To the Editor:

Ethiopia’s civil war erupted in November 2020, rendering 70%–80% of health care facilities in the Tigray region dysfunctional.1 At Ayder, Tigray’s flagship tertiary centre, even basic care has become a luxury.

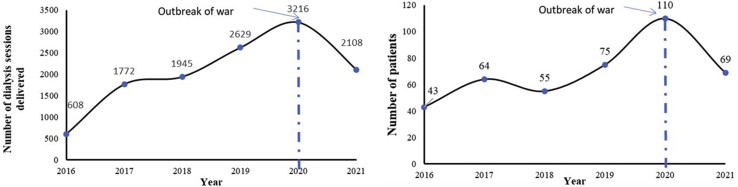

Ayder offers the region’s only hemodialysis facility2 serving 9,000,000 people. War and blockade have caused reduced access, funding and severe supply shortages.3 Dialysis utilization has been drastically curtailed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Total annual number of dialysis sessions (left) and number of patients treated with hemodialysis (right) in consecutive years, per year: 2016 to 2021, Ayder Hospital, Mekelle, Tigray, Ethiopia.

Patients with treatable illnesses are dying. Overall, mortality in patients receiving hemodialysis increased from 25.5% (28 of 110 patients) in 2020 to 53.1% (43 of 81 patients) in 2021. Among the dying are chronic hemodialysis patients on maintenance and children with acute reversible conditions. Between July 1, 2021, and January 15, 2022, 61 new patients requiring emergency dialysis succumbed (including 36 with acute kidney injury).

Consumables were prevented from reaching Tigray from the capital, Addis Ababa, from July 2021. Consequently, difficult decisions had to be made, including using suboptimal protocols. For example, 300 dialysis sessions (12.5%) entailed using single-use dialyzers for 6 to 8 times. Dialysis frequency was reduced from twice to once weekly or even fortnightly, impairing both quality of treatment and life. Using expired central venous catheters or exchanging dialyzers after patient deaths was among the desperate measures adopted. Now, even these staggering compromises are unsustainable; new patients are simply turned away.

Peritoneal dialysis was improvised using locally prepared fluids, saving a few lives. Currently, even i.v. fluid supplies have run out. Advising patients to stop dialysis and live out their remaining days untreated in hospital or at home is the tragic daily predicament of the trained dialysis team. Witnessing the painful deaths of veteran and new patients has imposed huge psychological burdens on the staff.

Ayder’s hemodialysis service was an outstanding example of sophisticated care in a low-resource environment enabled by private-public partnerships, community engagement, and an ethical commitment to care.2 Service provisions now, however, are acutely jeopardized by conflict.3,4 Ayder is counting down the clock, knowing patients with kidney failure will succumb to slow, bitter, and painful death.

We call upon nephrologists worldwide and relevant international bodies, including the ISN, to appeal to the Ethiopian Government to lift the blockade, re-establish supply chains, and restore health care, including the right to dialysis for the people of Tigray.

References

- 1.Gesesew H., Berhane K., Siraj E., et al. The impact of war on the health system of the Tigray region in Ethiopia: an assessment. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paltiel O., Berhe E., Aberha A., Tequare M., Balabanova D. A public–private partnership for dialysis provision in Ethiopia: a model for high-cost care in low-resource settings. Health Policy Plan. 2020;35:1262–1267. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyer O. Tigray’s hospitals lack necessities as relief supplies are blocked, say doctors. BMJ. 2022;376:o34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paltiel O., Clarfield A.M. Tigray: the challenges of providing care in unimaginable conditions. BMJ. 2022;376:o400. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]