Abstract

Psychrotolerant polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-degrading bacteria were isolated at 7°C from PCB-contaminated Arctic soil by using biphenyl as the sole organic carbon source. These isolates were distinguished from each other by differences in substrates that supported growth and substrates that were oxidized. 16S ribosomal DNA sequences suggest that these isolates are most closely related to the genus Pseudomonas. Total removal of Aroclor 1242, and rates of removal of selected PCB congeners, by cell suspensions of Arctic soil isolates and the mesophile Burkholderia cepacia LB400 were determined at 7, 37, and 50°C. Total removal values of Aroclor 1242 at 7°C by LB400 and most Arctic soil isolates were similar (between 2 and 3.5 μg of PCBs per mg of cell protein). However the rates of removal of some individual PCB congeners by Arctic isolates were up to 10 times higher than corresponding rates of removal by LB400. Total removal of Aroclor 1242 and the rates of removal of individual congeners by the Arctic soil bacteria were higher at 37°C than at 7°C but as much as 90% lower at 50°C than at 37°C. In contrast, rates of PCB removal by LB400 were higher at 50°C than at 37°C. In all cases, temperature did not affect the congener specificity of the bacteria. These observations suggest that the PCB-degrading enzyme systems of the bacteria isolated from Arctic soil are cold adapted.

Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are synthesized by direct chlorination of biphenyl, resulting in 209 possible congeners. The physical and chemical nature of PCBs, including lipophilicity, heat resistance, and relative inertness, has resulted in their widespread industrial application. The nature of PCBs has also led to their persistence and bioaccumulation and has caused health problems in contaminated organisms (reviewed in references 8 and 15). As a result, the production of most PCBs was banned in the United States in 1976 and in Canada in 1977. However, several locations, including areas in the Canadian Arctic, remain polluted with PCBs. Canadian environmental legislation and aboriginal land settlement agreements require remediation of many of these Arctic sites. Conventional clean-up strategies at such remote locations are very expensive because excavation and transportation of polluted soil to treatment facilities are generally required. Bioremediation of PCBs, then, may be the most cost-effective strategy, since it allows on-site treatment.

Several mesophilic bacteria capable of cometabolizing PCBs via the biphenyl catabolic pathway have been described (1, 8, 13). Most of these organisms are able to degrade biphenyls with up to four chlorine substituents, although bacteria capable of degrading biphenyls with up to seven chlorine substituents have been isolated (5, 9). Bioremediation strategies in Arctic and temperate areas that use cold-adapted PCB-degrading bacteria may be more efficient than strategies using mesophilic PCB-degrading bacteria, since heating requirements for growth and PCB degradation activity may be reduced. In addition, PCB-degrading bacteria indigenous to Arctic soil have presumably adapted to various soil characteristics that limit the survival or activity of foreign PCB-degrading microorganisms. Others have shown removal of biphenyls with as many as three chlorine substituents at 4°C by PCB-contaminated river sediment (28). However, PCB-degrading bacterial isolates from these river sediments have not been reported. Psychrophilic and psychrotolerant PCB-degrading bacteria indigenous to Arctic soils have been reported (21), but such organisms have not been characterized.

In this study we isolated and characterized, for the first time, PCB-degrading psychrotolerant bacteria from PCB-contaminated Arctic soil. We also characterized Sag-50G, a psychrotolerant PCB-degrading bacterium previously isolated (21). The extent and rate of removal of a PCB mixture by each Arctic soil isolate at a range of temperatures were compared with those of the mesophile Burkholderia cepacia LB400 (17) (previously known as Pseudomonas sp. strain LB400 [7]). LB400, compared to most other PCB-degrading bacteria that have been studied, degrades a wide range of PCB congeners (4). Our results suggest that PCB degradation enzymes of the Arctic soil bacterial isolates are cold adapted. Since the psychrotolerant PCB-degrading organisms grow at lower temperatures than mesophiles, such as LB400, and appear to express genes encoding cold-adapted PCB-degrading enzymes, these psychrotolerant isolates are potentially useful for PCB bioremediation at low temperatures.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of PCB-degrading bacteria from Arctic soil samples.

Soil samples were obtained from a Vancouver location or from PCB-contaminated (5 to 100 μg/g of dry soil) or pristine Arctic locations: Saglek, Labrador (57°N, 63°W), Cambridge Bay, Northwest Territories (69°N, 105°W), and Iqaluit, Northwest Territories (63°N, 69°W). Enrichment cultures were prepared with 1.0 g of soil suspended in 100 ml of phosphate-buffered mineral medium (PAS) (6) containing 200 mg of biphenyl (Aldrich)/liter as the sole organic carbon source. The enrichment cultures were incubated on a shaker for 3 weeks at 7°C. Subsequent enrichment cultures had 1% inocula. If growth occurred, 0.1% of the culture was transferred to homologous medium. Enriched cultures were diluted in PAS medium, then spread on PAS with 1.5% purified agar and 200 mg of biphenyl/liter on the agar surface. Distinct colonies were picked, suspended in 2.5 ml of PAS medium with 200 mg of biphenyl/liter, and incubated at 7°C. Isolates which grew were stored at −70°C with 8% dimethyl sulfoxide.

To test PCB removal activities, isolates were inoculated into solvent-washed tubes with Teflon-lined screw caps, containing 2.5 ml of PAS medium with 100 mg of biphenyl/liter, 200 mg of Aroclor 1221 (Accu Standard)/liter, and 10 mg of 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-hexachlorobiphenyl (Accu Standard)/liter as an internal standard, then incubated for 5 weeks at 7°C on a shaker (n = 2). The tubes contained approximately twice the amount of oxygen required to completely mineralize the added biphenyl. After incubation, remaining PCBs were extracted from the cultures with hexane, and the percent removal of PCBs was determined. Uninoculated cultures were used as negative controls.

PCB degradation by cell suspensions.

Arctic soil isolates were grown at 7°C, and B. cepacia LB400 was grown at 15°C in 1-liter cultures to late-logarithmic phase. Remaining biphenyl crystals were allowed to precipitate; then cultures were decanted and centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 10 min and washed with PAS buffer. Final cell suspensions contained 600 to 800 μg of cell protein per ml of buffer. Cell samples of 2.5 ml were transferred to solvent-washed screw-cap tubes with Teflon-lined caps (n = 3). Control cell suspensions were boiled. PCBs (100 mg of Aroclor 1242/liter and 10 mg of 2,2′,4,4′,6,6′-hexachlorobiphenyl/liter) were added to each tube, and then the reaction tubes were incubated at 7, 37, or 50°C. Reaction tubes were transferred to −20°C at regular time intervals over 24 h to stop PCB removal activity. Control tubes were incubated for 0, 4, and 24 h. Initial rates of removal of selected PCB congeners were calculated from the slopes of initially linear curves, generated by plotting the percentage of the PCB congener remaining versus time, and were standardized for protein concentration. The protein concentrations of cultures were determined by a bicinchoninic acid protein assay (2).

Analysis of PCBs.

Remaining PCBs from batch cultures and cell suspensions were extracted twice with an equal volume of hexane. The extracts were pooled, then mixed with Na2SO4 to dry the organic phase. The extracts were analyzed by using a gas chromatograph (GC) equipped with an ion trap mass spectrophotometer (21). The extraction efficiency was 98% ± 0.5%.

The mass spectrum of each GC peak reported verified that it corresponded to a PCB congener with a particular number of chlorine substituents. PCB congeners were identified (Table 1) by comparing the relative retention times of peaks corresponding to PCBs with published chromatographs of Aroclors 1221 and 1242 (12). Relative amounts of PCB congeners were determined by integrating the area under each peak and dividing by the peak area of the internal standard. The percent removal of each PCB congener was calculated by subtracting 100 from percentage values obtained by dividing the relative peak area of a PCB congener in the test sample by the corresponding relative peak area in a control sample and multiplying by 100. Extraction efficiency was determined with a boiled cell suspension.

TABLE 1.

| PCB congener | Aroclor 1221

|

Aroclor 1242

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak no. | Wt %c | Peak no. | Wt %c | |

| 2 | 1 | 42.24 | 1 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 2 | 2.62 | ||

| 4 | 3 | 20.66 | ||

| 2,2′/2,6 | 4 | 6.34/0.05 | 2 | 2.74/0.05 |

| 2,5 | 5 | 2.49 | 3 | 1.02 |

| 2,3′ | 6 | 2.99 | 4 | 1.34 |

| 2,4′ | 7 | 12.88 | 5 | 6.4 |

| 2,6,2′ | 6 | 0.96 | ||

| 3,4 | 8 | 1.34 | ||

| 4,4′/2,5,2′ | 9 | 3.66/0.34 | 7 | 3.19/6.98 |

| 2,4,2′ | 8 | 4.57 | ||

| 2,6,3′ | 10 | 0.5 | 9 | 0.83 |

| 2,3,2′/2,6,4′ | 11 | 0.89/<0.05 | 10 | 5.14/<0.05 |

| 2,5,3′/2,4,3′ | 11 | 1.23/0.89 | ||

| 2,5,4′/2,4,4′ | 12 | 0.87/0.99 | 12 | 6.75/8.01 |

| 3,4,2′/2,5,2′,6′ | 13 | 0.89/0 | 13 | 5.95/0.33 |

| 2,3,4′/2,4,2′,6′ | 14 | 0.79/0 | 14 | 2.79/0.09 |

| 2,3,6,2′ | 15 | 1.1 | ||

| 2,5,2′,5′ | 16 | 3.32 | ||

| 2,4,2′,5′ | 17 | 2.63 | ||

| 2,4,6,4′ | 18 | 1.48 | ||

| 2,3,2′,5′ | 19 | 3.26 | ||

| 3,4,4′/2,3,2′,4′ | 20 | 1.94/1.38 | ||

| 2,3,6,4′ | 21 | 3.11 | ||

| 2,3,2′,3′ | 22 | 1.01 | ||

| 2,4,5,4′ | 23 | 1.6 | ||

| 2,5,3′,4′ | 24 | 3.41 | ||

| 2,4,3′,4′ | 25 | 3.47 | ||

| 2,3,4,4′ | 26 | 2.51 | ||

| 2,3,6,2′,3′ | 27 | 0.76 | ||

| 2,4,5,2′,5′ | 28 | 0.88 | ||

| 2,4,5,2′,4′ | 29 | 0.74 | ||

| 2,4,5,2′,3′ | 30 | 0.72 | ||

| 2,3,4,2′,5′ | 31 | 0.78 | ||

| 2,3,4,2′,4′ | 32 | 0.71 | ||

| 2,3,6,3′,4′ | 33 | 1.0 | ||

| 2,4,5,3′,4′ | 34 | 0.8 | ||

| 2,3,4,3′,4′ | 35 | 0.74 | ||

Twelve carbon atoms, 21% chlorine.

Twelve carbons, 42% chlorine.

The percent composition of each PCB congener was obtained from Frame et al. (12).

Characterization of isolates.

Gram staining, cell size, and motility tests were performed on liquid cultures in late-logarithmic phase. Colony morphology determination, oxidase tests, and catalase tests were performed on colonies grown on PAS agar with biphenyl at 7°C (25). Anaerobic respiration with nitrate by cultures using glucose as a carbon source was tested as previously described (29). The abilities of each isolate to use a range of substrates for growth at 7°C (see Table 3) and to oxidize substrates contained in GN microplates (Biolog, Hayward, Calif.) were also determined. The percent removal of 100 mg of Aroclor 1242/liter at 7°C by Arctic soil isolates growing on primary substrates other than biphenyl was determined by extracting and analyzing remaining PCBs from batch cultures after 5 weeks of incubation (n = 2).

TABLE 3.

Substrate use or oxidation by Arctic soil isolates

| Substrate (mg/liter) | Resulta for:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cam-1 | Sag-1 | Iqa-1 | Sag-50Gb | |

| Fatty acid (linoleic acid [1,000]) | G | G | G | NG |

| Sugars | ||||

| l-Arabinose (1,000) | G | G | NG | G |

| d-Sorbitol | NO | NO | NO | O |

| d-Trehalose | NO | NO | NO | O |

| Aromatic compounds | ||||

| Benzoic acid (240) | G | G | G | NG |

| Biphenyl (200) | G | G | G | G |

| 4-Chlorobiphenyl (200) | G | G | NG | G |

| Naphthalene (200) | G | NG | NG | NG |

| Other compounds | ||||

| α-Keto-valerate | O | NO | NO | NO |

| Acetate (1,000) | G | G | G | G |

| d-Galacturonate | NO | O | NO | NO |

| d-Saccharate | O | O | NO | O |

| Ethanol (200) | NG | NG | G | NG |

| Glycerol (1,000) | G | G | G | G |

| Hydroxy l-proline | NO | NO | NO | O |

| Methyl pyruvate | O | O | NO | O |

| Pyruvate (1,000) | G | G | NG | G |

G, supports growth as sole organic substrate; NG, does not support growth; O, oxidized in Biolog assay; NO, not oxidized in Biolog assay.

Isolated previously from PCB-contaminated Arctic soil (21).

16S rDNA PCR and DNA sequencing.

Cell pellets from 500-μl aliquots of late-logarithmic-phase cultures grown at 7°C with 200 mg of biphenyl/liter were washed with 0.8% NaCl, suspended in 90 μl of sterile, deionized water, and boiled for 10 min. Cell debris was pelleted by brief centrifugation. The 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) was amplified from each isolate by PCR using the reagents and procedures of Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Inc. (Gaithersburg, Md.) and primers hybridizing to positions 8 to 27 and 1541 to 1525 (18). The Oligonucleotide Synthesis Laboratory, University of British Columbia, synthesized these primers. Thermal cycling was performed in a PowerBlock II System (ERICOMP) according to the following program: initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 43°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

PCR products were cloned with a TOPO TA cloning kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Resulting transformants were screened by alkaline lysis (2), followed by digestion of recovered plasmids with EcoRI and checking for 1.6-kb fragments on a 0.8% agarose gel. Nearly complete 16S rDNA sequences were determined by using fluorescent sequencing (FS) Taq terminator chemistry and primers surrounding bases 27 to 1518 (18). Sequencing was performed by the DNA Sequencing Laboratory, University of British Columbia, with a model 373 DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems).

Phylogenetic analysis.

Each 16S rDNA sequence that was determined was compared to other prokaryotic 16S rDNA sequences by using the Similarity_ Rank analysis service of the Ribosomal Database Project (19). The 16S rDNA sequences of the closest relatives to the Arctic soil isolates env. JAP501 (GenBank accession no. U09827), env. JAP412 (GenBank accession no. U09773), and Pseudomonas syringae A501 (GenBank accession no. L24787), as well as representative α-proteobacteria Acetobacter aceti (ATCC 15973), Agrobacterium tumefaciens (ATCC 4720), Sphingomonas capsulata (GIFV 11526), Sphingomonas paucimobilis (ATCC 29837), and Sphingomonas terrae (IFO 15098), β-proteobacteria Alcaligenes denitrificans (ATCC 15173), B. cepacia (ATCC 25416), Comamonas testosteroni (ATCC 11996), Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (ATCC 13637), and Zoogloea ramigera (ATCC 25935), and γ-proteobacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC 10145), Pseudomonas fluorescens (ATCC 13525), Pseudomonas putida (ATCC 12633), Pseudomonas stutzeri (ATCC 17588), and Escherichia coli (GenBank accession no. J01695), were retrieved from the Ribosomal Database Project and aligned with the 16S rDNA sequences of the Arctic soil isolates by using Clustal X. One hundred bootstrapped data sets of the aligned sequences were obtained by using SEQBOOT. Phylogeny estimates for each of these data sets were obtained by using the default parameters of DNADIST. A phylogenetic tree was obtained by analyzing the resulting distance matrices with the default parameters of NEIGHBOR and CONSENSE.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rDNA sequences determined for Cam-1, Sag-1, Iqa-1, and Sag-50G have been deposited in the EMBL Nucleotide Database and have accession numbers AF098464, AF098467, AF098465, and AF098466, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Isolation of PCB degraders.

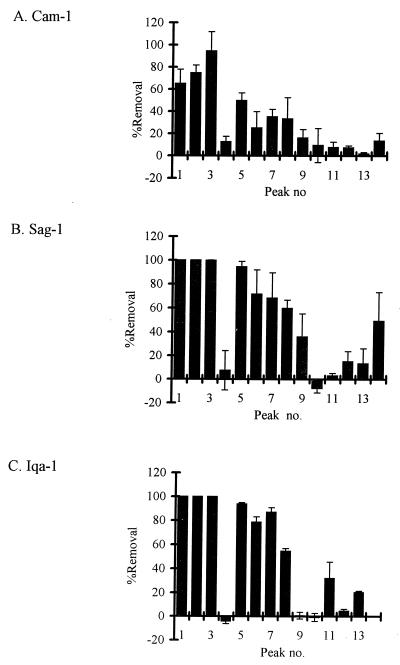

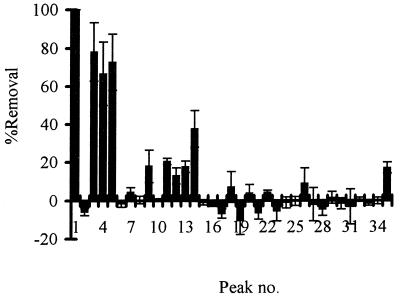

Of approximately 50 biphenyl-degrading bacteria isolated from PCB-contaminated or pristine Arctic soil or pristine Vancouver soil, three (Cam-1, Sag-1, and Iqa-1) could remove PCBs. Interestingly, all of the PCB-degrading isolates were obtained from PCB-contaminated Arctic soil samples; no PCB-degrading bacteria were isolated from pristine soil samples. Most of the PCB congeners present in Aroclor 1221 were removed at 7°C by batch cultures of the three Arctic soil isolates identified above, albeit to different extents (Fig. 1; Table 2). The congener ranges of these isolates were similar to the congener range of Sag-50G, which was previously reported (21). None of the isolates could remove 2,2′-chlorobiphenyl, although Cam-1 and Sag-1 did remove 4,4′-chlorobiphenyl. This result is consistent with results for other PCB-degrading bacteria that express 2,3-biphenyl dioxygenase activity and not 3,4-biphenyl dioxygenase activity (4). We also tested removal of Aroclor 1242 at 7°C and at 15°C by batch cultures of each isolate. The total removal of Aroclor 1242 by Cam-1 and Sag-1 was approximately 30 and 15% higher at 15°C than at 7°C, respectively (Table 2). However, the total removal of Aroclor 1242 by Iqa-1 was approximately 30% higher at 7°C than at 15°C. Differences in relative removal (per unit of final biomass) were consistent with differences in absolute removal. The range of Aroclor 1242 congeners removed by each of the isolates at 7 and 15°C was similar to the range of congeners removed by Cam-1 at 7°C (Fig. 2) and to those of most mesophilic PCB-degrading bacteria that have been reported (reviewed in reference 1). Cam-1 also appeared to remove some tetrachlorobiphenyls (peaks 18, 21, and 26) at 15°C. The removal of 2,3,4,3′,4′-pentachlorobiphenyl by Cam-1 was considered unlikely, since removal of 2,5,3′,4′- and 2,4,3′,4′-tetrachlorobiphenyl was not observed. However, the position of chlorine substituents, and not only the number of chlorine substituents, can determine whether a PCB congener is degraded (4). Experiments showing removal of pure tetrachlorobiphenyls and 2,3,4,3′,4′-pentachlorobiphenyl would be required to confirm that Cam-1 can remove such PCB congeners.

FIG. 1.

Percent removal of major congeners in Aroclor 1221 by batch cultures of Arctic soil isolates incubated at 7°C for 5 weeks (n = 2; error bars indicate ranges). Peaks are identified in Table 1.

TABLE 2.

Relative and absolute removal of Aroclors 1221 and 1242 by batch cultures incubated at 7 or 15°C for 5 weeks

| Soil isolate | Relative removal (absolute removal)a of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aroclor 1221 at 7°C (n = 2) | Aroclor 1242 at:

|

||

| 7°C (n = 3) | 15°C (n = 3) | ||

| Cam-1 | 10.3 (56.0) | 2.0 ± 0.36 (11.3 ± 2.0) | 2.6 ± 0.52 (14.4 ± 3.0) |

| Sag-1 | 11.7 (82.1) | 1.2 ± 0.34 (8.1 ± 2.4) | 1.4 ± 0.41 (10.2 ± 3.4) |

| Iqa-1 | 8.7 (87.3) | 0.80 ± 0.10 (7.1 ± 1.0) | 0.56 ± 0.10 (5.3 ± 1.0) |

Relative removal is expressed as micrograms of PCBs removed per milligram of cell protein; absolute removal is expressed as a percentage. Values are means ± standard deviations.

FIG. 2.

Percent removal of major congeners in Aroclor 1242 by a batch culture of Cam-1 incubated at 7°C for 5 weeks (n = 3; error bars indicate standard deviations). Peaks are identified in Table 1.

Morphology, physiology, and phylogeny.

All of the PCB-degrading bacteria isolated were most closely related to the genus Pseudomonas. Both physiological analyses and 16S rDNA sequence analyses support this conclusion. All isolates were gram-negative, catalase-positive, motile rods. Cam-1 and Iqa-1 were oxidase positive; Sag-1 was oxidase negative. The isolates were obligately aerobic and failed to grow anaerobically on glucose, fermentatively or with nitrate. When grown on biphenyl at 7°C, Cam-1 cells were 1.5 to 3.0 by 1.0 μm, Sag-1 cells were 1.5 to 4.0 by 1.0 μm, and Iqa-1 cells were 1.2 to 4.0 by 1.0 μm. On PAS agar with biphenyl, colonies of each isolate were circular with a slightly undulate edge, convex, butyrous, smooth, grey, and opaque, except for Sag-1, which was translucent. The use of different primary growth substrates and oxidation of test substrates in GN Biolog plates (Table 3) confirmed that these isolates are distinct from each other and from Sag-50G. All of the Arctic soil isolates used glucose and galactose as primary growth substrates. None of the Arctic soil isolates used 2-chlorobiphenyl, 3-chlorobiphenyl, camphor, citronellol, cymene, dehydroabietic acid, limonene, methanol, n-hexadecane, pentachlorophenol, phenol, or pinene as primary growth substrates.

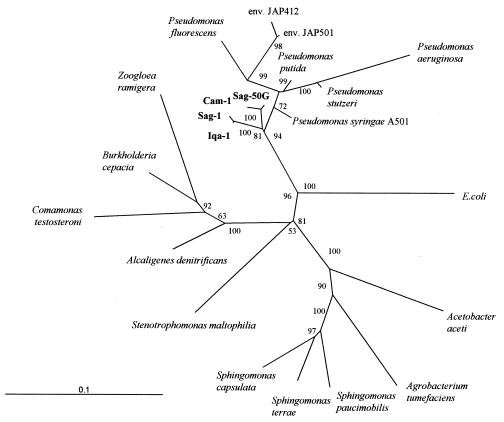

The 16S rDNA sequences of Cam-1 and Sag-50G were most similar to that of Pseudomonas sp. strain JAP501 (similarity rank [Sab] = 0.931 and 0.935, respectively), the 16S rDNA sequence Sag-1 was most similar to that of Pseudomonas sp. strain JAP412 (Sab = 0.858), and the 16S rDNA sequence Iqa-1 was most similar to that of P. syringae A501 (Sab = 0.845). JAP501 and JAP412 are 16S rDNA clones obtained from deep marine environments (23). The organisms represented by these clones may be psychrotolerant. A501 has been studied to investigate expression of an ice nucleation gene (10); however, its physiology was not described. The phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rDNA sequences of the Arctic soil isolates (Fig. 3) suggests that these organisms are most closely related to the genus Pseudomonas.

FIG. 3.

Unrooted tree showing phylogenetic relationships of Arctic soil isolates (in bold) and representative members of α-, β-, and γ-proteobacteria. The phylogenetic tree was generated with nearly complete 16S rDNA sequences. The scale shows evolutionary distance. Numbers indicate bootstrap values.

Effect of primary substrate on PCB degradation.

Arctic soil isolates growing on primary substrates other than biphenyl also partially removed Aroclor 1242. Compared to relative removal of Aroclor 1242 in cultures growing on biphenyl, relative removal was lower in cultures growing on all other primary substrates (Table 4). Exceptions were linoleic acid-grown and, to a lesser extent, pyruvate-grown cultures of Sag-1, whose relative removals were higher than those of biphenyl-grown cultures. Partial removal of monochlorobiphenyls and of some di- and tri-chlorobiphenyls was detected in cultures of each isolate growing on linoleic acid, glucose, glycerol, acetate, or pyruvate. Cultures of Cam-1 and Sag-1 growing on benzoate failed to remove PCBs. Cultures of Sag-50G growing on benzoate removed comparatively small amounts of the PCB mixture. It is possible that benzoate inhibits induction of the biphenyl operon in these organisms, since benzoate is an end product of the biphenyl degradative pathway. In some cases, substrates supported similar absolute removals, but different relative removals, of Aroclor 1242 by a particular isolate. Therefore, primary substrates affect PCB removal by affecting both cell density and the efficiency of PCB removal by a constant amount of biomass.

TABLE 4.

Relative and absolute removal of Aroclor 1242 by batch cultures grown on different primary substratesa

| Substrate | Relative removal (absolute removal)b by:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cam-1 | Sag-1 | Iqa-1 | Sag-50G | |

| Linoleic acid | 1.2 (3.5) | 3.0 (9.9) | 1.3 (14.6) | NG (0) |

| Glucose | 0.42 (7.4) | 0.20 (2.6) | 0.17 (4.1) | 0 (0) |

| Glycerol | 1.0 (16.2) | 1.2 (7.2) | 0.10 (3.2) | 1.0 (4.3) |

| Benzoate | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.10 (0.6) | 0.03 (0.16) |

| Acetate | 0.42 (2.3) | 0.39 (1.6) | 0.15 (0.9) | 0.20 (0.7) |

| Pyruvate | 1.0 (8.4) | 1.4 (13.8) | NG (0) | 0.47 (3.9) |

| Biphenyl | 2.2 (11.3) | 1.1 (8.1) | 1.3 (11.3) | 0.45 (2.2) |

All cultures were incubated at 7°C for 5 weeks (n = 2).

Relative removal is expressed as micrograms of PCBs removed per milligram of cell protein; absolute removal is expressed as a percentage. NG, no growth on primary substrate.

Biphenyl has traditionally been used as the growth substrate for PCB-degrading bacteria when PCB removal is measured because biphenyl induces the biphenyl catabolic pathway (3, 16). Since biphenyl is toxic, it is important for field applications to determine whether other growth substrates can support PCB removal by certain bacteria. Here we demonstrated that growth substrates other than biphenyl could support PCB removal by the Arctic soil isolates. This suggests constitutive expression of genes involved in PCB degradation in these organisms or possible induction of the biphenyl operon by alternative substrates such as linoleic acid or Aroclor 1242. The substrates tested, however, would also enrich indigenous microorganisms that do not degrade PCBs. The use of these substrates to support the growth of PCB-degrading bacteria in field experiments, then, may require initial steps to retard the growth of competing non-PCB-degrading bacteria (27). Additional studies are required to determine whether, and to what extent, growth substrates other than biphenyl genetically induce the genes encoding biphenyl degradation in these Arctic soil isolates.

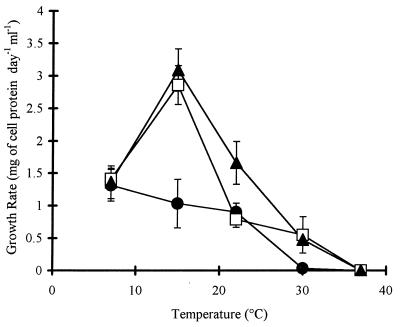

Temperature optimum for growth.

With biphenyl as their organic substrate, Cam-1 and Iqa-1 grew optimally at 15°C, and Sag-1 grew optimally at 7°C (Fig. 4). Up to 2 weeks of incubation at 7°C were required before growth was detected, and the exponential phase continued up to 3 days. The mesophile B. cepacia LB400 did not grow at 7°C but did grow at 15 and 37°C. Temperatures higher than 37°C were not tested. Psychrophilic and psychrotolerant bacteria are defined by optimal growth at temperatures below 20°C and growth at temperatures as low as 0°C. Psychrotolerant bacteria are distinguished by growth at temperatures above 20°C (22). Since Cam-1, Iqa-1, and Sag-1 grew at 22°C, these organisms are psychrotolerant rather than psychrophilic bacteria.

FIG. 4.

Growth rates of Arctic soil isolates grown on biphenyl at various temperatures (n = 3; error bars indicate standard deviations). □, Cam-1; •, Sag-1; ▴, Iqa-1.

Physiological characteristics generally observed in psychrophilic and psychrotolerant bacteria include increased fluidity of cell membranes resulting from decreased saturation and shortening of fatty-acyl residues (reviewed in references 14 and 24). Cold adaptation of enzymes encoded by psychrophilic and psychrotolerant organisms may also occur to compensate for decreased kinetic energy at low temperatures (11). Such physiological and genetic changes may exist in the bacteria that we isolated from Arctic soil and may affect PCB removal by these organisms. To test this possibility, we compared the removal of PCBs by cell suspensions of the Arctic isolates and LB400 at several temperatures.

PCB degradation by cell suspensions.

High rates of PCB removal at low temperatures and the temperature sensitivity of PCB removal activity suggest that PCB degradation enzymes expressed by the Arctic soil bacteria are cold adapted. The ranges of PCBs removed by cell suspensions of Arctic soil isolates at 7°C (data not shown) did not differ from those of batch cultures growing at 7°C (Fig. 2). Although no significant removal of peak 10 by Cam-1 was detected, an initial rate of removal was evident (Table 5). Cam-1 probably removed 2,6,4′-trichlorobiphenyl, which is a minor component of peak 10, rather than 2,3,2′-trichlorobiphenyl, which is the major component of peak 10. The inability of Cam-1 to remove 2,3,2′-trichlorobiphenyl seems consistent with its inability to remove other 2,2′-substituted biphenyls. The range of PCBs removed by B. cepacia LB400 differed from those of the Arctic soil isolates, since LB400 could remove 2,2′-dichlorobiphenyl. No significant differences in relative areas of peaks corresponding to PCBs on gas chromatographs were detected between psychrotolerant killed cells and LB400 killed cells or between killed cell controls incubated for different times.

TABLE 5.

Initial rates of removal of selected Aroclor 1242 PCB congeners by cell suspensions incubated at 7°C (n = 2)

| Peak no. | Congener | Rate of removal (μg h−1 g of cell protein−1) by cell suspensions of:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB400 | Cam-1 | Sag-1 | Iqa-1 | Sag-50G | ||

| 1 | 2 | 105 | 323 | 196 | 360 | 151 |

| 2 | 2,2′/2,6 | 362 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 2,5 | 55 | 108 | 123 | 147 | 109 |

| 4 | 2,3′ | 45 | 209 | 162 | 173 | 116 |

| 5 | 2,4′ | 229 | 982 | 772 | 1,150 | 1,048 |

| 6 | 2,6,2′ | 34 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 4,4′/2,5,2′ | 73 | 150 | 0 | 0 | 315 |

| 8 | 2,4,2′ | 78 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | 2,6,3′ | 36 | 91 | 13 | 18 | 0 |

| 10 | 2,3,2′/2,6,4′ | 24 | 303 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 2,5,3′/2,4,3′ | 27 | 200 | 64 | 160 | 113 |

| 12 | 2,5,4′/2,4,4′ | 106 | 784 | 222 | 106 | 0 |

| 13 | 3,4,2′/2,5,2′,6′ | 76 | 389 | 189 | 564 | 0 |

| 14 | 2,3,4′/2,4,2′,6′ | 33 | 247 | 174 | 176 | 308 |

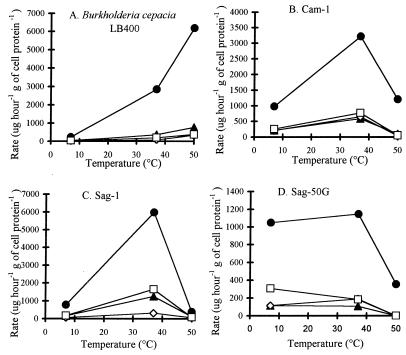

The initial rates of removal of selected PCB congeners at 7°C were generally higher in the Arctic soil isolates than in LB400 (Table 5). Corresponding rates were higher at 37°C than at 7°C for Cam-1 and Sag-1 (Fig. 5B and C). The rates of removal of corresponding congeners at 37°C by Sag-1 were higher than those of Cam-1. The rates of removal of corresponding congeners at 37°C by Sag-1 and Cam-1 were higher than that of LB400 (Fig. 5A through C). The increase in corresponding rates was less for Sag-50G, and rates of removal of certain congeners were lower at 37°C than at 7°C (Fig. 5D). At 50°C, initial rates of PCB removal by the Arctic soil isolates decreased significantly, falling to zero for some congeners (Fig. 5B through D). However, the initial rates of removal of selected PCB congeners by LB400 continued to increase (Fig. 5A). The rates of removal of selected congeners by Iqa-1 at 7, 37, and 50°C were similar to those for Sag-1 (data not shown). The total removal of Aroclor 1242 by the Arctic soil isolates at 37°C was greater than, or the same as, that at 7°C but as much as 90% less at 50°C (Table 6). Differences in relative removal were consistent with differences in absolute removal. These results suggest that PCB removal by the psychrotolerant bacteria is temperature sensitive.

FIG. 5.

Rates of degradation of individual PCB congeners in Aroclor 1242 by cell suspensions at various temperatures (n = 2). ▴, peak 4; •, peak 5; ◊, peak 12; □, peak 14. Peaks are identified in Table 1.

TABLE 6.

Relative and absolute removal of Aroclor 1242 by cell suspensions incubated at various temperatures for 24 h

| Isolate | Relative removal (absolute removal)a at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 7°C | 37°C | 50°C | |

| LB400 | 3.6 ± 0.52 (10.1 ± 1.5) | 11.1 ± 3.6 (31.0 ± 9.5) | 10.0 ± 0.25 (27.8 ± 0.7) |

| Cam-1 | 2.7 ± 0.58 (9.1 ± 2.0) | 5.2 ± 0.50 (17.6 ± 1.7) | 0.43 ± 0.05 (1.4 ± 0.2) |

| Sag-1 | 2.3 ± 0.10 (7.5 ± 0.3) | 1.7 ± 0.60 (5.5 ± 2.0) | 0.63 ± 0.33 (2.0 ± 1.1) |

| Iqa-1 | 2.2 ± 0.45 (6.2 ± 1.3) | 2.2 ± 0.33 (6.2 ± 0.9) | 1.3 ± 0.43 (3.6 ± 1.2) |

| Sag-50G | 0.88 ± 0.40 (3.2 ± 1.5) | 2.5 ± 0.48 (8.8 ± 1.7) | 0.28 ± 0.43 (1.0 ± 1.5) |

Relative removal is expressed as micrograms of PCBs removed per milligram of cell protein; absolute removal is expressed as a percentage. Values are means ± standard deviations (n = 3).

PCB degradation by cell suspensions of the Arctic soil isolates at temperatures above the growth temperature for these bacteria is consistent with other observations of higher optimal temperatures for enzyme activity than for growth of the organism (24). At 7°C, the Arctic soil isolates removed PCB congeners at higher initial rates than B. cepacia LB400. Similar total removal of Aroclor 1242 after 24 h by these bacteria and LB400 may reflect the broader substrate range of LB400 or may suggest that PCB removal by LB400 is less susceptible to inhibiting metabolites, cell starvation, and depletion of reductant. Also, higher initial rates of removal of PCB congeners at 37°C by the Arctic soil isolates than by LB400, but higher total removal of Aroclor 1242 by LB400 after 24 h, suggests that the PCB-degrading enzymes in the Arctic soil isolates are temperature sensitive.

This investigation suggests that PCB bioremediation in the Arctic using psychrotolerant organisms could be the most cost-effective strategy, since, unlike mesophiles such as LB400, these organisms could grow and remove PCBs at high initial rates without heating. It is possible that these isolates would be advantageous for bioremediation in temperate regions as well, due to physiological and genetic adaptations to cold environments which enhance pollutant degradation activity (14). Psychrotolerant organisms may adapt to living at low temperatures by means of several strategies, including altering cell membrane composition, up or down regulating certain genes, and modifying enzymes to act efficiently at low temperatures. Cold-adapted enzymes are defined by their relative thermolability, increased flexibility, and higher activity at low temperatures compared to mesophilic and thermophilic homologs (11, 20, 26). Higher rates of PCB removal at 7°C by the Arctic soil isolates than by the mesophile B. cepacia LB400 and decreased PCB removal at high temperatures by the Arctic soil isolates are consistent, then, with expression of cold-adapted PCB-degrading enzymes in these isolates. In this case, it would be useful to determine whether such enzymes can be stabilized and retain high catalytic efficiency. It is possible, however, that the cell membrane composition of the psychrotolerant organisms facilitates transport of PCB congeners at low and perhaps moderate temperatures, thereby increasing levels of PCB substrates available to degradative enzymes in these microorganisms. In this case, the temperature sensitivity of PCB removal by the Arctic soil isolates may result from disruption of the membrane potential due to membrane leakage. We are currently investigating these possibilities to reveal important rate-limiting determinants of microbial degradation of PCBs and of pollutants in general, which are important for the development of bioremediation strategies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Environmental Science Group of the Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, for providing the soil samples; L. Eltis for providing B. cepacia LB400, Bianca Kuipers and Gordon Stewart for advice on PCB analyses, and Vince Martin for helpful discussions.

This research was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Department of Northern and Indian Affairs, the Canadian Department of National Defense, and a University of British Columbia Graduate Fellowship to E.R.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abramowicz D A. Aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of PCBs: a review. Bio/Technology. 1990;10:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Short protocols in molecular biology. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Greene Publishing Associates and John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barriault D, Sylvestre M. Factors effecting PCB degradation by an implanted bacterial strain in soil microcosms. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:594–602. doi: 10.1139/m93-086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bedard D L, Haberl M L. Influence of chlorine substitution pattern on the degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by eight bacterial strains. Microb Ecol. 1990;20:97–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02543870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bedard D L, Wagner R E, Brennan M J, Haberl M L, Brown J F., Jr Extensive degradation of Aroclors and environmentally transformed polychlorinated biphenyls by Alcaligenes eutrophus H850. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1094–1102. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.1094-1102.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bedard D L, Unterman R, Bopp L H, Brennan M J, Haberl M L, Johnson C. Rapid assay for screening and characterizing microorganisms for the ability to degrade polychlorinated biphenyls. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1986;51:761–768. doi: 10.1128/aem.51.4.761-768.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bopp L H. Degradation of highly chlorinated PCBs by Pseudomonas strain LB400. J Ind Microbiol. 1986;1:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle A W, Silvin C J, Hassett J P, Nakas J P, Tanenbaum S W. Bacterial PCB biodegradation. Biodegradation. 1992;3:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Commandeur L C M, May R J, Mokross H, Bedard D L, Reineke W, Govers H A J, Parsons J R. Aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by Alcaligenes sp. JB1: metabolites and enzymes. Biodegradation. 1996;7:435–443. doi: 10.1007/BF00115290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards A R, Van Den Bussche R A, Wichman H A, Orser C S. Unusual pattern of bacterial ice nucleation gene evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 1994;11:911–920. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feller G, Narinx E, Arpigny J L, Aittaleb M, Baise E, Genicot S, Gerday C. Enzymes from psychrophilic organisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frame G M, Wagner R E, Carnahan J C, Brown J F, Jr, May R J, Smullen L A, Bedard D. Comprehensive, quantitative, congener-specific analyses of eight Aroclors and complete PCB congener assignments on DB-1 capillary GC columns. Chemosphere. 1996;33:603–623. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa K. Molecular genetics and evolutionary relationship of PCB-degrading bacteria. Biodegradation. 1994;5:289–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00696466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gounot A. Bacterial life at low temperature: physiological aspects and biotechnological implications. J Appl Bacteriol. 1991;71:386–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1991.tb03806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson M S, Leah R T, Connor L, Rae C, Saunders S. Polychlorinated biphenyls in small mammals from contaminated landfill sites. Environ Pollut. 1996;92:185–191. doi: 10.1016/0269-7491(95)00096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kohler H P E, Kohler-Staub D, Focht D D. Cometabolism of polychlorinated biphenyls: enhanced transformation of Aroclor 1254 by growing bacterial cells. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1940–1945. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.1940-1945.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumamaru T, Suenaga H, Mitsuoka M, Watanabe T, Furukawa K. Enhanced degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls by direct evolution of biphenyl dioxygenase. Nat Biotechnol. 1998;16:663–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt0798-663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lane D J. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematics. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1991. pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen N, Olsen G J, Maidak B L, McCaughey M J, Overbeek R, Macke T J, Marsh T L, Woese C R. The ribosomal database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3021–3023. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.13.3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marshall C J. Cold-adapted enzymes. Trends Biotechnol. 1997;15:359–364. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01086-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mohn W W, Westerberg K, Cullen W R, Reimer K J. Aerobic biodegradation of biphenyl and PCBs by Arctic soil microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3378–3384. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3378-3384.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita R Y. Psychrophilic bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1975;39:144–167. doi: 10.1128/br.39.2.144-167.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rochelle P A, Cragg B A, Fry J C, Parkes R J, Weightman A J. Effect of sample handling on estimation of bacterial diversity in marine sediments by 16S rRNA gene sequence analysis. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1994;15:215–226. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell N J. Cold adaptation of microorganisms. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1990;326:595–611. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1990.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smibert R M, Kreig N R. Phenotypic characterization. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 607–655. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somero G N. Temperature as a selective factor in protein evolution: the adaptational strategy of compromise. J Exp Zool. 1975;194:175–188. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401940111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Veen J A, van Overbeek L S, van Elsas J D. Fate and activity of microorganisms introduced into soil. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1997;61:121–135. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.61.2.121-135.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams W A, May R J. Low-temperature microbial aerobic degradation of polychlorinated biphenyls in sediment. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:3491–3496. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson A E J, Moore E R B, Mohn W W. Isolation and characterization of isopimaric acid-degrading bacteria from a sequencing batch reactor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3146–3151. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.9.3146-3151.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]