Summary

Paediatric obesity treatment experiences unacceptably high rates of attrition. Few studies have explored parent and child perspectives on dropout. This study sought to capture child and parent experience in treatment and expressed contributors to attrition. Children and parents enrolled in a single family-based weight management programme participated in semi-structured interviews, conducted either upon completion of the first intensive phase of treatment or program dropout. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and coded using a multistage inductive approach. Interviews were obtained from 57 parents and 30 children, nearly equal between ‘completers’ or ‘dropouts’. Five themes emerged: overall positive experience with programme; logistical challenges of participation; improved health; discrepancies between child and parent experience and perception, and importance of structure and expectations of weight loss. Primary reasons given for dropout were time commitment; distance from clinic; missed school and work; lack of dedicated adolescent programme; clinic hours; and stress. Few parents or children expressed dissatisfaction. Children reportedly enjoyed ‘having someone to talk to’ about weight, and spending increased time with family. Children and parents overall reported positive experiences in this weight management programme. Attrition appears more related to logistical issues than low satisfaction. Innovative approaches to help overcome logistical challenges and preserve positive aspects may help in decreasing programme attrition.

Keywords: Attrition, obesity, satisfaction, treatment

Introduction

One-third of children are overweight or obese (1), and severe childhood obesity continues to increase (2). Over $14 billion dollars is spent yearly in the care of children’s weight-related comorbidities and overall healthcare expenditures (3). The United States Preventive Services Task Force found evidence of short-term improvement in the weight of children with obesity who were participating in medium- to high-intensity programmes (4). However, among children in such interventions, many eventually drop out. Reported attrition rates vary from 27% to 73% (5). While the call for effective treatment continues (6,7), addressing significant dropout will be paramount to improving the health of those affected by obesity.

Obesity disproportionately impacts children of lower socioeconomic status and those of racial/ethnic minority background (1,2). Unfortunately, these same children have a higher risk for dropping out of treatment, although studies are mixed (5,8). Diverse causes and contributors of attrition have been identified from existing research to date, likely because of variation between treatment programme and the complexity of families (5). However, in addition to patient and family characteristics associated with dropout (9), programmatic factors also may contribute to attrition. Patient satisfaction and experiences in treatment programmes influence a family’s decision to stop attending treatment programmes, citing perceived quality of care (10), child’s desire to not return (11,12) and overall programme not meeting expectations (11,13,14). Mismatched expectations between parents, children and clinicians are also thought to contribute to attrition (9,13,15,16), specifically regarding the amount and rate of weight loss in the child, misunderstanding programme components, and time commitment for a weight loss programme. However, a systematic review reveals most participants are generally pleased with treatment (17), although there has been very little in-depth investigation of families’ experiences in such interventions. Satisfaction is typically a secondary measure in these studies and only captured by general, non-specific means, such as a single question or brief survey (17).

Despite these newer studies, clinicians are still left with little evidence they can use to increase programme retention and adherence. A recent focus group study explored this in low-income, predominantly Latino families attending a multidisciplinary weight management programme, finding high retention and identifying barriers and facilitators to treatment (18). This study demonstrates potential areas to address to improve retention, including programmes being located in the community, including entire families in activities and taking a skills-based approach lifestyle change (18). As discussed in the review of satisfaction (17), actionable feedback can arise from an additional and concerted focus on dissatisfaction, and the authors of that review suggest employing a patient-centred framework to address the problem.

While studies have attempted to capture the experiences of children and families in treatment (13,19–21), few have undertaken in-depth exploration of satisfaction, and more importantly dissatisfaction. Banks et al. did explore reasons for engaging or not engaging in treatment via a clinical trial (22), finding inclusion of the child and tailoring to family circumstances important; little else, unfortunately, is found in the literature. The overall goal of this study is to capture child and parent perspectives on participating in an obesity treatment programme. The objectives are to determine child and parent expectations of obesity treatment, barriers to participation, overall experience in treatment, and other expressed contributors to attrition.

Materials and methods

Study design

Semi-structured qualitative interviews were conducted with children and parents enrolled in a single family-based weight management programme in North Carolina. Participants (child and parent dyads) were recruited upon starting the weight management programme. Interested participants were enrolled at their intake clinic visit, which typically followed an orientation and group education class, then followed during their time in the programme, monitoring their participation. Parents and children were interviewed after completing the intensive phase of treatment (approximately 4 months long; see Treatment programme), or upon dropping out. Because family and clinic schedules can vary, families could participate in the interview up to six months after completing the initial phase of treatment or after dropping out. However, most interviews occurred within 4–6 weeks. Families were identified as having ‘dropped out’ if they had not attended a clinic visit within the previous four weeks, or had not responded to repeated requests for a follow-up appointment (two phone calls and a mailed letter or email). Interviews typically lasted 30 min or less with parents, and 15 min or less for children. Interviews were conducted by telephone by research staff at a scheduled time, digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and coded using a multistage inductive approach (see Data analysis). Study staff completed intensive training in qualitative interviewing by the senior investigators (JAS). Study protocols, interview questions, and consent procedures were approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Health Institutional Review Board #00019783.

Interview guide

Based upon our previous work (12,17) and using tenets of patient-centred care as a guide (23), we developed interview guides to characterize parent and child experiences in the programme (Table 1). Interviews were developed and tested initially for clarity and comprehension via cognitive interviews (24,25) with volunteers external to the study and in the population of interest (previous or current programme participants), then further refined and developed over time. The interview guide was then reviewed for face-validity by clinicians experienced in obesity treatment and volunteers to determine if questions sufficiently explored aspects of the treatment. Interviews were semi-structured to allow staff to probe for detail, provide clarification, and allow new areas of inquiry to emerge; highly structured interviews may otherwise be too restrictive (26) and not allow for exploration of areas of satisfaction and dissatisfaction.

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview guide

| Questions* | Prompts* |

|---|---|

| Tell me what it was like to be in the programme. | Which members of your family came to clinic visits? Did your family come to any activities outside of clinic? |

| Is your family still in the programme? | If did finish: What helped your family complete the programme? How often did you have to miss appointments? Did you ever consider dropping out? Why? |

| Thinking back to when you first started, do you think your family was ready to be in this programme? Tell me why/why not. | Do you feel you understood what you were getting into? What would have helped your family better prepare for the programme? |

| Tell me how this programme helped your family. | What did you learn in the programme? What did you want to learn in the programme, but didn’t? What changes did your family make as a result of participating in this programme? |

| Tell me how the programme met your expectations. | Was the programme what you thought it would be like? Tell me why/why not. What did you expect to happen in the programme, but didn’t? What happened in the programme that was unexpected? Did the programme meet your family’s needs? Tell me more about that. |

| How have your efforts in the programme ‘paid off,’ or been worth your time? Tell me more about that. | Did you see the results you had hoped to see? What were the results that you hoped to see? |

| How have your child’s efforts in the programme ‘paid off,’ or been worth their time? Tell me more about that. | Did your child see the results they had hoped to see? What were the results he/she hoped to see? |

| What got in the way of or interfered with your family participating in the programme? | How did the programme affect your family negatively or cause your family stress? |

| How did your involvement in the programme affect your work [school] performance? | |

| How did your involvement in the programme affect your child’s school performance? | |

| What could the programme do differently to help your family attend visits or meetings? | |

| What did you like the most about the programme? | |

| What did you like the least? | What are some of the other things you did not like? |

| What were your child’s feelings about the programme? | What did they like about the programme? What did they not like about the programme? |

| How has your child’s health and weight changed after participating in the programme? | |

| How has your family’s health and weight changed after participating in the programme? | |

| Would you participate in Brenner FIT again? Tell me why/why not. | If you were to participate in Brenner FIT again, would you or your family do anything differently? |

Wording of questions slightly different for child interview.

Participants answered a sociodemographic questionnaire to determine parent and child age, race/ethnicity, education level, family structure and insurance coverage. The height of children and parents was measured while standing in socks without shoes using a Seca® Model 240 wall stadiometer (Seca Medical Measuring Systems and Scales, Hamburg, Germany) to the nearest 0.1 cm interval. Measurements were taken three times and averaged. Weight was also measured in socks with no shoes, in regular clothes without coats or sweaters, to the nearest 0.1 kilogram on a Tanita WB 0110 electronic scale (Tokyo, Japan), which was zeroed and calibrated before each measurement. All equipment was regularly calibrated per clinic standards and protocols.

Study participants

The goal was to recruit children and their parents beginning treatment in a tertiary-care obesity treatment programme (see Treatment programme). Parent–child dyads were included if they were English-speaking (all primarily Spanish-speaking patients participate in a parallel programme with a different treatment structure geared to address language barriers (27)), provided assent/consent and met the following criteria: children were between 7 and 18 years old, referred for weight management with a classification of overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 85th percentile for age and sex), and at least one of the child’s primary adult caregivers agreed to participate (mother, father or legal guardian) and planned to attend visits with the child. Exclusion criteria include cognitively or psychologically impaired individuals who cannot provide consent to participate. All children and parents that met inclusion criteria from March 2013 to February 2014 were offered the opportunity to participate; 115 families were eligible to be enrolled in the study, and 28 declined.

Treatment programme

The Brenner FIT (Families In Training) Program is an interdisciplinary, family-based, paediatric weight management clinic within Brenner Children’s Hospital (part of Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center) in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Children between 2 and 18 years old are referred by a physician (typically the primary care provider) for obesity (BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and gender) or overweight (≥85th percentile) with a weight-related comorbidity. Children and their families meet for an intake visit with a paediatrician, family counsellor, dietician, physical therapist and exercise/activity specialist. The entire family is encouraged to attend every aspect of the treatment programme, although only one parent or guardian in attendance is required. After an intake appointment, families participate in biweekly appointments with the family counsellor and dietician for the first 4 months of treatment, then attend a review visit with the physician to assess weight, treatment progress and laboratory studies (eight total visits including intake and physician review visit). Specialized visits with the exercise/activity specialist or physical therapist are scheduled as needed to address pertinent issues. Clinic visits include individualized goal setting around habits the family and clinician have jointly agreed to address, nutrition and activity education, and behavioural counselling to implement changes at home. Motivational interviewing is a key component of treatment (28); family counsellors are trained in cognitive behavioural therapy, parenting support and mindfulness and employ these approaches to assist parents and children in developing healthy habits as the need arises. Clinic visits typically last 45–60 min, and include the parent and child together. Evening cooking classes, child- and family-focused activity programmes, and parenting seminars are offered to participants, but not required. Outside of normal insurance copayments, there is no additional costs to family, with additional resources (group classes, exercise/activity specialist) paid for through philanthropy or by the hospital. Further details of the Brenner FIT programme have been described previously (12,29–31).

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim from recordings into Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The interviews were then analysed using a thematic analysis approach (32). Thematic analysis provides a systematic method for coding and analysing qualitative data, and is useful for exploratory evaluation of explicit and covert meanings in a text, identifying important aspects for study and interpretation. In this study, analysis was used to interpret interviews and thus conceptualize experiences of parents and children in obesity treatment. This analytic approach is a systematic process that goes beyond preconceived hypotheses and allows themes and ideas to emerge from the data organically.

To systematically analyse transcripts, investigators developed a common coding system by separately reading and re-reading transcripts to identify potential codes. Codes were developed based on review of 10 transcripts by two investigators (JAS, SBM), first separately and then jointly. Transcripts were re-reviewed with a third investigator (MBI) to refine the common coding library and data dictionary. Throughout this iterative process, codes were modified as appropriate with repeated comparisons and revisions. Once the common coding system was developed, all transcripts were analysed and initially coded by one investigator (SBM), then reviewed by another (JAS). Discrepancies in coding schema were adjudicated through discussion. Representative quotes were captured. Transcript codes were grouped into similar concepts and broad categories. From this schema, themes and sub-themes (and notable quotes corresponding to each sub-theme) were developed and interpreted by the investigators, with ongoing comparisons, revisions, and interpretations.

Results

Eighty-seven parent–child dyads (families) initially enrolled in the study. The participating parent was typically the mother. The sample had a majority of White participants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | n = 87 |

|---|---|

| Child age, years, mean ± SD | 11.9 years ± 2.51 |

| Female child gender | 65% |

| Child BMI, kg m−2, mean ± SD | 34 ± 8.35 |

| Child BMI z score, mean ± SD | 2.36 ± 0.355 |

| Child race/ethnicity | |

| Latino | 1% |

| Non-Latino African-American | 40% |

| Non-Latino White | 54% |

| Asian | 1% |

| American Indian | 1% |

| Other | 3% |

| Parent age, years, mean ± SD | 41.8 ± 8.08 |

| Parent BMI, kg m−2, mean ± SD | 37.9 ± 9.76 |

| Parent female gender | 93% |

| Parent race/ethnicity | |

| Latino | 2.3% |

| Non-Latino African-American | 38.8% |

| Non-Latino White | 57.7% |

| Asian | 1% |

| Other | 3% |

| Household composition | |

| Dual parents | 60% |

| Single parent | 40% |

| Insurance, Medicaid | 33.7% |

| Highest educational attainment, parent | |

| High graduate or less | 15% |

| Some college | 37% |

| College graduate or higher | 36% |

| Number of children in home, mean | 2.08 ± 1.18 |

Attrition

Sixty-three percent of patients/families dropped out before completing the first intensive, 4 months of treatment. There were no significant sociodemographic differences between those who completed and those who dropped out, except that children who dropped out had higher BMI z scores by t-test (2.45 vs. 2.21, P < 0.01, data not shown).

Interviews

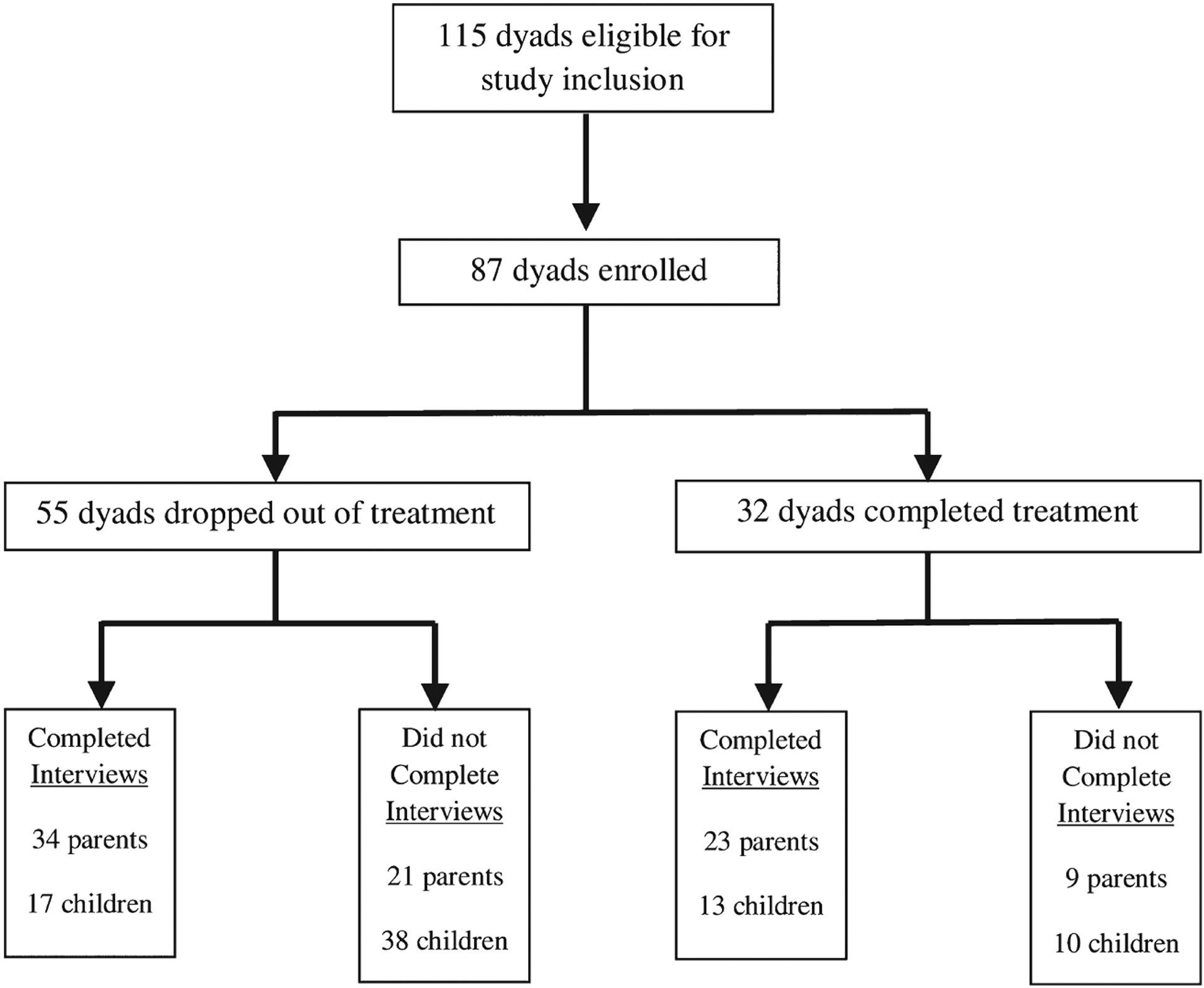

A total of 57 parents and 30 children participated in interviews (66% and 34% of the total sample, respectively) (Fig. 1). Proportionally, 62% of parents who dropped out and 72% who completed treatment participated in interviews. Of children, 31% who dropped out and 41% who completed treatment participated in interviews. Interviews were not completed because of non-response to requests for interviews (three phone messages and a letter) or not answering the phone at the scheduled interview time. No parent refused the interview when contacted. Of the 57 parents who completed the interview, 27 had children who were not interviewed, either because the child refused to complete the interview or did not answer the phone at the scheduled interview time. Parents who participated in interviews were heavier (mean BMI 39.6 kg m−2 vs. 34.8, P < 0.05), and were more educated (P < 0.05) than parents who did not participate in an interview. Children who participated in interviews were older (mean age 12.8 years vs. 11.4 years, P = 0.01) than those who did not participate.

Figure 1.

Recruitment, attrition and interview completion.

Themes

Overall, there was very little difference in comparing comments of those who dropped out and those that completed treatment. For those that did drop out, a lack of weight loss, desire for more structure in treatment to achieve weight loss and absence of an adolescent-specific programme were mentioned. Five major themes emerged from the interviews: overall positive experience with programme; logistical challenges of participation; improved health of family; discrepancies between child and parent experience and perception; and importance of structure and expectations for weight loss (Table 3).

Table 3.

Themes and sub-themes with representative quotes

| Theme | Sub-theme | Representative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Positive experience with programme | Classes | ‘… just being able to engage and being able to meet other families with similar things going on. With the cooking class … there was a lot of other families there and it was just nice to be around other people that were kind of in the same boat.’ |

| Staff support | ‘The folks in the program have just been so encouraging and said you’ve been fine given the circumstances and it’s just important to not let that discourage you and to just keep going. That has helped a lot.’ | |

| Individualized/holistic approach | ‘While we [were] sent there because of certain concerns our doctors had, they treated us with total body care and that really meant a lot to me.’ | |

| Approachability of staff | ‘It’s nice having someone to talk to who knows things and being able to ask them questions and stuff.’ | |

| Logistical challenges of participation | Time | ‘The only issues I’ve had with the program is the time commitment. It is a big time commitment … Another thing is I find it hard myself to make some of the activities, the family activities, because I do work and a lot of them are 5:30 pm and that sort of thing and I live further away.’ |

| Travel | ‘I think for my family the hardest part about it is the distance. We live about an hour and 45 min from the program and that was challenging. It limited the things that we could participate in. So we would come for appointments but then it wasn’t really feasible a lot of times to come to any of the different classes or activities or different things that were offered periodically because it was just so far.’ | |

| Missed school | ‘… during the school year it gets challenging and once my older daughter was really into high school, missing school and getting out early were problematic. The school … wouldn’t excuse the time away … once we got further into high school I didn’t realize just how difficult and how rigid they were going to be about you ever missing school even with a doctor’s note.’ | |

| Missed work | ‘It made it difficult to get some of my work done. I had to miss a lot of work and that sort of thing but I adjusted for it.’ | |

| Lack of teen focused programme | ‘My daughter was not interested any longer. She thought that it was too many little kids and not enough kids her age so she just became disinterested in what was going on.’ | |

| Parking | ‘It was difficult for our family at the time to come to the hospital and pay the parking fees and that kind of thing. And try to get there on time because the hospital is just not a real user friendly place to visit I guess.’ | |

| Improved health | With and without weight loss | With weight loss: ‘When she’s with [the program] she’s doing more, she’s more active. She was losing weight and everything when we were going consistently …’ |

| Without weight loss: ‘But I think the thing that they probably did get out of it that I didn’t think about beforehand because I was more focused just on weight loss was healthy ideas about themselves - food, body image …’ | ||

| Improved health behaviours | ‘We have made some good lifestyle changes that hopefully will help us through the rest of our lives.’ | |

| Improved confidence | ‘A lot of the program has benefitted him … the activities and the things that he participated in actually brought his self-esteem up and broadened his horizons of what he can do physically.’ | |

| Parent and child differences | Desire for structured treatment (parent) | ‘It’s been less successful than we hoped. We haven’t had a lot of results. It’s been more drawn out and less specific than we had hoped. But I can’t say that it’s been a negative experience. It’s been generally positive but not very actually productive.’ |

| Family time (child) | ‘It’s brought us together more as a family. It’s made opportunities for us to do things as a family activity.’ | |

| Prepared for clinic (parent) | ‘I think that they did a really good job preparing. There were phone conversations before we ever came and there was an Orientation - there was a lot of information beforehand. I think that they did a good job preparing us for the program and what was to be expected and that sort of thing.’ | |

| Importance of structure and expectations of weight loss | Concrete guidance on behaviour changes | ‘I think accountability on some things helps people … I can lose weight better with [another program] because there’s somebody else watching the scale that I have to be held accountable to. I think it’s kind of the same even in changing habits. There needs to be some sort of accountability.’ |

| Greater weight loss and weight loss expectations | ‘I mean obviously it would have been great if my girls had sustained weight loss from participating in the program and we didn’t really see that happen.’ |

Positive experiences

Nearly all participants had something positive to say about their programme experience. This was true for parents and children, dropouts and completers.

Classes.

Classes were highly valued by all participants. Participants enjoyed learning about healthy behaviours in a class setting. Typically, parents valued the classes because of subsequent outcomes. For example, they appreciated tangible dietary changes that their children implemented after attending a nutrition class. The children valued time spent as a family during the classes, and enjoyed attending classes with their family and learning together.

Staff support.

Participants valued having someone to listen to them talk about health behaviours, family relationships and daily situations. Parents and children found programme staff to be positive, supportive and helpful. Children frequently mentioned they enjoyed having ‘someone to talk to’ about their weight and health.

Individualized and holistic treatment approach.

Both parents and children appreciated a holistic approach to their treatment, including interactions with doctors, therapists, counsellors and educators. It was important to participants to feel as if the treatment that they received was individualized and specifically created for them. Parents valued the time spent working to set family-specific goals and do other activities that acknowledged the uniqueness of participants and allowed them to design their own plan.

Approachability of staff.

Children and parents expressed comfort in discussing topics with professionals who seemed experienced in weight management.

Logistical challenges

Barriers to programme participation were frequently discussed in detail by participants.

Time.

The time commitment was a deterrent to participation in the programme. A number of parents stated that the programme commitment was sometimes too great to integrate into an already busy family schedule. Stress and family schedule were mentioned by many participants.

Travel.

Distance from the clinic was another reason for dropout or difficulty attending the programme, mentioned by both parents and children as a frustration. Commute times in addition to time spent in clinic added stress to participant schedules.

Missed school.

Programme participation was perceived as more difficult during the school year. Older participants (high school age) especially struggled when they needed to regularly miss school to attend appointments. When asked, no participants explicitly stated that the programme negatively impacted school performance, but acknowledged that they missed a lot of school time.

Missed work.

Parents’ conflicting work schedules were a common reason for rescheduling of clinic visits, and contributed to dropout as well. Parents cited this factor as one of their main frustrations, and recommended extended clinic hours to accommodate working parents.

Lack of teen programming.

Older children and their parents expressed frustration with a lack of programming for teens. Thus, they felt less engaged and excited about attending programme activities.

Parking.

Parking and general hospital navigation were logistical problems for many participants. Some felt parking was difficult, expensive and distant from the clinic location. Clinic parking was often inconvenient and for some families, an expense that they could not afford, ranging from $1.50 to $5, depending on duration of visit. Additionally, it was often hard for participants to navigate the hospital and clinic.

Improved health

One of the most positive outcomes of the programme for many families was improved health, which did not necessarily depend on weight loss. Both parents and children mentioned better nutritional habits, more exercise and other positive health behaviours. Some participants and their families did also experience weight loss and mentioned this as a benefit as well.

With and without weight loss.

Parents often stated that they saw health improvements in their children, whether they were losing weight or not. Often they desired weight loss, but also saw benefits in behaviour changes and nutritional habits that contributed to better well-being without tangible weight loss.

Improved health behaviours.

Both parents and children often noted improvements in their own and their family’s health habits. This included dietary changes, less sedentary behaviour, meal planning, healthy snacking, increased physical activity and others.

Improved confidence in child.

A number of parents perceived improved self-esteem and self-confidence in their children. This confidence came as a result of both health and weight changes, and classes within the programme that targeted confidence building.

Parent and child differences

Children and parents were interviewed separately, and there were differences in response between them.

Parent’s desire for more structured treatment.

Nearly half of parents (28 out of the 57 interviewed) expressed a desire for more structure in the programme; children rarely mentioned that they desired more structure. They asked to be told ‘specifically what to do, and how to do it’, rather than designing goals to work towards as a family.

Children valued family time.

Children often mentioned they valued family time. They provided concrete examples such as meal planning, goal setting and family meals. They placed value on the increased family time, and perceived it as one of the most important outcomes of the programme to them. Parents rarely mentioned this point during interviews.

Parents universally felt prepared for clinic.

Parents often stated that they knew what to expect when joining the programme, and that they felt prepared. Children more often said that they were not sure about the programme or were unclear on what to expect when starting. Parents sometimes stated that their child was unmotivated or uninterested in the programme.

Importance of structure and expectations for weight loss

While generally satisfied and pleased with the programme, many parents expressed a desire for greater structure, hoping that it would lead to better outcomes.

Concrete guidance on behaviour change.

Parents wanted more instruction on how to implement behaviour change plans at home, focusing on how to instigate weight loss. Parents felt greater weight loss could be achieved by more rigorous and structured approaches.

Greater weight loss and expectations for weight loss.

Many participants who dropped out stated that a lack of significant weight loss was a main contributing factor to their decision to stop attending the programme. Parents and children expressed a desire for rapid weight loss and stopped attending clinic visits and other activities when weight loss goals were not achieved. By this metric, they then perceived the programme to be ineffective.

Reasons for dropout

Parents and children mentioned a variety of reasons for not completing the programme. These included time commitment, travel distance from clinic, missed time from work and school, incompatible clinic hours, family stress, and programme dissatisfaction. For the most part, parents felt that general logistical challenges contributed more to attrition than programme dissatisfaction. Parent and child participants often stated that it was difficult for their family to participate, and that is why they left the programme. Programme dissatisfaction for children and parents included absence of an adolescent-specific programme, lack of weight loss and desire for more treatment structure. Overall though, few parents or children expressed specific dissatisfaction with the programme, staff or experience. Only five out of 57 parents replied that they would not participate in the treatment programme again. Most said they would if barriers were addressed such as clinic hours and locations, or if they felt their child could lose more weight.

Suggestions for improvement

The most commonly suggested improvement was for additional clinic locations in the community. Parents remarked that having a clinic location closer to their home would help with attendance. Other suggestions were expanded clinic hours to include evenings, assistance with transportation to clinic, free or reduced-price parking, developing an adolescent-specific programme and more prominent advertising of programmes outside of the clinic.

In response to the question ‘if you could design a weight management programme for your family, what would it look like?’ parents and children had varied answers. Overall, parents commented that designing a weight management programme for their family was a difficult task, as the problem of childhood obesity was overwhelming. Parents and children had similar responses to what a programme should include making the programme realistic and manageable for their family; opportunities for physical activity and exercise for the child and for the entire family; having designated times for family goal-setting and spending time together as a family; guidance in establishing or learning to cook family meals, and structured classes about nutrition (e.g. portion control, meal planning).

Discussion

This study provides insight into the satisfaction and dissatisfaction of families in a paediatric obesity treatment programme. Despite families having an overall positive experience in our programme, there was a high attrition rate (63%). This exploration of the family viewpoint did provide valuable insight into their experience and perceived contributors. Parents and children identified outcomes of importance to them that have not been previously recognized. Children highly valued how the programme resulted in more time together as a family, particularly in scheduled activities such as cooking and meal planning. Parents reported improvement in overall health behaviours and well-being, such as improved self-esteem and self-confidence, which they appeared to value greatly. Logistical problems with regularly attending clinic visits and educational classes are a significant challenge to programme participation. Parents expressed a desire for greater weight loss, which was the apparent primary contributor to dissatisfaction with the programme. They felt that having more structure would help the child and family achieve greater weight loss.

Our results confirm and expand what has been found in the few other studies conducted in this area (22,33). As summarized in the systematic review of satisfaction and obesity treatment, families appreciate the efforts of obesity programmes and their clinicians, as most that dropped out were willing to return (17). Our programme featured individual clinic visits and educational classes, and families liked aspects of both the personalized nature of clinic visits and the group component and content of classes. This can be a difficult balance for treatment programmes, as group visits allow for more cost-effective treatment (34) and likely may be more convenient for families. Yet, group programmes may not allow relationships to form between clinicians and families, which participants reportedly valued in this study and others (9,16). Similar to a study of four obesity treatment programmes in primary care and community-based settings (9), parents perceived improvement in their children’s health and overall well-being, citing enhanced self-confidence and self-esteem as being important outcomes. Banks et al.’s study in the UK had similar results of high satisfaction, capturing perspectives of children and adults (22). US families in this study had similar comments and satisfaction, regardless of attrition; this study highlights differences between child and adult, suggestions for improvement, and desire for more structure to treatment to achieve weight loss.

Consistent with other studies of attrition (10–13,15), logistical challenges continue to be a major contributor to dropout. Parents relayed their opinions on methods to overcome these challenges, highlighting the establishment of additional clinic locations, development of adolescent-specific programmes and having a more structured clinical treatment approach. Expanding evening and weekend offerings would likely have administrative limitations at some institutions, but could be implemented as a means to improve retention. However, a recent randomized controlled trial qualitatively investigated attrition between a primary-care and hospital-based clinic in the UK. Despite the difference in locations, with hospital-based programmes presumably having greater logistical challenges, there were no differences in attrition or satisfaction between sites (22). Therefore, innovative approaches to treatment, aside from addressing logistical issues of place and time, must be considered as an attempt to improve outcomes. In-home treatment (35), internet-based programmes (36,37), telemedicine (38) and school-based interventions (39) all hold potential. Engaging families in a patient-centred manner to address such issues has shown potential (40) and may yield novel approaches not yet tested. Clinicians and programmes can implement front-line changes based on these findings as well. Families’ perceptions of important outcomes can be used to increase retention (9), particularly children valuing time spent with family in the programme. Programmes can add more family-inclusive activities, such as activities that encourage cooking and playing together as families, or simply spending more time together.

Other research has demonstrated that a child’s desire to leave a treatment programme was influential in the family’s decision to drop out (11,12). Thus, a focus on children’s value of increased family time potentially could improve retention and outcomes if families’ engagement increases. Parents also valued non-weight-related outcomes, such as improved self-esteem and confidence, similar to recent findings of a treatment programme focused on low-income families (18). These results suggest that measurement and improvement in these areas also could impact family retention. Laboratory studies, waist circumference, behaviour change or measures of fitness could show parents tangible improvement in well-being. Developing age-appropriate programming, such as adolescent-specific approaches requested by participants in this study, may be promising. Greater exploration of family function around health habits may reveal new opportunities for intervention, in addition to dropout prevention (41).

There are limitations to this study. Qualitative investigation does not provide verifiable or measurable results, and further quantitative exploration is often needed. However, our approaches are appropriate to explore complex and highly personal aspects of individual behaviour and health. Qualitative research allows evaluation and synthesis of participant perspectives, particularly with a large number of families participating in interviews. This study was only conducted in one treatment programme in North Carolina, which limits generalizability and transferability to other patient populations and treatment programmes. Lack of generalizability is not usually seen as a limitation of qualitative investigations (32), but results should be applied with caution to other populations and treatment settings. Another limitation is the inability to capture the perspective of all participants, including more than half of children recruited. We believe a representative sample was obtained between participants who completed and who dropped out, but there were some differences between those who did and did not participate in interviews.

Weight management was well received by participants in this family-based programme. Attrition appears related more to logistical issues than dissatisfaction with treatment. Parents desired greater weight loss, but also identified non-weight-related outcomes as important; children valued time together as a family. Innovative approaches to help overcome logistical challenges of treatment while preserving positive aspects may help to decrease attrition.

What is already known about this subject.

Paediatric obesity is known to have very high rates of dropout.

Logistical concerns affect family participation in treatment.

Unknown if child and parent satisfaction with treatment programme contributes to attrition.

What this study adds.

Overall, children and parents satisfied with this family-based treatment programme.

Parents desire more structure as a means to increase child weight loss, but report logistical concerns as primary reasons for dropout.

Children value ‘having someone to talk with’ about their weight, and enjoy treatment resulting in increased time with family.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Courtney Giannini for her assistance in the conduct of this study, and Karen Klein (Biomedical Research Services and Administration, Wake Forest School of Medicine) for editing the manuscript.

Funding

Dr. Skelton was supported in part through NICHD/NIH Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23 HD061597).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

No conflict of interest was declared.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011–2012. JAMA 2014; 311: 806–814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skinner AC, Skelton JA. Prevalence and trends in obesity and severe obesity among children in the United States, 1999–2012. JAMA Pediatr 2014; 168: 561–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cawley J The economics of childhood obesity. Health Aff 2010; 29: 364–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitlock EP, O’Connor EA, Williams SB, Beil TL, Lutz KW. Effectiveness of weight management interventions in children: a targeted systematic review for the USPSTF. Pediatrics 2010; 125: e396–e418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skelton JA, Beech BM. Attrition in paediatric weight management: a review of the literature and new directions. Obes Rev 2011; 12: e273–e281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniels SR, Kelly AS. Pediatric severe obesity: time to establish serious treatments for a serious disease. Child Obes 2014; 10: 283–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson TN. Treating pediatric obesity: generating the evidence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008; 162: 1191–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haemer MA, Ranade D, Baron AE, Krebs NF. A clinical model of obesity treatment is more effective in preschoolers and Spanish speaking families. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013; 21: 1004–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giannini CG, Irby MB, Skelton JA. Caregiver expectations of family-based pediatric obesity treatment. Am J Health Behav 2015; 39: 451–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cote MP, Byczkowski T, Kotagal U et al. Service quality and attrition: an examination of a pediatric obesity program. Int J Qual Health Care 2004; 16: 165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barlow SE, Ohlemeyer CL. Parent reasons for nonreturn to a pediatric weight management program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2006; 45: 355–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skelton JA, Goff D, Ip E, Beech BM. Attrition in a multidisciplinary pediatric weight management clinic. Child Obes 2011; 7: 185–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hampl S, Demeule M, Eneli I et al. Parent perspectives on attrition from tertiary care pediatric weight management programs. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2013; 52: 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitscha CE, Brunet K, Farmer A, Mager DR. Reasons for non-return to a pediatric weight management program. Can J Diet Pract Res 2009; 70: 89–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hampl S, Paves H, Laubscher K, Eneli I. Patient engagement and attrition in pediatric obesity clinics and programs: results and recommendations. Pediatrics 2011; 128(Suppl. 2): S59–S64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skelton JA, Irby MB, Beech BM, Rhodes SD. Attrition and family participation in obesity treatment programs: clinicians’ perceptions. Acad Pediatr 2012; 12: 420–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skelton JA, Irby MB, Geiger AM. A systematic review of satisfaction and pediatric obesity treatment: new avenues for addressing attrition. J Healthc Qual 2014; 36: 5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cason-Wilkerson R, Goldberg S, Albright K, Allison M, Haemer M. Factors influencing healthy lifestyle changes: a qualitative look at low-income families engaged in treatment for overweight children. Child Obes 2015; 11: 170–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart L, Chapple J, Hughes AR, Poustie V, Reilly JJ. Parents’ journey through treatment for their child’s obesity: a qualitative study. Arch Dis Child 2008; 93: 35–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sallinen Gaffka BJ, Frank M, Hampl S, Santos M, Rhodes ET. Parents and pediatric weight management attrition: experiences and recommendations. Child Obes 2013; 9: 409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woolford SJ, Sallinen BJ, Schaffer S, Clark SJ. Eat, play, love: adolescent and parent perceptions of the components of a multidisciplinary weight management program. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012; 51: 678–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banks J, Cramer C, Sharp DJ, Shiled JPH, Turner KM. Identifying families’ reasons for engaging or not engaging with childhood obesity services: a qualitative study. J Child Health Care 2014; 18: 101–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Medicine Io. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academies Press: Washington, D.C., 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A ‘How To’ Guide. 1999. [WWW document]. URL http://hkr.se/pagefiles/35002/gordonwillis.pdf (accessed October 2014).

- 25.Willis GB, Royston P, Bercini D. The use of verbal report methods in the development and testing of survey questionnaires. Appl Cogn Psychol 1991; 5: 251–267. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alasuutari P An Invitation to Social Research, Vol. 143–145. Sage: London, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guzman A, Irby MB, Pulgar C, Skelton JA. Adapting a tertiary-care pediatric weight management clinic to better reach Spanish-speaking families. J Immigr Minor Health 2012; 14: 512–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Irby M, Kaplan S, Garner-Edwards D, Kolbash S, Skelton JA. Motivational interviewing in a family-based pediatric obesity program: a case study. Fam Syst Health 2010; 28: 236–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skelton JA, Irby M, Beech BM. Bridging the gap between family-based treatment and family-based research in childhood obesity. Child Obes 2011; 7: 323–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown CL, Irby MB, Houle TT, Skelton JA. Family-based obesity treatment in children with disabilities. Acad Pediatr 2015; 15: 197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Irby MB, Kolbash S, Garner-Edwards D, Skelton JA. Pediatric obesity treatment in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: a case series and review of the literature. Infant, Child Adolesc Nutr 2012; 4: 215–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing Qualitative Data: Systematic Approaches. Sage Publications: Washington, D.C., 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schalkwijk AA, Bot SD, de Vries L et al. Perspectives of obese children and their parents on lifestyle behavior change: a qualitative study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015; 12: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldfield GS, Epstein LH, Kilanowski CK, Paluch RA, Kogut-Bossler B. Cost-effectiveness of group and mixed family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1843–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Showell NN, Fawole O, Segal J et al. A systematic review of home-based childhood obesity prevention studies. Pediatrics 2013; 132: e193–e200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sousa P, Fonseca H, Gaspar P, Gaspar F. Usability of an internet-based platform (Next.Step) for adolescent weight management. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2015; 91: 68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sousa P, Fonseca H, Gaspar P, Gaspar F. Controlled trial of an Internet-based intervention for overweight teens (Next.Step): effectiveness analysis. Eur J Pediatr 2015; 91: 68–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen GM, Irby MB, Boles K, Jordan C, Skelton JA. Telemedicine and pediatric obesity treatment: review of the literature and lessons learned. Clin Obes 2012; 2: 103–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lazorick S, Crawford Y, Gilbird A et al. Long-term obesity prevention and the Motivating Adolescents with Technology to CHOOSE Health program. Child Obes 2014; 10: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Li K, Kranz S, Lawson HA. A childhood obesity intervention developed by families for families: results from a pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2013; 10: 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skelton JA, Buehler C, Irby MB, Grzywacz JG. Where are family theories in family-based obesity treatment?: conceptualizing the study of families in pediatric weight management. Int J Obes (Lond) 2012; 36: 891–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]