Abstract

Brochocin-C, produced by Brochothrix campestris ATCC 43754, is active against many strains of the closely related meat spoilage organism Brochothrix thermosphacta and a wide range of other gram-positive bacteria, including spores of Clostridium botulinum. Purification of the active compound and genetic characterization of brochocin-C revealed that it is a chromosomally encoded, two-peptide nonlantibiotic bacteriocin. Both peptides of brochocin-C are ribosomally synthesized as prepeptides that are typical of class II bacteriocins. They are cleaved following Gly-Gly cleavage sites to yield the mature peptides, BrcA and BrcB, containing 59 and 43 amino acids, respectively. Fusion of the nucleotides encoding the signal peptide of the bacteriocin divergicin A in front of the structural genes for either BrcA or BrcB allowed independent expression of each component by the general protein secretion pathway. This revealed the two-component nature of brochocin-C and the necessity for both peptides for activity. A 53-amino-acid peptide encoded downstream of brcB functions as the immunity protein (BrcI) for brochocin-C. In addition, the cloned chromosomal fragment revealed open reading frames downstream of brcI, designated brcT and brcD, that encode proteins with homology to ATP-binding cassette translocator and accessory proteins, respectively, involved in the secretion of Gly-Gly-type bacteriocins.

Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides or proteins, produced by bacteria, that generally have a narrow spectrum of antibacterial activity against closely related species. In recent years, bacteriocins of lactic acid bacteria have been studied as possible biological preservatives in foods. Bacteriocins were classified by Klaenhammer (18) into four groups. Class I bacteriocins, known as lantibiotics, are ribosomally produced, but they undergo extensive posttranslational modification to produce the active peptide. Nisin is a well-characterized lantibiotic produced by Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. This class I bacteriocin has a broad spectrum of activity that includes activity against many gram-positive bacteria and also inhibits the outgrowth of bacterial spores. It has been widely applied as a food preservative, but it has limited potential for biopreservation of meat because it is poorly soluble above pH 5.0 and it interacts with phospholipids (8, 17). Most of the well-characterized bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria are nonlantibiotic, heat-stable, low-molecular-weight class II bacteriocins (18). They are produced as prepeptides, and posttranslational modification is generally limited to cleavage of the N-terminal leader peptide following a Gly-Gly site. Class II bacteriocins can be subdivided into (i) peptides that contain a Tyr-Gly-Asn-Gly-Val-Xaa-Cys motif near their N termini and (ii) two-peptide bacteriocins. Most class II bacteriocins have a limited spectrum of antibacterial activity that restricts their usefulness for control of bacterial spoilage of meat and pathogenic microorganisms in meat.

Our laboratory has targeted the development of gene cassettes capable of producing multiple bacteriocins which, in combination, could have an antibacterial spectrum equivalent to or better than that of nisin and which are also suitable in preservation of fresh meat. As part of this strategy, we screened for bacteriocins from Brochothrix spp. that are active against Brochothrix thermosphacta (unpublished data). This gram-positive, facultative anaerobe is an important spoilage organism of meats stored at chill temperatures, because it can impart an off odor in vacuum- or modified-atmosphere-packaged meats (10). Problems arise when conditions of meat storage allow growth of B. thermosphacta, for example, with high pH (6.0 to 6.5) meat and/or at low concentrations of oxygen (5, 11, 12). B. thermosphacta was the only species in the genus Brochothrix, but through taxonomic and DNA hybridization studies of a number of strains isolated from a variety of sources, Talon et al. (34) in 1988 described a second species, Brochothrix campestris. Apart from its initial discovery and characterization, limited information on this organism is available. To date it has been isolated only from soil and grass; however, it is possible that in the past it was misidentified as B. thermosphacta.

Brochocin-C, a bacteriocin produced by B. campestris ATCC 43754, was originally discovered and classified as a bacteriocin by Siragusa and Nettles Cutter (30). It was reported to be active against 35 strains of B. thermosphacta, 10 strains of Listeria monocytogenes, and several strains of Carnobacterium, Enterococcus, Kurthia, Lactobacillus, and Pediococcus but not against gram-negative bacteria. Hence, brochocin-C is a good candidate for inclusion in an arsenal of bacteriocins that might be suitable for biopreservation of meats. In this study, we determined the biochemical and genetic characteristics of brochocin-C. Purification of the antimicrobial compound and determination of its amino acid sequence was used as the basis for cloning and DNA sequencing of the chromosomal bacteriocin genes. Heterologous expression of the structural and immunity genes of brochocin-C confirmed the role of these genes in the production of this potent bacteriocin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1, except for the target bacteria used to determine the antibacterial spectrum of brochocin-C. All strains were stored at −70°C in APT broth (All Purpose Tween; Difco Laboratories Inc., Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, except strains of Escherichia coli, which were stored under the same conditions in Luria-Bertani broth (LB) (29). Bacteriocin production by B. campestris was studied in APT broth and semidefined Casamino Acids medium (CAA) (14). E. coli strains inoculated into LB containing the appropriate antibiotic were grown with shaking at 37°C. Transformants of E. coli were selected on either LB or yeast extract-tryptone agar (Difco) with selective concentrations of ampicillin or erythromycin (200 μg ml−1). For growth of Carnobacterium transformants, a selective concentration of 5 μg of erythromycin per ml was used.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study (excluding strains used for determination of the antimicrobial activity spectrum)

| Bacterial strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristicsa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E. coli DH5α | F−endA1 hsdR17 (rK− mK+) supE44 λ− thi-1 recA1 gyrA96 relA1 Δ(argF-lacZYA)UI69 φ80 dlacZ ΔM15 | BRL Life Technologies Inc. |

| E. coli MH1 | MC1061 derivative; araD139 lacX74 galU galK hsr hsm+ strA | 7 |

| E. coli XL1-Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac (F′ proAB lacIqZΔM15 Tn10 [Tetr]) | Stratagene |

| B. campestris ATCC 43754 | Wild-type brochocin-C producer | American Type Culture Collection |

| C. piscicola LV17C | Plasmid free, brochocin-C sensitive | 2 |

| C. divergens LV13 | Wild-type divergicin A producer, brochocin-C sensitive | 40 |

| C. piscicola UAL26 | Plasmid free, produces uncharacterized bacteriocin, brochocin-C sensitive | Lab collection |

| Plasmids | ||

| pUC118 | lacZ′, 3.2 kb, Apr | 39 |

| pMG36e | 3.6 kb, Emr | 37 |

| pAP7.4 | pUC118 containing 4.4-kb EcoRI B. campestris chromosomal fragment, 7.6 kb, Apr | This study |

| pRW19e | pMG36e containing 514-bp dvnA-dviA fragment, 4.1 kb, Emr | 24 |

| pJKM19 | pRW19e containing 541-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment, dvn::brcA brcB brcI, 4.1 kb, Emr | This study |

| pJKM36 | pRW19e containing 388-bp HindIII-KpnI fragment, 4.1 kb, Emr | This study |

| pJKM46 | pRW19e containing 309-bp HindIII-KpnI, dvn::brcB brcI fragment, 4.0 kb, Emr | This study |

| pJKM49 | pMG36e containing 201-bp PstI-KpnI fragment, brcI, 3.8 kb, Emr | This study |

| pJKM53-1 | 292-bp XbaI-SacI PCR product from pJKM19 cloned in pUC118; dvn::brcA, Emr, 3.5 kb | This study |

| pJKM56 | 292-bp XbaI-SacI fragment from pJKM53-1 and 444-bp SacI-KpnI background chromosomal fragment cloned in XbaI and KpnI sites of pMG36e, dvn::brcA, Emr, 4.3 kb | This study |

| pJKM61 | 292-bp XbaI-SacI fragment from pJKM53-1 and 426-bp SacI-KpnI fragment from pJKM46 cloned in XbaI and KpnI sites of pUC118, dvn::brcA dvn::brcB brcI, Apr, 3.9 kb | This study |

| pJKM64 | 718-bp XbaI-KpnI fragment from pJKM61 cloned in pUC119, dvn::brcA dvn::brcB brcI, Apr, 3.9 kb | This study |

| pJKM67 | 718-bp XbaI-KpnI fragment from pJKM61 cloned in pMG36e, dvn::brcA dvn::brcB brcI, Emr, 4.3 kb | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Emr, erythromycin resistant; brcA, brochocin-C peptide A gene with truncated leader peptide; brcB, brochocin-C peptide B gene with truncated leader peptide; dvnA, divergicin A bacteriocin gene; dviA, divergicin A immunity gene; dvn::brcA, brochocin-C peptide A gene fused to DNA encoding divergicin A signal peptide; dvn::brcB, brochocin-C peptide B gene fused to DNA encoding divergicin A signal peptide; brcI, brochocin-C immunity gene.

Purification of brochocin-C.

Five liters of sterile CAA medium (14) with 2.5% glucose was inoculated with 2% of an overnight culture of B. campestris ATCC 43754 and grown at a constant pH of 6.7 with a Chemcadet controller (Cole-Parmer, Chicago, Ill.) for addition of filter-sterilized 2 N NaOH. Cells were removed by centrifugation at 8,500 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was extracted twice with 1.5 liters of n-butanol. The butanol fraction was diluted with water (1:1) and concentrated by vacuum evaporation at 35°C to remove all traces of butanol. The bacteriocin extract was precipitated with 1.7 liters of cold (−60°C) acetone and stored at 5°C for 24 h. The precipitate was separated by centrifugation (13,000 × g for 15 min), dissolved in 10 ml of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), loaded onto a Sephadex G-50 (Pharmacia) column (2.5 by 120 cm) which was preequilibrated with TFA, and eluted with 0.1% TFA at a flow rate of 0.6 ml min−1. Absorbance was monitored at 220 nm, and fractions showing antimicrobial activity by the spot-on-lawn assay (see below) were concentrated and lyophilized. Brochocin-C preparations were examined on 20% polyacrylamide gels (20). Electrophoresis was done with a 20-mA constant current for 3 h, and gels were fixed in 50% methanol–10% acetic acid for 1 h and stained with Coomassie blue (Bio-Rad) or assayed for antimicrobial activity by overlayering with Carnobacterium piscicola LV17C (Table 1) as described by Worobo et al. (40). The purity of the sample was confirmed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and by mass spectral analysis.

Bacteriocin assays and antibacterial spectrum of brochocin-C.

Determination of arbitrary activity units (AU) of bacteriocin per milliliter was based on the reciprocal of the greatest dilution of the concentrated bacteriocin solution that showed activity against Carnobacterium divergens LV13 (4). Inhibition of C. piscicola LV17C was examined by the addition of 100 AU of partially purified brochocin-C per ml to APT broth (pH 6.5) and to phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5) containing 106 CFU of the indicator organism per ml, to determine the bactericidal or bacteriostatic action of the bacteriocin. Viable counts were determined on APT agar at selected time intervals, and cell lysis was checked by monitoring the optical density at 600 nm. Antagonistic activity against a wide range of bacterial strains was determined by deferred-inhibition or spot-on-lawn assays (2) with partially purified brochocin-C at 100 and 800 AU of brochocin-C per ml determined against C. divergens LV13. For spot-on-lawn activity assays, strains of Carnobacterium, Enterococcus, Lactococcus, Leuconostoc, and Brochothrix were grown in APT broth; Lactobacillus and Pediococcus strains were grown in Lactobacilli MRS broth (Difco); Bacillus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus strains were grown in tryptic soy broth (Difco); and Listeria strains were grown in tryptic soy broth with 0.6% yeast extract. Strains of Clostridium botulinum and other Clostridium spp. were grown in Trypticase-peptone-glucose-yeast extract broth (TPGYE) (5% Trypticase, 0.5% peptone, 0.4% glucose, 2% yeast extract, pH 7.2) with 1% sodium thioglycolate added prior to use in bioassays. Spores of Bacillus spp. were prepared by growing the strains aerobically in GBBM (41), and spores of Clostridium spp. other than C. botulinum were prepared under anaerobic growth conditions in sporulation medium (SM) (5% Trypticase, 1% peptone, pH 7.2) (16). Inocula for C. botulinum were grown at 30°C for 24 h in Trypticase-peptone-glucose-yeast extract broth with 1% sodium thioglycolate added and were grown for spore production in SM with 1% sodium thioglycolate. For nonproteolytic strains, SM was supplemented with 0.2% glucose and 0.3% K2HPO4. Sporulation was monitored by phase-contrast microscopy. After 4 to 8 days, C. botulinum spores were harvested and washed 10 times by repeated centrifugation (16,300 × g for 10 min at 4°C) and resuspension in cold 0.85% NaCl. Spore crops were maintained at 4°C in 0.85% NaCl. Except for C. botulinum, germination of spores for inhibition studies was stimulated by heat shocking the spores of Bacillus and Clostridium spp. at 80°C for 30 min and 75°C for 15 min, respectively. Nonproteolytic strains of C. botulinum were heat shocked at 55°C for 15 min, and proteolytic strains were heat shocked at 80°C for 10 min. The concentration of spores inoculated into soft APT agar depended on the amount needed to produce a confluent lawn. The activity of brochocin-C against a wide range of gram-negative bacteria, and against E. coli ATCC 25922 and Salmonella choleraesuis ATCC 10708 in the presence of 20 mM EDTA, was also tested (32). Nisin (Aplin and Barrett, Ltd., Langford, United Kingdom) was used as a control according to the study of Stevens et al. (32). The stock solution of nisin (10 mg ml−1) was prepared in 0.02 N HCl, and it was used at 3,200 AU ml−1 (equivalent to 250 μg of nisin ml−1, as verified by using C. divergens LV13).

Activity and stability of brochocin-C.

B. campestris was grown in APT broth at 25°C for 18 to 24 h, cells were separated by centrifugation (8,500 × g for 15 min), and the supernatant was heated at 65°C for 30 min, cooled, and adjusted to pH 2 through 9 with either 5 N HCl or 5 N NaOH. The heat stability of the pH-adjusted supernatant was determined at 65°C for 30 min, 100°C for 15 min, or 121°C for 15 min by testing for residual activity by the spot-on-lawn assay against C. piscicola LV17C. The effect of proteolytic enzymes and organic solvents was determined with preparations of butanol-extracted brochocin-C. For stability in organic solvents, the bacteriocin preparation was diluted in 0.1% TFA, 95% ethanol, 100% methanol, or 100% acetonitrile to give an initial concentration of 10 AU μl−1. Samples were stored at 25 and 4°C for 6 and 24 h and tested for activity.

Determination of the amino acid sequence of brochocin-C.

The N-terminal amino acid sequence of purified brochocin-C was determined by the Alberta Peptide Institute (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada) by automated Edman degradation with a gas-phase sequencer (Applied Biosystems model 470A) with on-line phenylthiohydantoin-derivative identification by high-pressure liquid chromatography (Applied Biosystems model 120A chromatograph). The mass spectrum of purified brochocin-C was measured by electrospray ionization (Fisons Trio 2000 mass spectrometer; done by L. Hogg at the Plant Biotechnology Institute, National Research Council of Canada, Saskatoon, Canada). The sample was dissolved in acetonitrile-water (1:1) containing 1% formic acid and was loop injected (10 ml) at a flow rate of 6 ml min−1.

DNA isolation, manipulation, and hybridization.

Isolation of plasmids from B. campestris, E. coli, and carnobacteria was done as previously described (2, 29, 40). Preparation of chromosomal DNA from B. campestris grown (2% inoculum) in 40 ml of APT broth to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.6 was done as described by Quadri et al. (28). Standard methods were used for restriction enzyme digestion, ligations, gel electrophoresis, and E. coli transformation (29). Transformation of carnobacteria was done as described by Worobo et al. (40). T4 DNA ligase and restriction endonucleases were obtained from Boehringer-Mannheim (Dorval, Québec, Canada), Promega (Burlington, Ontario, Canada), and New England Biolabs (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Colony blots were done by standard methods (31), and DNA fragments were blotted by the method of Southern (31) onto Hybond N (Amersham Corp.) nylon membranes. A degenerate 23-mer oligonucleotide probe [APO-1, 5′-AAAGATATTGG(ATC)AAAGG(ATC)ATTGG-3′] based on residues 8 to 15 of the amino acid sequence of the active compound was used to locate the brochocin-C structural gene in both colony blot and Southern hybridizations. Oligonucleotides based upon derived nucleotide sequences were synthesized (Applied Biosystems 391 PCR Mate synthesizer), quantified, and used for hybridizations or as primers for nucleotide sequencing. DNA probes were radioactively end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) and T4 polynucleotide kinase (Promega) or were nonradioactively labeled by random-primed labeling with digoxigenin-dUTP (Boehringer-Mannheim).

Cloning of the brochocin gene.

Genomic DNA from B. campestris ATCC 43754 was digested with EcoRI. DNA fragments of 4.4 kb corresponding to the hybridization signal identified with APO-1 were isolated and purified from the gel. The resulting fragments were cloned into the EcoRI site of pUC118. E. coli DH5α transformants were screened by alpha-complementation (39), and colony blots were done to discriminate the white colonies for the correct DNA insert. Positive clones were digested with EcoRI and hybridized in a Southern blot with APO-1 to confirm the presence of the brochocin gene.

Nucleotide sequencing of plasmid DNA.

The nucleotide sequence was determined by Taq DyeDeoxy Cycle sequencing (Department of Biochemistry or Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta) on an Applied Biosystems model 373A sequencer by using the universal forward and reverse primers of pUC118. Site-specific 18-mer primers based on newly sequenced DNA were synthesized for further sequencing. Protein and nucleotide sequence analyses were performed with the DNASTAR software program (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, Wis.). Homology searching of proteins was based on the FASTA algorithm of Pearson and Lipman (26).

Construction of expression clones of brochocin-C.

To investigate the roles of the open reading frames (ORFs) designated brcA, brcB, and brcI (Fig. 1), several expression clones were constructed in E. coli and transformed into strains of carnobacteria. The expression clones were designed to create in-frame translational fusions of brcA and/or brcB with the nucleotide sequence encoding the divergicin A signal peptide (40). The nucleotide sequence of this signal peptide contains a HindIII restriction endonuclease site which cuts 10 nucleotides upstream of DNA encoding the signal peptide cleavage site (40). Two primers, JMc10 (5′-CCCAAGCTTCTGCTTACAGTTCAAAAGATTGTCTA-3′) and JMc29 (5′-GCGAAGCTTCTGCTAAAATAAATTGGGGAAATG-3′), were designed to facilitate this fusion. The first 14 nucleotides of each primer regenerated the HindIII site (underlined) of the signal peptide as well as the additional amino acids (Ala-Ser-Ala) of the cleavage site. The remaining nucleotides of each primer are complementary to the 5′ ends of the nucleotide sequences encoding the mature portions of the brcA and brcB gene products, respectively (Fig. 1). The primers JMc11 (5′-CCCGGTACCTTTGTGCTAGTTAGAGAATAT-3′) and JMc17 (5′-CCCGGTACCATAGTTTTTACCATTGATCCC-3′) are based on the 3′ ends of brcI (Fig. 1) and brcB, respectively, and both contain KpnI restriction sites (underlined). To construct plasmid pJKM19 (Fig. 2), DNA was amplified from pAP7.4 by using the primers JMc10 and JMc11 and cloned into the HindIII and KpnI sites of pRW19e. Plasmids pJKM36 and pJKM46 (Fig. 2) were constructed in a manner similar to that for pJKM19 except that the primers used in the PCR were JMc10-JMc17 and JMc11-JMc29, respectively. An expression clone containing only brcI was constructed as follows. DNA from pAP7.4 was amplified by using JMc11 and JMc28 as primers and cloned into the EcoRI and KpnI sites of pUC118. The primer JMc28 (5′-CGCGAATTCATCGGAAGTATTTGGGATC-3′) is based on the 5′ end of brcI and contains an EcoRI restriction site (underlined). The fragment was subsequently excised from pUC118 with PstI and KpnI and cloned into these sites in pMG36e to create pJKM49 (Fig. 2). The forward primer JMc25 (5′-CGCTCTAGATGGAGGTTGGTATATATG-3′) and reverse primer JMc30 (5′-CGCGAGCTCCTAGTTACCTAATAATCC-3′) contained XbaI and SacI sites (underlined), respectively, and were designed to amplify the dvn::brcA gene fusion from pJKM19. The resulting PCR product was cloned into the XbaI and SacI sites of pUC118 to give pJKM53-1. The two inserts from pJKM53-1 and pJKM46 were excised and ligated into the XbaI and KpnI sites of pUC118 and pUC119 to create pJKM61 and pJKM64, respectively (Fig. 2). The 718-bp fragment from pJKM61 was excised and cloned into pMG36e in C. piscicola UAL26 to give plasmid pJKM67 (Fig. 2). DNA amplifications were performed with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer, Foster City, Calif.) or Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by the suppliers’ recommended procedures. All PCR products were sequenced to confirm the absence of mutations.

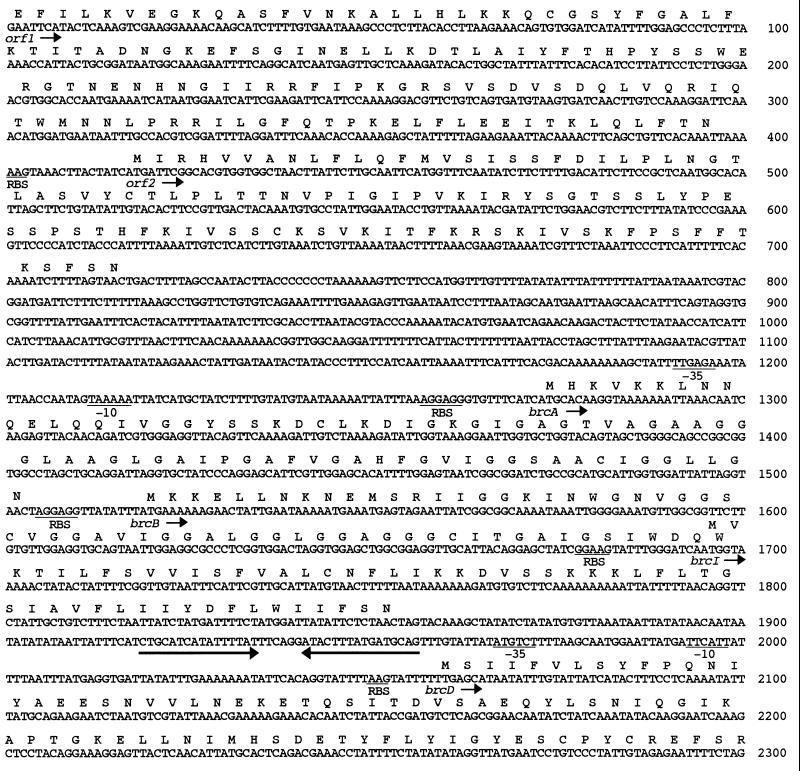

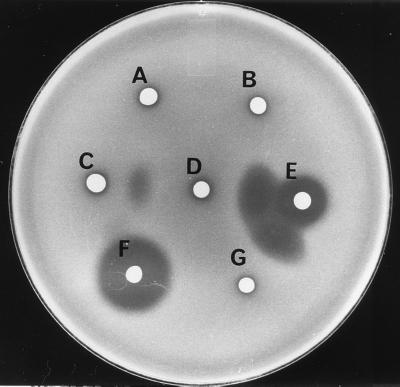

FIG. 1.

Single-strand DNA sequence of the 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment of pAP7.4 containing the brochocin-C operon. The brochocin-C structural (brcA and brcB), immunity (brcI), and putative transport (brcD and brcT) genes as well as orf1 and orf2 are shown, with the translation products given above the nucleotide sequence. Potential RBSs and putative −35 and −10 regions are indicated. An inverted repeat with the potential to function as a transcription terminator is indicated by converging arrows.

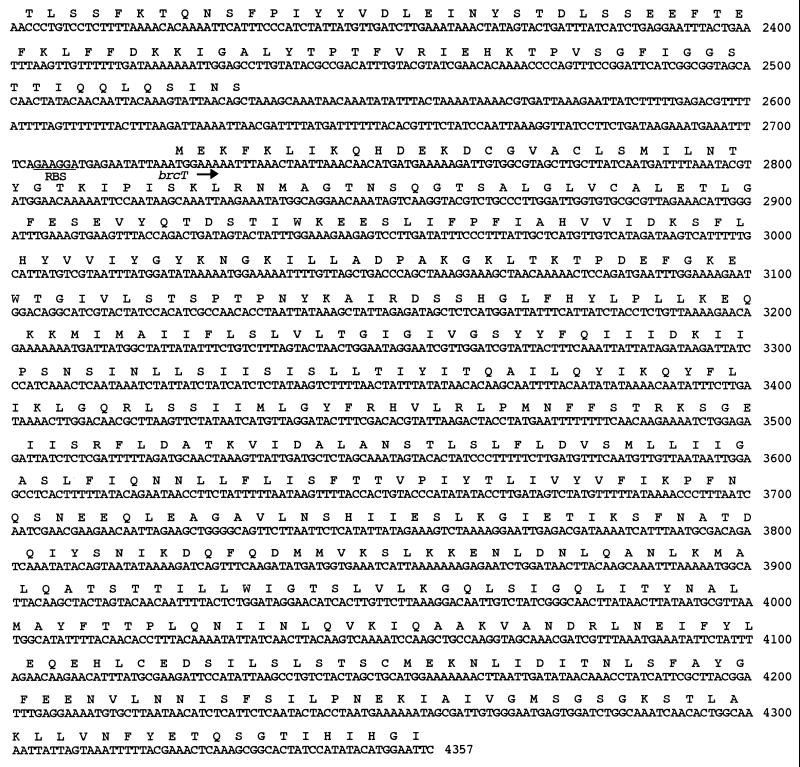

FIG. 2.

Genetic organization of the 4.4-kb EcoRI fragment encoding the brochocin-C operon and various expression clones. pJKM19, pJKM36, and pJKM46 were constructed in pRW19e to create the gene fusion with the divergicin A signal peptide. pJKM49, pJKM56, and pJKM67 were constructed by cloning the appropriate fragments in pMG36e. pJKM61 and pJKM64 were constructed by cloning the appropriate fragments in pUC118 and pUC119, respectively. Promoters controlling the expression of each plasmid are shown.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported here has been submitted to GenBank and given accession no. AF075600.

RESULTS

Inhibitory spectrum of B. campestris.

Purification of brochocin-C yielded stock supplies with 25,600 AU of brochocin-C per ml. This was diluted to give solutions with 100 or 800 AU ml−1 (based on its activity against C. divergens LV13) for use in spot-on-lawn assays. As shown in Table 2, deferred-inhibition and spot-on-lawn tests with 800 AU of brochocin-C per ml gave the best and almost equivalent inhibitory spectra. Brochocin-C was also active against vegetative cells and spores of strains of Bacillus and Clostridium spp. Siragusa and Nettles Cutter (30) did not detect activity against seven strains of gram-negative bacteria. Similarly, no inhibition was observed against 29 strains of gram-negative bacteria, including Aeromonas hydrophila, Citrobacter spp., Enterobacter spp., E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Salmonella (10 serovars), Serratia spp., Shewanella putrefaciens, Shigella flexneri, and Yersinia enterocolitica, as well as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Pseudomonas fragi. Treatment of E. coli ATCC 25922 and S. choleraesuis ATCC 10708 with EDTA and nisin resulted in 4.0- and 2.1-log-unit reductions in the bacterial count, respectively. In the presence of brochocin-C and EDTA, there were 2.8- and 2.3-log-unit reductions, respectively. Brochocin-C was active in deferred-inhibition assays against the spores of seven proteolytic and three nonproteolytic strains of C. botulinum, but only limited inhibition against the vegetative cells was observed.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory spectrum of brochocin-C

| Target species | No. of strains | No. inhibited in:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deferred inhibition test | Spot-on-lawn test with:

|

|||

| 100 AU ml−1 | 800 AU ml−1 | |||

| Bacillus spp. | 7 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| Bacillus spp. (spores) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Brochothrix spp. | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Carnobacterium spp. | 19 | 18 | 17 | 18 |

| Clostridium spp. | 8 | 4 | 3 | 7a |

| Clostridium spp. (spores) | 7 | 6 | 1 | 7a |

| C. botulinum | 12 | 7 | NTb | NT |

| C. botulinum (spores) | 12 | 10 | NT | NT |

| Enterococcus spp. | 16 | 16 | 10 | 14 |

| Lactobacillus spp. | 22 | 19 | 3 | 11 |

| Lactococcus spp. | 9 | 9 | 0 | 4 |

| Leuconostoc spp. | 12 | 12 | 1 | 11 |

| Listeria spp. | 42 | 42 | 0 | 39 |

| Pediococcus spp. | 6 | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| Staphylococcus spp. | 17 | 5 | 0 | 15 |

| Streptococcus spp. | 8 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Gram-negative bacteria | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

1,600 AU ml−1 was used.

NT, not tested.

Production and characteristics of brochocin-C.

B. campestris ATCC 43754 grown in APT broth at 25°C with an initial inoculum of 107 CFU ml−1 and a starting pH of 6.5 resulted in detectable bacteriocin production within 3 h. Maximum bacteriocin production was detected in the stationary phase after 30 h of incubation. The pH when the population of B. campestris ATCC 43754 was maximal was 5.0, and bacteriocin activity remained stable for up to 48 h at 25°C (data not shown). Growth in semidefined CAA medium (pH 6.5) without pH adjustment resulted in a fourfold decrease in the maximum level of bacteriocin produced compared with production in APT broth. However, in CAA medium maintained at constant pH 7.0 with 2 N NaOH throughout the growth period, there was a fivefold increase in bacteriocin production and a 1-log-unit increase in the maximum cell density. Brochocin-C from supernatants of B. campestris was thermally stable from pH 2 to 9 when heated at 100°C for 15 min. After 1 week of storage at 4°C, samples heated at 100°C for 15 min still showed the same levels of bacteriocin activity. After heating at 121°C for 15 min, there was a decrease in bacteriocin activity from 1,600 to 200 AU ml−1 at pH 9.0 and from 3,200 to 400 AU ml−1 at pH 8, but at all other pH levels (2 to 7), the activity loss was not greater than 75%. Partially purified (butanol-extracted) brochocin-C added at 100 AU ml−1 to APT broth (pH 6.5) and to phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.5) containing C. piscicola LV17C at 106 CFU ml−1 was bacteriostatic in APT broth but bactericidal in phosphate buffer. There was no change in optical density, which suggests that brochocin-C is not bacteriolytic to C. piscicola LV17C. The proteinaceous nature of butanol-extracted brochocin-C (6,400 AU ml−1) was demonstrated by inactivation with papain, pepsin, pronase E, subtilisin, trypsin, and α-chymotrypsin added at 1 mg ml−1, similar to results of previous work (30). Activity was not lost in the presence of catalase or lipase. Butanol-extracted brochocin-C added to organic solvents at 10 AU μl−1 and stored at 25 and 4°C was least stable in acetonitrile at 25°C, but it was relatively stable at 4°C. Brochocin-C activity was not affected by ethanol and 0.1% TFA after 24 h of storage at either temperature. A moderate loss of activity in methanol was observed.

Purification of brochocin-C.

A 5-liter fermentation culture of B. campestris ATCC 43754 grown in CAA medium for 22 h at constant pH 6.7 was used for purification of the active compound. This compound was extracted from the supernatant by butanol extraction, acetone precipitation, and size exclusion chromatography (Table 3). Staining of the gel after sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis showed only one band that correlated with a zone of inhibition that was observed when the gel was overlayered with C. piscicola LV17C (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Purification of brochocin-C

| Purification stage | Vol (ml) | Activity (AU ml−1) | Total activity (AU) | Protein concn (mg ml−1)a | Sp act (AU mg−1) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant | 3,000 | 3,200 | 9.6 × 106 | 1.197 | 2.67 × 103 | 100 |

| Butanol extraction | 100 | 51,200 | 5.1 × 106 | 3.155 | 1.62 × 104 | 53 |

| Acetone precipitation | 20 | 204,800 | 4.1 × 106 | NDb | ND | 43 |

| Sephadex G50 | 8 | 51,200 | 4.1 × 105 | 0.085 | 6.02 × 105 | 4.3 |

Determined by the method of Lowry et al. (21) with bovine serum albumin as a standard.

ND, not determined.

Genetic characterization of brochocin-C.

Biochemical and genetic information revealed that brochocin-C was a two-peptide bacteriocin (BrcA and BrcB) and that we had purified BrcA. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of BrcA was determined by automated Edman degradation. This revealed the first 48 amino acid residues from the N terminus: YSSKDCLKDIGKGIGAGTVAGAAGGGLAAGLGAIPGAFVGAHF GVIGG. The molecular weight determined by mass spectrometry was 5,241.2 ± 1.2. The structural gene corresponding to the purified BrcA was identified by both colony blot and Southern hybridizations. Plasmid and genomic DNAs from B. campestris were digested with EcoRI, blotted onto a nylon membrane, and hybridized with the labeled probe APO-1 at 29°C. Unique bands of the plasmid and the genomic DNA digests gave hybridization signals (data not shown). Increasing the stringency of hybridization resulted in loss of the signal for both plasmid and genomic DNAs. Cloning and sequencing of the 1.6-kb EcoRI DNA fragment from the plasmid DNA that hybridized to APO-1 revealed that this was nonspecific hybridization (data not shown).

Subsequently, a 4.4-kb chromosomal DNA fragment that hybridized to APO-1 was detected. This fragment was cloned into the EcoRI site of pUC118 to create pAP7.4. The nucleotide sequence of the 4.4-kb fragment of pAP7.4 is shown in Fig. 1. This revealed the sequence corresponding to APO-1 within an ORF corresponding to the structural gene (brcA) of BrcA and consisted of 231 bp encoding a primary translation product of 77 amino acid residues. The translation product of the brcA gene contained all 48 of the N-terminal amino acids of BrcA previously identified by N-terminal amino acid sequencing. The sequence indicated that there would be cleavage of the polypeptide chain to release an 18-amino-acid leader peptide and a 59-amino-acid mature bacteriocin. The leader peptide closely resembled the double-glycine-type leader peptides that are found in many class II bacteriocins (9, 15, 18). At positions −4, −7, −12, and −15 of the leader peptide there are the hydrophobic residues and at position −8 there is the highly conserved glutamic acid residue that are characteristic of leader peptides of class II bacteriocins (9, 15). A putative promoter and a ribosome binding site (RBS) were detected upstream of this structural gene. The molecular weight of the mature BrcA product identified by nucleotide sequencing was calculated to be 5,245, which is in good agreement with the mass spectrometry result if two cysteines in the molecule form a disulfide bridge. The uncertainty about the cysteine residue at position 6 from the results of Edman degradation was resolved by nucleotide sequencing of the gene; a second cysteine residue was found at position 52 of the peptide. The difference between the calculated and determined (5,241.2 ± 1.2) molecular weights indicates a disulfide link between the two cysteines, as has been observed for a number of other class II bacteriocins (18).

Directly downstream of brcA there is a second ORF, brcB, that is preceded by an RBS. The translation product of this ORF starts with a sequence of 17 amino acids that resembles a probable leader peptide of the double-glycine type. There are hydrophobic residues similar to those in BrcA at positions −4, −7, and −12, as well as a glutamic acid residue at position −8. The leader sequence is followed by 43 amino acid residues that could constitute the second peptide of a two-component bacteriocin. Hydropathy plots (19) of the mature BrcA and BrcB peptides showed a charged N terminus, but otherwise the peptides were strongly hydrophobic (data not shown). A homology search in the data bank revealed that the mature peptides BrcA and BrcB have 59 and 49% identity with ThmA and ThmB, respectively, which together form the two-component bacteriocin thermophilin 13 from Streptococcus thermophilus (22).

A third ORF, brcI, with an RBS was detected downstream of and overlapping the 3′ end of brcB. This suggests the possibility of translational coupling (1). The translation product of brcI would contain 53 amino acid residues and does not contain a double-glycine-type leader peptide. BrcI showed 21% identity to the translation product of ORFC, which is located immediately downstream of the structural gene for ThmB (22). The ORFC product had 59% similarity with BrcI when conserved amino acid substitutions were included. The similarities between BrcI and the ORFC product do not relate to specific regions of the proteins but occur generally over the entire molecules. Downstream of brcI is an imperfect inverted repeat that might function as a rho-independent terminator. This palindromic structure is followed by a putative promoter sequence and two ORFs, brcD and brcT, that encode proteins that resemble dedicated transport proteins found for other class II bacteriocins, such as lactococcin A, pediocin PA-1, and leucocin A (23, 33, 35). brcD encodes a polypeptide of 158 amino acids. A homology search in the GenBank database revealed that it had 24% identity and, when conserved residue substitutions are considered, 56% similarity with PedC, the accessory protein involved in the secretion of pediocin PA-1 (23). The 3′ end of the brcT gene is truncated due to the location of the EcoRI site used to clone this fragment. The translational product of the 5′ end of brcT showed the highest homology with the cbnT product, the ABC transporter of carnobacteriocin B2 (49% identity), indicating that BrcT belongs to the family of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters (27). Two ORFs (designated orf1 and orf2) were located upstream of the brcABIDT gene cluster. The translational product of 132 amino acids from the 5′-end-truncated orf1 shows 41% identity to ISAS30, a transposase from Aeromonas salmonicida that belongs to the IS30 family of insertion sequence elements (13). The polypeptide of 100 amino acids encoded by orf2 has a hydrophobic N terminus and a pI of 10 and shows no similarity to any known proteins.

Expression of BrcA and BrcB in heterologous hosts.

Previous work established that class II bacteriocins could be produced in lactic acid bacteria by replacing the double-glycine-type leader with a signal peptide to allow for export of active bacteriocin via the general protein secretory pathway (24). By using this strategy, expression clones were constructed to examine the roles of brcA and brcB individually or in combination. All of these constructs were based on the expression vector pMG36e (Table 1), and transcription was under control of the lactococcal P32 promoter. The signal peptide used in these constructs was from divergicin A (40).

To examine the extracellular role of the brcA gene product, a truncated brcA gene lacking the nucleotide sequence encoding the double-glycine-type leader peptide was fused to DNA encoding the divergicin A signal peptide of pRW19e. The resulting plasmid, pJKM19, also contained intact brcB and brcI genes. When C. divergens LV17C containing pJKM19 was analyzed by the deferred-inhibition assay, a zone of inhibition against C. divergens LV17C containing pMG36e was evident (Fig. 3). Similar results were obtained with C. piscicola LV13 (data not shown). A zone of inhibition was detected from these clones, and it was initially attributed to the activity of secreted BrcA, because the BrcB peptide would not be exported in the absence of dedicated transport proteins, although the brcB gene is present in this construct. pJKM36 was constructed in a manner similar to that for pJKM19 except that it lacked the brcI gene (Fig. 2). Strains containing pJKM36 produced a zone of inhibition similar to that of strains containing pJKM19; however, these clones grew poorly, and when used as indicators, immunity to brochocin-C was not expressed (data not shown). This indicated that the product of the brcI gene was most probably involved in immunity.

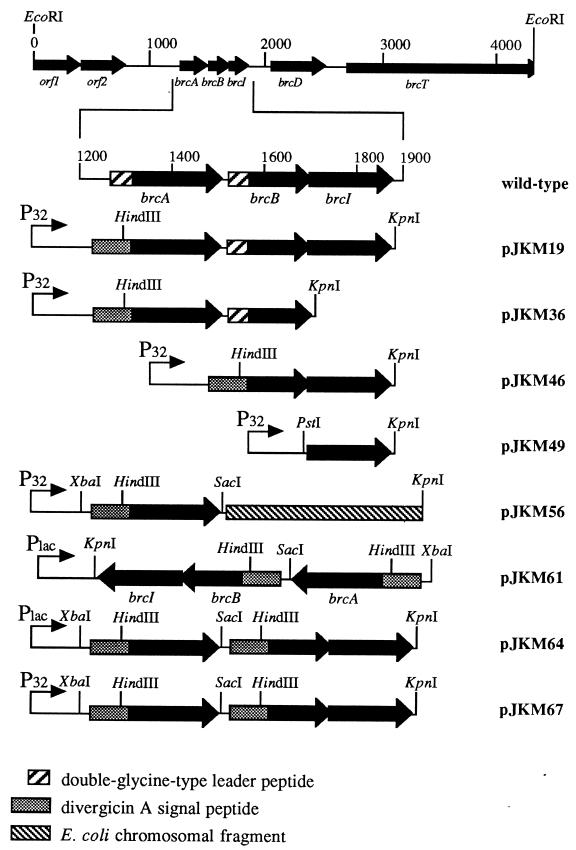

FIG. 3.

Bacteriocin activity and extracellular complementation of the BcrA and BcrB peptides from the brochocin-C bacteriocin. Producers are C. divergens LV17C containing pJKM49 (A), pMG36e (B), pJKM56 (C), pJKM46 (D and G), pJKM19 (E), and pJKM67 (F). C. divergens LV17C containing pMG36e was used as the indicator.

To examine the extracellular role of the brcB gene product, pJKM46, which lacked the brcA gene but had the nucleotide sequence encoding the double-glycine-type leader peptide of brcB replaced with the nucleotides encoding the divergicin A signal peptide, was constructed. This product also contained intact brcI (Fig. 2). No inhibition by strains containing pJKM46 was detected (Fig. 3). However, when the two clones containing pJKM19 and pJKM46 were grown adjacent to one another in a deferred-inhibition assay, the zone of inhibition was enhanced in the overlapping areas (Fig. 3). Enhancement of the antibacterial activity of strains containing pJKM19, with strains containing pMG36e as a control, did not occur (Fig. 3). These results indicated that extracellular complementation of both peptides is required for activity of the brochocin-C complex. An expression clone, pJKM49, containing only brcI was constructed to confirm the role of this gene in immunity to brochocin-C (Fig. 2). Zones of inhibition were not produced from C. divergens LV13 or C. piscicola LV17C containing pJKM49, but when these strains were used as indicators, partial immunity against brochocin-C was restored (data not shown); however, when C. divergens LV13 or C. piscicola LV17C containing pJKM19 or pJKM46 was used as an indicator strain, full immunity was expressed (data not shown).

To construct a plasmid for the expression of both BrcA and BrcB, as well as expression of immunity, the dvn::brcA gene was cloned into the XbaI and SacI sites of pUC118 to create pJKM53-1. By using these same restriction sites, the dvn::brcA insert was excised from pJKM53-1, and the fragment containing dvn::brcB and brcI from pJKM46 was excised by using XbaI and KpnI. Attempts to ligate both fragments into pMG36e digested with SacI and KpnI were unsuccessful. However, a plasmid, pJKM56 (Fig. 2), which contained the dvn::brcA-containing fragment and a 444-bp fragment that was found to be chromosomal DNA from E. coli (data not shown) was constructed. In contrast to C. piscicola LV17C containing pJKM19, C. piscicola LV17C containing pJKM56 did not produce a zone of inhibition (Fig. 3). When it was placed adjacent to C. piscicola LV17C containing pJKM46, a zone of inhibition was seen between the two colonies, indicating that extracellular complementation had occurred (Fig. 3). The zones of inhibition from transformants containing pJKM19 were likely due to the presence of the brcB gene. Similar results were seen when C. piscicola LV13 was transformed with pJKM56 (data not shown). These results showed that, under these conditions, neither of the peptides alone had antimicrobial activity and that full bacteriocin activity required the presence of both peptides.

Failure to generate an expression plasmid in E. coli that contained both dvn::brcA and dvn::brcB indicated that this construct was probably toxic to E. coli. The two inserts from pJKM53-1 and pJKM46 were ligated into the XbaI and KpnI sites of pUC118 to create pJKM61 (Fig. 2). The brochocin-C genes are in reverse orientation to the lac promoter in this construct. When this fragment was excised from pJKM61 with XbaI and KpnI and cloned into pUC119, induction with IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was lethal to the resulting E. coli XL1-Blue transformants containing pJKM64. The insert from pJKM61 was excised and cloned into pJMG36e by transforming the ligation mixture into C. piscicola UAL26, giving plasmid pJKM67. Transformants containing pJKM67 produced zones of inhibition when overlayered with C. piscicola UAL26 containing pMG36e. However, when they were overlayered with C. piscicola UAL26 containing pJKM19 or pJKM46, both of which contain the brochocin-C immunity gene, zones of inhibition were no longer present (data not shown). Plasmid pJKM67 was used to transform C. piscicola LV17C, and all of the transformants produced zones of inhibition similar to that of C. piscicola UAL26 containing pJKM67 (Fig. 3).

DISCUSSION

Brochocin-C is a two-peptide class IIb bacteriocin (18) with a broad spectrum that compares favorably with the antibacterial spectrum of nisin, inhibiting the outgrowth of Bacillus and Clostridium spores, including spores of C. botulinum. This is exceptional because the structure of brochocin-C is not comparable to that of nisin. Nisin does not require a receptor to permeabilize the membranes of sensitive cells, and it inhibits gram-negative bacteria pretreated with EDTA (32). Brochocin-C was also active against E. coli and S. choleraesuis cells treated with EDTA, although the degree of inhibition that we observed for nisin and brochocin-C was less than that reported for nisin by Stevens et al. (32). This suggests that brochocin-C also does not require a receptor to be active. Plasmid pJKM64 is lethal in E. coli when Sec-dependent production of brochocin-C is introduced, and this provides further evidence that brochocin-C is active in E. coli and does not need a receptor. Thermophilin 13 is a bacteriocin that is very similar in structure to brochocin-C, and it was shown to dissipate the proton motive force in liposomes, indicating that a receptor is not required for activity of this bacteriocin (22).

In addition to the heat stability of brochocin-C at 100°C previously reported by Siragusa and Nettles Cutter (30), we showed that activity is maintained from pH 2 to 9 with heating at 100°C. These characteristics make brochocin-C worth studying for its potential as a food preservative. B. campestris ATCC 43754 was isolated as a soil microorganism (34), and it can be assumed to be present in meats based only on its close relationship to B. thermosphacta. The only traits that separate these two species are that B. thermosphacta grows in the presence of and reduces 0.05% potassium tellurite and that B. campestris hydrolyzes hippurate and produces acid from rhamnose. Also, B. thermosphacta grows in media containing up to 10% NaCl. Because of its similarities to B. thermosphacta and its relatively recent description (34), it is possible that strains of B. campestris were previously misidentified as B. thermosphacta.

Attempts to purify brochocin-C by the method described for leucocin A (14) proved unsuccessful because large losses in activity occurred after passage over the Amberlite XAD-8 hydrophobic interaction column and reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography with a C18 column (data not shown). A gradient of 0.1% TFA with acetonitrile did not give discernible peaks associated with the biologically active fractions. Siragusa and Nettles Cutter (30) reported that the compound was partially purified by ammonium sulfate fractionation; however, in our study, ammonium sulfate precipitation produced a floating film that contained a significant amount of activity, similar to the phenomenon encountered with lactacin F (25). Purification of BrcA was achieved with butanol extraction of the supernatant fluids and size exclusion chromatography.

Following N-terminal amino acid sequencing of the pure compound, an appropriate oligonucleotide probe that gave an intense hybridization signal with B. campestris plasmid DNA was synthesized, leading to the nucleotide sequencing of the 1.6-kb EcoRI fragment associated with the signal, but the BrcA structural gene was not located on this fragment. The false-positive signal might be attributed to a higher copy number of plasmid DNA with a remotely similar sequence, compared with the single copy of the structural gene on the chromosome. The genomic DNA fragment that hybridized to the probe was subsequently cloned, its nucleotide sequence was determined, and an ORF corresponding to the structural gene for BrcA was found. The amino acid sequence corresponding to the purified BrcA peptide was typical of double-glycine-type leader peptides of class II bacteriocins (9, 15, 18). The second ORF detected directly downstream of the BrcA structural gene encoded a 60-amino-acid peptide which contained a putative 17-amino-acid double-glycine-type leader peptide. The double-glycine-type leader peptides are required to direct secretion of bacteriocins by dedicated ABC transporters that are cleaved after the double glycine residues to release the mature peptides (36). Using the results of our previous work (24), we showed that by fusing the signal peptide of divergicin A in place of the double-glycine-type leader peptides, secretion of separate components was achieved by use of the Sec-dependent export pathway. This demonstrated the two-component nature of brochocin-C.

Individually, transformants of carnobacteria producing either the BrcA or the BrcB peptide were not active against the indicators tested in this study, because both components are required for activity of the bacteriocin complex. The reason why purified BrcA peptide showed antibacterial activity might be that small amounts of contaminating BrcB are present in the purified BrcA sample due to the hydrophobic nature of the peptides. It is also possible that high concentrations of BrcA have antimicrobial activity, as shown for high concentrations of ThmA (22). This would be similar to the two-component bacteriocin lactacin F from Lactobacillus johnsonii. LafA is active against one of six strains normally sensitive to the lactacin F bacteriocin (3). When expressed individually, the second component of this bacteriocin (LafX) lacked activity; however, when LafX was concentrated, antimicrobial activity was detected. It remains unclear why transformants containing pJKM19 showed antimicrobial activity. One explanation might be that the strains of carnobacteria used in this study contain chromosomally encoded transport proteins homologous to the dedicated transport proteins of brochocin-C that are responsible for the secretion of BrcB. Heterologous bacteriocin production by secretion proteins encoded on the chromosome has also been described for L. lactis IL1403 (38). It is also possible that zones of inhibition produced by transformants containing pJKM19 resulted from leakage of unprocessed BrcB from lysed cells, which would complement BrcA for antimicrobial activity.

The third ORF (brcI) encodes the immunity protein for brochocin-C. This gene encodes a 53-amino-acid protein, and its expression alone from pJKM49 restored some immunity but not to wild-type levels. However, both of the expression clones pJKM19 and pJKM46 restored full immunity. The overlap of the 3′ end of brcB with the 5′ end of brcI hints at the possibility of translational coupling between these two genes (1). This model suggests that when translation terminates, the ribosome either may dissociate from the mRNA or may scan the mRNA in both upstream and downstream directions to reinitiate translation in response to an encounter with a functional start site. The RBS of brcI (GGAAG) is atypical in that it lies 12 nucleotides upstream of the ATG initiation codon. The brcI gene in pJKM49 may not be transcribed as efficiently as those in pJKM19 and pJKM46, explaining the partial immunity to brochocin-C of strains containing this plasmid. Downstream of the immunity gene, two genes were found, brcT and brcD, that most likely encode the dedicated transport apparatus for brochocin-C. The putative accessory transport protein for brochocin-C, BrcD, is homologous to the accessory protein (PedC) for pediocin PA-1/AcH. These two proteins are generally smaller than accessory proteins for other class II bacteriocins, i.e., 158 versus 450 amino acids (6, 23). Furthermore, brcD preceeds the gene for the putative ABC transporter protein, brcT, as reported for pediocin PA-1/AcH (6, 23).

Despite its broad spectrum of activity and potency, further research is required to determine the potential of brochocin-C for use in food systems. For example, it is necessary to determine whether this bacteriocin is inactivated by proteolytic enzymes in foods and whether it is bound to and inactivated by other food constituents. A key requirement for use of brochocin-C in foods is a means of effectively delivering the bacteriocin. Even if brochocin-C production in a gene cassette in a food grade organism proves unsuccessful for meat preservation, this system could also serve as a model for protein engineering of other class II bacteriocins in food systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the technical advice given by Randy Worobo and Lynn Elmes.

This research was funded by a strategic grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adhin M R, van Duin J. Scanning model for translational reinitiation in eubacteria. J Mol Biol. 1990;213:811–818. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80265-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahn C, Stiles M E. Plasmid-associated bacteriocin production by a strain of Carnobacterium piscicola from meat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2503–2510. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2503-2510.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison G E, Fremaux C, Klaenhammer T R. Expansion of bacteriocin activity and host range upon complementation of two peptides encoded within the lactacin F operon. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2235–2241. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2235-2241.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barefoot S F, Klaenhammer T R. Detection and activity of lactacin B, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:1808–1815. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.6.1808-1815.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blickstad E, Molin G. Growth and end-product formation in fermenter cultures of Brochothrix thermosphacta ATCC 11509 and two psychrotrophic Lactobacillus spp. in different gaseous atmospheres. J Appl Bacteriol. 1984;57:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1984.tb01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bukhtiyarova M, Yang R, Ray B. Analysis of the pediocin AcH gene cluster from plasmid pSMB74 and its expression in a pediocin-negative Pediococcus acidilactici strain. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3405–3408. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3405-3408.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casadaban M J, Cohen S N. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1980;138:179–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90283-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delves-Broughton J. Nisin and its uses as a food preservative. Food Technol. 1990;44(11):100. , 102, 104, 106, 108, 111, 112, 117. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fremaux C, Ahn C, Klaenhammer T R. Molecular analysis of the lactacin F operon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3906–3915. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3906-3915.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner G A. Brochothrix thermosphacta (Microbacterium thermosphactum) in the spoilage of meats: a review. In: Roberts T A, Hobbs G, Christian J H B, Skovgaard N, editors. Psychrotrophic microorganisms in spoilage and pathogenicity. Toronto, Canada: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 139–173. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grau F H. Inhibition of the anaerobic growth of Brochothrix thermosphacta by lactic acid. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;40:433–436. doi: 10.1128/aem.40.3.433-436.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grau F H. Substrates used by Brochothrix thermosphacta when growing on meat. J Food Prot. 1988;51:639–642. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-51.8.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gustafson C E, Chu S, Trust T J. Mutagenesis of the paracrystalline surface protein array of Aeromonas salmonicida by endogenous insertion elements. J Mol Biol. 1994;237:452–463. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hastings J W, Sailer M, Johnson K, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Characterization of leucocin A-UAL 187 and cloning of the bacteriocin gene from Leuconostoc gelidum. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7491–7500. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.23.7491-7500.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Håvarstein L S, Holo H, Nes I F. The leader peptide of colicin V shares consensus sequences with leader peptides that are common among peptide bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria. Microbiology. 1994;140:2383–2389. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-9-2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health Protection Branch, Health and Welfare Canada. Compendium of analytical methods. Official methods of microbiological analysis of Foods. 1 to 4. Ottawa, Canada: Polyscience Publications Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henning S, Metz R, Hammes W P. Studies on the mode of action of nisin. Int J Food Microbiol. 1986;3:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klaenhammer T R. Genetics of bacteriocins produced by lactic acid bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:39–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kyte J, Doolittle R F. A simple method for displaying the hydropathic character of a protein. J Mol Biol. 1982;157:105–132. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90515-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:256–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marciset O, Jeronimus-Stratingh M C, Mollet B, Poolman B. Thermophilin 13, a nontypical antilisterial poration complex bacteriocin, that functions without a receptor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14277–14284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marugg J D, Gonzalez C F, Kunka B S, Ledeboer A M, Pucci M J, Toonen M Y, Walker S A, Zoetmulder L C M, Vandenbergh P A. Cloning, expression, and nucleotide sequence of genes involved in the production of pediocin PA-1, a bacteriocin from Pediococcus acidilactici PAC1.0. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2360–2367. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2360-2367.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCormick J K, Worobo R W, Stiles M E. Expression of the antimicrobial peptide carnobacteriocin B2 by a signal peptide-dependent general secretory pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4095–4099. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4095-4099.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muriana P M, Klaenhammer T R. Purification and partial characterization of lactacin F, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus acidophilus 11088. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:114–121. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.114-121.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pearson W R, Lipman D J. Improved tools for biological sequence comparison. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2444–2448. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.8.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quadri L E N, Kleerebezem M, Kuipers O P, de Vos W M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Characterization of a locus from Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B involved in bacteriocin production and immunity: evidence for global inducer-mediated transcriptional regulation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6163–6171. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.19.6163-6171.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Quadri L E N, Sailer M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. Chemical and genetic characterization of bacteriocins produced by Carnobacterium piscicola LV17B. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12204–12211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siragusa G R, Nettles Cutter C. Brochocin-C, a new bacteriocin produced by Brochothrix campestris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2326–2328. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2326-2328.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens K A, Sheldon B W, Klapes N A, Klaenhammer T R. Nisin treatment for inactivation of Salmonella species and other gram-negative bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:3613–3615. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.12.3613-3615.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoddard G W, Petzel J P, van Belkum M J, Kok J, McKay L L. Molecular analysis of the lactococcin A gene cluster from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis WM4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1952–1961. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.6.1952-1961.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talon R, Grimont P A D, Grimont F, Gasser F, Boeufgras J M. Brochothrix campestris sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Belkum M J, Stiles M E. Molecular characterization of genes involved in the production of the bacteriocin leucocin A from Leuconostoc gelidum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3573–3579. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.10.3573-3579.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Belkum M J, Worobo R W, Stiles M E. Double-glycine-type leader peptides direct secretion of bacteriocins by ABC transporters: colicin V secretion in Lactococcus lactis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1293–1301. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3111677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van de Guchte M, van der Vossen J M B M, Kok J, Venema G. Construction of a lactococcal expression vector: expression of hen egg white lysozyme in Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:224–228. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.1.224-228.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Venema K, Dost M H R, Beun P A H, Haandrikman A J, Venema G, Kok J. The genes for secretion and maturation of lactococcins are located on the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis IL1403. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1689–1692. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.5.1689-1692.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vieira J, Messing J. The pUC plasmids, an M13mp7-derived system for insertion mutagenesis and sequencing with synthetic universal primers. Gene. 1982;19:259–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(82)90015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Worobo R W, van Belkum M J, Sailer M, Roy K L, Vederas J C, Stiles M E. A signal peptide secretion-dependent bacteriocin from Carnobacterium divergens. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3143–3149. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.11.3143-3149.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young I E, Fitz-James P C. Chemical and morphological studies of bacterial spore formation. II. Spore and parasporal protein formation in Bacillus cereus var. alesti. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 1959;6:483–498. doi: 10.1083/jcb.6.3.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]