Abstract

Forty rhizobia nodulating four Acacia species (A. gummifera, A. raddiana, A. cyanophylla, and A. horrida) were isolated from different sites in Morocco. These rhizobia were compared by analyzing both the 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) and the 16S-23S rRNA spacer by PCR with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis. Analysis of the length of 16S-23S spacer showed a considerable diversity within these microsymbionts, but RFLP analysis of the amplified spacer revealed no additional heterogeneity. Three clusters were identified when 16S rDNA analysis was carried out. Two of these clusters include some isolates which nodulate, nonspecifically, the four Acacia species. These clusters, A and B, fit within the Sinorhizobium lineage and are closely related to S. meliloti and S. fredii, respectively. The third cluster appeared to belong to the Agrobacterium-Rhizobium galegae phylum and is more closely related to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens species. These relations were confirmed by sequencing a representative strain from each cluster.

Acacia is a legume tree which fixes nitrogen through a symbiosis with rhizobia. In Morocco, A. raddiana and A. gummifera (native species) are found in arid and Saharan areas. These acacias are generally very sparse and overused by local people, who have no other fuelwood. Regeneration of the trees is made difficult owing to overgrazing, which adds its limiting effects to those of aridity. Therefore, there is a crucial need to rehabilitate these natural populations in order to halt desert encroachment and to restore soil fertility. One possible approach to improve rehabilitation programs is to isolate rhizobia from these areas and obtain data on their diversity and nodulation spectrum.

In the last few years, many studies have investigated rhizobia associated with legume trees (8, 24, 52) and various techniques have been used to identify and describe strains. These studies concluded that there is a large heterogeneity among the strains, and, accordingly, they were often divided into several groups (2, 6, 8, 9, 15, 27, 52). The low similarity among these groups shows that trees can form nodules and fix nitrogen with several different clusters of rhizobia (6, 15, 23, 33).

In eubacteria, rRNA genetic loci include 16S, 23S and 5S genes, which are separated by two internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions. DNA sequences in the 16S-23S spacer are known to exhibit a great deal of sequence and length variation (17). These variations are used to differentiate genera, species, and strains of prokaryotes (4, 12–14, 26) especially in the alpha division of the proteobacteria (32). In contrast and with a few exceptions only, the rRNA genes (rDNAs) are similar in length throughout the bacterial kingdom and contain highly conserved regions as well as regions that vary according to species and family (48). Consequently, sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, which is the most extensively studied, is a well-established standard method for phylogenetic (50) and taxonomic (1, 48) studies. These 16S rDNA sequence analyses support the well-established subdivision of rhizobia into species and genera (47, 49, 50). A rapid and versatile method based on restriction endonuclease site differences in PCR-amplified 16S rDNA has been used as an alternative to sequencing (35, 36). In rhizobia, species assignments based on PCR with restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis of the 16S rRNA gene were consistent with the established taxonomic classification (20).

Our objective was to determine the genetic diversity among rhizobia isolated from different soils and tested on four Acacia species and to find their phylogenetic positions within the family Rhizobiaceae by using 16S rRNA analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

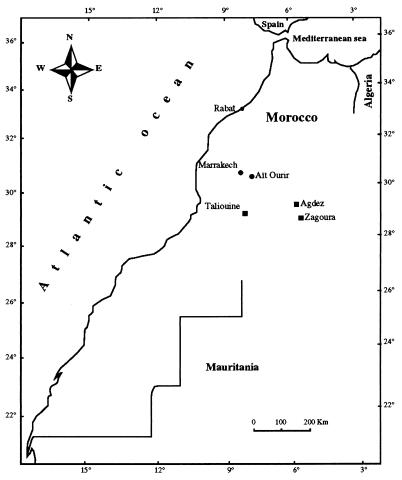

Strains of rhizobia were isolated from root nodules harvested from young seedlings of four Acacia species (A. horrida, A. gummifera, A. raddiana, and A. cyanophylla) inoculated with 1 ml of a soil suspension. These soil samples had been collected in various regions of Morocco (Fig. 1) and were screened for the presence of rhizobia as described by De Lajudie et al. (8).

FIG. 1.

Locations of soil sampling in Morocco. Symbols: •, Acacia gummifera; ■, Acacia raddiana.

All strains of rhizobia used in this study are listed in Table 1. Type or representative strains of rhizobia and agrobacteria were obtained from the Collection des Souches de l’ORSTOM, Dakar, Senegal.

TABLE 1.

Rhizobia used in this study

| Geographic origin and climate | Isolatea | Host rangeb | ITS group (PCR with RFLP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aït Ourir, arid | MSMC14 | A. cyanophylla | 1 |

| MSMC413 | A. raddiana, A. horrida | 1 | |

| MSMC418 | ND | 1 | |

| Zagora, Saharan | MSMC37 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 |

| MSMC38 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC311 | A. gummifera, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC313 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC414 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC26 | — | 6 | |

| MSMC211 | — | 6 | |

| MSMC45 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC46 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC47 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC49 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC419 | ND | 1 | |

| MSMC28 | A. raddiana, A. gummifera, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 3 | |

| MSMC21 | A. cyanophylla | 4 | |

| MSMC25 | — | 4 | |

| MSMC31 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 5 | |

| MSMC32 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 5 | |

| MSMC210 | — | 7 | |

| Agdez, arid | MSMC411 | A. raddiana, A. cyanophylla | 2 |

| Taliouine, arid | MSMC111 | A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 |

| MSMC112 | A. horrida | 1 | |

| MSMC114 | A. raddiana, A. horrida | 1 | |

| MSMC115 | A. raddiana, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC310 | A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC48 | ND | 1 | |

| MSMC29 | ND | 3 | |

| MSMC116 | A. raddiana | 8 | |

| MSMC24 | – | 9 | |

| MSMC33 | – | 10 | |

| Marrakech, arid | MSMC312 | A. horrida | 1 |

| MSMC314 | A. raddiana, A. gummifera, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 1 | |

| MSMC315 | A. raddiana, A. horrida | 1 | |

| MSMC11 | A. raddiana, A. cyanophylla | 2 | |

| MSMC12 | A. raddiana, A. gummifera, A. cyanophylla | 2 | |

| MSMC412 | A. raddiana, A. horrida, A. cyanophylla | 2 | |

| MSMC416 | ND | 2 | |

| MSMC417 | ND | 2 |

MSMC, Moroccan Symbiotic Microorganisms Collection.

—, no nodulation; ND, not determined.

All the rhizobia were maintained on yeast extract mannitol medium (46).

Plant infection tests.

The Rhizobium strains were tested for the ability to nodulate A. horrida, A. gummifera, A. raddiana, and A. cyanophylla. The Acacia seeds were surface sterilized in 1% (wt/vol) calcium hypochlorite for 10 min, rinsed with sterile water, and then scarified. The seeds were germinated for 72 h on 0.7% (wt/vol) agar medium in a growth chamber at 28°C, and the seedlings were placed aseptically in Gibson tubes (12) supplemented with a nitrogen-free plant nutrient solution (3). Each tube was inoculated with a rhizobial suspension from an early-stationary-phase culture. Uninoculated plants and plants to which nitrogen (10 mM KNO3) was added were used as controls. Three replicates were prepared for each treatment. After 50 days, the plants were harvested and the number of nodules was counted.

DNA extraction.

Stationary-phase Tp broth cultures (1.5 ml each) were centrifuged, and the cells were resuspended in sterile distilled water, boiled for 10 min, and immediately cooled on ice to induce lysis. Tp medium contained (per liter of distilled water) 4 g of Bacto Peptone (Difco), 0.5 g of Bacto Tryptone (Difco), 0.5 g of yeast extract (Difco), 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.2 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O.

16S-23S spacer amplification.

The intergenic region between the 16S and 23S rDNAs was amplified by PCR with primers derived from the 3′ end of the 16S rDNA (FGPS1490-72; 5′-TGCGGCTGGATCCCCTCCTT-3′) (28) and from the 5′ end of the 23S rDNA (FGPL132′-38; 5′-CCGGGTTTCCCCATTCGG-3′) (35). PCR amplification was performed with a Perkin-Elmer Cetus model 2400 thermocycler. Each reaction mixture contained 5 μl of lysed cell suspension, 1× reaction buffer (Gibco BRL, Cergy-Pontoise, France), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 20 μM (each) dATP, dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP (Pharmacia-LKB), primers at 0.1 μM each, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL). The PCR temperature profile used was 94°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles consisting of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension step at 72°C for 3 min. Reaction efficiency was estimated by electrophoresis of 5 μl of the amplification product on a 0.8% (wt/vol) horizontal agarose gel. After migration, the gels were stained in an aqueous solution of ethidium bromide (1 mg/ml) and photographed under UV illumination with Ilford HP5 films.

16S rRNA gene amplification.

The conditions for 16S gene amplification were the same as those used for 16S-23S spacer amplification, except that the annealing steps took place at 60°C and the extension periods were 2 min in each cycle. The prokaryotic specific primers used for 16S rRNA gene amplification were FGPS4-281bis (5′-ATGGAGAAGTCTTGATCCTGGCTCA-3′) and FGPS1509′-153 (5′-AAGGAGGGGATCCAGCCGCA-3′) (31).

Restriction fragment analysis.

Aliquots (8 μl) of PCR products were digested with restriction endonucleases (Boehringer Mannheim, Meylan, France) as specified by the manufacturer but with an excess of enzyme (5 U per reaction) in a total volume of 10 μl. The following enzymes were used: AluI, DdeI, CfoI, HhaI, HinfI, HpaI, RsaI, Sau3A, and TaqI. The restriction fragments were separated by horizontal electrophoresis in TBE buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) with a 2% (wt/vol) MetaPhor (FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine) agarose gel containing 1 μg of ethidium bromide per ml. The gels were run at 80 V for 3 h and immediately photographed with Ilford HP5 films with a 320-nm UV source.

16S rRNA gene sequencing.

The 16S rRNA gene of strains MSMC 211, MSMC 310, and MSMC 411 was amplified. The amplified fragments were purified with the QIAEX II kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.) and sequenced by the dideoxy chain termination method of Sanger et al. (39). The six primers used for sequencing the whole of the 16S rRNA gene were FGPS4-281bis (5′-ATGGAGAAGTCTTGATCCTGGCTC-3′), FGPS485-292 (5′-CAGCAGCCGCGGTAA-3′), FGPS1047-295 (5′-ATGTTGGGTTAAGTC-3′), FGPS505′-313 (5′-GTATTACCGCGGCTGCTG-3′), FGPS910′-270 (5′-AGCCTTGCGGCCGTACTCCC-3′), and FGPS1509′-153 (5′-AAGGAGGGGATCCAGCCGCA-3′) (31).

DNA sequence analysis.

The 16S rDNA sequences were aligned and analyzed with the sequence editor Phylo-Win (11). Phylogenetic analysis was inferred by using the neighbor-joining method (38) calculated by the Kimura (18) and parsimony (19) methods. A bootstrap confidence analysis was performed with 1,000 replicates (10). The resulting tree was drawn with the NJplot software of Perrière and Gouy (34). The 16S rRNA sequences of the following organisms belonging to the Rhizobiaceae were used for comparison (GenBank accession numbers are in parentheses): R. leguminosarum ATCC 14482 (U29386), R. etli CFN 42 (U28916), R. tropici type IIa CFN 299 (X67234), R. tropici type IIb CIAT 899T (X67233), Mesorhizobium ciceri UPM-Ca7T (U07934), M. huakuii IAM 14158T (D13431), M. loti NZP 2213T (X67229), M. mediteraneum UPM-Ca36T (L38825), Mesorhizobium sp. strain (group Ua) ORS 1001 (X68389), Sinorhizobium fredii USDA 205T (X67231), S. medicae A321T (L39882), S. meliloti NZP 4027T (X67222), S. saheli ORS 609T (X68390), S. teranga ORS 1009T (X68388), R. galegae HAMBI 540T (D11343), Agrobacterium tumefaciens LMG 187 (D14500), A. rhizogenes ATCC 11325 (D14501), A. rubi LMG 156 (X67228), A. vitis NCPPB 2611 (U45329), Agrobacterium sp. strain LMG 230 (D14506), Agrobacterium sp. strain LMG 196 (X67223), Agrobacterium sp. strain 3-10 (Z30542), Bradyrhizobium elkanii USDA 76 (U35000), B. japonicum USDA 110 (D13430), and Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS 571T (D11342).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The newly determined 16S rRNA sequences were deposited in the EMBL Data Library under accession no. AJ004859 to AJ004861.

RESULTS

Plant infection tests.

We tested 34 strains of rhizobia on four Acacia species (Table 1). A. raddiana, A. cyanophylla, and A. horrida appeared to belong to the same group of host plant, since the majority of the strains tested could induce root nodules on them besides their original host. Only a few strains (less than 15% of the total) could induce a few nodules on A. gummifera, indicating that this plant probably requires special growth conditions for nodulation. Some strains (about 17%) did not nodulate any of these plants, even their original host.

16S-23S rDNA spacer analysis.

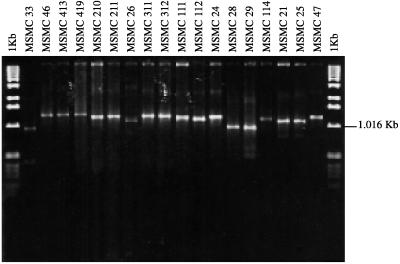

To further investigate the genetic differences among the 40 rhizobia isolated from Acacia species in arid and Saharan areas of Morocco, we analyzed the 16S-23S rDNA spacer by PCR with RFLP analysis. Electrophoresis of nondigested PCR products revealed that each isolate possesses one band (Fig. 2). The length of the ITS amplified region, which included about 200 bp of the 16S and 23S genes, was not the same for all strains tested (it was between 1 and 1.4 kb). Therefore, we were able to identify 10 groups corresponding to 10 different bands in this natural population of rhizobia (Table 1). Group 1 contains the majority (22 of 40) of the isolates, which are characterized by an ITS of 1.3 kb. Group 2 contains six isolates, which have an ITS slightly longer than 1.3 kb. The two group 3 isolates have an ITS of 1.2 kb. The two group 4 isolates have an ITS of slightly more than 1.1 kb. The two group 5 isolates have an ITS of 1.1 kb. The two group 6 isolates have an ITS slightly longer than 1.0 kb. Group 7, a heterogeneous group, contains four isolates which each showed a specific length of ITS.

FIG. 2.

Electrophoresis of PCR products obtained with the universal primers FGPS1490-72 and FGPL132′-38, which target the ribosomal ITS of Rhizobium strains that nodulate Acacia spp.

PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes.

The 16S rDNAs of 20 strains, which represent the seven groups identified above, were amplified, as well as those of type strains belonging to different rhizobia and agrobacteria. The stringency conditions of PCR allowed the amplification of a single band of about 1,500 bp for all the strains tested except R. tropici type IIa strain CFN 299, which possesses an insertion of 72 nucleotides (46), yielding a single band of about 1,600 bp (data not shown).

RFLP analysis of amplified 16S rRNA genes.

The PCR product derived from each strain was digested separately by nine 4-base-cutting enzymes, and the resulting fragments were separated by electrophoresis (data not shown). The length of PCR product estimated by summing the sizes of the restricted fragments was shorter than or equal to 1,500 or 1,600 bp for CFN 299. Between 4 and 13 distinct restriction patterns were detected with each of the nine endonucleases in the strains tested in this study. All the patterns of reference strains were confirmed by computer-simulated RFLP analysis of their 16S rDNA published sequences (30).

A total of 20 different combinations, each corresponding to one genotype, were identified among the 44 strains analyzed by RFLP in this study. Only three genotypes were distinguished when the 16S rDNA polymorphism was analyzed for the unclassified rhizobia nodulating Acacia spp. in Morocco. The patterns of these three genotypes were compared with those of strains belonging to recognized species. One group (group A) showed restriction profiles closer to those of S. meliloti. This group includes strains which are clustered in all the different ITS groups except group 1. The second group (group B) comprises strains which belonged to group 1 and showed restriction patterns identical to those of S. fredii. The third group (group C) contains three strains, which cannot renodulate any of the four Acacia species after their first isolation. This group is different from A. tumefaciens B6 by only the NdeII and MspI restriction patterns.

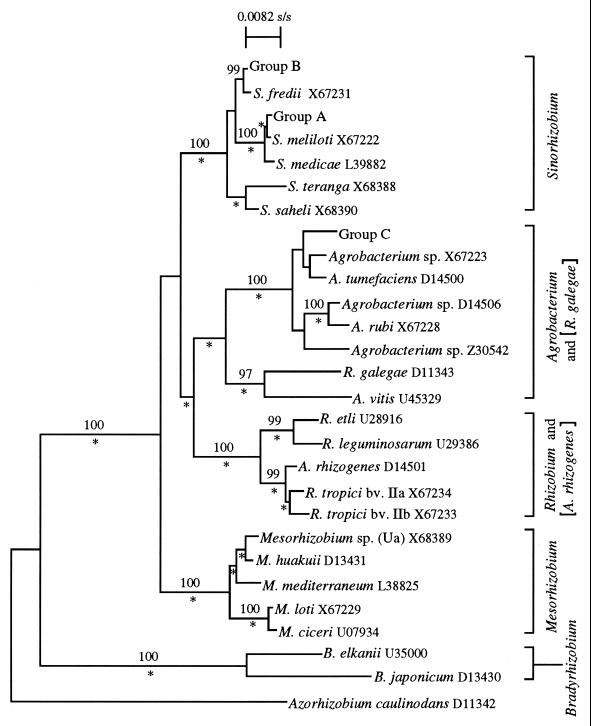

16S rDNA sequence analysis.

The 16S rDNA sequences of the following strains representing the three identified Rhizobium genotypes were determined: MSMC 411 from group A, MSMC 310 from group B, and MSMC 211 from group C (data not shown). These sequences were aligned and compared with the 16S rDNA sequences of other members of the family Rhizobiaceae available in the GenBank database. Figure 3 is a dendrogram which shows the phylogenetic relationships of these unclassified rhizobia and the previously named species of Rhizobiaceae. MSMC 411 and MSMC 310, and their respective groups, are included in the Sinorhizobium lineage and exhibit a high level of relatedness to S. meliloti (99.7% sequence similarity, corresponding to three nucleotide substitutions and one deletion for a comparison of 1,440 bases) and S. fredii (99.8% sequence similarity, corresponding to three nucleotide substitutions for a comparison of 1,440 bases), respectively. In contrast, strain MSMC 211, which represents group C, fell in the Agrobacterium-R. galegae lineage and is most closely related to A. tumefaciens (98.9% sequence similarity, corresponding to 15 nucleotide substitutions for a comparison of 1,440 bases).

FIG. 3.

Neighbor-joining tree of Rhizobium isolate 16S rRNA genes and phyletic neighbors. The GenBank accession numbers are given after the species names. Bootstrap results higher than 95% are given above the node. The asterisks below the nodes indicate those also found by parsimony analysis.

DISCUSSION

We decided to make a collection and database of rhizobia that nodulate acacias. Zerhari et al. (51) have isolated more than 50 isolates from seedlings of four Acacia species and established their infective potential as well as their host range and their phenotypic diversity.

We have used PCR with RFLP analysis to analyze 16S-23S spacer variation among these rhizobia. The ITS between the 16S and 23S rRNA genes may be an effective marker for detecting genetic differences at the intergeneric level and also at the interspecific level. These differences are partly due to variations in the number and type of tRNA genes found in these spacers (17).

We found great diversity in the length of the amplification bands among the rhizobium strains. Therefore, we were able to distinguish 10 groups on the basis of ITS length. Classification of rhizobium strains to any of these ITS groups appeared to be independent of the host plant and site of origin. The high level of ITS size heterogeneity is consistent with the results of Zerhari et al. (51) in an extensive study of 52 phenotypic characteristics, indicating that these rhizobia seem to belong to several different clusters. Such length variability of the 16S-23S spacer was also recorded by Laguerre et al. (22) between genotypes distantly or closely related within R. leguminosarum. However, digestion of the amplified 16S-23S spacer with nine restriction enzymes did not allow us to make a clearer distinction among the strains. A similar result was also found by Neyra (29) when investigating several strains belonging to Sinorhizobium saheli or S. terranga by using PCR with RFLP. The lack of differences in the restriction patterns obtained with the nine enzymes used suggests that there is little sequence variability in the ITS among tree-nodulating rhizobia that cannot be revealed by RFLP analysis.

We decided to determine the phylogenetic relationships of these natural rhizobia through 16S rDNA sequence analysis. We first used the PCR method with RFLP to categorize 20 rhizobia nodulating Acacia spp. in Morocco and type strains of members of the Rhizobiaceae. The results of this study for the type species of the Rhizobiaceae were consistent with the taxonomic classification based on DNA-DNA homology (5, 6, 8, 16, 23, 26, 40–42) or, for R. tropici, R. etli, and S. medicae, on sequence analysis of the 16S rDNA segment (26, 37, 43). The variations observed between 16S rDNA sequences within the strains studied were sufficient to distinguish between all of them but two. The two type strains of R. tropici type IIb and A. rhizogenes yielded the same profiles with all enzymes tested. This had also been found by Laguerre et al. (21) and predicted by Willems and Collins (47) from sequence data of strain CFN 299.

Three groups, A, B, and C, were identified among unclassified rhizobia isolated from Acacia spp. in Morocco and examined in this study. Groups A and B are more closely related to Sinorhizobium species (S. meliloti and S. fredii, respectively). This result was predicted by De Lajudie (7) when investigating some of our strains by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. To our knowledge, there are many data showing that a high proportion of tree-nodulating rhizobia are more closely related to Sinorhizobium species (8, 24, 45).

In contrast, group C belongs to the Agrobacterium-R. galegae lineage and is more closely related to A. tumefaciens. This group includes three isolates, each showing a specific 16S-23S spacer and unable to renodulate any of the four Acacia species. In a further investigation, no PCR amplification could be observed with specific primers for a conserved region in the nodD gene, thus suggesting that these strains do not carry nod genes.

Two hypotheses concerning the presence in nodules of these rhizobia resembling Agrobacterium can be advanced. First, these strains lacking all or part of their symbiotic information could penetrate together with other infective rhizobia and coexist with them. In fact, nonsymbiotic Rhizobium strains lacking symbiotic information have been found in soils (21, 42, 44). Alternatively, these strains could originally be infective, penetrate into the nodule, and subsequently lose their symbiotic information, or at least their nod genes, during symbiosis or after isolation and cultivation on agar plates, as was found by Macheret (25) for R. leguminosarum bv. phaseoli.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partly supported by the Bureau des ressources génétiques (Paris, France) and two UNESCO fellowships.

We thank Joëlle Marechal and Jaqueline Haurat for their valuable technical assistance. We also thank Xavier Nesme, Benoit Cournoyer, and Jean-Christophe Thoma (Université Claude Bernard, Lyon 1, France) for helpful discussions. We thank Salah Mohammed Hassan (Université Mohammed V, Rabat, Morocco) and Albert Sasson (UNESCO, Paris, France) for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batzli J M C, Graves W R, Berkum P V. Diversity among rhizobia effective with Robinia pseudoacacia L. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2137–2143. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.7.2137-2143.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunel B, Rome S, Ziani R, Cleyet-Marel J C. Comparison of nucleotide diversity and symbiotic properties of Rhizobium meliloti populations from annual species of Medicago. FEMS Microbiol Ecol Lett. 1996;19:71–82. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cartwright C P, Stock F, Beekmann S E, Williams E C, Gill V J. PCR amplification of rRNA intergenic spacer regions as a method for epidemiologic typing of Clostridium difficile. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:184–187. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.184-187.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W X, Li G S, Qi Y L, Wang E T, Yuan H L, Li J L. Rhizobium huakuii sp. nov. isolated from the root nodules of Astragalus sinicus. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:275–280. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crow V L, Jarvis B D W, Greenwood R M. Deoxyribonucleic acid homologies among acid-producing strains of Rhizobium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1981;31:152–172. [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Lajudie, P. Unpublished data.

- 8.De Lajudie P, Willems A, Pot B, Dewettinck D, Maestrojuan G, Neyra M, Collins M D, Dreyfus B, Kersters K, Gillis M. Polyphasic taxonomy of rhizobia: emendation of the genus Sinorhizobium and description of Sinorhizobium meliloti comb. nov., Sinorhizobium saheli sp. nov., and Sinorhizobium teranga sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:715–733. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupuy N, Willems A, Pot B, Dewettinck D, Vandenbruaene I, Maestrojuan G, Dreyfus B, Kersters K, Collins M D, Gillis M. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bradyrhizobia nodulating the leguminous tree Acacia albida. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:461–473. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galtier N, Gouy M, Gautier C. SeaView and Phylo-Win, two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gibson A H. Methods for legumes in glasshouse and controlled environment cabinets. In: Bergersen F J, editor. Methods for evaluating biological nitrogen fixation. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1980. pp. 139–184. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurtler V. Typing Clostridium difficile strains by PCR-amplification of variable length 16S-23S rDNA spacer regions. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:3089–3097. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-12-3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurtler V, Stanisich V A. New approaches to typing and identification of bacteria using the 16S-23S rDNA spacer region. Microbiology. 1996;142:3–16. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarvis B D W. Genetic diversity of Rhizobium strains which nodulate Leucaena leucocephala. Curr Microbiol. 1983;8:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jarvis B D W, Pankhurst C E, Patel J J. Rhizobium loti, a new species of legume root nodule bacteria. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1982;32:378–380. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen M A, Webster J A, Straus N. Rapid identification of the bacteria on the basis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified ribosomal DNA spacer polymorphisms. App Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:945–952. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.945-952.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kluge A G, Farris J S. Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anurans. Syst Zool. 1969;18:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laguerre G, Allard M-R, Revoy F, Amarger N. Rapid identification of rhizobia by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:56–63. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.1.56-63.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laguerre G, Bardin M, Amarger N. Isolation from soil of symbiotic and nonsymbiotic Rhizobium leguminosarum by DNA hybridization. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:1142–1149. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laguerre G, Mavingui P, Allard M-R, Charnay M-P, Louvrier P, Mazurier S-I, Rigottier-Gois L, Amarger N. Typing of rhizobia by PCR DNA fingerprinting and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of chromosomal and symbiotic gene regions: application to Rhizobium leguminosarum and its different biovars. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:2029–2036. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.2029-2036.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindström K, Lehtomäki S. Metabolic properties, maximum growth temperature and phage sensitivity of Rhizobium sp. (Galega) compared with other fast-growing rhizobia. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;50:277–287. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindström K, Jarvis B D W, Lindström P E, Patel J J. DNA homology, phage typing and cross-nodulation studies of rhizobia infecting Galega species. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29:781–789. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macheret V. Mise au point de sondes ADN pour la detection et la caractérisation des Rhizobium: application à l’isolement à partir du sol des Rhizobium symbiotes du haricot. Thèse de Doctorat. Bourgogne, France: Université de Bourgogne; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Romero E, Segovia L, Mercante F M, Franco A A, Graham P, Pardo M A. Rhizobium tropici, a novel species nodulating Phaseolus vulgaris L. beans and Leucaena sp. trees. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:417–426. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-3-417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moreira F, Gillis M, Pot B, Kersters K, Franco A A. Characterization of rhizobia isolated from different divergence groups of tropical Leguminoseae by comparative polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of their total proteins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;16:135. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navarro E, Simonet P, Normand P, Bardin R. Characterization of natural populations of Nitrobacter spp. using PCR/RFLP analysis of the ribosomal intergenic spacer. Arch Micrbiol. 1992;157:107–115. doi: 10.1007/BF00245277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neyra, M. Unpublished data.

- 30.Neyra, M., B. Khbaya, P. De Lajudie, B. Dreyfus, and P. Normand. Computer assisted selection of restriction enzyme for rrs genes PCR/RFLP descrimination of rhizobial species. Genome Select. Evol., in press.

- 31.Normand P. Utilisation des séquences 16S pour le positionnement phylétique d’un organisme inconnu. Océanis. 1995;21:31–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Normand P, Ponsonnet C, Nesme X, Neyra M, Simmonet P. Molecular microbiology ecology manual. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1996. ITS analysis of prokaryotes; pp. 3.4.5. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Padmanabhan S, Hirtz R D, Broughton W J. Rhizobia in tropical legumes: cultural characteristics of Bradyrhizobium and Rhizobium sp. Soil Biol Biochem. 1990;22:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perrière G, Gouy M. WWW-Query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ponsonnet C, Nesme X. Identification of Agrobacterium strains by PCR-RFLP analysis of pTi and chromosomal regions. Arch Microbiol. 1994;16:300–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00303584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ralph D, McClelland M, Welsh J, Baranton G, Perolat P. Leptospira species categorized by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and by mapped restriction polymorphisms in PCR-amplified rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:973–981. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.973-981.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rom S, Fernandez M P, Brunel B, Normand P, Cleyet-Marel J-C. Sinorhizobium medicae sp. nov., isolated from annual Medicago spp. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:972–980. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scholla M H, Elkan G H. Rhizobium fredii sp. nov., a fast-growing species that effectively nodulates soybean. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1984;34:484–486. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scholla M H, Moorefield J A, Elkan G H. DNA homology between species of the rhizobia. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:288–294. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Segovia L, Pinero D, Palacios R, Martinez-Romero E. Genetic structure of a soil population of nonsymbiotic Rhizobium leguminosarum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:426–433. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.2.426-433.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Segovia L, Young J P-W, Martinez-Romero E. Reclassification of American Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar. phaseoli type I strains as Rhizobium etli sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:374–377. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soberon-Chavez G, Najera R. Isolation from soil of Rhizobium leguminosarum lacking symbiotic information. Can J Microbiol. 1989;35:464–468. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trinick M J. Relationships among fast-growing rhizobia of Lablab purpureus, Leucaena leucocephala, Mimosa spp., Acacia farnesiana and Sesbania grandiflora and their affinities with other rhizobia groups. J Appl Bacteriol. 1980;49:39–53. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vincent J M. A manual for the practical study of root nodule bacteria. IBP handbook, no. 15. Oxford, England: Blackwell Scientific Publications, Ltd.; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willems A, Collins M D. Phylogenetic analysis of rhizobia and agrobacteria based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:305–313. doi: 10.1099/00207713-43-2-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yanagi M, Yamasato K. Phylogenetic analysis of the family Rhizobiaceae and related bacteria by sequencing of 16S rRNA gene using PCR and DNA sequencer. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;107:115–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young J P W, Downer H L, Eardly B D. Phylogeny of the phototrophic Rhizobium strain BTAil by polymerase chain reaction-based sequencing of a 16S rRNA gene segment. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2271–2277. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.7.2271-2277.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zerhari K, Aurag J, Filali-Maltouf A. Biodiversity of Rhizobium sp. strains isolated from Acacia spp. species in south of Morocco. In: Elmerich C, et al., editors. Biological nitrogen fixation for the 21st century. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang X, Harper R, Karsisto M, Lindström K. Diversity of Rhizobium bacteria isolated from the root nodules of leguminous trees. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1991;41:104–113. [Google Scholar]