Abstract

The koji mold Aspergillus oryzae secretes a prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase (DPPIV) when the fungus is cultivated in a medium containing wheat gluten as the sole nitrogen and carbon source (MMWG). We cloned and sequenced the DPPIV gene from an A. oryzae library by using the A. fumigatus dppIV gene as a probe. Reverse transcriptase PCR experiments showed that the A. oryzae dppIV gene consists of two exons, the first of which is only 6 bp long. The gene encodes an 87.2-kDa polypeptide chain which is secreted into the medium as a 95-kDa glycoprotein. Introduction of this gene into A. oryzae leads to overexpression of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity, while disruption of the gene abolishes all prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity in MMWG. The dppIV null mutants did not exhibit any change in phenotype other than the absence of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity, suggesting that this activity is not essential. This loss of activity diminished the number of dipeptides and increased the number of larger peptides present in the MMWG culture broth. These effects were reversed by the addition of purified, recombinant DPPIV from the methylotrophic yeast expression vector Pichia pastoris. Our results suggest that the DPPIV enzyme may be of importance in industrial hydrolysis of what gluten-based substrates, which are rich in Pro residues.

Aspergillus oryzae and the closely related Aspergillus sojae are used in industrial and traditional koji fermentations. During such fermentation, these molds secrete a large variety of carbohydrases and proteases that are essential for efficient solubilization and hydrolysis of the soybean or wheat raw materials. Protein degradation is a complex multistep process involving endopeptidases and exopeptidases (14). To date, two neutral endopeptidases (NPI and NPII) (28, 29), an alkaline endopeptidase (ALP) (24, 30) and an aspartic protease (PEPO) (49, 50) have been identified and purified from koji molds. The genes encoding NPII (48), ALP (10, 47), and PEPO (5) from A. oryzae have been cloned and characterized. The exopeptidases characterized in A. oryzae are aminopeptidases (31–33, 39), carboxypeptidases (25–27, 34), and a prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase (46). Since wheat gluten contains a large number of Pro residues (1), this last enzyme could be of particular importance in the degradation of wheat gluten during koji fermentation.

Recently, two dipeptidyl peptidase genes (dppIV and dppV) from Aspergillus fumigatus have been cloned and characterized (3, 4). The dppIV gene encodes a prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase (DPPIV) which releases N-terminal X-Pro residues, while the dppV gene encodes a dipeptidyl peptidase (DPPV) which releases N-terminal X-Ala, His-Ser, and Ser-Tyr dipeptides. DPPIV activity previously detected in A. oryzae (46) was probably due to an enzyme homologous to the A. fumigatus DPPIV. To date, the role of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity has not been analyzed in the context of fermentation and hydrolysis of wheat gluten (WG) by A. oryzae. Our objectives were to clone the A. oryzae gene encoding DPPIV and to compare the peptide profiles of a WG-containing medium hydrolyzed by wild-type or dppIV disruptant strains.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli LE392 was used as a host strain for propagation of bacteriophages. Plasmid pMTL21-H4.6, containing the A. fumigatus dppIV gene that was used as a probe, was kindly provided by A. Beauvais, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France. Plasmids pMTL20 (9), pNEB 193 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), pBluescript SK− (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.), and pCL1920b (6) were used in subcloning procedures. E. coli DH5α was transformed by using competent cells and standard protocols (43).

Both A. oryzae 44 and TK3 from our strain collection were used as the wild type. A. oryzae NF1 is a uridine auxotroph derived from TK3 by targeted disruption (51) and was used as the recipient for transformations. Plasmid pNFF28 containing the A. oryzae TK3 pyrG gene (P. van den Broek; GenBank accession no. Y13811) was used as a selection marker in the cotransformation experiment to overexpress DPPIV in A. oryzae. Aspergillus nidulans 033 (biA1 argA1) was obtained from A. J. Clutterbuck, Fungal Genetic Stock Centre, Glasgow, Scotland. A. fumigatus CBS 144.89 and Aspergillus niger CBS 126.49 were used to test secreted prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity.

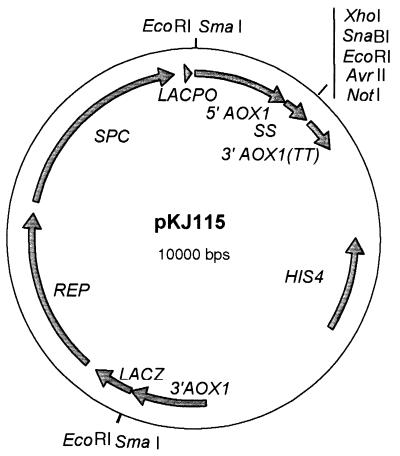

The E. coli-Pichia pastoris shuttle vector pPIC9 was obtained by using the P. pastoris expression system from Invitrogen (San Diego, Calif.). The P. pastoris expression vector pKJ115 was constructed by cloning the expression cassette of pPIC9, flanked by two BglII sites, in the BamHI site of pCL1920b. In pKJ115, the expression cassette of pPIC9 was flanked by two SmaI sites for linearization of the DNA, before transformation of P. pastoris GS115 (Fig. 1). The His− Mut+ P. pastoris strain GS115, used as a host for transformation, was obtained from Invitrogen.

FIG. 1.

Map of plasmid pKJ115. REP, pCL1920 replicon (19); SPC, spectinomycin resistance gene; LACPO, LACZ promoter; 5′ AOX1, P. pastoris alcohol oxidase gene (AOX1) promoter; SS, signal peptide sequence of α factor; 3′ AOX1(TT), AOX1 terminator; HIS4, P. pastoris histidinol dehydrogenase gene; 3′ AOX1, 3′ AOX1 downstream sequence; LACZ, pUC19 LACZ fragment.

A. oryzae growth media.

Aspergillus minimal medium (MM) was prepared as described by Pontecorvo et al. (40). Wheat gluten minimal medium (MMWG) contained MM and 1% (wt/vol) WG (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). Wheat gluten-wheat gluten hydrolysate minimal medium (MMWGH) contained MM, 0.1% (wt/vol) WG (Sigma), and 0.1% (wt/vol) WG hydrolysate (WGH). WGH was prepared by hydrolyzing nonvital WG powder (Roquette, Freres, Lestrem, France) with alcalase (Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark). This preparation used a 20% (wt/wt) substrate concentration and an enzyme-to-substrate ratio of 1:50 (weight of protein) for 6 h at 60°C and a constant pH of 7.5. Alcalase was then heat inactivated at 90°C for 10 min. After centrifugation of the hydrolysate, the supernatant was lyophilized to give WGH and stored at room temperature. It contained mainly peptides that were shown by size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex peptide HR 10/30 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) (data not shown) to be in the range of 200 to 10,000 Da. Only minimal amounts of free amino acids were detected.

Genomic DNA extraction of A. oryzae.

Genomic DNA from lyophilized mycelium was isolated as described by Raeder and Broda (41) and purified by using Genomic-tips (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Cloning and sequencing of the A. oryzae dppIV gene.

The A. oryzae genomic library was constructed in λEMBL3 as previously described (23). Recombinant plaques of the A. oryzae 44 genomic library were immobilized on nylon membranes (Genescreen; Biotechnology Systems, Boston, Mass.). These filters were probed for 20 h with the 32P-labeled 2.3-kb dppIV insert of pMTL21-H4.6 amplified by PCR (4) under low-stringency conditions (5× SSC solution [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate] containing 20% formamide, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], and 10% dextran sulfate at 42°C). DNA was labeled by use of a random-primed DNA labeling kit (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany) and [α-32P]dATP. The membranes were then exposed to X-ray film after two 20-min washes in 3× SSC–1% SDS at 40°C. Positive plaques were purified, and the associated bacteriophage DNAs were isolated as described by Grossberger (15).

The nucleotide sequence of the dppIV gene was determined on a Licor model 4000 automatic sequencer (MWG-Biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). Infrared dye (IRD41)-labeled primers were used for sequencing both strands of partially overlapping subclones by the dideoxynucleotide method of Sanger et al. (44). The DNA sequence was analyzed with the Genetics Computer Group computer program (13).

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR).

Total RNA was isolated from A. oryzae TK3 mycelium cultured overnight on MMWGH by using an RNeasy total RNA purification kit (for plants and fungi) (Qiagen). RT-PCR was performed by using a 1st Strand cDNA synthesis kit for RT-PCR (Boehringer). Briefly, 10 μg of total RNA, 1× reaction buffer (10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl [pH 8.3]), 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM deoxynucleotide mix, 1.6 μg of oligo-poly(dT)15 primer, 50 U of RNase inhibitor, and 10 U of avian myeloblastosis virus RT were mixed and incubated at 25°C for 10 min, at 42°C for 60 min, at 75°C for 5 min, and, finally, at 4°C for 5 min. Two microliters of the cDNA suspension obtained, 1 μl of oligonucleotides at a 50 μM concentration each, and 1 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates at 10 mM each (Boehringer) were dissolved in 50 μl of PCR buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.55), 16 mM (NH4)2SO4, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 150 μg of bovine serum albumin per ml]. To each reaction mixture, 1.5 U of Taq polymerase (Biotaq; Bioprobe, Montreuil, France) and 1 drop of Nujol mineral oil (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) were also added. The targeted region of the dppIV gene was amplified by using a Stratagene Robo Cycler gradient 40, with the primers 3372 and 3373 (Table 1). The reaction mixtures were subjected to 2 cycles of 1 min at 98°C, 2 min at 56°C, and 2 min at 72°C, followed by 27 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 56°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and 1 cycle of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 56°C, and 10 min at 72°C. The gel-purified PCR products were recovered with Qiaex II (Qiagen) and directly ligated into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Madison, Wis.) to generate plasmid pNFF137.

TABLE 1.

List of PCR primers used in this work

| PCR product | Primer | Primer sense | Oligonucleotide sequence | Targeted DNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. oryzae 5′ dppIV fragment (bp −6 to +692) | 3372 | Sense | 5′-TCC ACC ATG AAG TAC TCC-3′ | A. oryzae cDNA obtained by RT |

| 3373 | Antisense | 5′-ATC GCC GAG GAT CTC CTC-3′ | ||

| A. oryzae dppIV mature protein-encoding fragment (bp +132 to +2399) | 3261 | Sense | 5′-TG GTC GAT ATC CTG GAT GTG CCT CGG AAA CCA-3′ | pNFF125 |

| 3260 | Antisense | 5′-G TTG CGG CCG CTA CTC CTC CAA GTC CTT CTT-3′ | ||

| Functional A. nidulans pyrG gene | 3158 | Sense | 5′-GAA TTC GAG CCG TCA GTG AGG CTC-3′ | A. nidulans genomic DNA |

| 3159 | Antisense | 5′-GA ATT CCA TGG TGT CCT CGT CGT CGG-3′ |

Southern blotting.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of total A. oryzae genomic DNA was blotted onto nylon membranes (Hybond-N+; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) in accordance with the standard protocol (43). The membranes were prehybridized at 65°C for 45 min in Rapid-hyb buffer (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) before hybridization for 5 h in the same solution containing random-primed 32P-labeled probes. The membranes were exposed to X-ray film after three washes in 0.1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 65°C. Densitometric scans of autoradiographs were obtained by using the Herolab GmbH (Wiesloch, Germany) Enhanced Analysis System.

Standard PCRs.

Two hundred nanograms of DNA, 1 μl of oligonucleotides each at 50 mM, and 6 μl of deoxynucleoside triphosphates each at 2 mM were dissolved in 50 μl of PCR buffer number 2 [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.8), 2 mM MgSO4, 10 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Triton X-100, 100 μg of nuclease-free bovine serum albumin per ml) to which a drop of Dynawax (Finnzymes, Espoo, Finland) was then added. To each reaction mixture, 2.5 U of cloned Pfu DNA polymerase (Stratagene) in 50 μl of 1× PCR buffer was added. These reaction mixtures were subjected to 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 52°C, and 3 min at 72°C with a Perkin-Elmer DNA thermal cycler.

A. oryzae transformation.

A. oryzae NF1 was transformed as previously described (12). The A. nidulans pyrG gene and the A. oryzae pyrG gene were used as the selection markers in A. oryzae dppIV gene disruption and overexpression, respectively. Transformants were selected on MM.

Enzyme assays.

For in situ detection of DPPIV activity, spores of the test strains were resuspended in 200 μl of SP2 buffer (20 mM KH2PO4 adjusted to pH 2.0 with HCl and 0.9% NaCl) in microtiter plates and replica plated onto petri dishes containing MMWGH covered by a filter (Chr1; Whatman, Maidstone, England). The plates were then incubated for 2 days at 30°C. DPPIV activity was detected on the filter by the methods of Lojda (20) and Aratake et al. (2). The filters were reacted with a solution containing 3.0 mg of glycyl proline 4-β-naphthylamide in 0.25 ml of N,N-dimethylformamide and 5.0 mg of o-dianisidine, tetrazotized in 4.6 ml of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 10 min at room temperature.

DPPIV activity was determined in culture broth by UV spectrometry with the synthetic substrate alanine-proline-p-nitroanilide (Bachem, Bübendorf, Switzerland) as described by Sarath et al. (45). Fifty microliters of substrate stock solution in 10 mM dimethyl sulfoxide was diluted with 900 μl of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Fifty microliters of culture broth was added, and the reaction was continued for up to 60 min at 37°C. A control experiment with blank substrate and blank culture broth was carried out in parallel. Release of the chromophoric group p-nitroaniline was measured at 400 nm, and activities were expressed as milliunits per milliliter (nanomoles per minute per milliliter). For practical purposes, 1 U of DPPIV activity was defined as the activity producing an absorbance of 0.01 min−1 in a proteolytic assay at optimum pH.

Expression of the A. oryzae dppIV gene in P. pastoris.

The plasmid used to express the A. oryzae dppIV gene in P. pastoris was constructed by cloning a PCR product of the dppIV gene in the multiple-cloning sites of the E. coli-P. pastoris shuttle vector pKJ115. In detail, the A. oryzae dppIV coding region was amplified by standard PCR with primers 3261 and 3260 (Table 1). The PCR product was purified with the High Pure PCR product purification kit (Boehringer) and then digested by EcoRV and NotI restriction enzymes for which a site was previously designed at the 5′ extremity of the primers. By using standard protocols (43), the digested PCR products were then cloned into the SnaBI and NotI sites of the pPIC9 cassette multiple-cloning site of plasmid pKJ115.

Spheroplasts of P. pastoris were transformed with 10 μg of DNA linearized by SmaI. Transformants were selected on histidine-deficient medium (1 M sorbitol, 1% [wt/vol] dextrose, 1.34% [wt/vol] yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.00004% [wt/vol] biotin, 0.005% amino acids [i.e., 0.005% {wt/vol} of each l-glutamic acid, l-methionine, l-lysine, l-leucine, l-isoleucine]) and screened for insertion of the construct at the AOX1 site on methanol-minimal plates (1.34% [wt/vol] yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, 0.00004% [wt/vol] biotin, 0.5% [vol/vol] methanol).

Transformants unable to grow on media containing only methanol as a carbon source were assumed to contain the construct at the correct yeast genomic location and to have resulted from integration events in the AOX1 locus displacing the AOX1 coding region. The selected transformants were grown to near saturation at 30°C in 10 ml of glycerol-based yeast medium (BMGY; 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer [pH 6.0], containing 1% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] peptone, 1.34% [wt/vol] YNB without amino acids, 1% [vol/vol] glycerol, and 0.00004% [wt/vol] biotin). Cells were harvested and resuspended in 2 ml of the same medium with 0.5% (vol/vol) methanol instead of glycerol (BMMY) and incubated for 2 days, after which time the supernatant was harvested and 10 μl was loaded on SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels to identify clones producing DPPIV.

Purification of DPPIV produced by P. pastoris.

Ten milliliters of centrifuged culture broth was ultrafiltered on a Centricon-10 filter unit (Amicon, Beverly, Mass.) to a final volume of 2.5 ml. This aliquot was loaded onto a PD-10 column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and eluted with 3.5 ml of distilled water. The eluate was loaded onto a second column containing 500 mg of hydroxylapatite (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.), and the protein was eluted by a sodium phosphate buffer gradient (50 to 250 mM) at pH 7.0. In a typical experiment, approximately 500 μg of pure, active DPPIV was recovered; this corresponds to a yield of about 54%.

Treatment with N-glycosidase F.

Four milliliters of culture broth containing secreted prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase from an overproducing strain was ultrafiltered on a Centricon-50 filter unit (Amicon) to a final volume of 112 μl. Approximately 50 μg of DPPIV was diluted in a solution of 25 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 25 mM EDTA, and 0.15% SDS and then heated at 100°C for 5 min. After the solution cooled, 10% Nonidet P-40 and 0.6 U of N-glycosidase F (Boehringer) were added (final detergent concentrations, 0.1% SDS and 0.5% Nonidet P-40) and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 20 h. The reaction was stopped by adding SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer, followed by incubation at 100°C for 5 min.

N-terminal sequence determination of deglycosylated DPPIV from A. oryzae.

After SDS-PAGE, protein bands were directly blotted with a Mini Trans-Blot unit (Bio-Rad) onto an Immobilon PSQ (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) membrane and visualized by staining with Coomassie blue R-250. After the membrane was air dried, DPPIV-containing bands were excised with a razor blade. In situ automated Edman degradation for N-terminal sequence analysis was performed on the blot with a gas-phase sequencer (model 477A; PE Applied Biosystems), equipped for on-line detection of the amino acids released.

Peptide profiling.

A. oryzae wild-type strain TK3 and A. oryzae disruptant D1 were grown in parallel in 200 ml of MMWG for 7 days at 30°C without shaking. The cultures were then filtered through two layers of cheesecloth. To 500-μl aliquots of culture medium was added either 3 μg of purified DPPIV (around 320 mU) or 20 μl of enzyme buffer without DPPIV. The aliquots were incubated for 24 h at 37°C, heated at 95°C for 10 min, centrifuged, and analyzed by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex peptide HR 10/30 column. Separation of the amino acids and peptides from treated culture broth aliquots was based on molecular size (range, 100 to 7,000 Da). Chromatography was performed under isocratic conditions with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid–20% acetonitrile in water at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. Amino acid and peptide peaks were detected at 215 nm. Peptide and amino acid standards were used to calibrate the chromatographic system (data not shown), and an Ala-Pro (Biochem) dipeptide solution (0.2 mg/ml) was used as a Pro-containing dipeptide control.

RESULTS

DPPIV activity secreted by wild-type aspergilli.

A. oryzae 44 and TK3 exhibited similar DPPIV activities on MMWGH plates. In a typical experiment, a total of about 10 U of DPPIV activity was produced in 1 liter of liquid MMWG after 7 days of growth at 30°C. This experiment thus confirmed previous studies reporting the secretion of DPPIV by A. oryzae strains (46). We also observed DPPIV activity on MMWGH plates in A. fumigatus and A. nidulans but not in A. niger (data not shown).

Cloning of A. oryzae dppIV gene.

A 2.3-kb DNA PCR fragment encompassing the coding region of the A. fumigatus dppIV gene (4) was used for low-stringency screening of 4 × 104 recombinant plaques from the A. oryzae 44 genomic λEMBL3 library. Of these, 10 positive clones were isolated and purified. Restriction enzyme analysis of purified bacteriophage DNA revealed that the clones carried similar but not identical DNA fragments. By Southern analysis, the dppIV gene was assigned to an ApaI-EcoRV 4.8-kb fragment (data not shown), which was then subcloned into pBluescript SK− to generate the plasmid pNFF125.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the A. oryzae dppIV gene.

The nucleotide sequence of the 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV insert from pNFF125 was determined on both strands (accession no. AJ002369) and compared to that of the gene encoding the DPPIV of A. fumigatus. One of the three open reading frames, as determined by the nucleotide sequence of A. fumigatus dppIV, was examined and revealed a colinear intron-exon structure between the A. oryzae cloned gene and A. fumigatus dppIV (3). It consisted of two exons, the first of which was only 6 bp long. The intron-exon structure of the putative A. oryzae dppIV gene was verified by RT-PCR using the 5′ primer 3372 to bridge the putative intron and the 3′ primer 3373. A fragment of 594 bp was amplified from the total RNA from mycelium after growth for 24 h in MMWGH. A PCR using the same primers performed on A. oryzae TK3 genomic DNA yielded no amplification product (data not shown) and served as the negative control. Sequence analysis of the PCR fragment confirmed the presence of a 6-bp-long exon and an 83-bp-long intron. Based on the nucleotide sequence of the cDNA obtained by RT-PCR, the putative A. oryzae DPPIV appeared to be encoded by 2,313 nucleotides starting from the ATG codon. The deduced amino acid sequence of A. oryzae DPPIV aligned with that of A. fumigatus DPPIV with 76.7% similarity and 69.8% identity.

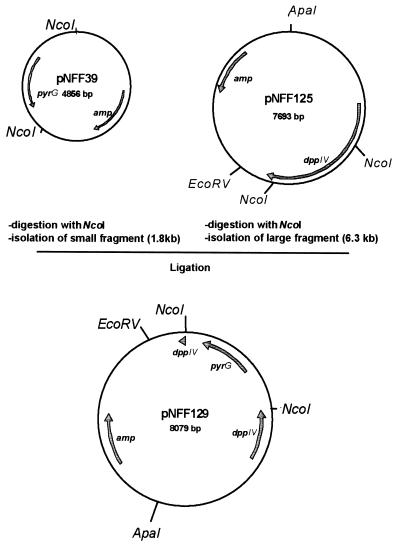

Disruption of the dppIV gene.

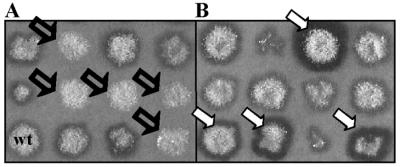

The dppIV gene was disrupted in A. oryzae TK3 to determine whether all prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity observed in MMWGH originated from the cloned gene. Sequences between positions 500 and 2342 of the A. nidulans pyrG gene (37) were amplified by standard PCR using the primers 3159 and 3158 (Table 1) and the 1.8-kb PCR product cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) to generate pNFF39. The internal 1.5-kb NcoI fragment in pNFF125 was replaced by the 1.8-kb NcoI fragment from pNFF39 (Fig. 2), creating the dppIV disruption construct pNFF129. A. oryzae NF1 was transformed with ApaI-EcoRV-digested pNFF129, and transformants were selected on MM. Prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity was not detected in 22 of 95 transformants after 2 days of incubation at 30°C on solid MMWGH medium (Fig. 3A) or in liquid MMWG culture medium after 7 days at the same temperature.

FIG. 2.

Construction of plasmid pNFF129 used for dppIV gene disruption. The 1.5-kb NcoI fragment of pNFF125 containing an internal part of the A. oryzae dppIV gene was replaced with the 1.8-kb NcoI fragment from pNFF39 containing the functional A. nidulans pyrG gene.

FIG. 3.

Screening of A. oryzae dppIV null mutants (open arrows) (A) and DPPIV overproducers (solid arrows) (B).

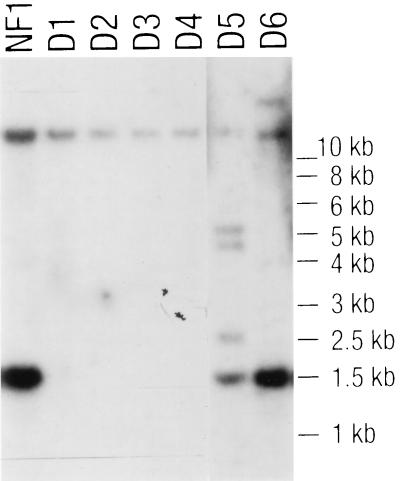

Southern blot analysis (Fig. 4) was performed on NcoI-digested genomic DNA from four prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase-negative transformants (transformants D1 to D4) and two transformants that retained the activity (D5 and D6) by using a dppIV probe obtained by standard PCR using primers 3260 and 3261 (Table 1). Two hybridizing bands were observed by using NF1 DNA; the larger 12-kb fragment contained the promoter region and the region encoding the 243 amino acids at the N terminus of the DPPIV protein. The 1.5-kb NcoI fragment contains the part of the dppIV gene that has been replaced by the functional pyrG gene in pNFF129. The signal for the 1.5-kb fragment is absent in the NcoI restriction pattern of transformants which did not exhibit DPPIV activity (D1 to D4), indicating that the wild-type gene had been replaced by the disruption construct. Transformants D5 and D6, which retained DPPIV activity, still showed the wild-type dppIV hybridization signals, but additional hybridizing fragments suggested heterologous integration of the disruption construct. This result indicates that all detectable prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase secreted by A. oryzae TK3 on MMWGH is encoded by the dppIV gene.

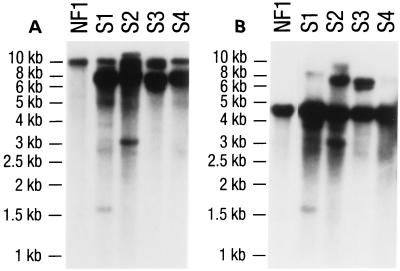

FIG. 4.

Southern blot analysis of A. oryzae dppIV disruptants. NcoI-digested genomic DNA from four pNFF129 transformants without prolyl dipeptidase activity (D1 to D4) and two transformants retaining enzyme activity (D5 and D6) were hybridized under high-stringency conditions with a PCR fragment encoding the whole DPPIV as a probe. A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ (NF1) DNA was used for comparison.

Overexpression of the dppIV gene.

Plasmid pNFF125 containing the cloned 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV fragment was introduced into A. oryzae NF1 by cotransformation with plasmid pNFF28 carrying the A. oryzae pyrG gene as the selection marker. Transformants were selected on MM. Ninety-five pyrG+ transformants were incubated on MMWGH for 2 days at 30°C before screening for secreted DPPIV activity was performed. Sixteen transformants clearly exhibited increased staining compared to that of the wild type (Fig. 3B). In liquid MMWG medium, the maximum activity of DPPIV obtained in A. oryzae DPPIV-overexpressing transformants was 17 times higher than that of the A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ control strain. Four transformants, designated S1 to S4, were selected because of their elevated DPPIV activity.

EcoRV and ApaI-EcoRV-digested genomic DNA were analyzed by Southern blotting (Fig. 5) onto nylon membranes and hybridized under high-stringency conditions with a dppIV probe obtained by standard PCR using primers 3260 and 3261 (Table 1). The 10-kb EcoRV fragment (Fig. 5A) carrying the whole resident dppIV gene was used as a single-copy gene reference. The 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV band (Fig. 5B) was regarded as consisting of integrated dppIV fragments from plasmid pNFF125 in addition to the resident dppIV gene. Comparison of the intensity of the 10-kb EcoRV band to that of the 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV band suggests the presence of multiple copies of the dppIV gene in the transformants overexpressing DPPIV activity. In parallel, 10 nonoverexpressing transformants were analyzed. The ApaI-EcoRV 4.8-kb fragment signal did not show a higher intensity than the 10-kb EcoRV fragment (data not shown), indicating that pNFF125 was not integrated. Southern blot analysis supported the idea that increased activity was due to multiple copies of the 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV fragment being integrated into the genome of the transformants.

FIG. 5.

Southern analysis of four prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase-overproducing transformants (S1 to S4). A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ DNA was used for comparison. EcoRV (A)- and ApaI-EcoRV (B)-digested genomic DNAs, hybridized under high-stringency conditions with a PCR fragment encoding the whole DPPIV as a probe, are shown.

The numbers of the dppIV gene copies in transformants S1 to S4 were estimated by densitometric scan of the Southern blot to be 12, 3, 4, and 9, respectively. The DPPIV activities of these same transformants were determined to be 10, 3, 8, and 17 times higher than the activity of A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ control strain after growth for 7 days at 30°C in 100 ml of liquid MMWG without shaking. These data confirm that an increase in the number of gene copies results in a higher production level but without linear correlation. This could be due to the fact that, besides the number of gene copies, the site of integration also may affect the expression of the introduced genes (52).

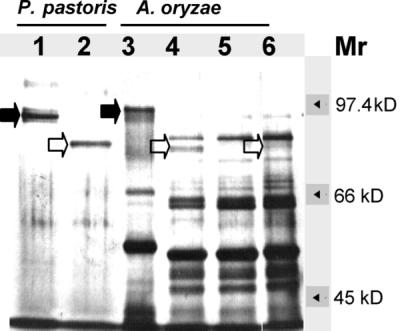

Identification of DPPIV protein in culture medium.

Culture broth from the prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase-overproducing transformant S4 and from A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ as a control strain were analyzed by SDS-PAGE to identify the DPPIV protein. A broad smear was visible in the region of 95 kDa for the prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase-overproducing strain (Fig. 6, lane 3) but not in the A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+ control (data not shown), suggesting that the DPPIV protein was glycosylated. After the samples were treated with N-glycosidase F, a band of about 85 kDa appeared in the NF1 pyrG+ control as well as in the prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase-overproducing transformant (Fig. 6, lanes 4 and 6) but not in the dppIV disruptant culture broth (Fig. 6, lane 5). The amount of deglycosylated DPPIV obtained from the overexpressing transformant culture broth was substantial enough to determine the initial amino acid residues of the N terminus of the protein by in situ automated Edman degradation. The N-terminal sequence of the mature protein was determined to be Leu-Asp-Val-Pro-Arg-, indicating that DPPIV was the major protein species in the excised band.

FIG. 6.

Silver staining of an SDS–7.5% polyacrylamide gel to detect glycosylated and deglycosylated proteins in culture broths of P. pastoris and A. oryzae transformants. Lane 1, untreated DPPIV from P. pastoris; lane 2, N-deglycosylated DPPIV from P. pastoris; lane 3, untreated culture broth of transformant S4; lane 4, N-deglycosylated culture broth of transformant S4; lane 5, N-deglycosylated culture broth of disruptant D1; lane 6, N-deglycosylated sample from A. oryzae NF1 pyrG+. Solid arrows indicate recombinant and native glycosylated A. oryzae DPPIV enzymes. Open arrows indicate N-deglycosylated DPPIV. Mr, molecular size.

Expression of A. oryzae DPPIV in P. pastoris.

P. pastoris transformants secreted A. oryzae DPPIV enzyme in the BMMY medium at the maximal rate of 100 μg/ml (8,000 mU/ml) after 48 h of expression. This rate is about 800 times that of A. oryzae TK3 in liquid MMWG (10 mU of DPPIV/ml). Under identical culture conditions, P. pastoris GS115 did not secrete any DPPIV (data not shown). Recombinant DPPIV was active between pH 4.0 and 9.0, with optimal activity at pH 7.0 (data not shown), and had a specific activity of 100 mU/μg when Ala-Pro-p-nitroanilide was used as a substrate.

SDS-PAGE analysis showed that the secreted, recombinant A. oryzae DPPIV was the major protein present in the culture medium of P. pastoris. This protein migrated as a slightly smearing band between 95 and 100 kDa (Fig. 6, lane 1). However, upon treatment with N-glycosidase F, this broad band gave rise to a sharp band at 85 kDa (Fig. 6, lane 2), similar to the one obtained after deglycosylation of the DPPIV secreted by A. oryzae dppIV cotransformants (Fig. 6, lane 4).

Role of DPPIV activity in WG hydrolysis.

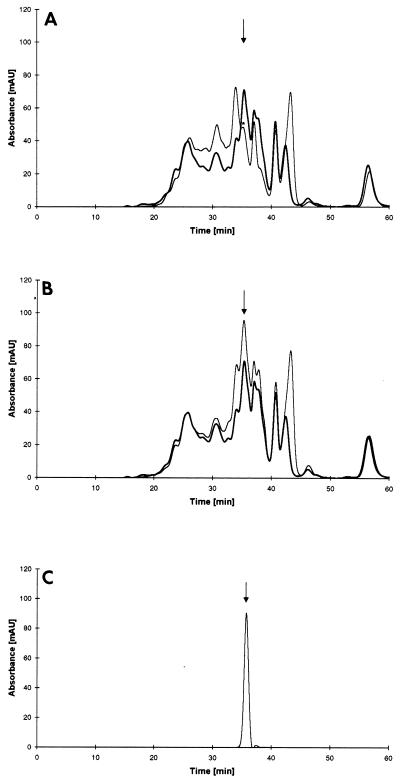

To test the function of DPPIV in WG hydrolysis, we compared the peptide profiles of hydrolysates from WG-containing medium after inoculation with both the DPPIV disruptant D1 and the wild-type TK3 strain (Fig. 7A). By size exclusion chromatography analysis, the Ala-Pro dipeptide control eluted after 35 min (Fig. 7C). In the culture broth of wild-type strain TK3, a large peak of dipeptides was obtained. However, the lack of DPPIV activity in the D1 strain gave only a residual peak, which perhaps resulted from the action of another dipeptidyl peptidase homologous to that characterized in A. fumigatus (3). The level of larger peptides (elution time, 25 to 35 min) was higher in the disruptant culture broth than in that of the wild-type strain. However, when purified DPPIV produced in P. pastoris was added to the disruptant culture broth at the level of wild-type activity and incubated for 24 h, the pattern of the peptide profile was similar to that of the wild type (Fig. 7B), thus confirming the role of this enzyme in peptide degradation.

FIG. 7.

(A and B) Peptide profiles obtained through hydrolysis of WG by A. oryzae TK3 (bold line) and disruptant D1 (thin line). In panel B, 320 mU of purified DPPIV produced in P. pastoris was added to 500 μl of disruptant D1 culture medium. (C) Elution profile of dipeptide Ala-Pro used as a control. The peaks corresponding to dipeptide elution are indicated by arrows. An asterisk indicates a residual peak possibly due to peptide hydrolysis by another dipeptidyl peptidase.

DISCUSSION

Several facts support the conclusion that we have successively cloned the gene encoding the prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase and that this gene is responsible for the enzyme activity detected in A. oryzae culture broth. (i) Disruption of the dppIV gene abolished all detectable prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity. (ii) Prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity increased upon introduction of multiple copies of the 4.8-kb ApaI-EcoRV fragment, which encompasses the dppIV gene, into A. oryzae. (iii) Insertion of the dppIV coding region into the P. pastoris expression system led to high-level secretion of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase. Under identical culture conditions, wild-type P. pastoris does not produce any prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity.

As secreted protein, A. oryzae DPPIV is synthesized as a preprotein precursor. The N-terminal sequence of the mature protein, determined to be Leu-Asp-Val-Pro-Arg-, is preceded by a 16-amino-acid (16-aa) signal peptide with a hydrophobic core of 9 aa and a putative signal peptidase cleavage site in accordance with the −3,−1 von Heijne’s rule (54). The DPPIV protein molecules generated after signal peptidase cleavage are 755 aa long. The polypeptidic chain of the mature protein has a calculated molecular mass of 85.5 kDa, which is in accordance with that estimated for the deglycosylated protein by SDS-PAGE. The amino acid sequence of A. oryzae DPPIV contains six potential N-linked glycosylation (Asn-X-Thr) sites which are conserved in A. fumigatus DPPIV, and the secreted enzyme contains approximately 10 kDa of N-linked carbohydrate (Fig. 6).

A. oryzae DPPIV is closely related to A. fumigatus DPPIV. These enzymes are homologous to human CD26 (11), Saccharomyces cerevisiae DPAP B (42), Xanthomonas maltophilia DP IV (17) and Flavobacterium meningosepticum DP IV (16), with around 35% identity, based on the algorithm of Needleman and Wunsch (36). The greatest homology is seen at the 200 aa of the C termini of the proteins. In this area, we find the Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly consensus sequence for the catalytic site of serine proteases (8). In the A. oryzae DPPIV amino acid sequence, the Ser 618 residue in the Gly-X-Ser-X-Gly consensus sequence forms, with Asp 695 and His 730, which are conserved in the previously cited prolyldipeptidyl peptidases, a catalytic triad described for serine proteases and lipases (7). However, unlike the Aspergillus DPPIVs, which are secreted proteins, the human, rat (38), yeast, F. meningosepticum, and X. maltophilia prolyl dipeptidyl peptidases are membrane-bound proteins and contain an N-terminal noncleavable signal sequence which serves as a membrane anchor. By contrast, the deduced amino acid sequences of DPPIVs from Lactococcus lactis (X-PDAP) (21, 35), Lactobacillus delbrueckii (PepX) (22), and Lactobacillus helveticus (PepX) (53) are located intracellularly (18) and do not exhibit significant sequence similarity with the aforementioned DPPIVs (data not shown).

The dppIV null mutants did not exhibit any detectable change in phenotype other than the absence of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity, suggesting that this activity is not essential for viability, which is consistent with the absence of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity in wild-type A. niger strains. However, the loss of prolyl dipeptidyl peptidase activity in the dppIV null mutant grown on liquid MMWG led to a diminution in the number of dipeptides released and a simultaneous accumulation of larger peptides. These effects were reversed by the addition of purified recombinant DPPIV. Our results suggest an important role for this enzyme in koji fermentation processes, especially when a WG-based substrate rich in Pro residues is used. It is likely that another dipeptidyl peptidase is also involved during hydrolysis of WG. The residual peak observed in the culture broth of the A. oryzae disruptant may be due to an alanyl dipeptidyl peptidase that is present in A. oryzae (data not shown) and homologous to the DPPV enzyme of A. fumigatus. The role of this group of enzymes in koji fermentation is currently being investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Patricia Vautravers, Katrin Macé, and Karin Gartenmann for technical assistance and Andrea Pfeiffer, Peter Niederberger, and Anne Donnet for critically reading the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler-Nissen J, editor. Enzymatic hydrolysis of food proteins. London: Elsevier Applied Sciences Publishers Ltd.; 1986. Methods in food protein hydrolysis; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aratake Y, Kotani T, Tamura K, Araki Y, Kuribayashi T, Konoe K, Ohtaki S. Dipeptidyl aminopeptidase IV staining of cytologic preparations to distinguish benign from malignant thyroid disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:306–310. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/96.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beauvais A, Monod M, Debeaupuis J P, Diaquin M, Kobayashi H, Latgé J P. Biochemical and antigenic characterization of a new dipeptidyl-peptidase isolated from Aspergillus fumigatus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6238–6244. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauvais A, Monod M, Wyniger J, Debeaupuis J P, Grouzmann E, Brakch N, Svab J, Hovanessian A G, Latgé J P. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV secreted by Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungus pathogenic to humans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3042–3047. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3042-3047.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berka R M, Carmona C L, Hayenga K J, Thompson S A, Ward M. Isolation and characterization of the Aspergillus oryzae gene encoding aspergillopepsin O. Gene. 1993;125:195–198. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90328-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borg-von Zepelin M, Beggah S, Boggian K, Sanglard D, Monod M. The expression of the secreted aspartyl proteinases Sap4 to Sap6 from Candida albicans in murine macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:543–554. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brady L, Brzozowski A M, Derewenda Z S, Dodson E, Dodson G, Tolley S, Turkenburg J P, Christiansen L, Huge-Jensen B, Norskov L, Thim L, Menge U. A serine protease triad forms the catalytic centre of a triacylglycerol lipase. Nature. 1990;343:767–770. doi: 10.1038/343767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brenner S. The molecular evolution of genes and proteins: a tale of two serines. Nature. 1988;334:528–530. doi: 10.1038/334528a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chambers S P, Prior S E, Barstow D A, Minton N P. The pMTL nic− cloning vectors. I. Improved pUC polylinker regions to facilitate the use of sonicated DNA for nucleotide sequencing. Gene. 1988;68:139–149. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90606-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheevadhanarak S, Renno D V, Saunders G, Holt G. Cloning and selective overexpression of an alkaline protease-encoding gene from Aspergillus oryzae. Gene. 1991;108:151–155. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90501-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Darmoul D, Lacasa M, Baricault L, Marguet D, Sapin C, Trotot P, Barbat A, Trugnan G. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (CD26) gene expression in enterocyte-like colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4824–4833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Ruiter-Jacobs Y M J T, Broekhuijsen M, Unkles S E, Campbell E I, Kinghorn J R, Contreras R, Pouwels P H, van den Hondel C A M J J. A gene transfer system based on the homologous pyrG gene and efficient expression of bacterial genes in Aspergillus oryzae. Curr Genet. 1989;16:159–163. doi: 10.1007/BF00391472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukushima D. Fermented vegetable protein and related foods of Japan and China. Food Rev Int. 1985;1:149–209. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grossberger D. Minipreps of DNA from bacteriophage lambda. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:6737. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.16.6737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabashima T, Yoshida T, Ito K, Yoshimoto T. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of the dipeptidyl peptidase IV gene from Flavobacterium meningosepticum in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;320:123–128. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kabashima T, Ito K, Yoshimoto T. Dipeptidyl-peptidase IV from Xanthomonas maltophilia: sequencing and expression of the enzyme gene and characterization of the expressed enzyme. J Biochem. 1996;120:1111–1117. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunji E R S, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings W N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lerner C G, Inouye M. Low copy number plasmids for regulated low-level expression of cloned genes in Escherichia coli with blue/white insert screening capability. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4631. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lojda Z. Studies on glycyl proline naphthylamidase. I. Lymphocytes. Histochemistry. 1977;54:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00508273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayo B, Kok J, Venema K, Bockelmann W, Teuber M, Reinke H, Venema G. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:38–44. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.38-44.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer-Barton E C, Klein J R, Iman M, Plapp R. Cloning and sequence analysis of the X-prolyl-dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase gene (pepX) from Lactobacillus delbrückii subsp. lactis DSM7290. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;40:82–89. doi: 10.1007/BF00170433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monod M. Construction of a genomic library for A. fumigatus. In: Maresca B, Kobayashi G S, editors. Molecular biology of pathogenic fungi: a laboratory manual. New York, N.Y: Telos Press; 1994. pp. 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagakawa Y. Alkaline proteinases from Aspergillus. Methods Enzymol. 1970;19:581–591. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of acid carboxypeptidase I from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1972;36:1343–1352. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of acid carboxypeptidase II from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1972;36:1473–1480. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of acid carboxypeptidase III from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1972;36:1481–1488. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of neutral proteinase I from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:2695–2701. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of neutral proteinase II from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:2703–2708. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of alkaline proteinase from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:2685–2694. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of leucine aminopeptidase I from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:757–765. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of leucine aminopeptidase II from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:767–774. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of leucine aminopeptidase III in Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:775–782. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakadai T, Nasuno S, Iguchi N. Purification and properties of acid carboxypeptidase IV from Aspergillus oryzae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:1237–1251. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nardi M, Chopin M C, Chopin A, Cals M M, Gripon J C. Cloning and DNA sequence analysis of an X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase gene from Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis NCDO 763. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:45–50. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.45-50.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Needleman S B, Wunsch C D. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequences of two proteins. J Mol Biol. 1970;48:443–453. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oakley B R, Rinehart J E, Mitchell B L, Oakley C E, Carmona C L, Gray G L, May G S. Cloning, mapping and molecular analysis of the pyrG (orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase) gene of Aspergillus nidulans. Gene. 1987;61:385–399. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ogata S, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y. Primary structure of rat liver dipeptidyl peptidase IV deduced from its cDNA and identification of the NH2-terminal signal sequence as the membrane-anchoring domain. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:3596–3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ozawa Y, Suzuki K, Mizunuma T, Mogi K. An aminopeptidase of Aspergillus sojae. Agric Biol Chem. 1973;37:1285–1293. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pontecorvo G, Roper J A, Hemmons L M, McDonald K D, Bufton A W J. The genetics of Aspergillus nidulans. Adv Genet. 1953;5:141–239. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raeder U, Broda P. Rapid preparation of DNA from filamentous fungi. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1985;1:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roberts C J, Pohlig G, Rothman J H, Stevens T H. Structure, biosynthesis, and localisation of dipeptidyl aminopeptidase B, an integral membrane glycoprotein of the yeast vacuole. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1363–1373. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.4.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulsen A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarath G, De La Motte R, Wagner F W. Protease assay methods. In: Beynon R J, Bond J S, editors. Proteolytic enzymes: a practical approach. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1989. pp. 25–55. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tachi H, Ito H, Ichishima E. An X-prolyl dipeptidyl-aminopeptidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Phytochemistry. 1992;31:3707–3709. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tatsumi H, Ogawa Y, Murakami S, Ishida Y, Murakami K, Masaki A, Kawabe H, Arimura H, Nakano E, Motai H. A full length cDNA clone for the alkaline protease from Aspergillus oryzae: structural analysis and expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:33–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00261154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tatsumi H, Murakami S, Tsuji R F, Ishida Y, Murakami K, Masaki A, Kawabe H, Arimura H, Nakano E, Motai H. Cloning and expression in yeast of a cDNA clone encoding Aspergillus oryzae neutral protease II, a unique metalloprotease. Mol Gen Genet. 1991;228:97–103. doi: 10.1007/BF00282453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsujita Y, Endo A. Purification and characterization of the two molecular forms of Aspergillus oryzae acid protease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1976;445:194–204. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(76)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tsujita Y, Endo A. Chemical properties of the polysaccharides associated with acid protease of Aspergillus oryzae grown on solid bran media. J Biochem. 1977;81:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a131529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Van den Broek, P. Unpublished results.

- 52.Verdoes J C, Punt P J, van den Hondel C A M J J. Molecular genetic strain improvement for the overproduction of fungal proteins by filamentous fungi. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1995;43:195–205. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vesanto E, Savijoki K, Rantanen T, Steele J L, Palva A. An X-prolyl dipeptidyl aminopeptidase (pepX) gene from Lactobacillus helveticus. Microbiology. 1995;141:3067–3075. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]