Abstract

The conversion of O-methylsterigmatocystin (OMST) and dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin to aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2 requires a cytochrome P-450 type of oxidoreductase activity. ordA, a gene adjacent to the omtA gene, was identified in the aflatoxin-biosynthetic pathway gene cluster by chromosomal walking in Aspergillus parasiticus. The ordA gene was a homolog of the Aspergillus flavus ord1 gene, which is involved in the conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1. Complementation of A. parasiticus SRRC 2043, an OMST-accumulating strain, with the ordA gene restored the ability to produce aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2. The ordA gene placed under the control of the GAL1 promoter converted exogenously supplied OMST to aflatoxin B1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In contrast, the ordA gene homolog in A. parasiticus SRRC 2043, ordA1, was not able to carry out the same conversion in the yeast system. Sequence analysis revealed that the ordA1 gene had three point mutations which resulted in three amino acid changes (His-400→Leu-400, Ala-143→Ser-143, and Ile-528→Tyr-528). Site-directed mutagenesis studies showed that the change of His-400 to Leu-400 resulted in a loss of the monooxygenase activity and that Ala-143 played a significant role in the catalytic conversion. In contrast, Ile-528 was not associated with the enzymatic activity. The involvement of the ordA gene in the synthesis of aflatoxins G1, and G2 in A. parasiticus suggests that enzymes required for the formation of aflatoxins G1 and G2 are not present in A. flavus. The results showed that in addition to the conserved heme-binding and redox reaction domains encoded by ordA, other seemingly domain-unrelated amino acid residues are critical for cytochrome P-450 catalytic activity. The ordA gene has been assigned to a new cytochrome P-450 gene family named CYP64 by The Cytochrome P450 Nomenclature Committee.

Aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2 are toxic and carcinogenic secondary metabolites produced by the filamentous fungi Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Aflatoxin B1 is the most potent hepatocarcinogenic compound known. A. parasiticus produces aflatoxins G1 and G2 in addition to aflatoxins B1 and B2, which distinguishes it from A. flavus, which produces only aflatoxins B1 and B2. These toxins contaminate agricultural commodities and are a potential threat to human health (4, 14, 28). Aflatoxin biosynthesis involves at least 18 enzymatic reactions (for a review see references 4, 14, 15, and 32); advances in the molecular biology of the genus Aspergillus have led to the characterization of several of the genes encoding the enzymes and to identification of aflatoxin-biosynthetic gene clusters in A. flavus and A. parasiticus (36, 41, 46). The uniqueness of aflatoxin biosynthesis is that a polyketide synthase and two fatty acid synthases are required for the formation of the initial anthraquinone and the C-6 side chain, respectively (26, 30, 32). Subsequent steps in the transformation include reduction, oxidative rearrangement, and anthraquinone ring modification (5, 32).

It has been demonstrated that in the late stages of aflatoxin biosynthesis the A. parasiticus omtA gene encodes an S-adenosylmethionine-dependent O-methyltransferase (6, 13, 16, 44, 47) that is required for the conversion of sterigmatocystin (ST) to O-methylsterigmatocystin (OMST) and the conversion of dihydrosterigmatocystin (DHST) to dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin (DHOMST). It has also been shown by feeding studies that aflatoxins B1 and B2 are derived from OMST and DHOMST, respectively (3, 11). It has been postulated that the conversion of OMST to aflatoxins B1 and G1 and the conversion of DHOMST to aflatoxins B2 and G2 (Fig. 1) in A. parasiticus involve an oxidoreductase (3, 5, 11, 12, 43) and require NADPH as a cofactor (3, 5, 11, 43). Recently, it has been demonstrated that the A. flavus ord1 gene, which encodes a putative cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase, is required for the conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 (38). Therefore, there is significant interest in identifying and characterizing the gene(s) and enzyme(s) responsible for conversion of OMST and DHOMST to aflatoxins B1, B2, G1 and G2.

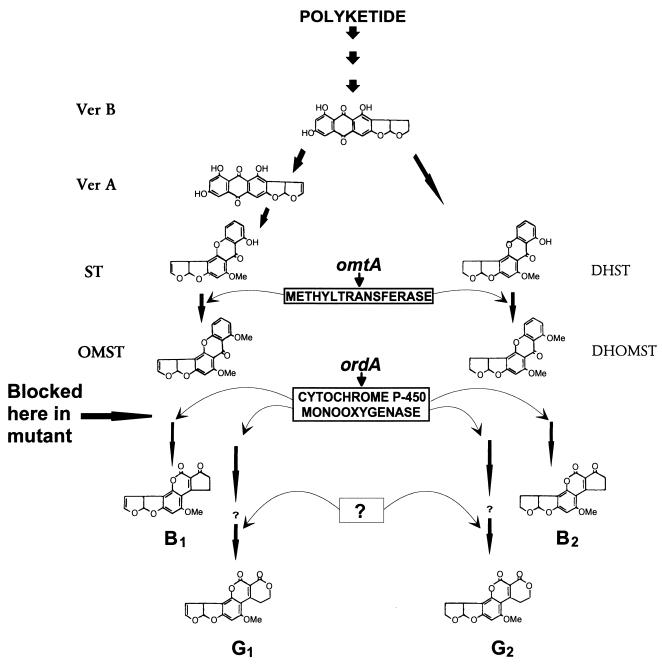

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the late steps in aflatoxin biosynthesis and postulated enzymatic steps involved in aflatoxin G1 and G2 production in A. parasiticus. The simplified scheme shows the formation of aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2, starting from polyketide and branching at Ver B. The precursors of aflatoxins B1 and G1 are Ver A, ST, and OMST, and the precursors of aflatoxins B2 and G2 are DHST and DHOMST. The ordA gene product, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase, is capable of converting OMST to aflatoxins B1 and G1 and DHOMST to aflatoxins B2 and G2. It has been proposed (indicated by question marks) that at least one additional enzyme is required for the production of aflatoxins G1 and G2 from postulated intermediates (5). Me, methyl group.

In this study, the ordA and ordA1 genes (homologs of ord1 of A. flavus) of the aflatoxigenic strain A. parasiticus SRRC 143 and of the OMST-accumulating strain A. parasiticus SRRC 2043, respectively, were cloned and characterized. Critical amino acid residues that affect the catalytic activity of the ordA gene product were identified by site-directed mutagenesis and by feeding studies in which fungal and yeast systems were used. The role of the ordA gene in the formation of aflatoxins G1 and G2 was also assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and culture conditions.

The following fungal strains were used: A. parasiticus SRRC 143 (= ATCC 56775), which produces aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2; A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 (= ATCC 62882), a field isolate which accumulates OMST and does not produce aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2; A. parasiticus RHN1, a spontaneous niaD (nitrate reductase gene) mutant derived from A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 (10), which was the recipient strain used in fungal transformation experiments; and A. flavus 86, which produces aflatoxins B1 and B2. Fungal strains were maintained on potato dextrose agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.); this medium and coconut agar medium (19) were also used for detection of aflatoxin production. For conidium production, cultures were grown on V8 agar plates (50 ml of V8 juice [a commercial beverage consisting of eight vegetable juices] per liter, 20 g of agar per liter; pH 5.2). A & M medium (1), which contained (per liter) 50 g of sucrose, 3 g of ammonium sulfate, 10 g of potassium phosphate, 2 g of magnesium sulfate, and 1 ml of a micronutrient mixture (pH 4.5), was used for growth of fungal mycelia as submerged cultures. Low-sugar replacement medium (1) (LSRM), which contained (per liter) 1.62 g of sucrose, 3 g of ammonium sulfate, 10 g of potassium phosphate, 2 g of magnesium sulfate, and 1 ml of a micronutrient mixture (pH 4.5), was used for precursor feeding studies.

Vector construction and fungal transformation.

A 5-kb ordA-containing XbaI-SalI fragment, which was constructed by removing a 4-kb SphI fragment from the 9-kb XbaI-SalI fragment in the pBC vector (Fig. 2) from A. parasiticus, was ligated to XbaI-SalI-digested pHD62 to give a transformation vector. The A. flavus ord1 gene in a 3.3-kb XbaI-HindIII fragment (38) was subcloned into the XbaI-HindIII sites of pHD62 and was used in transformation. Fungal protoplasts were transformed with a polyethylene glycol-CaCl2 protocol (27). Czapek solution agar (Difco Laboratories) supplemented with 0.6 M KCl and Cove’s micronutrients (17) was used as the protoplast regeneration medium.

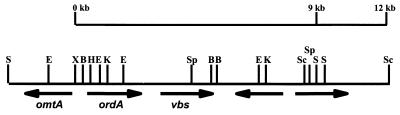

FIG. 2.

Restriction map of ordA and its neighboring genes in A. parasiticus SRRC 143. The arrows indicate the directions of gene transcription. The two newly identified open reading frames are indicated by unlabeled arrows. Abbreviations for restriction enzymes: B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI; Sc, SacII; S, SalI; Sp, SphI; X, XbaI.

In vivo fungal feeding studies.

Aflatoxin-producing ordA transformants in which restoration of the monooxygenase activity (i.e., conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1) may have occurred were also analyzed by performing precursor feeding studies. Three-day-old mycelia were harvested by filtration and were washed with LSRM. One gram of wet mycelia was transferred to a flask containing 20 ml of LSRM. Each precursor (60 μg of versicolorin B [Ver B] in 60 μl of acetone, 60 μg of versicolorin A [Ver A] in 60 μl of acetone, or 60 μg of DHST in 60 μl acetone) was added to two replicate flasks containing 10 ml of LSRM. The cultures were incubated at room temperature for 24 h with constant shaking at 150 rpm. The media and mycelia were extracted with acetone and chloroform as described previously (21). The metabolites extracted were assayed on a thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate (catalog no. 7001-04; 20 by 20 cm; silica gel; J. T. Baker, Inc.) by using an ether-methanol-water (96:3:1, vol/vol/vol) (EMW) solvent system.

Cloning of ordA and ord1 cDNA by reverse transcriptase PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from 48-h-old mycelia of SRRC 143 and SRRC 2043 by the hot phenol extraction method (2). First-strand cDNA was synthesized with an Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.) and was used as the template in PCR. PCR amplification was carried out as described previously (45). The resulting 1.7-kb full-length cDNA fragments were cloned into pCRII (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) and sequenced (39).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis was used to introduce point mutations into the ordA gene (24). This method consists of two rounds of PCR in which three pairs of oligonucleotide primers are used. Primer 1 contained a tagged HindIII site before the start codon ATG; primer 2 contained the designated change-of-coding sequence; the sequence of primer 3 was the reverse complementary sequence of primer 2; and primer 4 contained a tagged XbaI site downstream of the stop codon. The first-round PCR was performed with two pairs of primers (primers 1 and 2 amplified the region from the N terminus to the mutation site, and primers 3 and 4 amplified the region from the mutation site to the C terminus) and gave two slightly overlapping PCR products. The two PCR products were separated from the ordA template by agarose gel electrophoresis and were purified. The second-round PCR was performed with primers 1 and 4 and with the two PCR products as the templates and gave a full-length cDNA sequence containing the designated mutation and the restriction sites for cloning into yeast expression vector pYES2.

The following primers were used for the mutation His→Leu at position 400 (the restriction sites and the stop codon are underlined, and the altered bases are underlined and in boldface type): primer 1 (forward) (5′-GCACGATTCACTAAGCTTCCAGTACGATCGTCACTTGCC-3′), primer 2 (reverse) (5′-CTGGGATCAAGGGTAAACGTC-3′), primer 3 (forward) (5′-GACGTTTACCCTTGATCCCAG-3′), and primer 4 (reverse) (5′-CACCAGTCTAGATACCGAGCGGATATATATGTCCATC-3′). For the mutation Ala→Ser at position 143 the following two additional overlapping primers containing the desired changes were used: primer 5 (reverse, in place of primer 2) (5′-GGGATGAAAAGTCGAAATGGCTCGCCGTG-3′) and primer 6 (forward, in place of primer 3) (5′-CACGGCGAGCCATTTCGACTTTTCATCCC-3′). For the mutation Ile→Tyr at position 528 (amino acid 528 was the last amino acid before the stop codon) only one primer was used as a reverse primer in place of primer 4, which contained both the XbaI site and the designated change, as follows: primer 7 (reverse) (5′-GCGGATCTAGATGTCCATCAAGTCATCTGATTTCTGGCC-3′). One round of PCR with primers 1 and 7 was performed instead. All primers were made with a model 380A DNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems).

Construction of expression vectors and yeast transformation.

A. parasiticus ordA, ordA1 cDNA, and A. flavus ord1 cDNA, as well as ordA-derived cDNA with site-directed mutations, were subcloned into pYES2 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) and placed under the control of the inducible Saccharomyces cerevisiae GAL1 promoter. Transformation of S. cerevisiae INVSc1 with the resulting vectors was carried out by the polyethylene glycol-lithium acetate method (18). Positive transformants grew on yeast nitrogen base medium supplemented with tryptophan, histidine, and leucine (commercial mixture, 30 μg/ml) but without uracil (Clontech Laboratories).

Determination of monooxygenase activities encoded by ordA, ordA1, ord1, and ordA-derived cDNA in S. cerevisiae.

The yeast transformants grown on yeast nitrogen base medium supplemented with amino acids were induced with d-galactose (2%, wt/vol) for 24 h at 29°C with constant shaking at 150 rpm. Each yeast culture was diluted to a density of about 5 × 106 cells/ml; OMST (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added to the yeast culture to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml, and the culture was incubated for another 20 h. At the end of the incubation period, the yeast cultures were extracted with acetone and chloroform (21). The reaction products were spotted onto a TLC plate and developed with the EMW solvent system described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the ordA and ordA1 genes are AF017151 and AF054820, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification and characterization of the A. parasiticus ordA gene.

In a previous study, we identified the aflatoxin-biosynthetic gene cluster of A. parasiticus (46). To locate the gene encoding the putative oxidoreductase (3, 5, 11) that is involved in the conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 in A. parasiticus, we sequenced the entire 12-kb DNA region in previously identified cosmid clone 2 (see reference 46 for a detailed map). A BLAST search showed that an A. flavus ord1 gene homolog, ordA, was located between the omtA and vbs genes (Fig. 2). The ordA gene exhibited 92% identity to ord1; it was transcribed in a direction opposite the direction of omtA transcription but in the direction of vbs transcription (40).

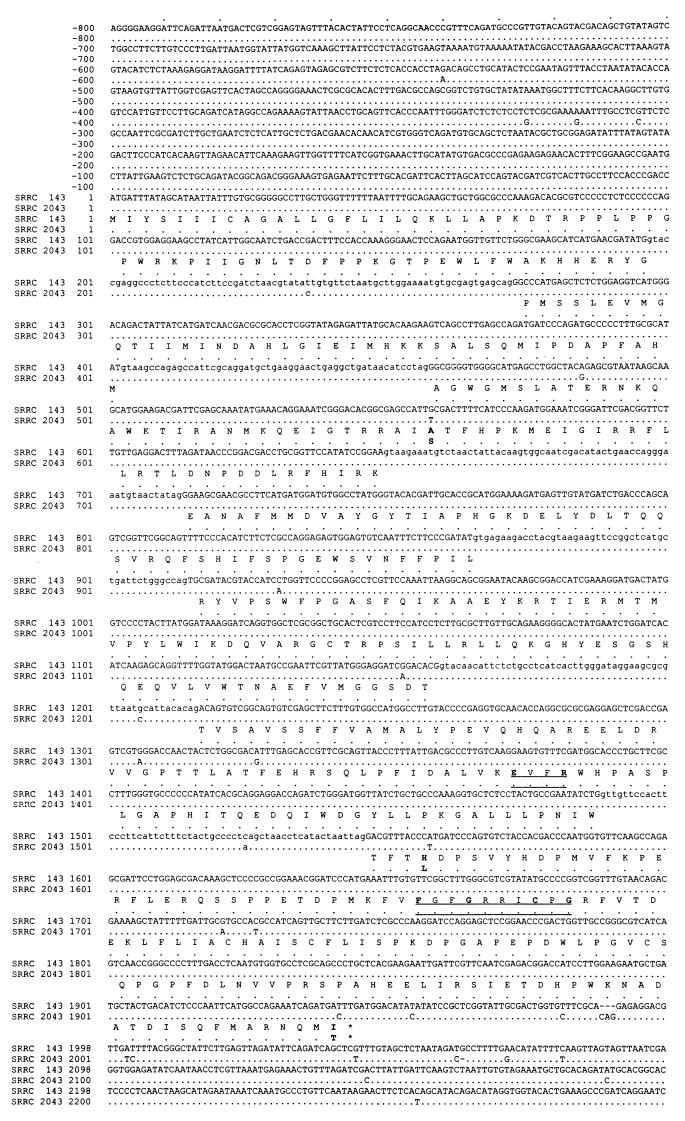

Figure 3 shows the DNA and predicted amino acid sequences of the ordA gene. The predicted ordA gene product exhibited 97% identity to the ord1 gene product of A. flavus. The ord1 gene product has been shown to be involved in the conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 (38). A comparison of the ordA genomic and cDNA sequences showed that the ordA gene contained six introns that ranged from 50 to 77 bp long and were typical of the consensus intron splicing GT⋯AG sequence. The gene structure of A. parasiticus ordA was identical to the gene structure of A. flavus ord1. Little homology was found between A. parasiticus ordA and the open reading frames identified in the Aspergillus nidulans ST-biosynthetic gene cluster, including the open reading frames that have been proposed to encode cytochrome P-450 type enzymes, such as stcB, stcF, stcL, and stcS (9, 29). The only significant homology with the open reading frames found in A. nidulans was homology with the conserved motifs reported for cytochrome P-450 type enzymes which are located near the carboxy terminus (namely, FXXGXXXCXG and EXXR) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Comparison of the genomic DNA sequences and deduced amino acid sequences of the ordA and ord1 genes of A. parasiticus SRRC 143 and SRRC 2043. The numbers on the left indicate the positions of the nucleotides, beginning from translation initiation codon ATG. The deduced amino acid sequence is numbered from the first amino acid, a methionine (M), and the translation termination (TAG) is indicated by an asterisk. For comparison, the nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of the ordA1 gene of SRRC 2043 are shown under the corresponding sequences; identical amino acid residues are represented by dots, and gaps are represented by dashes. The intron sequences are indicated by lowercase letters. The highly conserved regions of the amino acid sequences of the cytochrome P-450 enzymes are underlined, and the conserved amino acid residues are indicated by boldface type. The point mutations of three amino acid residues are also indicated by boldface type.

Molecular characterization of the OMST-accumulating strain A. parasiticus SRRC 2043.

A. parasiticus differs from A. flavus in that it not only produces aflatoxins B1 and B2 but also produces aflatoxins G1 and G2. The aflatoxin-producing ability of A. parasiticus is more stable than the aflatoxin-producing ability of A. flavus. To date, A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 is the only field strain isolated that does not produce aflatoxins but instead accumulates OMST (7). To investigate whether SRRC 2043 lacks the ordA1 gene, we performed a Southern blot analysis. Genomic DNA from SRRC 2043 and aflatoxigenic strain SRRC 143 were digested with SalI, XbaI, EcoRI, and HindIII and probed with a radiolabeled 1.2-kb EcoRI ordA-containing fragment (Fig. 2). The genomic DNA restriction patterns for the two A. parasiticus cultures were identical (results not shown), indicating that there was no apparent deletion large enough to be detected by Southern blot analysis in the ordA1 gene of SRRC 2043. The results also suggested that there was a single copy of the ordA1 gene in the A. parasiticus genome.

To find out whether the accumulation of OMST in SRRC 2043 is due to a lack of transcription of the ordA1 gene, we carried out a Northern blot analysis by using total RNA from the strains described above. A 2-kb transcript was detected with both SRRC 143 and SRRC 2043 (results not shown). This also indicated that there were no deletions in the ordA1 gene.

To further examine why SRRC 2043 is not able to convert OMST and DHOMST to aflatoxins, we cloned and sequenced the ordA1 gene of SRRC 2043 (Fig. 3). A comparison of ordA1 and ordA revealed that 3 of 12 nucleotide variations in the ordA1 gene coding sequence resulted in three amino acid substitutions. The deduced ordA1 gene product had Leu at position 400, Ser at position 143, and Thr at position 528, whereas the deduced amino acid sequence of the ordA gene product had His, Ala, and Ile at the corresponding positions, respectively. It was also determined that the gene product of ord1 (from A. flavus) had His at position 400 and Ile at position 528, like the gene product of the toxigenic organism A. parasiticus SRRC 143, but had Ser at position 143, like the gene product of A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Site-directed mutagenesis study of functional amino acid residues in cytochrome P-450 responsible for conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 and expression in a yeast system

| Source of cDNA | Amino acid residues in ordA gene product

|

Amt of aflatoxin B1 detected as estimate of conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position 143 | Position 400 | Position 528 | ||

| A. parasiticus SRRC 143 | A | H | I | ++ (control)b |

| A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 | S | L | T | − |

| A. flavus 86 | S | H | I | + |

| SRRC 143 His mutant | A | Lc | I | − |

| SRRC 143 His-Ala mutant | S | L | I | − |

| SRRC 143 Ala mutant | S | H | I | + |

| SRRC 143 Ala-Ile mutant | S | H | T | + |

| SRRC 143 Ile mutant | A | H | T | ++ |

| pYES2 vector | —d | — | — | − (control) |

Summary of results from three independent experiments.

One-fourth of the total extracted metabolites from each sample was used. ++, normal amount (approximately 10 μg) of aflatoxin B1 obtained from OMST in SRRC 143 with the yeast expression system; +, approximately one-half the normal amount of aflatoxin B1; −, no aflatoxin B1 detected.

Boldface type indicates modified amino acid residues.

—, no ordA gene was present.

Genetic complementation of SRRC 2043 with ordA of SRRC 143 and ord1 of A. flavus 86.

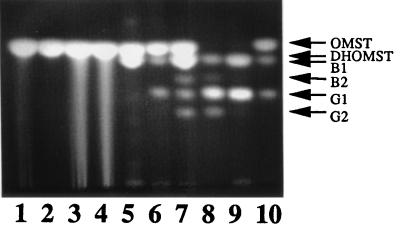

To determine if the amino acid substitutions in the gene products of ordA1 resulted in a loss of monooxygenase activity in SRRC 2043, we transformed A. parasiticus ordA and A. flavus ord1 into an SRRC 2043-derived recipient strain, RHN1, which was not able to produce aflatoxins (Fig. 4, lane 2). However, in repeated transformation experiments, more than 50% of the transformants generated from ordA and ord1 produced aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2 (Fig. 4, lanes 6, 7, and 10). This indicated that the substitutions in the ordA1 gene were the reason for the loss of the cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase activity that resulted in the accumulation of OMST and DHOMST in SRRC 2043.

FIG. 4.

TLC assay of toxin production by ordA-complemented transformants. One-fourth of the total extracted metabolites from each sample was loaded into a lane. The amount of aflatoxin B1 produced by SRRC 143 (lane 9) was approximately 10 μg. Lane 1, OMST standard; lane 2, SRRC 2043; lane 3, SRRC 2043 fed Ver B; lane 4, SRRC 2043 fed Ver A; lane 5, SRRC 2043 fed DHST; lane 6, SRRC 2043 complemented with the ordA gene from SRRC 143; lane 7, SRRC 2043 complemented with the ordA gene from SRRC 143 and fed DHST; lane 8, aflatoxin standard (aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2); lane 9, SRRC 143; lane 10, SRRC 2043 complemented with the ord1 gene from A. flavus and fed OMST (note that SRRC 2043 fed DHST produced a band immediately below the OMST band corresponding to DHOMST).

Aflatoxin precursor feeding of ordA and ord1 transformants.

Figure 4 shows that SRRC 2043 fed two earlier pathway precursors, Ver B and Ver A, produced increased levels of OMST (Fig. 4, lanes 3 and 4). It should be pointed out that usually a very small amount of DHOMST is produced by SRRC 2043 (results not shown). Therefore, analysis of the pathway branch leading to biosynthesis of aflatoxins B2 and G2 (3, 11) required feeding aflatoxin B2 and G2 precursors, such as DHST and/or DHOMST, in order to obtain definitive results. SRRC 2043 fed DHST produced a new intensely fluorescent metabolite just below OMST (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 7). This product was DHOMST (Fig. 4, lanes 5 and 7) since its migration pattern was consistent with previous TLC results (3, 11) obtained with the EMW solvent system that effectively separated DHST (Rf, 0.98), ST (Rf, 0.97), OMST (Rf, 0.44), DHOMST (Rf, 0.38), aflatoxin B1 (Rf, 0.37), aflatoxin B2 (Rf, 0.35), aflatoxin G1 (Rf, 0.28), and aflatoxin G2 (Rf, 0.25).

SRRC 2043 ordA transformants fed DHST produced significant amounts of aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2 in addition to increased amounts of DHOMST compared with amounts produced by SRRC 143 (Fig. 4, lane 7). SRRC 2043 ord1 transformants fed OMST produced aflatoxins B1 and G1 (Fig. 4, lane 10), but the quantities of the toxins were lower than the quantities produced by SRRC 2043 ordA transformants. These results showed that the ordA gene was involved in the formation of aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2 and that the ord1 gene product may not be as efficient as the ordA gene product.

Evaluation of amino acid substitutions in the gene products encoded by ordA, ordA1, and ord1 in the yeast expression system.

Complementation and feeding studies suggested that substitution(s) of certain amino acid residues was indeed responsible for inactivation of the monooxygenase activity. To assess the role of individual amino acids, we employed a yeast expression system in combination with site-directed mutagenesis and determined enzymatic activity in vivo.

Feeding studies performed with yeast cultures showed that A. parasiticus ordA and A. flavus ord1 converted exogenously supplied OMST to aflatoxin B1 (Fig. 5, lane 3), while ordA1 of the OMST-accumulating organism SRRC 2043 was not able to convert OMST to aflatoxin B1 (Fig. 5, lane 4). The yeast transformant containing only the pYES2 vector also could not convert OMST to aflatoxin (Fig. 5, lane 10). The lack of monooxygenase activity in the ordA1 gene product thus resulted from alteration of one or both of the following amino acid residues: Ala at position 143 and His at position 400.

FIG. 5.

Cytochrome P-450 enzyme activity assays of site-directed mutants expressed in yeast cells and TLC assays performed after A. parasiticus SRRC 143 and SRRC 2043 feeding studies. One-fourth of the total extracted metabolites from each sample was loaded into a lane. The amount of aflatoxin B1 converted from OMST by SRRC 143 (lane 3) was approximately 10 μg. Lane 1, aflatoxin standard (aflatoxins B1, G1, B2, and G2); lane 2, OMST standard; lane 3, SRRC 143 fed OMST; lane 4, SRRC 2043 fed OMST; lane 5, SRRC H400L 143 site mutant fed OMST; lane 6, SRRC 143 H400L and A143S double site mutant fed OMST; lane 7, SRRC 143 A143S site mutant fed OMST; lane 8, SRRC 143 A143S and I528T double site mutant fed OMST; lane 9, SRRC 143 I528T site mutant fed OMST; lane 10, yeast expression vector pYES2 with no ordA cDNA insert (negative control).

Table 1 summarizes the results of substitution of either single amino acid residue or two amino acid residues in the predicted polypeptide sequence of the ordA gene. When the His at position 400 was changed to Leu, as in SRRC 2043, the enzyme activity which converted OMST to aflatoxin B1 was completely lost (Fig. 5, lane 5). When the Ala at position 143 was changed to Ser, as in SRRC 2043, approximately 50% of the enzyme activity which converted OMST to aflatoxin B1 was lost (Fig. 5, lane 6). When the Ile at position 528 was changed to Thr, as in SRRC 2043, no change in the enzyme activity was observed (Fig. 5, lane 9). These results showed that the His at position 400 was critical for the enzyme activity and that the Ala at position 143 also played a significant role in the enzyme activity. However, substitution of Thr for Ile at position 528 did not affect the enzyme activity. The enzyme activities resulting from changes at two amino acid residues (His to Leu plus Ala to Ser and Ala to Ser plus Ile to Thr) were consistent with the activities resulting from single amino acid substitutions (either His to Leu or Ala to Ser) (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

It has been shown that cytochrome P-450 type enzymes are involved in the synthesis of various primary and secondary metabolites in filamentous fungi (42), including several mycotoxin-biosynthetic pathways. The genes for the cytochrome P-450 enzymes have been found in the aflatoxin (38, 45), ST (9), and trichothecene (25) biosynthesis pathway gene clusters. We have reported previously (45) that avnA, which is located in the A. parasiticus and A. flavus aflatoxin pathway gene clusters, exhibits homology to the genes that encode cytochrome P-450 monooxygenases. In A. nidulans, several of the transcripts involved in ST production have been shown to be homologous to genes that code for cytochrome P-450 type enzymes (9). In Fusarium sporotrichioides, a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase has been reported to be involved in tricothecene biosynthesis (25).

It has been proposed previously that conversion of OMST to aflatoxins involves an enzyme complex consisting of several catalytic activities (3, 5, 7), including dioxygenation and monooxygenation activities (5). It has also been predicted (12) and demonstrated (3) that this enzyme activity is membrane associated and requires NADPH as a cofactor. In this study, characterization of the function of the enzyme encoded by the ordA gene in a yeast expression system showed that this enzyme alone is sufficient to convert OMST to aflatoxin B1 and that no other aflatoxin pathway-specific enzyme is required to complement this reaction. These results are similar to those reported for the ord1 gene of A. flavus (38). The ordA1 gene product of the OMST-accumulating isolate A. parasiticus SRRC 2043 was, however, not able to carry out a similar reaction. Since the enzyme activity for conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 was observed in a yeast expression system in vivo, this system must have contained all of the necessary components (such as NADPH) of successful enzyme activity assays. Details of the postulated mechanisms for conversion of OMST to aflatoxins B1 and G1 and for conversion of DHOMST to aflatoxins B2 and G2 have been discussed previously (5, 32).

The ordA gene product is apparently a cytochrome P-450 type enzyme because NADPH is required as a cofactor for activity, and the ordA gene product contains two highly conserved regions characteristic of cytochrome P-450s (Fig. 3). The two regions are the heme-binding motif with the conserved amino acid residues FXXGXXXCXG (amino acids 433 to 442) and the hydrogen bond region defined by the amino acids EXXR (amino acids 358 to 361). These regions are considered the active sites of the cytochrome P-450 type enzymes (8, 31, 35, 37, 38, 45). The cysteine residue in the FXXGXXXCXG motif provides a ligand (the fifth ligand for the heme iron) for heme binding (35, 38, 45), and the amino acid residues adjacent to the cysteine form a unique environment that defines the heme binding pocket. The EXXR sequence is believed to hydrogen bond with the “meander” sequence located approximately 14 amino acids from the amino terminus of the heme-binding loop. In addition to these motifs, the highly hydrophobic region of about 20 amino-terminal residues (amino acids 1 to 19) of the ordA gene product may serve as a membrane-spanning anchor, a characteristic common to all microsomal cytochrome P-450 enzymes (20, 22, 33). The enzyme required for conversion of OMST to aflatoxin B1 was determined to be associated with the microsomal fraction (3, 12, 16). The ordA gene has been designated CYP64 by The Cytochrome P450 Nomenclature Committee (34).

The yeast expression system has proven to be an extremely valuable experimental tool for studying a specific enzyme activity because the nonhost gene can be transformed into the yeast system and the activity can be measured without interference since none of the aflatoxin pathway genes are present in the yeast genetic background (38). Site-directed mutagenesis is a very powerful tool for identifying the amino acid residues critical for the catalytic activity of an enzyme. By using this tool and transforming mutated genes into the yeast expression system, we were able to determine that the amino acid residues His-400 and Ala-143 are necessary for enzyme activity.

The His-400 residue is located between the EXXR and heme-binding motifs. Ala-143 is located far from the conserved cytochrome P-450 motifs, especially the heme-binding motif involved in the fundamental monooxygenase activity. These critical His-400 and Ala-143 residues are, therefore, not involved in either heme binding or hydrogen bonding but may be involved in substrate binding. Therefore, any modifications in these residues should render the enzyme inactive. In the CYP2 family of cytochrome P-450 enzymes, the substrate recognition sites seem to be spread around the primary amino acid sequences of the protein (23).

It is known that A. flavus strains are not able to produce group G aflatoxins (aflatoxins G1 and G2), whereas A. parasiticus can produce these toxins in addition to the group B aflatoxins (aflatoxins B1 and B2) (Fig. 1). Since feeding studies of the fungal system performed with ordA of A. parasiticus resulted in the formation of all four aflatoxins (Fig. 4), we postulated that the differences at amino acid position 143 between the A. flavus ord1 gene product (S143) and the A. parasiticus ordA gene product (A143) may in some way explain the lack of conversion of OMST and DHOMST to aflatoxins G1 and G2 in A. flavus. However, when ord1 was transformed into A. parasiticus, aflatoxins G1 and G2 were produced. This suggests that the substitution of serine (in A. flavus) for alanine (in A. parasiticus) is not the reason why A. flavus does not produce aflatoxins G1 and G2; an additional gene product(s) or catalytic activity may be needed to produce aflatoxins G1 and G2 in A. parasiticus (Fig. 1), which are not present in A. flavus. This was confirmed by our observations obtained with the yeast expression system, in which OMST feeding (Fig. 5, lane 3) of the yeast, which contained a vector harboring the ordA gene of A. parasiticus, resulted in aflatoxin B1 production and no aflatoxin G1 production. This suggests that at least one additional reaction may be needed for the production of the group G toxins in A. parasiticus.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Charles P. Woloshuk, Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Ind., for providing the yeast expression vector, as well as the 3.3-kb ord1 genomic DNA clone, Alan Lax for helpful discussions, Herb Holen and Becky Prima for technical assistance, and Linda Deer for secretarial help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adye J, Mateles R I. Incorporation of labeled compounds into aflatoxins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;86:418–420. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(64)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K. Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1987. pp. 4.3.1–4.3.4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Kingston D G I. Enzymological evidence for separate pathways for aflatoxin B1 and B2 biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 1991;30:4343–4350. doi: 10.1021/bi00231a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatnagar D, Cotty P J, Cleveland T E. Preharvest aflatoxin contamination: molecular strategies for its control. In: Spanier A M, Okai H, Tamura M, editors. Food flavor & safety: molecular analysis and design. Washington, D.C: American Chemical Society; 1993. pp. 272–292. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatnagar D, Ehrlich K C, Cleveland T E. Oxidation-reduction reactions in biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. In: Bhatnagar D, Lillehoj E B, Arora D K, editors. Handbook of applied mycology. 5. Mycotoxins in ecological systems. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1992. pp. 255–286. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatnagar D, Ullah A H J, Cleveland T E. Purification and characterization of a methyltransferase from Aspergillus parasiticus SRRC 163 involved in aflatoxin biosynthetic pathway. Prep Biochem. 1988;18:321–349. doi: 10.1080/00327488808062532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatnagar D, McCormick S P, Lee L S, Hill R A. Identification of O-methylsterigmatocystin as an aflatoxin B1 and G1 precursor in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1028–1033. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.5.1028-1033.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bozak K R, Yu H, Sirevag R, Christoffersen R E. Sequence analysis of ripening-related cytochrome P-450 cDNAs from avocado fruit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3904–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown D W, Yu J-H, Kelkar H S, Fernandes M, Nesbitt T C, Keller N P, Adams T H, Leonard T J. Twenty-five coregulated transcripts define a sterigmatocystin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1418–1422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang P-K, Cary J, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Bennett J W, Linz J E, Woloshuk C P, Payne G A. Cloning of the Aspergillus parasiticus apa-2 gene associated with the regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3273–3279. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.10.3273-3279.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleveland T E. Conversion of dihydro-O-methylsterigmatocystin to aflatoxin B2 by Aspergillus parasiticus. Arch Environ Contam Toxicol. 1989;18:429–433. doi: 10.1007/BF01062369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cleveland T E, Bhatnagar D. Individual reaction requirements of two enzyme activities, isolated from Aspergillus parasiticus, which together catalyze conversion of sterigmatocystin to aflatoxin B1. Can J Microbiol. 1987;33:1108–1112. doi: 10.1139/m87-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cleveland T E, Bhatnagar D. Evidence for de novo synthesis of an aflatoxin pathway methyltransferase near the cessation of active growth and the onset of aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus mycelia. Can J Microbiol. 1990;36:1–5. doi: 10.1139/m90-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleveland T E, Bhatnagar D. Molecular strategies for reducing aflatoxin levels in crops before harvest. In: Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, editors. Molecular approaches to improving food quality and safety. New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1992. pp. 205–228. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cleveland T E, Cary J W, Brown R L, Bhatnagar D, Yu J, Chang P-K, Chlan C A, Rajasekaran K. Use of biotechnology to eliminate aflatoxin in preharvest crops. Bull Inst Compr Agric Sci Kinki Univ. 1997;5:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleveland T E, Lax A R, Lee L S, Bhatnagar D. Appearance of enzyme activities catalyzing conversion of sterigmatocystin to aflatoxin B1 in late-growth-phase Aspergillus parasiticus cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1711–1713. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.7.1711-1713.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cove D J. The induction and repression of nitrate reductase in the fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;113:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6593(66)80120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniel R D, Woods R A. High efficiency transformation with lithium acetate. In: Johnson J R, editor. Molecular genetics of yeast: a practical approach. New York, N.Y: Oxford University Press; 1994. pp. 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis N D, Iyer S K, Diener U L. Improved method of screening for aflatoxin with a coconut agar medium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1593–1595. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.7.1593-1595.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donaldson R P, Luster D G. Multiple forms of plant cytochromes P-450. Plant Physiol. 1991;96:669–674. doi: 10.1104/pp.96.3.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dutton M F. Enzymes and aflatoxin biosynthesis. Microbiol Rev. 1988;52:274–295. doi: 10.1128/mr.52.2.274-295.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez F J. The molecular biology of cytochrome P450. Pharmacol Rev. 1989;40:243–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotoh O. Substrate recognition sites in cytochrome P450 family 2 (CYP2) proteins inferred from comparative analyses of amino acid and coding nucleotide sequences. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:83–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho S N, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:61–68. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hohn T M, Desjardins A E, McCormick S P. The Tri4 gene of Fusarium sporotrichioides encodes a cytochrome P450 monooxygenase involved in trichothecene biosynthesis. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:95–102. doi: 10.1007/BF02456618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hopwood D A, Sherman D H. Molecular genetics of polyketides and its comparison to fatty acid biosynthesis. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:37–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.000345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horng J S, Chang P-K, Pestka J J, Linz J E. Development of a homologous transformation system for Aspergillus parasiticus with the gene encoding nitrate reductase. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:294–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00271564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jelinek C F, Pohland A E, Wood G E. Worldwide occurrence of mycotoxins in foods and feeds—an update. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1989;72:223–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller N P, Brown D, Butchko R A E, Fernandes M, Kelkar H, Nesbitt C, Segner S, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Adams T H. A conserved polyketide mycotoxin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. In: Eklund M, Richard J L, Mise K, editors. Molecular approaches to food safety issues involving toxic microorganisms. Ft. Collins, Colo: Alaken Inc.; 1995. pp. 263–277. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahanti N, Bhatnagar D, Cary J W, Joubran J, Linz J E. Structure and function of fas-1A, a gene encoding a putative fatty acid synthetase directly involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:191–195. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.191-195.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maloney A P, VanEtten H D. A gene from the fungal plant pathogen Nectria haematococca that encodes the phytoalexin-detoxifying enzyme pisatin demethylase defines a new cytochrome P450 family. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:506–514. doi: 10.1007/BF00284198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Minto R E, Townsend C A. Enzymology and molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Chem Rev. 1997;97:2537–2555. doi: 10.1021/cr960032y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nebert D W, Gonzalez F J. P450 genes: structure, evolution, and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:945–993. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.004501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson, D. R. Personal communication.

- 35.Nhamburo P T, Gonzalez F J, McBride O W, Gelboin H V, Kimura S. Identification of a new P450 expressed in human lung: complete cDNA sequence, cDNA-directed expression, and chromosome mapping. Biochemistry. 1989;28:8060–8066. doi: 10.1021/bi00446a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne G A, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Linz J E. Genetic organization and regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus flavus and A. parasiticus. In: Eklund M, Richard J L, Mise K, editors. Molecular approaches to food safety issues involving toxic microorganisms. Ft. Collins, Colo: Alaken Inc.; 1995. pp. 249–261. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Potenza C L, Pendurthi U R, Strom D K, Tukey R H, Griffin K J, Schwab G E, Johnson E F. Regulation of the rabbit cytochrome P-450 3c gene. Age-dependent expression and transcriptional activation by rifampicin. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16222–16228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prieto R, Woloshuk C P. ord1, an oxidoreductase gene responsible for conversion of O-methylsterigmatocystin to aflatoxin in Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1661–1666. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1661-1666.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Silva J C, Minto R E, Barry III C E, Holland K A, Townsend C A. Isolation and characterization of the versicolorin B synthase gene from Aspergillus parasiticus. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13600–13608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trail F, Mahanti N, Rarick M, Mehigh R, Liang S-H, Zhou R, Linz J E. A physical and transcriptional map of an aflatoxin gene cluster in Aspergillus parasiticus and the functional disruption of a gene involved early in the aflatoxin pathway. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2665–2673. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2665-2673.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van den Brink J M, Van Gorcom R F M, Van den Hondel C A M J J, Punt P J. Cytochrome P450 enzyme systems in fungi. Fungal Genet Biol. 1998;23:1–17. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yabe K, Ando Y, Hamasaki T. Biosynthetic relationship among aflatoxins B1, B2, G1, and G2. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:2101–2106. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.8.2101-2106.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu J, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Keller N P, Chu F S. Cloning and characterization of a cDNA from Aspergillus parasiticus encoding an O-methyltransferase involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3564–3571. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.11.3564-3571.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu J, Chang P-K, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E. avnA, a gene encoding a cytochrome P-450 monooxygenase, is involved in the conversion of averantin to averufin in aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1349–1356. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1349-1356.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yu J, Chang P-K, Cary J W, Wright M, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E, Payne G A, Linz J E. Comparative mapping of aflatoxin pathway gene clusters in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2365–2371. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2365-2371.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu J, Chang P-K, Payne G A, Cary J W, Bhatnagar D, Cleveland T E. Comparison of the omtA genes encoding O-methyltransferases involved in aflatoxin biosynthesis from Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus. Gene. 1995;163:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00397-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]