Abstract

Background

Spastic paraplegia type 7 (SPG7) mutations can present either as a pure form or a complex phenotype with movement disorders.

Objective

Describe the main features of subjects with SPG7 mutations associated with movement disorders.

Methods

We analyzed the clinical and paraclinical information of subjects with SPG7 mutations associated with movement disorders.

Results

Sixteen affected subjects from 11 families were identified. Male sex predominated (10 of 16) and the mean age at onset was 41.25 ± 16.1 years. A cerebellar syndrome was the most frequent clinical movement disorder phenotype (7 of 16); however, parkinsonism (2 of 16), dystonia (1 of 16), and mixed phenotypes between them were also seen. The “ears of the lynx” sign was found in four subjects. A total of nine SPG7 variants were found, of which the most frequent was the c.1529C > T (p.Ala510Val).

Conclusion

This case series expands the motor phenotype associated with SPG7 mutations. Clinicians must consider this entity in single or familial cases with combined movement disorders.

Keywords: spastic paraplegia type 7, movement disorders, parkinsonism, dystonia, tremor, ataxia

The hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) comprise a large and heterogeneous group of inherited neurologic disorders, with a defining and unifying feature of prominent lower extremity spasticity. Complex forms are associated with additional, often prominent, features including more severe neuropathy, seizures, parkinsonism, cognitive impairment, amyotrophy, short stature, and visual abnormalities, among others. A recent interesting finding in this field is the multiple modes of inheritance reported for variants of several causal genes. 1 Pathogenic variants in the spastic paraplegia gene 7 (SPG7) account for approximately 5%–21% of autosomal recessive HSPs cases. However, several reports have proposed possible dominant inheritance for some variants of this gene. 2 , 3

In large SPG7 cohorts most of the cases show pure phenotypes with only a small proportion of them exhibiting complex forms of the disease, combining spasticity with ataxia and parkinsonism as the main movement disorders. 4 , 5 Recently, new complex phenotypes have been described. The aim of this report is to describe the clinical and paraclinical features of patients with SPG7 mutations associated with movement disorders.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed medical records of subjects who presented to four different movement disorders clinics in Canada, Portugal, Mexico, and Germany. Cases with SPG7 variants manifesting movement disorders were included. Clinical and paraclinical information, including demographic data, clinical assessment, imaging findings, genetic analysis, and additional available studies were analyzed.

Because the design of the study was retrospective, a full ethics review was not required. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Results

Sixteen subjects from twelve families native of Canada (n = 6), Portugal (n = 5), Mexico (n = 4) and Germany (n = 1) were included in the study (Table 1). Male sex predominated (10 of 16); mean age was of 56.5 ± 15.9 years (median, 59 years; range, 16–79 years) and mean age of onset was 41.25 ± 16.1 years (median, 40 years; range, 5–72 years). Overall, most of the subjects had gait and balance problems (11 of 16) as the presenting feature, followed by a combination of speech and balance abnormalities (2 of 16), dystonia (2 of 16), and parkinsonism (1 of 16).

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of cases with SPG7 pathogenic variants

| Subject | Country | Sex | Age, y | Age at onset, y | Initial features | MD phenotype | Clinical features | Family background | MRI findings | SPG7 variant | Genotype status | Pathogenicity | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mexico | M | 64 | 49 | Balance and gait problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Skew deviation, hyperreflexia in lower limbs | Sibling of case 2 | Ears of the lynx sign, cerebellar atrophy, bilateral parietal atrophy | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) | Homozygous | Pathogenic | Single nucleotide |

| 2 | Mexico | M | 54 | 35 | Gait and balance problems | MSA‐C‐like | Skew deviation, multidirectional gaze limitation, spastic paraparesis, erectile dysfunction, incontinence | Sibling of case 1 | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) | Homozygous | Pathogenic | Single nucleotide |

| 3 | Portugal | F | 43 | 36 | Gait and balance problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Square wave jerks, spastic paraparesis, lower limb hypestesia, cerebellar ataxia, pes cavus | Consanguinity among parents and paternal grandparents; daughter of case 4 | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1454_1462del p.(Arg485_Glu487del) | Homozygous | Pathogenic | Deletion |

| 4 | Portugal | M | 69 | 40 | Gait and balance problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Square wave jerks, spastic paraparesis, neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia | Consanguinity among parents; father of case 3 | NA | c.1454_1462del p.(Arg485_Glu487del) | Homozygous | Pathogenic | Deletion |

| 5 | Canada | M | 64 | 32 | Spasmodic dysphonia and writers' cramp | Dystonia‐ataxia | Upgaze limitation, spasmodic dysphonia, writer's cramp, action tremor, spastic paraparesis, cerebellar ataxia, urinary urgency | Sibling of case 6 and 7 | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) and c.2096dupT p.(Met699fs) | Compound heterozygous | Pathogernic | Duplication |

| 6 | Canada | M | 55 | 40 | Slurred speech and gait problems | Dystonia‐ataxia | Upgaze limitation, postural/intention tremor, foot dystonia, spastic paraparesis, cerebellar ataxia | Sibling of case 5 and 7 | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) and c.2096dupT p.(Met699fs) | Compound heterozygous | Pathogenic | Duplication |

| 7 | Canada | F | 57 | 37 | Balance and gait problems. | Parkinsonism‐ dystonia‐ataxia | Multidirectional diplopia, upgaze limitation, spastic paraparesis, foot dystonia, action and rest tremor, freezing, cerebellar ataxia. Responsiveness to L‐dopa, epilepsy | Sibling of case 5 and 6 | Ears of the lynx sign | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) and c.2096dupT p.(Met699fs) | Compound heterozygous | Pathogenic | Duplication |

| 8 | Portugal | F | 58 | 52 | Gait problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Spastic tetraparesis, cerebellar ataxia, pes cavus, subcutaneous nodules at hips | None | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1529C > T p.(Ala510Val) and c.184‐?_376 +?del(p.?) | Compound heterozygous | Pathogenic | Single nucleotide/deletion |

| 9 | Germany | F | 63 | 40 | Gait and balance problems | Cerebellar syndrome | External ophthalmoplegia, spasticity, neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia | Gait and balance problems in her mother | Cerebellar atrophy | c.1045G > A; p.(Gly349Ser) and c.1454_1462del; p.(Arg485_Glu487del) | Compound heterozygous | Pathogenic | Single nucleotide/9 bp deletion |

| 10 | Mexico | M | 16 | 5 | Right leg dystonia | Generalized dystonia | Dysarthria, anxiety, nocturnal cramps | None | Ears of the lynx sign | c.1468G > T, p.(Glu490Ter) | Heterozygous | Likely pathogenic | Nonsense |

| 11 | Mexico | F | 29 | 25 | Clumsiness micrographia tremor | Dystonia‐parkinsonism | Cervical dystonia and parkinsonism. Responsiveness to dopaminergic therapy (pramipexole and rasagiline) | Maternal grandfather with parkinsonism | Ears of the Lynx sign | c.1468G > T, p.(Glu490Ter) | Heterozygous | Likely pathogenic | Nonsense |

| 12 | Canada | M | 65 | 30 | Gait problems | Parkinsonism | Spastic paraparesis, urinary urgency | Gait disturbance in mother, 3 siblings and 1 child. One sibling had a diagnosis of Lewy Body Dementia | None | c.1053dupC p.(Gly352fs) | Heterozygous | Pathogenic | 1 bp duplication |

| 13 | Canada | F | 74 | 72 | Gait problems, jaw tremor, micrographia | Parkinsonism | Mild external ophthalmoplegia with ptosis, jaw tremor, mild cerebellar symptoms, RBD, constipation, hyposmia, anxiety. Responsiveness to L‐dopa, motor and non‐motor fluctuations | None | Mild cerebellar atrophy | c.861dup p.(Asn288) | Heterozygous | Pathogenic | 1 bp duplication |

| 14 | Portugal | M | 60 | 50 | Gait problems | Dystonia‐ataxia | Dementia, cervical and truncal dystonia, spastic tetraparesis, neuropathy, cerebellar ataxia | None | Cortical global atrophy | c.‐9C > T‐5'UTR | Heterozygous | Pathogenic | Single nucleotid |

| 15 | Portugal | M | 54 | 48 | Speech and gait problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Cerebellar ataxia, right pyramidal syndrome | None | Cerebellar atrophy | c.397C > T p.(Arg133Trp) | Heterozygous | Pathogenic | SNV single nucleotide variation/missense variant |

| 16 | Canada | M | 79 | 69 | Balance and gait problems | Cerebellar syndrome | Cerebellar ataxia | Father with AD, 2 siblings with memory problems | Cerebellar atrophy (vermis). Amyloid angiopathy, periventricular white matter changes | c. 1450‐446_1779 + 746 delinsAAAGTGCT | Heterozygous | Pathogenic | Deletion |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; MD, movement disorder; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder; SPG7, spastic paraplegia type 7.

A cerebellar syndrome (lower limb predominant) was the most frequent movement disorder phenotype, present in seven subjects, followed by a mixed phenotype of dystonia‐ataxia in three subjects, parkinsonism in two, dystonia‐parkinsonism in one, and a combination of parkinsonism‐dystonia‐ataxia in one. Finally, one subject developed a multiple system atrophy type C (MSA‐C) phenotype, while another showed an isolated dystonia as the main clinical feature. Among those with coexistent parkinsonism, improvement in their symptoms with dopaminergic therapy was observed, and one of them developed motor fluctuations from levodopa therapy.

Upper motor neuron signs were found in 11 subjects, spastic paraparesis was the most common form of presentation, seen in six individuals. There were two cases in which spastic tetraparesis were found. Two subjects had signs of sensory neuropathy, whereas another showed a sensorimotor axonal neuropathy on electrophysiological studies.

Ocular movement abnormalities were found in 10 subjects; up gaze limitation was the most common finding, followed by ophthalmoparesis/ophthalmoplegia (one of these subjects had also ptosis), skew deviation, and square wave jerks. None of them had optic atrophy.

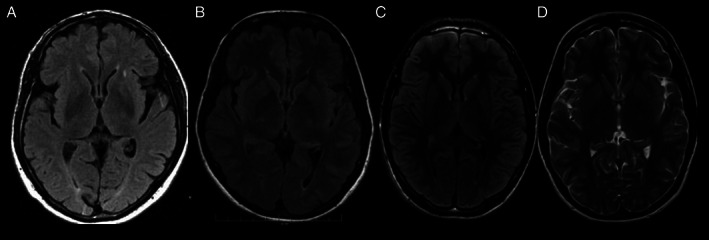

Imaging studies were available in 15 subjects, with global cortical cerebellar atrophy being the most frequent finding in 10 of them. Interestingly four subjects revealed hyperintensities in the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles (“ears of the lynx” sign) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Axial MRI from subjects 1 (A), 7 (B), 10 (C) and 11 (D) showing frontal horn hyperintensities at FLAIR and T2 sequences, consistent with “ears of the lynx” sign.

We found a total of 11 different SPG7 variants; whole exome sequencing was used in all patients. Seven cases were heterozygous, compound heterozygous in five and homozygous in four. The c.1529C > T (p.Ala510Val) genetic variant was the most frequent finding, present either as homozygous, heterozygous, or compound heterozygous state.

Main clinical features from these subjects are shown in the (Video 1).

Video 1.

Main clinical features from 16 cases with movement disorders associated to SPG7 pathogenic variants.

Discussion

SPG7 is typically an autosomal recessive pure or complicated HSP resulting from homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in the SPG7 gene. A dominant/heterozygous mode of inheritance has also rarely been reported, 4 however, a recent report challenged this notion finding that one such patient with ataxia and spastic paraplegia carried a second deep intronic variant only identified by whole‐genome sequencing. 6 Although this disease is associated with mutations in the SPG7 gene, the distribution of expression of this gene in different tissues suggests that other mutations of SPG7 may exist that are associated with different phenotypes. 7

In addition to spastic paraplegia, large cohorts of SPG7 subjects have shown complex phenotypes. However, additional movement disorders such as cervical dystonia, myoclonus, and parkinsonism have also been reported. 4 , 5 More recently, single cases of spasmodic dysphonia, 8 limb dystonia, 9 palatal tremor, 10 and two cases of MSA‐C like 11 , 12 have widened the spectrum with most of these new cases, showing little or no spasticity (Table 2). Large cohorts have also included cases without any sign of spastic paraplegia. 4

TABLE 2.

Uncommon movement disorders associated with SPG7 pathogenic variants

| Author | Age at onset, y | Sex | Clinical features | MRI | SPG7 variant | Genotype status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hall et al 8 | 17 | M | Spasmodic dysphonia, spasticity, dysphagia | Normal | c.233 T4A (p.Leu78X) | Homozygous |

| Schaefer et al 9 | 40 | M | Limb dystonia, cerebellar ataxia, mild spasticity | Normal |

c.2096dupT, p.(Met699Ilefs*4) c.1529C > T (p.Ala510Val) |

Compound heterozygous |

| van Gassen et al 5 | 16 | F | Cervical dystonia, spasticity | NA | c.2115‐2131del (p.Leu706fs) | Homozygous |

| 48 | F | Cervical dystonia, spasticity | NA |

c.861dup, p.Asn288X c.2228 T > C (p.Ile743Thr) |

Compound heterozygous | |

| De la Casa‐Fages et al 4 | 30 | M | Myoclonus, head dystonia, tremor | Cerebellar and cortical atrophy | c.1529C > T, p.(Ala510Val) | Homozygous |

| 50 | M | Pisa Syndrome, parkinsonism | Cortical atrophy | c.1529C > T, p.(Ala510Val) | Homozygous | |

| Gass et al 10 | 41 | M | Palatal tremor, macrocephaly, cognitive decline, lower limb weakness/spasticity | Mild cerebellar atrophy |

p.Ala510Val (c.1529C > T) p.Arg485_Glu487del (c.1454_1462del) |

Compound heterozygous |

| Campins‐Romeu et al 16 | 17 | M | Multifocal dystonia with prominent bulbar and cervical involvement | Mild cerebellar atrophy and T2‐weighted hyperintensities of the cerebral peduncles | c.1529C > T(p.Ala510Val) and c.1715C > T(p.Ala572Val) | Homozygous |

| Coarelli et al 17 | NA | NA | Dystonia | NA | NA | NA |

| NA | NA | Parkinsonism | NA | NA | NA |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not available; SPG7, spastic paraplegia type 7.

Cerebellar ataxia is a common finding in SPG7 variants. 13 The combination of cerebellar ataxia and autonomic features (MSA‐C‐like phenotype), as shown in case 2, seems to be even more unusual. Beyond ataxia, parkinsonism is the most common movement disorder described in SPG7 pathogenic variants and has been reported to be present in 21% of SPG7 subjects. 4 In case 11, parkinsonism and dystonia had a remarkable response to the combination of pramipexol and rasagiline.

With respect to dystonia, focal type (cervical) has been one of the most frequent findings in large SPG7 cohorts. 5 However, generalized forms, as shown in case 10 have not been previously reported. The latter started at the age of 5 years with dystonia in the lower extremities that generalized by the time he was 7 years old, dystonic features were not responsive to levodopa. Moreover, case 5 had both spasmodic dysphonia and writer's cramp, which have been described separately in single case reports. 8 , 9

Multiple radiologic findings can be seen, including cerebellar and brain atrophy, 4 , 5 as shown in some of our cases. The “ears of the lynx” sign, consisting in T2 and fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintensities at the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles, have been commonly described among SPG11 and SPG15 cases; however, some SPG7 cases can also present this magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) sign. 13

Functional imaging of cases with dopa‐responsive parkinsonism associated with SPG7 mutations have demonstrated bilateral nigrostriatal presynaptic dopaminergic denervation, which provides clear evidence that SPG7 subjects have a more widespread brain involvement besides the pyramidal tracts. 4 , 14

Although a clear mechanism by which SPG7 pathogenic variants could cause disease is uncertain, evidence indicates that SPG7 mutations induce mitochondrial biogenesis, possibly causing the clinical abnormalities commonly found among these subjects. The mechanisms involved are upregulation of mitochondrial gene expression, protein synthesis, and increased mitochondrial mass, which are typical for a mitochondrial disorder. In accordance with this, progressive external ophthalmoplegia and ptosis fall within the spectrum of complex SPG7 phenotypes, which are classical presenting features of mitochondrial disease. 15

The wide spectra of age at onset, progression, and symptoms, together with the clinical overlap with other neurological diseases and the high degree of genetic heterogeneity, has made it difficult to establish phenotype–genotype correlations in large cohorts carrying SPG7 variants. 1 However, in our case series, two unrelated subjects with dystonia (cases 10 and 11) had the same SPG7 heterozygous likely pathogenic variant (c.1468G > T, p.Glu490Ter). The related cases 1 and 2 showed the most frequent variant encountered in SPG7 cases, the homozygous variant (c.1529C > T p.[Ala510Val]) 4 , 5 and more often associated with ataxia than with spastic paraplegia, 1 nevertheless one of these cases showed both clinical features, perhaps associated with a longstanding disease. Case 12 showed a heterozygous pathogenic variant (c.1053dupC [p.Gly352fs]) that has been reported in compound heterozygous state in individuals with HSP 5 and cases 5–9 carried the same compound heterozygous variants that were reported in three quarters of all patients in a large case series. 4

Although heterozygous variants had been previously described among SPG7 cases, some of these could manifest disease throughout different genetic mechanisms, mainly those manifesting parkinsonism as a core feature. Whole exome sequencing (WES) and panels designed for parkinsonism, dystonia, and other neurodegenerative diseases were sought in most of our heterozygous cases, but additional information was not obtained from them. However, we cannot confirm at this point if the aforementioned heterozygous variants are completely responsible for the phenotype found among those subjects. Further, we did not perform WES, so we cannot exclude the possibility of an additional deep intronic variant as reported recently. 6 In addition to the intronic variants, another possibly implicated mechanism in our heterozygous SPG7 variants is digenic inheritance (carrying two mutations in different HSP genes). Recently, in a large Canadian SPG7 cohort, 6.5% carried biallelic SPG7 variants. We found that the number of pathogenic/likely pathogenic SPG7 alleles in HSP cases is higher than in controls, suggesting potential dominant or digenic inheritance in some. 3

Regarding clinical features, comparing between heterozygous and biallelic variant carriers, some differences have been found. As in a recently published SPG7 case series, 16 our compound heterozygous subjects (and even those with heterozygous variants) showed more complex phenotypes including dystonia, parkinsonism, tremor, and external ophthalmoplegia, than those with homozygous variants, which showed mainly cerebellar syndromes. However, there are also single SPG7 cases with movement disorders reported in the literature, in a homozygous state (Table 2).

In accordance with this, a study of 585 HSP subjects from 372 families and 1175 controls, upper extremity ataxia (37.9%) and intent tremor (30%) were relatively common in biallelic carriers of SPG7 variants, but none of the heterozygous carriers showed these symptoms. On the other side, subjects with heterozygous SPG7 variants had younger age at onset compared to those with biallelic variants (16.5 vs. 33.8 years; P = 0.021). 3

Finally, single heterozygous SPG7 mutations have also been identified in cases with chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia, ataxia and lower limb spasticity. 15

This case series widens the spectrum of SPG7 mutations. Clinicians must consider SPG7 mutations as a possible etiology in movement disorders of unknown origin or in single or familial cases with combined movement disorders, and alternatively, clinicians must look for movement disorders in this entity, because these clinical features could have been previously underreported.

Author Roles

(1) Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution; (2) Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and Critique; (3) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft, B. Review and Critique.

M.S.F.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 3A

A.E.L.: 1A, 2B, 2C, 2C, 3A 3B

L.K.: 1B, 1C, 3A

I.C.:1B, 1C, 3A

M.S.: 1B, 1C, 3A

G.K.: 1B, 1C, 3A

C.G.: 1B, 1C, 3A

R.M.: 1A, 3A, 3B

A.F.:1A, 2C, 3A 3B

C.E.P.A.: 3B

C.Z.R.: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A, 3B

Disclosures

Ethical Compliance Statement: We confirm that we have read the Journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines. This study was approved by the local Ethics Committee from each hospital. Patients have signed consent for video acquisition and publication.

Funding Sources and Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no funding sources or conflicts of interest.

Financial Disclosures for the Previous 12 Months: M.S.F. has no disclosures to declare. A.E.L. has served as an advisor for AbbVie, Acorda, AFFiRis, Biogen, Denali, Janssen, Lilly, Lundbeck, Maplight, Paladin, Retrophin, Roche, Sun Pharma, Sunovion, Theravance, and Corticobasal Degeneration Solutions; received honoraria from Sun Pharma, AbbVie and Sunovion; received grants from Brain Canada, Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Corticobasal Degeneration Solutions, Edmond J. Safra Philanthropic Foundation, the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Ontario Brain Institute, Parkinson Foundation, Parkinson Canada, and W. Garfield Weston Foundation; received publishing royalties from Elsevier, Saunders, Wiley‐Blackwell, Johns Hopkins Press, and Cambridge University Press. L.K. has received salary support for this work from Canadian Health Institutes of Research (CIHR) Clinician–Scientist Award. In the past year, L.K. has received research support from CIHR, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research, Natural Sciences, and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Ontario Brain Institute, Parkinson Canada, and Toronto General and Western Hospital Foundation; held contracts with ApoPharma and UCB; and, received honoraria from National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Takeda. I.C. has no disclosures to declare. M.S. has no disclosures to declare. G.K. has no disclosures to declare. C.G. is supported by a VolkswagenStiftung Fellowship (Freigeist). He received honoraria for serving as ad hoc advisory board for Biomarin pharmaceutical and Orphazyme, and for educational activities of the Movement Disorder Society. R.P.M. has no disclosures to declare. A.F. has served as an advisor for Apple, AbbVie, Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Sunovion, Chiesi Farmaceutici, UCB, Ipsen, and Rune labs; received honoraria from American Academy of Neurology, AbbVie, Abbott, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Sunovion, Chiesi Farmaceutici, UCB, Ipsen, Paladin Lab, and Movement Disorders Society; received grants from University of Toronto, AbbVie, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, MSA Coalition, and McLaughlin Centre. C.E.P.A. has no disclosures to declare. C.Z.R. has no disclosures to declare.

Relevant disclosures and conflict of interest are listed at the end of this article.

References

- 1. Boutry M, Morais S, Stevanin G. Update on the genetics of spastic paraplegias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2019;19(4):18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sanchez‐Ferrero E, Coto E, Beetz C, Gamez J, Corao AI, Diaz M, et al. SPG7 mutational screening in spastic paraplegia patients supports a dominant effect for some mutations and a pathogenic role for p.A510V. Clin Genet 2013;83(3):257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Estiar MA, Yu E, Haj Salem I, Ross JP, Mufti K, Akcimen F, et al. Evidence for non‐Mendelian inheritance in spastic paraplegia 7. Mov Disord 2021;36(7):1664–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. De la Casa‐Fages B, Fernandez‐Eulate G, Gamez J, Barahona‐Hernando R, Moris G, Garcia‐Barcina M, et al. Parkinsonism and spastic paraplegia type 7: Expanding the spectrum of mitochondrial parkinsonism. Mov Disord 2019;34(10):1547–1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Gassen KL, van der Heijden CD, de Bot ST, den Dunnen WF, van den Berg LH, Verschuuren‐Bemelmans CC, et al. Genotype‐phenotype correlations in spastic paraplegia type 7: A study in a large Dutch cohort. Brain 2012;135(Pt 10):2994–3004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verdura E, Schluter A, Fernandez‐Eulate G, Ramos‐Martin R, Zulaica M, Planas‐Serra L, et al. A deep intronic splice variant advises reexamination of presumably dominant SPG7 cases. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2020;7(1):105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Settasatian C, Whitmore SA, Crawford J, Bilton RL, Cleton‐Jansen AM, Sutherland GR, et al. Genomic structure and expression analysis of the spastic paraplegia gene, SPG7. Hum Genet 1999;105(1–2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hall D, Stong N, Lippa N, Pitman MJ, Pullman SL, Levy OA. Spasmodic dysphonia in hereditary spastic paraplegia type 7. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2018;5(2):221–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schaefer SM, Szekely AM, Moeller JJ, Tinaz S. Hereditary spastic paraplegia presenting as limb dystonia with a rare SPG7 mutation. Neurol Clin Pract 2018;8(6):e49–e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gass J, Blackburn PR, Jackson J, Macklin S, van Gerpen J, Atwal PS. Expanded phenotype in a patient with spastic paraplegia 7. Clin Case Rep 2017;5(10):1620–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Salgado P, Latorre A, Del Gamba C, Menozzi E, Balint B, Bhatia KP. SPG7: The great imitator of MSA‐C within the ILOCAs. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2019;6(2):174–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bellini G, Del Prete E, Unti E, Frosini D, Siciliano G, Ceravolo R. Positive DAT‐SCAN in SPG7: A case report mimicking possible MSA‐C. BMC Neurol 2021;21(1):328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Martinuzzi A, Montanaro D, Vavla M, Paparella G, Bonanni P, Musumeci O, et al. Clinical and Paraclinical indicators of motor system impairment in hereditary spastic paraplegia: A pilot study. PLoS One 2016;11(4):e0153283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pedroso JL, Vale TC, Bueno FL, Marussi VHR, Amaral L, Franca MC Jr, et al. SPG7 with parkinsonism responsive to levodopa and dopaminergic deficit. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2018;47:88–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pfeffer G, Gorman GS, Griffin H, Kurzawa‐Akanbi M, Blakely EL, Wilson I, et al. Mutations in the SPG7 gene cause chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia through disordered mitochondrial DNA maintenance. Brain 2014;137(Pt 5):1323–1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baviera‐Munoz R, Campins‐Romeu M, Carretero‐Vilarroig L, Sastre‐Bataller I, Martinez‐Torres I, Vazquez‐Costa JF, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of 21 Spanish patients with biallelic pathogenic SPG7 mutations. J Neurol Sci 2021;429:118062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coarelli G, Schule R, van de Warrenburg BPC, De Jonghe P, Ewenczyk C, Martinuzzi A, et al. Loss of paraplegin drives spasticity rather than ataxia in a cohort of 241 patients with SPG7. Neurology 2019;92(23):e2679–e2690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]