OS was defined as the time from the start of second-line chemotherapy to the date of death. Disease progression was defined according to RECIST 1.1 criteria or clinical progression.

PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. The association between survival endpoints and potential prognostic factors was assessed with Cox regression models. First, we performed a univariate analysis. Variables with P value <0.10 or clinically relevant, like age >75 years, PS > 1 and longer time-to-progression under first-line treatment were included in a multivariable model. Correlative analysis was performed in the following predefined subgroups: age >65 years, time-to-progression under FFX, PS and baseline Ca19-9 level. All P values ≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analysis was undertaken using the R-Studio software.

Study

This study was conducted in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki, and in accordance with Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. All included patients, alive at the time of data collection, were informed and agreed to the use of their medical records for clinical research purposes. The collection and the treatment of the data were conducted according to the MR 004 authorisation, registered at the Commission National Informatique et Liberté (CNIL).

Results

Patient characteristics

Overall, 427 consecutive patients were included, 208 patients in the Gem-Nab group and 219 in the Gem group across the 18 centres. Ten centres included only patients receiving Nab-paclitaxel. As Nab-Paclitaxel was not available at the same time in all centres, four centres included patients in both groups, since Nab-Paclitaxel became available at a later time during the study period. These centres included patients eligible for Gem-Nab and receiving Gem alone before Nab-paclitaxel availability and included patients receiving Gem-Nab after. Patients receiving Gem alone after Nab-paclitaxel availability because of explicit contraindications were not included. In four centres, only patients receiving Gem alone but eligible to Gem-Nab were included, since Nab-paclitaxel was not available during the whole study duration. The median age was 63 years (range: 30–80) and PS was 0/1/2 in 13%/57%/29%, respectively.

Baseline characteristics were comparable in both groups (Table 1) except for patients with >2 metastatic sites (15% vs. 7%; P = 0.027) and with peritoneal disease (40% vs. 20%, P < 0.001), who were more frequent in the Gem-Nab group. Patients in the Gem-Nab group had statistically more non-metastatic disease at diagnosis but all patients presented a metastatic disease at the time of Gem-Nab or Gem treatment. Conversely, patients with PS 2 were less frequent in the Gem-Nab group (24% vs. 35%; P = 0.036). Patients, on average, had more cycles of FFX as first-line treatment in the Gem-Nab group, with a median number of cycles of 11 [5; 14] vs. 8 [4; 12] (P = 0.001) and yet, disease control rate (DCR) with first-line FFX was lower in Gem-Nab group (58% vs. 69%; P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and baseline characteristics.

| Whole sample (n = 427) | Gem-Nab (n = 219) | Gem (n = 208) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (min; max) | 63 (30–80) | 63 (33–79) | 63 (30–80) | 0.62 | |

| Age category | Age <65 | 267 (62.53%) | 135 (61.64%) | 132 (63.46%) | 0.69 |

| Age ≥65 | 160 (37.47%) | 84 (38.36%) | 76 (36.54%) | ||

| Sex | Women | 191 (44.73%) | 99 (45.21%) | 92 (44.23%) | 0.84 |

| Men | 236 (55.27%) | 120 (54.74%) | 116 (55.77%) | ||

| Performance status (PS) | 0 | 52 (13.4%) | 29 (13.49%) | 23 (13.29%) | 0.04 |

| 1 | 222 (57.22%) | 136 (62.33 %) | 88 (50.87%) | ||

| 2 | 114 (29.38%) | 52 (24.19%) | 62 (35.84%) | ||

| NA | 39 | 4 | 35 | ||

| Stage at diagnosis | Localised | 36 (9.42%) | 26 (11.87%) | 10 (6.13%) | 0.009 |

| Locally advanced | 70 (18.32%) | 48 (21.92%) | 22 (13.5%) | ||

| Metastatic | 276 (72.25%) | 145 (62.21%) | 131 (80.37%) | ||

| NA | 45 | 0 | 45 | ||

| Number of FFX cycles | <4 | 93 (24.47%) | 48 (22.12%) | 45 (27.61%) | 0.001 |

| 4–12 | 205 (53.95%) | 107 (49.31%) | 98 (60.12%) | ||

| >12 | 82 (21.58%) | 62 (28.57%) | 20 (12.27%) | ||

| NA | 47 | 2 | 45 | ||

| Cause of FFX interruption | Disease progression | 310 (89.34%) | 200 (91.32%) | 110 (85.94%) | 0.12 |

| Intolerance/toxicity | 37 (10.66%) | 19 (8.68%) | 18 (14.06%) | ||

| NA | 80 | 80 | |||

| Best response under FFX | Complete response | 1 (0.26%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | <0.001 |

| Partial response | 131 (34.38%) | 53 (24.88%) | 78 (46.43%) | ||

| Stable disease | 110 (28.87%) | 72 (33.8%) | 38 (22.62%) | ||

| Progressive disease | 139 (36.48%) | 88 (41.31%) | 51 (30.36%) | ||

| NA | 46 | 6 | 40 | ||

| Number of metastatic sites | ≤2 | 305 (87.9%) | 186 (84.93%) | 119 (92.97 %) | 0.03 |

| >2 | 42 (12.1%) | 33 (15.07%) | 9 (7.03%) | ||

| NA | 80 | 0 | 80 | ||

| Metastatic sites | Peritoneum | 124 (31.63%) | 89 (40.64%) | 35 (20.23%) | <0.001 |

| Liver | 272 (69.39%) | 156 (71.23%) | 116 (67.05%) | 0.37 | |

| Lung | 81 (23.34%) | 51 (23.29%) | 30 (23.44%) | 0.98 | |

| Bone | 24 (6.92%) | 15 (6.85%) | 9 (7.03%) | 0.95 | |

| Adenopathy | 55 (15.85%) | 50 (22.83%) | 5 (3.91%) | <0.001 | |

| CA19.9 (UI/L) | ≤200 UI/L | 87 (28.62%) | 49 (27.84%) | 38 (29.69%) | 0.73 |

| >200 UI/L | 217 (71.38%) | 127 (72.16%) | 90 (70.31%) | ||

| NA | 123 | 43 | 80 | ||

FFX FOLFIRINOX.

Treatment efficacy

During the study period, 91.7% of patients receiving Gem-Nab and 98.5% of patients receiving Gem discontinued treatment because of disease progression (81.9% for Gem-Nab vs. 90% for Gem), toxicity (9.8% for Gem-Nab vs. 8.6% for Gem) or death. Gem-Nab significantly improved disease control rate (55.9% vs. 32.5%; P < 0.001), with 11.3% of patients presenting partial response under Gem-Nab vs. 8.3% with Gem alone (Table 2).

Table 2.

Objective response rates.

| Best response | Gem-Nab (N = 219) | Gem (N = 208) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partial response—N (%) | 22 (11.28%) | 13 (8.28%) | P < 0.001 |

| Stable disease—N (%) | 87 (44.62%) | 38 (24.2%) | |

| Progressive disease—N (%) | 86 (44.1%) | 106 (67.52%) | |

| NA | 24 | 51 |

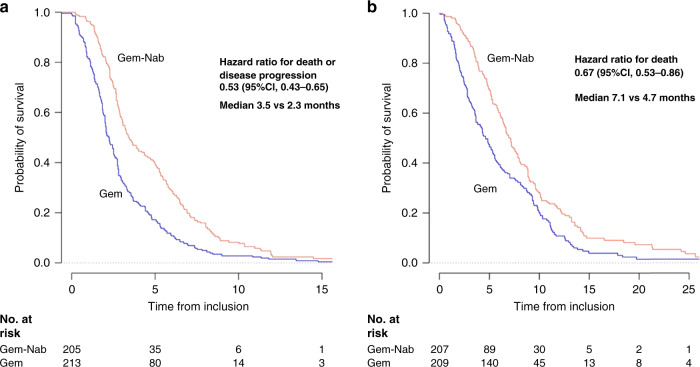

After median follow-up at 22 months (95% CI: [16-not reached, NR]), median PFS was longer in the Gem-Nab group with 3.5 months vs. 2.3 months (Fig. 1a) (HR = 0.53 (95% CI: [0.43–0.65]; P < 0.0001). Median OS was longer in the Gem-Nab group (7.1 months vs. 4.7 months) (HR = 0.67; 95% CI: [0.53–0.86]; P < 0.0001) (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Progression-free and overall survival.

Kaplan–Meier estimates, according to treatment group, of a progression-free survival and b overall survival. Gem-Nab Gemcitabine + Nab-paclitaxel, Gem Gemcitabine, No at risk number of subjects at risk.

Prognostic factors

In univariate analysis, better PS, longer time-to-progression under FFX and Gem-Nab treatment were significantly associated with longer PFS. PS and Gem-Nab treatment were associated with longer OS. In multivariate analysis, Gem-Nab, PS and longer first-line time-to-progression were independent predictors of survival (OS and PFS). Age over 75 years was independently associated with worse PFS but not OS (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cox logistic regression analysis.

| Covariate | Hazard ratio for OS (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio for PFS (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age > 75 y | 1.15 (0.65–2.04) | 0.63 | 1.89 (1.09–3.24) | 0.02 |

| Gem-Nab treatment arm | 0.67 (0.53–0.86) | 0.002 | 0.53 (0.43–0.65) | <0.0001 |

| Liver metastasis | 1.22 (0.94–1.59) | 0.14 | 1.25 (0.99–1.57) | 0.06 |

| Performance status > 1 | 1.90 (1.47–2.45) | <0.0001 | 1.54 (1.23–1.93) | <0.0001 |

| PFS with FFX > 4.17 mo (median) | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.04 | 1.30 (1.06–1.60) | 0.01 |

Subgroup analysis

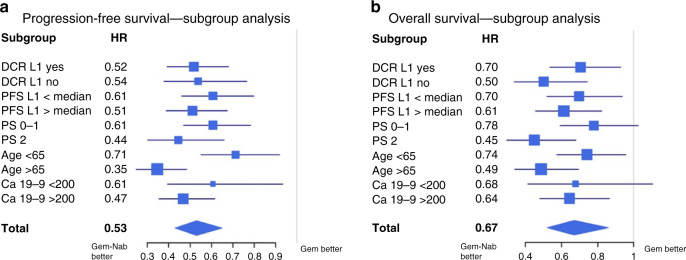

A complementary analysis in predefined subgroups was performed. The longer PFS with Gem-Nab was observed in all subgroups analysed, including patients with PS = 2 (HR = 0.44; 95% CI [0.3; 0.65], P < 0.0001), patients >65 years (HR = 0.35; 95% CI [0.25; 0.49], P < 0.0001), patients with shorter first-line PFS (HR = 0.61; 95% CI [0.46; 0.80], P < 0.0001) and patients with no disease control under FFX (HR = 0.54; 95% CI [0.38; 0.78], P < 0.001) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Subgroup analysis of survival.

a Forest plot of the treatment effect on progression-free survival in subgroup analysis. b Forest plot of the treatment effect on overall survival in subgroup. DCR L1 Disease control rate under first line treatment, PS ECOG performance status.

The same results were observed for OS, with longer OS with Gem-Nab in patients with immediate progressive disease under FFX regimen (HR = 0.50, 95% CI [0.34; 0.74], P < 0.0001), patients with PS = 2 (HR = 0.45, 95% CI [0.30; 0.68], P < 0.0001) and age >65 years (HR = 0.49, 95% CI [0.34; 0.70], P < 0.0001), as shown in Fig 2b.

Safety

Information on treatment-related toxicity was available for 218 patients in the Gem-Nab group and for 124 patients in the Gem group. Patients receiving Gem-Nab presented more toxicity of any grade with 96.4% in comparison with Gem alone 68.6% (P < 0.001). Incidence of grade 3 and 4 adverse events was significantly higher in patients receiving Gem-Nab (43.2% vs. 29.2%).

Grade 3 and 4 neutropenia were reported in 15.14% vs. 10.49% and neuropathy in 10.6% vs. 0%. Nausea, diarrhoea, febrile neutropenia, anaemia, thrombopenia, alopecia, mucositis and fatigue were also more frequently reported in the Gem-Nab group (see Table 4 and Supplementary Table 1). Nevertheless, treatment discontinuation due to treatment toxicity was comparable in both groups (8.41% Gem-Nab vs. 8.59% Gem).

Table 4.

Most common grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurring in patients in the safety population.

| Grade 3 and 4 toxicity | Gem-Nab N = 218* N (%) | Gem N = 124* N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nausea | 10 (4.59%) | 2 (1.61%) |

| Diarrhoea | 3 (1.38%) | 0 (0%) |

| Skin dryness | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Neutropenia | 33 (15.14%) | 13 (10.49%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1 (0.46%) | 0 (0%) |

| Anaemia | 13 (5.96%) | 3 (2.42%) |

| Thrombopenia | 27 (12.39%) | 6 (4.84%) |

| Neuropathy | 23 (10.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Alopecia | 1 (0.46%) | 0 (0%) |

| Mucositis | 3 (1.38%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fatigue | 28 (12.96%) | 19 (15.33%) |

Discussion

In our study, we showed that the combination of Nab-paclitaxel with Gem was associated with significantly improved PFS and OS compared to Gem alone. This effect was observed in all subgroups, and after multivariable analysis adjusted for age, PS, metastatic sites and duration of first-line FFX. The anti-tumour efficacy of the Gem-Nab combination in the second-line setting is also supported by a better DCR compared to Gem (55.9% vs. 32.5%), and this DCR is comparable with previous reports from smaller studies [11, 13]. We can also note that this beneficial effect can be seen in a group of patients, that had less partial response under FFX (24.88% in the Gem-Nab group vs. 46.43% in the Gem group, P < 0.001). This could suggest a more aggressive disease in patients of the Gem-Nab group.

Though limited, the differences seen in OS (difference: 2.4 months) and PFS (difference: 1.2 months) remain clinically relevant considering the particularly poor outcome of patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer after first-line treatment failure.

Of particular note, the subgroup analysis showed that the increased survival with Gem-Nab was still present in patients with PS 2 and patients over 65 years, suggesting that patients with poorer performance status or a higher number of metastatic sites also benefit from more intensive chemotherapy. This effect is generally not assessable in a prospective clinical trial, as these patients are usually excluded.

Our findings are comparable with the results of another study evaluating efficacy and safety of Gem-Nab in elderly patients. It suggests that this chemotherapy regimen is as efficient in patients over 75 years as in younger patients, however at a cost of more adverse events [14].

The safety profile showed a significantly higher incidence of all grade toxicity (95.6% vs. 68.5%) and a higher proportion of patients showing grade 3 and 4 toxicity (43.2% vs. 29.2%) in the Gem-Nab group. These findings were consistent with previously reported results [3, 11]. The most frequent adverse events were neuropathy, neutropenia and diarrhoea. Most of the time, the resolution of toxicity was spontaneous without the need for specific treatment. We observed statistically more neutropenia in the Gem-Nab group concerning grade 2, 3 and 4 neutropenia with respectively 14.22%/12.39%/2.75% vs. 5.65%/9.68%/0.81% (P = 0.03). However, the incidence of febrile neutropenia was very low, with only one patient in the Gem-Nab group and no patient in the Gem group. This could be explained by the frequent use of G-CSF, but data on G-CSF use was not systematically collected in patients’ files and could therefore not be retrieved for analysis. Neuropathy was also an important concern after first-line FFX, with a frequent sequelae neuropathy after oxaliplatin-based regimen. Grade 3/4 neuropathy has been reported in approximately 4% of patients treated with a taxane-based second-line treatment [15] and reported in 0 to 7.5% of patients treated with oxaliplatin-based regimens [4,16–18]. We noticed in our study, that there was significantly more grade 2 neuropathy after Gem-Nab treatment (25.4 % vs 1.61%), which could have an impact on the quality of life of patients (QoL). In addition, 10% of patients reported severe neurotoxicity, all treated with Gem-Nab. However, this represents a much lower incidence than in the MPACT trial, even though patients in our study previously received another neurotoxic treatment. In addition, neuropathy did not appear to be limiting in the majority of cases, as the duration of treatment was longer with Gem-Nab than with Gem. Since the study was an observational study, dose modifications were not standardised. It is known that Nab-paclitaxel- and Oxaliplatin-induced neurotoxicity are different and so is their reversibility. Oxaliplatin causes symmetrical paraesthesia and distal hypaesthesia; symptoms can worsen even after treatment cessation and can last for several years. Nab-paclitaxel also causes paraesthesia and distal burning pain, but generally has a rapid improvement over a few months after treatment cessation [19]. Therefore, the impact of neurotoxicity due to Nab-paclitaxel seems less severe on patients’ QoL, even though grading is equivalent.

Safety estimation in our study is likely incomplete due to its retrospective feature. Although significant toxicities were systematically reported for most of the patients, 84 patients treated with Gem were removed from the safety analysis due to missing data in the pre-existing register file. These registries provided access to individual data, however, the data collected was not exhaustive, and we were unable to access source data for these patients. Moreover, there is no evaluation of QoL in our study, which is an important benchmark of palliative chemotherapy. However, a randomised study evaluating QoL of patients under both regimens in the first-line setting showed that there was less QoL deterioration in patients treated with Gem-Nab regimen compared to Gem alone at 3 and 6 months timepoints of treatment and with similar survival rates to our study [20]. Gem-Nab can therefore be considered a safe option as second-line treatment after FFX failure.

The strength of our study is its large population and the rigorous methodological efforts to assess the effect of Nab-paclitaxel despite its retrospective nature. To our knowledge, this is the largest study reporting second-line treatment outcome with Gem-based regimen after FFX failure, and the first to directly compare Gem and Gem-Nab in a selected population. Another real-life small cohort of patients treated with Gem-based regimen after FFX in Canada found that Gem-Nab was a significant prognostic factor for survival, but the inclusion of non-selected patients combined with the lack of adjustment hinders us from appreciating the direct benefit of Gem-Nab in comparison with Gem alone [21].

Some limitations of the study can be noted. Data were collected on patients’ files and decisions on treatment discontinuation and dose reductions were left to the physician’s discretion. As a result, however, our results may better reflect treatment administration in real-life settings.

There are also some limitations caused by the retrospective feature of our study, such as the absence of randomisation, which may have led to an imbalance in some parameters between the two groups. Moreover, we included patients over a long period of time (>10 years) resulting in a probable time effect, since Nab-paclitaxel was not available at the time of data collection in the Gem group and patients receiving Gem-Nab and patients receiving Gem alone were included in different centres with local specificities. Our methodology aimed to limit selection bias. Firstly, all patients were highly selected since all patients received FFX as first-line treatment and, therefore, the study excluded frailer patients at baseline. Secondly, we used exclusion criteria (abnormal bilirubin levels, extreme age >80 and PS > 2) to exclude, even from the Gem group, patients who might not be fit enough to receive Gem-Nab. We only included patients fit for Gem-Nab in each centre. In the Gem group, these patients were still fit for Gem-Nab but received Gem because of Nab-paclitaxel unavailability. Therefore, patients receiving Gem alone in a centre, where Nab-paclitaxel was available were excluded to reduce selection bias. Furthermore, we performed subgroup analysis and multivariate analysis using Cox regression to limit these biases.

A Phase III prospective trial is currently ongoing and could possibly confirm our findings in a second-line setting with taxane-based chemotherapy after FFX failure. This GEMPAX trial (NCT03943667) aims to evaluate whether the combination of Gem-Nab improves overall survival compared to Gem alone in patients with metastatic ductal adenocarcinoma after FFX failure.

Conclusions

With an improvement in median OS, PFS and DCR, Gem-Nab compared to Gem alone appears to be an effective and safe option as second-line treatment after FFX failure in patients with mPA. Toxicity is more frequent but appears acceptable and manageable despite a higher occurrence of peripheral neuropathy, neutropenia and fatigue. These findings would need to be confirmed by a randomised prospective trial.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank all investigators of the AGEO (Association des Gastro-Entérologues Oncologues) group for their support and participation to this project. Presented in part as a poster discussion at the World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer 2020 (Barcelona, Spain).

Author contributions

Conception/design of the work: SZ, JT and SP. Acquisition of the data: SZ, VH, AL, DT, MS, MG, JW, JE, PA, DB, CM, AD, JT and SP. Analysis of the data: SZ, VH, EA, JT and SP. Interpretation of the data: SZ, VH, EA, JT and SP. Drafting the work: SZ, VH, EA, JT and SP. Revising it critically: all. Final approval of the version to be published: all.

Funding

None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All patients alive at the time of data collection were informed before being enrolled in this study by written information. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The collection and the treatment of the data were conducted according to the MR 004 authorisation, registered at the Commission National Informatique et Liberté (CNIL).

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

SZ, MS, MG, JW, DB, CM and AD declare no competing interests. V. Hautefeuille: lectures: AAA, Novartis, Ipsen, Amgen, Merck, Sanofi. Advisory for AAA, Novartis, Ipsen, Amgen, Merci, Sanofi. Travel support: AAA, Novartis, Ipsen, Amgen, Pfizer, Servier. E Auclin: travel expenses: Mundipharma. Lectures and educational activities: Sanofi Genzymes. A. Lièvre: honoraria for lectures from AAA, Amgen, Bayer, BMS, HalioDx, Incyte, Ipsen, Merck, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi and Servier and for consulting/advisory relationship from AAA, Amgen, Bayer, Incyte, Ipsen, Merck, Novartis Pierre Fabre, Sandoz and Servier. Travel (or subscription to congress) support from AAA, Bayer, Ipsen, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and Servier. D. Tougeron: honoraria from AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, IPSEN, MERCK, MSD, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Amgen, Pierre Fabre. J Edeline: honoraria from Roche, Bayer, Ipsen, MSD, BMS, Eisai, Boston Scientific, AstraZeneca. P. Artru: honoraria as a speaker and/or in an advisory role from Roche Genentech, Servier, Pierre Fabre, Amgen, Merck and Bayer. J Taieb: honoraria as a speaker and/or in an advisory role from Merck KGaA, Sanofi, Roche Genentech, MSD, Lilly, AstraZeneca, Servier, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, HallioDx and Amgen. S Pernot: SP declares honoraria for the speaker or advisory roles for Amgen, Roche, Merck KGaA, Servier, Sanofi, Pierre Fabre, AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article the author name Sonia Zaibet was incorrectly written as Simon Zaibet. The original article has been corrected.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/11/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41416-022-01734-5

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-022-01713-w.

References

- 1.Quante AS, Ming C, Rottmann M, Engel J, Boeck S, Heinemann V, et al. Projections of cancer incidence and cancer-related deaths in Germany by 2020 and 2030. Cancer Med. 2016;5:2649–56. doi: 10.1002/cam4.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud, Yves B, et al. FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N. Engl J Med. 2011;2011:1817–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M, et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine (MPACT Trial) N. Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oettle H, Riess H, Stieler JM, Heil G, Schwaner I, Seraphin J, et al. Second-line oxaliplatin, folinic acid, and fluorouracil versus folinic acid and fluorouracil alone for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer: outcomes from the CONKO-003 trial. JCO. 2014;32:2423–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang-Gillam A, Hubner RA, Siveke JT, Von Hoff DD, Belanger B, de Jong FA, et al. NAPOLI-1 phase 3 study of liposomal irinotecan in metastatic pancreatic cancer: final overall survival analysis and characteristics of long-term survivors. Eur J Cancer. 2019;108:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill S, Ko Y-J, Cripps C, Beaudoin A, Dhesy-Thind S, Zulfiqar M, et al. PANCREOX: a randomized phase III study of fluorouracil/leucovorin with or without oxaliplatin for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer in patients who have received gemcitabine-based chemotherapy. JCO. 2016;34:3914–20. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.68.5776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercadé TM, Chen L-T, Li C-P, Siveke JT, Cunningham D, Bodoky G, et al. Liposomal Irinotecan + 5-FU/LV in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2020;49:14. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000001455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarabi M, Mais L, Oussaid N, Desseigne F. Use of gemcitabine as a second-line treatment following chemotherapy with folfirinox for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2017;13:4917–24. doi: 10.3892/ol.2017.6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilabert M, Chanez B, Rho YS, Giovanini M, Turrini O, Batist G, et al. Evaluation of gemcitabine efficacy after the FOLFIRINOX regimen in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Medicine. 2017;96:e6544. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girardi DM, Faria LDBB, Teixeira MC, Costa FP, Hoff PMG, Fernandes GS. Second-line treatment for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: is there a role for gemcitabine. J Gastrointest Canc. 2019;50:860–6. doi: 10.1007/s12029-018-0166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portal A, Pernot S, Tougeron D, Arbaud C, Bidault AT, de la Fouchardière C, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma after Folfirinox failure: an AGEO prospective multicentre cohort. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:989–95. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burris HA, Moore MJ, Andersen J, Green MR, Rothenberg ML, Modiano MR, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. JCO. 1997;15:2403–13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrillo A, Pappalardo A, Pompella L, Tirino G, Calabrese F, Laterza MM, et al. Nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine as first line therapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients relapsed after gemcitabine adjuvant treatment. Med Oncol. 2019;36:83. doi: 10.1007/s12032-019-1306-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hasegawa R, Okuwaki K, Kida M, Yamauchi H, Kawaguchi Y, Matsumoto T, et al. A clinical trial to assess the feasibility and efficacy of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine for elderly patients with unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2019;24:1574–81. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares HP, Bayraktar S, Blaya M, Lopes G, Merchan J, Macintyre J, et al. A phase II study of capecitabine plus docetaxel in gemcitabine-pretreated metastatic pancreatic cancer patients: CapTere. Cancer Chemother Pharm. 2014;73:839–45. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2414-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo C, Hwang JY, Kim J-E, Kim TW, Lee JS, Park DH, et al. A randomised phase II study of modified FOLFIRI.3 vs modified FOLFOX as second-line therapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1658–63. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaanan A, Trouilloud I, Markoutsaki T, Gauthier M, Dupont-Gossart A-C, Lecomte T, et al. FOLFOX as second-line chemotherapy in patients with pretreated metastatic pancreatic cancer from the FIRGEM study. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:441. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pelzer U, Schwaner I, Stieler J, Adler M, Seraphin J, Dörken B, et al. Best supportive care (BSC) versus oxaliplatin, folinic acid and 5-fluorouracil (OFF) plus BSC in patients for second-line advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III-study from the German CONKO-study group. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1676–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scripture C, Figg W, Sparreboom A. Peripheral neuropathy induced by paclitaxel: recent insights and future perspectives. CN. 2006;4:165–72. doi: 10.2174/157015906776359568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yalcin S, Dane F, Oksuzoglu B, Ozdemir NY, Isikdogan A, Ozkan M, et al. Quality of life study of patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma treated with gemcitabine+nab-paclitaxel versus gemcitabine alone: AX-PANC-SY001, a randomized phase-2 study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:259. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-06758-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang ES, Spratlin J, Cheung WY, Kim CA, Kong S, Xu Y, et al. Real-world outcomes among patients treated with gemcitabine-based therapy post-FOLFIRINOX failure in advanced pancreatic cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2019;42:903–8. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.