Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus C55 was shown to produce bacteriocin activity comprising three distinct peptide components, termed staphylococcins C55α, C55β, and C55γ. The three peptides were purified to homogeneity by a simple four-step purification procedure that consisted of ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by XAD-2 and reversed-phase (C8 and C18) chromatography. The yield following C8 chromatography was about 86%, with a more-than-300-fold increase in specific activity. When combined in approximately equimolar amounts, staphylococcins C55α and C55β acted synergistically to kill S. aureus or Micrococcus luteus but not S. epidermidis strains. The N-terminal amino acid sequences of all three peptides were obtained and staphylococcins C55α and C55β were shown to be lanthionine-containing (lantibiotic) molecules with molecular weights of 3,339 and 2,993, respectively. The C55γ peptide did not appear to be a lantibiotic, nor did it augment the inhibitory activities of staphylococcin C55α and/or C55β. Plasmids of 2.5 and 32.0 kb are present in strain C55, and following growth of this strain at elevated temperature (42°C), a large proportion of the progeny failed to produce strong bacteriocin activity and also lost the 32.0-kb plasmid. Protoplast transformation of these bacteria with purified 32-kb plasmid DNA regenerates the ability to produce the strong bacteriocin activity.

Research into the production of antibiotic-like activities by Staphylococcus aureus dates back well into the last century (8). Several groups demonstrated that bacteriocin production was especially common in S. aureus phage group II, particularly in strains of phage type 71 (5, 23). Dajani et al. (6) partially purified an inhibitory agent from tryptic soy broth cultures of S. aureus C55, a strain that they adopted as the prototype of the phage group II bacteriocin producers. The purification protocol essentially involved ammonium sulfate precipitation followed by gel filtration on Sephadex G-100. The spectrum of inhibitory activity of the agent was shown to be similar to that of bacteriocins produced by other gram-positive bacteria in that it included strains of a wide variety of other gram-positive genera. Of interest was the finding that 21 of 31 S. aureus strains but none of 18 strains of S. epidermidis appeared to be sensitive to the inhibitor (6). Mode-of-action studies indicated that cell death was due to pore formation in the cytoplasmic membrane and widespread inhibition of macromolecular biosynthesis following exposure to the partially purified material (7).

Among the most thoroughly studied staphylococcal bacteriocins in recent years are the S. epidermidis products epidermin (1), Pep5 (25), and epilancin (33). All of these are classified as lantibiotics, i.e., low-molecular-weight, posttranslationally modified peptides containing the distinctive amino acids lanthionine and/or β-methyllanthionine and sometimes dehydro amino acids (29). As a consequence of these modifications, the processed, biologically active lantibiotics are relatively short, flexible, and thermally stable molecules. Several other bacteriocins isolated from S. epidermidis have subsequently been shown to be either epidermin or epidermin variants (9, 14, 26). There appears to be only a single report to date of lantibiotic production by S. aureus (31). Amino acid sequencing of this molecule, named staphylococcin Au-26, showed that there was an isoleucine residue at the N terminus followed by a sequencing-blocking residue in position 2.

In one recent study, a heat-stable, broadly active bacteriocin with a molecular mass of 6,418 Da was isolated from S. aureus KSI1829 and partially characterized (3). More recently, the same group has partially characterized another broad-spectrum S. aureus bacteriocin, namely, staphylococcin BacR1 (4, 23). BacR1 had a mass of 3,338 Da, and analysis of its amino acid composition suggested a large number of glycine residues and a relatively high proportion of hydrophobic amino acids.

Enhanced bactericidal effects due to the complementary activity of two peptides has been described for some bacteriocin complexes, including lactococcin G (20), plantaricin A (21), and plantaricin S (16). Similarly, cytolysins CylLL and CylLS produced by Enterococcus faecalis have also been reported to complement each other in antibacterial activity (10). This dual-peptide system is unique in that both component molecules have been identified as lantibiotics.

In the present study, we have re-examined the nature of the bactericidal activity of S. aureus C55 and demonstrated that three antibacterial peptides are produced. Two of these peptides, staphylococcins C55α and C55β, were shown to be lantibiotic molecules that act synergistically to kill strains of S. aureus but not S. epidermidis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, maintenance of cultures, and detection of antibacterial activity.

The parent inhibitor-producing strain is the phage group II type 71 strain S. aureus C55 described by Dajani and Wannamaker (5). Strain C55c is a derivative of C55 isolated following growth of the parent strain at 42°C in tryptic soy broth (Difco). C55c differs from C55 in the absence of a 32.0-kb plasmid and in the markedly reduced width of the inhibition zone that it produces against Micrococcus luteus T-18 in simultaneous-antagonism tests on Columbia agar base (CAB; GIBCO, Ltd., Paisley, United Kingdom). Strain T-18 is routinely used in this laboratory as a sensitive indicator of bacteriocin activity (24). S. aureus UT0007 was obtained from Pat Schlievert, University of Minnesota. All of the staphylococcal strains used to assess the activity spectrum of strain C55 were obtained from our laboratory culture collection and maintained at 4°C on CAB with 4% human blood (blood agar) when in regular use.

Antibacterial activity was assessed by spotting 20-μl drops of twofold serial dilutions (in phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] at pH 6.5) of the test preparation on the surface of CAB (15). When the drops had dried into the agar, the surface of the plate was exposed to chloroform vapor for 30 min and then, after airing for 15 min, an overnight Todd-Hewitt broth culture of M. luteus T-18 was swabbed evenly over the surface. Following overnight incubation at 37°C, the highest dilution of the test sample to clearly inhibit the growth of the indicator lawn was said to contain 1 arbitrary unit (AU) of bacteriocin/ml (15).

Purification of the inhibitory peptides.

A 10-ml overnight culture of strain C55 was inoculated into 800 ml of tryptic soy broth (Difco) and then divided into two 1-liter flasks for incubation at 37°C with shaking at 160 rpm for 18 h. The cells were removed by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 min, and ammonium sulfate was then slowly added to the supernatant to achieve 60% saturation. The precipitated material was collected by centrifugation and redissolved in 400 ml of PBS (pH 6.5). This preparation was applied to an XAD-2 (Serva, Heidelberg, Germany) column with a bed volume of 500 ml equilibrated in 1 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.5). The column was washed with 3 bed volumes of 1 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.5), followed by 4 bed volumes of 70% methanol containing 1 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.5). These fractions were discarded. Inhibitory activity was recovered from the column by washing with 2 bed volumes of 90% methanol (adjusted to pH 2 with 11.6 M HCl) and concentrated by evaporation at 50°C under reduced pressure. Aliquots (1 ml) of this material were applied to a Brownlee C8 reversed-phase column (Aquapore RP 300; pore size, 7 μm; 30 by 4.6 mm; Applied Biosystems, Inc.) equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). Fractionation of the material was achieved by application of a stepped gradient (0 to 40% acetonitrile containing 0.085% TFA) using a Pharmacia fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) system at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. Each 1-ml fraction was tested for inhibitory activity against M. luteus T18. Inhibitory activity was detected in three distinct regions of the eluent fluid, and the active fractions in each region were separately pooled and named A, B, and C. Each pool was lyophilized and then dissolved in 0.1% TFA. Aliquots of each of these preparations were then loaded onto a C18 reversed-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) column (Alltech Nucleosil C18; 10 μm; 250.0 by 4.6 mm) equilibrated with 0.1% TFA and further fractionated by using a Waters/Millipore HPLC system by application of appropriate gradients of acetonitrile: for staphylococcin C55α, this was 24 to 29% acetonitrile over 60 min, and for staphylococcin C55β, it was 28 to 34% acetonitrile over 60 min. Inhibitory activity was detected by the CAB spot diffusion test using M. luteus T-18 as the indicator. For some assays, subinhibitory amounts of peptide pool A, B, or C were added to the individual column eluent fractions to potentially increase the sensitivity of the assay due to synergistic inhibitory activity between particular combinations of peptides. The amounts of protein in samples were determined by the modified Lowry method (22).

Electrophoresis.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) was performed by using HPLC-purified preparations of staphylococcins C55α and C55β. The preparations of staphylococcin C55γ used for SDS-PAGE were obtained by lyophilization of active fractions from C8 FPLC separations. A Mini-Protean II electrophoresis system (Bio-Rad, Richmond, Calif.) with 16.5% tricine gels (Bio-Rad) and the tricine buffer system was utilized as described by Schägger and Jagow (28). Following electrophoresis, the gels were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 (Sigma). Localization of inhibitory peptides was achieved by overlayering the gels with a thin film of CAB seeded with M. luteus T-18 and then incubating them to allow inhibitory zones to develop within the growing indicator lawn.

Antibacterial spectrum of strains C55 and C55c.

The antibacterial spectrum of strains C55 and C55c was determined by using the deferred-antagonism test (15, 32). After overnight growth of S. aureus C55 as a 1-cm-wide diametric streak culture on CAB, the growth was removed and the agar surface was sterilized with chloroform vapor as described above. The strains to be tested for sensitivity to C55 products were swabbed across the line of the original streak by using overnight Todd-Hewitt broth cultures. After 18 h of incubation, any interference with the growth of the indicator in the vicinity of the original diametric growth zone was considered to be due to inhibitory agents produced by the C55 culture.

Synergy assays.

HPLC-purified staphylococcin C55α and C55β preparations were assayed for inhibitory activity by the agar diffusion test. Stock 4 μM preparations of each peptide were prepared in distilled water by using lyophilized, HPLC-purified material. Assessment of the amount of protein was done by amino acid analysis. A series containing differing proportions of the two peptides was prepared in a microtiter tray, and 20-μl samples (and twofold PBS [pH 6.5] dilutions of these samples) were then spotted onto CAB plates, dried, and seeded as described above with M. luteus T-18 to detect the amount of inhibitory activity.

Plasmid DNA isolation and protoplast transformation.

Plasmid DNA was purified from strains C55 and C55c by using a commercial plasmid preparation kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) as described previously (34). For large-scale plasmid extraction, a QIAGEN-tip 100 column was used. Transformation of strain C55c with plasmid DNA from strain C55 was done by using the protoplast transformation method described by Götz and Schumacher (11). Protoplasts were regenerated in modified DM 3 agar, and overlayers of soft agar containing M. luteus were used to detect transformants.

Peptide analysis.

Amino acid compositions, mass spectrometry, and N-terminal amino acid sequencing were done by the Protein Microchemistry Facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Otago. The amino acid compositions of phenylthiocarbamyl derivatives were determined by using a narrow-bore binary reversed-phase HPLC system (12). Determination of lanthionine or β-methyllanthionine was done by use of the o-phthaldialdehyde method (26). Mass spectrometry was done with matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass analyzer (Finnigen Lasermat 2000; Thermo Bioanalysis), and N-terminal amino acid sequencing was done by automated Edman degradation on a 470A pulsed liquid protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems Inc.) (13).

To enable Edman degradation to proceed through blockages caused by the presence of dehydro amino acids, these residues were first modified by addition of thiol groups by using a modification of the method described by Meyer et al. (18). Lyophilized peptide preparations were incubated under N2 at 50°C for 3 h with 200 μl of 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 10) containing 30% (wt/vol) 2-mercaptoethanol. The resulting product was diluted 1:1 with 2% TFA and applied to a Prosorb sample preparation cartridge (Perkin Elmer). After being washed three times with 0.1% TFA, the membrane was dried and sequencing was done as described above.

RESULTS

Production and recovery of inhibitory activity.

C55 cultures grown at 37°C in tryptic soy broth gave a reliable yield of inhibitory activity. Increased production over that recovered from unshaken cultures was obtained when the cultures were rotated at 160 rpm. Decreased recovery was obtained beyond 18 h of incubation, indicating some possible stationary growth phase degradation of the inhibitory activity.

Purification of antibacterial peptides.

The first step toward purification of the inhibitory agents from tryptic soy broth culture supernatants involved the use of an ammonium sulfate precipitation step. Subsequent binding of the inhibitory agents to XAD-2 resins was greatly enhanced by introduction of this procedure. Elution of the inhibitory peptides bound to XAD-2 was effected by washing with 90% methanol (pH 2). The total inhibitory activity following the XAD-2 step was not significantly less than the total activity present in the original culture supernatant (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Stepwise purification of staphylococcin C55 peptides α, β, and γ

| Purification step | Protein (mg) | Inhibitory activity (AU) | Sp act (AU/mg) | Yield (%) | Times purified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant (0.8 liter) | 192.8 | 19,200 | 100 | 100 | 1 |

| Ammonium sulfate precipitation | 114.6 | 19,600 | 172 | 102 | 1.72 |

| XAD chromatography | 28.0 | 18,400 | 657 | 96 | 6.57 |

| C8 FPLC | 0.33, 0.2, 0.22b | 16,540,a 304c | 32,960 | 86 | 329.6 |

Based on the inhibitory activity detected when peptides α and β were combined in equimolar amounts.

Peptides α, β, and γ, respectively.

Peptide γ alone.

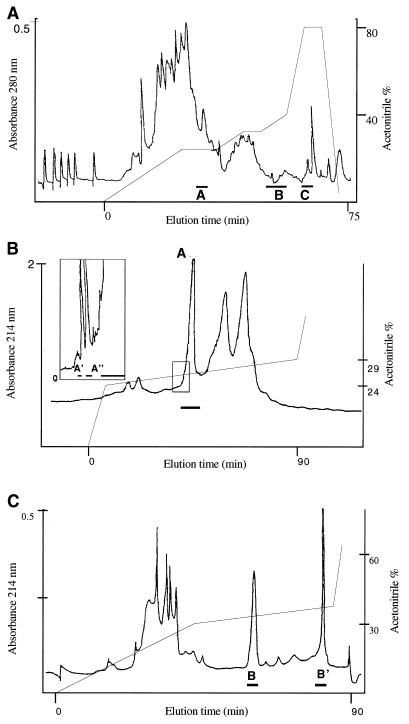

By contrast, considerable apparent loss of activity was noticed during C8 reversed-phase FPLC. Inhibitory activity against the indicator M. luteus was detected in three well-separated clusters of fractions, i.e., pools A, B, and C (Fig. 1). By combining samples from pools A and B, a marked increase in inhibitory activity was obtained; however, there was no increase in inhibitory activity following addition of aliquots of either pool A or B to pool C. Furthermore, no activity increase was obtained when aliquots of pool A, B, or C were added to samples from the C8 eluent fractions that had initially lacked inhibitory activity against M. luteus.

FIG. 1.

(Panel A) C8 reversed-phase chromatography elution profile of a C55 preparation obtained by XAD-2 chromatography of culture supernatant. Protein material eluted in an acetonitrile gradient was detected by A280 measurement, and the inhibitory activity of each 1-ml fraction was tested against M. luteus T-18. Solid bars A, B, and C represent the inhibitory fractions. (Panels B and C) C18 reversed-phase HPLC analysis of the A and B inhibitory fractions obtained by FPLC (as shown in panel A). Protein material eluted in an acetonitrile gradient was detected by A214 determination, and the inhibitory activity of each fraction was tested against M. luteus T-18. In addition to major peak A, two minor peaks (A′ and A") on the leading edge of peak A were found to have inhibitory activity against M. luteus T-18. Two peaks B (B and B′) had inhibitory activity against M. luteus T-18 (shown by the solid bars).

When peptide pool A was subjected to C18 reversed-phase HPLC, some inhibitory activity was associated with minor peaks A′ and A" in addition to that found in major peak A (Fig. 1). By contrast, the inhibitory activity recovered on C18 chromatography of peptide pool B (Fig. 1) was associated with two well-separated peaks (B and B′) and could only be detected after concentration of the pooled peak fractions by 10-fold lyophilization. Alternatively, inhibitory activity could be detected in these fractions without concentration if they were tested in the presence of low (subinhibitory) levels of material from FPLC peak A or HPLC peak A, A′, or A".

No activity could be detected following C18 fractionation of material from pool C even when testing of the eluent fractions was done in the presence of subinhibitory concentrations of FPLC pools A and/or B. A sample of FPLC pool C material gave a single band (molecular mass of ca. 1,500 Da) when run on 16% tricine SDS-PAGE. Inhibitory activity was associated specifically with this band when the sample was overlayered with M. luteus-containing CAB. HPLC peak A material gave a single band on SDS-PAGE, and two separate bands with masses of ca. 6,000 and 9,000 Da were found in HPLC peak B samples, possibly indicating the formation of covalent dimers and trimers of the peptide.

Inhibitory activity against staphylococci.

The range of inhibitory activity of strain C55 against staphylococci was determined by using the deferred-antagonism test. With the exception of one strain of S. carnosus, none of 52 coagulase-negative staphylococci was inhibited by strain C55 in these tests. By contrast, 120 strains of S. aureus, including several multiantibiotic-resistant and mupirocin-resistant strains, were strongly inhibited. Only two S. aureus strains were resistant to strain C55 in these tests. Both belonged to phage group II, and both appeared to produce inhibitory activities closely similar to that produced by strain C55, as judged by the identical inhibitory profiles given by all three strains in deferred-antagonism tests and by the nonsusceptibility (or immunity) that each exhibited to its own inhibitory products and to the products of the other two strains. By contrast, strain C55c (see later), an inhibitor-deficient derivative of strain C55, exhibited partial sensitivity to all three phage group II producer strains in deferred-antagonism tests.

Synergistic activity of staphylococcins C55α and C55β.

When HPLC-purified preparations of staphylococcins C55α and C55β (peaks A and B, respectively) were tested for inhibitory activity, this was only evident for C55α. When drops of both preparations were placed adjacent to one another in a CAB assay, an enhanced zone of inhibition was produced in the region between the C55α and C55β preparations (Fig. 2). When purified peptide preparations were mixed in different concentrations, a marked increase in inhibitory activity was noticed when the peptides were present at equimolar concentrations (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Synergistic inhibitory activity demonstrated on CAB when paper discs containing purified preparations of C55α (left) and C55β (right) were placed on a growing lawn culture of M. luteus T-18.

TABLE 2.

Inhibitory activities of mixtures of staphylococcins C55α and C55β against M. luteus T-18

| % of mixturea

|

Sp act (AU/ml) | Increase in activity (fold)b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | ||

| 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 90 | 256 | 32 |

| 20 | 80 | 512 | 64 |

| 30 | 70 | 512 | 64 |

| 40 | 60 | 1,024 | 128 |

| 50 | 50 | 1,024 | 128 |

| 60 | 40 | 512 | 64 |

| 70 | 30 | 512 | 64 |

| 80 | 20 | 128 | 16 |

| 90 | 10 | 8 | 1 |

| 100 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

The total volume of the mixtures was 30 μl.

Activity of the mixture divided by the activity of 100% C55α.

Mass spectrometry.

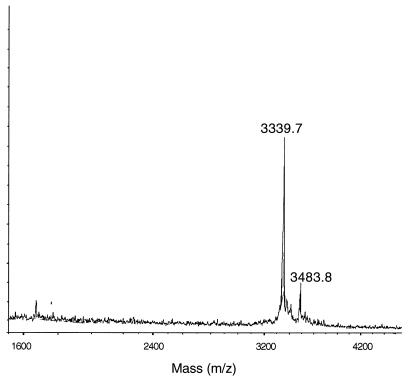

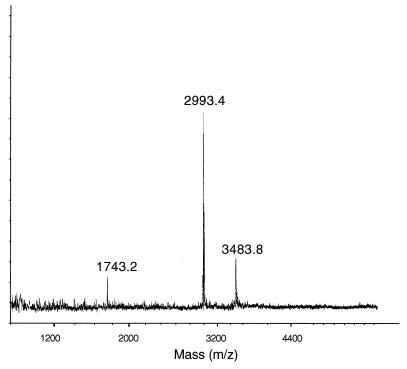

HPLC-purified staphylococcin C55α and C55β each gave clean single peaks corresponding to masses of 3,339.7 ± 0.3 and 2,993.4 ± 0.4 Da, respectively (Fig. 3 and 4).

FIG. 3.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of staphylococcin C55α. Glucagon (molecular mass of 3,482.8 Da) was used as the internal standard. An average molecular mass of 3,339.7 ± 0.3 Da was calculated.

FIG. 4.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry of staphylococcin C55β. Glucagon (molecular mass of 3,482.8 Da) was used as the internal standard. An average molecular mass of 2,993.4 ± 0.4 Da was calculated.

Amino acid composition.

Table 3 shows the predicted amino acid compositions of C55α and C55β. Only the unmodified amino acids are listed, since the modified amino acids were not identifiable by their phenylthiocarbamyl derivatives. Both peptides were confirmed to contain lanthionine and/or β-methyllanthionine by the o-phthaldialdehyde method.

TABLE 3.

Amino acid compositions of staphylococcins C55α and C55β

| Amino acida | Estimated no. of residues/molecule

|

|

|---|---|---|

| C55α | C55β | |

| Asp or Asn | 4 | 1 |

| Glu or Gln | 3 | 1 |

| Ser | 0–1 | 0 |

| Gly | 2 | 5 |

| His | 1 | 0 |

| Arg | 0 | 1 |

| Thr | 0 | 2 |

| Ala | 2 | 5 |

| Pro | 2–3 | 2 |

| Tyr | 0 | 1 |

| Val | 1 | 2 |

| Met | 0 | 0 |

| Ile | 0 | 2 |

| Leu | 2 | 3 |

| Phe | 1 | 0 |

| Lys | 2 | 0 |

| Lanthionine or β-methyllanthionine | 3 | 3 |

Trp was not determined. The number of amino acid residues was determined from the molar ratio relative to Val (for C55α) and Arg (C55β) by taking into account the molecular mass that had been derived for each peptide. Lanthionine and/or β-methyllanthionine was detected by the o-phthaldialdehyde method (26).

Protein sequence analysis.

Staphylococcins C55α and C55β were subjected to automated Edman degradation to determine their N-terminal amino acid sequences. The first two residues were not clearly detected in C55α, and the third residue was blocked, suggesting the presence of a dehydro amino acid residue, which is a characteristic feature of lantibiotics. Digestion with chymotrypsin was not successful in giving any additional sequencing information (results not shown), but modification by using mercaptoethanol successfully unblocked the residue in position 3 and enabled further sequencing through to the 18th residue as follows: Xaa-Xaa-Dhb-Asn-Xaa-Phe-Dha-Leu-Xaa-Asp-Tyr-Trp-Gly-Asn-Lys-Gly-Asn-Trp-Xaa-Xaa-Ala-Ala. The third residue was clearly identified as Dhb, because of its characteristic chromatographic profile (27). Xaa indicates cycles in which no known amino acid derivative was detected.

Initial attempts to sequence C55β showed glycine to be the first residue, but there was a 95% loss of yield in the second cycle, again indicative of dehydro amino acid blockage. Mercaptoethanol modification of the peptide enabled the following sequence to be obtained: Gly-Dhb-Xaa-Leu-Ala-Leu-Leu-Gly-Gly-Ala-Ala-Dhb-Gly-Val-Ile-Gly-Tyr-Ile-Xaa-Asn-Gln-Thr-Xaa-Pro. N-terminal sequencing of peptide C identified the following 16 residues with no evidence that any sequence-blocking residues were present: Met-Gly-Ile-Ile-Ala-Gly-Ile-Ile-Xaa-Xaa-Ile-Lys-Leu-Ile-Glu-Xaa-Phe-Thr-Thr.

Plasmid curing studies and protoplast transformation.

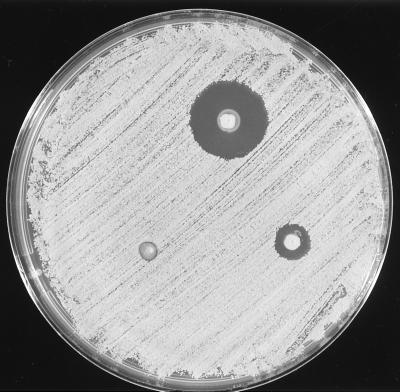

S. aureus C55 contains two plasmids with sizes of approximately 32.0 and 2.5 kb. Incubation of tryptic soy broth cultures of strain C55 at 42°C for 18 h resulted in widespread (>90% of those tested) loss of the ability to produce large zones of inhibitory activity when individual CAB-grown colonies subcultured from these 42°C cultures were tested against M. luteus in simultaneous-antagonism stab tests (Fig. 5). Examination of the plasmid contents of representative inhibitor-deficient clones showed that they had all lost the 32.0-kb plasmid but not the 2.5-kb plasmid. Strain C55c was adopted as a representative inhibitor-deficient, 32-kb plasmid-“cured” derivative of strain C55. Strain C55c differed from the parent C55 in that it failed to inhibit the growth of strains of S. aureus in either simultaneous- or deferred-antagonism tests. Protoplast transformation of strain C55c by using purified 32-kb plasmid DNA resulted in regeneration of the ability to produce levels of staphylococcins C55α and C55β that were inhibitory to S. aureus. By contrast, all attempts to convert S. carnosus to inhibitor production by protoplast transformation met with failure.

FIG. 5.

Simultaneous-antagonism inhibitory zones produced in a lawn of M. luteus T-18 by stab cultures of S. aureus C55 (top), C55c, a “cured” derivative of strain C55 (bottom right), and strain 46 (an unrelated bacteriocin-negative isolate) (bottom left).

DISCUSSION

This study has identified three peptides (staphylococcins C55α, C55β, and C55γ) that are responsible for the inhibitory activity of S. aureus C55. The homogeneity of the purified staphylococcin C55α and C55β preparations was established by reversed-phase HPLC, mass spectrometry, and amino acid sequencing. It was also shown that these two peptides act synergistically to inhibit the growth of strains of M. luteus and S. aureus. By contrast, there was no evidence of antibacterial interaction of staphylococcin C55γ with either C55α or C55β. Purified staphylococcins C55α and C55β by themselves had only relatively weak activity against the most sensitive indicator, M. luteus T-18. Combination of similar quantities of C55α and C55β increased inhibitory activity by 128-fold. Inhibitory activity against S. aureus was only detected in combinations of the two peptides.

One of the main problems in determining the amino acid sequences of lantibiotics is the frequent presence of dehydro amino acids in these molecules, leading to blocking of the Edman degradation reaction. The usual method of proteolytic digestion to obtain peptide fragments for sequencing does not always give helpful results due to the presence of lanthionine or β-methyllanthionine rings, which can further alter the arrangement of the peptide or interfere with its enzymatic digestion. Combination of Edman degradation and mass spectroscopy following alkaline ethanethiol treatment was successfully applied to determine the amino acid sequences of nisin and Pep5 (18). More recently, the mutacin B-Ny 266 sequence was also resolved by use of the same treatment (19). In the present study, both staphylococcins C55α and C55β were successfully “unblocked” by use of mercaptoethanol treatment. Oligonucleotide probes based upon the sequences of staphylococcins C55α and C55β have now been used to detect the structural genes of both peptides in strain C55 and have confirmed the amino acid sequencing results (unpublished data).

The two additional well-separated peaks having inhibitory activity that eluted from the C18 column in close association with the staphylococcin C55α peak probably represent variants of the predominant peptide molecule. Similarly, staphylococcin C55β preparations appear to contain another variant of the molecule (peptide C55β′). The estimated masses of these additional peaks were 3,356.5 and 3,009.0 Da, respectively (data not shown in Results), and are thought to represent oxidized or incompletely dehydrated forms of staphylococcins C55α and C55β that are nevertheless still capable of interfering with the growth of M. luteus. The amount of these additional peptides recovered was not enough to enable comparison of their specific activities (arbitrary units per milligram) or any further characterization of the molecules.

The genetic determinants of previously characterized staphylococcal bacteriocins have been either plasmid or chromosome associated (2, 17, 30). In the current study, it has been shown that a 32.0-kb plasmid is required for the production of staphylococcins C55α and C55β. As strain C55c displays greater sensitivity than parent strain C55 to the inhibitory products of strain C55 in deferred-antagonism tests or to an equimolar mixture of staphylococcins C55α and C55β (results not shown), it is presumed that some immunity to both of these bacteriocins is also conferred upon the cell by 32.0-kb plasmid-encoded gene products. The inability to obtain inhibitor-producing transformants of S. carnosus following protoplast transformation with 32-kb plasmid DNA from strain C55 may be due to either a lethal effect of the bacteriocins or the incompatibility of the plasmid with this S. carnosus strain. Due to our failure to identify any other marker which could be used to detect the presence of this plasmid, we were unable to establish the efficiency of the transformation process.

Crupper et al. have recently reported the purification of BacR1 from S. aureus UT0007 (4). The molecular mass of BacR1 was reported to be 3,338 Da, a size close to that of staphylococcin C55α. This suggests the possibility that the same peptide has been independently isolated in the two studies. The blockage to Edman degradation encountered in the attempted sequencing of BacR1 hints at the presence of a dehydro amino acid similar to that found in staphylococcin C55α. The possibility exists that the five residues obtained on sequencing BacR1 may be of a contaminating peptide species due to sequencing blockages occurring at the N terminus of the BacR1 molecule. We have cross-tested strains UT0007 (the producer of BacR1) and C55 and have found that each is immune to the inhibitory products of the other. Furthermore, an oligonucleotide probe specific for the N-terminal sequence of staphylococcin C55α was found to bind to 32.0-kb plasmid DNA present in both strains C55 and UT0007 (results not shown). The marked loss of inhibitory activity reported by Crupper et al. on reversed-phase chromatography of BacR1 may be due to the inadequate sensitivity of the Corynebacterium renale indicator strain used in that study for detection of inhibitory activity equivalent to that of staphylococcin C55β. The individual components of the bacteriocin cluster reported here to be produced by S. aureus C55 may possibly be found in other staphylococcal strains. We are currently using oligonucleotide probes specific for staphylococcins C55α, C55β, and C55γ to examine the extent of the distribution of the corresponding structural genes throughout the genus Staphylococcus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from the Health Research Council of New Zealand. The studies by M. A. D. B Navaratna in Bonn, Germany, were made possible with the support of travel grants from the German Ministry for Research and Technology (BMBF) through DLR.

Thanks are due to Clive Ronson for advice and to Ralph Jack, Diana Carne, Alan Carne, and Robin Simmonds for help with purification of the peptides.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgaier H, Jung G, Werner R G, Schneider U, Zähner H. Epidermin: sequencing of a heterodet tetracyclic 21-peptide amide antibiotic. Eur J Biochem. 1986;160:9–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09933.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustin J, Rosenstein R, Wieland B, Schneider U, Schnell N, Engelke G, Entian K-D, Götz F. Genetic analysis of epidermin biosynthetic genes and epidermin-negative mutants of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Eur J Biochem. 1992;204:1149–1154. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crupper S S, Iandolo J J. Purification and partial characterization of a novel antibacterial agent (Bac1829) produced by Staphylococcus aureus KSI1829. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3171–3175. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3171-3175.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crupper S S, Gies A J, Iandolo J J. Purification and characterization of staphylococcin BacR1, a broad-spectrum bacteriocin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4185–4190. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4185-4190.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dajani A S, Wannamaker L W. Demonstration of a bactericidal substance against β-hemolytic streptococci in supernatant fluids of staphylococcal cultures. J Bacteriol. 1969;97:985–991. doi: 10.1128/jb.97.3.985-991.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dajani A S, Gray E D, Wannamaker L W. Bactericidal substance from Staphylococcus aureus. Biological properties. J Exp Med. 1970;131:1004–1015. doi: 10.1084/jem.131.5.1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dajani A S, Wannamaker L W. Kinetic studies on the interaction of bacteriophage type 71 staphylococcal bacteriocin with susceptible bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1973;114:738–742. doi: 10.1128/jb.114.2.738-742.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Florey H W, Chain E, Heatley N G, Jennings M A, Sanders A G, Abraham E P, Florey M E, editors. The antibiotics. Vol. 1. London, England: Oxford University Press; 1949. Antibiotics from bacteria; pp. 417–565. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frey A, Kellner R, Jung G, Sahl H-G. Frequency of lantibiotic production among coagulase-negative staphylococci: re-isolation of epidermin. In: Jung G, Sahl H-G, editors. Nisin and novel lantibiotics. Leiden, The Netherlands: Escom Publishers; 1991. pp. 180–188. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilmore M S, Skaugen M, Nes I. Enterococcus faecalis cytolysin and lactocin S of Lactobacillus sake. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;69:129–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00399418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Götz F, Schumacher B. Improvements of protoplast transformation in Staphylococcus carnosus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;40:285–288. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubbard M J. Calbindin28kDa and calmodulin are hyperabundant in rat dental enamel cells. Identification of protein phosphatase calcineurin as a calmodulin target and of a secretion-related role for calbindin28kDa. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:68–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hubbard M J, McHugh N J. Mitochondrial ATP synthase F1-β-subunit is a calcium-binding protein. FEBS Lett. 1996;391:323–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00767-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Israil A M, Jack R W, Jung G, Sahl H-G. Isolation of a new epidermin variant from two strains of Staphylococcus epidermidis—frequency of lantibiotic production in coagulase-negative staphylococci. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1996;284:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(96)80104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jack R W, Tagg J R. Factors affecting production of the group A streptococcus bacteriocin SA-FF22. J Med Microbiol. 1992;36:132–138. doi: 10.1099/00222615-36-2-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiménez-Díaz R, Ruiz-Barba J L, Cathcart D P, Holo H, Nes I F, Sletten K H, Warner P J. Purification and partial amino acid sequence of plantaricin S, a bacteriocin produced by Lactobacillus plantarum LPCO10, the activity of which depends on the complementary action of two peptides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:4459–4463. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.12.4459-4463.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaletta C, Entian K-D, Kellner R, Jung G, Reis M, Sahl H-G. Pep5, a new lantibiotic: structural gene isolation and prepeptide sequence. Arch Microbiol. 1989;152:16–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00447005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer H E, Heber M, Eisermann B, Korte H, Metzger J W, Jung G. Sequence analysis of lantibiotics: chemical derivatization procedures allow a fast access to complete Edman degradation. Anal Biochem. 1994;223:185–190. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mota-Meira M, Lacroix C, LaPointe G, Lavoie M C. Purification and structure of mutacin B-Ny266: a new lantibiotic produced by Streptococcus mutans. FEBS Lett. 1997;410:275–279. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nissen-Meyer J, Holo H, Havarstein L S, Sletten K, Nes I F. A novel lactococcal bacteriocin whose activity depends on the complementary action of two peptides. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5686–5692. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.17.5686-5692.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nissen-Meyer J, Larsen A G, Sletten K, Daeschel M, Nes I F. Purification and characterization of plantaricin A, a Lactobacillus plantarum bacteriocin whose activity depends on the action of two peptides. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:1973–1978. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-9-1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson G L. A simplification of the protein assay method of Lowry et al. which is more generally applicable. Anal Biochem. 1977;83:346–356. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rogolsky M, Wiley B B. Production and properties of a staphylococcin genetically controlled by the staphylococcal plasmid for exfoliative toxin synthesis. Infect Immun. 1977;15:726–732. doi: 10.1128/iai.15.3.726-732.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross K F, Ronson C W, Tagg J R. Isolation and characterization of the lantibiotic salivaricin A and its structural gene salA from Streptococcus salivarius 20P3. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2014–2021. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2014-2021.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahl H-G, Brandis H. Production, purification and chemical properties of an antistaphylococcal agent produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Gen Microbiol. 1981;127:377–384. doi: 10.1099/00221287-127-2-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sahl H-G. Staphylococcin 1580 is identical to the lantibiotic epidermin: implications for the nature of bacteriocins from gram-positive bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:752–755. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.752-755.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scaloni A, Barra D, Bossa F. Sequence analysis of dehydroamino acid-containing peptides. Anal Biochem. 1994;218:226–228. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schägger H, Jagow G V. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schnell N, Entian K D, Schneider U, Götz F, Zähner H, Kellner R, Jung G. Prepeptide sequence of epidermin, a ribosomally synthesized antibiotic with four sulphide-rings. Nature (London) 1988;333:276–278. doi: 10.1038/333276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schnell N, Entian K D, Götz F, Horner T, Kellner R, Jung G. Structural gene isolation and prepeptide sequence of gallidermin, a new lanthionine containing antibiotic. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;49:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott J C, Sahl H-G, Carne A, Tagg J R. Lantibiotic-mediated anti-lactobacillus activity of a vaginal Staphylococcus aureus isolate. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;93:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90496-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tagg J R, Bannister L V. “Fingerprinting” β-haemolytic streptococci by their production of and sensitivity to bacteriocine-like inhibitors. J Med Microbiol. 1979;12:397–411. doi: 10.1099/00222615-12-4-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van de Kamp M, Horstink L M, van den Hooven H W, Konings R N H, Hilbers C W, Frey A, Sahl H-G, Metzger J W, van de Ven F J. Sequence analysis by NMR spectroscopy of the peptide lantibiotic epilancin K7 from Staphylococcus epidermidis K7. Eur J Biochem. 1995;227:757–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vriesema A J M, Zaat S A J, Dankert J. A simple procedure for isolation of cloning vectors and endogenous plasmids from viridans group streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3527–3529. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3527-3529.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]