Abstract

Background:

A systemic review was conducted to better understand the relationship between indoor tanning and body mass index (BMI), physical activity, or dietary practices.

Methods:

Articles included in this review were obtained via a systematic search of PubMed following PRISMA guidelines. Available articles were published between September, 2003 and May, 2017 and contained data regarding indoor tanning and BMI, physical activity, or dietary practices. Sixteen publications met final inclusion criteria.

Results:

Results of this review indicate significant positive associations between indoor tanning and high physical activity levels, playing sports, and both unhealthy and healthy diet and weight control practices. Frequent or dependent indoor tanning was associated with unhealthy dietary practices in most studies or risk for exercise addiction in one study. Results were mixed for BMI.

Conclusions:

This review demonstrates associations between indoor tanning and physical activity or dietary practices. Despite the use of some unhealthy strategies (e.g., indoor tanning, fasting, vomiting, laxative, or steroid use), common motives for these behaviors include a desire to appear attractive and/or healthy. Findings from this study can help inform future research and possible interventions for individuals engaging in relevant risky health behaviors.

Keywords: indoor tanning, physical activity, weight, BMI, diet, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

Despite its clear causal relationship with melanoma and other skin cancers, indoor tanning has been popular in recent decades, particularly among young white women and girls. From 2009-2015, the proportion of high school students under 18 who indoor tanned in the last 12 months was 26.8% for non-Hispanic white females, 2.3-7.9% for non-White females, 4.9% for non-Hispanic white males, and 4.3-4.9% for non-White males [1]. Indoor tanners cite several reasons for their participation in this risky behavior. However, the primary motivation is the desire to look attractive and appear healthy to their peers [2]. Other reasons include the desire to develop a “protective base tan” prior to prolonged sun exposure, self-treatment of various skin conditions such as acne, and a desire to increase vitamin D levels [3]. In addition, indoor tanners cite a feeling of relaxation and a sense of physical and mental well-being after tanning [4]. Furthermore, studies have shown that tanning dependence or addiction is possible, which is thought to be related to ultraviolet radiation exposure causing the release of endogenous opioids in the skin [3].

Most of these motives are not exclusive to indoor tanning. There are corresponding motivations and behaviors seen in individuals who diet and exercise as well. In addition to wanting to be healthy, these individuals also often want to look good and gain an increased sense of well-being [2, 5]. However, some unhealthy dietary behaviors may be reinforced by the short-term rewards of stress management and increased perceived attractiveness or positive reactions from others, often with minimal attention to the possible negative long-term health effects such as the development of full-blown eating disorders [4, 6]. In addition to the aforementioned motives, people use exercise to look and feel in shape, lose weight, be with friends and have fun, and relax or cope with stress [5].

Similar to tanning dependence is the phenomenon of the “runners high”, a feeling of euphoria after physical activity also due to the release of endogenous opioids [5]. People that experience this may be more likely to adopt excessive exercise patterns, becoming addicted to (or dependent upon) exercise. Like tanning dependence, exercise addiction is characterized by its having a negative impact on other life areas and/or feelings of deprivation when one is not able to engage in physical activity [7]. Those with confirmed exercise addiction, which is estimated at 3% of the exercising population, are also more likely to have excessive concerns about their body image, weight, and diet [5]. However, it is important to note that exercise is typically a healthy behavior; whereas, tanning is not, regardless of whether one is tanning dependent.

Despite the apparent similarities of these variables in terms of motives, the literature on indoor tanning as it relates to weight/body mass index (BMI), physical activity, or dietary practices has not been adequately summarized. A prior paper reviewed associations between skin cancer risk and protective behaviors and other health behaviors; however, the focus on indoor tanning was limited [8]. In the current paper, the literature on indoor tanning and these other health-related variables were systematically reviewed. We aimed to investigate the research available in order to better understand the similarities and differences as well as potential motivations and psychological mechanisms between indoor tanning and BMI, physical activity, or dietary practices in an effort to inform future research and behavior-change interventions. Based upon some apparent common motivations for these behaviors such as appearance-enhancement, we hypothesized that individuals who indoor tanned would be more likely to have 1) lower BMIs, 2) higher physical activity levels, and 3) a greater likelihood of dieting behaviors.

METHODS

Literature Search

Methods for this review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The primary database used for literature searches was MEDLINE (PubMed). The search identified publications between September 2003 (the date of the earliest publication meeting the other criteria) and May 2017. The title-abstract searches included “indoor tanning”, “tanning bed*”, OR “sunbed”, AND “body mass index”, “BMI”, “weight”, “obesity”, “physical activity”, “exercise”, “fitness”, “athletic*”, “sport*”, “diet”, “dieting”, “dietary”, “nutrition”, “eating disorder*”, bulimi*, anorex*, OR binge-eating.

Publication Selection and Exclusion

Papers included in this review addressed indoor tanning as well as BMI, physical activity, or dietary practices. Studies were initially excluded based upon titles irrelevant to our study purpose (e.g., publications focusing on Vitamin D synthesis). Publications deemed relevant based upon title were screened by their abstracts and vetted for inclusion in the review. Studies that did not specifically mention indoor tanning, but only sun exposure, outdoor sunbathing, or sunburn were discarded. Furthermore, any publication that focused only on psychological constructs such as body image or appearance-related issues rather than more objective or behavioral constructs such as weight, BMI, physical activity, or dietary habits was also discarded since the association between indoor tanning and body image or appearance concerns is well-known.

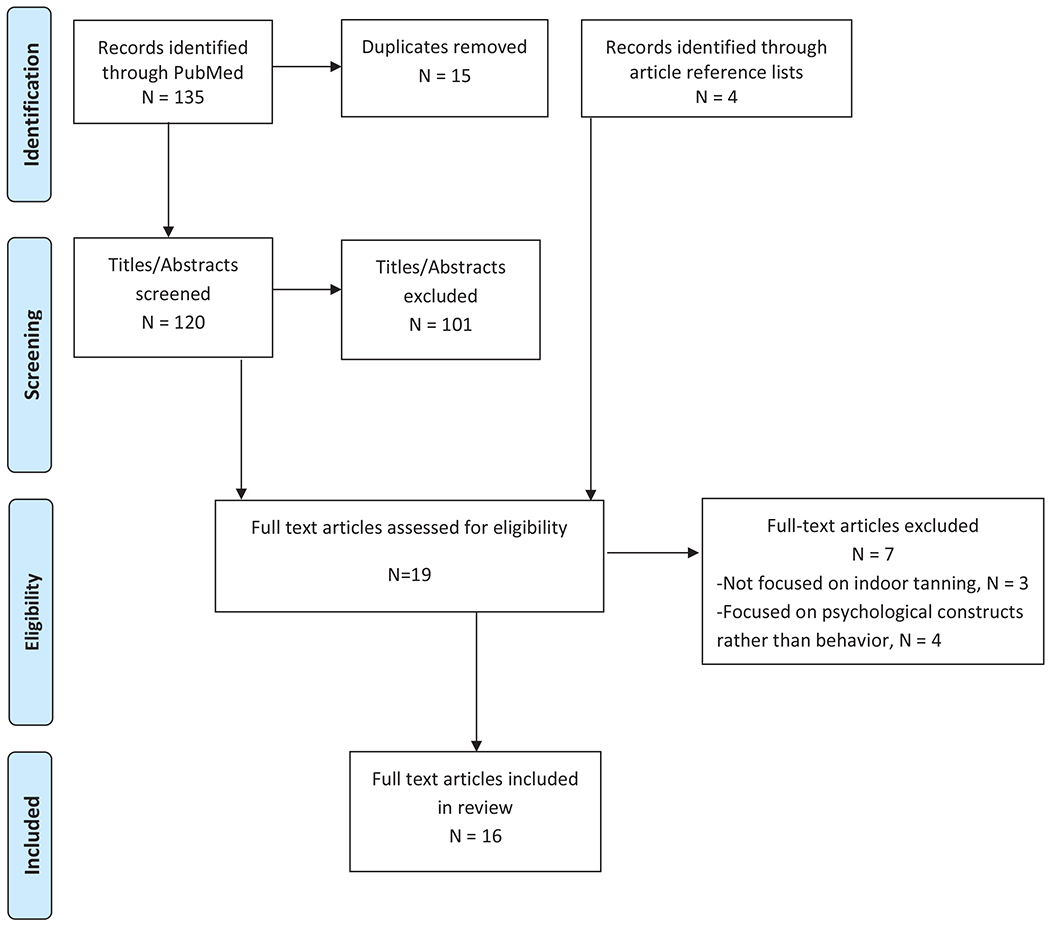

Abstracts that met inclusion criteria were selected for full-text review. An initial list of publications was compiled after all search combinations were exhausted. Full-text papers were reviewed for study inclusion, and, if appropriate, were added to the final list of publications. References from these studies were also scanned for inclusion, and if appropriate, included in the final publication list. Reviews were then removed in order to focus on original empirical data. The study selection and exclusion process is outlined in Figure 1. Odds ratios were calculated and converted to Cohen’s ds when possible [9], and the size and direction of statistically significant associations were noted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), or large (d = 0.8) [10].The final included studies were narratively reviewed, and threats to generalizability were noted when applicable.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Chart

RESULTS

Overview

A title-abstract search of PubMed yielded 135 initial publications, and after duplicates were removed, 120 titles/abstracts were screened for inclusion. Nineteen articles met inclusion criteria based on title-abstract relevance, and the references of these articles were screened for additional relevant papers. Four additional citations were identified for review, with no new references identified from their bibliographies. Thus, a total of 23 full-text publications were screened for eligibility. Seven articles were excluded after reading the full text for discussion of topics that did not address the goals of this review. For example, four articles only addressed the motives to indoor tan being appearance-based and made no reference to actual weight/BMI, physical activity, or dietary practices. Other papers addressed indoor tanning but related it to facial aging, tanning-related content in major magazines, or prevalence of tanning beds among fitness centers.

Of the final sixteen publications included in the review (see Table 1), nine were based on data analyzed from nationally-distributed surveys in the U.S., and four included locally- or regionally-collected data also from U.S. populations. Three studies examined populations that were outside of the U.S., including Denmark, Germany, and Canada. Publications were grouped into three categories for review: two papers exclusively addressed BMI; one exclusively addressed physical activity behaviors, and three addressed only weight control or dieting practices. Ten studies reported data that were applicable to more than one topic. Thus, ten BMI-related papers, ten physical activity papers, and eleven diet papers were included in the review. All of these studies collected data using cross-sectional self-report surveys, and most included adolescent or young adult samples only. Most studies focused on having ever indoor tanned in the past year, but some focused on a lifetime history of indoor tanning. A few studies addressed tanning frequency, and two focused on tanning dependence. The comparison groups and statistics reported for each group of studies were varied and, thus, did not allow for summary meta-analyses.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the systematic review

| Authors, Year | Paper Title | Questionnaire | Sample Size and Characteristics | Indoor Tanning Timeframe | Comparison Groups | Statistically Significant Associations (demographic findings bolded) | Strength and Direction of Associations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI | |||||||

| Cartmel et al., 2017 [17] | Predictors of tanning dependence in white non-Hispanic females and males | Yale Study of Skin Health in Young People Survey | 499 non-Hispanic white indoor tanners (75% female) from a case control study of early-onset (under age 40) basal cell carcinoma in Connecticut, US | History of tanning dependence (≥ 2 affirmative responses on the mCAGE scale and ≥ 3 affirmative responses on the mDSM-IV-TR scale) vs. not (not meeting criteria on both scales). | < 25 (Normal weight), 25 to < 30 (overweight), and ≥ 30 (obese)BMI | No significant difference in tanning dependence | NS |

| Choi et al., 2010 [12] | Prevalence and characteristics of indoor tanning use among men and women in the U.S. | 2005 National Cancer Institute Health Information National Trends Study | 2,869 US Caucasians aged 18-64 years | Past year | Non-overweight (24.9 and below), overweight (25.0 to 29.9), and obese (30.0 and above) BMI | Obesity was associated with a lower likelihood (AOR 0.30, d −0.67) of indoor tanning compared to not being overweight among men only. | Medium Negative |

| Coups et al., 2008 [11] | Multiple Skin Cancer Risk Behaviors in the U.S. Population | 2005 National Health Interview Survey | 28,235 US participants aged 18-65+ years | Lifetime | Normal (<25), overweight (25 to < 30), and obese BMI (≥ 30) | Overweight (OR 1.19-1.30, d 0.14 for ages 30+) or obesity (OR 1.18, d 0.09 for ages 40-49 and 1.49, d 0.22 for 65+) was associated with a higher likelihood of engaging in multiple skin cancer risk behaviors including indoor tanning. | Small Positive |

| Demko et al., 2003 [14] | Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the U.S. | 1996 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | 6,903 US non-Hispanic whites aged 13-19 years | ≥ 3 times in lifetime | > 85th percentile (Overweight) vs. ≤ 85th percentile (non-overweight) BMI | Higher BMI was associated with a lower likelihood (AOR 0.68, d −0.21) of indoor tanning. | Small Negative |

| Harland et al., 2016 [18] | Health behaviours associated with indoor tanning based on the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 2012/2013 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 64,174 7-12 grade students enrolled in 476 schools in Manitoba Canada, aged 12-18+ years | Lifetime | Healthy weight/underweight (equal to or less than the 85th percentile) vs. overweight/obese (greater than the 85th percentile) BMI | No significant difference | NS |

| Heckman, et al., 2008 [19] | Prevalence and Correlates of Indoor Tanning among U.S. Adults | 2005 National Health Interview Survey | 29,394 US participants aged 18-65+ years | Past year | Not overweight/obese (<25), overweight (25 to < 30), or obese BMI (≥ 30) | No significant difference | NS |

| Heckman, et al., 2008 [15] | A preliminary investigation of the predictors of tanning dependence. | Several prior surveys | 400 college-aged individuals | History of tanning dependence (≥ 2 affirmative responses on the mCAGE scale or ≥ 3 affirmative responses on the mDSM-IV-TR scale) vs. not (not meeting criteria on either scale). | Low to normal weight (<25), overweight (25 to < 30), or obese BMI (≥ 30) | Obese individuals were less likely (OR 0.34, d - 0.6) to be tanning dependent than low to normal weight individuals. | Medium Negative |

| Meyer et al., 2017 [13] | Sunbed use among 64,000 Danish students and the associations with demographic factors, health-related behaviours, and appearance-related factors | 2014 Danish National Youth Study Survey | 64,382 Danish students aged 15-25 years enrolled in upper secondary schools, higher preparatory examination schools, and vocational colleges | Past year | Underweight (Less than the 5th percentile), normal weight (5th percentile to less than the 85th percentile), and overweight BMI (greater than the 85th percentile) | Being underweight was associated with a lower likelihood (AOR 0.8, d −0.12 for females, AOR 0.5, d −0.38 for males) of having indoor tanned. Overweight was associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.5, d 0.22) of having indoor tanned among male students only. | Small Positive |

| O’Riordan et al., 2006 [20] | Frequent tanning bed use, weight concerns, and other health risk behaviors in adolescent females | 1996 Growing up Today Study Survey | 6,373 US adolescent females aged 9-14 (primarily middle-class, >90% white) whose mothers participated in the Nurse’s Health Study II | Past year | Lean <15%, moderate (15-84%), and overweight (≥85%) BMI. | No significant difference | NS |

| Yoo et al., 2012 [16] | Adolescents’ body-tanning behaviours: Influences of gender, body mass index, sociocultural attitudes towards appearance and body satisfaction | Questionnaire developed for the study | 357 students enrolled in 7 high schools in Texas, US aged 11-14 years (>92% Caucasian) | Lifetime | Underweight (<18.5), normal weight (18.5-24.99), and overweight (≥25) BMI | Normal weight was associated with a lower likelihood (beta −0.54, OR 0.58, d −0.30) of having indoor tanned compared to being overweight. | Small Positive |

| Physical Activity | |||||||

| Cartmel et al., 2017 [17] | Predictors of tanning dependence in white non-Hispanic females and males | Yale Study of Skin Health in Young People Survey | 548 non-Hispanic whites (75% female) from a case control study of early-onset (under age 40) basal cell carcinoma in Connecticut, UA | History of tanning dependence (≥ 2 affirmative responses on the mCAGE scale and ≥ 3 affirmative responses on the mDSM-IV-TR scale) vs. not (not meeting criteria on both scales). | At risk for exercise addiction (a score of ≥ 24 on the six-item exercise addiction inventory) vs. not | Being at risk for exercise addiction was significantly associated with a higher likelihood of being tanning dependent (OR 5.47, d 0.94). | Large Positive |

| Choi et al., 2010 [12] | Prevalence and characteristics of indoor tanning use among men and women in the U.S. | 2005 National Cancer Institute Health Information National Trends Study | 2,869 US Caucasians aged 18-64 years | Past year | Moderately exercising ≥ 150 minutes per week vs. not. | No significant difference | NS |

| Demko et al., 2003 [14] | Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the U.S. | 1996 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | 6,903 US non-Hispanic whites aged 13-19 years | ≥ 3 times in lifetime | Weekly frequency of a variety of active sports or exercises per week | Higher frequency of physical activity was associated with a lower likelihood (AOR 0.91, d −0.05) of indoor tanning among girls only. | Very Small Negative |

| Diehl et al., 2010 [23] | The prevalence of current sunbed use and user characteristics: the SUN-Study 2008 | 2008 Sunbed-Use: Needs for Action Study | 500 randomly selected adults aged 18-45 years from Mannheim in Southwest Germany | Past year | Individual sports (e.g., aerobics or strengths training) vs. team sports, martial arts, or no sports | Participating in individual sports was associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.8, d 0.32) of indoor tanning. | Small Categorical |

| Guy et al., 2014 [22] | Indoor tanning among high school students in the U.S., 2009 and 2011 | 2009 and 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 25,861 US high school students aged 14-18 years | Past year | Played on at least one sports team run by their school or community group in the past year | Playing on at least one sports team was associated with a higher likelihood (27.1 vs. 19.8% for females and 5.7 vs. 4.2% for males) of indoor tanning. | Positive |

| Harland et al., 2016 [18] | Health behaviours associated with indoor tanning based on the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 2012/2013 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 64,174 7-12 grade students enrolled in 476 schools in Manitoba Canada, aged 12-18+ years | Lifetime | Inactive, moderately active, and active based on number of minutes in the past week of reported vigorous or moderate activity | Moderate activity or inactivity was associated with a lower likelihood (OR 0.80, d −0.12 for females, OR 0.72, d −0.18 for males) of having indoor tanned compared to higher physical activity. | Small Positive |

| Heckman, et al., 2008 [19] | Prevalence and Correlates of Indoor Tanning among U.S. Adults | 2005 National Health Interview Survey | 29,394 US participants aged 18-65+ years | Past year | None, some (1-674 metabolic equivalents [METS), meets recommendations (≥ 675 METS) | No significant difference | NS |

| Heckman, et al., 2008 [15] | A preliminary investigation of the predictors of tanning dependence. | Several prior surveys | 400 college-aged individuals | History of tanning dependence (≥ 2 affirmative responses on the mCAGE scale or ≥ 3 affirmative responses on the mDSM-IV-TR scale) vs. not (not meeting criteria on either scale). | Low, moderate, or high anaerobic or aerobic exercise | No significant difference | NS |

| Meyer et al., 2017 [13] | Sunbed use among 64,000 Danish students and the associations with demographic factors, health-related behaviours, and appearance-related factors | 2014 Danish National Youth Study Survey | 64,382 Danish students aged 15-25 years enrolled in upper secondary schools, higher preparatory examination schools, and vocational colleges | Past year | Duration of time spent outside of school exercising to the extent that students became breathless or sweaty compared to ≥ 7 hours per week | Shorter duration of exercise was associated with lower likelihood (AOR 0.4-0.8, d −0.12 - −0.51 for females, AOR 0.3-0.6, d −0.28 - −0.67 for males) of indoor tanning. | Small to Medium Positive |

| Miyamoto et al., 2012 [21] | Indoor tanning device use among male high school students in the U.S. | 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 7,219 US male students in grades 9-12 | Past year | Played on at least one sports team run by their school or community group in the past year | Playing on at least one sports team was associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.7, d 0.29) of indoor tanning. | Small Positive |

| Dietary Practices | |||||||

| Amrock & Weitzman, 2014 [25] | Adolescent indoor tanning use and unhealthy weight control behaviors | 2009 and 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 26,951 US high school students | Past year | Unhealthy dietary practices (took diet pills, powders, or liquids; vomited or took laxatives; or did not eat for ≥ 24 hours to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight during the past 30 days) vs. none. | Unhealthy dietary practices were associated with a higher likelihood (OR 1.23-2.37, d 0.11-0.48 for females, OR 2.29-7.07, d 0.46-1.08 for males) of having indoor tanned. | Small to Medium Positive Unhealthy for Females Medium to Large Positive Unhealthy for Males |

| Blashill et al., 2013 [24] | Psychosocial correlates of frequent indoor tanning among adolescent boys | 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 7,521 US male high school students | ≥ 10 times in past year | Unhealthy dietary practices (took diet pills, powders, or liquids; vomited or took laxatives; or did not eat for ≥ 24 hours to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight during the past 30 days) vs. none. History of non-prescription steroid use vs. none. Trying to lose weight vs. not or trying to gain weight vs. not. |

Frequent indoor tanning was associated with a higher likelihood of unhealthy dietary practices (OR 1.95-2.34, d 0.37-0.47), non-prescription steroids (OR 3.67, d 0.72), or attempting to gain weight (OR 1.51, d 0.24). | Small to Medium Positive Unhealthy |

| Choi et al., 2010 [12] | Prevalence and characteristics of indoor tanning use among men and women in the U.S. | 2005 National Cancer Institute Health Information National Trends Study | 2,869 US Caucasians aged 18-64 years | Past year | Attempting to lose weight in the past year vs. not. | No significant difference | NS |

| Demko et al., 2003 [14] | Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the U.S. | 1996 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health | 6,903 US non-Hispanic whites aged 13-19 years | ≥ 3 times in lifetime | Dieting to lose weight, gain weight, or not dieting | Dieting to lose weight was associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.26, d 0.13) of indoor tanning. | Small Positive Unhealthy |

| Gillen & Markey, 2017 [26] | Beauty and the burn: tanning and other appearance-altering attitude and behaviors | Questionnaire developed for the study | 284 undergraduate students aged 18-59 years from a public university in New Jersey, US | Lifetime | Scores on healthy (e.g., eat less fat) and unhealthy (e.g., fasting) dieting scales | Higher scores on healthy dietary practices were associated with a higher likelihood of having indoor tanned (F = 7.21). | Positive Healthy |

| Guy et al., 2014 [22] | Indoor tanning among high school students in the U.S., 2009 and 2011 | 2009 and 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 25,861 US high school students aged 14-18 years | Past year ≥10 times (frequent) in past year | Eating fruits or vegetables ≥ 5 times a day in the past week vs. not. History of non-prescription steroid use vs. not. Unhealthy weight control practices (took diet pills, powders, or liquids; vomited or took laxatives; or did not eat for ≥ 24 hours to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight during the past 30 days) vs. none. |

Indoor tanning was associated with eating fruits or vegetables (6.3 vs. 4.8%), a history of non-prescription steroiduse (12 vs. 4.7%), or unhealthy weight control practices (9.3 vs. 4.5%) among male students.

Indoor tanning was associated with unhealthy weight control practices (27.8 vs. 22.7%) among female students. Frequent indoor tanning was associated with a history of non-prescription steroid use (65.5 vs. 52.5%) among female students. |

Positive Healthy and Unhealthy for Males. Positive Unhealthy for Females. |

| Harland et al., 2016 [18] | Health behaviours associated with indoor tanning basedon the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 2012/2013 Manitoba Youth Health Survey | 64,174 7-12 grade students enrolled in 476 schools in Manitoba Canada, aged 12-18+ years | Lifetime | Consumption of fruits and vegetables ≥ 4 times, soft drink or diet soft drink, creatine or other supplements, meal replacement bars or shakes, fast food yesterday vs. not |

Lower fruit and vegetable consumption was associated with a lower likelihood (OR 0.76, d −0.15) of having indoor tanned among male students.

Engagement in any of the other dietary behaviors was associated with a higher likelihood of having indoor tanned among females (OR 1.14-2.08, d 0.07-0.40) and males (OR 1.44-3.55, d 0.20-0.70). |

Small Positive Healthy Small to Medium Positive Unhealthy |

| Heckman, et al., 2008 [19] | Prevalence and Correlates of Indoor Tanning among U.S. Adults | 2005 National Health Interview Survey | 29,394 US participants aged 18-65+ years | Past year | ≥ 5 fruit/vegetable servings per day < 5 fruits/vegetable servings per day | 40-49 year olds who ate fewer fruits/vegetables were more likely (OR 1.29, d 0.14) to have indoor tanned. | Small Negative Healthy |

| Meyer et al., 2017 [13] | Sunbed use among 64,000 Danish students and the associations with demographic factors, health-related behaviours, and appearance-related factors | 2014 Danish National Youth Study Survey | 64,382 Danish students aged 15-25 years enrolled in upper secondary schools, higher preparatory examination schools, and vocational colleges | Past year | Scores on a healthy dietary habits (i.e., eating fruit, vegetables, or wholegrains daily) scale for the past week. Dieting to lose weight 1-4 times, ≥ 5 times, or not during the past year. |

Poor dietary habits (compared to excellent dietary habits) were associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.6, d 0.26) of indoor tanning among female students.

More frequent dieting to lose weight was associated with a greater likelihood (AOR 1.9-2.7 , d 0.35 – 0.55 for females, 1.6-1.8, d 0.26 – 0.32 for males) of having indoor tanned. |

Small to Medium Positive Unhealthy |

| Miyamoto et al., 2012 [21] | Indoor tanning device use among male high school students in the U.S. | 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey | 7,219 US male students in grades 9-12 | Past year | Eating fruits and vegetables ≥ 5 times a day in the past week vs. not. History of non-prescription steroid use vs. none. Unhealthy dietary practices (took diet pills, powders, or liquids; vomited or took laxatives; or did not eat for ≥ 24 hours to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight during the past 30 days) vs. none. |

Eating more fruits and vegetables was associated with a higher likelihood (AOR 1.6, d 0.26) of having indoor tanned. A history of non-prescription steroid use (AOR 4.0, d 0.77) or unhealthy dietary practices (AOR 2.5, d 0.51) was associated with a higher likelihood of having indoor tanned. |

Small Positive Healthy Medium Positive Unhealthy |

| O’Riordan et al., 2006 [20] | Frequent tanning bed use, weight concerns, and other health risk behaviors in adolescent females | 1996 Growing up Today Study Survey | 6,373 US females aged 9-14 (primarily middle-class, >90% white) whose mothers participated in the Nurse’s Health Study II | Infrequent/moderate (1-9 times), frequent (≥ 10 times), or no indoor tanning in the past year | At least monthly use of laxatives or vomiting to control weight in the past year vs. not. Dieting to lose or keep from gaining weight at least once per week in the past year vs. not. |

Use of laxatives or vomiting to control weight was associated with a higher likelihood of infrequent/moderate (AOR 1.9, d 0.35) or frequent (AOR 3.6, d 0.71) indoor tanning. Dieting was associated with a higher likelihood of frequent indoor tanning (AOR 1.5, d 0.22). |

Small to Medium Positive Unhealthy |

Note: OR = odds ratio, AOR = adjusted odds ratio, d = Cohen’s d, NS = non-significant

BMI

Contrary to our hypothesis that indoor tanning would be negatively associated BMI, , the findings were disparate. Indoor tanning was negatively associated with BMI in three studies with small to medium effects sizes, positively associated in three studies with small effect sizes, and there was no association in four studies. There were differences by age in terms of the association between BMI and indoor tanning within one study [11] and differences by sex with BMI being associated with indoor tanning, but in two different directions, for men only in two studies [12, 13].

Negative associations with indoor tanning.

With regard to negative associations between indoor tanning and BMI, one study was based on data from the 1996 National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (NLSAH) survey. Participants in Demko and colleagues’ study were adolescents aged 13-19 years across 132 schools in 80 communities nationwide. 6,903 non-Hispanic white participants were included in this study [14]. Participants were asked to estimate the number of times they visited an indoor tanning salon in their lifetime. Students with BMIs greater than 85th percentile were less likely to have indoor tanned three or more times compared to others [14]. Additionally, data from the 2005 National Cancer Institute’s Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) showed that men who were classified as obese were less likely to report indoor tanning in the last year compared to non-overweight me [12]. The 2,869 participants in this telephone-based study were Caucasians aged 18-65, which included a wider age range than most other publications reviewed here [12]. A final study focused on tanning dependence (which was associated with past year, warm weather, and lifetime indoor tanning) among college-aged individuals from the Southeastern US found that individuals who were classified as obese were less likely to be tanning dependent than people classified as non-obese [15].

Positive associations with indoor tanning.

In contrast, three studies found a positive association between BMI and indoor tanning. For example, a study performed on 357 public high school students in Texas found that students in the BMI group classified as overweight was more likely than the normal BMI group to report indoor tanning in their lifetimes [16]. A previous study by our group relying on national data from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) sampled 28,235 adults and found a greater number of skin cancer risk behaviors, including indoor tanning, in the past year, among those who were classified as overweight or obese compared to others [11]. In populations outside of the U.S., one study performed by Meyer and colleagues was based upon a questionnaire that surveyed 64,382 young people aged 15-25 in Denmark [13]. Students who were considered underweight according to their BMI were less likely to have visited an indoor tanning salon in the past year, and male students who were considered overweight were more likely to have indoor tanned [13].

No significant associations with indoor tanning.

The following studies found no significant association between BMI and indoor tanning. A study on tanning dependence and three BMI categories assessed 548 non-Hispanic men and women under the age of 40 in Connecticut who had participated in a case-control study of early onset basal cell carcinoma [17]. One study conducted from 2012-2013 in Manitoba, Canada surveyed 64,164 students in grades 7-12, who were enrolled in 476 schools in the area, and assessed lifetime indoor tanning and two BMI categories [18]. Another study by our group of 29,394 adults from the 2005 NHIS analyzed indoor tanning in the past year, rather than lifetime history as in a previously mentioned study, and three BMI categories [19]. The 1996 Growing Up Today (GUT) survey of 6,373 adolescent females was distributed to mothers who had participated in the Nurse’s Health Study II and indicated that they had a child aged 9-14 [20]. This study investigated past year indoor tanning and three categories of BMI [20].

Physical Activity

For the most part, our hypothesis about the positive association between indoor tanning and physical activity was supported.

Positive associations with indoor tanning.

Five studies found positive associations with varying effect sizes between indoor tanning and physical activity/participation in sports. Miyamoto and colleagues assessed data from 7,219 male participants in the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSSS) [21]. The authors found that high school students who had played on at least one sports team were significantly more likely to have indoor tanned in the past year [21]. A similar study used an expanded sample to include data from both the male and female students in the 2009 and 2011 YRBSS, providing a total sample of 25,861 participants [22]. Guy and colleagues found that playing on at least one sports team was associated with indoor tanning in the past year for both male and female participants [22]. There was also a trend (p = 0.06) toward playing on at least one sports team being associated with frequent 10 or more times) indoor tanning among female students [22].

Two studies focused on populations outside of the U.S. and reported similar relationships between sunbed use and physical activity. One study conducted from 2012-2013 in Manitoba, Canada surveyed 64,164 students in grades 7-12, who were enrolled in 476 schools in the area [18]. Having ever indoor tanned was significantly associated with greater physical activity in the past week [18]. Similarly, Meyer and colleagues assessed how many hours outside of school Danish students aged 15-25 years exercised to the extent that they became breathless or sweaty [13]. It was found that more hours of exercise was associated with more sunbed use in the past year [13].

One unique study assessed tanning dependence in 548 non-Hispanic women and men under the age of 40 in Connecticut who had participated in a case-control study of early onset basal cell carcinoma [17]. High scores on an exercise addiction scale were significantly associated with tanning dependence, which was associated with a higher number of lifetime indoor tanning sessions [17].

Significant association with individual sports only.

In another study conducted in Mannheim, Germany, investigators sampled 500 18-45 year-olds in the 2008 telephone-based Sunbed-Use: Needs for Action-Study (SUN-Study) [23]. Interestingly, it was determined that persons engaging in individual sports such as aerobics or strength training were more likely (small effect size) to have used a sunbed in the past year than a group characterized by doing team sports, martial arts, or who did not engage in sports [23].

No significant association with indoor tanning.

Three studies did not demonstrate a significant association between indoor tanning and physical activity. This includes the 2005 HINTS study that assessed indoor tanning in the past year and exercising moderately for at least 150 minutes per week among the 2,869 Caucasians aged 18-65 who participated in this telephone-based study [12]. The study of 29,394 adults from the 2005 NHIS analyzed indoor tanning in the past year and three categories of metabolic equivalents [19]. A tanning dependence study among college-aged individuals from the Southeastern US assessed low, moderate, and high aerobic and anaerobic exercise [15].

Negative association with indoor tanning.

Only one publication found a negative association between indoor tanning and sports or exercise. In 1996, Demko and colleagues determined that a higher level of physical activity per week was associated with a lower likelihood (small effect size) of having indoor tanned three or more times during their lifetime among female non-Hispanic white adolescents from the U.S [14]. This was the only study for which there were sex differences in the association with physical activity.

Dietary Practices

Consistent with our hypothesis, ten of the eleven publications included in this review found a significant association between indoor tanning and one or more dietary habits or weight control behaviors. Note that some of these studies had more than one outcome and mixed findings within the same study.

Positive associations with unhealthy dietary practices.

Seven publications including one or more relevant outcomes found positive associations of varying sizes between indoor tanning and unhealthy dietary behaviors used for the purpose of either losing weight or gaining muscle mass. The 1996 GUT survey of 6,373 adolescent girls was distributed to mothers who had participated in the Nurse’s Health Study II and indicated that they had a child aged 9-14 [20]. The GUT study found that use of laxatives and vomiting to control weight were associated with girls’ infrequent/moderate (1-9 times in the past year) or frequent (10 or more times) indoor tanning [20]. In the study by Meyer and colleagues, it was found that among young female (but not male) Danes, poorer dietary habits including eating fewer fruits, vegetables, or whole-grain products daily in the past week was associated with a higher likelihood of indoor tanning in the past year [13]. Additionally, Harland and colleagues found that drinking soft drinks or diet soft drinks, taking creatine or other supplements, using meal replacement bars or shakes, or eating fast food the prior day was significantly associated with greater lifetime indoor tanning among Canadian high school students [18].

Four studies used data from the 2009 and/or 2011 YRBSS. Two studies focused on 2009 data from more than 7,000 male high school students. Miyamoto and colleagues found that unhealthy dietary practices including use of diet pills, fasting, vomiting in the past 30 days, or a history of non-prescription steroid use were associated with indoor tanning in the past year [21], and Blashill found that these behaviors were associated with frequent ( 10 or more times in the past year) indoor tanning [24]. Similarly, Amrock and Weitzman used data from the 2009 and 2011 YRBSS and found that among both male and female students, those who indoor tanned in the past year had a higher likelihood of unhealthy weight control behaviors in the last thirty days [25]. Also using 2009 and 2011 YRBSS data, Guy and colleagues confirmed unhealthy dietary practices and non-prescription steroid use to be associated with indoor tanning in the past year among male high school students [22]. Unhealthy dietary practices were associated with indoor tanning, and non-prescription steroid use was associated with frequent indoor tanning in the past year among female high school students [22]. The findings by sex varied in terms of variables of interest and effect sizes.

Positive associations with attempting to lose or gain weight.

Four studies examined dietary practices that may or may not have been healthy depending on the baseline weight of participants and the specific dieting behaviors used. These studies found positive associations of varying sizes between weight management and indoor tanning. For example, among the sample of 6,903 non-Hispanic white adolescents in the 1996 NLSAH, “dieting to lose weight” was associated with having ever indoor tanned at least three times, when adjusted for other variables such as BMI [14]. The GUT survey also performed in 1996 showed that dieting to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight at least once per week in the past year was associated with frequent (10 or more times in the past year) indoor tanning among female adolescents, when adjusted for weight-related variables such as BMI [20]. Meyer and colleagues found that among young female Danes, more frequent dieting to lose weight was also associated with a higher likelihood of indoor tanning in the past year, when adjusted for variables such as BMI [13]. Finally, Blashill found that attempting to gain weight was associated with a higher likelihood of frequent indoor tanning, when adjusted for perceived weight status, among 7,521 male high school students who completed the 2009 YRBSS [24].

Negative association with healthy dietary practices.

In addition, one paper found a small negative association between indoor tanning and healthy dietary behaviors. The study of 29,394 adults from the 2005 NHIS found that indoor tanning in the past year was significantly associated with having eaten fewer daily servings of fruits or vegetables among 40-49 year olds only [19]. This was the only study of dietary practices that found differences by age.

Positive associations with healthy dietary practices.

Four publications found significant associations (small and unknown effects sizes) between indoor tanning and seemingly healthy dietary behaviors, primarily eating fruits or vegetables. For example, a study including 284 male and female New Jersey college students found that those who had ever indoor tanned scored higher on a healthy (e.g., eliminating snacking, eating less fat, less high calorie foods, more fruits and vegetables) dietary behavior scale [26]. Similarly, Harland and colleagues found that eating fruits or vegetables at least four times in the prior day was associated with a higher likelihood of lifetime indoor tanning among male (but not female) Canadian high school students [18]. Using 2009 and 2011 YRBSS data, Guy and colleagues found that among male (but not female) high school students, those who indoor tanned in the past year were more likely to engage in heathy dietary practices such as eating fruits or vegetables at least five times per day in the past week [22]. In one of the YRBSS studies using 2009 data, Miyamoto and colleagues found that male high school students that ate fruits or vegetables at leastfive times per day in the past week had a higher odds of indoor tanning in the past year [21].

No significant association with dietary practices.

Only one publication by Choi and colleagues taking data from the 2005 HINTS found that attempting to lose weight in the past year did not appear to be associated with indoor tanning in the past year in either men or women [12]. It is important to note that these data were from a sample of white individuals from the U.S. aged 18-64, whereas most other papers focus on adolescent or young adult populations.

DISCUSSION

One key motivation to indoor tan and to diet or exercise is appearance enhancement. People primarily indoor tan because they believe they look better and even feel better with tanned skin [27]. Similarly, with diet and exercise, some individuals are attempting to make themselves more attractive by staying in shape or be within their ideal weight range by attempting to lose or maintain weight [2, 5]. Thus, we hypothesized that individuals with lower BMIs, higher physical activity, and dieters would be more likely to report indoor tanning. The primary findings of this review indicated that recent (in the last year) or past indoor tanning was associated with high physical activity, playing on sports teams, or weight control via various methods. However, there are a few noted discrepancies.

There were seemingly contrasting reports on BMI and its relationship to indoor tanning. Being classified as overweight was associated with either a greater or lesser likelihood of indoor tanning, and several studies found no association. One issue is that papers classified weight categories differently from one another in some cases. One paper attributed the finding of a higher BMI being associated with indoor tanning to overweight high school students’ feeling uncomfortable exposing their bodies to the sun in public, and therefore, opting for the privacy offered by indoor tanning salons [16]. This is further highlighted by the finding that students in the underweight BMI group were more likely to tan outdoors than those in the BMI group classified as overweight [16]. Adolescents who are classified as overweight may also feel that a tan helps them look slimmer [16]. However, one of the papers that found adolescents classified as overweight less likely to indoor tan posited that these adolescents may be uncomfortable entering tanning facilities [14]. The findings remain inconsistent when examining them by sex. Only one study examined the association between obesity and tanning dependence, a topic that should be investigated further [28].

With regard to physical activity in general, indoor tanners were more likely to describe themselves as more physically active and report longer durations of exercise [13, 18]. This is a notable finding because melanoma is one of the cancers found to be significantly associated with higher (90th percentile or higher) vs. lower (10th percentile or lower) levels of leisure-time physical activity in a meta-analysis of 12 very large prospective US or European cohorts [29]. This is likely due to receipt of ultraviolet radiation and/or sunburns during outdoor exercise [29]. However, indoor tanning may also play a role in the higher melanoma risk among frequent exercisers. Typically, physical activity and skin cancer prevention interventions are not coordinated with one another and can even be perceived as at odds with people being encouraged to exercise outside with no mention of sun protection. There have been calls to integrate such interventions [30, 31].

There was only one study that compared team sports to individual sports [23]. The authors found that German adults engaging in individual-based sports such as aerobics or strength training were more likely to use sunbeds than those doing team sports, martial arts, or those who did not participate in sports at all [23]. The authors note that this may be of significance, as tanning beds are often associated with gyms, where users would be likely to participate in such individual sports [23]. One policy intervention that has been mentioned in the literature is removing tanning beds from health-oriented businesses such as gyms [32, 33]. Strength training and aerobics are also sports that are in part focused on outward appearance in terms of building lean muscle or burning fat; whereas, team-based sports have objectives that may be more focused on social interaction, competition, or having fun. The appearance of strength trainers is particularly scrutinized. Thus, the positive association between physical activity and indoor tanning may be explained by the common motive of appearance enhancement. Though people who exercise are often also interested in their health, the damaging health effects of indoor tanning, which typically are not seen until later in life, may be underestimated due to the immediate rewards of perceived appearance enhancement. Finally, the study by Cartmel and colleagues appears to be the first study to demonstrate an association between exercise and tanning addiction, which raises the possibility of a common addictive mechanism for both excessive exercise and tanning [17]. Interventions could attempt to recruit indoor tanners at athletic venues such as gyms, races, and other sporting events.

Indoor tanning was associated with weight control by using either potentially healthy or unhealthy dietary methods. Vomiting, using laxatives or pills, or taking un-prescribed steroids to control weight are unhealthy diet methods with known deleterious side effects that were found to be associated with indoor tanning in several studies of adolescents using large national datasets [20–22, 25]. However, the results from the YRBSS studies may have differed slightly from one another because different covariates were included in the multivariable models. Some potentially healthy behaviors that were noted to be associated with indoor tanning included fruit and vegetable consumption [18, 19, 21, 22, 26]. Of the papers addressing dieting to lose weight, some of the individuals trying to lose weight were not overweight to begin with, and it is unknown whether they had any dietary supervision from a healthcare provider. Furthermore, there was not additional information provided in terms of dieting methods employed such as calorie or fat reduction and whether participants were still consuming healthy recommended levels of various food groups and nutrients. Moreover, classifying someone as having a healthy diet based upon the fact that they eat more fruits and vegetables may not be appropriate given additional associations found between indoor tanning and greater fast food, soft drink, as well as supplement and meal replacement consumption among Canadian adolescents [18]. The healthiness of “dieting” behaviors among some children and adolescents, who were the population of interest in most of the studies, is also questionable. Thus, it is unclear whether some of these dieting behaviors were associated with an overall healthy diet or not.

It is interesting to note that among the male high school students in the 2009 YRBSS study, Blashill found that frequent indoor tanning was related to a motivation to gain weight, rather than to lose weight [24]. This may be attributed to the difference in appearance-based goals between male and female adolescents. For example, young men may cite a desire to gain weight in terms of lean muscle mass, which is supported by the additional positive association with non-prescription steroid use [24]. On the other hand, young women are more likely to internalize the need to appear “thin”, and therefore, are more likely to report weight-loss attempts [34]. Sex or age differences in associations with indoor tanning were not consistent across studies. Nevertheless, the motivation of most tanners and both healthy and unhealthy dieters may be to improve their outward appearance. These motivations and behaviors are in line with body image theories such as objectification theory in which individuals, primarily women and girls, are acculturated to be concerned with observers’ views of their bodies [35]. Interventions based on body image could target multiple health behaviors simultaneously such as restrictive eating and tanning. Other theoretical models, such as emotion regulation and social norms/comparison, may also be informative.

Examining only studies focusing on frequent indoor tanning shows a more consistent association with unhealthy dietary behaviors. However, the two studies that investigated tanning dependence and BMI or physical activity differed in their findings [15, 17]. Notably, no studies focusing on diagnosed eating disorders were identified; though there are several studies addressing eating disorders and psychosocial (rather than behavioral) issues around weight, diet, and exercise (e.g., [36, 37]). Individuals, particularly adolescents and young adults, with appearance or weight concerns and unhealthy dietary practices should also be targeted concerning potential indoor tanning as part of other lifestyle interventions.

The strengths of this review lie in the systematic selection of publications and inclusion of reports from local, regional, national, and international samples, most comprised of large sample sizes. However, there are some important limitations. All of the papers included were survey-based and relied on self-reported data, which may be susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall bias. In addition to being self-report, there are other weaknesses with some of the measures. For example, BMI does not account for body type, thus sometimes characterizing muscular individuals as obese. Moreover, most studies were focused on adolescents and adults under age 45, with the exception of the 2005 HINTS study by Choi and colleagues [12] and our 2005 NHIS studies [11, 19], which limits generalization to adult indoor tanners. However, while the number of papers including older age groups is limited, indoor tanners are often adolescents or young adults anyway [38]. Additionally, a number of papers reviewed included data from the YRBSS. While these results are drawn from a large nationally representative sample, the YRBSS was only distributed to students enrolled in public or private high-schools at the time, so the findings may not apply other groups such as homeschooled adolescents or those who were no longer enrolled in school. In addition, the YRBSS survey was only concerned with indoor tanning in the past year and dieting practice in the past thirty days, limiting conclusions regarding longitudinal trends and causality. There were no consistent patterns in the findings depending on whether the timeframe was past year or lifetime indoor tanning. There are studies that examined more unique populations, such as adolescents in the Virginia or Texas area or only one sex, which limits generalization to larger populations [14, 15, 23, 29]. Lastly, it is not possible to ascertain from these data whether or not some of these behaviors become habits that follow students into adulthood, or if they are time-limited experimental behaviors of adolescence.

In summary, indoor tanning was found to be associated high levels of physical activity, playing on sports teams, and attempted weight control by various healthy or unhealthy methods. The findings of this review highlight a possible paradox among the behaviors of study participants. Behaviors that are typically considered healthy such as increased physical activity or participation in sports are coupled with unhealthy indoor tanning. In the pursuit of an outward appearance of attractiveness, health, and well-being, the individuals involved may be discounting the potential negative health consequences of indoor tanning [28]. This is probably due to strong pressure and/or a desire for appearance enhancement and not primarily to a lack of knowledge since indoor tanners tend to be aware of the major risks of indoor tanning [39]. Attempts to alter beauty norms and de-emphasize societal focus on appearance are ongoing challenges [35, 40].

Future research should include increased representation from non-adolescents and investigate the longitudinal relationship of indoor tanning to the variables of interest as well as potential demographic differences (e.g., sex, age). In addition to advocating for evidence-based restrictions on indoor tanning, particularly for minors [41], health professionals should attempt to identify frequent tanners and be aware of the relationships among indoor tanning and other health-related factors such as unhealthy weight control and over-exercising. Given the clear relationship between indoor tanning and appearance-based motivations, interventions should encourage healthy body image and not only promote cessation of unhealthy behaviors but adoption of healthy alternatives such as sunless tanning, healthy nutrition and physical activity, and evidence-based and professionally-guided weight-loss programs for those who are truly at an unhealthy weight. Along those same lines, due to the common co-occurrence of risky health behaviors [42], there has been increasing interest in multiple behavior change interventions [43–48]. However, how and when those are most effectively employed are ongoing research questions [49]. Studies exploring interventions for both indoor tanning and healthy eating, physical activity, or weight management are needed.

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank Mary Riley for her assistance with manuscript preparation and Kristen Sorice for her review and feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Funding:

This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (P30CA006927, P30CA072720).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed consent: For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Contributor Information

Carolyn J. Heckman, Cancer Prevention and Control, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey

Marissa Manning, Medical Student, Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Qin J, Holman DM, Jones SE, Berkowitz Z, Guy GP Jr. State Indoor Tanning Laws and Prevalence of Indoor Tanning Among US High School Students, 2009-2015. Am. J. Public Health 2018;108(7):951–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2018.304414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Santos I, Sniehotta FF, Marques MM, Carraca EV, Teixeira PJ. Prevalence of personal weight control attempts in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2017;18(1):32–50. doi: 10.1111/obr.12466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman B, English JC 3rd, Ferris LK. Indoor Tanning, Skin Cancer and the Young Female Patient: A Review of the Literature. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol 2015;28(4):275–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiala B, Kopp M, Gunther V. Why do young women use sunbeds? A comparative psychological study. Br. J. Dermatol 1997;137(6):950–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berczik K, Szabo A, Griffiths MD, et al. Exercise addiction: symptoms, diagnosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Substance use & misuse. 2012;47(4):403–17. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.639120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razzoli M, Pearson C, Crow S, Bartolomucci A. Stress, overeating, and obesity: Insights from human studies and preclinical models. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews. 2017;76(Pt A):154–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.01.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landolfi E Exercise Addiction. Sports Med. 2013;43(2):111–9. doi: 10.1007/s40279-012-0013-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams Merten J, King JL, Walsh-Childers K, Vilaro MJ, Pomeranz JL. Skin Cancer Risk and Other Health Risk Behaviors: A Scoping Review. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 2015;11(2):182–96. doi: 10.1177/1559827615594350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chinn S A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat. Med 2000;19(3):3127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Durlak JA. How to Select, Calculate, and Interpret Effect Sizes. J. Pediatr. Psychol 2009;34(9):917–28. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsp004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coups EJ, Manne SL, Heckman CJ. Multiple skin cancer risk behaviors in the U.S. population. American journal of preventive medicine. 2008;34(2):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Choi K, Lazovich D, Southwell B, Forster J, Rolnick SJ, Jackson J. Prevalence and characteristics of indoor tanning use among men and women in the United States. Arch. Dermatol 2010;146(12):1356–61. doi:146/12/1356 [pii] 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer MKH, Koster B, Juul L, et al. Sunbed use among 64,000 Danish students and the associations with demographic factors, health-related behaviours, and appearance-related factors. Prev. Med 2017;100:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demko CA, Borawski EA, Debanne SM, Cooper KD, Stange KC. Use of indoor tanning facilities by white adolescents in the United States. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med 2003;157(9):854–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Wilson DB, Ingersoll KS. A preliminary investigation of the predictors of tanning dependence. American Journal of Health Behav. 2008;32(5):451–64. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.5.451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoo J-J, Kim H-Y. Adolescents’ body-tanning behaviours: influences of gender, body mass index, sociocultural attitudes towards appearance and body satisfaction. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 2012;36(3):360–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1470-6431.2011.01009.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartmel B, Bale AE, Mayne ST, et al. Predictors of tanning dependence in white non-Hispanic females and males. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol 2017;31(7):1223–8. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harland E, Griffith J, Lu H, Erickson T, Magsino K. Health behaviours associated with indoor tanning based on the 2012/13 Manitoba Youth Health Survey. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice. 2016;36(8):149–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heckman CJ, Coups EJ, Manne SL. Prevalence and correlates of indoor tanning among US adults. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol 2008;58(5):769–80. doi:S019-9622(08)00132-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Riordan DL, Field AE, Geller AC, et al. Frequent tanning bed use, weight concerns, and other health risk behaviors in adolescent females (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(5):679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyamoto J, Berkowitz Z, Jones SE, Saraiya M. Indoor tanning device use among male high school students in the United States. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2012;50(3):308–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guy GP Jr., Berkowitz Z, Tai E, Holman DM, Everett Jones S, Richardson LC. Indoor tanning among high school students in the United States, 2009 and 2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(5):501–11. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.7124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diehl K, Litaker DG, Greinert R, Zimmermann S, Breitbart EW, Schneider S. The prevalence of current sunbed use and user characteristics: the SUN-Study 2008. International journal of public health. 2010;55(5):513–6. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0100-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blashill AJ. Psychosocial correlates of frequent indoor tanning among adolescent boys. Body Image. 2013;10(2):259–62. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amrock SM, Weitzman M. Adolescent indoor tanning use and unhealthy weight control behaviors. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2014;35(3):165–71. doi: 10.1097/dbp.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gillen MM, Markey CH. Beauty and the burn: tanning and other appearance-altering attitudes and behaviors. Psychology, health & medicine. 2017:1–7. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1330544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holman DM, Watson M. Correlates of intentional tanning among adolescents in the United States: a systematic review of the literature. The Journal of adolescent health : official publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. 2013;52(5 Suppl):S52–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckman CJ, Wilson DB, Ingersoll KS. The influence of appearance, health, and future orientations on tanning behavior. Am J Health Behav. 2009;33(3):238–43. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2009.33.3.238 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore SC, Lee I, Weiderpass E, et al. Association of leisure-time physical activity with risk of 26 types of cancer in 1.44 million adults. JAMA internal medicine. 2016;176(6):816–25. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran AD, Aalborg J, Asdigian NL, et al. Parents’ perceptions of skin cancer threat and children’s physical activity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E143. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jardine A, Bright M, Knight L, Perina H, Vardon P, Harper C. Does physical activity increase the risk of unsafe sun exposure? Health promotion journal of Australia : official journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals. 2012;23(1):52–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagoto SL, Nahar VK, Frisard C, et al. A comparison of tanning habits among gym tanners and other tanners. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(9):1090–1. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang CM, Kirchhof MG. A Cross-Sectional Study of Indoor Tanning in Fitness Centres. J. Cutan. Med. Surg 2017;21(5):401–7. doi: 10.1177/1203475417706059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Darlow SD, Heckman CJ, Munshi T. Tan and thin? Associations between attitudes toward thinness, motives to tan and tanning behaviors in adolescent girls. Psychology, health & medicine. 2016;21(5):618–24. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1093643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fredrickson BL, Roberts T-A. Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1997;21(2):173–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petit A, Karila L, Chalmin F, Lejoyeaux M. Phenomenology and psychopathology of excessive indoor tanning. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(6):664–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwebel DC. Adolescent tanning, disordered eating, and risk taking. Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP. 2014;35(3):225–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider S, Kramer H. Who uses sunbeds? A systematic literature review of risk groups in developed countries. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010;24(6):639–48. doi:JDV3509 [pii] 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knight JM, Kirincich AN, Farmer ER, Hood AF. Awareness of the risks of tanning lamps does not influence behavior among college students. Archives of dermatology. 2002;138(10):1311–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brouse CH, Hillyer GC, Basch CE, Neugut AI. Geography, facilities, and promotional strategies used to encourage indoor tanning in New York City. J. Community Health 2011;36(4):635–9. doi: 10.1007/s10900-010-9354-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seidenberg AB, Mahalingam-Dhingra A, Weinstock MA, Sinclair C, Geller AC. Youth indoor tanning and skin cancer prevention: lessons from tobacco control. Am. J. Prev. Med 2015;48(2):188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meader N, King K, Moe-Byrne T, et al. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC public health. 2016;16:657. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3373-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meader N, King K, Wright K, et al. Multiple Risk Behavior Interventions: Meta-analyses of RCTs. Am. J. Prev. Med 2017;53(1):e19–e30. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Knight A, Shakeshaft A, Havard A, Maple M, Foley C, Shakeshaft B. The quality and effectiveness of interventions that target multiple risk factors among young people: a systematic review. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2017;41(1):54–60. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Webb MJ, Kauer SD, Ozer EM, Haller DM, Sanci LA. Does screening for and intervening with multiple health compromising behaviours and mental health disorders amongst young people attending primary care improve health outcomes? A systematic review. BMC family practice. 2016;17:104. doi: 10.1186/s12875-016-0504-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green AC, Hayman LL, Cooley ME. Multiple health behavior change in adults with or at risk for cancer: a systematic review. Am J Health Behav. 2015;39(3):380–94. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.39.3.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hale DR, Fitzgerald-Yau N, Viner RM. A systematic review of effective interventions for reducing multiple health risk behaviors in adolescence. Am. J. Public Health 2014;104(5):e19–41. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2014.301874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Busch V, de Leeuw JR, de Harder A, Schrijvers AJ. Changing multiple adolescent health behaviors through school-based interventions: a review of the literature. J. Sch. Health 2013;83(7):514–23. doi: 10.1111/josh.12060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.James E, Freund M, Booth A, et al. Comparative efficacy of simultaneous versus sequential multiple health behavior change interventions among adults: A systematic review of randomised trials. Prev. Med 2016;89:211–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]