Abstract

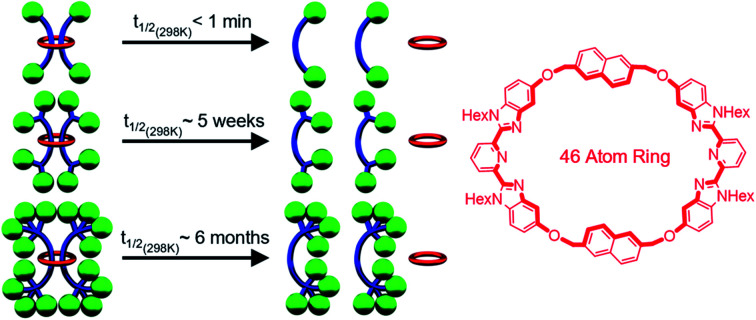

Ring size is a critically important parameter in many interlocked molecules as it directly impacts many of the unique molecular motions that they exhibit. Reported herein are studies using one of the largest macrocycles reported to date to synthesize doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes. A large ditopic 46 atom macrocycle containing two 2,6-bis(N-alkyl-benzimidazolyl)pyridine ligands has been used to synthesize several metastable doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes in high yield (65–75% isolated) via metal templating. Macrocycle and linear thread components were synthesized and self-assembled upon addition of iron(ii) ions to form the doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxanes that could be subsequently stoppered using azide–alkyne cycloaddition chemistry. Following demetallation with base, these doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes were fully characterized utilizing a variety of NMR spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, size-exclusion chromatography, and all-atom simulation techniques. Critical to the success of accessing a metastable [3]rotaxane with such a large macrocycle was the nature of the stopper group employed. By varying the size of the stopper group it was possible to access metastable [3]rotaxanes with stabilities in deuterated chloroform ranging from a half-life of <1 minute to ca. 6 months at room temperature potentially opening the door to interlocked materials with controllable degradation rates.

Multiple metastable doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes using a large 46 atom ring were prepared and fully characterized. Varying the stopper group size gave a range of interlocked stabilities in CDCl3 from a half-life of <1 minute to ca. 6 months.

Introduction

Even after multiple decades of research, mechanically interlocked molecules (MIMs) continue to inspire chemists and engineers alike on account of their unique interlocked structure and properties.1–5 Specifically, the synthesis and study of rotaxanes, which are interlocked molecules comprised of dumbbell and ring components, account for over two thirds of all publications involving MIMs.6,7 This popularity, which is in part a result of their synthetic accessibility, has resulted in their use in a wide range of applications that include molecular machines, catalysis, molecular computing, and drug delivery, to name a few.8–15 The simplest and most-investigated version of a rotaxane is the singly threaded [2]rotaxane comprised of one macrocycle component kinetically trapped between the large stopper groups of the dumbbell-like component.16,17 However, as the field continues to grow, there is increasing interest in looking towards higher order rotaxanes6,18 (containing more rings, more dumbbells, or both) and their corresponding mechanically interlocked polymers (MIPs).19,20 This has led to complex architectures capable of advanced function such as molecular elevators,21,22 artificial molecular muscles,23,24 molecular pulleys,25 and more.9 In addition, polyrotaxane-based materials, such as slide-ring gels,26,27 have attracted great interest on account of their unique property profiles which have, for example, been commercialized into scratch-resistant coatings.28 In these materials (and MIPs more broadly), macrocycle size variation has emerged as an important design parameter19,29–31 with preliminary studies indicating that fluorescence quenching32 and viscoelastic relaxation dynamics33 can be tuned by controlling the size of the ring component. As such, there is interest in accessing interlocked polymeric systems with larger rings for further tunability. However, in the literature there appears to be an upper boundary in the size of the macrocycles (around 40 atoms) that are used to synthesize the majority of rotaxane-like structures.

Synthetic efforts targeted at accessing rotaxanes with bigger rings have revealed that even relatively small increases in macrocycle size necessitate dramatic increases in stopper group size.34,35 Furthermore, investigations into the interlocked stability of rotaxanes have shown that depending on the relative size of the stopper and ring,36–41 some of these interlocked structures are in fact environmentally-dependent metastable rotaxanes,42 in which the macrocycle is able to slowly slip over the stoppering moiety resulting in the non-interlocked components. Controlling environmental conditions such as temperature, pH, and solvent polarity combined with this unique feature of metastable rotaxanes has been utilized in controlled release applications.43–45 Furthermore, metastable rotaxanes have been employed in the development of molecular pumps,46–49 chemical protection,50–52 modifiable molecular containers,53 and bacterial imaging probes.54

All of the rotaxane materials discussed above are based on singly-threaded architectures. Threading multiple dumbbells within the same macrocyclic cavity offers the unique ability to ensure their close spatial proximity allowing for their physical and optical properties to be influenced.6 However, doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes have proven extremely challenging from a synthetic standpoint6 leading to only limited exploration of the corresponding MIPs and higher order rotaxanes.55–58 As larger macrocycles are typically required to incorporate multiple threads, the difficulty, at least in part, stems from ensuring that the stopper size is large enough to stabilize the interlocked architecture. For example, work by Leigh and coworkers showed that it was possible to access a stable [3]rotaxane with a 38 atom macrocycle, however changing the ring size by just one atom (to 39 atoms) resulted in no isolatable interlocked product.59 As a result, molecular doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes where both threads exist in a single ring have seen limited high yielding syntheses with reported isolated yields between 6 and 70%.59–66 In addition, the largest reported macrocycle size used to access such a [3]rotaxane is 41 atoms and the resulting interlocked compound exhibited slow slippage in solution (t1/2 ∼ 1 week at 298 K in dichloromethane).62 With the goal of accessing multiply threaded higher ordered MIMs and MIPs and developing a better understanding of how to control the stability (and therefore utility) of such structures, reported herein are studies aimed at targeting doubly threaded metastable [3]rotaxanes with a large 46 atom macrocycle.

While a variety of supramolecular templating methods have been utilized to synthesize rotaxanes (such as π–π stacking,67 hydrogen bonding,68 hydrophobic interactions,69 and anion recognition70), it is metal ion templating71–73 (both passive74–76 and active77–79) that has proven to be one of the most popular routes for accessing doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes. While a wide range of ligands have been explored to access mechanically interlocked structures,72 the terdentate ligand, 2,6-bis(N-alkyl-benzimidazolyl)pyridine (Bip), has a number of attractive features including a flexible and scalable synthesis combined with the ability to tailor its solubility by altering its N-alkyl moieties.80 It has also been used to access metallosupramolecular assemblies and polymers,81–85 [2]catenates,86 [3]catenates,87 and poly[n]catenanes88,89via metal ion coordination. As such, this study utilizes Bip/metal ion templating to access isolatable doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes (Fig. 1a) using one of the largest (46-atom) macrocycles employed to date in rotaxane synthesis and explores how tuning the size of the stoppering group impacts their kinetic stability.

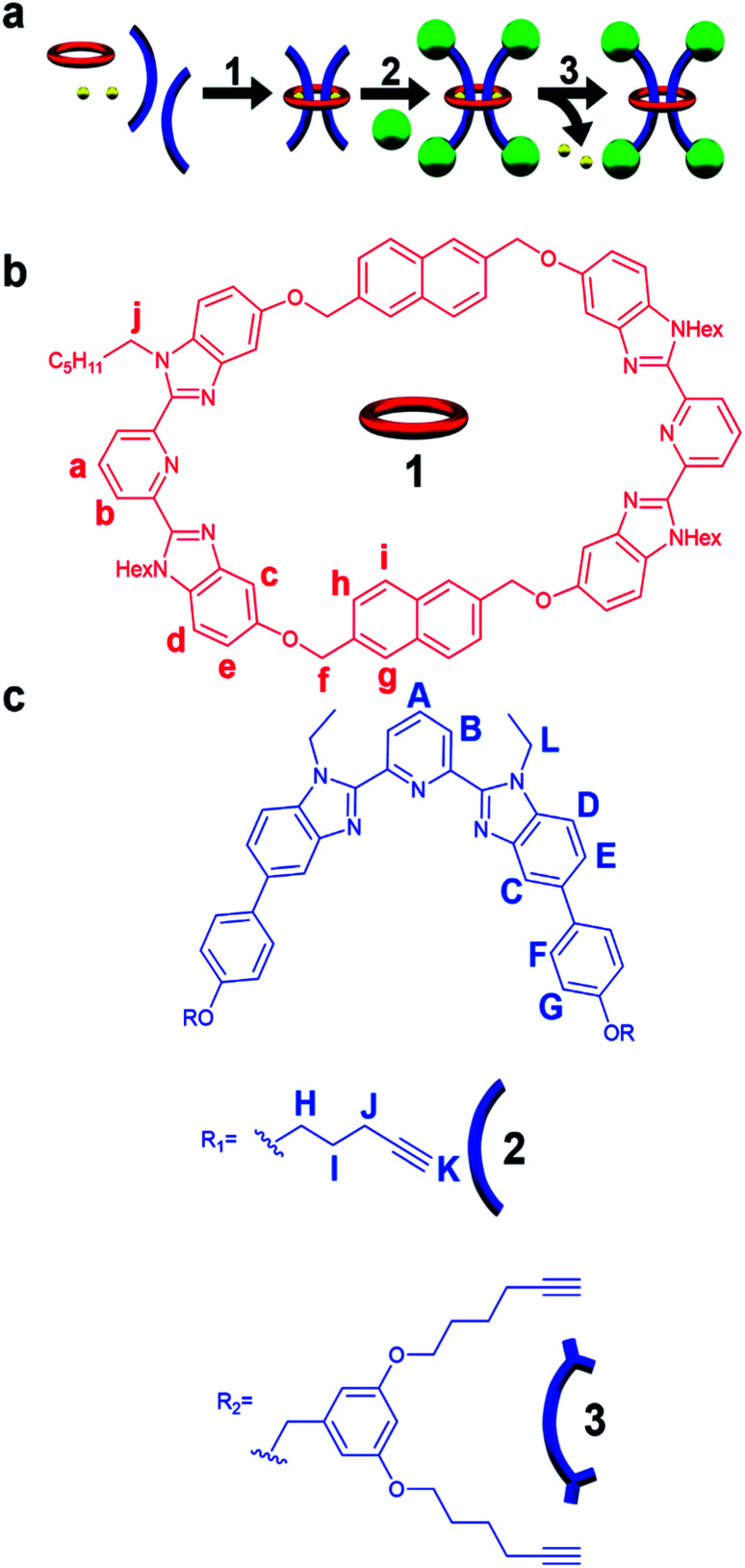

Fig. 1. (a) Cartoon scheme of the doubly threaded [3]rotaxane synthesis that involves metalation of the components with Fe(ii) (step 1) followed by addition of the stopper group (step 2) and finally demetallation (step 3). (b) Chemical structure of the 2,6-bis(N-alkyl-benzimidazolyl)pyridine (Bip) containing 46 atom macrocycle 1 and (c) the Bip-containing thread components 2 and 3, 1H NMR assignments indicated.

Results and discussion

Metal-directed self-assembly of the macrocycle with two thread-like components followed by stoppering and demetallation was used to access the [3]rotaxanes (Fig. 1a). The large ditopic Bip-containing macrocycle 1 (Fig. 1b) and the Bip-containing linear thread components 2 and 3 (Fig. 1c) were synthesized and fully characterized from their corresponding bis-phenolic Bip derivatives80,87via Williamson ether synthesis (see ESI, Schemes S1–S6†). 1 is a 46-membered macrocycle incorporating two Bip ligands joined by 2,6-bis(methylene)naphthalene linking units. The rigidity present in the macrocycle was designed to prevent both Bip ligands in 1 binding to the same metal ion and ensure that the only way for these ligands to form 2 : 1 Bip : metal complexes is in the presence of the thread (as confirmed by a UV titration experiment, see ESI, Fig. S1†). The N-hexyl substituted Bip ligand in 1 was chosen to aid solubility of the macrocycle, while the thread components 2 and 3 contain an N-ethyl substituted Bip ligand to minimize steric repulsion between the thread molecules when both are bound within macrocycle 1. Components 2 and 3 were end functionalized with terminal alkyne groups (two alkyne moieties in 2 and four alkyne moieties in 3) in order to allow azide–alkyne cycloaddition90,91 as the stoppering chemistry.

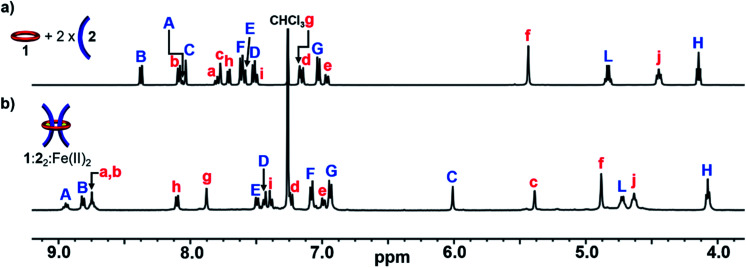

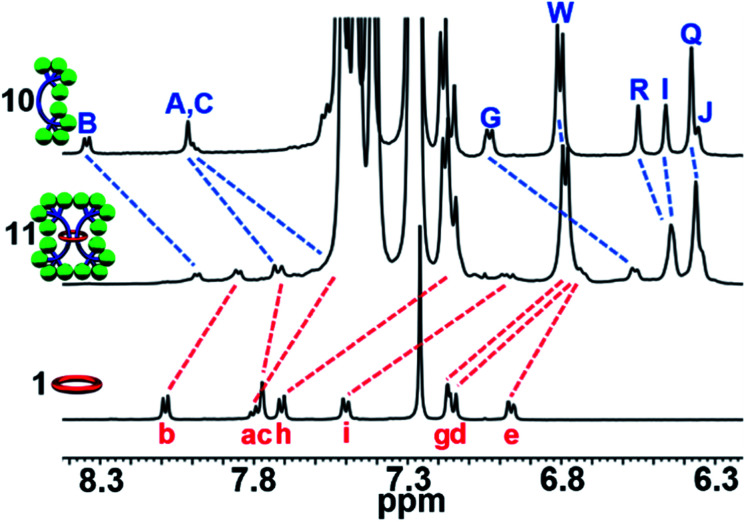

With 1, 2 and 3 in hand, and following the synthetic strategy in Fig. 1a, initial studies focused on the self-assembly of the ditopic macrocycle 1 with thread 2 to yield a doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxane via metal-templating. It is important that the doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxane self-assembles efficiently upon metal ion addition for the [3]rotaxane to be formed in high yield. Fe(ii) ions have been shown to have a high binding constant with Bip (>1010 M−2)92 and were therefore employed as the metal ion templating agent. Initially, a 2 : 1 solution of 2 and 1 in CDCl3 was prepared utilizing 1H-NMR spectroscopy to ensure a 2 : 1 stoichiometry (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Partial 1H-NMR spectra of (a) 2 : 1 mixture of 2 : 1 (500 MHz, 25 °C, CDCl3) and (b) 1 : 22 : Fe(ii)2 (500 MHz, 25 °C, 15% d3-MeCN in CDCl3) after equilibration for 1 day at 45 °C. See Fig. 1 for the corresponding proton assignments.

Upon addition of Fe(NTf2)2 to the 2 : 1 solution an instantaneous color change from colorless to dark purple was observed, indicative of the newly formed Bip-Fe(ii) complexes. Monitoring the metalation by 1H-NMR spectroscopy revealed the appearance of new signals corresponding to the metal ion complexed species and a concomitate decrease in the peak intensities that correspond to unbound 1 and 2. The metal ions were titrated into the sample until no free Bip signals were observed (ca. 2 equiv., see ESI, Fig. S2†) and the mixture was equilibrated for 1 day at 45 °C. After equilibration, the 1H-NMR spectrum simplified and, using previously published 1H NMR spectra of doubly threaded metal-templated Bip complexes,87–89 it is possible to assign each resonance peak to a given proton in the complex (Fig. 1 and 2b). The obtained doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxane is a consequence of the exact stoichiometry employed and the principle of maximal site occupancy.93 As both ligands in macrocycle 1 are not able to bind to a single metal ion (as confirmed by a UV titration experiment, see ESI, Fig. S1†), the only way for the system to maximize its enthalpic gain, and allow all Bip ligands to form a 2 : 1 Bip : Fe(ii) complex, is the formation of the pseudo[3]rotaxane. Comparison of 1 : 22 : Fe(ii)2 to a separately prepared 22 : Fe(ii) assembly confirms no metalated homo thread complexes are present (see ESI, Fig. S3†). Diffusion-ordered spectroscopy (DOSY) (in 15% d3-MeCN in CDCl3) confirmed the formation of a larger assembly with a diffusion coefficient of 1.6 × 10−10 m2 s−1 compared to 2.9 and 2.3 × 10−10 m2 s−1 for 1 and 2, respectively (see ESI, Fig. S4–7†). These results are consistent with the expected larger hydrodynamic radius of the 1 : 22 : Fe(ii)2 assembly relative to 1 and 2. Similar observations were made using macrocycle 1 with thread 3 following a similar metalation procedure to form a second doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxane 1 : 32 : Fe(ii)2 (for full details, see ESI, Fig. S8–S10 and Scheme S8†).

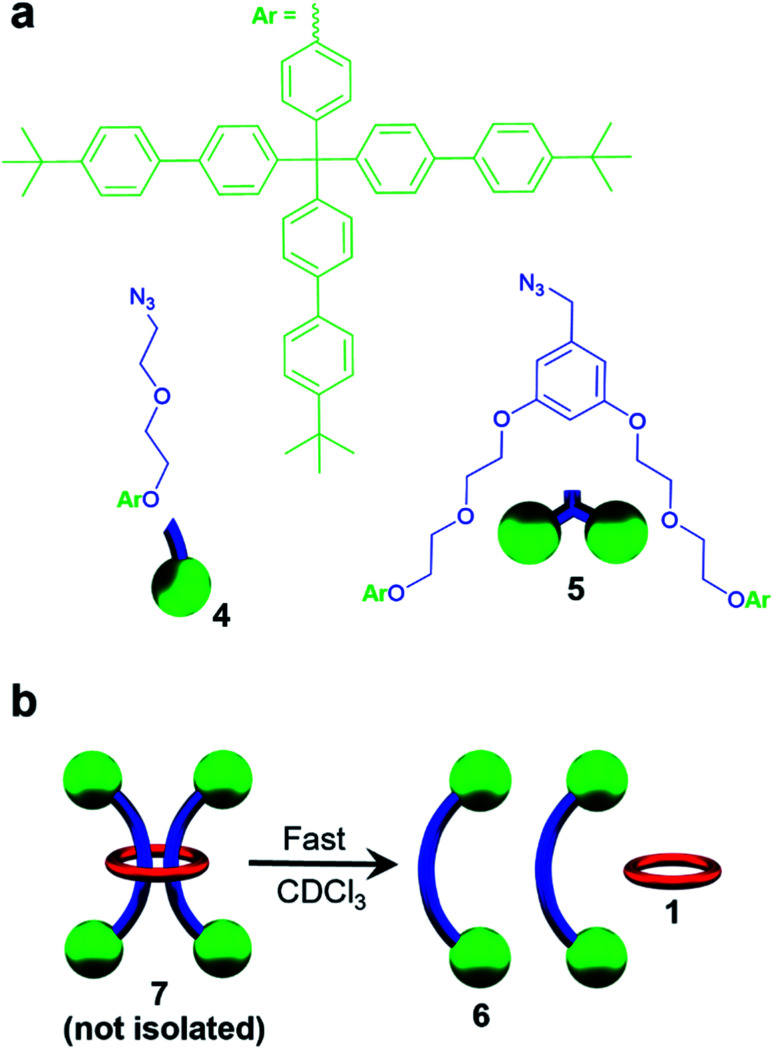

A macrocycle the size of 1 had not be used to access a [3]rotaxane before, and as such a key goal of this work was to explore different stoppering groups to see what would allow access to isolatable [3]rotaxanes with such a large ring. Initial experiments focused on using the tris(biphenyl)methyl derivative 4 as the stoppering moiety (Fig. 3a) as it is analogous in size to the largest stopper groups used in other reported doubly threaded systems.64,654 was synthesized with a terminal azide group (see ESI, Scheme S9–S12† for full synthetic details) in order to react with the alkyne-terminated thread components. In addition, a second stopper group 5 containing two tris(biphenyl)methyl moieties was also prepared (Fig. 3a), by reacting a tosyl derivative of the triaryl moieties with the phenolic OH groups in 3,5-dihydroxybenzyl alcohol and subsequently converting the benzyl alcohol to a benzyl azide (for full synthetic details see ESI, Schemes S13–S15†). To prepare the [3]rotaxanes, a modified literature procedure61,62 was employed. 1 : 22 : Fe(ii)2 was stirred in a biphasic (DCM/H2O) mixture of 4 (6 equiv.), Cu(SO4)·5H2O (1 equiv.), and sodium ascorbate (10 equiv.) overnight at room temperature (see ESI, Schemes S16 and S17† for full synthetic details including the synthesis of the free dumbbell 6). Facile demetallation of the system was achieved using tetrabutylammonium hydroxide as confirmed by a rapid color change of the solution from purple to off-white. The demetallated product was isolated and analysed immediately. Comparison of the crude demetallated 1H-NMR spectrum relative to the starting components confirmed quantitative consumption of the alkyne signal in 2, and if the 1H NMR spectrum is taken as soon as possible after demetallation (∼4 min), very small signals, upfield from the noninterlocked components, were observed (see ESI, Fig. S11†) that rapidly disappear within a couple of minutes. The presence of such upfield shifted peaks imply these protons are in a more shielded environment, and would be consistent with an interlocked structure.87–89 A MALDI-TOF MS spectrum (see ESI, Fig. S12†) of the reaction mixture recorded after 6 minutes in solution confirmed only the presence of 1 and 6, with no signals indicative of [3]rotaxane 7. Any further attempts to optimize the synthesis and isolate 7 were unsuccessful and thus, while the doubly threaded 7 may have been initially formed, these stopper groups are not large enough to prevent the rapid dethreading of the large macrocycle 1 (Fig. 3b) upon demetallation.

Fig. 3. (a) Chemical structure of stopper groups 4 and 5 used in this study. (b) Cartoon scheme depicting rapid dethreading of 7 seen.

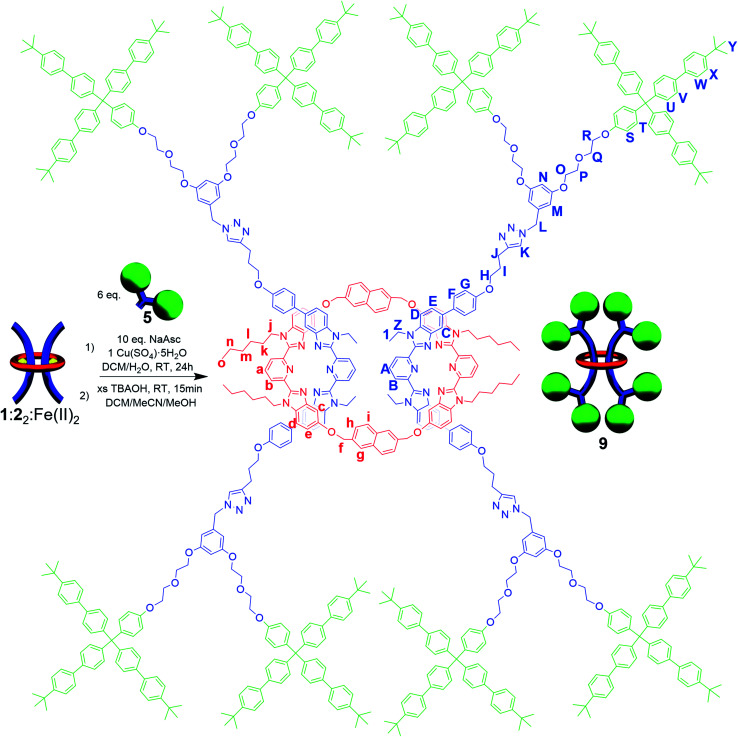

While it was not possible to isolate 7, this result is perhaps not particularly surprising on account of the large size of the ring. As such, efforts turned to exploring [3]rotaxanes featuring the same macrocycle (1) and thread (2) but with the larger stopper group 5 using the same azide/alkyne cycloaddition conditions and demetallation procedure (Fig. 4) described previously (see ESI, Schemes S18 and S19† for full synthetic details including the synthesis of the free dumbbell 8).

Fig. 4. Scheme showing synthesis and chemical structure of doubly threaded [3]rotaxane 9.

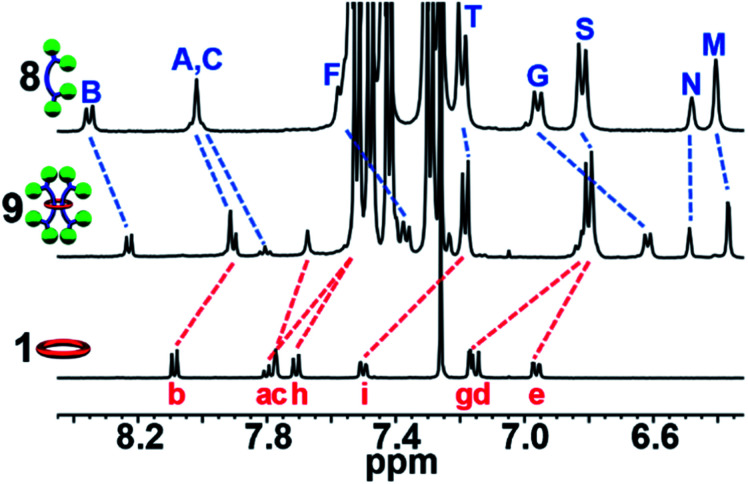

Similar to what was observed in the crude reaction mixture of the attempted synthesis of 7, the 1H-NMR analysis of the crude (demetallated) reaction mixture of the targeted synthesis of 9 revealed the presence of new signals that are shifted upfield (on average about 0.15 ppm) from the noninterlocked components. However, this time these upfield signals represent the major product with only a small amount (ca. 15%) of noninterlocked byproduct observed (see ESI, Fig. S13†). In addition, no unreacted 2 was detected. Thin layer chromatography (silica, 6% MeOH in CHCl3) confirmed a new single lower Rf product had been formed relative to the noninterlocked components. Preparative thin layer chromatography was then used to separate the lower Rf product in 75% isolated yield from its noninterlocked byproducts. Utilizing a variety of 1D and 2D NMR techniques (COSY, HSQC, HMBC, see ESI, Fig. S14–S18†) combined with comparison to the free macrocyclic and dumbbell components, 1 and 8, the 1H and 13C{1H}-NMR spectra of 9 could be fully assigned. Fig. 5 shows the diagnostic aromatic region of the 1H NMR (for full spectra see ESI, Fig. S15†).

Fig. 5. Partial aromatic 1H-NMR overlay (500 MHz, 25 °C, CDCl3) of 8 (top), 9 (middle), and 1 (bottom), 1H assignments in Fig. 4.

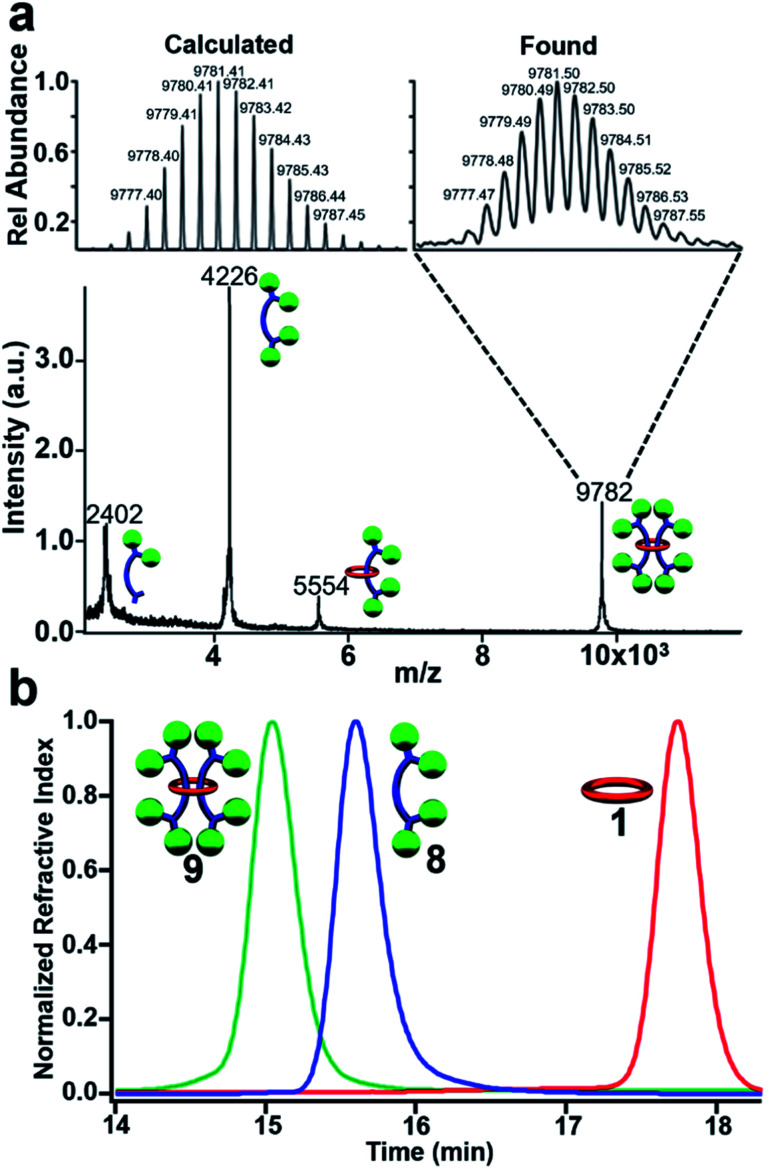

MALDI-TOF MS of purified 9 (Fig. 6a) shows a high molecular weight peak ((M + H+) m/z: 9782) that is consistent with the targeted [3]rotaxane. Additional lower molecular weight peaks ((M + H+) m/z: 5554, 4226, 2402) are also observed which are consistent with the expected fragmentation pattern of the doubly threaded interlocked structure. Breaking open the macrocycle in 9 results in free dumbbell ((M + H+) m/z: 4226) while fragmentation of a single dumbbell gives the [2]rotaxane ((M + H+) m/z: 5554) and fragmented dumbbell ((M + H+) m/z: 2402) peaks. The high molecular weight peak was further examined using reflectance mode MALDI-TOF to access the mass distribution of 9. The obtained isotopic distribution displays a clear match to the expected distribution from 9 based on its chemical composition (C676H696N32O32 (M + H+)) giving further evidence for the doubly threaded [3]rotaxane 9 (Fig. 6a expansion).

Fig. 6. (a) MALDI-TOF MS of 9 with expansion showing isotopic distribution of the 9782 m/z peak (C676H696N32O32 (MH+)). (b) GPC chromatogram of (eluent 3 : 1 THF : DMF) of purified 9, 8, and 1 at 25 °C.

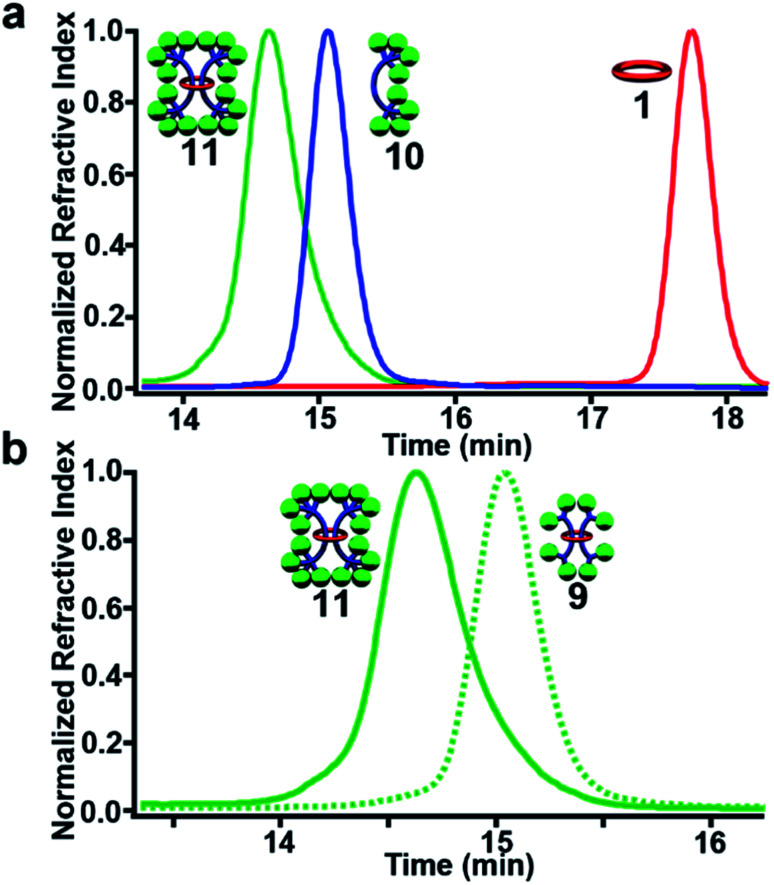

To confirm that 9 was one interlocked molecule free of its noninterlocked components, size exclusion chromatography was employed. GPC analysis using RI detection shows a single peak for 9 with a clear decrease in retention time relative to 8 and 1 (Fig. 6b) as would be expected for the larger doubly threaded architecture. In addition, DOSY NMR was utilized to determine their hydrodynamic radii, which were found to be 1.89, 0.97, and 0.71 nm, for 9, 8 and 1 respectively (see ESI, Fig. S19–S22†). This roughly doubling in size between 9 and 8 is consistent with the doubly threaded structure.

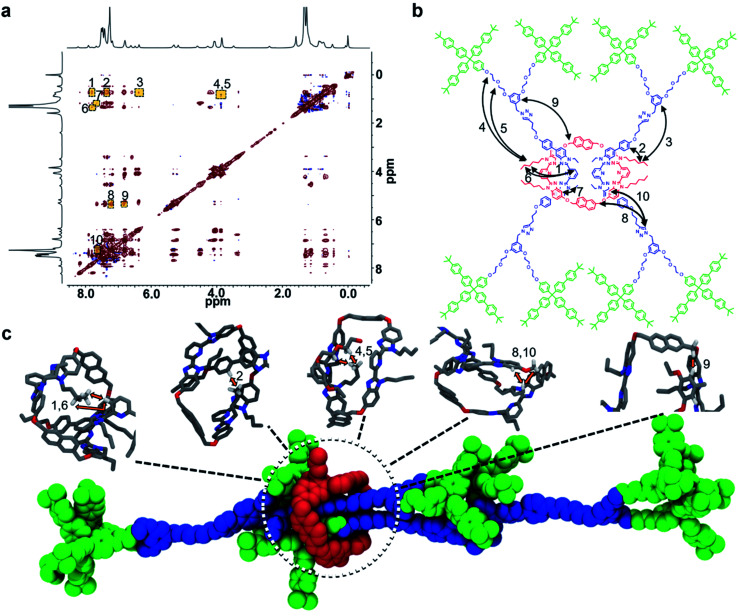

The close proximity of the interlocked components in 9 was demonstrated using 1H–1H NOESY NMR experiments carried out at 278 K. At this temperature, 10 different intercomponent NOEs could be identified in 9 (Fig. 7a and b) that were not present in a separately prepared 2 : 1 mixture of the dumbbell 8 and macrocycle 1 at the same concentration (see ESI, Fig. S23–S24†).

Fig. 7. (a) Full 1H–1H NOESY NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) of 9 at 278 K. (b) Schematic diagram showing labeled intercomponent NOEs of 9. (c) All-atom implicit-solvent model renders of 9 showing how NOEs 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10 could arise. In the upper panel, molecular segments are colored according to atom type (gray = carbon, blue = nitrogen, red = oxygen, white = hydrogen). In the bottom panel, the various rotaxane components are colored in accordance with the rest of the figures (red = ring, blue = thread, green = stopper(s)).

NOEs typically arise from distances <5.0 Å (ref. 94) and as such the presence of 10 different intercomponent NOEs confirms that the components of 9 are indeed interlocked. It is interesting to note that there are NOE interactions between 1 and the entire length of the dumbbell component within 9 suggesting that there is some free mobility of the ring along the dumbbell. To better understand how these NOE interactions might occur, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations were conducted to help explore possible rotaxane conformations that could explain the observed NOE signals (Fig. 7c, see ESI and Fig. S25–S29† for full details). The simulations show that the macrocycle typically assumes a position near a stopper group of one dumbbell and in the middle of the other (as shown in Fig. 7c). It is worth pointing out that such conformations are consistent with the majority of the NOEs observed (1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10).

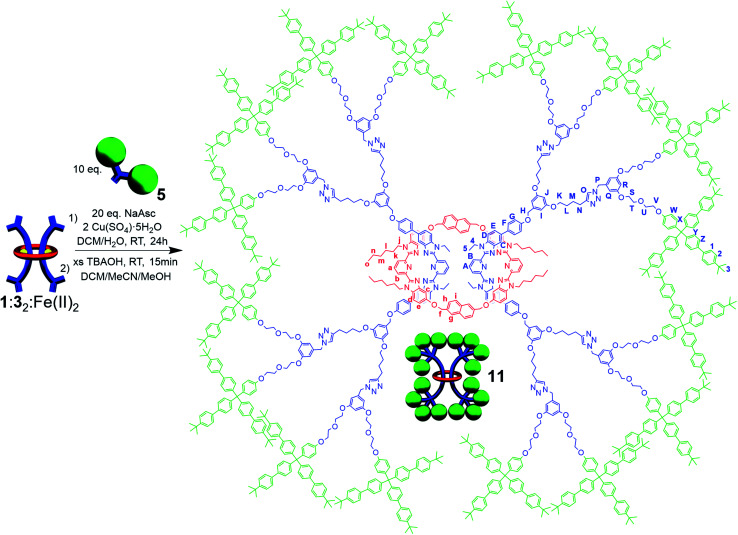

During the NMR analysis of 9, an interesting observation was made. Specifically, after being in solution overnight during 13C{1H}-NMR acquisition, small trace signals were observed in the 1H-NMR spectrum that correspond to free dumbbell and macrocycle. As a consequence of this observation and the large size of 1, it was hypothesized that even with the larger stopper group 5, very slow slippage may be occurring in solution and that the [3]rotaxane 9 is in fact metastable. As such, the doubly threaded [3]rotaxane 11 (Fig. 8), which effectively doubles the size of the stopper group used in 9, was targeted. In order to access such a structure, the doubly threaded pseudo[3]rotaxane 1 : 32 : Fe(ii)2 (which contains the thread component 3 with two alkyne moieties on each end group), was stoppered with 5 and demetallated using similar conditions to those used to synthesize 9 (see ESI, Schemes S20 and S21† for full synthetic details including the synthesis of the free dumbbell 10).

Fig. 8. Scheme showing synthesis and chemical structure of doubly threaded [3]rotaxane 11.

1H-NMR analysis of the crude product again revealed new upfield shifted signals from the noninterlocked components with a small amount (ca. 25%) of noninterlocked byproduct observed (macrocycle 1 and dumbbell 10, see ESI, Fig. S30†) and thin layer chromatography (silica, 5% MeOH in CHCl3) confirmed a new single lower Rf product had been formed relative to the noninterlocked components. Preparative thin layer chromatography was used to isolate this new product in 65% yield. The entire 1H NMR spectrum of 11 could be assigned (see ESI, Fig. S31 and S32†) by comparison to the spectra of 1, 9, and 10 combined with 1H–1H COSY of 11 (see ESI, Fig. S33†). Fig. 9 shows the diagnostic aromatic region which reveals an average upfield shift of 0.3 ppm was observed for the aromatic resonances of 11 compared to its noninterlocked components 1 and 10. It is interesting to note this upfield shift is significantly larger than what was observed for the [3]rotaxane 9.

Fig. 9. Partial aromatic 1H-NMR (500 MHz, 25 °C, CDCl3) overlay of 10 (top), 11 (middle), and 1 (bottom), 1H assignments in Scheme S2†.

GPC analysis using RI detection shows a clear decrease in retention time of 11 relative to its noninterlocked components 10 and 1 (Fig. 10a) and the [3]rotaxane 9 (Fig. 10b) as expected. Finally, MALDI-TOF MS of purified 11 shows the expected fragmentation pattern of the interlocked structure (see ESI, Fig. S34†).

Fig. 10. GPC chromatogram of (3 : 1 THF : DMF as eluent) purified 11, 10, and 1 (a) and 11 and 9 (b) at 298 K.

Slippage kinetics of [3]rotaxanes 9 and 11

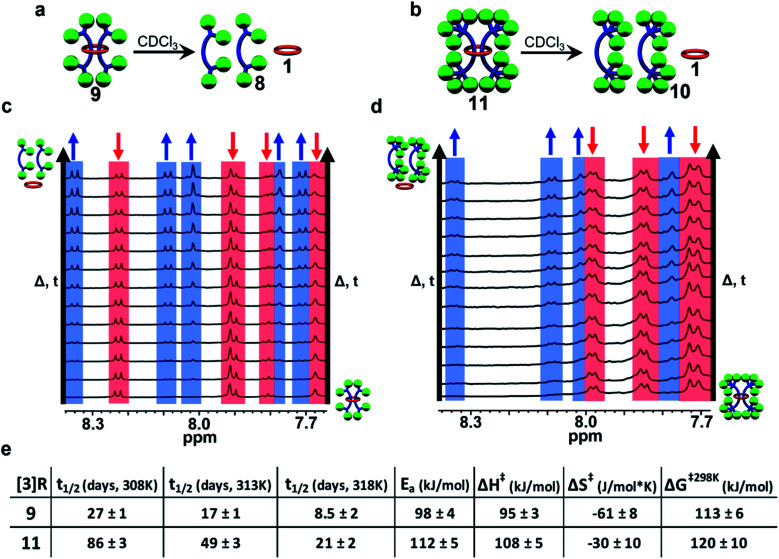

While the [3]rotaxane 7 was not stable enough to be isolated, both [3]rotaxanes 9 and 11 were isolatable and stable enough to withstand chromatography conditions. None-the-less, as mentioned above the [3]rotaxane 9 appeared to be metastable. Thus, it was decided to explore the lifetime solution stability of both [3]rotaxanes 9 and 11 in more detail. To this end freshly purified solutions of 9 and 11 were monitored via1H NMR spectroscopy at room temperature (25 °C, CDCl3, 1 mM [3]rotaxane) for six weeks. Interestingly in both cases, the upfield shifted protons assigned to the rotaxane slowly decreased in intensity and were replaced with new signals identical to those of the corresponding free dumbbell and macrocycle (see ESI, Fig. S35†) indicative of both compounds undergoing a slow slippage process (Fig. 11a and b). These initial experiments suggested that at 25 °C 9 had a half-life (t1/2) of ca. 5 weeks while 11 exhibited a t1/2 on the order of ca. 6 months.

Fig. 11. Scheme illustrating the slippage process of (a) 9 and (b) 11. Partial 1H-NMR overlay (500 MHz, CDCl3) of a 3 week slippage experiment of (c) 9 and (d) 11. (e) Table summarizing the kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of the slippage processes of 9 and 11 in CDCl3.

In order to obtain more detailed information on the stability of these metastable double threaded [3]rotaxanes, a full kinetic study was carried out on freshly purified solutions of 9 and 11 in CDCl3 (1 mM [3]rotaxane).62 Both solutions were monitored at 35 °C for one week followed by 40 °C for another week, and finally 45 °C for a final week with their 1H-NMR spectra recorded at regular time intervals (Fig. 11c and d). This process was repeated in triplicate for both rotaxanes and the concentration of remaining [3]rotaxane in solution could easily be determined from integration of the 1H-NMR spectra at each timepoint (see ESI and Fig. S36–S40† for full details). Standard kinetic analysis revealed the slippage process followed first-order kinetics dependent on the concentration of the [3]rotaxane (i.e., rate of slippage = k1[rotaxane]) with the indicated half-lives at different temperatures show in Fig. 9e (see ESI, Fig. S41 and S42†). In addition to NMR spectroscopy, GPC was used to confirm that the only new products obtained after the 3 week slippage experiments of 9 and 11 were the corresponding free dumbbell and macrocycle (see ESI, Fig. S43 and S44†). One important observation from both of these studies is that no singly threaded [2]rotaxane intermediate was observed during any of the slippage trials conducted which suggests that any of the corresponding singly threaded [2]rotaxanes using 1 are not stable on any appreciable timescale. This makes sense as it can be expected that the presence of one dumbbell “trapped” within the macrocycle helps to hinder slippage of the second dumbbell.

Standard Arrhenius and Eyring analysis provided the thermodynamic parameters to both slippage processes (Fig. 11e, see ESI, Fig. S45–S48†). Direct comparison to other rotaxane systems in literature is difficult as such data is not typically reported. However, it is worthwhile noting that the activation energy of the slippage process in both 9 (98 ± 4 kJ mol−1) and 11 (112 ± 5 kJ mol−1) are very high compared to the only other doubly threaded [3]rotaxane for which such data is available (35 ± 3 kJ mol−1)62 and is consistent with the very slow slippage process observed in these systems. Comparing 11 to 9 shows that while effectively doubling the number of the tris(p-t-butylbiphenyl)methyl moieties on the stopper group does not prevent slippage, it does result in an increase in the energy barrier to dethreading and a dramatic increase in the lifetime stability of the [3]rotaxane (t1/2 of 5 weeks vs. 6 months at room temperature).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the successful assembly, stoppering, and demetallation of Bip-containing doubly threaded [3]rotaxanes using one of the largest macrocycles reported to date (46 atoms) has been achieved in good yield. On account of the large size of the macrocycle in these interlocked species, all of the [3]rotaxanes synthesized were found to be metastable and that by tuning the number of tris(p-t-butylbiphenyl)methyl moieties present in the stoppering unit it was possible to vary their stability with their half-life varying from <1 minute (one tris(p-t-butylbiphenyl)methyl moiety) to ca. 6 months (four tris(p-t-butylbiphenyl)methyl moieties) at room temperature. In fact, two of these metastable [3]rotaxanes were stable enough to withstand column chromatography and allow a full suite of characterization experiments, 1H–1H-NOESY, DOSY, GPC, and MALDI-MS, to confirm their assigned interlocked structure. The extremely slow slippage of [3]rotaxanes 9 and 11 is especially intriguing as it opens the door to the development of a range of relatively long lived metastable materials. For example, the utilization of such metastable doubly threaded rotaxanes may allow access to polyrotaxane networks/slide ring gels whose degradation rate can be controlled or are able to be reprocessed. Work along these lines is currently underway.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and ESI,† and raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributions

JEH, LFH, and SJR proposed the study. KMH and EPB conducted initial experiments. JEH conducted the synthesis, characterization, and analysis of all materials described with assistance from VJM, LFH, and BWR. Molecular simulations were conducted by VJM, PMR, and JJP. SJR supervised the work. JEH, BWR, and SJR wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Science Foundation (NSF) grant numbers CHE-1700847 and CHE-1903603. This work made use of the shared facilities at the University of Chicago Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (MRSEC), supported by National Science Foundation (NSF) under award number DMR-2011854. We would like to thank the University of Chicago Chemistry NMR Facility and the facility manager Dr Josh Kurutz for helpful discussion on NMR analysis. Parts of this work were carried out at the Soft Matter Characterization Facility (SMCF) of the University of Chicago. We would also like to thank the director of the SMCF, Dr Phillip Griffin, for his assistance with GPC characterization. Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted with resources awarded by the Research Computing Center at the University of Chicago.

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc01486f

References

- Stoddart J. F. The chemistry of the mechanical bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1802–1820. doi: 10.1039/B819333A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns C. J. and Stoddart J. F., The Nature of the Mechanical Bond: From Molecules to Machines, Wiley, 2016, 10.1002/9781119044123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvage J.-P. From Chemical Topology to Molecular Machines (Nobel Lecture) Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:11080–11093. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feringa B. L. The Art of Building Small: From Molecular Switches to Motors (Nobel Lecture) Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:11060–11078. doi: 10.1002/anie.201702979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart J. F. Mechanically Interlocked Molecules (MIMs)-Molecular Shuttles, Switches, and Machines (Nobel Lecture) Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017;56:11094–11125. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal P. R. Multiply threaded rotaxanes. Supramol. Chem. 2018;30:782–794. doi: 10.1080/10610278.2018.1433832. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xue M. Yang Y. Chi X. Yan X. Huang F. Development of Pseudorotaxanes and Rotaxanes: From Synthesis to Stimuli-Responsive Motions to Applications. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:7398–7501. doi: 10.1021/cr5005869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbas-Cakmak S. Leigh D. A. McTernan C. T. Nussbaumer A. L. Artificial Molecular Machines. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:10081–10206. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Y. Han Y. Chen C. F. PH-controlled motions in mechanically interlocked molecules. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020;4:12–28. doi: 10.1039/C9QM00546C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dattler D. et al., Design of Collective Motions from Synthetic Molecular Switches, Rotors, and Motors. Chem. Rev. 2020;120:310–433. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A. et al., Making hybrid [n]-rotaxanes as supramolecular arrays of molecular electron spin qubits. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath J. R. Wires, switches, and wiring. A route toward a chemically assembled electronic nanocomputer. Pure Appl. Chem. 2000;72:11–20. doi: 10.1351/pac200072010011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson E. M. G. Modicom F. Goldup S. M. Chirality in rotaxanes and catenanes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:5266–5311. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00097B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. E. M. Galli M. Goldup S. M. Properties and emerging applications of mechanically interlocked ligands. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:298–312. doi: 10.1039/C6CC07377H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotí K. K. et al., Mechanised nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nanoscale. 2009;1:16–39. doi: 10.1039/B9NR00162J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison I. T. Harrison S. Synthesis of a stable complex of a macrocycle and a threaded chain. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1967;89:5723–5724. doi: 10.1021/ja00998a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taghavi Shahraki B. et al., The flowering of mechanically interlocked molecules: novel approaches to the synthesis of rotaxanes and catenanes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020;423:213484. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213484. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. Y. Zong Q. S. Han Y. Chen C. F. Recent advances in higher order rotaxane architectures. Chem. Commun. 2020;56:9916–9936. doi: 10.1039/D0CC03057K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart L. F. et al., Material properties and applications of mechanically interlocked polymers. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2021;6:508–530. doi: 10.1038/s41578-021-00278-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mena-Hernando S. Pérez E. M. Mechanically interlocked materials. Rotaxanes and catenanes beyond the small molecule. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:5016–5032. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00888D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacljić J. D. Balzani V. Credi A. Silvi S. Stoddart J. F. A Molecular Elevator. Science. 2004;303:1845–1849. doi: 10.1126/science.1094791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada Y. Okamoto M. Furukawa K. Kato T. Tanaka K. Switchable intermolecular communication in a four-fold rotaxane. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:709–713. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang L. et al., Acid-base actuation of [c2]daisy chains. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:7126–7134. doi: 10.1021/ja900859d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G. Moulin E. Jouault N. Buhler E. Giuseppone N. Muscle-like supramolecular polymers: integrated motion from thousands of molecular machines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012;51:12504–12508. doi: 10.1002/anie.201206571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Z. Chen C. F. A molecular pulley based on a triply interlocked [2]rotaxane. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:8241–8244. doi: 10.1039/C5CC01301A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okumura Y. Ito K. The polyrotaxane gel: a topological gel by figure-of-eight cross-links. Adv. Mater. 2001;13:485–487. doi: 10.1002/1521-4095(200104)13:7<485::AID-ADMA485>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K. Novel cross-linking concept of polymer network: synthesis, structure, and properties of slide-ring gels with freely movable junctions. Polym. J. 2007;39:489–499. doi: 10.1295/polymj.PJ2006239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noda Y. Hayashi Y. Ito K. From topological gels to slide-ring materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014;131:40509. doi: 10.1002/app.40509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rauscher P. M. Schweizer K. S. Rowan S. J. de Pablo J. J. Dynamics of poly[n]catenane melts. J. Chem. Phys. 2020;152:214901. doi: 10.1063/5.0007573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagita K. Murashima T. Sakata N. Mathematical Classification and Rheological Properties of Ring Catenane Structures. Macromolecules. 2021;55:166–177. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.1c01705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda Y. et al., Sliding Dynamics of Ring on Polymer in Rotaxane: A Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics Simulation Study. Macromolecules. 2019;52:3787–3793. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.9b00118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oddy F. E. et al., Influence of cyclodextrin size on fluorescence quenching in conjugated polyrotaxanes by methyl viologen in aqueous solution. J. Mater. Chem. 2009;19:2846–2852. doi: 10.1039/B821950H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K. Karube K. Nakamura N. Ito K. The effect of ring size on the mechanical relaxation dynamics of polyrotaxane gels. Polym. Chem. 2015;6:2241–2248. doi: 10.1039/C4PY01644K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S. Nakazono K. Takahashi E. April R. V. Template Synthesis of [2] Rotaxanes with Large Ring Components and Tris(biphenyl) methyl Group as the Blocking Group. The Relationship between the Ring Size and the Stability of the Rotaxanes. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:7477–7480. doi: 10.1021/jo060829h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S. et al., Synthesis of Large [2]Rotaxanes, The Relationship between the Size of the Blocking Group and the Stability of the Rotaxane. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:3553–3560. doi: 10.1021/jo302800t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymo F. M. Houk K. N. Stoddart J. F. The mechanism of the slippage approach to rotaxanes. Origin of the ‘all- or-nothing’ substituent effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9318–9322. doi: 10.1021/ja9806229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Affeld A. Hühner G. M. Seel C. Schalley C. A. Rotaxane or pseudorotaxane? Effects of small structural variations on the deslipping kinetics of rotaxanes with stopper groups of intermediate size. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:2877–2890. doi: 10.1002/1099-0690(200108)2001:15<2877::AID-EJOC2877>3.0.CO;2-R. doi: 10.1002/1099-0690(200108)2001:15<2877::AID-EJOC2877>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Linnartz P. Bitter S. Schalley C. A. Deslipping of Ester Rotaxanes: A Cooperative Interplay of Hydrogen Bonding with Rotational Barriers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003:4819–4829. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300466. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heim C. Affeld A. Nieger M. Vögtle F. Size complementarity of macrocyclic cavities and stoppers in amide- rotaxanes. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1999;82:746–759. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2675(19990505)82:5<746::AID-HLCA746>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groppi J. et al., Precision Molecular Threading/Dethreading. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:14825–14834. doi: 10.1002/anie.202003064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Händel M. Plevoets M. Gestermann S. Vögtle F. Synthesis of Rotaxanes by Brief Melting of Wheel and Axle Components. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1997;36:1199–1201. doi: 10.1002/anie.199711991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton P. R. et al., Rotaxane or pseudorotaxane? That is the question! J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:2297–2307. doi: 10.1021/ja9731276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu S. et al., A Rotaxane-Like Complex with Controlled-Release Characteristics. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3631–3634. doi: 10.1021/ol006525d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherraben S. Scelle J. Hasenknopf B. Vives G. Sollogoub M. Precise Rate Control of Pseudorotaxane Dethreading by pH-Responsive Selectively Functionalized Cyclodextrins. Org. Lett. 2021;23:7938–7942. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c02940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling X. Samuel E. L. Patchell D. L. Masson E. Cucurbituril slippage: Translation is a complex motion. Org. Lett. 2010;12:2730–2733. doi: 10.1021/ol1008119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. et al., A precise polyrotaxane synthesizer. Science. 2020;368:1247–1253. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y. et al., A Molecular Dual Pump. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:17472–17476. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b08927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. et al., An artificial molecular pump. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015;10:547–553. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzato C. et al., An efficient artificial molecular pump. Tetrahedron. 2017;73:4849–4857. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2017.05.087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M. A. Lelj F. MacLachlan M. J. Programming permanent and transient molecular protection: via mechanical stoppering. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:10422–10427. doi: 10.1039/C9SC03744F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto M. A. Maclachlan M. J. Disabling Molecular Recognition through Reversible Mechanical Stoppering. Org. Lett. 2019;21:1744–1748. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh S. Y. et al., Protecting a squaraine near-IR dye through its incorporation in a slippage-derived [2]rotaxane. Org. Lett. 2007;9:4523–4526. doi: 10.1021/ol702050w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang T. H. et al., Using Slippage to Construct a Prototypical Molecular ‘lock & Lock’ Box. Org. Lett. 2021;23:5787–5792. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.1c01945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J. White A. G. Baumes J. M. Smith B. D. Microwave-assisted slipping synthesis of fluorescent squaraine rotaxane probe for bacterial imaging. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:1068–1069. doi: 10.1039/B924350J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan M. M. Yu Z. J. Luo H. Y. Zhang S. Li B. J. Supramolecular network based on the self-assembly of y-cyclodextrin with poly(ethylene glycol) and its shape memory effect. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009;30:897–903. doi: 10.1002/marc.200800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iijima K. Aoki D. Otsuka H. Takata T. Synthesis of rotaxane cross-linked polymers with supramolecular cross-linkers based on γ-CD and PTHF macromonomers: the effect of the macromonomer structure on the polymer properties. Polymer. 2017;128:392–396. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2017.01.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K. Nameki R. Sogawa H. Takata T. Macrocyclic Dinuclear Palladium Complex as a Novel Doubly Threaded [3]Rotaxane Scaffold and Its Application as a Rotaxane Cross-Linker. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020;59:18023–18028. doi: 10.1002/anie.202007866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aramoto H. et al., Redox-responsive supramolecular polymeric networks having double-threaded inclusion complexes. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:4322–4331. doi: 10.1039/C9SC05589D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danon J. J. Leigh D. A. McGonigal P. R. Ward J. W. Wu J. Triply Threaded [4]Rotaxanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:12643–12647. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz E. J. F. Claridge T. D. W. Anderson H. L. Homo- and hetero-[3]rotaxanes with two π-systems clasped in a single macrocycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15374–15375. doi: 10.1021/ja0665139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prikhod’ko A. I. Durola F. Sauvage J. P. Iron(ii)-templated synthesis of [3]rotaxanes by passing two threads through the same ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:448–449. doi: 10.1021/ja078216p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prikhod’ko A. I. Sauvage J. P. Passing two strings through the same ring using an octahedral metal center as template: a new synthesis of [3]rotaxanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6794–6807. doi: 10.1021/ja809267z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H. M. et al., En route to a molecular sheaf: active metal template synthesis of a [3]rotaxane with two axles threaded through one ring. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12298–12303. doi: 10.1021/ja205167e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita Y. Mutoh Y. Yamasaki R. Kasama T. Saito S. Synthesis of [3]rotaxanes that utilize the catalytic activity of a macrocyclic phenanthroline-Cu complex: remarkable effect of the length of the axle precursor. Chem.–Eur. J. 2015;21:2139–2145. doi: 10.1002/chem.201405090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi R. Mutoh Y. Kasama T. Saito S. Synthesis of [3]Rotaxanes by the Combination of Copper-Mediated Coupling Reaction and Metal-Template Approach. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:7536–7546. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movsisyan L. D. et al., Polyyne Rotaxanes: Stabilization by Encapsulation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1366–1376. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa M. et al., The slipping approach to self-assembling [n]rotaxanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:302–310. doi: 10.1021/ja961817o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans N. H. Recent Advances in the Synthesis and Application of Hydrogen Bond Templated Rotaxanes and Catenanes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2019:3320–3343. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201900081. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201900081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nepogodiev S. A. Stoddart J. F. Cyclodextrin-based catenanes and rotaxanes. Chem. Rev. 1998;98:1959–1976. doi: 10.1021/cr970049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisner J. A. Beer P. D. Drew M. G. B. Sambrook M. R. Anion-templated rotaxane formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12469–12476. doi: 10.1021/ja027519a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beves J. E. Blight B. A. Campbell C. J. Leigh D. A. McBurney R. T. Strategies and tactics for the metal-directed synthesis of rotaxanes, knots, catenanes, and higher order links. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:9260–9327. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. E. M. Beer P. D. Loeb S. J. Goldup S. M. Metal ions in the synthesis of interlocked molecules and materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017;46:2577–2591. doi: 10.1039/C7CS00199A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inthasot A. Tung S. Te. Chiu S. H. Using Alkali Metal Ions to Template the Synthesis of Interlocked Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2018;51:1324–1337. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambron J. C. et al., Rotaxanes and catenanes built around octahedral transition metals. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2004:1627–1638. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300341. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.200300341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Collin J. P. Dietrich-Buchecker C. Gaviña P. Jimenez-Molero M. C. Sauvage J. P. Shuttles and muscles: linear molecular machines based on transition metals. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:477–487. doi: 10.1021/ar0001766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambron J. C. Heitz V. Sauvage J. P. A rotaxane with two rigidly held porphyrins as stoppers. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1992:1131–1133. doi: 10.1039/C39920001131. doi: 10.1039/C39920001131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley J. D. Goldup S. M. Lee A. L. Leigh D. A. Mc Burney R. T. Active metal template synthesis of rotaxanes, catenanes and molecular shuttles. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:1530–1541. doi: 10.1039/B804243H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis M. Goldup S. M. The active template approach to interlocked molecules. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017;1:1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41570-016-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley J. D. Hänni K. D. Lee A. L. Leigh D. A. [2]Rotaxanes through palladium active-template oxidative heck cross-couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12092–12093. doi: 10.1021/ja075219t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie B. M. et al., Improved synthesis of functionalized mesogenic 2,6-bisbenzimidazolylpyridine ligands. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:8488–8495. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.05.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnworth M. et al., Optically healable supramolecular polymers. Nature. 2011;472:334–337. doi: 10.1038/nature09963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck J. B. Ineman J. M. Rowan S. J. Metal/Ligand-Induced Formation of Metallo-Supramolecular Polymers. Macromolecules. 2005;38:5060–5068. doi: 10.1021/ma050369e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehara M. Kodzuk E. Teranishi T. Self-assembly of small gold nanoparticles through interligand interaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:13084–13094. doi: 10.1021/ja064510q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S. C. Hou S. Chan W. K. Synthesis, metal complex formation, and electronic properties of a novel conjugate polymer with a tridentate 2,6-bis(benzimidazol-2-yl)pyridine ligand. Macromolecules. 1999;32:5251–5256. doi: 10.1021/ma990056h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michal B. T. McKenzie B. M. Felder S. E. Rowan S. J. Metallo-, thermo-, and photoresponsive shape memory and actuating liquid crystalline elastomers. Macromolecules. 2015;48:3239–3246. doi: 10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet C. Bernardinelli G. Williams A. F. Bocquet B. Formation of the First Isomeric [2]Catenates by Self-Assembly about Two Different Metal Ions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1995;34:582–584. doi: 10.1002/anie.199505821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtecki R. J. et al., Optimizing the formation of 2,6-bis(N-alkyl-benzimidazolyl)pyridine-containing [3]catenates through component design. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:4440–4448. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52082J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. et al., Poly[n]catenanes: Synthesis of molecular interlocked chains. Science. 2017;358:1434–1439. doi: 10.1126/science.aap7675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tranquilli M. M. Wu Q. Rowan S. J. Effect of metallosupramolecular polymer concentration on the synthesis of poly[n]catenanes. Chem. Sci. 2021;12:8722–8730. doi: 10.1039/D1SC02450G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldal M. Tomøe C. W. Cu-catalyzed azide – alkyne cycloaddition. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2952–3015. doi: 10.1021/cr0783479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hänni K. D. Leigh D. A. The application of CuAAC ‘click’ chemistry to catenane and rotaxane synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;39:1240–1251. doi: 10.1039/B901974J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enamullah M. Linert W. Substituent- and solvent-effects on the stability of iron(ii)-4-x-2,6-bis-(benzimidazol-2′-YL)pyridine complexes showing spin-crossover in solution. J. Coord. Chem. 1996;40:193–201. doi: 10.1080/00958979608024344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R. Lehn J. Bel I. Le. Pasteur U. L. Marquis-rigault A. Self-recognition in helicate self-assembly: spontaneous formation of helical metal complexes from mixtures of ligands and metal ions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:5394–5398. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T. Güntert P. Wüthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE-identification in the NOESY spectra using the new software ATNOS. J. Biomol. NMR. 2002;24:171–189. doi: 10.1023/A:1021614115432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and ESI,† and raw data files are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.