Abstract

Introduction

Electrophysiology (EP) procedures are nowadays the gold-standard method for tachyarrhythmia treatment with impressive success rates, but also with a considerable risk of complications, mainly vascular. A systematic review and meta-analysis was performed to evaluate the safety of ultrasound (US)-guided femoral vein access in EP procedures compared to the traditional anatomic landmark-guided method.

Methods

We searched Pubmed (MEDLINE), Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane electronic databases for relevant entries, dated from January 1st, 2000 to June 30th, 2021. Only observational studies and randomized controlled trials were included in this analysis. Data extraction included study details, patient characteristics, procedure details, and all types of vascular complications. Complications were classified as major if any intervention, prolongation of hospitalization, or readmission was required.

Results

9 studies (1 randomized controlled trial and 8 observational), with 7858 participants (3743 in the US-guided group, 4115 in the control group), were included in the meta-analysis. Overall vascular complication rates were significantly decreased in the US-guided group compared to the control group (1.2 versus 3.2%, RR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.27–0.53), in all EP procedures. Sub-group analysis of AF ablation procedures yielded similar results (RR 0.41, 95% CI, 0.29–0.58, p < 0.00001). The event reduction effect was significant for both major and minor vascular complications.

Conclusion

US-guided vascular access in EP procedures is associated with significantly reduced vascular complications, compared to the standard anatomic landmark-guided approach, regardless of procedure complexity.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Vascular access, Catheter ablation, Electrophysiology, Complication

1. Introduction

Electrophysiology (EP) procedures are currently the cornerstone of tachyarrhythmia treatment, with remarkable success rates. It is estimated that almost 300,000 catheter ablations are performed in Europe annually [1]. However, despite the continuous implementation of cutting-edge technologies, these procedures still have a considerable risk of complications. Among them, vascular access-related complications, including hematomas, bleeding, pseudoaneurysms, arteriovenous fistulas, and retroperitoneal hematomas, are the most common and have been associated with increased risk of morbidity, mortality, and health-care costs.

Several studies have shown the feasibility, efficacy and safety of ultrasound (US) guidance for femoral vascular access, compared to the traditional anatomic landmark-guided (ie. symphysis pubis and anterior superior iliac spine, inguinal ligament and femoral artery impulse) approach, in various patient groups. The US-guided method improves first pass and overall success rates, shortens time to successful cannulation and minimizes the risk of vascular complications [[2], [3], [4]].

This technique has been adopted as standard practice by several medical specialties, such as anesthetists, emergency physicians, critical care professionals, nephrologists, and pediatricians [5]. However, the majority of electrophysiologists still seem to prefer the conventional method. Evidence on US-guided vascular access in EP procedures emerged during the last decade with encouraging results. Safe vascular access is particularly important during ablation procedures for atrial fibrillation where multiple sizeable introducers are often used, patients are in uninterrupted anticoagulation and same-day discharge is aimed. Furthermore, arterial access, for the ablation of ventricular arrhythmias and retrograde approach for accessory pathway ablation, is safer with the use of US, especially in obese patients with poorly palpable femoral arteries or in cases where the femoral vein lies below the femoral artery. However, it is not yet considered as a standard of care in such procedures and has not gained universal application, mainly due to cost and training issues.

The objective of this meta-analysis is to review the recently published data and assess whether femoral vein cannulation under US guidance decreases the risk of vascular complications in EP procedures.

2. Methods

The study was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive literature search of Pubmed (MEDLINE), Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane electronic databases was conducted for the identification of relevant entries. We used the keyword string ‘ultrasound’ and ‘femoral’ or ‘vascular’ and ‘electrophysiology’ or ‘electrophysiological’ or ‘catheter ablation’ (Supplementary Table S1). Date filter was applied to include publications from January 1st, 2000 to June 30th, 2021. No language restrictions were applied.

We included prospective and retrospective observational studies and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), which compared the vascular complication rates of the US-guided versus the conventional anatomic landmark-guided technique for percutaneous femoral vein access during any EP procedures. Conference abstracts were not eligible. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts of the identified reports. The full texts of all potentially relevant papers were then assessed for inclusion in the analysis. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Data extraction included publication details (publication year, authors, countries of origin), study design, enrollment period, inclusion/exclusion criteria, sample size, patient characteristics (age, gender, body weight index, use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant agents before the procedure) and procedure details (type of procedure, puncture needle size, periprocedural anticoagulant administration, vascular access time, first pass success rate, inadvertent arterial puncture, total procedure time, types and rates of vascular complications). The total number of vascular complications was the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes were: i. major vascular complications, ii. minor vascular complications, iii. inadvertent arterial punctures, iv. total vascular complications in atrial fibrillation (AF) ablation procedures. Vascular complications were classified as major in case of a clinically overt hematoma, bleeding, arteriovenous fistula, pseudoaneurysm, or retroperitoneal hematoma, and required intervention (percutaneous thrombin injection, surgical repair, blood transfusion), prolonged hospitalization, or readmission. All other complications were classified as minor.

We used Review Manager Version 5.4 and R Version 4.0.2 software for statistical analysis. A random-effects model (Mantel-Haenszel method) was selected for the calculation of pooled intervention effects on dichotomous outcomes. Risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were measured and a two-sided p-value <0.05 on the z-test was considered statistically significant. We also estimated the numbers needed to treat (NNT), deriving from total and major event rates. Forest plots for each intervention effect outline the statistical results. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by visual inspection of the forest plots and calculation of x2 heterogeneity statistic tests. Heterogeneity was also considered substantial if the p-value was <0.10 in the chi-square test and if the I2 statistic exceeded 50%. Sensitivity analysis was performed to assess the impact of anticoagulation strategy during catheter ablation procedures on the pooled estimate of the vascular complication rates and the heterogeneity across studies. Meta-regression analysis was conducted for the assessment of the impact of mean body mass index (BMI) in the studies on total complication rates. Data were also processed in a sub-group analysis, based on the study design. A funnel plot was created for publication bias assessment. Risk of bias was assessed using the Revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized trials (RoB 2) and the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions tool (ROBINS-I) [6,7].

3. Results

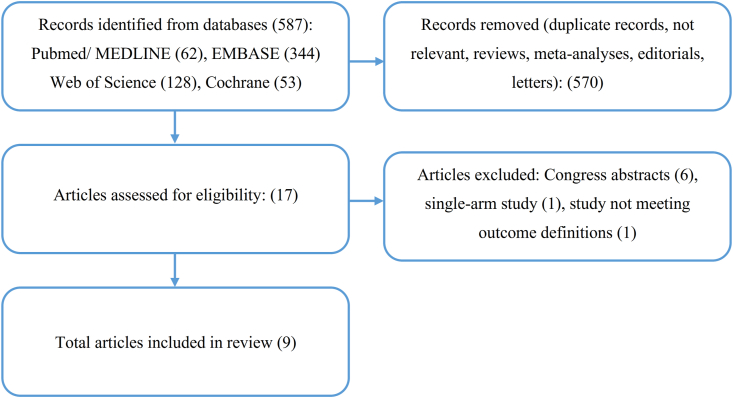

The outline of the study selection process is depicted in a PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). Initial electronic database screening identified 587 records. Of them, 570 articles were excluded, due to duplication, not relevance, or not meeting the inclusion criteria. We assessed 17 full-text studies for eligibility. Six congress abstracts, 1 single-arm study, and 1 study not meeting the outcome definitions were excluded. Finally, 9 studies were included in the meta-analysis: 1 RCT and 8 observational cohort studies (3 prospective, 3 retrospective, 2 not specified) [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]]. The basic study characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Five studies included only AF catheter ablation procedures while 4 studies included all EP procedures. The sample size for each study ranged from 36 to 3420 participants and the summed study population for the analysis was 7858 patients; 3743 in the US (intervention) group and 4115 in the non-US (control) group.

Fig. 1.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the studies included in the analysis.

| 1st author | Year | Country | Design | Enrollment period | EP Procedure | Redo (%) | Sample size (US/non-US) | Age (mean ± SD) | Male (%) | BMI (mean ± SD) | Periprocedural anticoagulation status | Protamine use (%) | Puncture time (sec) (mean ± SD or median [IQR]) |

Procedure time (min) (mean ± SD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | non-US | US | non-US | ||||||||||||||

| Tanaka-Esposito | 2013 | USA | Single-center, observational, retrospective cohort | January 2005–December 2006 (non-US) July 2008–May 2010 (US) |

AF ablation | NR | 3420 (1511/1909) | NR | 77.6 | NR | UI/I | 100 | NR | NR | |||

| Errahmouni | 2014 | Monaco | Single center, observational, retrospective cohort | April 2012–October 2012 (non-US) November 2012–June 2013 (US) | All EP procedures | NR | 300 (150/150) | 64.6 ± 17 | 65.3 | 28.2 ± 4.5 | UI | 100 | 280 ± 151 | NR | NR | ||

| Wynn | 2014 | UK | Single-center, observational, prospective cohort | May 2012–September 2012 (non-US) October 2012–February 2013 (US) |

AF ablation | 32 | 309 (163/146) | 58.9 ± 10.2 | 72.5 | 29.6 ± 4.6 | UI | 88.3 | NR | 167 ± 4 | 184 ± 53 | ||

| Rodriguez-Munoz | 2015 | Spain | Single center, observational, prospective cohort | NR | All EP procedures | NR | 36 (24/12) | 63.9 ± 19.4 | 69.4 | 26.0 ± 4.6 | NR | NR | 87.3 ± 94.3 60 [30.0–90.0] (per single puncture) |

238.1±294.7 120[46.0-422.0] (per single puncture) |

NR | ||

| Sharma | 2016 | USA | Single center, observational, prospective cohort | October 2014–May 2015 (non-US) June 2015–January 2016 (US) |

All EP procedures | NR | 720 (360/360) | 57.9 ± 16 | 53.0 | 30.0 ± 7.0 | UI | NR | NR | NR | |||

| Yamagata | 2017 | Czech Republic Japan |

Multicenter (4 centers), randomized controlled trial | March 2016–November 2016 | AF ablation | 37 | 319 (159/160) | 63.0 ± 8 | 61.4 | 29.6 ± 5.2 | UI | 63.6 | 288 [191–370] | 369 [257-584] | NR | ||

| Ströker | 2018 | Belgium | Multicenter (2 centers), observational cohort | June 2012–August 2016 (non-US) August 2016–June 2017 (US) |

AF ablation | 0 | 1435 (300/1135) | 60.0 ± 12.0 | 65.1 | 27.0 ± 4.0 | UI | NR | NR | 60 ± 18 | 79 ± 27 | ||

| Futyma | 2020 | Poland | Single center, observational cohort | November 2016–April 2019 (US) November 2016–September 2018 (non-US) | All EP procedures | NR | 981 (876/105) | 55.5 ± 16.5 | 45.2 | 28 ± 5.5 | NR | NR | NR | NR | |||

| La Greca | 2020 | Italy | Single-center, observational, retrospective cohort | January 2010–March 2016 (non-US) March 2016–January 2020 (US) | AF ablation (±CTI ablation) | 20 | 374 (224/150) | 60 ± 6 | 74 | 27 ± 3 | UI | 0 | NR | 180 ± 30 | 180 ± 30 | ||

AF: atrial fibrillation, BMI: body mass index, CTI: cavotricuspid isthmus, EP: electrophysiology, I: interrupted, non-US: non-ultrasound group, NR: not reported, UI: uninterrupted, US: ultrasound group.

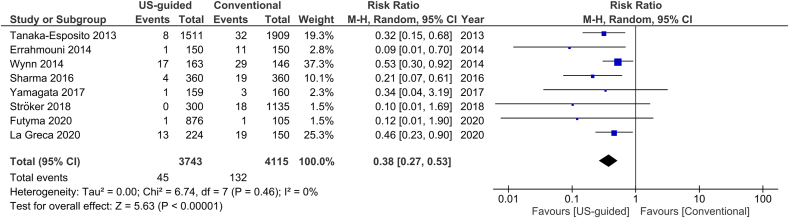

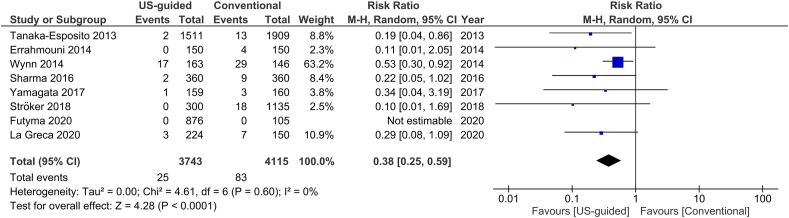

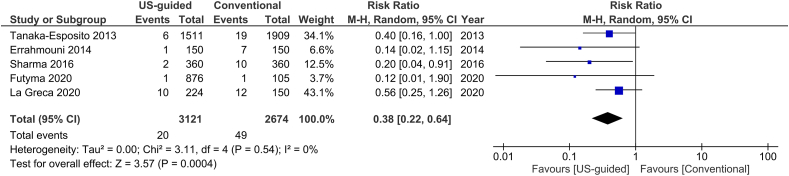

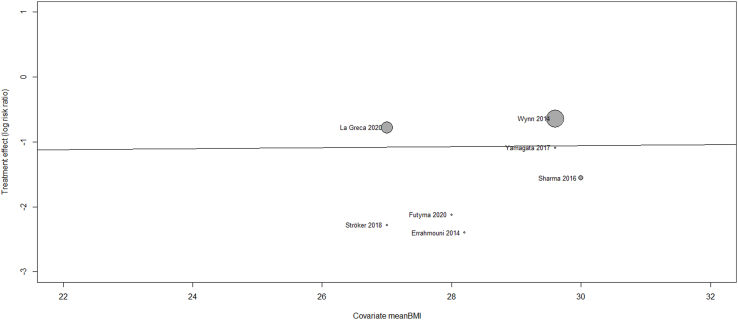

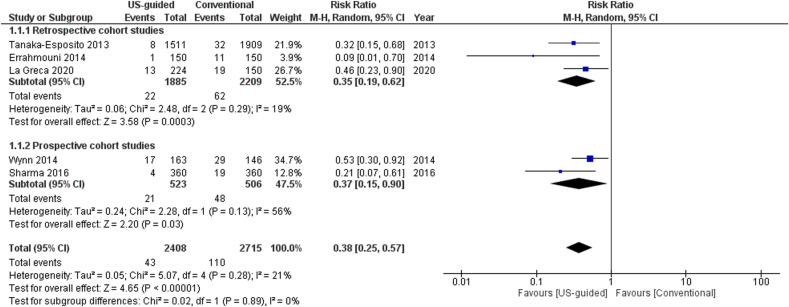

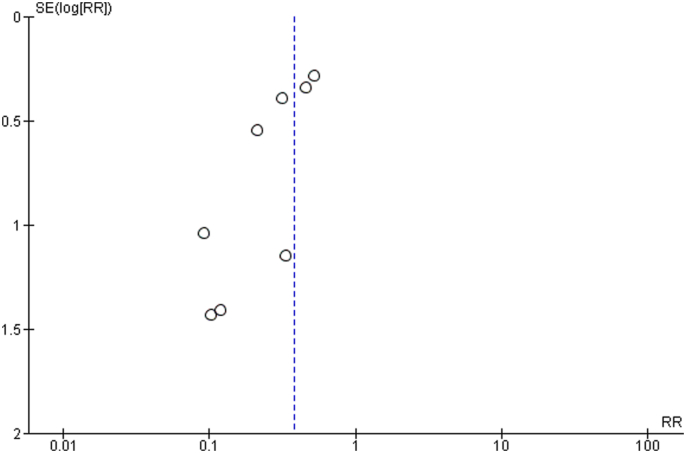

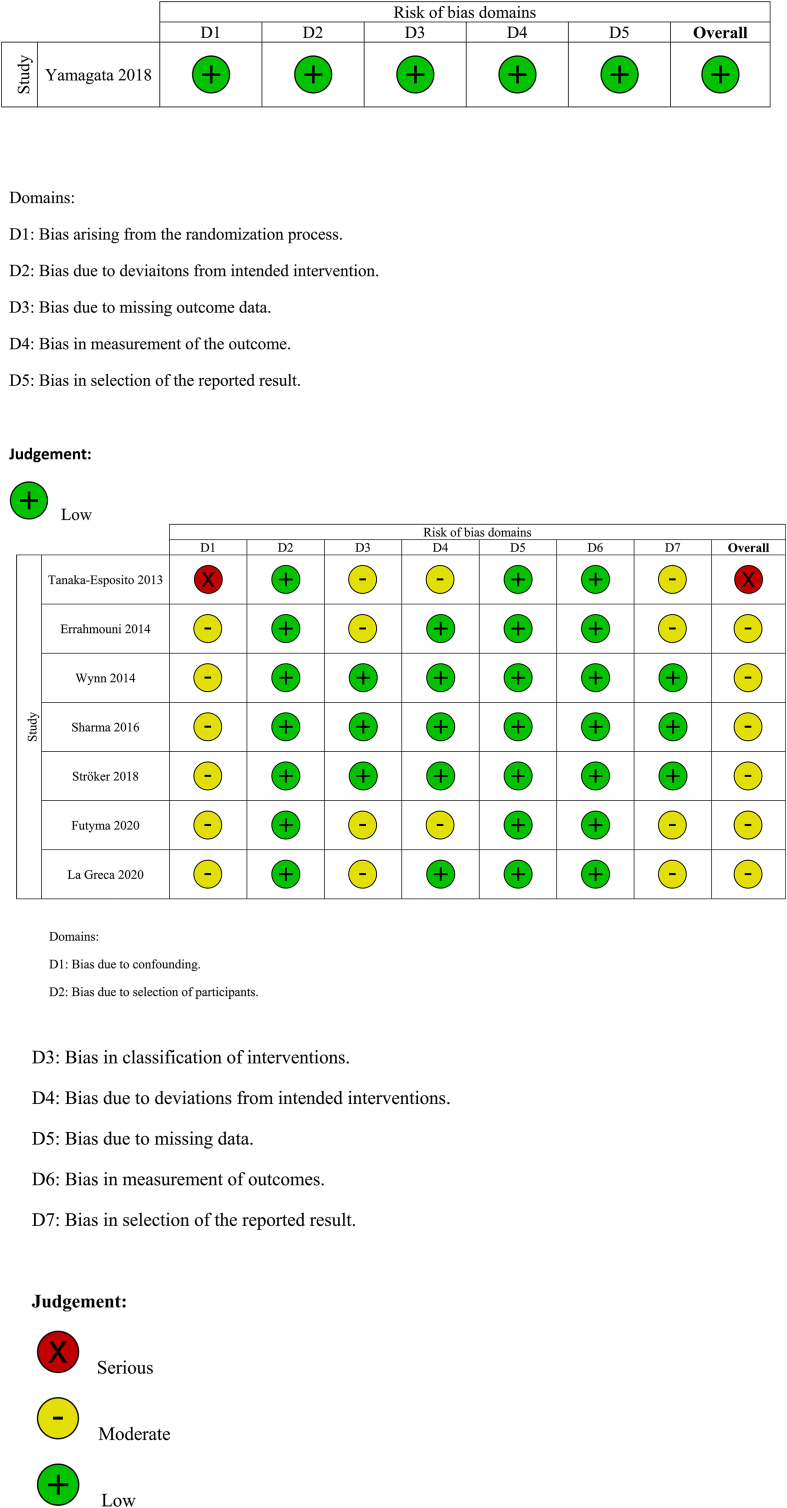

The total number of vascular complications in both groups was reported in 8 studies. US-guided group had a significantly decreased incidence of total vascular complications compared to non US-guided group (1.2 versus 3.2%, RR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.27–0.53, p < 0.00001, Fig. 2). The rate of major vascular complications (Table 2) was also reduced in the US group (0.7% versus 2%, RR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.25–0.59, p < 0.0001, Fig. 3). NNT were estimated to be 50 and 80 for all and major vascular events respectively. Similar findings resulted from the analysis for minor vascular complications (Table 3) (RR = 0.38, 95% CI, 0.22–0.59, p < 0.0004, Fig. 4). All tests for heterogeneity were not significant and the studies were homogenous for overall, major and minor vascular complication outcomes. Meta-regression analysis showed mean BMI did not significantly affect total vascular complications in the studies included (p-value 0.97) (Fig. 5). In the sub-group analysis based on the study design, the results for total vascular complications were similar for both prospective and retrospective observational cohort studies (Fig. 6). In the funnel plot, including 8 studies for the outcome of total vascular complications, an asymmetry in the scatter of small studies can be observed (Fig. 7). The risk of bias for each study in individual domains as well as the overall estimates are reported in Table 4. Low risk of bias was estimated for the RCT, whereas 7 observational cohort studies were at moderate and one at serious risk of bias, reflecting the inherent weaknesses of this study category.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of comparison: US-guided vs. Conventional, outcome: Total vascular complications.

Table 2.

Major vascular complications in the studies included in the analysis.

| Study | Total |

Hematoma or bleeding |

Pseudoaneurysm |

AV fistula |

Retroperitoneal bleed |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | nonUS | US | nonUS | US | nonUS | US | nonUS | US | nonUS | |

| Tanaka-Esposito | 2 | 13 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Errahmouni | 0 | 4 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Wynn | 17 | 29 | 17 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sharma | 2 | 9 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Yamagata | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ströker | 0 | 18 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Futyma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| La Greca | 3 | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

US: ultrasound group, nonUS: conventional group.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of comparison: US-guided vs. Conventional, outcome: Major vascular complications.

Table 3.

Minor vascular complications in the studies included in the analysis.

| Study | Total |

Hematoma or bleeding |

Pseudoaneurysm |

AV fistula |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | nonUS | US | nonUS | US | nonUS | US | nonUS | |

| Tanaka-Esposito | 6 | 19 | 3 | 17 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Errahmouni | 1 | 7 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sharma | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Futyma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| La Greca | 10 | 12 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

US: ultrasound group, nonUS: conventional group.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of comparison: US-guided vs. Conventional, outcome: Minor vascular complications.

Fig. 5.

Meta-regression analysis for the assessment of the effect of mean body mass index (BMI) on total vascular complication rates.

Fig. 6.

Sub-group analysis based on the study design of the observational cohort studies for the outcome of total vascular complications.

Fig. 7.

Funnel plot for the outcome of total vascular complications.

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment.

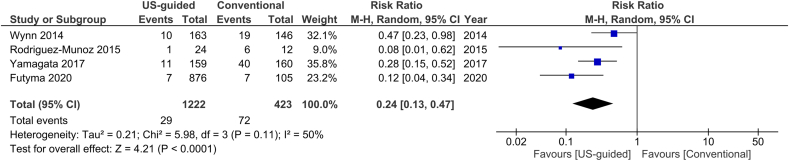

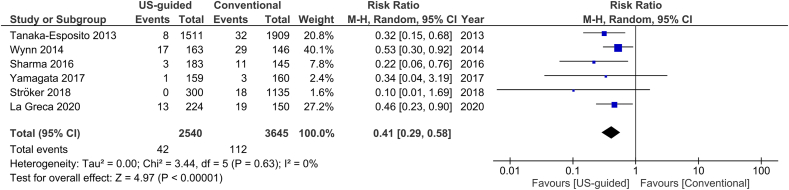

For the outcome of inadvertent arterial puncture, there was a relative risk reduction by 76% in the US group compared to the non-US group (2.4% versus 17%, Fig. 8). I2 was measured 50% for this outcome, rendering a moderate heterogeneity of the studies. Five studies included only AF ablation procedures, whereas another one provided data for this patient subgroup. When the analysis was restricted to these studies, we estimated a similar RR reduction, again in favor of the US group (0.41, 95% CI, 0.29–0.58, p < 0.00001, Fig. 9).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of comparison: US-guided vs. Conventional, outcome: Inadvertent arterial puncture.

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of comparison: US-guided vs. Conventional, outcome: Total vascular complications in AF studies.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest meta-analysis published for this subject, including only RCTs and observational studies. We found a significant risk reduction by 62% for vascular complications for the US-guided femoral venipuncture, compared to the conventional, anatomic landmark-guided technique. The estimated NNT indicate that the adoption of routine use of US for venous access in EP procedures could prevent a considerable number of vascular complications with a potential beneficial impact on morbidity, hospital stay length, and total costs, especially in high volume EP centers.

Our findings keep in line with the results of a previous meta-analysis, which included 4 observational only trials with 4605 patients and showed 60% and 66% relative risk reduction in major and minor vascular complications respectively [17]. Only one RCT has been conducted in this specific field till date [13]. It enrolled 320 patients who underwent catheter ablation for AF, randomized in a 1:1 fashion. The study failed to demonstrate a difference in major vascular complication rates between the two arms and was prematurely terminated due to lower-than-expected events. An additional contributing factor to the neutral study result was the considerable cross-over rate (9%) from the conventional to the US group. However, several secondary intra-procedural parameters were in favor of US guidance, irrespective of operator experience.

The rate of vascular complications during catheter ablation procedures in our study population remains within the ranges of previously published reports [18]. Of note, Wynn et al. found a remarkably high number of major complications, while Yamagata et al. reported a quite frequent rate of inadvertent arterial punctures. The origins of these discrepancies are uncertain, but they likely did not impact the outcomes of the meta-analysis as random effects models were employed. Among EP procedures, AF and ventricular tachycardia ablations have a higher incidence of femoral access complications [12]. This occurs mainly due to multiple and large sheath insertions as well as uninterrupted periprocedural anticoagulation, which is currently the routine practice for AF ablation [19]. Our analysis for only AF ablation studies confirms the previous results. The protective role of US guidance remains at the same level for these high-risk patients, showing 59% relative risk reduction for vascular complications. Interestingly, pre-procedural antiplatelet and anticoagulant treatment does not affect the event rates [8,9,12,14,20]. Moreover, in our study, the sensitivity analysis for the assessment of the effect of periprocedural anticoagulation protocol did not show any difference on the pooled estimate of the total, major and minor vascular complication rates. US-guidance for venipuncture improves first pass success rates and decreases the total number of attempts as well as inadvertent arterial puncture rates. Thus, it can be helpful for populations with increased risk for vascular complications, such as females, obese, elderly patients, and patients with severe atherosclerosis [21].

Use of US is important not only for venous, but also arterial access especially when the retrograde approach for the ablation of ventricular arrhythmias or accessory pathways is selected. However, the studies included in our analysis do not provide enough data for the evaluation of the role of US guidance for arterial punctures. Sharma et al. found that arterial access was not a predictor for vascular complications in patients undergoing EP procedures, due to low event rates [12].

Several methods are used at the end of EP procedures in order to minimize the risk of vascular complications. The rate of intravenous protamine administration for heparin reversal is shown in Table 1. Manual compression after sheath removal was applied in all studies included in our analysis, whereas the use of closure devices was not reported. La Greca et al. found that figure-of-eight suture at the puncture site was associated with fewer complications. However, this correlation was not significant in the multivariate analysis [16].

Puncture time is significantly decreased when operators use US for vascular access [11]. In the ULTRA-FAST trial, total puncture time was 369 s (median, IQR 257–584) in the control group compared to 288 s (mean, IQR 191–370) in the US group (p < 0.001) [13]. Two other studies also reported a significant reduction in total procedure time [10,14]. Nevertheless, the reduction in total procedure time could be due to diverse catheter ablation strategies and increased center experience, since all procedures in the US groups were performed later compared to historical non-US groups.

Another favorable outcome of US-guided vein cannulation is the significantly reduced fluoroscopy time during the procedure, which can be explained by less use of X-ray to advance the guidewire into the inferior vena cava [13,16].

The anatomic relationship of the femoral vessels varies significantly among patients [22]. Imaging of the inguinal region with computed tomography revealed that, in the anteroposterior plane, femoral artery overlaps the femoral vein in two-thirds of the patients [23]. Real-time 2-dimensional US allows direct visualization of the vessels and contributes to the diagnosis of anatomic variations, which cannot be predicted if no imaging method is used. Inadvertent arterial puncture, even not considered as a vascular complication itself, may potentially predispose to severe clinical adverse events, especially in cases of uninterrupted anticoagulation.

Various US devices are currently widely available and have been used in the studies (Table 5). Rodriguez Munoz et al. used a wireless linear array US probe, which is probably more convenient for the operator and facilitates the preservation of sterile conditions during the procedure [11].

Table 5.

Ultrasound devices used in the studies.

| Study | Ultrasound device |

|---|---|

| Tanaka-Esposito | NR |

| Errahmouni | NR |

| Wynn | SonoSite S-ICU, Fujifilm SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA, USA |

| Rodriguez-Munoz | Accuson Freestyle, Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA |

| Sharma | SonoSite S-ICU, Fujifilm SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA, USA |

| Yamagata | Vivid I, GE Health Medical, Horten, Norway |

| Ströker | NR |

| Futyma | Esaote Biomedica 7050 AU3, Genoa, Italy |

| La Greca | NR |

NR: not reported.

Valsalva maneuver (VM) increases peripheral venous pressure and the diameter of the femoral vein [24]. Futyma et al. assessed the effectiveness of this technique during US-guided femoral venipunctures in EP procedures [15]. No significant differences in the rates of minor or major adverse events between the VM-supported and standard methods were observed, probably due to the low number of events. However, VM seemed to facilitate venous access and a trend towards a lower incidence of vascular complications was noted. It was suggested that VM can be also performed with the traditional anatomic landmark-guided technique. Moreover, it could be beneficial especially in patients who have anatomical abnormalities or small femoral vein diameters, such as women and underweight individuals.

Puncture needle size was reported in only 3 of the studies included, in which a 18-G (gauge) needle was used. However, there is evidence to support that introduction of a micropuncture needle (21-G) in combination with US guidance could potentially further reduce vascular access complications, especially in the high-risk anticoagulated patients [[25], [26], [27]].

Generally, physicians do not perform venipuncture under US guidance. Lack of equipment, time consumption, and insufficient training are the most frequently reported limiting factors [28]. However, US-guided femoral puncture in EP procedures has a rather easy learning curve and does not interfere with the normal workflow [29]. It is estimated that only six to seven cases are needed for operators to reach the beginning of puncture time plateau. Moreover, no difference in puncture times was found between senior operators and fellows [9]. No study about the financial evaluation of the technique has ever been performed. However, an economic analysis estimated an additional cost of less than £10 per procedure. It was also concluded that the implementation of US devices is in the long term cost-effective due to reduced complications [30].

Real-time US-guided venipuncture is currently recommended for patients undergoing AF ablation and/or electrophysiological procedures by international EP societies as a safer, faster, and more effective technique [19]. However, this method has not yet been widely adopted by electrophysiologists and only a minority uses vascular US devices in the EP lab routinely. We believe that this meta-analysis offers robust data which can influence the current clinical practice.

4.1. Limitations

Firstly, only one randomized study was included in the analysis. The majority of data was extracted from observational studies, which forms a potential source of bias. These studies have been conducted in large volume centers with high level of operator expertise, which led to limited number of complications. However, the lack of heterogeneity between studies and the high level of significance indicate unbiased results. Nevertheless, a large randomized prospective study would probably be needed to provide adequate number of data points and show a robust difference between the two techniques. Secondly, the definitions used for the classification and severity of vascular complications were not universal and minor discrepancies between studies may exist. Thirdly, subgroup analyses based on patient and procedure characteristics were not performed, since patient-level data were not available. Fourthly, publication bias cannot be adequately estimated, since only 8 studies were used for the analysis.

5. Conclusions

US-guided vascular access in EP procedures is associated with significantly reduced vascular complications, compared to the standard anatomic landmark-guided approach. Based on these findings, routine use of US-guidance for femoral vein cannulation should be considered and US devices may become part of the standard EP lab equipment.

Funding

None.

CRediT author statement

Konstantinos Triantafyllou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. Christos D Karkos: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft. Nikolaos Fragakis: Methodology, Writing - Original Draft, Supervision. Antonios P Antoniadis: Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Meletidou Magdalini: Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Vassilios Vassilikos: Conceptualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Indian Heart Rhythm Society.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipej.2022.01.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Raatikainen M.J.P., Arnar D.O., Merkely B., Nielsen J.C., Hindricks G., Heidbuchel H., et al. A decade of information on the use of cardiac implantable electronic devices and interventional electrophysiological procedures in the European society of cardiology countries: 2017 report from the European heart rhythm association. Europace. 2017;19:ii1–ii90. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prabhu M.V., Juneja D., Gopal P.B., Sathyanarayanan M., Subhramanyam S., Gandhe S., et al. Ultrasound-guided femoral dialysis access placement: a single-center randomized trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:235–239. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04920709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brass P., Hellmich M., Kolodziej L., Schick G., Smith A.F. Ultrasound guidance versus anatomical landmarks for subclavian or femoral vein catheterization. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD011447. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reusz G., Csomos A. The role of ultrasound guidance for vascular access. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:710–716. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lamperti M., Bodenham A.R., Pittiruti M., Blaivas M., Augoustides J.G., Elbarbary M., et al. International evidence-based recommendations on ultrasound-guided vascular access. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:1105–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2597-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterne J.A.C., Savović J., Page M.J., Elbers R.G., Blencowe N.S., Boutron I., et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterne J.A.C., Hernán M.A., Reeves B.C., Savović J., Berkman N.D., Viswanathan M., et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka-Esposito C.C., Chung M.K., Abraham J.M., Cantillon D.J., Abi-Saleh B., Tchou P.J. Real-time ultrasound guidance reduces total and major vascular complications in patients undergoing pulmonary vein antral isolation on therapeutic warfarin. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol. 2013;37:163–168. doi: 10.1007/s10840-013-9796-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Errahmouni A., Bun S.S., Latcu D.G., Saoudi N. Ultrasound-guided venous puncture in electrophysiological procedures: a safe method, rapidly learned. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1023–1028. doi: 10.1111/pace.12386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynn G.J., Haq I., Hung J., Bonnett L.J., Lewis G., Webber M., et al. Improving safety in catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: a prospective study of the use of ultrasound to guide vascular access. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:680–685. doi: 10.1111/jce.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez Muñoz D., Franco Díez E., Moreno J., Lumia G., Carbonell San Román A., Segura De La Cal T., et al. Wireless ultrasound guidance for femoral venous cannulation in electrophysiology: impact on safety, efficacy, and procedural delay. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:1058–1065. doi: 10.1111/pace.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma P.S., Padala S.K., Gunda S., Koneru J.N., Ellenbogen K.A. Vascular complications during catheter ablation of cardiac arrhythmias: a comparison between vascular ultrasound guided access and conventional vascular access. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:1160–1166. doi: 10.1111/jce.13042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamagata K., Wichterle D., Roubícek T., Jarkovský P., Sato Y., Kogure T., et al. Ultrasound-guided versus conventional femoral venipuncture for catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a multicentre randomized efficacy and safety trial (ULTRA-FAST trial) Europace. 2018;20:1107–1114. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ströker E., de Asmundis C., Kupics K., Takarada K., Mugnai G., De Cocker J., et al. Value of ultrasound for access guidance and detection of subclinical vascular complications in the setting of atrial fibrillation cryoballoon ablation. Europace. 2019;21:434–439. doi: 10.1093/europace/euy154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Futyma P., Ciąpała K., Sander J., Głuszczyk R., Futyma M., Kułakowski P. Ultrasound-guided venous access facilitated by the Valsalva maneuver during invasive electrophysiological procedures. Kardiol Pol. 2020;78:235–239. doi: 10.33963/KP.15188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.La Greca C., Cirasa A., Di Modica D., Sorgato A., Simoncelli U., Pecora D. Advantages of the integration of ICE and 3D electroanatomical mapping and ultrasound-guided femoral venipuncture in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol. 2021;61:559–566. doi: 10.1007/s10840-020-00835-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobolev M., Shiloh A.L., Di Biase L., Slovut D.P. Ultrasound-guided cannulation of the femoral vein in electrophysiological procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2017;19:850–855. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hindricks G., Potpara T., Dagres N., Arbelo E., Bax J.J., Blomström-Lundqvist C., et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2020;42:373. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehab648. 2021. 498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Calkins H., Hindricks G., Cappato R., Kim Y.H., Saad E.B., Aguinaga L., et al. HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2017;20:e1–e160. doi: 10.1093/europace/eux274. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu-Ray I., Khanra D., Kupó P., Bunch J., Theus S.A., Mukherjee A., et al. Outcomes of uninterrupted vs interrupted Periprocedural direct oral Anticoagulants in atrial Fibrillation ablation: a meta-analysis. J Arrhythm. 2021;37(2):384–393. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12507. Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherev D.A., Shaw R.E., Brent B.N. Angiographic predictors of femoral access site complications: implication for planned percutaneous coronary intervention. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;65:196–202. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes P., Scott C., Bodenham A. Ultrasonography of the femoral vessels in the groin: implications for vascular access. Anaesthesia. 2000;55:1198–1202. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2000.01615-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baum P.A., Matsumoto A.H., Teitelbaum G.P., Zuurbier R.A., Barth K.H. Anatomic relationship between the common femoral artery and vein: CT evaluation and clinical significance. Radiology. 1989;173:775–777. doi: 10.1148/radiology.173.3.2813785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Porth C.J., Bamrah V.S., Tristani F.E., Smith J.J. The Valsalva maneuver: mechanisms and clinical implications. Heart Lung. 1984;13:507–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng C., Rozen G., Biton Y., Leyton-Mange J., Barrett C. Direct ultrasound visualization in combination with micropuncture needle reduces vascular access complications in cardiac electrophysiological procedures. Europace. 2017;19:iii77. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dussault C., Baldinger S., Tedrow U.B., Michaud G., Koplan B., Stevenson W. Preventing vascular access complications for ablation on uninterrupted anticoagulation: impact of ultrasound guidance and micropuncture needle. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:S427–S514. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abhishek F., Heist E.K., Barrett C., Danik S., Blendea D., Correnti C., et al. Effectiveness of a strategy to reduce major vascular complications from catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol. 2011;30:211–215. doi: 10.1007/s10840-010-9539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchanan M.S., Backlund B., Liao M.M., Sun J., Cydulka R.K., Smith-Coggins R., et al. Use of ultrasound guidance for central venous catheter placement: survey from the American board of emergency medicine longitudinal study of emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med. 2014;21:416–421. doi: 10.1111/acem.12350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiles B.M., Child N., Roberts P.R. How to achieve ultrasound-guided femoral venous access: the new standard of care in the electrophysiology laboratory. J Intervent Card Electrophysiol. 2017;49:3–9. doi: 10.1007/s10840-017-0227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . NICE Technology appraisal guidance [TA49]; 2002. Guidance on the use of ultrasound locating devices for placing central venous catheters.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta49 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.