INTRODUCTION

The coronavirus pandemic has closed schools nationwide, and educational websites are an important component of the remote learning experience. Engaging, educational websites are also useful for parents in search of quality digital media to occupy their children while social distancing at home. However, many popular educational websites are advertisement (ad)-supported: A review of 551 children’s educational websites showed that approximately 60% have ads or unclear policies around advertising, including policies on behavioral and contextual advertising.1 For food companies, this offers an unparalleled opportunity to access children online and to market unhealthy foods.

CHILD-DIRECTED FOOD MARKETING

Child-directed food marketing is common and encourages unhealthy eating. Foods promoted to children are overwhelmingly of poor nutritional quality and high in added sugar, saturated fat, and sodium.2 Research from several groups3 robustly demonstrates that exposure to food marketing leads children to overconsume snack foods in the short term and can have lasting impacts by shaping children’s preferences, requests, and intake toward brands they have seen advertised.4 In the U.S., children’s dietary quality decreases considerably from preschool through adolescence,5 and 1 in 3 children have overweight or obesity.6 Weight outcomes are the poorest for Black and Latinx children,6 groups that are also disproportionately targeted by food companies with their marketing. WHO and other prominent health organizations call for limits on child-directed food marketing because it contributes to diets of poor nutritional quality and excess weight gain, with particular concerns about digital food marketing.7 Children do not comprehend the persuasive intent of advertising,8 and such persuasion is especially pronounced in the online arena.9 Digital marketing uses multiple data sources and applies machine learning to make advertised products particularly compelling.7 Even the seemingly basic contextual advertising, which was once solely reliant on matching ad placement to website content, today utilizes a number of multifaceted techniques designed to make ads appealing to children.7

The use of online material within the school curriculum is common, highlighting the potential for student exposure to digital marketing: During the 2016−2017 school year, 92% of middle school teachers assigned work that required students to go online during school and 64% assigned online homework.10 Spending on traditional school-based marketing dropped between 2006 and 2009, whereas spending on digital marketing both on and off school grounds increased by >50% in that time.11 Food marketing within websites promoting themselves as educational is also common: In 2016, among kids’ websites with the most banner ads for food and beverages from companies participating in the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI), an industry self-regulatory program for child-directed food marketing, 3 of 10 were educational websites (PopTropica.com, ABCya.com, FunBrain.com).2 Educational websites also ranked in the top 10 for snack, sugary drink, fast food, and sugary cereal ads as documented in multiple independent reviews of food marketing in children’s websites completed in 2012−2015.12

Food marketing within the context of learning is particularly concerning. Peripheral food cues in digital media effectively capture children’s attention,13 and cues within digital educational platforms can thus distract from learning. Food marketing that is integrated into games on educational websites, such as in-stream video ads within gaming platforms, may also enhance the effectiveness of food marketing because young children do not distinguish it from content.14 Child-directed food marketing within sites promoted by schools also undermines schools’ educational and health promotion efforts by suggesting that the school supports such marketing practices.

Many commercial educational websites had an established presence for supplementing learning before the coronavirus outbreak and thus are well positioned for use during remote learning. The ABCya! website includes testimonials from teachers who have used the platform in their classroom, and Common Sense Media includes example lesson plans from teachers who have used the ABCya! platform.15 Commercial educational websites have also been promoted specifically for use during remote learning. For example, the California State Parent Teacher Association website recommends FunBrain and ABCya! for remote learning.16 The authors have also heard from many parents concerned about food marketing on commercial educational websites that were suggested by their children’s teachers during remote learning.

Many popular educational websites promote themselves as appropriate for the classroom and to supplement learning, for example, by aligning with Common Core standards. Many of the games on the sites are engaging, and teachers should have the option to recommend their use to students. However, unhealthy food marketing within sites intended to supplement learning may undermine schools’ health promotion efforts by suggesting that the school supports the food and beverages being marketed. Although it is possible to view ad-free content by installing ad-blocking software or by or purchasing a paid subscription on some popular educational websites (e.g., ABCya.com, coolmathgames.com), subscription costs can be prohibitive for many families struggling financially. The burden to ensure an ad-free experience when engaging in digital material promoted by the company as supplementing learning should not fall on schools and parents.

ILLUSTRATIVE EXAMPLE: ABCYA.COM

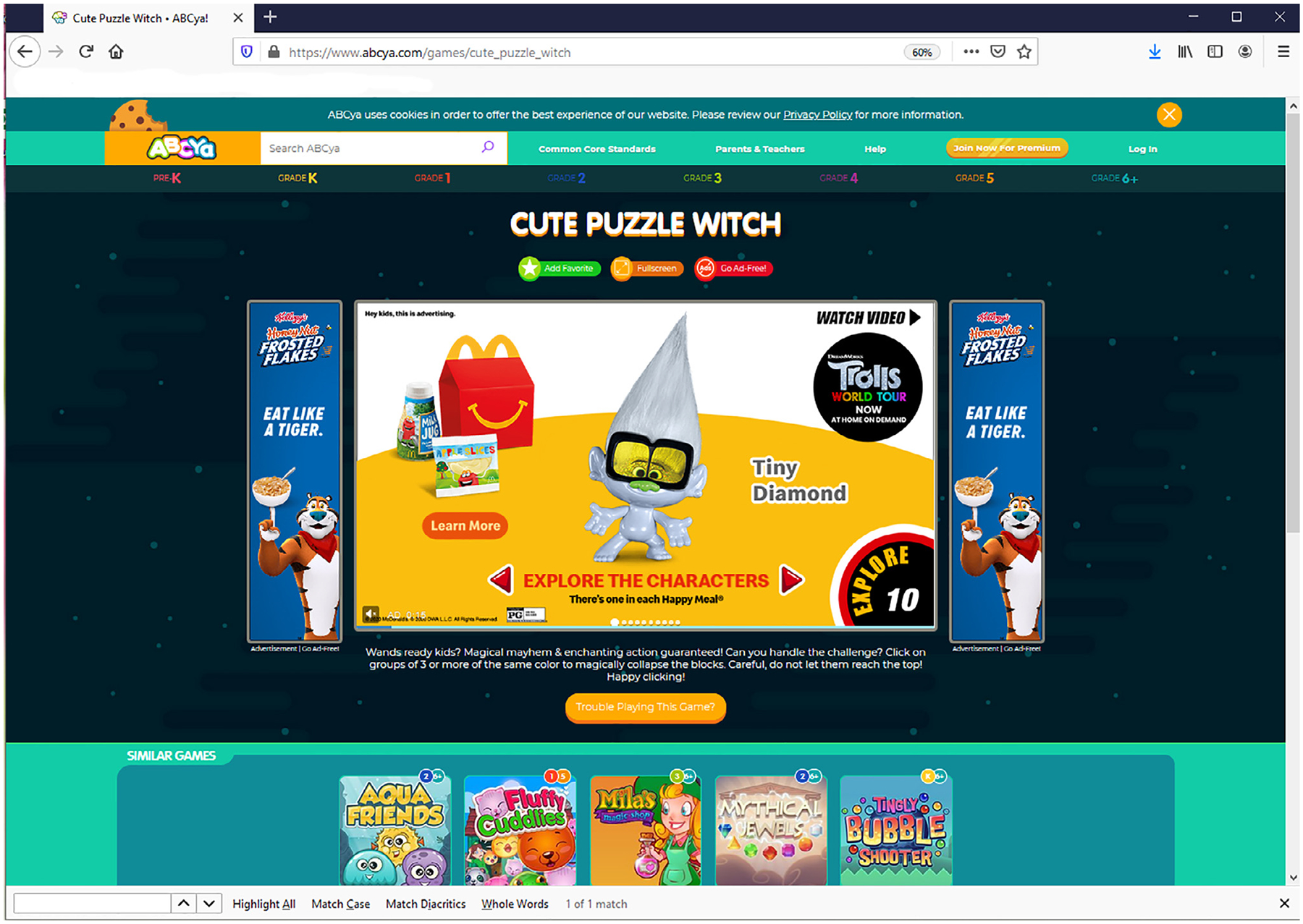

The authors visited several commercial educational websites during March−July 2020 to scan for the presence of food marketing after hearing from many parents about such marketing, as well as after one author’s own experience using these websites for remote learning. They observed marketing for sugary cereals, fast food, and packaged kids’ meals on ABCya.com, FunBrain.com, and PopTropica.com. Here, the authors present one example involving ABCya!, selected because of the website’s popularity and focus on elementary school children. ABCya! (ABCya.com) offers >400 educational games and applications for children in pre-kindergarten to Grade 5 and claims that “millions of users each month” engage with their products. ABCya! also promotes >240 games aligned with the Common Core and Next Generation Science standardized learning criteria. The group browsed several games on ABCya! under the second grade landing page by randomly clicking on games that appeared on that page and then on subsequent pages. They did not systematically audit all games, but instead scanned the platform to assess a user’s potential exposure to food ads while browsing the site. Food ads were prominently displayed at the start of many games. For example, from May 20, 2020 to June 5, 2020, screenshots of food ads were collected within 23 unique games that were randomly selected; samples were collected at various times during the day, from 4:30am until 8:00pm. Observed ads were for Kellogg’s Honey Nut Frosted Flakes (in 16 games), McDonald’s Happy Meals (in 7 games), and Kraft Heinz Lunchables Chicken Popper Kabobbles (in 4 games). The authors also observed ads for milk sponsored by America’s Milk Companies (in 3 games). They did not observe ads for other food or beverage brands in this sample. Ads included displays at the side of (e.g., skyscraper ads) and below the main game window and in-stream ads that are short video clips played before the game can start (Figure 1). Ads on ABCya.com were placed by Google Ads, the leading digital marketing service that has an unprecedented capacity to target ads based on contextual, demographic, and behavioral methods. In one instance, authors observed different ads on the same ABCya! online educational game depending on whether an elementary school−aged child or adult accessed the game from their respective personal devices; both accessed the same online game at the same time and were exposed to sugary cereal or computer software ads, respectively. The group acknowledges that this illustrative example does not completely summarize the amount and type of food advertising a child may be exposed to on ABCya! in 2020. However, this experience of frequently viewing food ads on ABCya! aligns with a recent systematic report in which ABCya! ranked third among the 10 kids’ websites with the most banner ads for child-directed food and beverage brands in 2016.2

Figure 1.

Example food advertisements on one ABCya! online educational game, Cute Puzzle Witch.

Note: A display ad for Frosted Flakes is on each side of the gaming window, and an in-stream ad for McDonald’s Happy Meals was played in the gaming window before the game started. This screenshot was taken on May 22, 2020. The user’s bookmarks on the browser toolbar were blurred with a photo-editing software.

The Center for Science in the Public Interest, with support from this group, sent e-mails to the 3 food companies (Kellogg’s, Kraft Heinz, and McDonald’s) in late May 2020, requesting that their food ads be removed from ABCya!; each company responded within 1 week and pledged to remove the ads. McDonald’s further pledged to remove digital advertising on websites similar to ABCya.com for upcoming Happy Meal campaigns, and Kraft Heinz pledged to remove their current ads from similar sites and refrain from advertising on such sites for the remainder of 2020. An e-mail was also sent to CFBAI. They too acknowledged the concerns outlined by Center for Science in the Public Interest and stated that all initiative participants would stop advertising on ABCya! and similar websites for the remainder of 2020. These are notable steps for these companies and CFBAI, and the authors applaud them for recognizing the problematic nature of this marketing during this public health crisis. The group urges CFBAI and participants to incorporate these changes into the company pledges permanently.

A CALL TO ACTION

Further action is needed. Child-directed food marketing in the U.S. is self-regulated through CFBAI. Currently, 19 food, beverage, and restaurant companies have joined CFBAI and vowed to only market food and beverages to children aged <12 years that meet CFBAI-defined nutritional criteria. Pledges cover traditional and digital media but allow for many exceptions. The food ads observed on ABCya! were from CFBAI companies, and items met CFBAI’s self-created nutrition criteria. CFBAI members have also specifically pledged not to market any food, even those that meet CFBAI nutritional criteria, in elementary schools up to Grade 6.17 Yet, the current CFBAI policy is insufficient because it does not apply to curriculum materials, which include online resources. Absent stronger federal regulations, the authors urge food companies to immediately stop marketing unhealthy food in children’s educational digital platforms and to update their CFBAI pledges to cover curriculum material. They also urge educational platforms to prohibit food marketing, as this would prevent food and beverage marketing by companies not participating in CFBAI. These actions would align with the industry’s self-stated pledges to not market in elementary schools.

However, voluntary action from food companies is not enough for sustained and comprehensive change. Industry regulations alone are insufficient given that compliance and effectiveness are both lacking with voluntary industry pledges.18 Specifically, there are extensive, persistent limitations when it comes to CFBAI pledges on child-directed food marketing, including an insufficient definition for child-directed material19 and subpar nutritional criteria for healthy foods allowed to be marketed to children. For example, many products that meet CFBAI nutrition criteria and can be featured in child-directed marketing do not align with a healthy dietary pattern per the U.S. Dietary Guidelines for Americans.2

Federal regulations for child-directed food marketing on digital educational platforms and effective federal monitoring are needed, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is one body that can act. The USDA requires all school districts that participate in the national school meal programs to adopt policies on food marketing that apply to school campuses, defined as “all areas of the property under the jurisdiction of the school that are accessible to students during the school day.”20 Those policies should be expanded to include all remote learning and digital resources that serve as curriculum material, as well as digital material that purports to align with standardized educational criteria. The USDA should also issue guidance to schools about how school districts can prevent children’s online marketing exposure when students use school-issued and personal devices. In the longer term, Congressional action could prevent any child-directed food marketing for unhealthy food and beverages within any digital media, as well as traditional media and in-store marketing, with criteria defined by a group independent of industry. As stated by WHO, regulations on child-directed food marketing in digital media are a “recognition of governments’ duty to protect the rights of children online, including their right to health.”7

CONCLUSIONS

Promoting unhealthy food on educational websites undermines the intended learning experience and does not support the development of healthy eating habits among children and thus fails to support educators and parents. The authors, a diverse group of researchers and advocates for child health, call on the food, beverage, and restaurant industries to support parents’ efforts to raise healthy children and teachers’ efforts to educate children by committing to no food marketing on any educational platform as part of their self-regulatory pledges. Recognizing the limits of self-regulation, the group calls for the USDA to strengthen Local Wellness Policy regulations on food marketing to limit students’ exposure through digital educational material. Industries must permanently revise their pledges with the CFBAI to stop food marketing within digital educational platforms and curriculum material, and online educational platforms that purport to supplement standardized learning criteria should adopt strong, public-facing children’s marketing policies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The statements presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of any author affiliations.

JAE was supported by NIH, Grant Number K01DK117971. FFM was supported by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Princeton, New Jersey. The views expressed here do not necessarily reflect the views of NIH or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

All authors made a substantial contribution to conception of the work and writing or revising of the article for important intel-lectual content and read and approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reviews. Common sense education. https://www.commonsense.org/education/search?contentType=reviews. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- 2.Harris JL, Frazier W, Romo-Palafox M, et al. Food industry self-regulation after 10 years: progress and opportunities to improve food advertising to children. Hartford, CT: The UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity; 2017. http://www.uconnruddcenter.org/files/Pdfs/FACTS-2017_Final.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith R, Kelly B, Yeatman H, Boyland E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: a systematic critical review. Nutrients. 2019;11(4):875. 10.3390/nu11040875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emond JA, Longacre MR, Drake KM, et al. Exposure to child-directed TV advertising and preschoolers’ intake of advertised cereals. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2):e35–e43. 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson JL, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Goodman MH, Landry AS. Diet quality in a nationally representative sample of American children by sociodemographic characteristics. Am J Clin Nutr. 2019;109(1):127–138. 10.1093/ajcn/nqy284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of obesity and severe obesity in U.S. children, 1999–2016 [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2018;142(3):e20181916]. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3):e20173459. 10.1542/peds.2017-3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Tackling food marketing to children in a digital world: trans-disciplinary perspectives: children’s rights, evidence of impact, methodological challenges, regulatory options and policy implications for the WHO European Region. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2016. https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/322226/Tackling-food-marketing-children-digital-world-trans-disciplinary-perspectives-en.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graff S, Kunkel D, Mermin SE. Government can regulate food advertising to children because cognitive research shows that it is inherently misleading. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(2):392–398. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Digital Democracy. The new age of food marketing: how companies are targeting and luring our kids − and what advocates can do about it. Washington, DC: Center for Digital Democracy; 2011. https://www.democraticmedia.org/content/new-age-food-marketing. Published 2011. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Polacsek M, Boninger F, Molnar A, O’Brien LM. Digital food and beverage marketing environments in a national sample of middle schools: implications for policy and practice. J Sch Health. 2019;89(9):739–751. 10.1111/josh.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Federal Trade Commission. A review of food marketing to children and adolescents. Washington, DC: U.S. Federal Trade Commission; 2012. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/review-food-marketing-children-and-adolescents-follow-report/121221foodmarketing-report.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 12.FACTS reports. UConn Rudd Center for Food Policy & Obesity. http://uconnruddcenter.org/facts-reports. Accessed October 23, 2020.

- 13.Folkvord F, Anschütz DJ, Wiers RW, Buijzen M. The role of attentional bias in the effect of food advertising on actual food intake among children. Appetite. 2015;84:251–258. 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buijzen M, Van Reijmersdal EA, Owen LH. Introducing the PCMC model: an investigative framework for young people’s processing of commercialized media content. Commun Theor. 2010;20(4):427–450. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2010.01370.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lesson plans for ABCya! Common Sense Education. https://www.commonsense.org/website/abcya/lesson-plans. Accessed August 18, 2020.

- 16.COVID-19 resources for parents, families and educators. California State: PTA. https://capta.org/news-publications/covid-19/covid-19-resources-for-parents-and-families/. Accessed July 31, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Companies agree to strengthen their children’s advertising commitments with CFBAI’s updated core principles. BBB National Programs. May 6, 2020. https://www.bbbprograms.org/media-center/blog-details/insights/2020/05/06/companies-agree-to-strengthen-their-children-s-advertising-commitments-with-cfbai-s-updated-core-principles. Accessed October 23, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taillie LS, Busey E, Stoltze FM, Dillman Carpentier FR. Governmental policies to reduce unhealthy food marketing to children. Nutr Rev. 2019;77(11):787–816. 10.1093/nutrit/nuz021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris JL, Sarda V, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Redefining “child-directed advertising” to reduce unhealthy television food advertising. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(4):358–364. 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Local school wellness policy. Food and Nutrition Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture https://www.fns.usda.gov/tn/local-school-wellness-policy. Accessed October 23, 2020.