Abstract

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the long-term antibody kinetics after vaccinating with an inactivated COVID-19 Vero cell vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthcare workers (HCWs) at a single center in Turkey.

Methods

For this prospective observational study, Chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) were used for the determination of binding antibodies (bAb) and neutralizing antibodies (nAb), respectively. Antibody kinetics were compared for the potential influencing factors, and propensity score analysis was performed to match the subcohort for age.

Results

Early bAb and nAb response was achieved in all 343 participants. Titers of bAbs against SARS-CoV-2 on 42 days post-vaccination (dpv) were higher in HCWs who were aged <40 years and who had a history of COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 bAb levels in HCWs on days 42 (n = 97), 90 (n = 97), and 180 (n = 97) were 175 IU/ml (3.9-250), 107 IU/ml (2.4-250), and 66.1 IU/ml (2.57-250), respectively (p<0.001). SARS-CoV-2 bAb (p<0.001) and nAb (p<0.001) titers decreased significantly over time. There was a high negative correlation between SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers and inverse optic density of nAb responses (Pearson correlation coefficient: -0.738, p<0.001).

Conclusions

When the antibody responses were compared, it was seen that the vaccine immunogenicity was better in those who had prior COVID-19 history and were aged <40 years. In the course of time, it was determined that there was a significant decrease in bAb and nAb responses after the 90th day. These results may guide approval decisions for booster COVID-19 vaccines.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected millions of people worldwide and caused more than five million deaths (WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard, 2022). Healthcare workers (HCWs) are among the most affected risk groups by the pandemic (Ran et al., 2020; Sim, 2020). Vaccines play a key role in the control of infection during the pandemic process that the whole world has been in for almost two years (Damasceno et al., 2021). Although many countries worldwide had the opportunity to access messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) vaccines, inactivated vaccines were the only available option in some countries. Rapidly published mRNA vaccine results were useless in countries, such as Turkey, that were implementing inactivated vaccines, which started vaccination firstly with HCWs and older adults against COVID-19 with CoronaVac (Daily Sabah, 2021).

SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that belongs to the family Coronaviridae. It has four major structural proteins; envelope (E), membrane (M), nucleocapsid (N), and spike (S) protein. Among them, the S and N proteins are the principal immunogens inducing anti-SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies (Henss et al., 2021; Walls et al., 2020). Antibodies that bind to the S protein neutralize coronaviruses (Henss et al., 2021). Neutralizing activity may be detectable nearly up to 14 months after primary infection (Rosati et al., 2021). The S protein is the antigenic target for the development of most vaccines (Sadarangani et al., 2021). Vaccines stimulate the production of antibodies that inhibit the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells. By this mechanism, the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 receptor-binding domain (ACE2-RBD) binding interactions and/or S antigen mediated membrane fusion are blocked. Functional neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) are important for viral clearance and protection from re-infection. Vaccine-induced antibody responses, neutralizing activities, and duration of these responses are different according to the type of vaccines (Lim et al., 2021). In addition, it is difficult to compare the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in phase III clinical trials and further studies because of the lack of standardization in geometric mean titer (GMT) of nAb values, the usage of different immunoassays by different developers, and the difference in dosage and administration schedules (Karim, 2021; Rogliani et al., 2021).

CoronaVac, developed by Sinovac/China National Pharmaceutical Group in Beijing/China, is a whole-virus inactivated COVID-19 vaccine. The vaccine showed acceptable safety and immunogenicity in healthy adults aged 18-59 years and 60 years and above in phase I/II and phase III clinical trials (Fadlyana et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021). Turkey started vaccination with CoronaVac on January 13, 2021, with HCWs (https://covid19asi.saglik.gov.tr/TR77706/covid-19-asisi-ulusal-uygulama-stratejisi.html, COVID-19 Vaccine National Implementation Strategy, 2021). Although inactivated vaccine technologies are familiar and have a long history, the CoronaVac vaccine has recently been developed for the pandemic. In the limited amount of research conducted on CoronaVac vaccination in healthy adults (Banga Ndzouboukou et al., 2021; Bayram et al., 2021; Bichara et al., 2021; Bueno et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Hunsawong et al., 2021), a maximum of 56 days of short-term follow-up was evaluated, and better immunogenicity was mostly demonstrated in the participants who had a COVID-19 history before vaccination.

This study aimed to quantitatively analyze antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S protein and determine the neutralizing activity of the antibodies in the 6-month period following CoronaVac vaccination in HCWs to reveal the antibody kinetics.

Materials and methods

Study design, ethical statement, and permissions

This prospective observational study was conducted on HCWs at the Gazi University Hospital between February 2021 and August 2021. The study protocols were approved by the COVID-19 scientific research commission of the Turkish Ministry of Health and Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Gazi University with decision number 182 on 22 February 2021. All participants provided informed consent.

Study population, groups, and definitions

The inclusion criteria for the study were age over 18 years and receiving two vaccinations of CoronaVac 28 days apart. The exclusion criteria were confirmed SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positivity after the first dose of the CoronaVac vaccine and having any condition that has a known effect on vaccine response, such as pregnancy and immunosuppressive condition or drug usage.

Previous COVID-19 history is defined as the diagnosis of COVID-19 confirmed with SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity before the first dose of the CoronaVac vaccine. Those who had a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result in the follow-up after the first dose of the vaccine were excluded. The results of the SARS-CoV-2 PCR tests, taken from HCWs who had symptoms or were in contact with the symptomatic case, were obtained from the hospital surveillance system.

The antibody titer change (Δ) is calculated as the difference between the GMT values of the binding antibody (bAb) titers detected by ELISA between days 42-90 and 42-180.

Data and sera collection

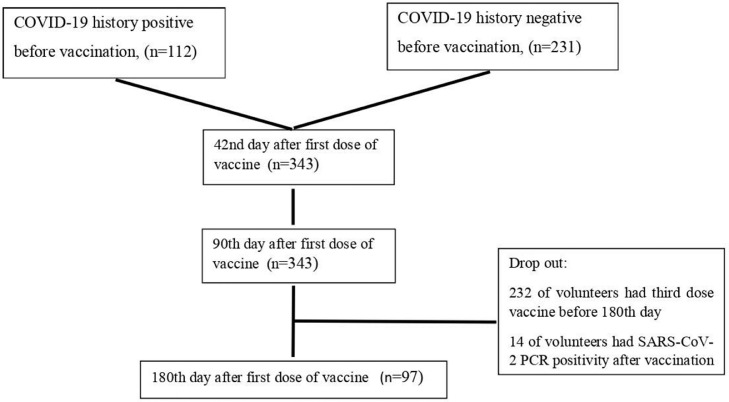

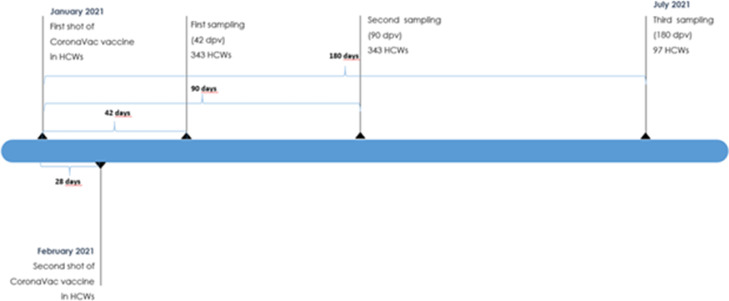

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the antibody kinetics on the 42nd, 90th, and 180th day after the first dose of CoronaVac without interfering with the vaccination decision of the volunteers. Sera (3-4 ml of a venous blood sample) were obtained on the 42nd, 90th, and 180th days after the first vaccination dose, respectively. All specimens were coded before processing. A flowchart of the study is shown in Fig 1 , and a timeline of the vaccination and sampling of HCWs is shown in Fig 2 .

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

Figure 2.

Timeline of the vaccination and sampling of HCWs.

The demographic information and medical history of the volunteers (comorbidity, drug usage, allergy history, SARS-CoV-2 PCR positivity date, first and second dose vaccination dates) were recorded using a questionnaire at the time of taking initial serum samples. The blood samples taken were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes in the Gazi University Hospital Infectious Diseases laboratory, and the separated sera were taken into 2 ml Eppendorf tubes and stored at -86 degrees Celcius. On the study day, serum samples were removed from the freezer and transferred to Gazi University Department of Immunology Laboratory, accordingly to the relevant guidelines (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020; https://shgmtetkikdb.saglik.gov.tr/Eklenti/37137/0/covid-19-sars-cov-2-enfeksiyonu-laboratuvar-biyoguvenlik-rehberipdf.pdf; COVID-19 [SARS-CoV-2 Infection] Laboratory Biosafety Guide, 2020).

Measurement and analysis of binding antibody (bAb) titers against SARS-CoV-2 S protein in sera

All serum samples were analyzed with a chemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche, Elecsys® Anti-SARS-CoV-2 S Quant) developed for the quantitative determination of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 S protein on the Cobas 8000 e801 system available in the Gazi University Diagnostic Immunology Laboratory. According to the manufacturer's instructions, a titer of ≥ 0.8 U/mL is considered reactive, and a titer of < 0.8 U/mL is considered non-reactive.

Measurement and analysis of neutralizing antibody (nAb) titers of ACE2-RBD (receptor-binding domain) in sera

All serum samples were analyzed with ELISA to determine the inhibitory activity of RBD-ACE2 binding induced by nAbs to SARS-CoV-2 in human sera. For this process, the ACE2-RBD Neutralization Assay - ELISA kit developed by Dia Pro (Diagnostic Bioprobes Srl, Milano, Italy) was used. The procedure was carried out in the Gazi University Department of Immunology Laboratory. Microplates are coated with SARS-CoV-2 specific recombinant glycosylated RBD. Serum samples of the volunteers and negative and positive controls of the previously mentioned ELISA kit are added to the wells and incubated according to the manufacturer's instructions. Recombinant ACE2 biotinylated antigen and Streptavidin-HRP are added after washing. Finally, the color intensity of the solution in each well is measured with an ELISA microplate reader (Biotek Synergy HT). The presence and higher level of neutralizing antibodies are reflected by lower signal formation. Calculations were made according to the formula as stated in the user manual of the test. Accordingly, the average of the negative controls (NC) was divided into 2, and the cut-off value (mean NC/2 = cut-off [Co]) was calculated. This value was used to interpret the results. For interpretation, the ratio of the Co and sample optic density (OD) 450 nm/620-630 nm (S) were found. If the Co/S value is less than and equal to 1, it is considered as negative, and if it is greater than 1, it is considered as a positive result.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac version 25.0 for Mac OS X (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). The normality of the data distribution was determined by the Shapiro-Wilk test, histogram, and Q-Q plots. The categorical values of the patients were expressed as a number and a percentage and were analyzed with a chi-square test. Continued values were presented as mean and standard deviation or median values and an interquartile range of 25-75%. The nonparametric values were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test and the parametric values with Student's t-test. The one-way analysis of variance test was used to compare the geometric mean of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies by risk factors. Comparison of nonparametric and parametric dependent variables was done with the Friedman test and Cochrane Q test. Vaccine responses were compared in the cohort for potential factors that could influence the antibody response and in the subcohort matched for age with propensity matching. The 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated whenever appropriate, and a two-tailed P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Graphs were created using the GraphPad version 9 program.

Results

A total of 343 HCWs were enrolled in the study. The median age of the participants was 38 years (29-47), and 63.6% (n = 218) of them were female. A total of 37.5% of HCWs (n = 112) had a COVID-19 history before vaccination. Of these 112 HCWs, 35.3% (n = 40) had COVID-19 in the last 3 months, 39.2% (n = 44) in between 3-6 months, and 25% (n = 28) more than 6 months before vaccination.

On day 42, the GMT of binding antibodies against the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 after two doses of CoronaVac vaccine was 168 (3.9-250).

The SARS-CoV-2 antibody response of the HCWs 42 days post-vaccination (dpv) was evaluated according to age, sex, and COVID-19 history (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

SARS-CoV-2 antibody response of the healthcare workers (HCWs) on 42 days post-vaccination (dpv)

| Binding antibody level (GMT) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <40 (min-max) (n = 190) | 205 (23-250) | <0.001a |

| ≥40 (min-max) (n = 153) | 131 (3.9-250) | |

| Sex | ||

| Female (min-max) (n = 218) | 169 (3.9-250) | 0.871a |

| Male (min-max) (n = 125) | 166 (4.78-250) | |

| COVID-19 history | ||

| Yes (n = 112) | 206 (14.1-250) | <0.001a |

| No (n = 231) | 150 (3.9-250) | |

| aOne-way ANOVA | ||

GMT: geometric mean titers.

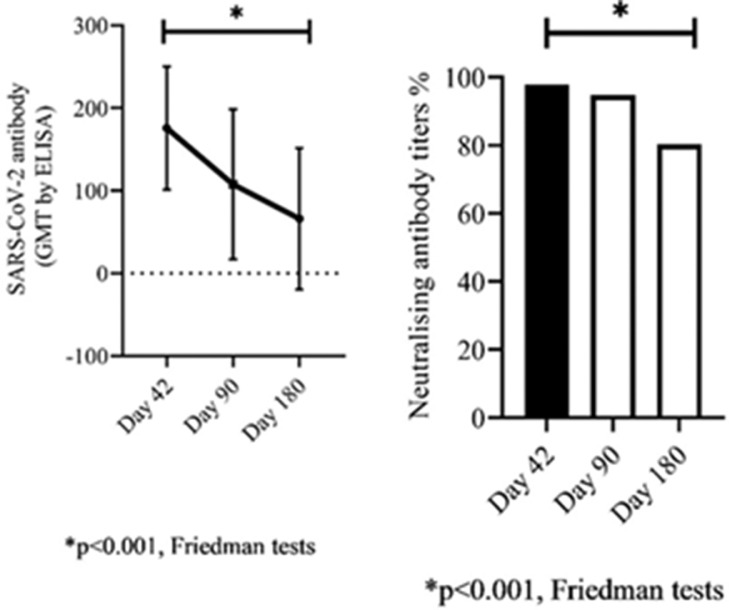

Binding antibody GMTs against SARS-CoV-2 were assessed at 42 dpv, 90 dpv in all HCWs, and at 180 dpv in 97 of them. Binding antibody GMTs in HCWs on days 42, 90, and 180 were 168.0 ± 78.4, 99 ± 90.3, and 66.1 ± 85.5, respectively (Friedman test, p<0.001).

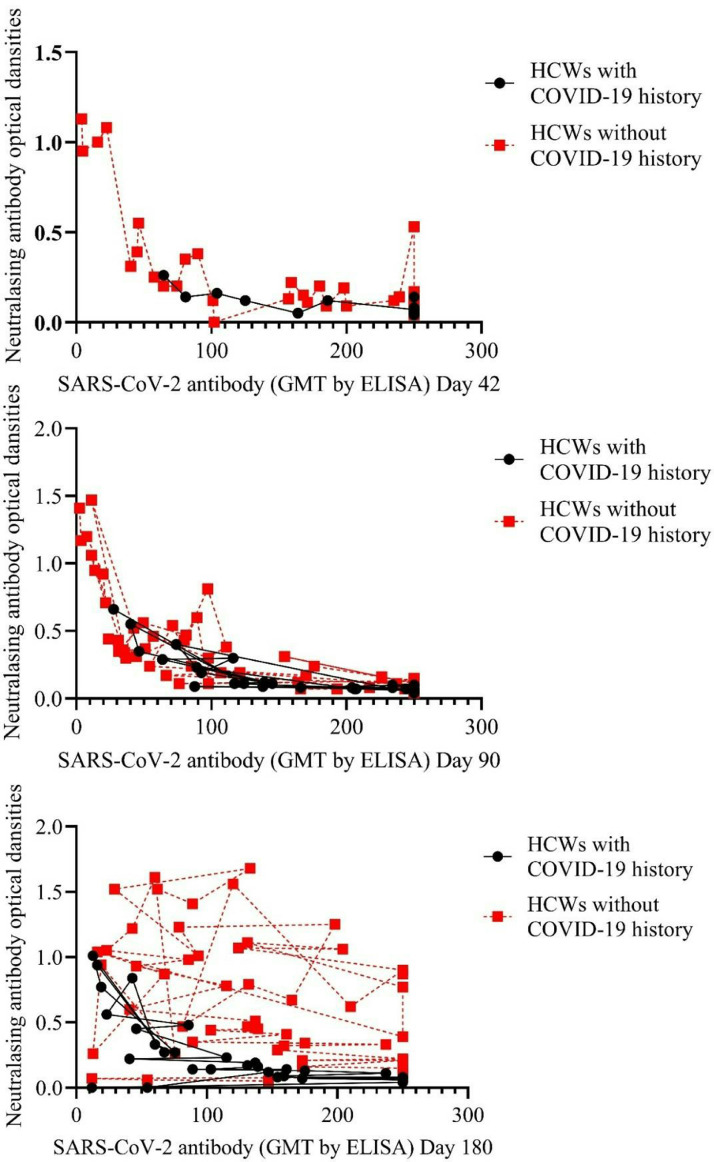

Comparison of GMTs of SARS-CoV-2 bAbs and percentage of ACE2-RBD nAbs responses in 97 HCWs for age and history of COVID-19 on 42, 90, and 180 dpv is listed in Table 2 and shown in Fig 3 .

Table 2.

Comparison of antibody responses in 97 healthcare workers (HCWs) for age and history of COVID-19 on 42, 90, and 180 days post-vaccination (dpv)

| Study Cohort, N = 97 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 42 dpv | 90 dpv | 180 dpv | p-value | |

| GMTs of binding antibodies, (Min-Max) | 175 (3.9-250) | 107 (2.4-250) | 66.1 (2.57-250) | <0.001a |

| HCWs with COVID-19 history (n = 58) | 221 (64-250) | 163 (27-250) | 107 (11-250) | <0.001a |

| HCWs without COVID-19 history (n = 39) | 150 (3.9-250) | 81 (2.4-250) | 47 (2.5-250) | <0.001a |

| HCWs ≤40 age (n = 67) | 216 (40-250) | 138 (11-250) | 84 (9.5-250) | <0.001a |

| HCWs >40 age (n = 30) | 110 (3.9-250) | 61 (2.4-250) | 38 (2.5-250) | <0.001a |

| ODs of nAbs, n (%) | 95 (97.9) | 92 (94.8) | 78 (80.4) | <0.001b |

| HCWs with COVID-19 history (n = 58) | 39 (100) | 39 (100) | 35 (89.7) | 0.018b |

| HCWs without COVID-19 history (n = 39) | 56 (96.6) | 53 (91.4) | 43 (74.1) | <0.001b |

| HCWs ≤40 age (n = 67) | 67 (100) | 66 (98.5) | 57 (85.1) | <0.001b |

| HCWs >40 age (n = 30) | 28 (93.3) | 26 (86.7) | 21 (70.0) | 0.008b |

Friedman tests

Cochrane Q tests

GMT = geometric mean titer; HCW = healthcare worker; nAb = neutralising antibody; OD = optic density.

Figure 3.

The change of geometric mean titers (GMTs) of binding antibodies (bAbs) and percentage of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) in 97 healthcare workers (HCWs) on 42, 90, and 180 days post-vaccination (dpv).

Vaccine responses for age and COVID-19 history were compared in the study cohort and the age-matched subcohort and listed in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Comparison of vaccine responses for age and COVID-19 history in the study cohort and the age-matched subcohort

| Study cohort, N = 97 |

Propensity matching subcohort, N = 36 |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCWs ≤ 40 age, N = 67 | HCWs > 40 age, N = 30 | p-value | HCWs with COVID-19 history, N = 39 | HCWs without COVID-19 history, N = 58 | p-value | HCWs with COVID-19 history, N = 18 | HCWs without COVID-19 history, N = 18 | p-value | |

| Age, (IQR 25%-75%) | - | - | - | 28 (26-39) | 37 (30-47) | 0.001 | 32.5 (26-39) | 33 (27.5-38.7) | 0.988 |

| Sex, n (%), male | 30 (44.8) | 8 (26.7) | 0.091 | 18 (46.2) | 20 (34.5) | 0.248 | 8 (44.4) | 7 (38.9) | 0.735 |

| bAb titers on 42 dpv, GMT (min-max) | 216 (40-250) | 110 (3.9-250) | <0.001a | 221 (64-250) | 150 (3.9-250) | 0.013a | 174 (2.5-250) | 215 (40-250) | 0.596a |

| nAb on 42 dpv, n (%) | 67 (100) | 28 (93.3) | 0.029 | 39 (100) | 56 (96.6) | 0.149 | 18 (100) | 17 (94.4) | 0.234 |

| Change in bAb titer from 42 to 90 dpv, GMT (min-max) | 34.8 (0-118) | 30.1 (0-72) | 0.612 | 6 (0-84) | 52 (0.9-128) | 0.039 | 0 (0-101) | 67.4 (0-145) | 0.239 |

| Change in bAb titer from 42 to 180 dpv, GMT (min-max) | 126 (35-168) | 50 (8.6-117) | 0.048 | 89 (0-135) | 129 (39-173) | 0.054 | 83 (0-131) | 139 (94-178) | 0.022 |

One way ANOVA

IQR = interquartile range; GMT = geometric mean titer; bAb = binding antibody; nAb = neutralising antibody; dpv = days-post-vaccination.

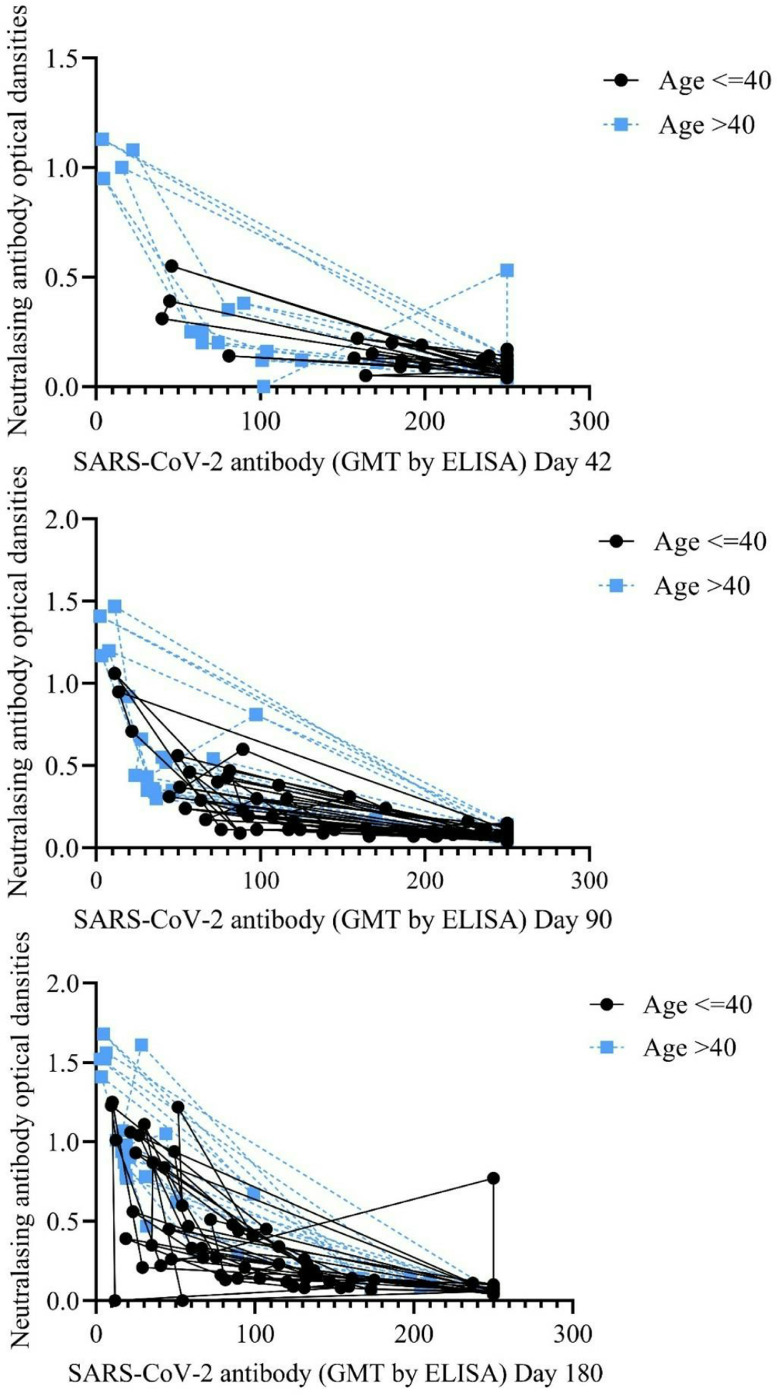

There was a negative high correlation between bAb titers against SARS-CoV-2 and ODs of nAb responses (Pearson correlation coefficient: -0.738, p<0.001). The correlation between bAb titers against SARS-CoV-2 and ODs of nAb responses was evaluated according to COVID-19 history and age (Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Figure 4.

Correlation between binding antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 and neutralizing antibody responses according to age .

Figure 5.

Correlation between binding antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 and neutralizing antibody responses according to COVID-19 history .

Discussion

In the study, a high titer of binding and neutralizing antibody response was detected on 42 dpv in most HCWs. This antibody response was significantly higher, especially in HCWs under the age of 40 years. Furthermore, 90 days after the first vaccine dose, binding antibody titers and percentages of neutralizing antibodies decreased, particularly in HCWs over 40 years of age with no history of COVID-19.

In current literature, early immune response for CoronaVac was evaluated in phase trials that found CoronoVac was correlated with high early seroconversion rates in healthy adults (Bayram et al., 2021; Bueno et al., 2021; Dinc et al., 2022; Fadlyana et al., 2021; Uysal et al., 2021). Similarly, we identified this high early antibody response 42 days after the first vaccination of CoronaVac. According to recent studies, the main factors that could influence the vaccine response are young age, female gender, and COVID-19 history before vaccination (Banga Ndzouboukou et al., 2021; Bayram et al., 2021; Dinc et al., 2022; Şenol Akar et al., 2021; Soysal et al., 2021; Uysal et al., 2021). Vaccine immunogenicity is affected by age, as found in previous studies. Although high immunogenicity was demonstrated in phase I-II trials of CoronaVac in the elderly (Wu et al., 2021), this was neither found in our study nor other studies in the literature (Karamese and Tutuncu, 2022). Bayram et al. found the highest early seropositivity between the ages of 18-34 years (Bayram et al., 2021). Bichara et al. observed the frequency of anti-SARS-CoV-2 nAbs was higher in people younger than 40 years of age but significantly decreased with advancing age, supporting our findings (Bichara et al., 2021). In addition, in some studies, COVID-19 history before vaccination was associated with higher early antibody response (21-28 days) after CoronaVac vaccination (Bayram et al., 2021; Dinc et al., 2022; Soysal et al., 2021). In our study, the frequency of the previous history of COVID-19 was higher in the younger group. Therefore, when the comparison groups were matched for these risk factors with propensity matching, age was identified as the main factor influencing early antibody responses in our study.

Long-term antibody responses are still uncertain after CoronaVac vaccination, as most studies evaluate the short-term nAb responses (Bichara et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022; Şenol Akar et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2021; Soysal et al., 2021). When the CoronaVac studies are evaluated, the longest follow-up period is 8 weeks after the second vaccination dose. It is stated that the bAb and nAb responses obtained in these studies remained stable during the follow-up periods. Unlike these studies, we also evaluated long-term antibody response for up to six months at 42, 90, and 180 dpv in our study. However, high bAb and nAb responses on 42 dpv significantly decreased after 90 days, and nAb responses were found at 80.4% at 180 dpv. The bAb and nAb responses decreased significantly at day 180, especially in HCWs over 40 years of age and without a history of COVID-19. This result suggests that CoronaVac-associated antibody response should not be relied upon after 90 days, mainly in these groups.

Our main limitation is that the study was conducted only in a certain occupational group; therefore, the results of our study cannot be generalized to the whole population. The positivity of Immunoglobulin G antibody to SARS‐CoV‐2 at baseline before the vaccine was not evaluated in participants. In this study, only the humoral (nAb) response of the vaccine was revealed, and no information on cellular immunity was presented. Thus our results cannot be considered to provide sufficient evidence of the extent to which this vaccine will protect individuals from the disease.

In conclusion, on 42 dpv, most HCWs developed a significant early antibody response after administering two doses of CoronaVac 28 days apart. Binding and neutralizing antibody responses diminished over time, especially after 90 dpv and especially in HCWs who were not previously infected with SARS-CoV-2 and who were >40 years of age. According to our findings, booster vaccine doses should be planned in terms of age and previous COVID-19 history. These results will help to define immunogenicity and protection of CoronaVac in HCWs who are struggling at the forefront of the pandemic and may guide further approval decisions for booster strategies in COVID-19 vaccination implementations.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The study was funded by the Gazi University Scientific Research Projects Coordination Unit (Grant number TGA-2021-7097).

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants for their generosity and continued support of COVID-19 vaccine research. Our abstract (abstract number 03919) has been accepted as a poster presentation at the 32nd European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) 2022.

References

- Banga Ndzouboukou JL, Zhang YD, Lei Q, Lin XS, Yao ZJ, Fu H, et al. Human IgM and IgG responses to an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Curr Med Sci. 2021;41:1081–1086. doi: 10.1007/s11596-021-2461-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayram A, Demirbakan H, Günel Karadeniz P, Erdoğan M, Koçer I. Quantitation of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 spike protein after two doses of CoronaVac in healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2021;93:5560–5567. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bichara CDA, Queiroz MAF, da Silva Graça Amoras E, Vaz GL, Vallinoto IMVC, Bichara CNC, et al. Assessment of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies post-Coronavac vaccination in the amazon region of brazil. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:1169. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9101169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno SM, Abarca K, González PA, Gálvez NMS, Soto JA, Duarte LF, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in a subgroup of healthy adults in Chile. Clin Infect Dis. 2021:ciab823. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2022. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 Infection) Laboratory Biosafety Guide.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/lab-biosafety-guidelines.html (Accessed 24 Jan 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Daily Sabah. Vaccination drive against coronavirus begins with health care workers in Turkey. https://www.dailysabah.com/turkey/vaccination-drive-against-coronavirus-begins-with-health-care-workers-in-turkey/news, 2021 (Accessed 2022 Jan 24).

- Chen Y, Yin S, Tong X, Tao Y, Ni J, Pan J, et al. Dynamic SARS-CoV-2-specific B-cell and T-cell responses following immunization with an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:410–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damasceno DHP, Amaral AA, Silva CA, Simões E, Silva AC. The impact of Vaccination worldwide on SARS-CoV-2 infection: a review on Vaccine Mechanisms, Results of Clinical Trials, vaccinal Coverage and Interactions with Novel Variants. Curr Med Chem. 2021 doi: 10.2174/0929867328666210902094254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinc HO, Saltoglu N, Can G, Balkan II, Budak B, Ozbey D, et al. Inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine generates high antibody responses in healthcare workers with and without prior infection. Vaccine. 2022;40:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.11.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadlyana E, Rusmil K, Tarigan R, Rahmadi AR, Prodjosoewojo S, Sofiatin Y, et al. A phase III, observer-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: an interim analysis in Indonesia. Vaccine. 2021;39:6520–6528. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henss L, Scholz T, von Rhein C, Wieters I, Borgans F, Eberhardt FJ, et al. Analysis of humoral immune responses in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:56–61. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunsawong T, Fernandez S, Buathong R, Khadthasrima N, Rungrojchareonkit K, Lohachanakul J, et al. Limited and short-lasting virus neutralizing titers induced by inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27:3178–3180. doi: 10.3201/eid2712.211772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamese M, Tutuncu EE. The effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) on antibody response in participants aged 65 years and older. J Med Virol. 2022;94:173–177. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim SSA. Vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 variants: the urgent need for a correlate of protection. Lancet. 2021;397:1263–1264. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00468-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim HX, Arip M, Yahaya AAA, Jazayeri SD, Poppema S, Poh CL. Immunogenicity and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in clinical trials. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2021;26:1286–1304. doi: 10.52586/5024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran L, Chen X, Wang Y, Wu W, Zhang L, Tan X. Risk factors of healthcare workers with coronavirus disease 2019: A retrospective cohort study in a Designated Hospital of Wuhan in China. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2218–2221. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogliani P, Chetta A, Cazzola M, Calzetta L. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies: A network meta-analysis across vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:227. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9030227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati M, Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Agarwal M, Bear J, Burns R, et al. Sequential analysis of binding and neutralizing antibody in COVID-19 convalescent patients at 14 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.793953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadarangani M, Marchant A, Kollmann TR. Immunological mechanisms of vaccine-induced protection against COVID-19 in humans. Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;21:475–484. doi: 10.1038/s41577-021-00578-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Şenol Akar Ş, Akçalı S, Özkaya Y, Gezginci FM, Cengiz Özyurt B, Deniz G, et al. [Factors affecting side effects, seroconversion rates and antibody response after inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in healthcare workers] Mikrobiyol Bul. 2021;55:519–538. doi: 10.5578/mb.20219705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva VO, Yamashiro R, Ahagon CM, de Campos IB, de Oliveira IP, de Oliveira EL, et al. Inhibition of receptor-binding domain-ACE2 interaction after two doses of Sinovac's CoronaVac or AstraZeneca/Oxford's AZD1222 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. J Med Virol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim MR. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:281–282. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soysal A, Gönüllü E, Karabayır N, Alan S, Atıcı S, İ Yıldız, et al. Comparison of immunogenicity and reactogenicity of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in previously SARS-CoV-2 infected and uninfected health care workers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17:3876–3880. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1953344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TR Ministry of Health . 2022. COVID-19 Vaccine National Implementation Strategy.https://covid19asi.saglik.gov.tr/TR-77706/covid-19-asisi-ulusal-uygulama-stratejisi.html (Accessed 24 Jan 2022) [Google Scholar]

- TR Ministry of Health . 2022. COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2 infection) laboratory biosafety guide.https://shgmtetkikdb.saglik.gov.tr/Eklenti/37137/0/covid-19-sars-cov-2-enfeksiyonu-laboratuvar-biyoguvenlik-rehberipdf.pdf (Accessed 10 Feb 2022) [Google Scholar]

- Uysal EB, Gümüş S, Bektöre B, Bozkurt H, Gözalan A. Evaluation of antibody response after COVID-19 vaccination of healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2021 doi: 10.1002/jmv.27420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls AC, Park Y-J, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int, 2022 (Accessed 24 Jan 2022).

- Wu Z, Hu Y, Xu M, Chen Z, Yang W, Jiang Z, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) in healthy adults aged 60 years and older: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:803–812. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30987-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, Li C, Hu Y, Chu K, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18–59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:181–192. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30843-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]