Abstract

Proline iminopeptidase produced by Propionibacterium shermanii plays an essential role in the flavor development of Swiss-type cheeses. The enzyme (Pip) was purified and characterized, and the gene (pip) was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli and Lactococcus lactis, the latter species being an extensively studied, primary cheese starter culture that is less fastidious in its growth condition requirements than P. shermanii. The levels of expression of the pip gene could be enhanced with a factor 3 to 5 by using a strong constitutive promoter in L. lactis or the inducible tac promoter in E. coli. Stable replication of the rolling-circle replicating (rcr) plasmid, used to express pip in L. lactis, could only be obtained by providing the repA gene in trans. Upon the integration of pip, clear gene dosage effects were observed and stable multicopy integrants could be maintained upon growth under the selective pressure of sucrose. The multicopy integrants demonstrated a high degree of stability in the presence of glucose. This study examines the possibilities to overexpress genes that play an important role in food fermentation processes and shows a variety of options to obtain stable food-grade expression of such genes in L. lactis.

The proteolytic and peptidolytic processes that occur during the ripening of cheese are of paramount importance for flavor and texture development. The well-balanced process of casein degradation is caused by the combined action of rennet, proteases present in the milk, and the proteases and peptidases produced by the lactic acid bacteria added as starter cultures. Lactococci are used as primary starter cultures in a wide variety of cheeses and, consequently, recent focus on cheese ripening has been on elucidating the proteolytic system of these microorganisms (for reviews, see references 18, 20, and 44). Several proteases and a large number of peptidases have been isolated and analyzed, their genes have been cloned and sequenced, and their respective contributions to the complex cheese-ripening process are being determined (19, 20).

In some cheeses, especially Swiss-type cheeses, propionibacteria are added as a secondary starter culture. These microorganisms ferment residual sugar and lactate to propionic acid. They are also responsible for the typical sweet flavor of these cheeses, mainly by the action of a proline iminopeptidase (Pip) that cleaves amino-terminal proline residues from peptides (21, 31). Moreover, since proline-containing peptides are known to cause bitterness (15), Pip most probably has a debittering effect during cheese ripening. Pip activity of Propionibacterium shermanii, the secondary starter preferably used, is rather low, and growth of the strictly anaerobic microorganism is slow. Consequently, overproduction of Pip in a food-compatible way by a lactic acid bacterium, which is less fastidious in its growth conditions, might enhance the processes of cheese ripening and debittering.

A large variety of genetic tools and techniques have been developed for lactococci, enabling selective modification of these microorganisms, which might ultimately lead to a better control of the complex cheese-ripening processes (18). Recently, it has become possible to use genetically modified lactococci in foods by the development of food-grade lactococcal plasmids, by employing metabolic genes or genes conferring natural resistance to antimicrobial agents as selectable markers (9, 10, 14, 34). Furthermore, chromosomal gene replacement systems are available which eliminate the need for a selectable marker in the modified strain (4, 24, 27, 28). We recently developed a system which has the potential to integrate multiple copies of the gene of interest in the lactococcal chromosome and to enhance and stabilize the food-grade expression of genes (23). This system is based on the conditional replication of a Lactococcus lactis pWV01 derivative and uses the sucrose genes of Pediococcus pentosaceus as selectable genes.

We describe here the purification and characterization of the proline iminopeptidase (Pip) of P. shermanii ATCC 9617 and the isolation and nucleotide sequence of the pip gene. Also, the expression of the gene in Escherichia coli and its stable multiple copy insertion in a food-compatible manner into the chromosome of L. lactis are described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. E. coli was grown in TY medium (35) or Luria broth (LB), and L. lactis was grown in M17 medium (38) containing 0.5% glucose (GM17). P. shermanii ATCC 9617 was cultivated at 30°C under anaerobic conditions in sodium lactate broth (sodium lactate, 1%; Trypticase-peptone, 1%; K2HPO4, 0.025%; MnSO4, 0.0005%; and yeast extract, 1%; the pH was adjusted to 7.0). L. lactis cells were plated onto GM17 agar plates containing 0.3 M sucrose after electrotransformation. Glucose was omitted when colonies were selected for their ability to ferment sucrose. Kanamycin (Km) was used at a final concentration of 30 μg/ml for E. coli. Erythromycin (Em) was used at final concentrations of 100 and 5 μg/ml for E. coli and L. lactis, respectively. Chloramphenicol (Cm) was used at a final concentration of 5 μg/ml for L. lactis.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant properties | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli | ||

| NM522 | supE thi lac-proAB hsd5(r−, m−)[F′ proAAB lacIqZΔM15] | Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.) |

| EC101 | RepA+ JM101 45, Kmr, carrying a single copy of pWV01 repA in glgB | 22 |

| L. lactis | ||

| MG1363 | Plasmid-free NCDO712 | 12 |

| MG1363(pLP712) | MG1363 carrying plasmid pLP712, Lac+ Prt+ | Laboratory collection |

| LB250 | MG1363 carrying a single copy of the lac operon 8 downstream of ORF1 of the pepX gene region (30) | This work |

| LL108 | RepA+ MG1363, Cmr, carrying multiple copies of pWV01 repA in chromosomal fragment A (26) | 23 |

| LL302 | RepA+ MG1363, PepX−, carrying a single copy of pWV01 repA in pepX | 23 |

| UG139 | MG1363(pLP712), Suc+ Pip+, carrying chromosomally amplified pUG139 | This work |

| UG239 | MG1363, Suc+ Pip+, carrying chromosomally amplified pUG239 | This work |

| UG339 | MG1363(pLP712), Pip+/− PepX−, carrying one copy of pip obtained by replacement recombination with pUG339 | This work |

| UG439 | MG1363(pLP712), Pip+/−, carrying one copy of pip obtained by replacement recombination with pUG439 | This work |

| UG2539 | LB250, Pip+/−, carrying one copy of pip obtained by replacement recombination with pUG539 | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMG36E | Emr, pWV01 origin, expression vector for L. lactis | 42 |

| pUR5302 | Apr, pBR322, carrying a 10-kb insert of P. shermanii DNA containing pip | This work |

| pMMB67EH | Apr, tac expression vector for E. coli | 11 |

| pUR5303 | Apr, pMMB67EH carrying pip of P. shermanii | This work |

| pUG37 | Emr, pMG36E carrying the 3′ end of pip in the SacI and XbaI sites | This work |

| pUG38 | Emr, pUG37 with a 193-bp deletion downstream of pip | This work |

| pUG39 | Emr, pUG38 carrying the complete pip gene under control of the transcription and translation signals of ORF32 | This work |

| pORI28 | Emr, ori+ of pWV01, RepA−, replicates only in strains providing repA in trans | 24 |

| pINT29 | Emr, ori+ of pWV01, RepA−, specific for replacement integration in pepX | 23 |

| pINT51 | Emr, ori+ of pWV01, RepA− LacZ+, specific for replacement integration in strain LB250 | This work |

| pINT61 | Emr, ori+ of pWV01, RepA− LacZ+, specific for replacement integration downstream of ORF1 in the pepX locus | This work |

| pINT124 | Suc+, specific for SCO integration in pepX | 23 |

| pINT125 | Suc+, specific for SCO integration in pepX | 23 |

| pINT250 | Emr Lac+ LacZ+, derivative of pINT61 | This work |

| pUG139 | Suc+ Pip+, derivative of pINT124 | This work |

| pUG239 | Suc+ Pip+, derivative of pINT125 | This work |

| pUG339 | Emr Pip+ LacZ+, derivative of pINT29 | This work |

| pUG439 | Emr Pip+ LacZ+, derivative of pINT61 | This work |

| pUG539 | Emr Pip+ LacZ+, derivative of pINT51 | This work |

Transformation.

E. coli and L. lactis were transformed by electrotransformation as described before (13, 47). E. coli was also transformed by using cells made competent with CaCl2.

Isolation of Pip.

A 150-liter culture of P. shermanii was harvested at the late logarithmic phase, concentrated to 2 liters in a continuous disc centrifuge (Westfalia SA1; Westfalia, Northvale, N.J.), washed three times with 0.5 M NaCl at 15°C, and resuspended in 20% sucrose at 4°C for 2 h. Cells were lysed after centrifugation by resuspending them in 3 liters of lysis buffer (0.01 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.8; 0.5 M sucrose; 0.3 M NaCl; 0.05 M MgSO4; 0.01 M KCl; 2 mg of lysozyme per ml) and incubating them for 8 h at room temperature. Spheroplasts were recovered by centrifugation (60 min at 8,000 × g) and lysed by resuspending them in 5 liters of a 5 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), followed by incubation for 4 h at room temperature. A cell extract was obtained by the elimination of intact cells and the cell debris through centrifugation for 1 h at 12,500 × g. The crude cell extract was adjusted to 15% (NH4)2SO4 saturation by slowly adding solid (NH4)2SO4 at 0°C. The precipitate was removed by centrifugation (30 min at 12,500 × g), and (NH4)2SO4 was added to the supernatant to achieve 45% saturation. The precipitate was again collected by centrifugation, dissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and dialyzed against this buffer for 48 h at 4°C. The dissolved precipitate was fractionated by ion-exchange chromatography on a Q-Sepharose Fast Flow anion-exchange column (XK 50/20; Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) equilibrated with the same buffer. The enzyme was eluted with a linear gradient of 0.1 to 0.5 M NaCl. The fractions containing Pip activity were pooled, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and concentrated to 40 ml by ultrafiltration (Amicon PM10; Amicon, Beverly, Mass.). Ion-exchange chromatography was repeated, and the enzyme was subsequently eluted with a gradient of 0.2 to 0.5 M NaCl. Pip containing fractions were concentrated to 20 ml. The enzyme was purified further on a Superdex-200 Biopilot column (Pharmacia) equilibrated with 0.5 M NaCl in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0). Pip-containing fractions were collected, dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), and concentrated. Finally, the enzyme was purified by anion-exchange chromatography on a Mono Q (HR 5/5) column equilibrated with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0). Bound activity was eluted by a 0.3 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient in the same buffer. Enzyme activity during purification was measured at room temperature by using 1 mM proline–para-nitroanilide substrate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The release of p-nitroaniline was monitored at 405 nm for 5 min with a Shimadzu UV-240 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Tokyo, Japan). One aminopeptidase unit is defined as the amount of enzyme producing 1 μmol of p-nitroaniline per min (ε405 pNA = 9,620 M−1 · cm−1).

Protein and protein sequence analysis.

Protein concentrations were determined by using the Pierce bicinchoninic protein assay reagent (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard (37). Molecular weights were determined by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) on a 8 to 18% gradient gel under reducing conditions. The amino acid sequence of Pip was determined on the Applied Biosystems 470A gas-phase sequencer equipped with an online type 120A PTH analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, Calif.).

Enzyme characterization.

The effect of pH on Pip enzyme activity on proline–p-nitroanilide was determined for pH values ranging from 5.0 to 10.0 with 0.5 pH unit intervals in 40 mM Britton-Robinson buffer (33) at room temperature. The effect of temperature on Pip was measured in a range of 25 to 60°C in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). After 10 min of incubation, the reaction was stopped by the addition of glacial acetic acid, after which the A405 was determined. The effect of chemical reagents was tested by incubating Pip for 60 min at 4°C in 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with the reagents at the concentrations indicated in Table 2; the substrate was then added, and the activity was measured.

TABLE 2.

Effects of various chemical reagents on Pip activity

| Chemical reagent | Concn (mM) | Relative activity (%) |

|---|---|---|

| DTT | 1 | 89 |

| β-Mercaptoethanol | 1 | 100 |

| Iodoacetamide | 1 | 93 |

| EDTA | 10 | 40 |

| 1,10-Phenanthroline | 1 | 74 |

| PMSF | 1 | 63 |

| Bestatin | 1 | 89 |

Cloning of pip.

P. shermanii ATCC 9617 was grown in 100 ml of sodium lactate broth for 36 h at 30°C. Cells were collected by centrifugation and resuspended in 12 ml of Tris-sucrose buffer (6.7% sucrose; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA). Then, 3 ml of 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)–100 mg of lysozyme per ml was added, and the mixture was incubated for 30 min at 37°C. Proteins were digested by adding 750 μl of a 10-mg/ml concentration of pronase E for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were lysed completely by adding 1.5 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl–0.25 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and 900 μl of 20% SDS, followed by incubation for 10 min at 37°C. Proteins were separated from DNA by a twofold extraction with phenol-chloroform. DNA was precipitated from the water phase with 2 volumes of ethanol and then collected on a glass rod, dried, and dissolved in buffer. DNA (150 μg) was then partially digested with Sau3A to yield DNA with a mean molecular weight of 5 to 10 kb. The digested DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform, precipitated with 2 volumes of ethanol, dissolved, and size separated on a 10 to 40% sucrose density gradient as described by Maniatis et al. (29). Fractions containing DNA with a molecular weight of about 5 kb were pooled, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol. A clone bank was made by ligating this DNA fraction in the BamHI site of pBR322 and using it to transform competent E. coli 294 cells. The clonebank was screened by hybridization with a mixed DNA probe (AC[A/T] TGG CA[A/G] CAT [A/T][C/G][A/C/T] AT[C/T] CC) derived from the first seven amino acids of the Pip protein. The mixed probe was synthesized by using an Applied Biosystems 380A DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems). The probe was radioactively labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP, both of which were obtained from Amersham (Amersham International, Amersham, United Kingdom), and hybridized to 1,500 colonies of the bank lysed in situ. After autoradiography, plasmids from hybridizing clones were isolated.

Construction of plasmids.

A PCR fragment of pip was generated on pUR5302 by using the primer pip200 (5′-GGA ATT CAT GAC ATG GCA GCA CAG TAT), which is complementary to nucleotides 503 to 523 and is extended with an EcoRI site, and the primer pip203 (5′-CCA GGG AGC GGA TCC GTG AGG GCC), which is complementary to nucleotides 1174 to 1197. The 700-bp fragment was digested with EcoRI and PvuI, ligated to the PvuI-PvuII fragment of pUR5302, and inserted into EcoRI-SmaI-digested tac expression vector pMMB67EH (11), resulting in pUR5303. Expression of pip was induced by the addition of 0.4 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) to E. coli JM109(pUR5303) cells grown in 100 ml of Luria broth to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.5. Cells were grown for another 1.5 h, harvested by centrifugation, washed in 20 ml of 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), and resuspended in 20 ml of the same buffer. To 5 ml of this suspension 3 g of glass beads (0.15 mm in diameter; Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) was added, and the mixture was sonicated six times for 30 s in a Soniprep 150 (MSE Ltd., Crawley, Sussex, United Kingdom) by using a small tip. After elimination of the cell debris by centrifugation, the Pip activity in the supernatant was determined.

For the expression of the P. shermanii pip gene in L. lactis, the 3′-end of the gene was cloned as a SacI-XbaI fragment from pUR5303 into the SacI-XbaI sites of pMG36e, resulting in plasmid pUG37. A small region downstream of pip was deleted to remove a number of restriction enzyme sites by digesting pUG37 with StyI and HindIII and treatment with Klenow enzyme to create blunt ends and religation. In the SacI site of the resulting plasmid, pUG38, the 5′ end of pip was inserted as a SacI fragment generated by PCR with primers pip210 (5′-ATA AGA GCT CGA GAA TAT TCG GAG GAA TTT TGA AAT GAC ATG GCA GCA CAG TAT CC) and pip203, thus creating pUG39.

Chromosomal integrations.

Amplified integrated plasmid copies carrying pip were selected by the ability of the transformants to grow on medium with sucrose as the only carbon source (23). Insertion of pip and the lac operon by double crossover recombination into the L. lactis chromosome was done as described earlier (24).

Construction of a Lac+ L. lactis strain.

To obtain an L. lactis strain with a copy of the lactococcal lac operon integrated at a defined chromosomal locus, plasmid pINT250 was used. First, pINT61, which is a derivative of pORI280, a vector designed for use in gene replacement strategies, was constructed (24). Plasmid pINT61 contains a 3-kb XbaI lactococcal chromosomal fragment with a multiple cloning site (MCS) engineered approximately in the middle of the fragment. The MCS is located just downstream of the putative terminator of ORF1 in the pepX locus. The entire lac operon (lacRABCDEFG; EMBL databank accession number J05748) was cloned in the MCS of pINT61, resulting in plasmid pINT250. Plasmid pINT250 was used to transform strain MG1363; transformants were selected on M17 agar medium containing lactose as the only carbon source. Subsequently, transformants were screened for the absence of Emr and LacZ markers. A transformant with a chromosomal structure as shown in Fig. 3 was isolated and designated LB250. A derivative of pORI280, which is specific for integration in strain LB250, was constructed. The vector carries a 0.6-kb fragment with the 3′ end of ORF1 and a 0.5-kb fragment with 3′ end of lacR, which serve as homologies for recombination with the chromosome. An MCS is present between the ORF1 and the lacR fragments such that genes of interest can be inserted into the chromosome of strain LB250 by double-crossover recombination (see Fig. 3).

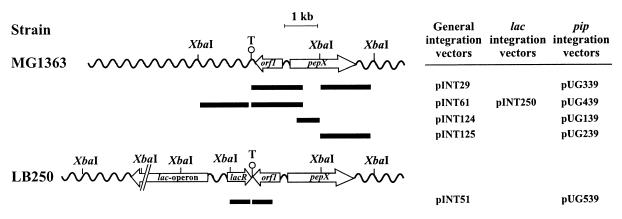

FIG. 3.

Schematic presentation of the location on the lactococcal chromosome of the chromosomal DNA fragments used for integration (black boxes). The black boxes represent the chromosomal fragments present in the indicated integration vectors. In the DCO vectors pINT29, pINT51, and pINT61 containing two chromosomal fragments the pip gene was cloned in between the adjacent chromosomal fragments. Wavy lines, chromosomal DNA; T, transcriptional terminator; pepX, PepX gene; orf1, open reading frame encoding polypeptide with unknown function; lacR, repressor gene of the lac operon. The interrupted leftward arrow is the L. lactis lacABCDEFG operon.

Bioassays.

The ability of L. lactis colonies to ferment sucrose (Suc+) or lactose (Lac+) was tested by direct plating of cells or streaking of colonies onto M17 agar plates containing 0.5% sucrose or 0.5% lactose, respectively, and 0.005% bromocresol purple (BCP) as a pH indicator. Suc+ or Lac+ colonies stain yellow on these plates, whereas Suc− or Lac− colonies remain white. Proteinase-proficient strains (Prt+) were identified on plates treated with citrate milk agar (10% skim milk, 0.75% sodium citrate [pH 6.8]) containing 0.005% BCP. Prt+ strains form large yellow colonies on these plates in contrast to the small white colonies of Prt− strains. X-prolyldipeptidyl amino peptidase (PepX)-deficient strains were identified by using a PepX plate assay as described before (27). Pip-proficient strains were identified by a modified PepX plate assay. Proline–β-naphtylamide was dissolved in 50% ethanol and was carefully spread onto the top agarose layer, followed by an incubation of 5 min at room temperature. Subsequently, a solution of Fast Garnet GBC base (Sigma) was spread onto the plates. Pip+ colonies stain red within a few minutes, and Pip− colonies remain white. L. lactis strain MG1363 is Pip− in these assays.

Heterologous Pip activity assay.

Cell extracts of L. lactis were prepared as described by van de Guchte et al. (40). Appropriate dilutions of cell extracts (50:1) were mixed with a 200:1 dilution assay buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7; 2 mM proline–para-naphtylamide) and then incubated at room temperature. The OD405 was measured for 10 min with a ThermoMax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Menlo Park, Calif.). The protein content of the lysates was determined according to the method of Bradford (5). The Pip activity was calculated in arbitrary units (AU; 1 AU = OD405/min/mg of protein). In L. lactis strain MG1363 the Pip activity is less than 0.01 AU.

Plasmid stability assay.

Overnight cultures of strains UG139 and 239 cultured in SM17 and strains UG339, 439, and 2539 cultured in GM17 medium (t [in generations] = 0) were diluted to 103 CFU/ml of GM17 and grown to the stationary phase, which requires approximately 20 generations. Three identical transfers in GM17 medium were carried out to reach 80 generations of nonselective growth (t = 80). At t = 0 and t = 80, dilutions of the UG139 and UG239 cultures were plated on SM17 medium containing 0.005% BCP to determine the Suc phenotype of over 1,000 CFU for each strain. The Lac phenotype of strains UG139, 339, 439, and 539 was analyzed by plating on LM17 with 0.005% BCP, and the Prt phenotype of strains UG139, 339, and 439 was determined by plating on citrate milk agar plates with 0.005% BCP. Chromosomal DNA of all cultures was isolated at t = 0 and t = 80 for Southern blot analysis.

DNA isolation and analysis.

Chromosomal DNA was isolated as previously described (26). Plasmid DNA was extracted according to the method of Birnboim and Doly (3) with minor modifications. L. lactis cells were incubated with lysozyme for 10 min at 50°C to obtain optimal lysis. Large-scale plasmid isolations, carried out by using CsCl density gradients and restriction enzyme incubations of plasmid and chromosomal DNA, were done according to Maniatis et al. (29). DNA transfer to Qiabrane Nylon Plus membranes (Qiagen, Düsseldorf, Germany) was done according to the protocol of Chomczynski and Qasba (6). Probes were labeled by using the ECL Labeling Kit, and the hybridization conditions and probe detection procedure were according to the instructions of the ECL system manufacturer (Amersham International).

Determination of the number of integrated plasmid copies.

The number of integrated plasmid copies in strains UG139 and UG239 was determined by using Southern blots with membranes containing dilutions of the chromosomal DNA of these strains and the chromosomal DNA of strain MG129 containing a single copy of the sucrose genes in its chromosome (23). The dilution rates were determined by using the single-copy chromosomal fragment A (26) as a probe. A PvuII fragment containing scrA and scrB was used as a probe to determine the copy number. A Pharmacia LKB2222-020 UltraScan XL laser densitometer (Pharmacia) was used to measure the intensity of the hybridizing fragments.

Nucleotide sequence analysis and data handling.

DNA sequences were determined on purified double-stranded plasmid DNA essentially according to the Sanger dideoxy chain termination procedure. DNA sequence analysis, sequence alignment, and sequence database searching were conducted with programs contained within the Sequence Analysis Software Package (version 6.1) licensed from the Genetics Computer Group (University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wis.) (7). The predicted amino acid sequences were compared by the algorithm of Pearson and Lipman (32) (FASTA) with proteins in the SWISS-PROT protein sequence database.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence was submitted to the EMBL databank (Heidelberg, Germany) and was given the accession number AJ001361.

RESULTS

Purification and characterization of Pip.

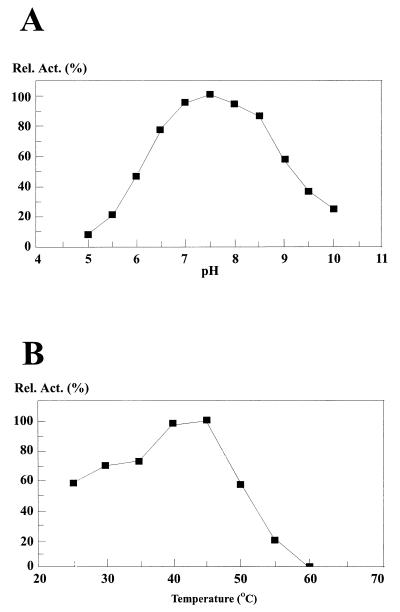

Pip is located intracellularly in P. shermanii (36). Enzymatic treatment was used to isolate Pip from the spheroplasts of cultivated P. shermanii cells. This method minimizes contamination with proteases and other peptidases. Pip was purified in five steps as described in detail in Materials and Methods. After the final ion-exchange chromatography step, the enzyme was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The sample showed one single protein with an estimated molecular mass of 54 kDa (not shown). Based on its enzyme activity on proline–p-nitroanilide, the enzyme was purified 970-fold, with a yield of 4%. The effect of pH on activity on the same substrate is given in Fig. 1A. The enzyme was shown to be active between pH 5 and 10, with an optimum activity at pH 7.5. At this pH value the optimum temperature was found to be 45°C. The enzyme showed no activity at all at 60°C (Fig. 1B). The effects of various chemical reagents on Pip activity are shown in Table 2. Activity was reduced by 40% by the serine protease inhibitor phenymethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF). The metal-chelating agent EDTA inhibited enzyme activity by 60%, suggesting that the enzyme activity is dependent on the presence of a metal ion. Disulfide reducing agents such as dithiothreitol (DTT) and β-mercaptoethanol, like the sulfydryl-group reagent iodoacetamide, had no inhibitory effect on enzyme activity. From these results it can be concluded that Pip most likely is a metal-dependent serine peptidase.

FIG. 1.

(A) Effect of pH on Pip activity. (B) Effect of temperature on Pip activity.

Isolation of pip and nucleotide sequence analysis.

When subjected to amino acid sequencing, the Pip sample revealed 20 amino-terminal amino acids: TWQHSIPGLMTRSIRVDVPL. From a clone bank of P. shermanii DNA in pBR322, 1,500 colonies were screened by using the mixed probe (see Materials and Methods) derived from the N-terminal end of the enzyme. Six hybridizing colonies contained plasmids with different-sized inserts. All of the inserts contained the same BamHI fragment of about 1 kb. This fragment was subcloned in the BamHI site of pEMBL19 and then sequenced and shown to carry 227 codons of an open reading frame specifying the N-terminal sequence of Pip. The remaining part of pip was sequenced directly on one of the original clones, pUR5302, which contains an insert of more than 10 kb. The complete pip gene turned out to be 1,242 bp long, encoding a putative protein of 414 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of 45,376. No promoter or Shine-Dalgarno sequence similar to those found in E. coli was found upstream of the start codon. After a screening of the database, homologies were found with proline iminopeptidases of Lactobacillus delbrueckii (2), Aeromonas sobria (17), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (1). Homology with Pip of Bacillus coagulans (16) clearly was less extensive. The most extensive homology was found with Pip of A. sobria, with up to 35% identical residues. Several clusters of highly homologous sequences are present, including GXSXGG, an indicator sequence for serine-type peptidases (2).

Expression of pip in E. coli and L. lactis.

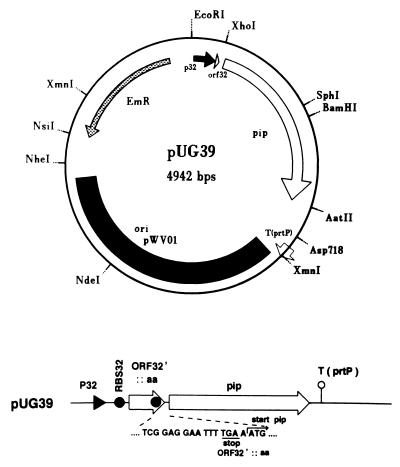

In P. shermanii, pip is present on the chromosome and under the transcriptional control of its native promoter, resulting in a Pip activity level of 4.6 AU. IPTG-induced expression of pip under control of Ptac in E. coli JM109(pUR3503) resulted in a Pip activity level of 29 AU. Since expression of pip in a food-grade microorganism such as L. lactis is a prerequisite for food purposes, pip was cloned downstream of the constitutive P32 promoter (43) in the L. lactis expression vector pMG36e (40), yielding plasmid pUG39 (Fig. 2). Expression of pip in E. coli NM522(pUG39) resulted in a Pip activity level of 3.5 AU. Surprisingly, after transfer of the plasmid to L. lactis strain MG1363, only a low level of Pip activity was measured (0.3 AU). Pip activity was readily lost after an overnight culturing of the strain MG1363(pUG39) in GM17Em medium. Plating assays indicated that over 90% of the Emr colonies were Pip−. Apparently, the presence and/or expression of pip in L. lactis destabilizes pWV01 derivatives but the nature of this instability was not studied further. Plasmid pUG39 was found to be stable in L. lactis strain LL108, which overproduces the pWV01 RepA protein in trans and maintains pWV01 derivatives in 5- to 10-fold-higher copy numbers (23). Pip activity level in LL108(pUG39) was 12.4 AU (Table 3), indicating that high Pip activity levels can be obtained in L. lactis by increasing the gene dosage.

FIG. 2.

Diagram of the pip expression plasmid pUG39, in which pip is under the control of the lactococcal promoter P32 (black arrow). The pip gene is preceded by the truncated ORF32. ORF32 was translationally fused to a number of codons of the multiple cloning site (ORF32′::aa) to create a gene construct that allows translational coupling of pip as shown in the linear presentation of the expression cassette. RBS32 (black dots), ribosome binding site of ORF32; arrow designated T(prtP), terminator of the lactococcal prtP gene; EmR, erythromycin resistance gene. The origin of replication of pWV01 is indicated by the black box.

TABLE 3.

Pip activities of wild-type and recombinant strainsa

| Strain | Pip activity in AUb

|

|

|---|---|---|

| t = 0 | t = 80 | |

| P. shermanii | 4.6 | ND |

| E. coli | ||

| NM522(pUG139) | 3.5 | ND |

| JM109(pUR3503) | 29 | ND |

| L. lactis | ||

| MG1363 | 0.0 | ND |

| MG1363(pUG39) | 0.3 | ND |

| LL108(pUG39) | 12.4 | ND |

| UG139 | 15.7 | 7.1 |

| UG239 | 12.4 | 3.5 |

| UG339 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| UG439 | 0.3 | 0.2 |

| UG2539 | 0.5 | 0.4 |

UG strains were subjected to 80 generations of nonselective growth (t = 80).

1 AU = OD405/min/mg of protein. ND, not done.

In an attempt to increase pip gene expression or to optimize the translation of pip mRNA, several additional constructs were made. The truncated ORF32 in plasmid pUG32 stops one base before the AUG start codon of pip (Fig. 2). This configuration was modified so that the stop and start codons overlap in an AUGA arrangement to optimize possible translational coupling (41). In another plasmid the preceding truncated ORF32 was removed. No significant improvement in the expression of pip was observed in either case, as judged by Pip activity assays on cell extracts (data not shown). Promoter P32 was replaced in two other constructs by the lactococcal promoters P23 and P59, both of which have been reported to contain expression signals stronger than does P32 (43). However, expression of pip by P23 resulted only in low levels of Pip activity in strains MG1363 and LL108. Replacement of P32 by P59 was obstructed by extensive deletion formation of the resulting plasmid in both E. coli and L. lactis (data not shown).

Single-copy and multicopy food-grade integrations of pip.

The expression cassette present in pUG39 was inserted into various integration vectors. The specific locations on the chromosome to which a gene of interest is delivered by these plasmids are summarized in Fig. 3. Three double-crossover (DCO) vectors were used: pUG339, a derivative of pINT29, directs insertion of pip into pepX; pUG439 targets it just downstream of ORF1 in the pepX gene region; and pUG539 is specific for integration in LB250, a strain carrying the entire L. lactis lac operon in its chromosome (see Materials and Methods). Two single-crossover (SCO) vectors, pINT124 and 125, were also used. These vectors carry the sucrose genes of P. pentosaceus as the selectable marker. Selection for the integration event results in multiple-copy integration of the vector in a head-to-tail arrangement (23). The pip gene carrying pINT124 derivative of pUG139 inactivates pepX upon integration, whereas the pINT125 derivative, pUG239, does not (Fig. 3).

Plasmid pUG239 was integrated in the plasmid-free strain MG1363, resulting in strain UG239. Strain MG1363 carrying the lactose-proteinase plasmid pLP712 was used to integrate plasmids pUG139, pUG339, or pUG439. The resulting strains were designated UG139, UG339, and UG439, respectively. Finally, plasmid pUG539 was introduced into strain LB250, after which strain UG2539 was isolated. The phenotypes of the food-grade recombinant UG strains are summarized in Table 4. Strains UG339, UG439, and UG2539 contain one copy of pip in the expected chromosomal location and have lost all other parts of the delivery vectors, as determined by Southern blot analyses (data not shown). Multiple copies of the integration plasmids were detected in Southern blots at the expected chromosomal position in strains UG139 and UG239. Strains UG139 and UG239 contain approximately 26 and 16 copies, respectively, of the integration vectors (data not shown).

TABLE 4.

Relevant characteristics of the recombinant food-grade integrants

| Parental strain | Integration plasmid | Integrant | Phenotypesa

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pip | Suc | Lac | Prt | PepX | |||

| MG1363(pLP712) | pUG139 | UG139 | + | + | + | + | − |

| MG1363 | pUG239 | UG239 | + | + | − | − | + |

| MG1363(pLP712) | pUG339 | UG339 | ± | − | + | + | − |

| MG1363(pLP712) | pUG439 | UG439 | ± | − | + | + | + |

| LB250 | pUG539 | UG2539 | ± | − | + | − | + |

Phenotypes were determined by using specific plate assays (see Materials and Methods). +, Colonies demonstrated clear activity or were able to ferment the indicated carbon source; ±, weak activity; −, no activity or inability to ferment the indicated carbon source.

Low Pip activity levels were measured in the strains containing one integrated copy of pip: 0.3 to 0.5 AU in strains UG339, UG439, and UG2539. High levels of Pip activity were present in the multicopy strains UG139 (15.7 AU) and UG239 (12.4 AU), showing once again a clear gene dosage effect. The latter activities are three- to fourfold higher than those in P. shermanii (Table 3).

Stability under nonselective growth conditions.

Strains UG339, UG439, and UG2539 lack a selectable marker and can therefore only be cultivated under nonselective growth conditions. After 80 generations these strains had retained their low level of Pip activity, as expected (Table 3). The Suc and Pip phenotypes of strains UG139 and UG239 were stable when the strains were grown in selective M17 medium containing sucrose, as judged by plating assays (data not shown). When cultured in nonselective GM17 medium for 80 generations, strains UG139 and UG239 retained 45 and 28%, respectively, of their Pip activity (Table 3). This was caused by a decrease in the average number of integrated plasmid copies in both strains. Southern blot analysis revealed a decrease of from 26 to 16 copies for strain UG139 and from 16 to 4 copies for strain UG239 (data not shown). Colonies of both strains at t = 80 stained light to dark red in the Pip activity plate assay, indicating low and high Pip activities, respectively. Over 99.5% of these colonies have retained their ability to ferment sucrose, indicating that the loss of integrated plasmid copies is most likely a gradual process with differences per cell in the rate of loss. Notwithstanding the slow decrease in the number of integrated plasmid copies of approximately 0.1 copy per generation, the culture of strain UG139 still exhibits after 80 generations of nonselective growth a 1.5-fold-higher Pip activity than does P. shermanii (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In the present report we describe the isolation and characterization of proline iminopeptidase (Pip) of P. shermanii ATCC 9617 and the cloning of the corresponding gene. Moreover, the construction of food-grade modified L. lactis strains that overexpress Pip and the comparison with Pip overexpression in E. coli are also described. The results of the enzyme inhibition studies were comparable to those reported by Panon (31). Pip is only partially inhibited by some of the inhibitors used. One explanation for incomplete inhibition by these reagents would be the presence of another proline iminopeptidase activity, one that is not a metal-dependent serine peptidase. Based on SDS-PAGE and the fact that only one amino acid sequence was found, the presence of a contaminating second enzyme is considered to be very unlikely. It is well known that the effectiveness of enzyme inhibitors significantly differs between various enzymes and that inhibitors such as PMSF are not very stable in an aqueous solution. More-extensive studies at higher reagent concentrations are needed to unequivocally determine the inhibitory effects on this peptidase.

The enzyme shows homologies with proline iminopeptidases characterized before. Surprisingly, the most extensive homology was found with Pip of A. sobria and not with Pip of the more related gram-positive species L. delbrueckii or B. coagulans. The low overall homology with the Pip of B. coagulans can be explained by the fact that this Pip is not a serine peptidase (46). This is confirmed by the fact that no GXSXGG serine peptidase consensus sequence was found in B. coagulans Pip (2). Our biochemical data and the presence of this consensus sequence in the Pip of P. shermanii confirm that this proline iminopeptidase belongs to the class of serine peptidases. The relatively low homology to Pip of L. delbrueckii may be explained by the suggestion of Kitazono et al. (17) that there may be two groups of proline aminopeptidases. One group, containing the Aeromonas enzyme, consists of large multimeric enzymes of around 200 kDa, while the other, containing the Bacillus, Neisseria, and Lactobacillus enzymes, consists of smaller, mostly monomeric enzymes. Based on our sequence comparisons alone, the Propionibacterium enzyme belongs to the Aeromonas class of proline iminopeptidases. However, the enzyme purified from the Propionibacterium class had a much smaller molecular mass on SDS-PAGE gels. Unfortunately, no further biochemical data are available for the other proline iminopeptidases belonging to the Aeromonas class of enzymes.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study describing the stable chromosomal integration in L. lactis of multiple copies of an industrially relevant heterologous gene in a food-compatible manner. Although Ptac-driven expression of pip in E. coli is higher than expression in L. lactis when the constitutive P32 promoter is used, a comparable expression level was obtained in L. lactis behind the constitutive P32 promoter when a replication system which generates a high plasmid copy number is used. In this way, both species showed three- to fivefold-higher Pip activity levels than the original strain of P. shermanii.

A pip gene dosage effect was observed when the single-copy and multiple-copy L. lactis strains were compared, although it was not a linear correlation. While such a phenomenon has been observed before in L. lactis (25, 39), a linear correlation has been described as well (39). There is also a difference in Pip activity between strains carrying approximately the same number of pip genes. Strain UG139 had 16 copies of the gene after 80 generations of nonselective growth with a concomitant Pip activity level of 7.1 AU, while an activity level of 12.4 AU was measured in strain UG239, which also carried 16 copies of the pip gene. At present we do not have an explanation for these discrepancies. Specific advantages and disadvantages of the food-grade integration systems used in this study compared to other food-grade vector systems have been discussed elsewhere (23).

The nature of the instability of autonomously replicating pWV01-derived vectors carrying pip remains a subject of speculation, but it may be that the high GC content of pip (67%) interfered with optimal plasmid replication. The observed plasmid stabilization by the in trans overproduction of the plasmid replication initiation protein is an interesting option for stabilizing rolling circle-type plasmids, and it may provide an attractive alternative for constructing stable, autonomously replicating food-grade vector systems.

Although the strains carrying multiple pip copies produced approximately 40-fold more active Pip than the single-copy pip strains, it is presently unknown whether the expression level obtained in strain UG139 constitutes the upper limit of pip expression in lactococci. P32 is not the strongest lactococcal promoter known to date, but the difficulties encountered in using the stronger lactococcal consensus promoters P23 and P59 indicate that inducible gene expression systems are to be preferred in future attempts to achieve higher pip expression levels. Nevertheless, with the present integration system a set of food-grade lactococcal strains were obtained with attractive properties. The strains differ in a number of peptidolytic activities, namely, high or low Pip activity in the presence or absence of PepX and/or PrtP, permitting the study of flavor development in milk fermentations or in other food-related processes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by CEC VALUE Program, contract number BAP0012NL. Jan Kok is the recipient of a fellowship of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

We thank Jan Kuiper and Rob van der Velden for the Propionibacterium fermentations, and Han van Brouwershaven for amino acid sequencing.

REFERENCES

- 1.Albertson N H, Koomey M. Molecular cloning and characterization of a proline iminopeptidase from Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:1203–1211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlan D, Gilbert C, Blanc B, Portalier R. Cloning, sequencing and characterization of the pepIP gene encoding a proline iminopeptidase from Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus CNRZ 397. Microbiology. 1994;140:527–535. doi: 10.1099/00221287-140-3-527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biswas I, Gruss A, Ehrlich S D, Maguin E. High-efficiency inactivation and replacement system for gram-positive bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3628–3635. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3628-3635.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantification of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomczynski P, Qasba P K. Alkaline transfer of DNA to plastic membrane. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;122:340–344. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programmes for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Vos W M, Boerrigter I, van Rooijen R J, Reiche B, Hengstenberg W. Characterization of the lactose-specific enzymes of the phosphotransferase system in Lactococcus lactis. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:22554–22560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Vos W M, Vos P, Simons G, David S. Gene organization and expression in mesophyllic lactic acid bacteria. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:3398–3405. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Froseth B R, McKay L L. Development and application of pFM011 as a possible food-grade cloning vector. J Dairy Sci. 1991;75:914–923. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fürste J P, Pansegrau W, Frank R, Blöcker H, Scholz P, Bagdasarian M, Lanka E. Molecular cloning of the plasmid RP4 primase region in a multi-host-range tacP expression vector. Gene. 1986;48:119–131. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(86)90358-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holo H, Nes I F. High-frequency transformation by electroporation of Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris grown with glycine in osmotically stabilized media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:3119–3123. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.12.3119-3123.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes B F, McKay L L. Deriving phage-insensitive lactococci using a food-grade vector encoding phage and nisin resistance. J Dairy Sci. 1992;75:914–923. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishibashi N, Ono I, Kato K, Shigenaga T, Shinoda I, Okai H, Fukui S. Role of the hydrophobic amino acid residue in the bitterness of peptides. Agric Biol Chem. 1988;52:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kitazono A, Yoshimoto T, Tsuru D. Cloning, sequencing, and high expression of the proline iminopeptidase gene from Bacillus coagulans. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7919–7925. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.24.7919-7925.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kitazono A, Kitano A, Tsuru D, Yoshimoto T. Isolation and characterization of the propyl aminopeptidase gene (pap) from Aeromonas sobria: comparison with the Bacillus coagulans enzyme. J Biochem. 1994;116:818–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kok J. Genetics of the proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;87:15–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kok J, de Vos W M. The proteolytic system of lactic acid bacteria. In: Gasson M, de Vos W M, editors. Genetics and biotechnology of lactic acid bacteria. London, United Kingdom: Blackie Academic and Professional; 1994. pp. 169–210. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kunji E R S, Mireau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings W N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langsgrud T, Reinbold G W, Hammond E G. Proline production by Propionibacterium shermanii P59. J Dairy Sci. 1977;60:16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law J, Buist G, Haandrikman A, Kok J, Venema G, Leenhouts K. A system to generate chromosomal mutations in Lactococcus lactis which allows fast analysis of targeted genes. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:7011–7018. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.24.7011-7018.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leenhouts K J, Bolhuis A, Venema G, Kok J. Construction of a food-grade multiple copy integration system for Lactococcus lactis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1998;49:417–423. doi: 10.1007/s002530051192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leenhouts K J, Buist G, Bolhuis A, ten Berge A, Kiel J, Dabrowska M, Venema G, Kok J. A general system for generating unlabelled gene-replacements in the bacterial chromosome. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;253:217–224. doi: 10.1007/s004380050315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leenhouts K J, Gietema J, Kok J, Venema G. Chromosomal stabilization of the proteinase genes in Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991a;57:2568–2575. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.9.2568-2575.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leenhouts K J, Kok J, Venema G. Stability of integrated plasmids in the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2726–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2726-2735.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leenhouts K J, Kok J, Venema G. Replacement recombination in Lactococcus lactis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4794–4798. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4794-4798.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leenhouts K J, Venema G. Lactococcal plasmid vectors. In: Hardy K G, editor. Plasmids: a practical approach. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1993. pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayo B, Kok J, Venema K, Bockelmann W, Teuber M, Reinke H, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequence of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:38–44. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.38-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Panon G. Purification and characterization of a proline iminopeptidase from Propionibacterium shermanii 13673. Lait. 1990;70:439–452. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rauen H M. Biochemisches Taschenbuch. Vol. 2. Berlin, Germany: Springer Verlag; 1964. pp. 90–104. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ross P, O’Gara F, Condon S. Thymidilate synthetase gene from Lactococcus lactis as a gene marker: an alternative to antibiotic resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;52:2156–2163. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.7.2164-2169.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rottlander E, Trautner T A. Genetic and transfection studies with Bacillus subtilis phage SP50. Mol Gen Genet. 1970;108:47–60. doi: 10.1007/BF00343184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salström S, Espinosa C, Langsrud T, Sorhaug T. Cell wall, membrane and intracellular peptidase activities of Propionibacterium shermanii. J Dairy Sci. 1989;72:342–350. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith P K, Krohn R I, Hermanson G T, Mallia A K, Gartner F H, Provenzano M D, Fujimoto E K, Goeke N M, Olson B J, Klenk D C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terzaghi B E, Sandine W E. Improved medium for lactic streptococci and their bacteriophages. Appl Microbiol. 1975;29:807–813. doi: 10.1128/am.29.6.807-813.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Asseldonk M, de Vos W M, Simons G. Functional analysis of the Lactococcus lactis usp45 secretion signal in the secretion of a homologous proteinase and a heterologous α-amylase. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;240:428–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00280397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van de Guchte M, Kodde J, van der Vossen J M B M, Kok J, Venema G. Heterologous gene expression in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis: synthesis, secretion, and processing of the Bacillus subtilis neutral protease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2606–2611. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2606-2611.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Guchte M, van der Lende T, Kok J, Venema G. Distance-dependent translational coupling and interference in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;227:65–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00260708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van de Guchte M, van der Vossen J M B M, Kok J, Venema G. Construction of a lactococcal expression vector: expression of hen egg white lysozyme in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:224–228. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.1.224-228.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Vossen J M B M, van der Lelie D, Venema G. Isolation and characterization of Streptococcus cremoris Wg2-specific promoters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:2452–2457. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.10.2452-2457.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visser S. Proteolytic enzymes and their relation to cheese ripening. J Dairy Sci. 1993;76:329–350. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequence of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoshimoto T, Tsuru D. Proline iminopeptidase from Bacillus coagulans. J Biochem. 1985;97:1447–1485. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a135202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zabarovsky E R, Winberg G. High efficiency electroporation of ligated DNA into bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5912. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.19.5912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]