Background:

Several studies have found that among patients testing positive for COVID-19 within a health care system, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic patients are more likely than non-Hispanic White patients to be hospitalized. However, previous studies have looked at odds of being admitted using all positive tests in the system and not only those seeking care in the emergency department (ED).

Objective:

This study examined racial/ethnic differences in COVID-19 hospitalizations and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions among patients seeking care for COVID-19 in the ED.

Research Design:

Electronic health records (n=7549) were collected from COVID-19 confirmed patients that visited an ED of an urban health care system in the Chicago area between March 2020 and February 2021.

Results:

After adjusting for possible confounders, White patients had 2.2 times the odds of being admitted to the hospital and 1.5 times the odds of being admitted to the ICU than Black patients. There were no observed differences between White and Hispanic patients.

Conclusions:

White patients were more likely than Black patients to be hospitalized after presenting to the ED with COVID-19 and more likely to be admitted directly to the ICU. This finding may be due to racial/ethnic differences in severity of disease upon ED presentation, racial and ethnic differences in access to COVID-19 primary care and/or implicit bias impacting clinical decision-making.

Key Words: COVID-19, hospitalization, ICU admissions, health disparities, racial/ethnic disparities

Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 admissions were reported from the earliest days of the pandemic in early 2020 and have persisted, with Black and Hispanic patients experiencing 2–3 times the rates of COVID-19-related hospital admission as White patients.1 In Chicago, Illinois, by June 2021, there were over 283,000 COVID-19 cases, with over 27,500 of these cases needing hospitalization and with over 5000 resulting in deaths.2 Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients made up a majority of the COVID-19 positive cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in Chicago and the surrounding areas.3

The early history of COVID-19 hospital admission rates among racial and ethnic groups has been well studied in the literature.4 Patients who live in predominantly Black neighborhoods had more complications, hospital admissions, and higher mortality due to COVID-19 than patients from predominantly White neighborhoods.5,6 Researchers have hypothesized that these discrepancies could be due to Black patients presenting to the hospital later in the disease course7 or with more comorbid conditions.8,9 This is consistent with other evidence showing that Black patients are more likely than other groups to delay emergency medical care.10

The goal of this study was to address the question of whether Black and Hispanic individuals are more likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 among patients seeking care in the emergency department (ED). We studied hospitalization rates among patients with COVID-19 who were seeking care in 1 of 3 EDs of a large academic health care system in the Chicago metropolitan area. Using hospitalization from the ED as a proxy for severity of COVID-19 upon arrival at the ED, we compared rates of hospitalization among White, Black, and Hispanic ED patients with a positive COVID-19 test. We defined patients seeking COVID-19 care in the ED as our study population to assure that we captured all the immediate hospitalizations within the population. Recent data from the Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance (EDBA) indicate that only 2.8% of patients are transferred from an ED to a different hospital for admission.11 We hypothesized that, consistent with other studies, Black and Hispanic patients would have more severe infection than White patients upon arrival at the ED, which would result in higher hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) admission rates.

METHODS

Data Source

This study was conducted using electronic health record (EHR) data for patient encounters within the Rush University System for Health (RUSH) which consists of 1 tertiary academic medical center in Chicago and 2 community hospitals in the Chicago suburbs, each with their own ED. Data from the system-side EHR were collected for patient encounters from March 2020 to February 2021.

Patients were included in this study if they had a confirmed COVID-19 positive test in any 1 of RUSH’s 3 EDs or confirmed positive from a test outside the ED within a week before seeking care in the ED. The analysis included only the first COVID-19 confirmed visit to an ED. Patients were excluded if they were under 18 years old (n=448), left the ED against medical advice (n=60), or were pregnant and transferred into the labor and delivery unit (n=59). Because the focus of this study was on non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic patients who presented to a RUSH ED, individuals who self-identified as any other race and ethnicity (which included those who identified as non-Hispanics and other, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Other or unknown) were excluded (n=765) as well as patients transferred from other acute care hospitals, nursing homes, and skilled nursing facilities who were not seen in a RUSH ED during that visit but were admitted directly into a hospital. This study was approved by the Rush University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

ED Discharge Disposition

The primary outcome was ED discharge disposition, classified as either admitted as an inpatient to the hospital or discharged home from the ED. The secondary outcome, for patients admitted to the hospital, was whether the patient was admitted to a general acute care unit or to the ICU directly from the ED. COVID-19 confirmed patients who died while in the ED were classified with the patients admitted to the ICU due to the small number of records (n=8). Patients who were seen in the ED and then discharged home (ie, without being admitted) are referred to as “ED Only” patients. If a patient was transferred to the medical observation unit, they were classified based on whether the patient was discharged home from the medical observation unit (ie, ED only) or was subsequently admitted as an inpatient.

Race and Ethnicity

A patient’s race and ethnicity were defined using the self-identified field in the EHR. Race and ethnicity are self-reported to the ED registration representative and entered into the EHR. If the patient is already in the system, the registration representative asks the patient to confirm their race and ethnicity. In the EHR, race and ethnicity are reported separately. Patients reporting Hispanic ethnicity were classified as Hispanic, and non-Hispanic patients were classified by their self-identified race (ie, non-Hispanic White or non-Hispanic Black, subsequently referred to as White or Black, respectively).

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic characteristics, including age, sex, and insurance type, were documented for each encounter. Clinical characteristics included both the patient’s chronic disease history (comorbidities) and clinical measures documented in the ED. The patient’s comorbidities were based on Clinical Classifications Software Refined (CCSR) categories, which are categorized using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes of the patient encounter.12 The comorbidities included in this study were heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, asthma, kidney disease, neurological conditions, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, liver disease, and cerebrovascular disease. Obesity was defined as patient body mass index ≥30 taken at the ED encounter or the presence of an obesity ICD-10 diagnosis code. Count of comorbidities is a count of all comorbidities as well as obesity for each patient. Clinical measures related to COVID-19 and measured in the ED included the lowest peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) and the highest respiratory rate (RR) recorded during the patient’s time in the ED. SpO2 was dichotomized into ≥92 and <92 and RR was dichotomized into ≤20 and >20. SpO2 <92 and RR >20 are values associated with increased mortality.13 Because high poverty community areas were more likely to experience worse COVID-19 outcomes,14 the percentage of the population below the federal poverty level in each census tract was abstracted from the 2019 American Community Survey 5-year estimates at the census tract level. Each patient’s home address was then geocoded using ArcGIS to the census tract level and merged with the corresponding poverty rate for that census tract.

Other patient characteristics included any visit to a RUSH ED in the prior 24 months and whether a patient visited a RUSH primary care physician (PCP) in the 12 months before the patient’s ED encounter date for COVID-19. To account for changes in government and hospital policy and community outbreaks over the course of the pandemic, the month that the patient was seen at the ED was also included.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. A series of analyses were conducted to examine the association of race and ethnicity with ED discharge disposition. All patient characteristics were examined using descriptive statistics, including frequency distribution, mean (SD), or median (interquartile range) by race and ethnicity. χ2 tests and Wilcoxson rank tests were used to detect unadjusted statistical differences. A series of multivariable analyses was conducted to examine the adjusted association of race and ethnicity with ED discharge disposition. First, the relationship between patient race and ethnicity and odds of hospital admission was explored. Next, three logistic regression models were constructed with ED discharge disposition as the outcome and the following variables as predictors: Model 1 included only race and ethnicity; Model 2 included race and ethnicity and other demographic characteristics; Model 3 included race and ethnicity, other demographic characteristics, and patient’s comorbidities. Second, for the subset of patients admitted to the hospital, three similar models were constructed to predict whether the patient was admitted to the ICU immediately versus admitted to a general acute care unit. All demographic characteristics were chosen a priori. Only the comorbidities with a significant association (P<0.05) with the outcomes in an unadjusted analysis were included in the models. To control for differences in clinical practice and policies over time among the EDs, as well as the residence of the patients, the ED where the patient was seen and encounter month were included as a cluster effect in all models.

Sensitivity Analyses

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the results of the models stratifying by RR. Since RR >20 is a known predictor of mortality, stratifying the model by RR will allow us to examine the model with patients who were more likely to be admitted.13 Thus, the same variables used in Model 3, mentioned above, were used to examine whether the relationships vary dependent on respiratory rate (≥21 and ≤20).

RESULTS

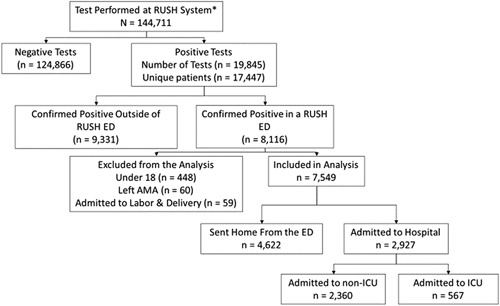

Of 17,447 patients who tested positive for COVID-19 in the RUSH system, 7549 visited a RUSH ED with a positive case of COVID-19 and were included in this study (Fig. 1). Of the COVID-19 positive patients seen in the ED, 39% (n=2927) were admitted to the hospital from the ED. In addition, 19% (n=567) of those admitted to the hospital were admitted directly to the ICU. Among the patients in the study, 49.8% were older than age 50, 16.5% were uninsured, and the average number of comorbidities was 2 (SD: 2.0). About 29% of the patients had seen a RUSH PCP in the prior 12 months and 64.9% had visited a RUSH ED within the 24 months before the ED encounter date (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of patients entering the study. *Test only include patients who self-identified as White, Black, or Hispanic.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of COVID-19 Positive Patients Seen at a RUSH ED in the Chicago, IL, Area From March 2020 to February 2021

| Patient Characteristics | Total, N (%) | White, n (%) | Black, n (%) | Hispanic, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 7549 | 1217 (16.1) | 3027 (40.1) | 3305 (43.8) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 4051 (53.7) | 629 (51.7) | 1770 (58.5) | 1652 (50.0) |

| Male | 3497 (46.3) | 588 (48.3) | 1257 (41.5) | 1652 (50.0) |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 18–35 | 1930 (25.6) | 170 (14.0) | 867 (28.6) | 893 (27.0) |

| 35–50 | 1859 (24.6) | 191 (15.7) | 761 (25.1) | 907 (27.4) |

| 51–65 | 1900 (25.2) | 292 (24.0) | 713 (23.6) | 895 (27.1) |

| 65+ | 1860 (24.6) | 564 (46.3) | 686 (22.7) | 610 (18.5) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 2673 (35.4) | 484 (39.8) | 982 (32.4) | 1207 (36.5) |

| Medicaid | 1831 (24.3) | 146 (12.0) | 973 (32.1) | 712 (21.5) |

| Medicare | 1802 (23.9) | 512 (42.1) | 764 (25.2) | 526 (15.9) |

| Uninsured* | 1243 (16.5) | 75 ( 6.2) | 308 (10.2) | 860 (26.0) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Heart disease | 3566 (47.2) | 753 (61.9) | 1565 (51.7) | 1248 (37.8) |

| Hypertension | 3251 (43.1) | 661 (54.3) | 1467 (48.5) | 1123 (34.0) |

| Obesity | 2528 (33.5) | 356 (29.3) | 1243 (41.1) | 929 (28.1) |

| Diabetes | 2031 (26.9) | 299 (24.6) | 771 (25.5) | 961 (29.1) |

| Asthma | 960 (12.7) | 166 (13.6) | 526 (17.4) | 268 (8.1) |

| Kidney disease | 926 (12.3) | 202 (16.6) | 476 (15.7) | 248 (7.5) |

| Neurological conditions | 632 (8.4) | 171 (14.1) | 272 (9.0) | 189 (5.7) |

| COPD | 403 (5.3) | 141 (11.6) | 193 (6.4) | 69 (2.1) |

| Liver disease | 290 (3.8) | 52 (4.3) | 90 (3.0) | 148 (4.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 160 (2.1) | 38 (3.1) | 78 (2.6) | 44 (1.3) |

| Count of comorbidities (mean, SD) | 2.0 (2.0) | 2.4 (2.0) | 2.2 (2.1) | 1.7 (1.9) |

| SpO2 (<92) | 74 (1.0) | 27 (2.3) | 25 (0.8) | 19 (0.7) |

| RR (>20) | 2963 (63.6) | 546 (45.6) | 1170 (37.1) | 1220 (38.2) |

| ED visit in last 24 mo | 4900 (64.9) | 799 (65.7) | 1725 (57.0) | 2376 (71.9) |

| PCP visit in last 12 mo | 2211 (29.3) | 342 (28.1) | 965 (28.7) | 904 (24.8) |

| Percentage under poverty level (median, IQR) | 16.4 (8.4–26.7) | 6.8 (4.4–11.8) | 25.0 (12.8–37.3) | 15.4 (9.1–21.3) |

Uninsured includes self-pay and HRSA.

The bolded numbers indicate P-value <0.05 from comparison of the Black and Hispanic patient values versus White patient values.

COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; IQR, interquartile range; PCP, primary care physician; RR, respiratory rate; SD, standard deviation; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

The majority of the patients presenting to the ED were Black (40.1%) or Hispanic (43.8%) and 16.1% of the patients were White (Table 1). White patients were older: 46.3% were ≥65 compared with 18.5% of Hispanic and 22.7% of Black patients. A larger proportion of Hispanic patients was uninsured compared with White and Black patients (Whites: 6.2%; Blacks: 10.2%; and Hispanics: 26.0%). Heart disease, hypertension, and obesity were the most common comorbidities across all racial and ethnic groups. Black and Hispanic patients had fewer comorbidities than White patients. White patients were more likely than Black and Hispanic patients to have heart disease, hypertension, and kidney disease and more likely than Black patients to have liver disease. White patients were more likely than Black or Hispanic patients to have RR >20 and SpO2 <92. Hispanic patients were more likely and Black patients were less likely than White patients to have visited a RUSH ED in the prior 24 months (Hispanics: 71.9%; Whites: 65.7%; Blacks: 57.0%). Hispanic patients were less likely than White patients to have visited a RUSH PCP in the prior 12 months (Whites: 28.1%; Hispanics: 27.4%). The median neighborhood poverty rate was higher for Black and Hispanic patients than for White patients (Table 2). White patients (54.9%) were more likely than Black (32.8%) or Hispanic patients (38.3%) to be admitted. Older patients and those with more comorbidities were more likely to be admitted than younger, healthier patients. As expected, there were more patients with an RR >20 among hospitalized patients than ED only patients, but there were fewer patients with SpO2 <92 among hospitalized versus ED-only patients.

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by ED Discharge Disposition

| All Patients (n=7549) | All Hospital Admissions (n=2927) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | ED Only, n (%) | Admitted, n (%) | Admit Non-ICU, n (%) | Admit ICU, n (%) |

| Total | 4622 (61.2) | 2927 (38.8) | 2360 (80.6) | 567 (19.4) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 549 (45.1) | 668 (54.9)* | 571 (85.5) | 97 (14.5)* |

| Black | 2033 (67.2) | 994 (32.8) | 786 (79.1) | 208 (20.9) |

| Hispanic | 2040 (61.7) | 1265 (38.3) | 1003 (79.3) | 262 (20.7) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 2632 (65.0) | 1419 (35.0)* | 1181 (83.2) | 238 (16.8)* |

| Male | 1989 (56.9) | 1508 (43.1) | 1179 (78.2) | 329 (21.8) |

| Age (y) | ||||

| 18–35 | 1703 (88.2) | 227 (11.8)* | 181 (79.7) | 46 (20.3) |

| 35–50 | 1343 (72.2) | 516 (27.8) | 413 (80.0) | 103 (20.0) |

| 51–65 | 969 (51.0) | 931 (49.0) | 745 (80.0) | 186 (20.0) |

| 65+ | 607 (32.6) | 1253 (67.4) | 1021 (81.5) | 232 (18.5) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Private | 1746 (65.3) | 927 (34.7)* | 764 (82.4) | 163 (17.6) |

| Medicaid | 1331 (72.7) | 500 (27.3) | 394 (78.8) | 106 (21.2) |

| Medicare | 605 (33.6) | 1197 (66.4) | 968 (80.9) | 229 (19.1) |

| Uninsured* | 940 (75.6) | 303 (24.4) | 234 (77.2) | 69 (22.8) |

| Heart disease | 1418 (39.8) | 2148 (60.2)* | 1686 (78.5) | 462 (21.5)* |

| Diabetes | 780 (38.4) | 1251 (61.6)* | 964 (77.1) | 287 (22.9)* |

| Obesity | 965 (38.2) | 1563 (61.8)* | 1224 (78.3) | 339 (21.7)* |

| Kidney disease | 160 (17.3) | 766 (82.7)* | 589 (76.9) | 177 (23.1)* |

| COPD | 85 (21.1) | 318 (78.9)* | 237 (74.5) | 81 (25.5)* |

| Liver disease | 68 (23.4) | 222 (76.6)* | 171 (77.0) | 51 (23.0) |

| Count of comorbidities † (mean, SD) | 1.3 (1.6) | 3.4 (2.0)* | 3.3 (2.0) | 4.0 (2.0)* |

| SpO2 (<92) | 38 (51.4) | 36 (48.7)* | 29 (80.6) | 7 (19.4) |

| RR (>20) | 904 (30.8) | 2032 (69.2)* | 1587 (78.1) | 445 (21.9)* |

| Percentage under poverty level (median, IQR) | 17.2 (8.9–28.7) | 15.2 (7.7–24.9)* | 14.3 (6.9–23.9) | 17.7 (10.3–29.4)* |

P-values <0.05 from comparing admitted versus ED only and admit ICU versus admit non-ICU, respectively.

Uninsured includes self-pay and HRSA.

COPD indicates chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit; IQR, interquartile range; RR, respiratory rate; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

Among the patients who were hospitalized, 80.6% were admitted to a non-ICU unit and 19.4% were admitted immediately into the ICU. Hispanic (20.7%) and Black (20.9%) patients were more likely than White (14.5%) patients to be admitted directly to the ICU. Patients admitted to the ICU had more comorbidities on average (Mean: 4.0; SD: 2.0) than those admitted to a general acute care unit (Mean: 3.3; SD: 2.0). Those admitted to ICU directly from the ED were more likely to come from neighborhoods with a higher poverty level.

In the unadjusted model (Model 1), both Black patients [odds ratio (OR): 0.35; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.30-0.41] and Hispanic patients (OR: 0.48; 95% CI: 0.42-0.56) were less likely to be admitted to the hospital than White patients (Table 3). After adjusting for demographic characteristics (Model 2) and patient’s comorbidities (Model 3), Black patients were still less likely to be admitted than White patients.

TABLE 3.

Association of Race/Ethnicity and Admission to Hospital From ED

| Patient Characteristics | Model 1: Race/Ethnicity only OR (95% CI) | Model 2: Model 1 w/ Demographic Characteristics OR (95% CI) | Model 3: Model 2 w/ Comorbidities OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black | 0.35 (0.30–0.41) | 0.64 (0.54–0.76) | 0.45 (0.37–0.55) |

| Hispanic | 0.48 (0.42–0.56) | 0.94 (0.81–1.11) | 0.92 (0.77–1.10) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Male | 1.45 (1.31–1.61) | 1.52 (1.35–1.71) | |

| Age* | 1.30 (1.28–1.33) | 1.24 (1.22–1.27) | |

| Insurance type | |||

| Private | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Medicaid | 0.97 (0.85–1.12) | 0.94 (0.80–1.10) | |

| Medicare | 1.18 (1.01–1.38) | 0.86 (0.72–1.02) | |

| Uninsured | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | |

| Percentage under poverty level* | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.95 (0.93–0.97) | |

| Obesity | 4.64 (4.09–5.27) | ||

| Heart disease | 1.62 (1.41–1.86) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.21 (1.06–1.38) | ||

| Kidney disease | 3.93 (3.20–4.82) | ||

| COPD | 2.45 (1.84–3.25) | ||

| Liver disease | 3.16 (2.30–4.34) | ||

| AUC † | 0.65 (0.63–0.66) | 0.80 (0.79–0.81) | 0.86 (0.86–0.87) |

Number is the odds ratio for 5-point increase.

Numbers shown are the AUC and 95% confidence limits.

Numbers in bold have P-values <0.05. All models used ED visited and ED encounter month as cluster effects; reference group for the outcome of all models is ED only.

AUC indicates area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio.

After adjusting for demographics and patient’s comorbidities, Black patients were less likely to be admitted to the ICU versus admitted to a non-ICU unit (Table 4). After stratifying the models by RR (Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/MLR/C433), Black patients were still less likely than White patients to be admitted and Hispanic patients were not different than White patients. In the RR ≤20 model, both Hispanic and Black patients were significantly less likely to be admitted.

TABLE 4.

Association of Race/Ethnicity and Admission to ICU Among Patients Admitted to the Hospital (ie, Admission to ICU vs. Admission to General Acute Care)

| Patient Characteristics | Model 1: Race/Ethnicity only OR (95% CI) | Model 2: Model 1 w/ Demographic Characteristics OR (95% CI) | Model 3: Model 2 w/ Comorbidities OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black | 0.93 (0.71–1.21) | 0.78 (0.58–1.06) | 0.68 (0.50–0.93) |

| Hispanic | 1.09 (0.84–1.41) | 0.93 (0.70–1.23) | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Male | 1.30 (1.07–1.57) | 1.29 (1.07–1.57) | |

| Age* | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | 0.95 (0.91–0.99) | |

| Insurance type | |||

| Private | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| Medicaid | 1.18 (0.89–1.55) | 1.06 (0.80–1.41) | |

| Medicare | 1.16 (0.88–1.51) | 0.99 (0.75–1.30) | |

| Uninsured | 1.44 (1.03–2.01) | 1.53 (1.08–2.15) | |

| Percentage under poverty level* | 1.05 (1.00–1.09) | 1.04 (0.99–1.08) | |

| Obesity | 1.07 (0.88–1.31) | ||

| Heart disease | 1.94 (1.48–2.55) | ||

| Diabetes | 1.32 (1.08–1.62) | ||

| Kidney disease | 1.15 (0.92–1.45) | ||

| COPD | 1.91 (1.43–2.56) | ||

| Liver disease | 1.07 (0.76–, 1.51) | ||

| AUC † | 0.70 (0.68–0.72) | 0.71 (0.69–0.73) | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) |

Number is the odds ratio for 5-point increase.

Numbers shown are the AUC and 95% confidence limits.

Numbers in bold have P-values <0.05. All models used ED visited and ED encounter month as cluster effects; Reference group for the outcome of all models is admission to general acute care.

AUC indicates area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ED, emergency department; OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to the body of research that has evaluated racial and ethnic differences in hospitalization for patients with COVID-19 by examining hospital admission for patients who sought care for COVID-19 in the ED. We found that, after controlling for demographic characteristics and comorbidities, Black patients who sought care for COVID-19 at one of RUSH’s EDs were significantly less likely to be admitted to the hospital than White or Hispanic patients. Black and Hispanic patients who sought care in the ED were younger, had fewer comorbidities, and lower RR than their White counterparts. These findings were somewhat surprising given that it is well documented that Blacks and Hispanics are more likely than Whites to be hospitalized for COVID-19.14

In Chicago and nationally, Black and Hispanic individuals had higher rates of infection from COVID-19 and were more likely to visit an ED for treatment for COVID-19. Using ED visit data from 13 states, the CDC found that Black and Hispanic individuals had significantly more COVID-19-related ED visits than White individuals in all age groups during October to December 2020, which may be attributed to long-standing systemic inequities that increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and may cause delayed care and increase the need for emergency care.15 Consistent with these findings, our study sample of COVID-19 patients seeking care in the ED was disproportionately Black and Hispanic (83.9%). Despite the fact that we had more Black and Hispanic ED patients in our sample, Black patients were less likely to be hospitalized from the ED. One possibility is that Black patients visited the ED with less severe cases of COVID than either White or Hispanic patients.

It is well-documented that Black individuals are more likely to visit the ED for nonurgent reasons and to rely on the ED for routine care compared to White individuals.16–19 A study examining ED use before COVID-19 using data from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey16 found that Black patients were more likely than White patients to visit the ED for nonemergent conditions whereas Hispanic patients were more likely than White patients to have emergent conditions. Black patients were less likely than White patients to be admitted to the hospital from the ED, whereas there was no difference in hospital admission or in ICU admission between Hispanic and White patients seen in the ED. ED use for COVID-related care may follow similar patterns. During the early months of the pandemic, many organizations switched to video visits and other telemediated care, which may have disproportionately limited access to primary care for Black and Hispanic patients, leaving care in the ED as the only option.

Another explanation for our finding that Black patients were less likely to be hospitalized may be unconscious bias on the part of health care providers in the ED. Extensive evidence indicates racial/ethnic disparities in treatment of patients in the ED.20,21 For example, in one study non-White patients presenting with abdominal pain were less likely to receive pain medication and less likely to be admitted.22 Overcrowding and high patient load in the ED has been associated with increases in implicit pro-White/anti-Black bias among ED physicians.23 Evidence suggests that ED length of stay was higher in 2020 due to COVID-19.24 The COVID-related stress on ED providers may have led to increased implicit racial bias, leading to lower rates of admission for Black patients.

We found no difference in the likelihood of hospital admission or ICU admission between Hispanic and White patients. Before COVID-19, studies comparing the odds of hospital admission between Hispanic and White patients have been mixed; 4 out of 10 studies found Hispanic patients had higher odds of admission than White patients25–28 and 6 found no difference.29–34 In addition, prior research has shown that Hispanic patients with lower levels of acculturation (ie, noncitizen immigrants, residing in the United States for <10 y) are less likely to seek care in the ED for nonurgent reasons.35 The lack of health insurance more than likely added to these barriers; in our sample more than 1-quarter of Hispanic patients were uninsured. We speculate that cultural, language, and insurance barriers deterred Hispanic patients with relatively mild COVID-19 symptoms from seeking care in the ED, resulting in Hispanic patients seeking diagnosis and care later in the course of the disease than Black patients, and as such, having equal likelihood of hospitalization as the White patients in our study.36

Strengths and Limitations

Our study is unique in that we focused on a sample of patients who sought care for COVID-19 within the ED. In contrast, most prior studies examined hospital admissions within the cohort of all positive COVID-19 cases tested within a hospital system. ED patients needing immediate hospitalization are likely to be hospitalized at the same hospital unless that hospital has no available beds or the patient needs a higher level of care. During the time period of this study, no ED patients at RUSH who needed immediate hospitalization were transferred to another acute care hospital. In studies using the cohort of all COVID-19 cases, patients who tested positive outside of a hospital, such as drive-through testing location or outpatient clinic, may be hospitalized elsewhere. Therefore, hospitalization rates that include patients who were tested at these outpatient locations may underestimate the proportion of cases that are subsequently hospitalized.

In addition, limiting our analysis to patients who sought care in the ED allowed us to include more detailed information about the patient’s comorbidities and clinical measures, such as Sp02 and RR that are not routinely collected at a COVID-19 testing site. This resulted in less missing data (missing sex for 1 patient) in our analysis relative to other studies examining hospitalization among all COVID-19 cases. For example, previous studies excluded patients with missing data for symptoms and comorbidities who were seen in an outpatient setting.37 Thus, by including all patients who were positive, the results might not take into account patients with unknown symptoms or comorbidity information. These patients may have had less severe infection, and thus not admitted.

While this study makes important contributions to understanding hospital admissions of COVID-19 patients by race and ethnicity, there are several limitations. First, information about comorbidities may be less complete for patients who are coming to this hospital system for the first time than for established patients. However, we attempted to mitigate this potential bias by only including diagnosis codes documented during the ED encounter. Also, a sensitivity analysis done on the subset of patients with a prior PCP visit or prior ED visit showed the same results as presented here.

Second, although encounter month was controlled for in the model, it may not have completely captured the effect of time on hospitalization rates across racial and ethnic groups. COVID-19 hospital protocols, hospital capacity, and city/state policies changed rapidly over time, as did the peaks and valleys of case rates by racial and ethnic groups in Chicago. Third, as is the case for other studies examining a single health care system, the results of this study are not necessarily generalizable to other healthcare systems.

This study provides a new lens on racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 hospitalization by examining hospitalization rates among patients seeking care for COVID-19 in the ED. This study found that after controlling for patient demographic and clinical characteristics, Black patients were less likely than White and Hispanic patients to be admitted to the hospital as well as less likely to be admitted to the ICU. Assuming that admission directly to the ICU is indicative of more severe clinical presentation in the ED than admission to a general acute care unit as suggested by the WHO’s definition of severity,38 our results suggest that Black patients may have presented to the ED with less severe cases of COVID-19 than White or Hispanic patients. Future work should examine whether the lack of alternative sources of care for less severe symptoms, such as virtual care and access to a PCP, are associated with seeking care in the ED for COVID-19 and the racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 hospital admission.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.

Footnotes

This study was funded by the Rush Coronavirus Research Fund.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Joshua Longcoy, Email: joshua_longcoy@rush.edu.

Rahul Patwari, Email: rahul_patwari@rush.edu.

Scott Hasler, Email: scott_g_hasler@rush.edu.

Tricia Johnson, Email: tricia_j_johnson@rush.edu.

Elizabeth Avery, Email: elizabeth_avery@rush.edu.

Kristina Stefanini, Email: kristina_n_stefanini@rush.edu.

Sumihiro Suzuki, Email: sumihiro_suzuki@rush.edu.

David Ansell, Email: david_ansell@rush.edu.

Elizabeth Lynch, Email: elizabeth_lynch@rush.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by State/Territory 2021. Available at: https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/covid-19/home/latest-data.html. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 2. Chicago Department of Public Health. Phase IV re-opening metrics and vax updates. 2021. Available at: https://www.chicago.gov/content/dam/city/sites/covid/reports/052721/COVID-Reopening-metrics-052121.pdf. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 3. Chicago Department of Public Health. Latest data. 2021. Available at: https://www.chicago.gov/city/en/sites/covid-19/home/latest-data.html. Accessed June 30, 2021.

- 4. Raharja A, Tamara A, Kok LT. Association between ethnicity and severe COVID-19 disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8:1563–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yancy CW. COVID-19 and African Americans. JAMA. 2020;323:1891–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldman JM, Bassett MT. The relationship between neighborhood poverty and COVID-19 mortality within racial/ethnic groups (Cook County, Illinois). MedRxiv. 2020;68:102540. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cummings MJ, Baldwin MR, Abrams D, et al. Epidemiology, clinical course, and outcomes of critically ill adults with COVID-19 in New York City: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1763–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang MH, Moonesinghe R, Truman BI. COVID-19 hospitalization by race and ethnicity: association with chronic conditions among Medicare Beneficiaries, January 1-September 30, 2020. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9:325–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thakur B, Dubey P, Benitez J, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of geographic differences in comorbidities and associated severity and mortality among individuals with COVID-19. Sci Rep. 2021;11:8562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KE, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19–related concerns—United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1250–1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Augustine JJ. Latest data reveal the ED’s role as hospital admission gatekeeper. ACEP Now, 40(12), 2021. Available at: https://www.acepnow.com/article/latest-data-reveal-the-eds-role-as-hospital-admission-gatekeeper/?singlepage=1. Accessed January 16, 2022.

- 12. Clinical Classifications Software Refined. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD; 2021. Available at: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccsr/ccs_refined.jsp. Accessed September 1, 2020.

- 13. Chatterjee NA, Jensen PN, Harris AW, et al. Admission respiratory status predicts mortality in COVID‐19. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2021;15:569–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mackey K, Ayers CK, Kondo KK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in COVID-19–related infections, hospitalizations, and deaths: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smith AR, DeVies J, Caruso E, et al. Emergency department visits for COVID-19 by race and ethnicity—13 states, October–December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:566–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang X, Carabello M, Hill T, et al. Trends of racial/ethnic differences in emergency department care outcomes among adults in the United States from 2005 to 2016. Front Med. 2020;7:300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cairns C, Ashman JJ, Kang K. Emergency department visit rates by selected characteristics: United States, 2018. NCHS Data Brief. 2021;401:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Johnson PJ, Ghildayal N, Ward AC, et al. Disparities in potentially avoidable emergency department (ED) care: ED visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Med Care. 2012;50:1020–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Glover CM, Purim-Shem-Tov YA. Emergency department utilization: a qualitative analysis of Illinois Medical Home Network Patients. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2016;9:10. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pezzin LE, Keyl PM, Green GB. Disparities in the emergency department evaluation of chest pain patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Musey PI, Jr, Studnek JR, Garvey L. Characteristics of ST elevation myocardial infarction patients who do not undergo percutaneous coronary intervention after prehospital cardiac catheterization laboratory activation. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2016;15:16–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shah AA, Zogg CK, Zafar SN, et al. Analgesic access for acute abdominal pain in the emergency department among racial/ethnic minority patients: a nationwide examination. Med Care. 2015;53:1000–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Johnson TJ, Hickey RW, Switzer GE, et al. The impact of cognitive stressors in the emergency department on physician implicit racial bias. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lucero A, Sokol K, Hyun J, et al. Worsening of emergency department length of stay during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Am Coll Emerg Phys Open. 2021;2:e12489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lundon DJ, Mohamed N, Lantz A, et al. Social determinants predict outcomes in data from a multi-ethnic cohort of 20,899 patients investigated for COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:571364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dai CL, Kornilov SA, Roper RT, et al. Characteristics and factors associated with COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality across race and ethnicity. MedRxiv. 2021;73:2193–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cardemil CV, Dahl R, Prill MM, et al. COVID-19-related hospitalization rates and severe outcomes among Veterans from 5 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers: hospital-based surveillance study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7:e24502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gershengorn H, Patel S, Shukla B, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with COVID-19 test positivity and hospitalization is mediated by socioeconomic factors. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:1326–1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, et al. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39:1253–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cromer SJ, Lakhani CM, Wexler DJ, et al. Geospatial analysis of individual and community-level socioeconomic factors impacting SARS-CoV-2 prevalence and outcomes. MedRxiv. 2020. [Epub ahead of print]. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Golestaneh L, Neugarten J, Fisher M, et al. The association of race and COVID-19 mortality. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;25:100455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ioannou GN, Locke E, Green P, et al. Risk factors for hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, or death among 10131 US Veterans with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2022310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ogedegbe G, Ravenell J, Adhikari S, et al. Assessment of racial/ethnic disparities in hospitalization and mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York City. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2026881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Renelus BD, Khoury NC, Chandrasekaran K, et al. Racial disparities in COVID-19 hospitalization and in-hospital mortality at the height of the New York City pandemic. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;8:1161–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Allen L, Cummings J. Emergency department use among Hispanic adults: the role of acculturation. Med Care. 2016;54:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Khanijahani A, Iezadi S, Gholipour K, et al. A systematic review of racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in COVID-19. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gottlieb M, Sansom S, Frankenberger C, et al. Clinical course and factors associated with hospitalization and critical illness among COVID-19 patients in Chicago, Illinois. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27:963–973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization. WHO R&D Blueprint: novel coronavirus COVID-19 therapeutic trial synopsis. 2020. Available at: http://www.who.int/blueprint/priority-diseases/key-action/COVID-19_Treatment_Trial_Design_Master_Protocol_synopsis_Final_18022020.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Digital Content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's website, www.lww-medicalcare.com.