Abstract

Background

Development of vaccines with high efficacy against COVID-19 disease has ushered a new ray of hope in the fight against the pandemic. Thromboembolic events have been reported after administration of vaccines. We aim to systematically review thromboembolic events reported after COVID-19 vaccination.

Methods

The available literature was systematically screened for available data on thromboembolic events after COVID-19 vaccination. Data were extracted from selected studies and analyzed for site of thromboembolism as well as other risk factors. All data were pooled to determine cumulative incidence of thromboembolism at various sites after vaccination.

Results

A total of 20 studies were selected for the final analysis. The mean age of the population was 48.5 ± 15.4 years (females - 67.4%). The mean time to event after vaccination was 10.8 ± 7.2 days. Venous thrombosis (74.8%, n = 214/286) was more common than arterial thrombosis (27.9%, n = 80/286). Cerebral sinus thrombosis was the most common manifestation (28.3%, n = 81/286) of venous thrombosis followed by deep vein thrombosis (19.2%, n = 49/254). Myocardial infarction was common (20.1%, n = 55/274) in patients with arterial thrombosis followed by ischemic stroke (8.02%, n = 22/274). Concurrent thrombosis at multiple sites was noted in 15.4% patients. Majority of patients had thrombocytopenia (49%) and antiplatelet factor 4 antibodies (78.6%). Thromboembolic events were mostly reported after the AstraZeneca vaccine (93.7%). Cerebral sinus thrombosis was the most common among thromboembolic events reported after the AstraZeneca vaccine. Among the reported cases, mortality was noted in 29.9% patients.

Conclusions

Thromboembolic events can occur after COVID-19 vaccination, most commonly after the AstraZeneca vaccine. Cerebral sinus thrombosis is the most common manifestation noted in vaccinated individuals.

Introduction

The ongoing COVID-19 disease is a multisystem disorder which mainly affects the lungs, with the potential of causing permanent damage in the organs involved.1 Pulmonary involvement ranges from mild pneumonia to acute respiratory distress syndrome and respiratory failure. Cardiac involvement is also common with a wide variety of manifestations, ranging from acute coronary syndrome to heart failure.2 COVID-19 disease produces a proinflammatory and prothrombotic environment which can precipitate both arterial and venous thrombosis. Pulmonary thromboembolism is one of the most common types of thrombosis encountered in COVID-19 infection.3

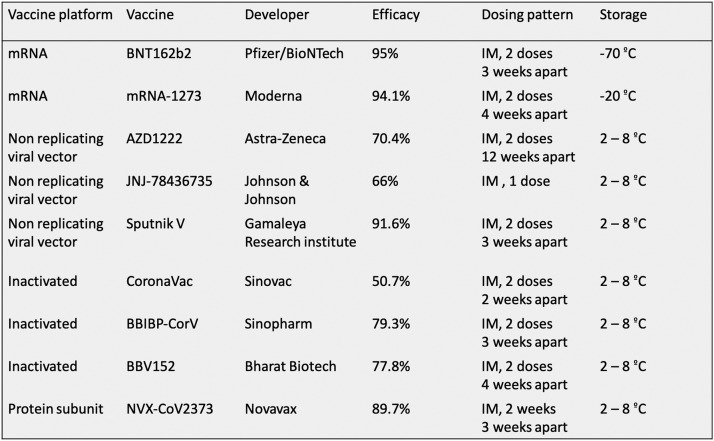

A number of vaccines have been developed by scientists worldwide, in record time, to provide immunity against severe COVID-19 disease. Different vaccines with varied technologies are available presently for use (Fig. 1 ). Each vaccine has a different mechanism of inducing immunity depending on their components. Majority of adverse events reported after vaccine administration have been minor, ranging from injection site pain to fever. A systematic review of adverse events reported after COVID-19 vaccination revealed that majority of patients had minor side effects like injection site pain, redness, and swelling.4 With time, various reports of patients developing thromboembolic events after receiving COVID-19 vaccination have been published. This was commonly seen with the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 n Cov-19 vaccine. Concerns were raised regarding the risks associated with vaccine administration. Upon the analysis of available data, the reported rates of venous and arterial thromboembolism were 0.075 and 0.13 cases per 1 million people on vaccinated days, which was lower than the average thromboembolism risk in the general population.5 Although the reports of thromboembolic events after COVID-19 vaccination are scattered in literature, there is no up-to-date comprehensive compilation of the data available in the literature. This systematic review, the first on this topic, was performed to collate the available information regarding all the thrombotic events reported after COVID-19 vaccination, available in the literature till date.

Fig. 1.

Different types of vaccines currently approved for use against COVID-19 disease.

Methods

Search Strategy

The search strategy was developed according to the guidelines laid down by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. The study was registered with Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. We performed an extensive electronic search of 4 databases: PubMed, Embase, Google Scholar, and World Health Organization library, using these keywords: “Covid-19,” “Covid,” “coronavirus,” “2019-nCoV,” “nCoV-2,” “SARS-Cov-2,” “vaccination,” “vaccine,” “thromboembolism,” “thrombosis,” and “embolism” using the Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” on June 06, 2021. The reference lists of the initially selected studies were screened for additional sources. All duplicate studies in the search were removed.

Study Selection

The inclusion criteria for research selected in this review were all reports of thromboembolic events reported after COVID-19 vaccination in the general population. Additional criteria were that the research was published in English and the entire patient data were fully extractable. Pictorial reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis were not included in the study. The selected studies were independently reviewed by 2 authors (AM and VO) based on the abovementioned inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by consensus and, if required, in consultation with a third reviewer. The quality of the selected studies was assessed on the basis of the National Institutes of Health quality assessment tool for case series studies by 2 independent reviewers.6

Data Extraction

The complete data from the selected studies were extracted and reviewed again as per the eligibility criteria. Subsequently, the final list of studies was arrived at. The data from the selected studies were extracted by 2 independent reviewers into a Microsoft Excel datasheet. As we only extracted data on reported thromboembolic events after COVID-19 vaccination, the exact prevalence of thromboembolic events in the general population cannot be determined from our study. Data extracted were grouped under multiple headings like year and country of publication, demographics, type of the COVID-19 vaccine administered, days after vaccination, and number of thrombotic events noted. Various subfields were used to classify the thrombosis data and relevant laboratory investigations in the form of site of thrombosis (arterial/venous), thrombosis at multiple sites, predisposing factors for thrombosis, presence of antiplatelet factor (PF) 4 antibodies, and D-dimer and fibrinogen levels. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the data was done using SPSS, version 25 (IBM, Armonk, NY). The data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Continuous data with a normal distribution were presented as mean ± standard deviation, whereas nonparametric data were presented as median (interquartile range). Categorical data were presented as proportions. Due to heterogeneity of the data, we primarily aimed to perform a narrative synthesis of findings (synthesis without meta-analysis).

Results

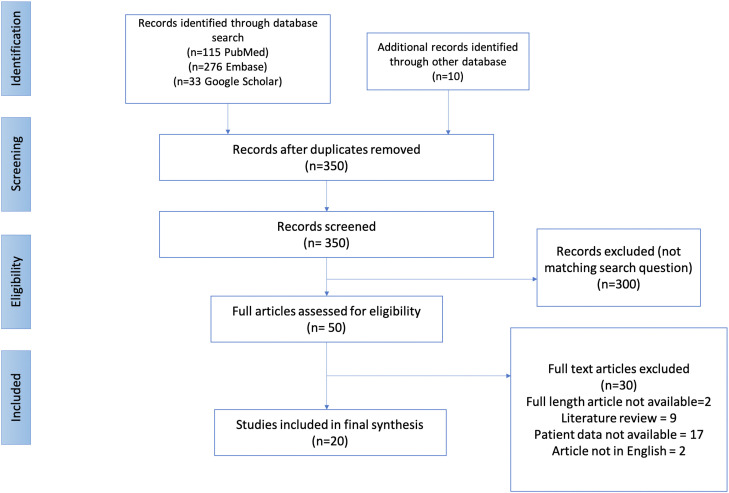

On primary keyword search, a total of 434 studies were identified. A total of 20 studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria were selected for final analysis, which included 286 patients in whom thromboembolic complications were reported after vaccination (Fig. 2 ). All the studies were retrospective in nature, the majority being case reports or case series published in 2021(Supplementary Table 1). Among the 20 studies, 6 were from Germany,7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 4 from the United States,13, 14, 15, 16 2 each from Italy,17 , 18 the United Kingdom,19 , 20and Denmark,21 , 22 and one each from France,23 Norway,24 Ireland,25 and European Union countries.26 The mean age of the study population was 48.5 ± 15.4 years. Females constituted 67.4% of the study group. In total, 13% of patients had risk factors for development of thrombosis, whereas 1.1% patients had a past history of venous/arterial thrombosis (Table I ). Two patients among the entire study cohort were known to have thrombophilia. Majority of the patients received the AstraZeneca vaccine (93.7%) followed by Johnson & Johnson (5.6%) and Pfizer (0.7%). The mean time of thrombotic events from the day of vaccination was 10.8 ± 7.2 days.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA flowchart for selected studies. PRISMA, preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis

Table I.

Baseline demographics of the patients who had thrombotic events after COVID-19 vaccination

| Characteristics | Number of studies included (n = 20) | Pooled incidence as per total no of thrombotic events (n = 286) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 19 | 48.5 ± 15.4 |

| Females | 16 | 87/129 (67.4) |

| History of prior thrombosis | 17 | 1/89 (1.1) |

| Risk factors for thrombosis(OCP use/HRT) | 18 | 16/116 (13.8) |

| Known thrombophilia | 20 | 2/286 (0.6) |

| COVID vaccine received | ||

| AstraZeneca | 16 | 268/286 (93.7) |

| Johnson & Johnson | 3 | 16/286 (5.6) |

| Pfizer | 2 | 2/286 (0.7) |

| Time of event after vaccination, days | 18 | 10.8 ± 7.2 |

| Treatment | ||

| UFH/LMWH | 7 | 20/38 (52.6) |

| Nonheparin anticoagulantsa | 5 | 13/32 (40.6) |

| Steroids | 5 | 13/31 (41.9) |

| IVIg | 6 | 16/36 (44.4) |

| Death | 19 | 43/144 (29.9) |

Age and time of event after vaccination are expressed in mean ± SD. Rest all values are expressed in percentages.

HRT, hormone replacement therapy; OCP, oral contraceptive pill.

Nonheparin anticoagulants include fondaparinux and argatroban.

Venous thrombosis was more common in the study cohort than arterial thrombosis (74.8% vs. 27.9%). Among the patients with arterial thrombosis, myocardial infarction was the most common presentation (20.1%). Ischemic stroke (8.02%) and peripheral arterial thrombosis (1.4%) were less common in the study group (Table II ). Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CST) was the most common manifestation (28.3%) of venous thrombosis in patients after COVID-19 vaccination followed by deep vein thrombosis (19.2%). Pulmonary thromboembolism and splanchnic venous thrombosis were also noted in 15.7% and 13.6% patients, respectively. Patients with splanchnic venous thrombosis were noted to have portal vein and mesenteric vein thrombosis. Among the studies published, Pottegard et al. reported the highest number of thrombotic events (n = 142), among which myocardial infarction was the most common manifestation (n = 52) followed by deep venous thrombosis (n = 22) (Supplementary Table 2). Thrombosis at other sites (not defined) was noted in 17% of patients. Among this group, one patient presented with complaints of conjunctival congestion, retro-orbital pain, and diplopia, 10 days after receiving the first dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. On evaluation, the patient was noted to have bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis.12 Another patient developed sudden onset chest pain 30 min after vaccination with electrocardiographic changes suggestive of inferior wall myocardial infarction. Coronary angiogram revealed thrombotic occlusions of the distal part of major coronary arteries.14 Concurrent thrombosis at more than one site was noted in 15.4% of the study group. Among the patients presenting with thromboembolism after vaccination, 49% were noted to have thrombocytopenia. A vast majority of patients (78.6%) were found to have antibodies against PF4. Nine studies provided data on D-dimer and fibrinogen levels in patients presenting with thromboembolism (Table II). D-dimer levels were significantly elevated with a mean value of 36.8 ± 31.1 mg/L. Fibrinogen levels were also found to be low constantly in these patients, with a mean nadir of 1.5 ± 0.28 g/L.

Table II.

Incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis noted in patients after COVID-19 vaccination

| Thrombotic events | Number of studies included (n = 20) | Pooled incidence as per total number of thromboembolic events after vaccination (n = 286) |

|---|---|---|

| Arterial thrombosis | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 19 | 55/274 (20.1) |

| Ischemic stroke | 19 | 22/274 (8.02) |

| Peripheral artery thrombosis | 16 | 3/220 (1.4) |

| Venous thrombosis | ||

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 20 | 45/286 (15.7) |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 18 | 49/254 (19.2) |

| Cerebral sinus thrombosis | 20 | 81/286 (28.3) |

| Splanchnic vein thrombosisa | 20 | 39/286 (13.6) |

| Other site thrombosisb | 17 | 42/247 (17) |

| Multiple site thrombosis | 17 | 39/253 (15.4) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 18 | 126/257 (49) |

| Anti-PF4 antibodies | 15 | 81/103 (78.6) |

| D-Dimer, mg/L | 9 | 36.8 ± 31.1 |

| Fibrinogen nadir, g/L | 9 | 1.5 ± 0.28 |

All data are expressed as percentages except D-dimer and fibrinogen, which are expressed as mean ± SD.

Splanchnic vein thrombosis includes portal vein and mesenteric vein thrombosis.

One patient had thrombosis of the superior orbital vein.

Thromboembolic events were most commonly (93.7%) reported after the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 n Cov-19 vaccine (Table III ). Among the site of thrombosis, cerebral venous sinus was the most common site (25.3%) followed by the coronary tree (20.1%). Pulmonary thromboembolism and deep venous thrombosis were noted in 14.9% and 16.4%, respectively, after receiving the AstraZeneca vaccine. The least number of thromboembolic events (n = 3) was reported after Pfizer vaccine administration, with one patient each presenting with myocardial infarction, pulmonary thromboembolism, and CST. One patient presented with bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis after receiving the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 n Cov-19 vaccine, a very uncommon manifestation.

Table III.

Incidence of arterial and venous thrombosis at different locations in patients receiving COVID-19 vaccines

| Thrombotic events | AstraZeneca (n = 268) | J & J (n = 16) | Pfizer (n = 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arterial thrombosis | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 54 | 0 | 1 |

| Ischemic stroke | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral artery thrombosis | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Venous thrombosis | |||

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 40 | 4 | 1 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 44 | 5 | 0 |

| Cerebral sinus thrombosis | 68 | 12 | 1 |

| Splanchnic vein thrombosisa | 36 | 2 | 0 |

| Other site thrombosisb | 42 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple site thrombosis | 31 | 8 | 1 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 110 | 16 | 1 |

| Anti-PF4 antibodies | 69 | 12 | NA |

AstraZeneca, Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine; J & J, Johnson and Johnson vaccine; Pfizer, Pfizer mRNA vaccine.

Splanchnic vein thrombosis includes portal vein and mesenteric vein thrombosis.

One patient had thrombosis of the superior orbital vein.

Patients who presented with thromboembolism after vaccination were commonly treated with unfractionated heparin/low-molecular-weight heparin (UFH/LMWH) (52.6%). A proportion of patients (40.6%) also received nonheparin anticoagulants like argatroban and fondaparinux. Oral or intravenous steroid was administered in 41.9% of patients, whereas intravenous immunoglobulin was used in 44.4% (Table I). Among the patients presenting with thromboembolism, mortality was noted in 29.9%, with all deaths occurring during the hospital stay.

Discussion

The current systematic review aims to evaluate the thromboembolic events reported after COVID-19 vaccination, first of its kind. The reported cases of postvaccination thromboembolism mainly comprised of young patients (mean age = 48.5 years) with a female predominance. The large World Health Organization (WHO) vigilance database on adverse events after COVID-19 vaccination also showed a female preponderance.5 All patients had received the first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, whereas some had received both the doses. Majority of patients did not have any prior history of thromboembolism or any risk factors for thrombosis. AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 n Cov-19 was the most commonly administered vaccine. Patients presented early after vaccination with thromboembolic events (mean = 10.8 days).

Venous thrombosis was more commonly seen after vaccination than arterial thrombosis. Among the venous thrombosis group, CST was the most common presentation followed by deep venous thrombosis. This was in contrast to the findings noted in the WHO VigiBase (global database for individual case safety reports),5 where pulmonary thromboembolism (18%) and deep venous thrombosis (17.7%) were the common manifestation in the venous thrombosis group. The incidence of CST was 0.9% in VigiBase, which is extremely low. This was in contrast to the high incidence of CST noted in the current study. A small proportion of patients (13.6%) were also noted to have splanchnic venous thrombosis in our study, a group which was not clearly defined in VigiBase. Myocardial infarction was the most common manifestation in the arterial thrombosis group in our study, followed by ischemic stroke. On the contrary, ischemic stroke was more common (34.3%) than myocardial infarction (12.7%) in WHO VigiBase.5 It must be kept in mind that myocardial infarction in these patients can be a result of de novo coronary thrombus or a pre-existing vulnerable plaque rupture secondary to a sympathetic stress response to the vaccine. However, it is difficult to identify the exact mechanism, and the data regarding the same have not been provided in most of the studies. A small proportion of patients were noted to have peripheral artery thrombosis in our study, who presented with features of acute limb ischemia. Two patients had thrombotic thrombocytopenia without evidence of thrombosis in any major vascular bed. Concurrent thrombosis at more than one site was seen in about one-sixth of our study population, indicating the presence of a systemic hypercoagulable state. Concomitant thrombosis rates were much lower in VigiBase, with 2.4% patients reporting multisite thrombosis.

Both arterial and venous thrombotic events were most commonly seen after administration of the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1 n Cov-19 vaccine, while a least number of thrombotic events were noted after the administration of the Pfizer vaccine. In VigiBase, the AstraZeneca vaccine was noted to have highest venous thrombotic events, whereas arterial thrombotic events were significantly higher after Pfizer vaccine administration, stroke being the most common. Cerebral venous thrombosis was the most common presentation after AstraZeneca vaccine administration followed by myocardial infarction in the current study. However, in VigiBase, the AstraZeneca vaccine was most commonly associated with stroke and pulmonary embolism. This difference could arise due to the variability in reporting of cases and determination of causal association between vaccination and thromboembolic events. Pfizer vaccine administration was associated with a high proportion of stroke (about half of all arterial thrombotic events). This was in contrast to our study, where no stroke events were noted after Pfizer vaccine administration. Multisite thrombosis was also more with the AstraZeneca vaccine in our study, whereas the Moderna vaccine showed highest concomitant thrombosis rates (2.4%) in VigiBase. Time to thrombotic events was similar among all vaccines reported in VigiBase and was lower than the time period noted in our study (median = 3.5 days vs. median = 9.6 days).

A significant proportion of patients presenting with thrombosis were also noted to have thrombocytopenia. These patients were also noted to have elevated D-dimer and reduced fibrinogen levels. Multiple hypotheses have been proposed explaining the association of thromboembolic events and thrombocytopenia after vaccination. The incidence of thromboembolic events along with thrombocytopenia and elevated D-dimer closely resembles the clinical presentation of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT). HIT is mediated by generation of pathogenic antibodies against the heparin–PF4 complex, which releases more PF4 from platelets and produces a hypercoagulable state.27 Majority of patients who had thromboembolism after vaccination had anti-PF4 antibodies. As majority of events were noted after AstraZeneca vaccine administration, some pathogenic link exists between vaccine components and generation of anti-PF4 antibodies. The AstraZeneca vaccine is known to contain the adenovirus as the vector. It has been proposed that negatively charged adenoviral particles can bind to positively charged PF4, leading to formation of an immunogenic complex (similar to the heparin–PF4 complex) causing further platelet activation and widespread thrombosis.28 This has been termed as vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia (VITT). Free adenoviral DNA particles, which may be present in the vaccine, can also precipitate VITT as nucleic acids can form a complex with PF4.29 There is potential for direct interaction between adenoviral particles and platelets, using the coxsackie and adenovirus receptor.30 Binding of adenoviral particles to platelets can lead to platelet activation and release of PF4, which can activate the coagulation cascade leading to thrombosis.31 , 32 Cross-reactivity between antibodies against Sars-Cov-2 spike protein, generated after vaccination, and PF4 is also hypothesized as the potential mechanism for thrombocytopenia and thrombotic events.33 The type of spike protein encoded varies among the mRNA vaccine (Pfizer and Moderna), Ad26.COV2 vector vaccine (Johnson & Johnson), and AZD1222 vaccine (AstraZeneca).34 , 35 This may be the reason for variability in thrombotic events noted after different vaccines. Antiadenoviral antibodies are generated after administration of the AZD1222 vaccine.36 These antibodies may cross-react with platelets and cause VITT. However, further studies are required to prove this hypothesis.

Prompt recognition of the COVID-19 vaccine as the causal agent of thromboembolism is warranted. Patients presenting with thrombosis, thrombocytopenia, and positive PF4 antibodies after exposure to the COVID-19 vaccine are likely to be having VITT.37 Further evaluation of the patient with complete blood count, peripheral smear, and D-dimer and fibrinogen levels along with imaging assessment of thrombosis is also imperative. As the likely mechanism of thrombosis is immune-mediated damage, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) and steroids are recommended as the first line of management. It is advisable to avoid heparin and heparin-related anticoagulants as well as platelet transfusions, as they can further precipitate thrombosis. Nonheparin anticoagulants like argatroban are preferable. In the current study, a significant proportion of patients with thrombosis after vaccination were treated with UFH/LMWH, whereas others received argatroban and fondaparinux. Steroids and IVIg were also used in acute settings. Despite prompt recognition and early management, a significant proportion of patients can develop disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) leading to widespread thrombosis and bleeding at the same time, resulting in mortality. In the current cohort of patients, 19 patients were reported to have DIC after COVID-19 vaccination. Thus, early recognition and management are key determinants of outcome in these patients.

Despite the incidence of thromboembolic events noted after COVID-19 vaccination, the benefits associated with vaccination are many folds higher than the risk. Moreover, the risk of developing thrombotic events after COVID-19 vaccination is almost similar to the risk of thrombosis in the general population. Therefore, administration of COVID-19 vaccines should not be hampered due to the minimal risk of thromboembolism, mainly associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine. Understanding the related complications associated with vaccination is important to effectively manage these events in the small cohort. Development of immunity among the general population is the need of the hour and seems to be the only way to curb and control this ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The current study has inherent limitations. Firstly, there is lack of hard evidence to suggest the causal relationship between vaccination and thromboembolic events. However, the temporal association between the 2 events along with lack of pre-existing thromboembolic risk factors in these patients makes the association likely. So, the results of our study should be interpreted with caution. Secondly, the data extracted are predominantly from sporadic case reports and case series. This prevents the generalization of the current findings to the entire community. Thirdly, the majority of data reported are from Europe and America, whereas there is a paucity of data from other regions of the world. Whether this is due to lack of reporting of adverse events from other regions or actual ethnic differences exist needs to be evaluated. Also, data regarding adverse events after administration of the mRNA vaccine are sparse. Long-term follow-up studies are required to evaluate adverse effects after mRNA vaccines, if any. Lastly, the WHO VigiBase was not included in the current study as it had a huge data set which was likely to skew the results. Moreover, data about individual cases were not provided. It is possible that many cases, which were reported only to WHO VigiBase and not published elsewhere, were missed in the current analysis. Taking into context all these factors, we believe that the benefits of COVID-19 vaccination definitely outweigh the minor risks associated with it. However, it is equally important to understand and study the complications which can be associated with these vaccines to enable the clinicians manage them effectively.

Conclusion

Thromboembolic events can occur after COVID-19 vaccination, most commonly after AstraZeneca vaccine administration. Cerebral venous thrombosis is the most common presentation noted among reported thromboembolism cases. Prompt recognition and early initiation of therapy hold the key to manage this uncommon adverse effect of COVID-19 vaccination.

Footnotes

A.M. and V.O are contributed equally and share the first authorship.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial sector, or not-for-profit sectors.

Appendix

Supplementary Table 1.

Baseline details of studies selected for final analysis

| SL No. | Date of publication | First Author | Type of study | Region of study | Number of thrombotic events | Age (years) | Covid-19 vaccine | Duration post vaccination (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 19/05/21 | Gras-Champel et al.23 | Retrospective | France | 27 | 53.4 | AZ | 11 |

| 2. | 16/04/21 | Scully et al.19 | Retrospective | UK | 22 | 46 | AZ | 12 |

| 3. | 09/04/21 | Schultz et al.24 | Retrospective | Norway | 5 | 40.8 | AZ | 8.4 |

| 4. | 09/04/21 | Greinacher et al.7 | Retrospective | Germany | 11 | 36 | AZ | 9.3 |

| 5. | 25/05/21 | Ryan et al.25 | Retrospective | Ireland | 1 | 35 | AZ | 14 |

| 6. | 20/04/21 | Blauenfeldt et al.21 | Retrospective | Denmark | 1 | 60 | AZ | 7 |

| 7. | 22/05/21 | Graf et al.8 | Retrospective | Germany | 1 | 29 | AZ | 14 |

| 8. | 20/05/21 | Althaus et al.9 | Retrospective | Germany | 8 | 40 | AZ | 10.4 |

| 9. | 10/05/21 | Ciccone et al.17 | Retrospective | Italy | 11 | 47.9 | AZ/PZ | 9 |

| 10. | 04/05/21 | Yocum et al.13 | Retrospective | USA | 1 | 62 | J&J | 37 |

| 11. | 10/05/21 | Tajstra et al.14 | Retrospective | USA | 1 | 86 | PZ | 1 |

| 12. | 30/04/21 | Shay et al.15 | Retrospective | USA | 3 | 45 | J&J | 9 |

| 13. | 05/05/21 | Pottegard et al.22 | Retrospective | Denmark | 142 | NA | AZ | NA |

| 14. | 30/04/21 | See et al.16 | Retrospective | USA | 12 | 35 | J&J | 8.8 |

| 15. | 09/04/21 | Tobaiqy et al.26 | Retrospective | Europe | 28 | 77.5 | AZ | NA |

| 16. | 10/04/21 | Wolf et al.10 | Retrospective | Germany | 3 | 35 | AZ | 6 |

| 17. | 11/04/21 | D’agostino et al.18 | Retrospective | Italy | 1 | 54 | AZ | 12 |

| 18. | 28/04/21 | Tiede et al.11 | Retrospective | Germany | 5 | 55 | AZ | 8.4 |

| 19. | 01/05/21 | Bayas et al.12 | Retrospective | Germany | 1 | 55 | AZ | 10 |

| 20. | 20/04/21 | Mehta et al.20 | Retrospective | UK | 2 | 29 | AZ | 7.5 |

AZ, Astra Zeneca vaccine, J&J, Johnson and Johnson vaccine, PZ, Pfizer mRNA vaccine.

Supplementary Table 2.

Incidence and location of thrombotic events in individual studies

| SL No. | First Author | Covid-19 vaccine | MI | Stroke | Peripheral thrombosis | PTE | DVT | CST | Splanchnic thrombosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Gras-Champel et al.23 | AZ | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 11 | 17 |

| 2. | Scully et al.19 | AZ | 1 | 2 | NA | 4 | 1 | 13 | 2 |

| 3. | Schultz et al.24 | AZ | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 4 | 1 |

| 4. | Greinacher et al.7 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 |

| 5. | Ryan et al.25 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. | Blauenfeldt et al.21 | AZ | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7. | Graf et al.8 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. | Althaus et al.9 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| 9. | Ciccone et al.17 | AZ/PZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 11 | 5 |

| 10. | Yocum et al.13 | J&J | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11. | Tajstra et al.14 | PZ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12. | Shay et al.15 | J&J | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 13. | Pottegard et al.22 | AZ | 52 | 16 | 0 | 21 | 22 | 7 | 5 |

| 14. | See et al.16 | J&J | NA | NA | NA | 3 | 3 | 12 | 2 |

| 15. | Tobaiqy et al.26 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 18 | 1 | 0 |

| 16. | Wolf et al.10 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| 17. | D’agostino et al.18 | AZ | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 18. | Tiede et al.11 | AZ | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 19. | Bayas et al.12 | AZ | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20. | Mehta et al.20 | AZ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

References

- 1.Guan W., Ni Z., Hu Y., et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. New Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mani A. COVID-19 and cardiac health: A review. 2021. https://www.j-pcs.org/article.asp?issn=2395-5414

- 3.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., et al. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur R.J., Dutta S., Bhardwaj P., et al. Adverse events reported from COVID-19 vaccine Trials: a systematic review. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2021;36:427–439. doi: 10.1007/s12291-021-00968-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smadja D.M., Yue Q.-Y., Chocron R., et al. Vaccination against COVID-19: insight from arterial and venous thrombosis occurrence using data from VigiBase. Eur Respir J. 2021;58:2100956. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00956-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Study quality assessment tools | NHLBI, NIH. 2021. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 7.Greinacher A., Thiele T., Warkentin T.E., et al. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graf T., Thiele T., Klingebiel R., et al. Immediate high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins followed by direct thrombin-inhibitor treatment is crucial for survival in Sars-Covid-19-adenoviral vector vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia VITT with cerebral sinus venous and portal vein thrombosis. J Neurol. 2021;268:4483–4485. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10599-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Althaus K., Möller P., Uzun G., et al. Antibody-mediated procoagulant platelets in SARS-CoV-2- vaccination associated immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. Haematologica. 2021;106:2170–2179. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolf M.E., Luz B., Niehaus L., et al. Thrombocytopenia and intracranial venous sinus thrombosis after “COVID-19 vaccine AstraZeneca” exposure. J Clin Med. 2021;10:1599. doi: 10.3390/jcm10081599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiede A., Sachs U.J., Czwalinna A., et al. Prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia after COVID-19 vaccine. Blood. 2021;138:350–353. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayas A., Menacher M., Christ M., et al. Bilateral superior ophthalmic vein thrombosis, ischaemic stroke, and immune thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. Lancet. 2021;397:e11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00872-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yocum A., Simon E.L. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura after Ad26.COV2-S vaccination. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;49:441.e3–441.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tajstra M., Jaroszewicz J., Gąsior M. Acute coronary tree thrombosis after vaccination for COVID-19. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e103–e104. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shay D.K., Gee J., Su J.R., et al. Safety monitoring of the Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) COVID-19 vaccine — United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:680–684. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7018e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.See I., Su J.R., Lale A., et al. US case reports of cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with thrombocytopenia after Ad26.COV2.S vaccination, march 2 to April 21, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325:2448–2456. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.7517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciccone A., Zanotti B. The importance of recognizing cerebral venous thrombosis following anti-COVID-19 vaccination. Eur J Intern Med. 2021;89:115–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Agostino V., Caranci F., Negro A., et al. A rare case of cerebral venous thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulation temporally associated to the COVID-19 vaccine administration. J Pers Med. 2021;11:285. doi: 10.3390/jpm11040285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scully M., Singh D., Lown R., et al. Pathologic antibodies to platelet factor 4 after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2202–2211. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta P.R., Apap Mangion S., Benger M., et al. Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after COVID-19 vaccination – a report of two UK cases. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;95:514–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blauenfeldt R.A., Kristensen S.R., Ernstsen S.L., et al. Thrombocytopenia with acute ischemic stroke and bleeding in a patient newly vaccinated with an adenoviral vector-based COVID-19 vaccine. J Thromb Haemost. 2021;19:1771–1775. doi: 10.1111/jth.15347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pottegård A., Lund L.C., Karlstad Ø., et al. Arterial events, venous thromboembolism, thrombocytopenia, and bleeding after vaccination with Oxford-AstraZeneca ChAdOx1-S in Denmark and Norway: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2021;373:n1114. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gras-Champel V., Liabeuf S., Baud M., et al. Atypical thrombosis associated with VaxZevria® (AstraZeneca) vaccine: data from the French Network of regional pharmacovigilance centres. Therapies. 2021;76:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.therap.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schultz N.H., Sørvoll I.H., Michelsen A.E., et al. Thrombosis and thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2124–2130. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryan E., Benjamin D., McDonald I., et al. AZD1222 vaccine-related coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia without thrombosis in a young female. Br J Haematol. 2021;194:553–556. doi: 10.1111/bjh.17530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tobaiqy M., Elkout H., MacLure K. Analysis of thrombotic adverse reactions of COVID-19 AstraZeneca vaccine reported to EudraVigilance database. Vaccines (Basel) 2021;9:393. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9040393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arepally G.M. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2017;129:2864–2872. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-709873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soo-Yeon K., Whi-An K., Seung-Pil S., et al. Electrostatic interaction of tumor-targeting adenoviruses with aminoclay acquires enhanced infectivity to tumor cells inside the bladder and has better cytotoxic activity. Drug Deliv. 2018;25:49–58. doi: 10.1080/10717544.2017.1413450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaax M.E., Krauel K., Marschall T., et al. Complex formation with nucleic acids and aptamers alters the antigenic properties of platelet factor 4. Blood. 2013;122:272–281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-478966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupalo E., Buriachkovskaia L., Othman M. Human platelets express CAR with localization at the sites of intercellular interaction. Virol J. 2011;8:456. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin Y.-Y., Yu X.-N., Qu Z.-Y., et al. Adenovirus type 3 induces platelet activation in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:370–374. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2013.1805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stone D., Liu Y., Shayakhmetov D., et al. Adenovirus-platelet interaction in blood causes virus sequestration to the reticuloendothelial system of the liver. J Virol. 2007;81:4866–4871. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02819-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Anti-Platelet Factor 4 Antibody Responses Induced by COVID-19 Disease and ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. 2021. https://www.researchsquare.com

- 34.Corbett K.S., Edwards D.K., Leist S.R., et al. SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine design enabled by prototype pathogen preparedness. Nature. 2020;586:567–571. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2622-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinke B., Lucy R., van der Lubbey J.E.M., et al. Ad26 vector-based COVID-19 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike immunogen induces potent humoral and cellular immune responses. NPJ Vaccines. 2020;5:91. doi: 10.1038/s41541-020-00243-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett J.R., Belij-Rammerstorfer S., Dold C., et al. Phase 1/2 trial of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 with a booster dose induces multifunctional antibody responses. Nat Med. 2021;27:279–288. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-01179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Long B., Bridwell R., Gottlieb M. Thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome associated with COVID-19 vaccines. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;49:58–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]