Abstract

Background

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) are frequent and associated with significant health care burden. National epidemiological data are limited. Our objective is to characterize the Portuguese population admitted with PHFs and analyze therapeutic management, the impact of associated lesions, and mortality rate.

Methods

This was a retrospective, observational study of admissions from mainland public hospitals (2000-2015), with primary or secondary diagnosis of PHFs. Incomplete records, pathologic lesions, malunion/nonunion, and hardware removal were excluded. Age, gender, admission date, hospitalization period, associated injuries, treatment, and mortality were recorded.

Results

A total of 19,290 patients were included. Through the analyzed period, an increase in the absolute number and incidence of PHFs was observed. The mean age at diagnosis was 62.6 ± 21.0 years old (57% elderly; 63.5% female). The mean length of stay was 10.0 ± 14.1 days, higher in patients submitted to arthroplasty (P < .001) and in those with associated fractures (25%; P < .001). A total of 14,482 patients were operated, most frequently with open reduction and internal fixation (28%). The inpatient mortality rate was 3.2%, significantly higher in patients with associated fractures (odds 2.77 for lower limb vs. upper limb).

Conclusion

There is a trend toward an increase in surgical management of PHFs. The relative proportion of open reduction and internal fixation and arthroplasty (particularly reverse arthroplasty) increased, probably reflecting biomechanical implant properties, fracture pattern, and demand for better functionality. Associated fractures are an important comorbidity, associated with increased mortality and length of stay.

Keywords: Shoulder, Humeral fractures, Epidemiology, Osteosynthesis, Hemiarthroplasty, Reverse arthroplasty

Proximal humerus fractures (PHFs) are among the most frequent bone fractures in adults, representing about 5.7% of all cases and being the third most common nonvertebral fracture in the elderly (>64 years old), after femoral neck and distal radius fractures.5 PHFs have a unimodal distribution, peaking in the aged, typical of osteoporotic injuries.5,21,30 As elderly population continues to rise, the number of PHFs is expected to increase.27 Owing to the high prevalence and expected increase in incidence, they are associated with significant health care burden.23,27

The acute treatment of these lesions is challenging, time-consuming, expensive, and frequently controversial. Nonoperative management is the first line of treatment in up to 85% of patients, with surgical alternatives ranging from fixation to arthroplasty.2,3,9,13,15,33

Precise knowledge on PHF epidemiology and treatment tendencies of these fractures is essential to develop prevention strategies and to project and plan for future management and health care resource allocation.3,15 Several studies suggest that there is marked regional variation in the incidence and treatment of PHFs.2,9,16,25,35 However, nationwide information on the epidemiology of this injury in southern European countries is very scarce, with one available study from Spain including only elderly subjects (above 65 years old).24 Our main objective is to characterize the Portuguese population admitted to national health care system hospitals from 2000 to 2015 with PHFs and analyze their therapeutic management, the impact of associated lesions, and mortality rate.

Materials and methods

A retrospective, observational big data study was conducted. Eligible patients were identified by a national database on admissions from mainland public health service hospitals, provided by the Portuguese Ministry of Health's Authority for Health Services. We included all patients admitted, from 2000 to 2015, with primary or secondary diagnosis of PHFs, as classified by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM)—“closed proximal humeral fractures” and “open proximal humeral fractures”, coded 812.0 and 812.1, respectively. Patients with incomplete records, pathologic lesions, and admission for hardware removal or management of malunion/nonunion and patients treated conservatively in outpatient care were excluded. In addition, patients treated in private facilities were not included in our database. Recorded data included age (subsequently categorized into 3 subgroups—young: <18 years old, adult: 18-64 years old, and elderly: >64 years old), gender, admission date, length of stay (from admission to discharge, including both preoperative and postoperative periods), associated injuries, treatment received, and mortality rate.

A retrospective chart review (as per diagnosis and procedure) was performed owing to very large size database and limited access to data from all the hospitals. For validation purposes, convenience sampling from a single hospital database (in this case, a Portuguese level III trauma hospital) was used, as described in previous studies.8,19,36 Medical records, including clinical reports, physician assessment information, and/or surgical reports, from 65% (n = 623) of all patients admitted in this hospital were analyzed and compared with database codification, to evaluate matching and error rates and to validate the study results.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics, version 25 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Data were summarized using descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, frequency, percentage). The odds ratio was used to evaluate the epidemiological trends, using a 95% confidence interval. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

A total of 19,290 patients with PHFs admitted to Portuguese public health service hospitals were included. From 2000 to 2015, there was a significant and consistent increase in the absolute number of patients admitted with PHFs (977 patients in 2000 vs. 1600 patients in 2015; P < .001; Fig. 1). Simultaneously, there was an increase in the incidence from 9.49/100.000 person-years in 2000 to 15.45/100.000 person-years in 2015. The average age at diagnosis was 62.6 ± 21.0 years old, with a predominance of elderly patients (57%; P < .001) and a gradual increase of the mean age at diagnosis over the period studied (Fig. 2). Women were more frequently affected (63.5%; P < .001; Fig. 1) and typically at older age (69.0 ± 17.3 years vs. 51.5 ± 22.2 years old; P < .001).

Figure 1.

Absolute number of patients hospitalized with proximal humerus fractures, between 2000 and 2015, by gender. PHF, proximal humerus fracture.

Figure 2.

Mean age of hospitalized patients, diagnosed with proximal humerus fracture, by year.

Most patients suffered closed fractures (97.4%). Open fractures tended to occur in younger patients, with odds for open fractures of 1.5 in young and 1.3 in adult patients, when compared with the elderly (P < .05). Associated fractures were diagnosed in about a quarter of patients, most frequently in lower limb (12.6%) and upper limb (8.2%), followed by spine injuries (2%).

The mean length of stay was 10.0 ± 14.1 days, significantly higher in patients submitted to shoulder arthroplasty (11.6 days; P < .001) and in those with associated fractures (16.9 days; P < .001). Each associated fracture led to an increase of 6.8 days and each added year of age to an increase of 0.8 days in hospital stay.

Overall, 75% (n = 14482) of inpatients with PHFs were surgically treated, with a lower rate of procedures in the elderly (71.6%) vs. adult and young patients (with 78.8% and 85.3%, respectively; P < .001). From 2000 to 2015, there was an increase in the absolute number of surgically treated patients (Fig. 3), with an increase in the relative percentage of interventions in the elderly after 2010.

Figure 3.

Absolute number of surgeries for proximal humerus fractures performed between 2000 and 2015.

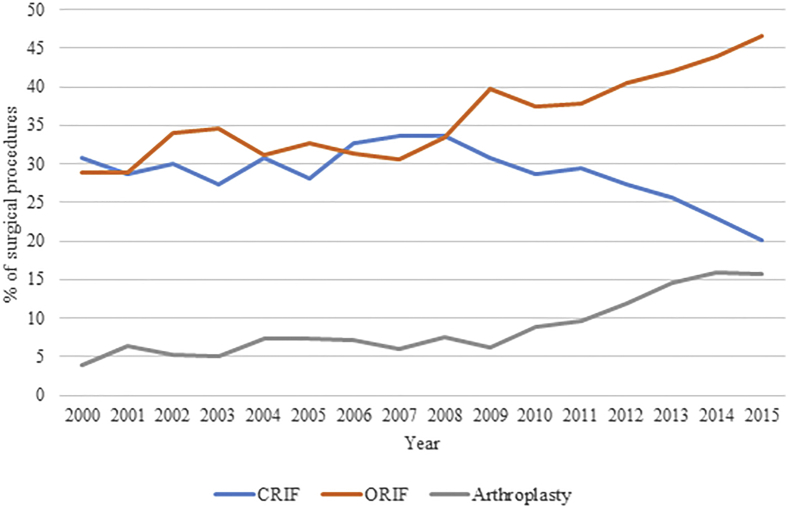

The surgical management of PHFs is depicted in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6. The most widely used surgical treatment was open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF; 28%), followed by closed reduction and internal fixation (CRIF; 21%). Although the relative percentage of ORIF performed during the study period increased, there was a declining use of CRIF (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Relative distribution of surgical treatment of PHF. PHF, proximal humerus fracture; CRIF, closed reduction and internal fixation; ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; CR no IF, closed reduction, no internal fixation.

Figure 5.

Relative distribution of surgical main procedures, by year. CRIF, closed reduction and internal fixation; ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation.

Figure 6.

Relative distribution of shoulder arthroplasty procedures, by year. Hemiarthro, hemiarthroplasty; TSA, total shoulder arthroplasty; RSA, reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Note that the ICD-9 coding for RSA was only introduced in 2021 (before this year, RSA might have been codified elsewhere).

Overall, only 7% of surgically treated patients were submitted to arthroplasty. However, its relative percentage rose steeply after 2010 (Fig. 5), similarly to ORIF. Hemiarthroplasty (HA) was the most widely used technique of replacement (70%), followed by total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA; 19.3%) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA; 10.7%—please note that RSA coding on ICD-9 is only available since 2011). Patients submitted to HA were significantly younger than those submitted to TSA or RSA (70.3 ± 11.0 vs. 74.4 ± 9.0 or 76.7 ± 6.5 years old, P < .001 in both). No significant differences were found between patients who underwent TSA and RSA (P = .093). In the study period, there was a declining use of HA, with a correspondent increase in RSA, the latter after 2011 (Fig. 6). Arthroplasty was mainly performed in the elderly (P < .001), with 95.6% of RSAs, 87.9% of TSAs, and 72.5% of HAs being performed in this group. Moreover, patients with associated fractures were less frequently submitted to shoulder replacement.

The inpatient mortality rate was 3.2%, with increased mortality in patients with associated lower limb injuries (odds = 2.77; 95% confidence interval = 2.3-3.2) when compared with upper limb fractures (P < .001).

Validation analysis revealed an overall sensitivity between codification and medical records of 86% (error rate of 14%). Among surgically treated patients, the sensitivity was 87% (13% error rate).

Discussion

With the global shift toward an aged population (even if age-adjusted incidence of fracture remains stable), the burden of osteoporotic fractures will be tremendous.12 Therefore, PHFs have gained importance, as this type of osteoporotic injury is associated with significant morbidity, functional disability, and socioeconomic impact. Consequently, national epidemiological studies may help health care providers to plan preventive and therapeutic interventions, directed to a particular injury.7

Between 2000 and 2015, the number of inpatients with PHFs increased in Portugal, predominantly in elderly women, what is consistent with current literature.2,5,15,18,25,35 Although there are no clear guidelines for decision on conservative or surgical treatment, in our study, there is a trend toward an increase in surgical management of PHFs. As suggested by Khatib et al,16 this may represent a more aggressive approach, supported by the continuous development of new techniques and implants associated with better outcomes.1,11,34 In the past, conventional plate fixation was associated with inadequate anchorage in osteoporotic bone. However, the current disseminated usage of locking plates has demonstrated better biomechanical characteristics and increased stability.22,34 Therefore, the relative proportion of ORIF has increased as opposed to CRIF. Besides, the role of shoulder replacement in the acute treatment of PHFs suffered substantial changes, as noted by the increase in the relative proportion of shoulder replacement (Fig. 5). These findings may represent a change in fracture pattern complexity, increased surgical differentiation, insights on the importance of accurate reduction of the greater tuberosity for shoulder function, and/or increased demand for better functionality among the elderly.2,37 In the elderly, poorer bone quality often precludes osteosynthesis, which may be associated with unsatisfying functional outcomes. This partly explains the increased use of arthroplasty, particularly RSA. As depicted in Fig. 6, since 2011, there was a noteworthy decline in HA as opposed to RSA, potentially associated with unpredictable motion and unsatisfactory outcomes of HA.9,11,13,16,18,28,37 Moreover, the ICD-9 code for RSA was only introduced in 2011. Before that time, RSAs were probably codified as TSA, as found in our validation sample. In addition, even afterward, some physicians probably did not updated their ICD-9 surgical coding, thereby justifying the constant percentage of TSA procedures in the study sample (with no significant differences found between patients who underwent TSA and RSA; P = .093).

However, the tendency for increased surgical management of PHFs in our population is conflicting with other studies, such as reported by McLean et al in a study on operative management of PHFs among hospitalized patients in Australia.25

Associated fractures are an important risk factor, as they are frequent (about 25%) and associated with increased mortality (especially lower limb lesions) and length of stay. These may represent a nondespicable proportion of polytraumatized patients and, as suggested in previous studies, illustrate that PHFs are an indirect sign of patients' frailty.4,26,29

The mean hospitalization period was surprisingly high. Whether conditioned by the type of injury, comorbidities, or complications, such long admission is associated with significant risk of nosocomial infections and increased health care costs.20 Although we have no data to justify this extended length of stay, it may be partially due to a preoperative delay (related with patient optimization, availability of operative rooms, surgical hardware, or specialized shoulder surgeons—which may also explain why patients who underwent arthroplasty stayed longer in the hospital) or increased pain.6,17,32 Therefore, future studies may address the reasons for high hospitalization periods, and strategies may be defined to optimize care and reduce length of stay.

The retrospective nature of the study is a limitation. We only considered patients admitted with PHFs, excluding those treated in outpatient care and those treated in private facilities, underestimating the total incidence of PHFs. In addition, because only a small percentage of patients with PHFs deemed for conservative treatment are admitted for hospital stay, we have a high percentage of surgical treatment, biased by the lack of those treated in outpatient basis.

The accuracy of our estimates is conditioned by proper coding. ICD-9 does not allow for fracture classification, and collected data do not indicate complications, revision surgery, patient-reported and functional outcomes, implant survival, or other factors that may affect treatment decision-making. Second, analysis of treatment options (Fig. 4) shows a surprisingly high rate of “other” procedures, other than ORIF, CRIF, and arthroplasty. We believe this is due to separate coding of surgical procedures for pediatric patients and those with fracture dislocations in ICD-9. Third, TSA coding was probably overused. As is defined in the article, during part of the study period, the RSA could not be coded as such and it was coded elsewhere, probably as another type of arthroplasty. Because there was no RSA code before 2011, data on its use can only be properly interpreted after this year. Future works may prospectively collect data and bring new insights on PHF management.

The limitations of big data analysis (such as missing or duplicate data, poor coding, among others) render large data sets inherently inaccurate.10,14,31 Although our study validation was restricted to a retrospective chart review, our overall sensitivity was estimated at 86%. This value is consistent with error rates reported in other studies with large databases, suggesting that these results may closely represent the Portuguese standard of care for PHFs.10,14,31

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the epidemiology of inpatients with PHFs and on their surgical management regarding the Portuguese population and in general southern European population. We believe the data depicted should be deeper studied in future longitudinal studies, with more information on the type of fracture and factors that might influence surgical decisions. Data on this topic are of upmost importance to the development of health care policies and of treatment algorithms for adequate management of PHFs.

Conclusion

This study found a temporal tendency toward an increase in the number of patients admitted with PHFs in Portuguese public health service hospitals. Alongside, there was an increase in the number of surgeries due to PHFs and in the relative proportion of patients who were submitted to ORIF and arthroplasty. An important mortality rate of about 3% was also found, mainly influenced by the presence of associated fractures.

Disclaimers:

Funding: No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Conflicts of interest: The authors, their immediate families, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated have not received any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

Footnotes

Miguel Relvas Silva and Daniela Linhares contributed equally to this work.

Nuno Neves and Manuel Ribeiro Silva contributed equally to this work.

The investigation has been submitted to the São João University Hospital Research Ethics Committee.

References

- 1.Austin D.C., Torchia M.T., Cozzolino N.H., Jacobowitz L.E., Bell J.E. Decreased reoperations and improved outcomes with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in comparison to hemiarthroplasty for geriatric proximal humerus fractures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33:49–57. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell J.E., Leung B.C., Spratt K.F., Koval K.J., Weinstein J.D., Goodman D.C., et al. Trends and variation in incidence, surgical treatment, and repeat surgery of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:121–131. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergdahl C., Ekholm C., Wennergren D., Nilsson F., Moller M. Epidemiology and patho-anatomical pattern of 2,011 humeral fractures: data from the Swedish Fracture Register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17:159. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement N.D., Duckworth A.D., McQueen M.M., Court-Brown C.M. The outcome of proximal humeral fractures in the elderly: predictors of mortality and function. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:970–977. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.96B7.32894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Court-Brown C.M., Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: a review. Injury. 2006;37:691–697. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo A.M., Luthringer T.A., Frost A., Khabie L., Roche C., Zuckerman J.D., et al. Does reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fracture portend poorer outcomes than for elective indications? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30:40–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2020.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epidemiology is a science of high importance. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1703. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04243-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fanuele J., Koval K.J., Lurie J., Zhou W., Tosteson A., Ring D. Distal radial fracture treatment: what you get may depend on your age and address. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1313–1319. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Floyd S.B., Campbell J., Chapman C.G., Thigpen C.A., Kissenberth M.J., Brooks J.M. Geographic variation in the treatment of proximal humerus fracture: an update on surgery rates and treatment consensus. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14:22. doi: 10.1186/s13018-018-1052-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg S.I., Niemierko A., Turchin A. Analysis of data errors in clinical research databases. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2008;2008:242–246. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hardeman F., Bollars P., Donnelly M., Bellemans J., Nijs S. Predictive factors for functional outcome and failure in angular stable osteosynthesis of the proximal humerus. Injury. 2012;43:153–158. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harvey N., Dennison E., Cooper C. Osteoporosis: impact on health and economics. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:99–105. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasty E.K., Jernigan E.W., 3rd, Soo A., Varkey D.T., Kamath G.V. Trends in surgical management and costs for operative treatment of proximal humerus fractures in the elderly. Orthopedics. 2017;40:e641–e647. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170411-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong M.K., Yao H.H., Pedersen J.S., Peters J.S., Costello A.J., Murphy D.G., et al. Error rates in a clinical data repository: lessons from the transition to electronic data transfer--a descriptive study. BMJ Open. 2013;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannus P., Palvanen M., Niemi S., Sievanen H., Parkkari J. Rate of proximal humeral fractures in older Finnish women between 1970 and 2007. Bone. 2009;44:656–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khatib O., Onyekwelu I., Zuckerman J.D. The incidence of proximal humeral fractures in New York State from 1990 through 2010 with an emphasis on operative management in patients aged 65 years or older. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1356–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King J.J., Patrick M.R., Struk A.M., Schnetzer R.E., Farmer K.W., Garvan C., et al. Perioperative factors affecting the length of hospitalization after shoulder arthroplasty. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2017;1:e026. doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-17-00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klug A., Gramlich Y., Wincheringer D., Schmidt-Horlohe K., Hoffmann R. Trends in surgical management of proximal humeral fractures in adults: a nationwide study of records in Germany from 2007 to 2016. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2019;139:1713–1721. doi: 10.1007/s00402-019-03252-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koval K.J., Lurie J., Zhou W., Sparks M.B., Cantu R.V., Sporer S.M., et al. Ankle fractures in the elderly: what you get depends on where you live and who you see. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19:635–639. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000177105.53708.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lagoe R.J., Johnson P.E., Murphy M.P. Inpatient hospital complications and lengths of stay: a short report. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:135. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Launonen A.P., Lepola V., Saranko A., Flinkkila T., Laitinen M., Mattila V.M. Epidemiology of proximal humerus fractures. Arch Osteoporos. 2015;10:209. doi: 10.1007/s11657-015-0209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laux C.J., Grubhofer F., Werner C.M.L., Simmen H.P., Osterhoff G. Current concepts in locking plate fixation of proximal humerus fractures. J Orthop Surg Res. 2017;12:137. doi: 10.1186/s13018-017-0639-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maravic M., Briot K., Roux C., College Francais des Medecins R. Burden of proximal humerus fractures in the French National Hospital Database. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100:931–934. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez-Huedo M.A., Jimenez-Garcia R., Mora-Zamorano E., Hernandez-Barrera V., Villanueva-Martinez M., Lopez-de-Andres A. Trends in incidence of proximal humerus fractures, surgical procedures and outcomes among elderly hospitalized patients with and without type 2 diabetes in Spain (2001-2013) BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18:522. doi: 10.1186/s12891-017-1892-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean A.S., Price N., Graves S., Hatton A., Taylor F.J. Nationwide trends in management of proximal humeral fractures: an analysis of 77,966 cases from 2008 to 2017. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2019;28:2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olsson C., Petersson C., Nordquist A. Increased mortality after fracture of the surgical neck of the humerus: a case-control study of 253 patients with a 12-year follow-up. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74:714–717. doi: 10.1080/00016470310018252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palvanen M., Kannus P., Niemi S., Parkkari J. Update in the epidemiology of proximal humeral fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;442:87–92. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000194672.79634.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosas S., Law T.Y., Kurowicki J., Formaini N., Kalandiak S.P., Levy J.C. Trends in surgical management of proximal humeral fractures in the medicare population: a nationwide study of records from 2009 to 2012. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:608–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rotman D., Giladi O., Senderey A.B., Dallich A., Dolkart O., Kadar A., et al. Mortality after complex displaced proximal humerus fractures in elderly patients: conservative versus operative treatment with reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 2018;9 doi: 10.1177/2151459318795241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roux A., Decroocq L., El Batti S., Bonnevialle N., Moineau G., Trojani C., et al. Epidemiology of proximal humerus fractures managed in a trauma center. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:715–719. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott I.A. Hope, hype and harms of big data. Intern Med J. 2019;49:126–129. doi: 10.1111/imj.14172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh A., Yian E.H., Dillon M.T., Takayanagi M., Burke M.F., Navarro R.A. The effect of surgeon and hospital volume on shoulder arthroplasty perioperative quality metrics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slobogean G.P., Johal H., Lefaivre K.A., MacIntyre N.J., Sprague S., Scott T., et al. A scoping review of the proximal humerus fracture literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:112. doi: 10.1186/s12891-015-0564-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sudkamp N., Bayer J., Hepp P., Voigt C., Oestern H., Kaab M., et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of proximal humeral fractures with use of the locking proximal humerus plate. Results of a prospective, multicenter, observational study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1320–1328. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sumrein B.O., Huttunen T.T., Launonen A.P., Berg H.E., Fellander-Tsai L., Mattila V.M. Proximal humeral fractures in Sweden-a registry-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2017;28:901–907. doi: 10.1007/s00198-016-3808-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassar M., Holzmann M. The retrospective chart review: important methodological considerations. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2013;10:12. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2013.10.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yahuaca B.I., Simon P., Christmas K.N., Patel S., Gorman R.A., 2nd, Mighell M.A., et al. Acute surgical management of proximal humerus fractures: ORIF vs. hemiarthroplasty vs. reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29:S32–S40. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]