Abstract

Pancreatic β-cell lipotoxicity is a central feature of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. To study the mechanism by which fatty acids cause β-cell death and develop novel approaches to prevent it, a high-throughput screen on the β-cell line INS1 was carried out. The cells were exposed to palmitate to induce cell death and compounds that reversed palmitate-induced cytotoxicity were ascertained. Hits from the screen were analyzed by an increasingly more stringent testing funnel, ending with studies on primary human islets treated with palmitate. MAP4K4 inhibitors, which were not part of the screening libraries but were ascertained by a bioinformatics analysis, and the endocannabinoid anandamide were effective at inhibiting palmitate-induced apoptosis in INS1 cells as well as primary rat and human islets. These targets could serve as the starting point for the development of therapeutics for type 2 diabetes.

Keywords: Islet, Diabetes, Beta-cell, Lipotoxicity

1. Introduction

A fundamental aspect of the current paradigm of type 2 diabetes pathogenesis is that fatty acids have deleterious effects on pancreatic β-cell function and survival. This has been demonstrated in numerous studies, both in vitro and in vivo, in which β-cells exposed to fatty acids exhibit defects in glucose-responsive insulin secretion and ultimately die, generally by apoptosis. Thus, there has been great interest in approaches to inhibiting deleterious effects on β-cells induced by fatty acids. Numerous compounds and genes that are involved in many distinct signaling pathways have been reported to protect β-cells from the effects of fatty acids [1–6], but those have been discovered by candidate approaches based on a priori knowledge and predictions about the mechanisms by which fatty acids affect β-cells. By assaying large numbers of compounds, an unbiased approach using high-throughput screening (HTS) has the potential to uncover previously unknown compounds and pathways that affect β-cell function and survival.

Here, we report the development of an assay for fatty acid-induced β-cell death and its use to screen a library of known drugs for those that inhibit β-cell death induced by fatty acids. The assay is based on INS1 cells, a commonly used cell line derived from a radiation induced, transplantable insulinoma that developed in inbred New England Deaconess Hospital albino rats [7,8]. This cell line is susceptible to apoptosis induced by palmitate and has been used to study pathways that contribute to that process [9].

To determine the identity of the targets of the positive compounds that inhibited lipotoxicity, we used an additional bioinformatics approach called the Kinase Inhibitors Elastic Net (KIEN) method [10]. Hits from the screen and the KIEN method analysis were tested in an increasingly more stringent testing funnel, ending with studies on primary rat and human islets treated with palmitate.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

INS1 832/13 [11] and INS1E cells [12] were cultured in DMEM (11 mM glucose, Corning, Manassas, VA, USA, with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and RPMI (11 mM glucose, Gibco, 5% FBS), respectively, and T6PNE cells were maintained in RPMI (5.5 mM glucose, Corning, 10% FBS). Cell lines were cultured with 1% penicillin/streptomycin (pen-strep, Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

2.2. Preparation of palmitate-BSA complex

Palmitate (150 mM) (Sigma-Aldrich) was prepared in 50% ethanol and precomplexed with 15% fatty acid-free BSA (Research Organics, Cleveland, OH, USA) in a 37 °C water shaker (PMID 25967901). Finally, BSA-precomplexed palmitate was used as a 12 mM stock solution for all assays. For some experiments, palmitate (50 mM) was dissolved in 90% ethanol and diluted to a final concentration of 0.5 mM in medium containing 0.67 to 0.75% fatty acid-free BSA [13].

2.3. Compound library screening with INS1 832/13 cells

To determine assay conditions, a dose response curve was generated with INS1 832/13 cells, ranging from 2500 to 24,000 cells per well of a 384 well plate in the presence and absence of 0.75 mM palmitate. The best signal to noise ratio was obtained with 10,000 cells per well. For HTS, cells were seeded at 10,000 cells per well in 384-well tissue culture plates (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC, USA) in the presence of 25 mM glucose, 1% FBS and 0.75 mM palmitate and fatty acid-free BSA. 2025 Compounds (active compound in DMSO) or DMSO were added at a final concentration of 10 μM with the Echo (Labcyte, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Each plate contained palmitate as negative control and BSA as positive one with DMSO. Two days after addition of compounds, ATP levels were measured. HTS was performed in the SBP Conrad Prebys Center for Chemical Genomics (CPCCG). Selected hits were purchased for secondary assays (Table 3).

Table 3.

Compounds for confirmatory assays.

| Chemical name | Supplier | Location |

|---|---|---|

| HSP90 Inhibitor, CCT018159 | MILLIPORE | Overijse; Belgium |

| PIM1/2 Kinase Inhibitor VI | MILLIPORE | Overijse; Belgium |

| Syk Inhibitor | MILLIPORE | Overijse; Belgium |

| PIKfyve Inhibitor | MILLIPORE | Overijse; Belgium |

| JNK Inhibitor V | MILLIPORE | Overijse; Belgium |

| Anandamide (20:3,n-6) | Sigma-Aldrich | Overijse; Belgium |

| AS605240 PI 3-Kg Inhibitor | Sigma-Aldrich | Overijse; Belgium |

| IRAK-1/4 Inhibitor I | Sigma-Aldrich | Overijse; Belgium |

| Lynestrenol | Sigma-Aldrich | Overijse; Belgium |

| Indirubin-3-oxime | Sigma-Aldrich | St. Louis, MO, USA |

| MAP4K4 inhibitor | SBP CPCCG | La Jolla, CA, USA |

| PIK3CB inhibitor | Cayman Chemical | Michigan, USA |

2.4. Hit confirmation with siRNA and shRNA

Candidates from a list based on assay hits and bioinformatic analysis were studied using siRNA if expressed in the human islet cell line T6PNE [14]. Each mRNA was targeted by a mixture of 4 separate siRNAs that were pooled. Pooled siRNAs were manufactured by Ambion (Waltham, MA, USA). Transfection of T6PNE cells was done by mixing 2 μL of each siRNA (1 μM stock) and 20 μL of diluted Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) (1:100 in Opti-MEM) in a well of a 96-well plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), followed by incubation for 30 min at room temperature. T6PNE cells (1000 cells per well) diluted in 80 μL of RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% pen-strep were added to the transfection mix and incubated for 2 days at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Transfected cells were incubated at 37 °C for an additional 2 days with tamoxifen, 0.25 mM palmitate or BSA followed by measurement of ATP level. For siRNA validation, cells were harvested for RNA purification and QPCR 2 days after transfection with target gene or scrambled siRNA. shRNAs were from (Sigma-Aldrich).

2.5. qPCR

RNA was purified using RNeasy Kits (Qiagen, MD, USA), then converted to cDNA using the qScript cDNA SuperMix (Quanta BioSciences, Beverly, MA, USA). qPCR was conducted on cDNA corresponding to 2 μg of RNA using an ABI 7900HT (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and qPCR SuperMix (BioPioneer, San Diego, CA, USA). All mRNA values were normalized to 18S rRNA values and are expressed as fold change over vehicle treated control.

2.6. MAP4K4 inhibitor synthesis and testing

Compound 1 (6-(2-Fluoropyridin-4-yl)pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidin-4-amine) was synthesized following the literature procedure (Compound 29 in Ref. 33) to >95% purity by LC-MS and 1H NMR.

2.7. XTT assay

XTT assay reagent (Roche) incubated for 3.5 h in 96well plate as per the manufacturer’s directions and measured with ELISA reader (OPTI MAX, Molecular Device).

2.8. ATP Lite Assay

ATP level was measured using the ATPlite 1step Luminescence Assay System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s directions.

2.9. Assessment of apoptosis by Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide assay

Apoptotic cell death was detected by fluorescence microscopy after staining with DNA binding dyes Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/ml; Sigma) and propidium iodide (5 μg/ml, Sigma) [15]. The percentage of viable, apoptotic and necrotic cells was determined after staining with the DNA-binding dyes Propidium Iodide (PI, 5 μg/ml, Sigma) and Hoechst 33342 (HO, 5 μg/ml, Sigma) [16]. This method is quantitative, and has been validated by systematic comparison against electron microscopy [17] and several other well-characterized methods, including fluorometric caspase 3 & 7 assays and determination of histone-complexed DNA fragments by ELISA [16,18–20]. A minimum of 500 cells were counted in each experimental condition. Viability was evaluated by two independent observers, one of them being unaware of sample identity. The agreement between findings obtained by the two observers was >90%.

2.10. Rat and human islets

Pancreatic islets were isolated from male Wistar rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA), housed and handled following the rules of the Belgian Regulations for Animal Care and with approval of the ULB Ethics Committee, and cultured in Ham’s F-10 medium (Invitrogen) containing 10 mM glucose, no FBS and 0.75% fatty acid-free BSA. These culture conditions are based on earlier studies showing optimal function and survival of rat islet cells in vitro at 10 mM glucose [21].

Human islets were isolated from 7 organ donors (age 76 ± 3 years; 4 women/3 men; body mass index 27 ± 1 kg/m2; cause of death cerebral hemorrhage) in Pisa, Italy, with the approval of the Ethics Committee. The human islets were cultured in Ham’s F-10 medium containing 6.1 mM glucose, 2 mM GlutaMAX, 50 μM 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, 1% charcoal absorbed BSA, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 μg/ml streptomycin [13]. Studies with human islets were performed at 6.1 mM glucose, as we have previously shown that glucose concentrations in the range of 5.6–6.1 are ideal to preserve human islet function in culture [22]. In contrast with clonal β-cell lines, lipotoxicity is not potentiated by increasing glucose concentrations in human islets [15]; hence these experiments were performed at 6.1 mM glucose. The percentage of β-cells in the human islet preparations, assessed following staining with anti-insulin antibody [23], was 63 ± 3%.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM of n independent experiments. Comparisons were performed by two-sided paired t-test. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Development of an assay for palmitate induced killing of INS1 cells

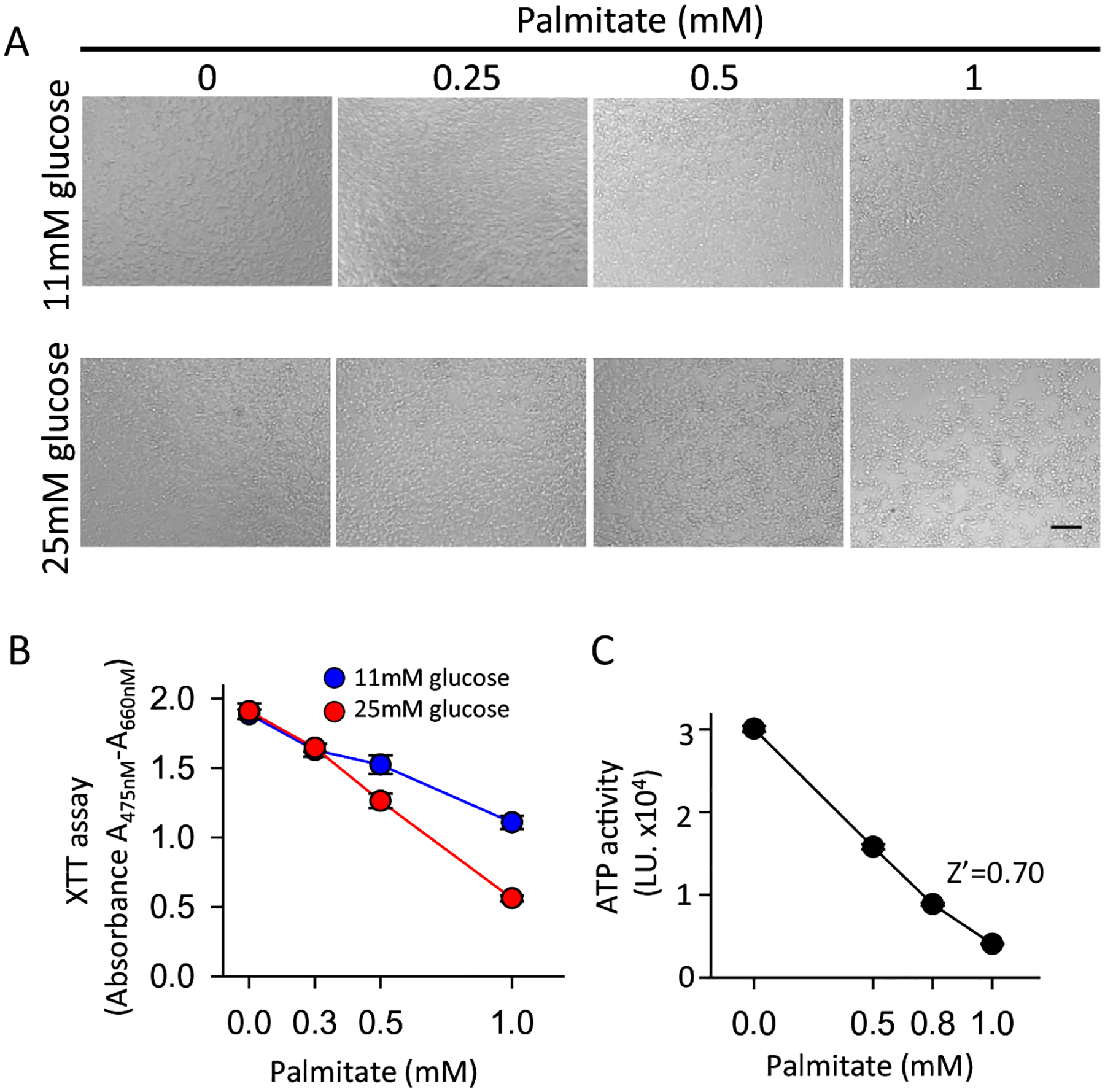

To develop an assay for fatty acid induced lipotoxicity, we first constructed a dose response curve for palmitate-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 1). Dose-responsive loss of cells was observable in the wells (Fig. 1A) and that was confirmed by XTT assay (Fig. 1B). For HTS, we used ATP level as determined by ATPLite luciferase activity, which is well suited for screening and has been shown to be an accurate measure of cellular viability, and thus should reflect a decrease in cell number caused by apoptosis, although it does not directly measure apoptosis (Fig. 1C) [24]. The optimal assay condition was determined to be 0.75 mM palmitate in 1% FBS at 25 mM glucose. Consistent with the findings of others, substantially elevated glucose concentration was required for maximal induction of palmitate-induced apoptosis [25]. Under those conditions, the Z’ [26] for the assay was 0.70, well above the value considered appropriate for conducting HTS.

Fig. 1.

Development of the lipotoxicity assay. INS1 832/13 cells were incubated with the indicated concentration of palmitate for 2 days with 1% FBS and XTT assay was used to measure cell viability. (A) Light microscopic image of treated cells. (B) XTT assay in 11 mM and 25 mM glucose (N = 6). (C) ATPLite assay in 25 mM glucose (N = 16). Scale bar = 100um.

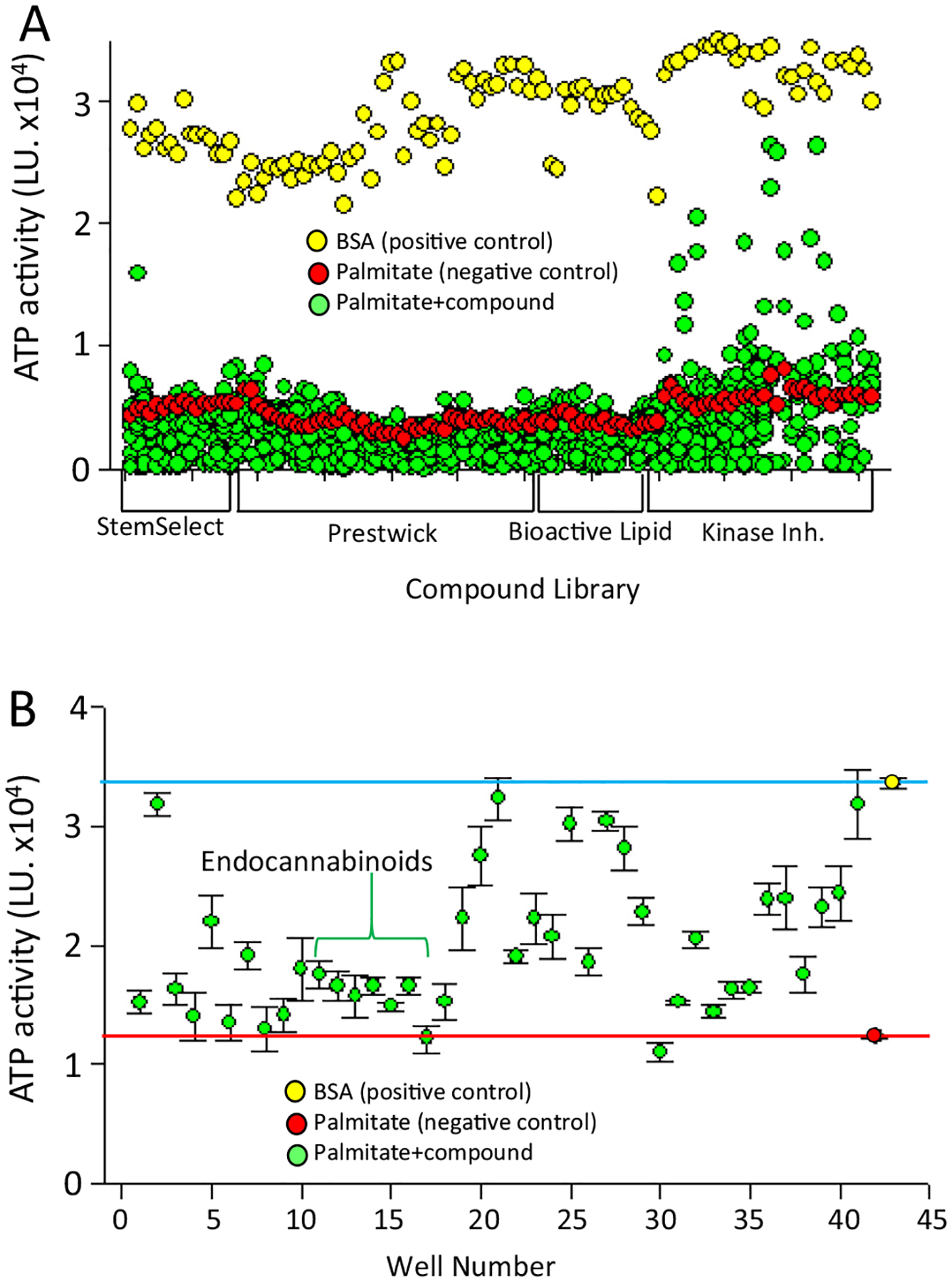

3.2. High-throughput screen for compounds that prevent palmitate-induced INS1 cell death

Four compound libraries comprising 2025 compounds (Table 1) were screened in 384 well plates. Hits were defined as those that had ATPLite activity greater than 2-fold above the mean of the negative controls on each plate (Fig. 2A). For initial confirmation of the hits, 40 positive compounds (Table 2) were cherry-picked from the screening libraries and were rescreened in quadruplicate (Fig. 2B). 35 of 40 hits replicated when rescreened using the primary assay based on ATPLite (Fig. 2B).

Table 1.

Libraries screened.

| Library | Vendor | # of compounds |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitors | EMD (Massachusetts, USA) | 327 |

| StemSelect | EMD (Massachusetts, USA) | 303 |

| Bioactive lipid collection | Enzo Life Science (New York, USA) | 195 |

| Prestwick chem library | Prestwick (San Diego, USA) | 1200 |

Fig. 2.

High-throughput screen. 2025 compounds from the libraries listed in Table 1 were incubated for 2 days with INS1 cells, followed by determination of ATP level by ATPLite assay. (A) Primary assay. Each dot represents the data from a single compound. The positive control was cells treated with fatty acid free BSA (0.9%) (yellow dots, N = 112). The negative control was cells treated with 0.75 mM palmitate plus DMSO (red dots, N = 112). For the experimental group, cells were treated with 0.75 mM palmitate plus compound (10uM) for 2 days, after which the ATP level was measured. (B) Primary confirmatory assay. 40 hits from A were tested in quadruplicate using the primary assay. The red line is the mean of the negative control (red dot) and the blue line is the mean of the positive control (yellow dot). Green dots represent the mean of the value from each compound (0.75 mM palmitate + 10uM of each compound, N = 4). Error bars are standard deviation.

Table 2.

Confirmed hits. Primary assay hits that were confirmed as positive in a rescreen of the primary assay performed in quadruplicate.

| Name | Compound Name | Putative Target | CAS# | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | EMD StemSelect | HSP90 Inhibitor, | HSP90 | 171009-07-7 |

| 2 | EMD StemSelect | GSK-3 Inhibitor IX | GSK-3 | 667463-62-9 |

| 3 | Prestwick 2015 | Pioglitazone | PPARg | 111025-46-8 |

| 4 | Prestwick 2015 | Clofibrate | PPARa | 637-07-0 |

| 5 | Prestwick 2015 | Lynestrenol | Progesterone receptor | 52-76-6 |

| 6 | Prestwick 2015 | Pirenzepine dihydrochloride | M1 muscarinic acetylcholine rec. | 29868-97-1 |

| 7 | Prestwick 2015 | Nisoldipine | 1,4-dihydropyridine Ca++ channel | 63675-72-9 |

| 8 | Prestwick 2015 | 2-Aminobenzenesulfonamide | Carbonic anhydrase | 3306-62-5 |

| 9 | Prestwick 2015 | Rifapentine | Bacterial RNA polymerase | 61379-65-5 |

| 10 | Prestwick Drugs | Talampicillin hydrochloride | DD-transpeptidase | 39878-70-1 |

| 11 | Bioactive Lipids | Anandamide (20:4, n-6) | Cannabinoid receptor | 94421-68-8 |

| 12 | Bioactive Lipids | Anandamide (20:3,n-6) | Cannabinoid receptor | |

| 13 | Bioactive Lipids | Anandamide (22:4,n-6) | Cannabinoid receptor | |

| 14 | Bioactive Lipids | Mead ethanolamide | Cannabinoid receptor | 169232-04-6 |

| 15 | Bioactive Lipids | (R)-Methanandamide | Cannabinoid receptor | 157182-49-5 |

| 16 | Bioactive Lipids | Arachidonamide | Cannabinoid receptor | 85146-53-8 |

| 17 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Alsterpaullone | CDK1, CDK5, Cyclin B | 237430-03-4 |

| 18 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Aloisine, RP106 | GSK3b | 496864-15-4 |

| 19 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Kenpaullone | CDK1, CDK2, CDK5, GSK3b | 142273-20-9 |

| 20 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Syk Inhibitor | Syk | 622387-85-3 |

| 21 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Indirubin-3′-oxime | GSK3 | 160807-49-8 |

| 22 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | GSK-3 Inhibitor XIII | GSK3 | 404828-08-6 |

| 23 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Indirubin Derivative E804 | Src, Cdc2, Cdk2 | 854171-35-0 |

| 24 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | JNK Inhibitor V | JNK | 345987-15-7 |

| 25 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | GSK-3b Inhibitor VIII | GSK3b | 487021-52-3 |

| 26 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | GSK-3 Inhibitor IX | GSK3 | 667463-62-9 |

| 27 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | GSK-3 Inhibitor X | GSK3 | 740841-15-0 |

| 28 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | GSK-3b Inhibitor XI | GSK3b | 626604-39-5 |

| 29 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | JAK Inhibitor I | JAK | 457081-03-7 |

| 30 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Tyrphostin AG 879 | TrkA, HER-2 | 148741-30-4 |

| 31 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | YM-201636 | PIKfyve | 371942-69-7 |

| 32 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | AS605240 | PI3-Kg | 648450-29-7 |

| 33 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | SMI-4a | PIM1/2 | 327033-36-3 |

| 34 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | PIM1/2 Kinase Inhibitor VI | PIM1/2 | 587852-28-6 |

| 35 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Chk2 Inhibitor | Chk2 | 724708-21-8 |

| 36 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Indirubin-3′-monoxime, 5-Iodo- | GSK3b, CDK1, CDK5 | 331467-03-9 |

| 37 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | IRAK-1/4 Inhibitor I | IRAK-1/4 | 509093-47-4 |

| 38 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | Syk Inhibitor IV, BAY 61-3606 | Syk | 732938-37-8 |

| 39 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | SU9516 | CDK2 | 666837-93-0 |

| 40 | EMD Kinase Inhibitor | 1-Azakenpaullone | GSK3b | 676596-65-9 |

The compounds from the Prestwick and StemSelect libraries did not demonstrate any obvious pattern, with diverse structures and mechanisms of action being represented among the hits. The Bioactive Lipids library was remarkable in that there was a cluster of endocannabinoid hits. The majority of the hits in the screen came from the kinase inhibitor library.

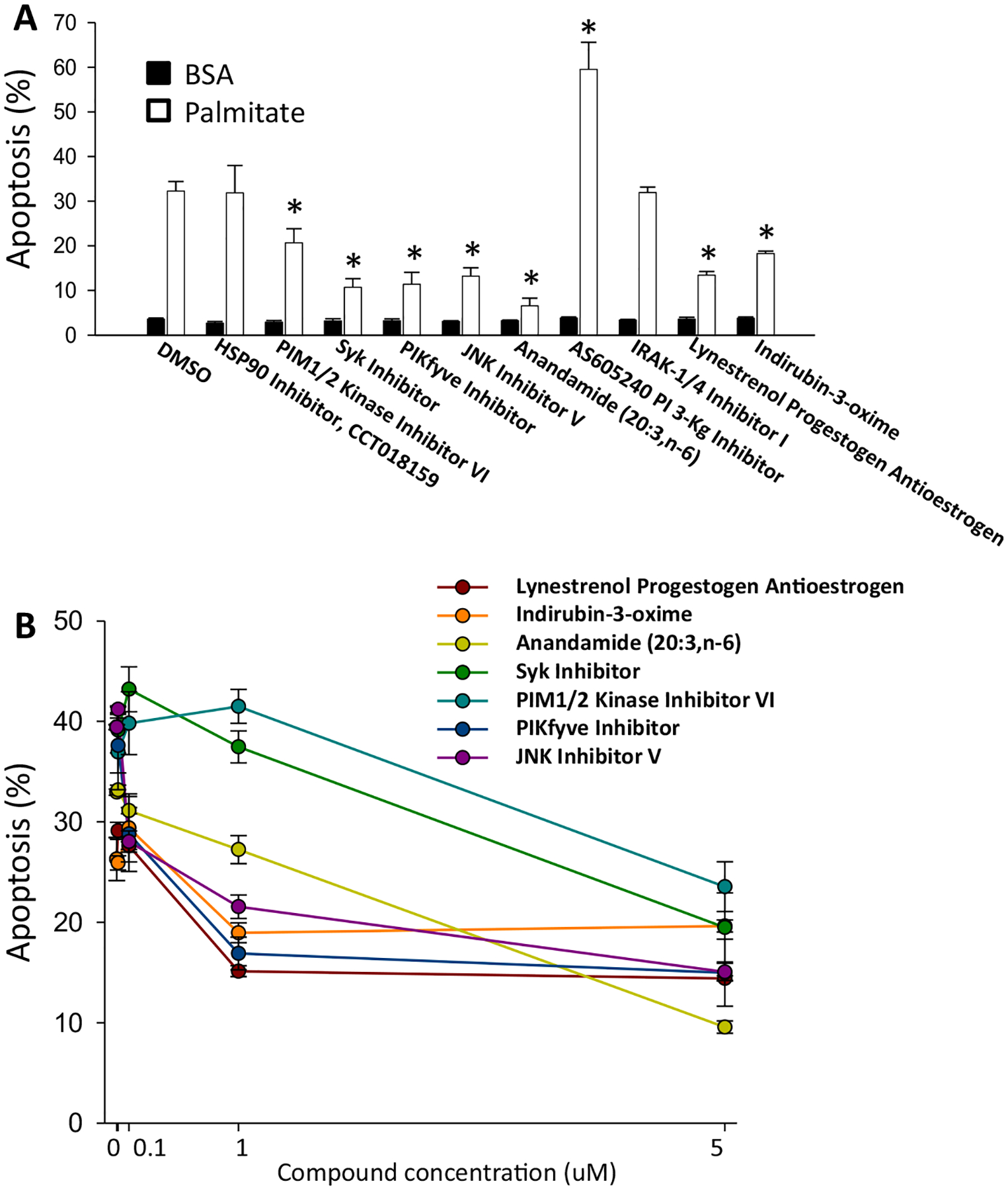

3.3. Secondary assays

Ten interesting compounds (Fig. 3A) from the 35 that passed primary confirmation were selected for secondary assays in INS1E cells based on the presence of at least one of the following criteria: 1. Putative targets of the compound were expressed in FACS-purified primary rat β-cells and human islets using RPKM >0.5 as a cutoff [27,28]; 2. Targets were involved in pathways of known or potential biological relevance to β-cell survival or function. Because the ATPLite assay does not directly measure apoptosis, it was important to use a more specific secondary assay. Thus, selected compounds were tested in an assay in which apoptosis was specifically assessed by staining with Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide as done previously [29]. Seven of the ten compounds tested inhibited apoptosis in that assay (Fig. 3A). The seven most active were selected for further study. They were examined for dose-responsive inhibition of apoptosis, with the finding that all exhibited dose-responsive inhibition of apoptosis (Fig. 3B). Substantial inhibition of apoptosis was achieved in some cases -up to 3.5-fold- but in no case was the inhibition complete, i.e., providing complete protection against palmitate-induced cell death.

Fig. 3.

Effect of selected HTS compounds on palmitate-induced beta-cell death. Apoptosis in INS-1E cells was measured using the Hoechst 33342 and propidium iodide assay (A) Cells were cultured for 1 day in medium containing 11 mM glucose, 1% FBS, 0.75% fatty acid-free BSA with 0.5 mM palmitate and 5 μM of compounds (N = 3). Black bar is BSA only and white bar is palmitate treated, with or without the addition of putative protective compounds. (B) Dose-response of protective compounds. The vehicle was DMSO. *p < 0.05 against palmitate-treated cells.

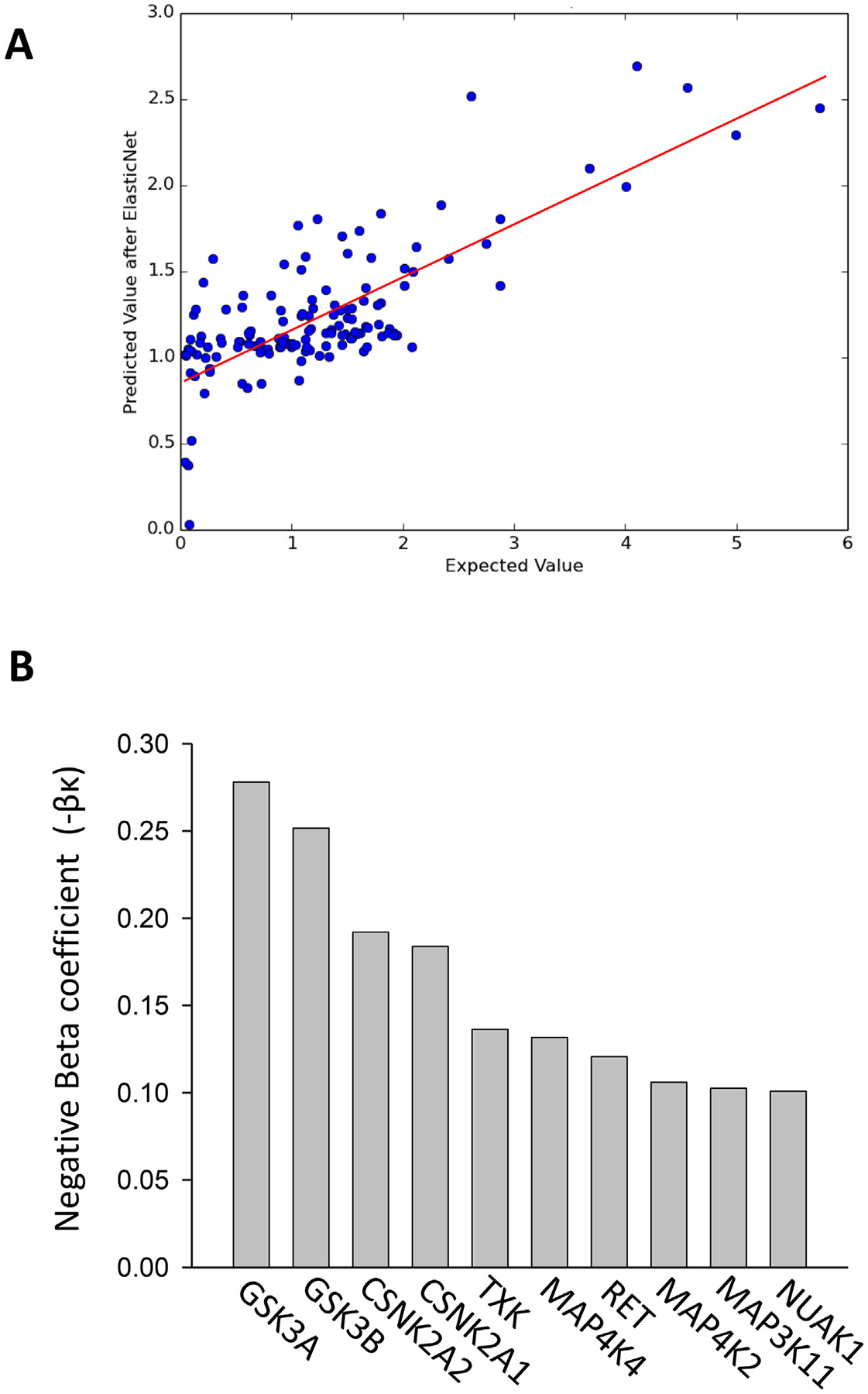

3.4. Bioinformatics identify the candidate targets of hits from the Kinase Inhibitor library

Examining the putative targets of the reproducibly positive compounds revealed that in virtually every case in which multiple compounds from the libraries that were screened were directed against the same putative target, only a subset of the compounds against a particular target were positive. This was particularly notable for the kinase inhibitor hits. For example, only 10 of 27 screened compounds that inhibited GSK3 were hits. This suggested that the activity of the compounds may have been due to activity on targets other than the putative target of the compounds.

To determine the identity of the targets of the positive compounds that were responsible for inhibition of lipotoxicity, we used a bioinformatics approach called the Kinase Inhibitors Elastic Net (KIEN) method [10]. This method combines data from a screen with data on off-target effects of kinase inhibitors to identify candidates for the actual kinase that was inhibited by screening hits. Specifically, the method integrates information contained in drug-kinase profiling, namely the residual catalytic activity Ak,i of the kinase k after interacting with compound i [30], with the cell viability vi after in vitro treatment with the same compound. The cell response to drugs from the screen was used to build a linear regression model as vi = β0 + β1A1,i + β2A2,i + ⋯ + βpAp,i where p = 291 was the total number of kinases, i = 1, …, 139 identified the compound screened, and the residual catalytic activities Ak,i were treated as predictors of the cell responses vi. Thus, two different types of data were integrated: kinase profiling data obtained through enzymatic assays that probe directly the interaction between drug and kinases, and in vitro cell response data that is the result of complex signaling that involves many pathways downstream of the affected kinases.

To keep the set of kinases to a minimum, we used the elastic net regression method, which modifies the least square minimization by imposing a penalty on the regression coefficients [31]. For each kinase k, the regression provided a coefficient score βk that was interpreted as a measure of the sensitivity of cells to alterations in the activity of that kinase. The elastic net screening selected 247 kinases as predictors, forcing the remaining 44 to have βk = 0. A negative beta coefficient means that inhibition of that kinase is associated with increased cell survival in the experiment, which is the effect we are interested in. The elastic net algorithm is designed to find the optimal balance between fitting the data and using the smallest set of kinases as variables. The regression had an R2 = 0.57 (Fig. 4A). The top 10 relevant kinases according to the elastic net method are shown in Fig. 4B.

Fig. 4.

Bioinformatic analysis of kinase inhibitor screen. (A) Comparison between the cell viability obtained using the elastic net regression and the actual values vi measured in the experiment. The coefficient of determination R2 = 0.57 is the square of the Pearson correlation between the and the vi. (B) Top 10 relevant kinases determined by the elastic net method.

3.5. siRNA as an orthogonal approach to target validation

Given that small molecule kinase inhibitors are promiscuous, it was important to use an independent assay to verify target identity. For that purpose, we employed siRNAs as an orthogonal approach to determine whether the putative targets of the small molecules were valid. While siRNAs against a specific target mRNA are known to have a significant number of off-target effects [32], those effects are due to an entirely different mechanism than those of small molecule kinase inhibitors. Thus, if both the small molecule and an siRNA against the same putative target are active, this provides a high degree of assurance that the target is valid.

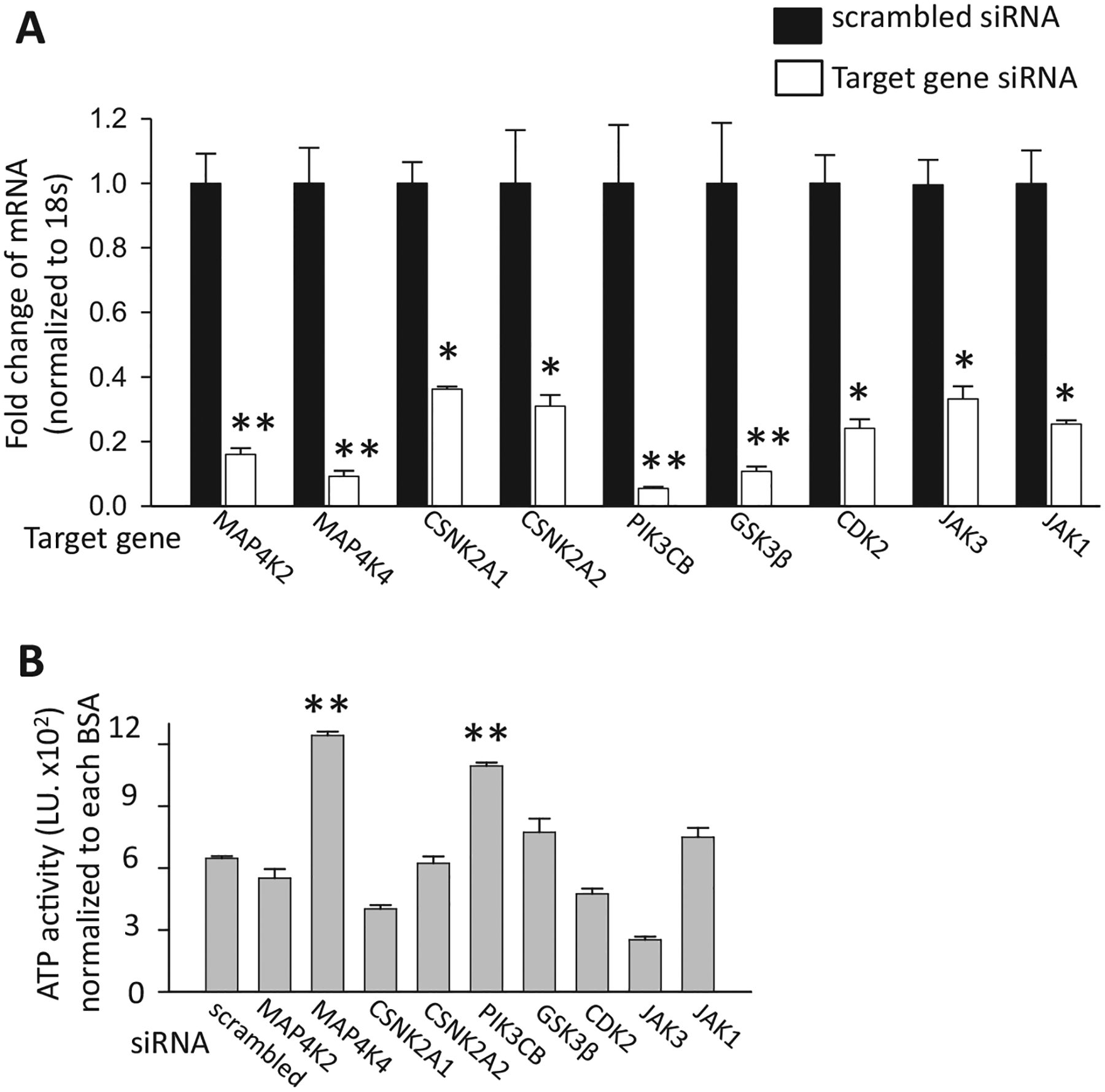

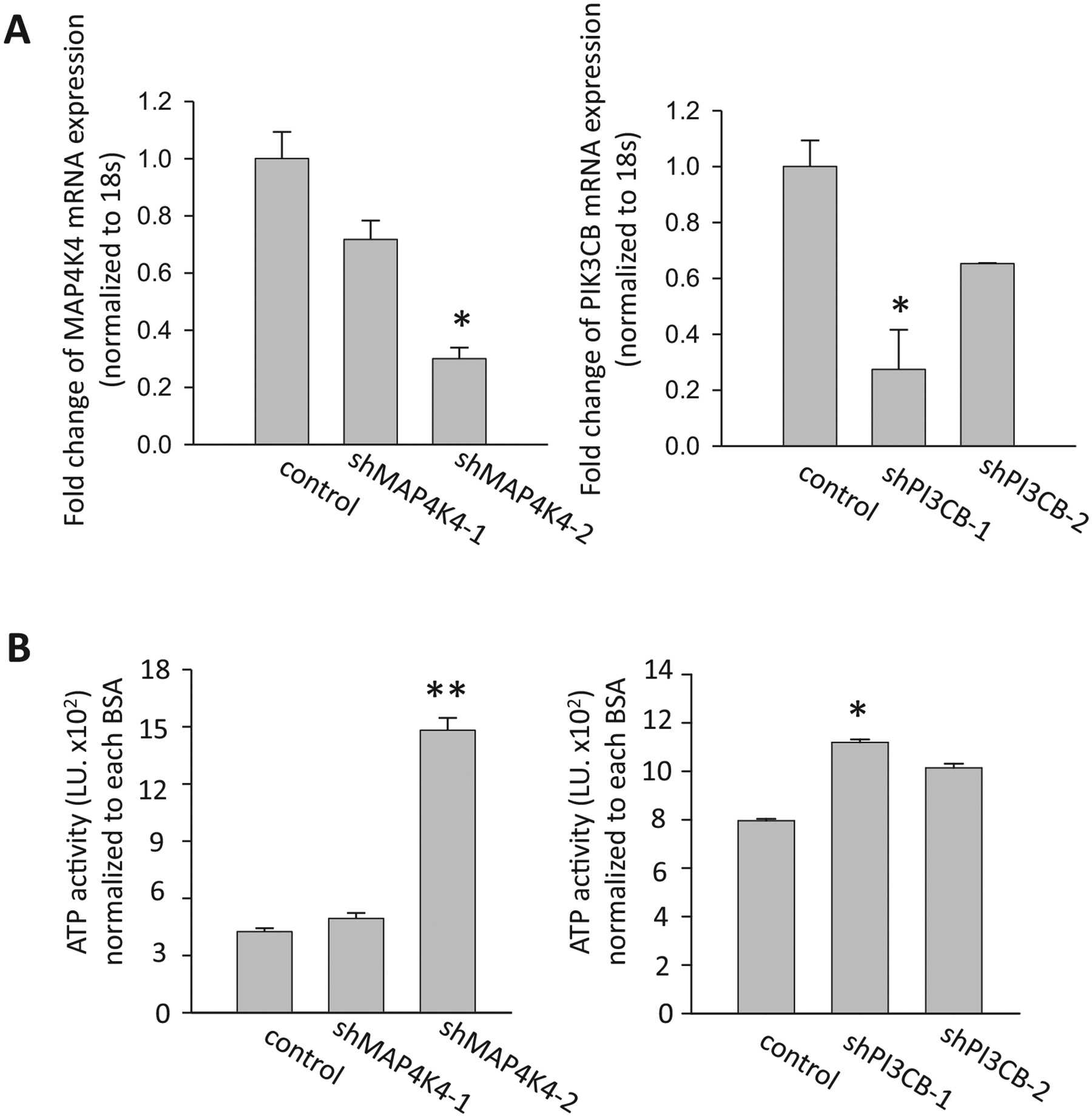

A subset of the putative targets of the small molecule inhibitors, as well as targets identified by the bioinformatics approach, were inhibited using siRNAs. Each siRNA was validated by qPCR (Fig. 5A) Of the targets studied, only siRNA-mediated inhibition of MAP4K4 and PIK3CB repressed palmitate induced cell death in the ATPLite assay (Fig. 5B). To increase the level of confidence further, we employed lentivirally-encoded shRNAs, which confirmed the data from the siRNA studies (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

siRNA to target validation. (A) siRNAs were validated by qPCR. T6PNE cells transfected with target gene or scrambled siRNA were harvested for RNA after 2 days (N = 5 technical replicates). (B) Candidate target gene siRNAs were transfected into human T6PNE cells for 2 days followed by treatment with BSA or palmitate (0.25 mM) for 2 days (N = 4). ATP activity of palmitate treated siRNA is normalized to that of the same siRNA treated with BSA. *p < 0.005, **p < 0.001against scrambled siRNA control. Error bars are standard error.

Fig. 6.

shRNA-mediated inhibition of MAP4K4 and PI3CB. (A) T6PNE cells were infected with lentiviral vectors encoding two different shRNAs to MAP4K4 and two shRNAs to PIK3CB. Gene expression was measured by qPCR to determine effects of the shRNAs on MAP4K4 and PIK3CB mRNA levels. (B) Clones of cells expressing the indicated shRNA were treated with BSA or palmitate (0.25 mM) for 2 days, followed by measurement of ATP activity. The ATP activity for each experiment with an shRNA clone was normalized to the same clone treated with BSA alone (N = 4). *p < 0.05, *p < 0.0001 against control. Error bars are standard error.

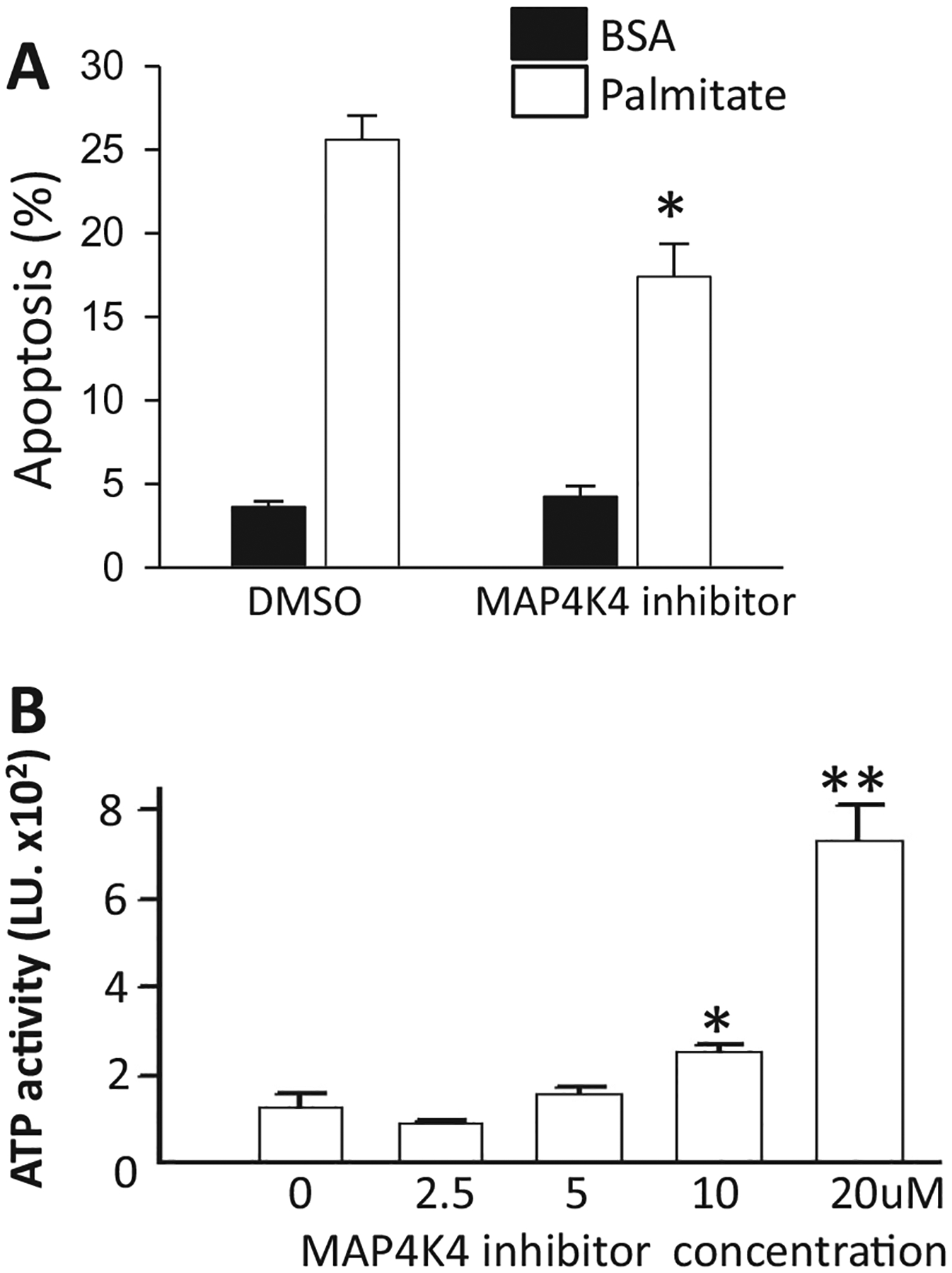

3.6. Small molecule inhibitor of MAP4K4

MAP4K4 was identified as a potential mediator of palmitate-induced apoptosis through the bioinformatics approach, using data from the HTS. While the siRNA and shRNA studies indicated that this identification was accurate, we had not tested any small molecule MAP4K4 inhibitors for their ability to inhibit palmitate-induced apoptosis. Unfortunately, no commercially available compounds that exhibited selectivity for MAP4K4 were available. Therefore, we synthesized compound 1 (6-(2-Fluoropyridin-4-yl) pyrido[3,2-d]pyrimidin-4-amine) [33] which exhibits substantial selectively for MAP4K4 and excellent potency (IC50 = 17nM). Compound 1 inhibited palmitate-induced apoptosis in INS-1E (Fig. 7A) and T6PNE [14] cells (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Effect of MAP4K4 inhibitor. (A) Apoptosis in INS-1E cells pre-treated for 2 h with 10 μM MAP4K4 inhibitor and treated for 1 day with 0.5 mM palmitate plus the MAP4K4 inhibitor (N = 5). (B) Dose response with MAP4K4 inhibitors in human T6PNE cells treated with 0.25 mM palmitate (N = 4). ATP activity measured after 48 h. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.001 against palmitate-treated cells. Error bars are standard error.

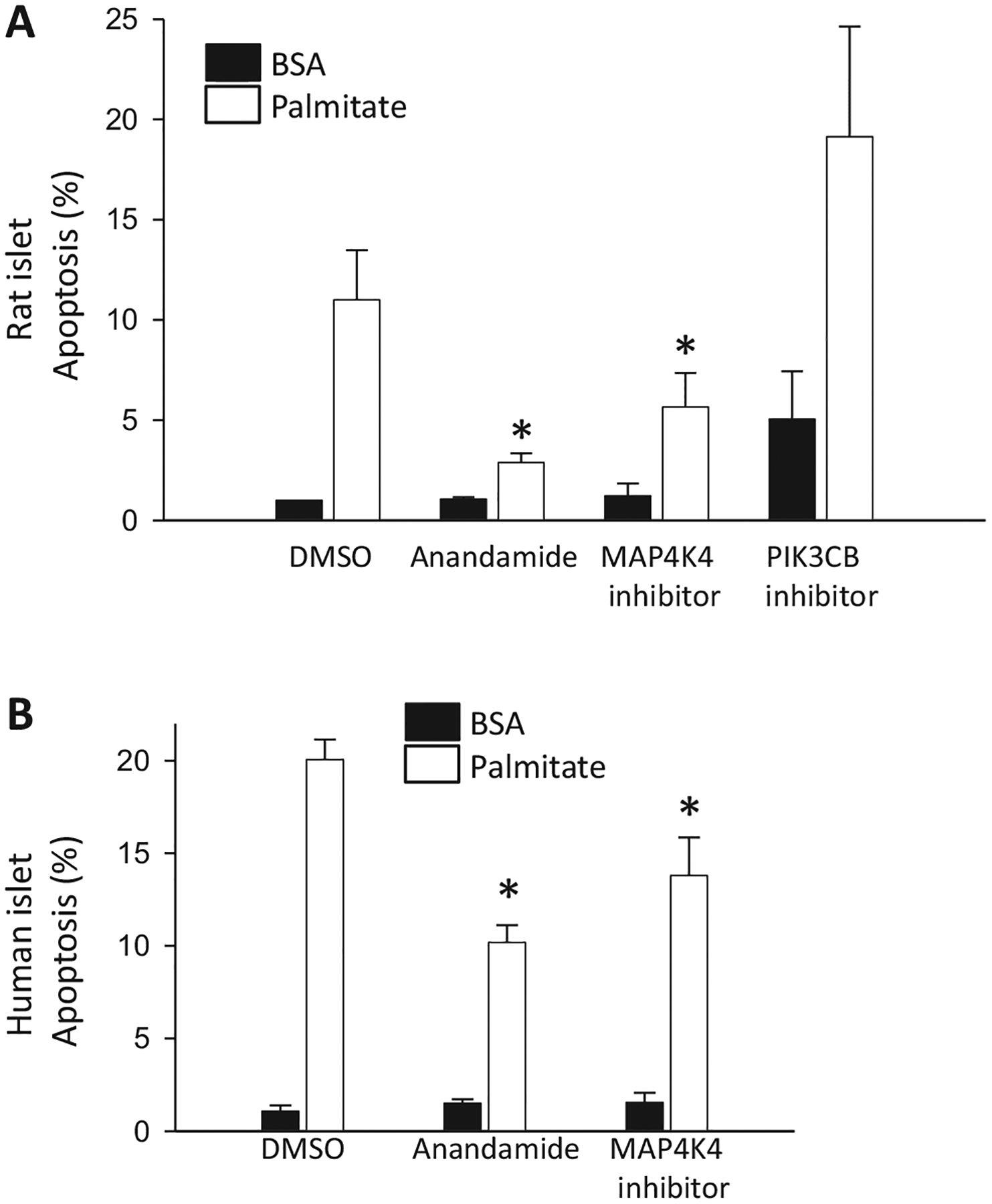

3.7. Effect of target inhibition by small molecules on palmitate-induced apoptosis in primary islets

Having demonstrated that inhibitors of MAP4K4 and PI3CB, as well as endocannabinoids, were cytoprotective in palmitate-mediated apoptosis in cell lines, we proceeded to extend our studies to primary islets. In rat islets, anandamide and the MAP4K4 inhibitor (compound 1) led to decreased apoptosis (Fig. 8A). Small molecule inhibition of PIK3CB actually caused increased apoptosis in rat islets even in the absence of palmitate (Fig. 8A). Thus, anandamide and the MAP4K4 inhibitor were tested in primary human islets, where both partially inhibited palmitate-induced apoptosis (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Apoptosis in primary islets. (A) Apoptosis in primary rat islets cultured for 3 days in medium containing 10 mM glucose, no FBS, 0.75% fatty acid-free BSA with 0.5 mM palmitate with DMSO or 5 μM anandamide, MAP4K4 inhibitor, PIK3CB inhibitor (N = 3). (B) Cell death in human islets cultured for 3 days in medium containing 6.1 mM glucose, 1% charcoal absorbed BSA with 0.5 mM palmitate and DMSO or 5 μM anandamide, MAP4K4 inhibitor (N = 3–4). The vehicle was DMSO. *p < 0.05 against palmitate-treated cells. Error bars are standard error.

4. Discussion

Despite much effort, our understanding of the mechanisms by which fatty acids induce pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and death is quite limited, with many pathways being implicated [27], but none having been definitively proven or developed into an effective therapy [34]. High-throughput phenotypic screening is attractive as an unbiased approach to discovering new targets that modulate biological processes. Here, we screened small molecule libraries containing fairly well-characterized compounds and identified a number that inhibited palmitate-induced cell death. It is important to note that the primary assay was based on a rat insulinoma cell line. Hits from the cell line assay were pursued in primary islets, including human, and most but not all, e.g., the PIK3CB inhibitor, confirmed.

Most of the hits from our screen came from a library of kinase inhibitors. Unfortunately for efforts to use small molecules as probes to study the function of specific molecular targets, many if not most small molecules act on multiple targets [35]. This is particularly true for kinase inhibitors, the vast majority of which interact with the ATP binding pocket [30,36]. To deal with the extreme promiscuity of kinase inhibitors and identify the true targets responsible for inhibition of lipotoxicity, we employed a bioinformatics approach. The KIEN method quantifies the role of multiple kinases in a biological process [10], and thus allowed us to find hidden targets because not all kinases are the principal targets of any of the tested inhibitors. In this study, we used it to identify MAP4K4 as an important single kinase in β-cell lipotoxicity. However, the method could also be extended to guide a combinatorial approach in which multiple kinases are inhibited by the amount suggested by the model. This could be approximated by an optimally designed combination of multiple kinase inhibitors under a model in which lipotoxicity is mediated by multiple signaling pathways that each involve distinct kinases.

Of the multiple kinases that were targeted by initial hits in the assay, MAP4K4 passed the multiple layers of confirmatory assays, including studies with human islets. MAP4K4 is widely expressed and plays a role in multiple biological processes, including inflammation [37], cellular proliferation [38], and metabolism [39]. In diabetes, MAP4K4 mRNA and protein expression was reported to be increased in islets from diabetic db/db mice [40]. With respect to human diabetes, it has been identified through GWAS studies as being associated with type 2 diabetes [41]. Studies on its role in cell death are contradictory, with reports of pro-apoptotic [42] as well as anti-apoptotic [38] effects in cancer cells. In β-cells MAP4K4 silencing attenuated detrimental effects of TNF-α on insulin secretion and signaling [43]. In our studies of islet cell lines and primary rat and human islets, inhibition of MAP4K4 with pharmacological inhibitors or by siRNA/shRNA led to increased survival, consistent with a pro-apoptotic role for MAP4K4 in β-cells.

Apart from the kinase inhibitors, the most striking result was that multiple cannabinoid receptor agonists were positive in the assay. Consistent with an on-target effect, anandamide (18:2,n-6), an inactive anandamide analog, was inactive. However, N-arachidonylglycine, an active anandamide analog that is resistant to cleavage by fatty acid amide hydrolase, was not a hit. This is in keeping with an earlier report on β-cell cytoprotection from lipotoxicity with oleoylethanolamide, which acted indirectly to attenuate palmitate toxicity through its internalization and hydrolysis by fatty acid amide hydrolase to release oleate [44], a known antagonist of palmitate toxicity [15,45]. Taken together, these results suggest that the true active compounds in the assay may be metabolites that act on targets other than cannabinoid receptors. This is supported by the fact that, while endocannabinoid receptors have been purported to be present in the pancreas [46], examination of recent RNA-Seq data finds that these receptors are not detectable or expressed at a very low level in primary human and rat islets or β-cells [27,28,47]. Thus, the primary target of the cannabinoid receptor agonists that is responsible for their ability to inhibit lipotoxicity remains unclear but there are many possible candidates, including free fatty acid receptors.

A drawback of this and all other studies of β-cell lipotoxicity is that none of the compounds led to complete inhibition of apoptosis. While many compounds and targets have been studied for effects on lipotoxicity, in no case has a single target been found to be sufficient to completely inhibit fatty acid-induced cell death [9,34]. The biological effects of fatty acids are complex, with multiple downstream pathways likely being responsible for their toxic effect on cells. Thus, no single intervention may be sufficient to completely inhibit the ability of fatty acids to induce cell death. Ultimately, protection of β-cells from lipotoxicity is likely to require a multi-faceted approach. The bioinformatics approach that we used here is well suited for the identification of candidate combinations, which would require additional testing in a high-throughput assay such as that used here.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Sanford Children’s Health Research Center, BetaBat (in the Framework Program 7 of the European Union) and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, project T2DSystems, under grant agreement No 667191. We thank Dr. Pedro Aza-Blanc and the SBP Functional Genomics CORE for their invaluable help with the siRNA and shRNA studies, and the SBP CPCCG Screening Center for high throughput screening. The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations:

- MAP4K4

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase kinase 4

- PIK3CB

phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit beta

- KIEN

Kinase Inhibitors Elastic Net

- GWAS

genome-wide association study

References

- [1].Buteau J, El-Assaad W, Rhodes CJ, Rosenberg L, Joly E, Prentki M, Glucagon-like peptide-1 prevents beta cell glucolipotoxicity, Diabetologia 47 (5) (2004) 806–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Joseph JW, Koshkin V, Saleh MC, Sivitz WI, Zhang CY, Lowell BB, et al. , Free fatty acid-induced beta-cell defects are dependent on uncoupling protein 2 expression, J Biol Chem 279 (49) (2004) 51049–51056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen J, Jeppesen PB, Nordentoft I, Hermansen K, Stevioside counteracts beta-cell lipotoxicity without affecting acetyl CoA carboxylase, Rev Diabet Stud 3 (4) (2006) 178–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wang W, Zhang D, Zhao H, Chen Y, Liu Y, Cao C, et al. , Ghrelin inhibits cell apoptosis induced by lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cell line, Regul Pept 161 (1–3) (2010) 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Green CD, Olson LK, Modulation of palmitate-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in pancreatic beta-cells by stearoyl-CoA desaturase and Elovl6, Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300 (4) (2011) E640–E649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ahowesso C, Black PN, Saini N, Montefusco D, Chekal J, Malosh C, et al. , Chemical inhibition of fatty acid absorption and cellular uptake limits lipotoxic cell death, Biochem Pharmacol 98 (1) (2015) 167–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chick WL, Warren S, Chute RN, Like AA, Lauris V, Kitchen KC, A transplantable insulinoma in the rat, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 74 (1977) 628–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB, Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines, Endocrinology 130 (1992) 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cunha DA, Gurzov EN, Naamane N, Ortis F, Cardozo AK, Bugliani M, et al. , JunB protects beta-cells from lipotoxicity via the XBP1-AKT pathway, Cell Death Differ 21 (8) (2014) 1313–1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Tran TP, Ong E, Hodges AP, Paternostro G, Piermarocchi C, Prediction of kinase inhibitor response using activity profiling, in vitro screening, and elastic net regression, BMC Syst Biol 8 (2014) 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Hohmeier HE, Mulder H, Chen G, Henkel-Rieger R, Prentki M, Newgard CB, Isolation of INS-1-derived cell lines with robust ATP-sensitive K+ channel-dependent and -independent glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, Diabetes 49 (3) (2000) 424–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB, Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines, Endocrinology 130 (1) (1992) 167–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Oliveira AF, Cunha DA, Ladriere L, Igoillo-Esteve M, Bugliani M, Marchetti P, et al. , In vitro use of free fatty acids bound to albumin: A comparison of protocols, Biotechniques 58 (5) (2015) 228–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kiselyuk A, Farber-Katz S, Cohen T, Lee SH, Geron I, Azimi B, et al. , Phenothiazine neuroleptics signal to the human insulin promoter as revealed by a novel high-throughput screen, J Biomol Screen 15 (6) (2010) 663–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Cunha DA, Hekerman P, Ladriere L, Bazarra-Castro A, Ortis F, Wakeham MC, et al. , Initiation and execution of lipotoxic ER stress in pancreatic beta-cells, J Cell Sci 121 (Pt 14) (2008) 2308–2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rasschaert J, Ladriere L, Urbain M, Dogusan Z, Katabua B, Sato S, et al. , Toll-like receptor 3 and STAT-1 contribute to double-stranded RNA+ interferon-gamma-induced apoptosis in primary pancreatic beta-cells, J Biol Chem 280 (40) (2005) 33984–33991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hoorens A, Van de Casteele M, Kloppel G, Pipeleers D, Glucose promotes survival of rat pancreatic beta cells by activating synthesis of proteins which suppress a constitutive apoptotic program, J Clin Invest 98 (7) (1996) 1568–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Gurzov EN, Germano CM, Cunha DA, Ortis F, Vanderwinden JM, Marchetti P, et al. , P53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) activation contributes to pancreatic beta-cell apoptosis induced by proinflammatory cytokines and endoplasmic reticulum stress, J Biol Chem 285 (26) (2010) 19910–19920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Allagnat F, Cunha D, Moore F, Vanderwinden JM, Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK, Mcl-1 downregulation by pro-inflammatory cytokines and palmitate is an early event contributing to beta-cell apoptosis, Cell Death Differ 18 (2) (2011) 328–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Moore F, Santin I, Nogueira TC, Gurzov EN, Marselli L, Marchetti P, et al. , The transcription factor C/EBP delta has anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory roles in pancreatic beta cells, PLoS One 7 (2) (2012) e31062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ling Z, Hannaert JC, Pipeleers D, Effect of nutrients, hormones and serum on survival of rat islet beta cells in culture, Diabetologia 37 (1) (1994) 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eizirik DL, Korbutt GS, Hellerstrom C, Prolonged exposure of human pancreatic islets to high glucose concentrations in vitro impairs the beta-cell function, J Clin Invest 90 (4) (1992) 1263–1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Igoillo-Esteve M, Marselli L, Cunha DA, Ladriere L, Ortis F, Grieco FA, et al. , Palmitate induces a pro-inflammatory response in human pancreatic islets that mimics CCL2 expression by beta cells in type 2 diabetes, Diabetologia 53 (7) (2010) 1395–1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Miret S, De Groene EM, Klaffke W, Comparison of in vitro assays of cellular toxicity in the human hepatic cell line HepG2, J Biomol Screen 11 (2) (2006) 184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].El-Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot ML, Nolan C, Roduit R, Hardy S, et al. , Saturated fatty acids synergize with elevated glucose to cause pancreatic beta-cell death, Endocrinology 144 (9) (2003) 4154–4163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR, A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays, J Biomol Screen 4 (2) (1999) 67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Cnop M, Abdulkarim B, Bottu G, Cunha DA, Igoillo-Esteve M, Masini M, et al. , RNA-sequencing identifies dysregulation of the human pancreatic islet transcriptome by the saturated fatty acid palmitate, Diabetes (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Villate O, Turatsinze JV, Mascali LG, Grieco FA, Nogueira TC, Cunha DA, et al. , Nova1 is a master regulator of alternative splicing in pancreatic beta cells, Nucleic Acids Res 42 (18) (2014) 11818–11830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Cnop M, Ladriere L, Hekerman P, Ortis F, Cardozo AK, Dogusan Z, et al. , Selective inhibition of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha dephosphorylation potentiates fatty acid-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and causes pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction and apoptosis, J Biol Chem 282 (6) (2007) 3989–3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Anastassiadis T, Deacon SW, Devarajan K, Ma H, Peterson JR, Comprehensive assay of kinase catalytic activity reveals features of kinase inhibitor selectivity, Nat Biotechnol 29 (11) (2011) 1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Zou H, Hastie T, Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net, J R Stat Soc 67 (2) (2005) 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jackson AL, Burchard J, Schelter J, Chau BN, Cleary M, Lim L, et al. , Widespread siRNA “off-target” transcript silencing mediated by seed region sequence complementarity, RNA 12 (7) (2006) 1179–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Crawford TD, Ndubaku CO, Chen H, Boggs JW, Bravo BJ, Delatorre K, et al. , Discovery of selective 4-Amino-pyridopyrimidine inhibitors of MAP4K4 using fragment-based lead identification and optimization, J Med Chem 57 (8) (2014) 3484–3493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Janikiewicz J, Hanzelka K, Kozinski K, Kolczynska K, Dobrzyn A, Islet beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes–Within the network of toxic lipids, Biochem Biophys Res Commun 460 (3) (2015) 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Hu Y, Bajorath J, Compound promiscuity: what can we learn from current data? Drug Discov Today 18 (13–14) (2013) 644–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hantschel O, Unexpected off-targets and paradoxical pathway activation by kinase inhibitors, ACS Chem Biol 10 (1) (2015) 234–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Aouadi M, Tesz GJ, Nicoloro SM, Wang M, Chouinard M, Soto E, et al. , Orally delivered siRNA targeting macrophage Map4k4 suppresses systemic inflammation, Nature 458 (7242) (2009) 1180–1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Liu YF, Qu GQ, Lu YM, Kong WM, Liu Y, Chen WX, et al. , Silencing of MAP4K4 by short hairpin RNA suppresses proliferation, induces G1 cell cycle arrest and induces apoptosis in gastric cancer cells, Mol Med Rep 13 (1) (2016) 41–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Virbasius JV, Czech MP, Map4k4 signaling nodes in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases, Trends Endocrinol Metab 27 (7) (2016) 484–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Zhao X, Mohan R, Ozcan S, Tang X, MicroRNA-30d induces insulin transcription factor MafA and insulin production by targeting mitogen-activated protein 4 kinase 4 (MAP4K4) in pancreatic beta-cells, J Biol Chem 287 (37) (2012) 31155–31164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Sartorius T, Staiger H, Ketterer C, Heni M, Machicao F, Guilherme A, et al. , Association of common genetic variants in the MAP4K4 locus with prediabetic traits in humans, PLoS One 7 (10) (2012) e47647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chen S, Li X, Lu D, Xu Y, Mou W, Wang L, et al. , SOX2 regulates apoptosis through MAP4K4-survivin signaling pathway in human lung cancer cells, Carcinogenesis 35 (3) (2014) 613–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Bouzakri K, Ribaux P, Halban PA, Silencing mitogen-activated protein 4 kinase 4 (MAP4K4) protects beta cells from tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced decrease of IRS-2 and inhibition of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, J Biol Chem 284 (41) (2009) 27892–27898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Stone VM, Dhayal S, Smith DM, Lenaghan C, Brocklehurst KJ, Morgan NG, The cytoprotective effects of oleoylethanolamide in insulin-secreting cells do not require activation of GPR119, Br J Pharmacol 165 (8) (2012) 2758–2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Cnop M, Hannaert JC, Hoorens A, Eizirik DL, Pipeleers DG, Inverse relationship between cytotoxicity of free fatty acids in pancreatic islet cells and cellular triglyceride accumulation, Diabetes 50 (8) (2001) 1771–1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Doyle ME, The role of the endocannabinoid system in islet biology, Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 18 (2) (2011) 153–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Segerstolpe A, Palasantza A, Eliasson P, Andersson EM, Andreasson AC, Sun X, et al. , Single-cell transcriptome profiling of human pancreatic islets in health and type 2 diabetes, Cell Metab 24 (4) (2016) 593–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]