Abstract

Microbial rhizopine-catabolizing (Moc) activity was detected in serial dilutions of soil and rhizosphere washes. The activity observed generally ranged between 106 and 107 catabolic units per g, and the numbers of nonspecific culture-forming units were found to be approximately 10 times higher. A diverse set of 37 isolates was obtained by enrichment on scyllo-inosamine-containing media. However, none of the bacteria that were isolated were found to contain DNA sequences homologous to the known mocA, mocB, and mocC genes of Sinorhizobium meliloti L5-30. Twenty-one of the isolates could utilize an SI preparation as the sole carbon and nitrogen source for growth. Partial sequencing of 16S ribosomal DNAs (rDNAs) amplified from these strains indicated that five distinct bacterial genera (Arthrobacter, Sinorhizobium, Pseudomonas, Aeromonas, and Alcaligenes) were represented in this set. Only 6 of these 21 isolates could catabolize 3-O-methyl-scyllo-inosamine under standard assay conditions. Two of these, strains D1 and R3, were found to have 16S rDNA sequences very similar to those of Sinorhizobium meliloti. However, these strains are not symbiotically effective on Medicago sativa, and DNA sequences homologous to the nodB and nodC genes were not detected in strains D1 and R3 by Southern hybridization analysis.

Rhizopines are inositol derivatives synthesized in legume nodules induced by specific members of the Rhizobiaceae (14, 31). The first rhizopine was isolated from alfalfa nodules infected with Sinorhizobium meliloti L5-30 (28). The structure of this compound was determined to be 3-O-methyl-scyllo-inosamine (MSI) (13). Genes on the large symbiotic plasmid of strain L5-30 were determined to be involved in the synthesis and catabolism of this compound (12). Transposon mutagenesis and subsequent DNA sequence analysis of the rhizopine catabolism (moc) locus from this strain revealed the presence of four open reading frames (ORFs) involved in the catabolism of MSI (24). Three of these ORFs, mocA, mocB, and mocC, have been found to be sufficient to confer microbial rhizopine-catabolizing (Moc) activity onto otherwise Moc− strains of S. meliloti (25). DNA sequences homologous to these moc genes were not observed in a broad screen of known soil and rhizosphere bacteria (24), and only members of the Rhizobiaceae have been reported to be Moc+ (14).

Some organic molecules may be used to specifically promote the growth and metabolic activities of soil and rhizosphere bacteria capable of utilizing them as growth substrates (5, 6, 13, 18, 23–25). Several recent reports have shown that these specific nutritional mediators can enrich for bacteria capable of utilizing them as growth substrates in soil and on plant leaves and roots (3, 4, 7, 10, 20, 27, 29, 33–35). However, the potential of nutritional mediators to promote the activities of target microbial populations may be limited by a variety of factors, including the relative abundance of nontarget microbes capable of catabolizing the compound. While several reports have indicated that other proposed nutritional mediators can be catabolized by a variety of indigenous bacteria (5, 15, 16, 19), no previous study has directly investigated rhizopine catabolism in the environment. Here we report the detection, isolation, and enumeration of previously unknown rhizopine-catabolizing bacteria from the environment and discuss the implications of their existence for the use of rhizopine as a selective nutritional mediator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil and rhizosphere sampling.

Samples of a Michigan sandy loam were obtained from a followed plot on the Michigan State University Crop and Soil Sciences Research Farm, East Lansing. The plot had been left fallow for 5 years prior to these experiments and was covered by a variety of annual and perennial plants, including nodulated alfalfa. In September of 1995, approximately 50 kg was removed from the top 12 in. of the soil and transported to a research greenhouse for mixing and storage. Rocks and wooden debris were removed as the soil was homogenized in a rotary mixer. This soil was allowed to air dry and was stored at room temperature until use.

For the initial detection and quantification of rhizopine catabolic activities, aliquots of this soil were placed in plastic pots, moistened, planted with Medicago sativa var. Cardinal, and incubated in a growth chamber (12 h in the light, 12 h in the dark, 22°C). Soil and rhizosphere samples (<100 mg each) were taken after 1 and 3 weeks of incubation. Samples were placed in 5 ml of distilled water in 15-ml Sarstedt tubes. Bacteria were dislodged by alternating 10-s treatments as follows: vortexing, sonication (tube placed in Ultrasonik cleaning bath; NEY, Inc., Bloomfield, Conn.), vortexing, sonication, and final vortexing. They were serially diluted in distilled water, and 50-μl aliquots were inoculated into 1 ml of the catabolism assay mixtures.

Preparation of nodule extracts and catabolism assays.

Extracts containing MSI were obtained from alfalfa nodules induced by S. meliloti L5-30 under gnotobiotic conditions, as described previously (23). Five grams of nodules was crushed with a mortar and pestle in 25 ml of distilled water. The suspension was centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min to clarify the solution. The supernatant was filter sterilized, aliquoted, and kept frozen at −20°C. The total solute concentration of these 1× extracts was determined gravimetrically to be 0.5% (wt/vol), and the concentration of MSI in the extracts was estimated to be 0.01% (wt/vol) by high-voltage paper electrophoresis (HVPE) analysis (see below). Preparations containing synthetic scyllo-inosamine (SI) were provided by R. Hollingsworth (Michigan State University Department of Biochemistry). myo-Inositol was obtained commercially (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.).

The rhizopine catabolism assay used to define Moc activity was similar to that described previously (23). Assay mixtures contained 0.3× nodule extract in 1× BGTS (25 mM KH2PO4 [pH 7.3], 10 mM NaCl, MgSO4 · 7H2O, at 25 ppm, CaCl2 at 1.25 ppm, FeCl3 · 6H2O at 0.27 ppm, Na2MoO4 · 2H2O at 0.242 ppm, H3BO3 at 3 ppm, NaSO4 · H2O at 1.83 ppm, ZnSO4 · 7H2O at 0.287 ppm, CuSO4 · 5H2O at 0.125 ppm, CoSO4 · 6H2O at 0.119 ppm). Assay mixtures were incubated for 5 days in a rotary incubator at 28°C and 200 rpm. The mixtures were centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 × g to remove cell debris. The decanted supernatants were concentrated 10-fold by evaporation in a rotary Speed-Vac and resuspended in small volumes of sterile distilled water. Samples were stored at −20°C prior to analysis by HVPE. Ten microliters of each sample was loaded onto 3MM Whatman paper and air dried. Electrophoresis was performed at 3,000 V in 1.1 M acetic acid–0.7 M formic acid buffer. Visualization of α-diol-containing compounds, including MSI, resulted from staining with alkaline AgNO3 (5). The rhizopine was detected as a dark spot running at a characteristic distance relative to the position of the reference dye orange G (−0.9).

Catabolic units (CUs) were defined as the dilution factor of the most dilute suspension within which catabolism of rhizopine was observed by HVPE analysis after 5 days of incubation in the standard assay mixtures. In these assay mixtures, bacterial growth, as indicated by visible turbidity, was used to define the number of culture-forming units (CUFUs). Catabolism of SI and myo-inositol was scored in similar assay mixtures, where either 0.2% SI or 0.2% myo-inositol plus 0.1% (NH4)2SO4 was added in lieu of the nodule extract. Growth was scored by visual inspection for turbidity. In such instances, CUs were defined as the dilution factor of the most dilute suspension within which turbid growth was observed by eye after 5 days of incubation and were equivalent, by definition, to CUFUs.

Isolation and maintenance of bacteria.

To increase the diversity of isolates obtained, bacteria were isolated from the soil described above in several different ways. For the liquid enrichment cultures, samples included (i) air-dried soil (soil D), (ii) soil that had been saturated and kept at approximately field capacity for just over 5 months (soil W), and (iii) the crown rhizospheres of two separate 5-month-old alfalfa plants grown in this saturated soil (rhizospheres R and S). Samples (≤5 g each) were placed in 25 ml of distilled water, vigorously shaken for 15 s, and then diluted to the equivalent of 0.01 g/ml (wt/vol) in sterile distilled water. Seventy-five microliters of each mixture was separately inoculated into 1 ml of SI-containing medium (0.05% SI in 1× BGTS) and incubated at 28°C. After 3 days, the cultures were diluted and spread onto 0.1× tryptic soy agar (TSA) medium (3 g of tryptic soy extract per liter, 15 g of agar per liter) for isolation of individual colonies. Seventeen isolates representing several distinct morphotypes from each of the samples were selected for further analysis. Isolates were also obtained by selection of organisms growing on solid medium containing SI. Two soil samples (soils W2a and W2b) were obtained from the same pots as described above for soil W 2 months later. Additionally, four soil samples (soils Aa, Ab, Ba, and Bb) were obtained in late April 1996 from within 5 meters of the original sampling site in the field plot described above. Samples (≤4 g each) were diluted to 0.1 g/ml in 1× BGTS, mixed vigorously, serially diluted, and plated onto solid media [1% agarose with or without 0.2% SI with or without 0.1% (NH4)2SO4 or 0.1× TSA]. Plate counts were determined after 2, 4, and 8 days of incubation at 28°C. At the 4-day time point, 20 strains representing distinct morphotypes of the most abundant colonies were selected from each of the SI-containing plates and purified on 0.1× TSA medium. For all subsequent work, cultures were grown at 28°C on 0.1× tryptic soy broth (TSB; 3 g of tryptic soy extract per liter) or 0.1× TSA. Frozen stocks of purified isolates were kept in 15% glycerol at −70°C.

Characterization of bacterial isolates.

MagnaGraph nylon membranes (MSI Scientific, Westboro, Mass.) and random-primed digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes prepared with a Genius I kit (Boehringer Mannheim Biotechnologies, Indianapolis, Ind.) were used in all hybridization experiments according to the manufacturers’ instructions. When the isolates were screened for moc-like sequences, 10-μl samples of overnight cultures were spot inoculated onto 0.1× TSA and incubated for 24 h at 28°C prior to colony lifts. Probe templates consisted of the full-length ORFs of the mocA, mocB, and mocC genes from S. meliloti L5-30 carried by plasmids pSR8610 and pSR8611 (22, 23). For the characterization of strains D1, R3, and L5-30, genomic DNAs were isolated, digested, and transferred to nylon membranes according to standard procedures (26). Hybridizations were performed overnight at 68°C, and blots were subjected to two 10-min washes (0.1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate; ≥37°C). Genomic fingerprinting with the BOX primer was performed with whole cells, as described elsewhere (21).

In the nodulation assays, large test tubes containing 15 ml of a nitrogen-free mineral salts medium (1) and wicks of 3MM Whatman filter paper were autoclaved and allowed to cool to room temperature. Seeds of M. sativa var. Cardinal were surface sterilized by immersion in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by thorough rinsing in sterile distilled water. Two seeds were asceptically transferred onto the wick in each tube. Liquid cultures of the three bacterial strains were grown to saturation, pelleted by centrifugation, and washed twice with sterile distilled water. One hundred fifty-microliter samples (containing ≥107 cells) of these washed culture were individually used to inoculate test tubes. Four replicate tubes were prepared for each strain and for the uninoculated control.

Statistics.

The nonparametric sign test (17) was used for all comparisons. Differences in relative population sizes were conservatively estimated by finding the maximum factor which still yielded significant results in each of the comparisons. Tests were performed with SchoolStat software (David Darby, WhiteAnt Occasional Publishing, Victoria, Australia). All P values less than or equal to 0.15 are reported.

RESULTS

Detection and quantification of Moc activity in the environment.

Moc activity was detected in serial dilutions of soil and rhizosphere washes after 5 days of incubation in standard assay mixtures (Fig. 1). Since it could not be assumed that the breakdown of MSI in these assays was due to the activities of individual organisms, the enumeration of Moc activity in these assays is referred to in terms of CUs, which are analogous to CUFUs. The median Moc activity was observed to be 106 to 107 CUs per g (n = 6) in both soil and rhizosphere samples. The median myo-inositol-catabolizing activity was observed to be approximately fivefold higher, but this difference was not statistically significant. These data contrast with the median level of bacterial growth in these assays (P < 0.04), which was observed to be approximately 108 CUFUs per g. Bacterial growth in the assay mixtures increased with time and correlated well with the disappearance of uncharged organic compounds from the nodule extract as visualized by HVPE analysis. Catabolism of the uncharged compounds generally preceded catabolism of MSI (data not shown).

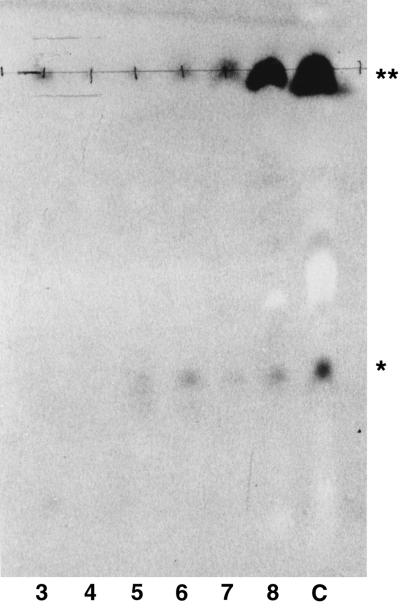

FIG. 1.

Detection of Moc activity in the environment. MSI in assay mixtures is detected as a positively staining spot ( ) with an electrophoretic mobility relative to that of orange G. Uncharged α-diol-containing organic compounds remain at the origin (

) with an electrophoretic mobility relative to that of orange G. Uncharged α-diol-containing organic compounds remain at the origin ( ). Moc activity is scored as the absence of a detectable signal comigrating with MSI after 5 days of incubation in the standard assay mix. To quantitate the observed activity, 10-fold serial dilutions (lanes 3 to 8) of soil and rhizosphere samples were assayed and compared to an uninoculated control (lane C). In this example, 104 CUs per g of Moc activity were detected.

). Moc activity is scored as the absence of a detectable signal comigrating with MSI after 5 days of incubation in the standard assay mix. To quantitate the observed activity, 10-fold serial dilutions (lanes 3 to 8) of soil and rhizosphere samples were assayed and compared to an uninoculated control (lane C). In this example, 104 CUs per g of Moc activity were detected.

The number of bacteria growing on the crude nodule extract was estimated to be just under 10 times that growing on myo-inositol as the sole carbon source (P < 0.11). Likewise, the number of CUFUs was approximately 10 times the number of units of Moc activity present in the assay mixtures (P < 0.11), though this ratio was measured to be ≥100 in half of the assays. Similarly, the number of colonies growing on SI-containing medium was less than the number growing on 0.1× TSA (P < 0.005). When the SI medium was supplemented with 0.1% (wt/vol) (NH4)2SO4, the number of colonies observed was intermediate between the numbers observed on SI medium and 0.1× TSA medium (P < 0.04). Again, the numbers of bacteria growing on SI-containing media were estimated to be approximately 10-fold less than the number growing on 0.1× TSA (P < 0.11).

Isolation and characterization of Moc+ bacteria.

Liquid and solid media containing SI were used to enrich for Moc+ bacteria from soil and rhizosphere samples. Thirty-seven isolates were selected for further investigation based on the type of enrichment used, the sample source, and the colony morphology of the isolate. All of these isolates were screened by colony hybridization for the presence of DNA sequences homologous to three of the known moc genes from S. meliloti L5-30 (Fig. 2). However, no hybridization was observed for any of the isolates.

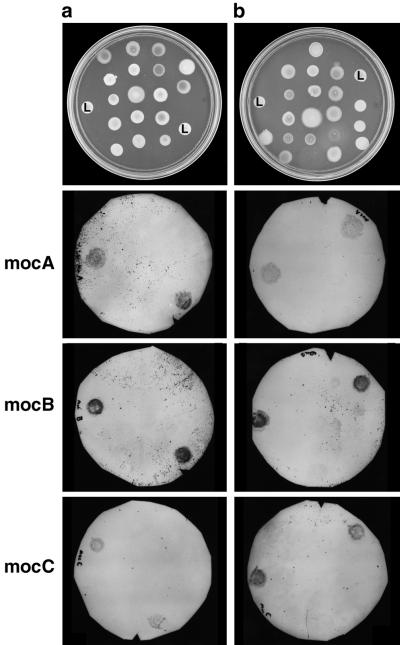

FIG. 2.

Colony hybridization of bacterial isolates with moc gene probes. DIG-labeled probes corresponding to the mocA, mocB, and mocC genes of S. meliloti L5-30 were hybridized to blots of colonies lifted from replica plates such as those shown. All 37 of the isolates obtained from liquid (a) and solid (b) media containing SI were examined. L5-30 (L) was included twice on all of the plates as a positive control.

Twenty-one of the isolates were found to be capable of growing on minimal medium containing the SI preparation as the sole carbon and nitrogen source (data not shown). Each of these strains was characterized by partial 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequencing. DNA sequence analysis revealed that several distinct phylogenetic groups were represented, including members of the gram-negative α, β, and γ subdivisions of the class Proteobacteria and a gram-positive phylum (Table 1). Amplified rDNA restriction analysis of representatives of each of these groups, with MspI and RsaI in single restriction digests, confirmed these designations (data not shown). The 16S rDNA sequences of strains that were determined to belong to the same genus were found to be ≥98% identical over the region analyzed. However, repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR genomic fingerprinting of these strains with the BOX primer revealed that most of the isolates were genotypically distinct (Fig. 3). Seventeen distinct patterns were observed in the set of 21 genomic fingerprints. Seven strains, all belonging to the γ proteobacteria based on their 16S rDNA sequences, were found to fall into three distinct groups based on their BOX-PCR-generated genomic fingerprints (isolates D2 and W2 and isolate D1). Additionally, some similarities were noted in the patterns generated from two sets of putative Arthrobacter strains (i.e. isolates R4 and S3 and isolates 1 and 1N). Interestingly, the putative S. meliloti strains D1 and R3 displayed BOX-genomic fingerprints that were distinctly different from that of S. meliloti L5-30.

TABLE 1.

Characterization of isolates capable of growing on the SI mix as the sole carbon and nitrogen source by partial sequencing of their 16 rDNAsa

| Enrichment | Sourceb | Strain | bp | Best sequence matchc | Sabd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid medium | Soil D | DI | 332 | Rhizobium meliloti | 0.855 |

| D2 | 381 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.921 | ||

| Soil W | W1 | 345 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.924 | |

| W2 | 337 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.914 | ||

| W4 | 316 | Pseudomonas putida mt-2 | 0.956 | ||

| W5 | 382 | Alcaligenes eutrophus 335 | 0.890 | ||

| Rhizosphere R | R1 | 394 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.939 | |

| R2 | 314 | Arthrobacter globiformuse | 0.538 | ||

| R3 | 333 | Rhizobium meliloti | 0.922 | ||

| R4 | 346 | Arthrobacter globiformus | 0.812 | ||

| Rhizosphere S | S1 | 335 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.904 | |

| S3 | 317 | Arthrobacter globiformus | 0.886 | ||

| Solid medium | Soil W2a | 1 | 315 | Arthrobacter globiformus | 0.990 |

| 1N | 273 | Arthrobacter globiformus | 0.982 | ||

| Soil W2b | 2 | 372 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.962 | |

| Soil Bb | 6 | 380 | Pseudomonas putida mt-2 | 0.916 | |

| 7 | 382 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.948 | ||

| Soil Ba | 11 | 388 | Aeromonas media | 0.923 | |

| Soil Ab | 14 | 384 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.924 | |

| 16 | 350 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.940 | ||

| Soil Aa | 18 | 372 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.763 | |

| 20 | 383 | Azospirillum sp. | 0.943 |

Strains found capable of catabolizing MSI are highlighted in bold.

See Materials and Methods for descriptions.

Best match with SIM_RANK software. DNA sequence differences were <2% over 300 bp of aligned sequence for isolates with the same phylogenetic match.

Sab, similarity value.

The low similarity value of this strain is due to a large number of ambiguous bases in the obtained sequence.

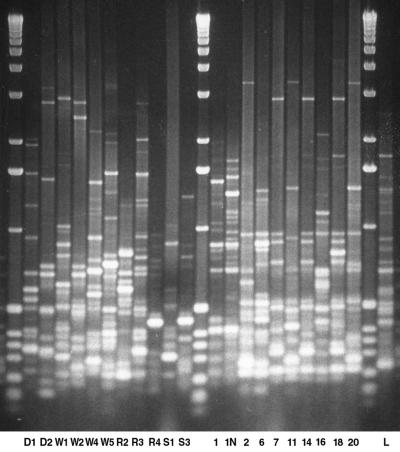

FIG. 3.

BOX-PCR-generated genomic fingerprints of isolates capable of growing on SI as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. Seventeen distinct patterns can be observed in the set of 21 genomic fingerprints obtained from the rhizopine-catabolizing isolates. Three sets of strains with very similar patterns were observed: D2 and W2 (lanes 2 and 6) and D1 (lanes 7, 14, and 18). Additionally, strains D1 and R3 had distinct BOX-genomic fingerprints from S. meliloti L5-30 (L).

Of the 21 isolates, only 6 were designated Moc+ based on their performance in the standard catabolism assay (Fig. 4). Four of these isolates, R4, S3, 1, and 1N, appeared to belong to the genus Arthrobacter, based on their 16S rDNA sequences. The other two strains, D1 and R3, appeared to be most closely related to S. meliloti, the species from which the moc genes were originally isolated (12, 23).

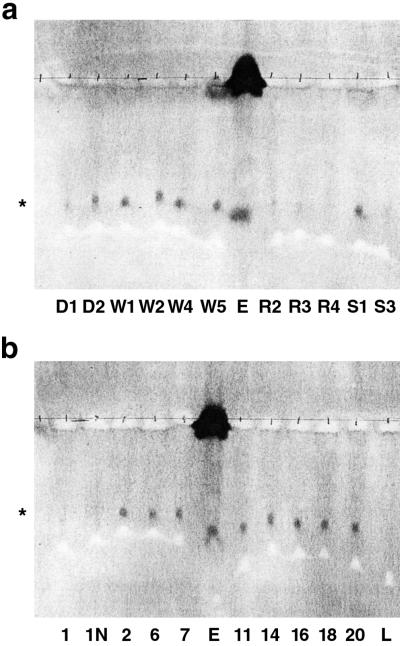

FIG. 4.

Determination of the Moc phenotypes of isolates. Twenty-one isolates capable of growth on SI were obtained from liquid (a) and solid (b) media and assayed for their ability to catabolize MSI ( ) in nodule extracts. L5-30 (lanes L) was included as a positive control for catabolism. An uninoculated assay mixture containing the MSI rhizopine from nodule extract (lanes E) was used as a negative control.

) in nodule extracts. L5-30 (lanes L) was included as a positive control for catabolism. An uninoculated assay mixture containing the MSI rhizopine from nodule extract (lanes E) was used as a negative control.

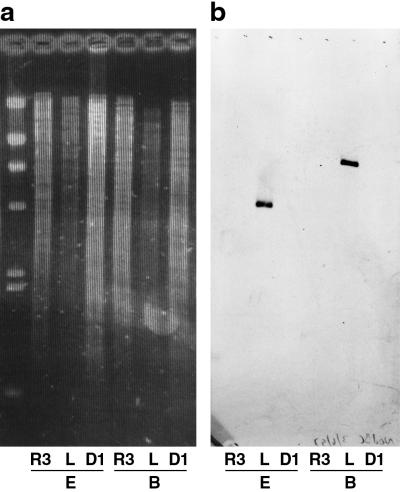

Because the moc gene probes did not hybridize to genomic DNAs from strains D1 and R3, these two putative S. meliloti strains were further analyzed. Attempts to amplify portions of the nifHDK and nodBC loci with conserved primers were unsuccessful despite amplification of appropriately sized fragments from S. meliloti L5-30 (data not shown). Additionally, no hybridization to a nodBC probe generated from the L5-30 sequence was observed (Fig. 5). Strains D1 and R3 also failed to nodulate alfalfa under gnotobiotic conditions.

FIG. 5.

Southern blot analysis of D1, R3, and L5-30 for the presence of nod gene sequences. (a) Ethidium-stained agarose gel containing 1 μg of genomic DNA from each of the three strains digested with either EcoRI (E lanes) or BamHI (B lanes). (b) Southern blot of the same gel hybridized with a DIG-labeled probe specific to 1 kb spanning the nodB and nodC genes of S. meliloti.

DISCUSSION

We have detected and characterized rhizopine-catabolizing activity in soil and rhizosphere environments, and we isolated a collection of novel rhizopine-catabolizing bacteria. Amounts of catabolic activity were enumerated by serial dilution of soil and rhizosphere washes (see Materials and Methods). Twenty-one bacterial strains capable of growing on synthetic SI were identified, six of which were found to be able to catabolize MSI under standard assay conditions. The abundance of two of these Moc+ strains, 1 and 1N, approximated the total number of rhizopine-catabolizing units in the soil, because they were representatives of the dominant morphotypes cultured on SI-containing solid medium (data not shown). Thus, while it is likely that we isolated only a subset of the entire diversity of rhizopine-catabolizing microbes from these samples, we have identified at least some of the more abundant strains.

DNA sequences similar to the known moc genes were not detected in any of the isolated organisms in dot blot and, in selected cases, Southern hybridization experiments. This was particularly surprising with regard to isolates D1 and R3, which were identified as S. meliloti based on the sequences of their 16S rRNA genes. In addition, previous reports have indicated that Moc+ S. meliloti strains contain moc genes that are very similar to those from L5-30 (24, 30, 31). Since it has been shown that the known moc genes are located on the large symbiotic plasmid in S. meliloti (12), D1 and R3 may be lacking all or part of that plasmid, as indicated by their nonsymbiotic phenotype on M. sativa. Thus, alternative genes responsible for MSI catabolism may be present in some strains of rhizobia, although it cannot be ruled out that highly diverse moc-like genes are present in these isolates.

One of the motivations for performing this study was to explore the potential impact of indigenous catabolizers on a “biased-rhizosphere” system based on rhizopine as the nutritional mediator. Rhizopines were hypothesized to be good candidates for rhizosphere nutritional mediation because only beneficial soil bacteria (i.e., nitrogen-fixing rhizobia) were known to catabolize these compounds (13, 23, 25). Additionally, some evidence indicated that catabolism of MSI may play a role in competitiveness of certain strains for nodule occupancy (9). Other compounds present in the root exudates of legumes may also act as nutritional mediators that stimulate nodulation by Rhizobium (8, 11). That nutritional mediators can stimulate other beneficial plant-microbe interactions has also been shown. The biological control of plant pathogens has been enhanced by the concurrent application of salicylate and bacteria capable of catabolizing it (2, 32). Thus, it seems possible to promote the beneficial activities of plant-associated microbes capable of catabolizing nutritional mediators.

It is reasonable to assume that nontarget microbial populations capable of catabolizing any given nutrient exist, and their response to that nutrient may complicate the predicted outcome of efforts to bias microbial communities with nutritional mediators. Ideally, the abundance and diversity of microbes capable of using a selected nutritional mediator should be minimal. Some evidence indicates that opine-catabolizing bacteria represent a relatively small fraction of the total number of culturable bacterial heterotrophs in soil and rhizosphere environments (20). However, we have observed that the numbers of soil bacteria capable of growing on mannopine, nopaline, or octopine as the sole carbon and nitrogen source were similar to those reported here for SI and myo-inositol plus (NH4)2SO4 (data not shown). This discrepancy may reflect differences in media composition and/or differences in the levels of abundance of indigenous catabolizers in different soils. Diverse types of bacteria, including members of Arthrobacter and Pseudomonas, have been reported to catabolize mannityl opines (15, 16, 19). The coincidental isolation of rhizopine catabolizers from these genera likely reflects the metabolic diversity that is known to be present in these two genera. Of course, plant-pathogenic Agrobacterium can also catabolize opines (5, 6). Because of this, opine-based nutritional mediators may not be suitable for biasing rhizosphere microbial populations in agricultural settings (19).

Other factors may also play significant roles in determining the effectiveness of nutritional mediators in the complex milieu of the rhizosphere environment. The relative numbers of target and nontarget catabolizers, their relative efficiencies in utilizing the nutritional mediator, and the consequences of their enrichment on microbial ecology in and around the plant roots may all be factors. In our catabolism assays, we have noticed that the catabolism of MSI appears to follow the catabolism of other α-diol-containing compounds present in the nodule extracts, both in the serial dilutions of environmental samples and in the Moc+ isolates (data not shown). This finding may indicate that MSI is not a preferred metabolic substrate for the microorganisms capable of catabolizing it. Additionally, the growth rate of the Moc+ isolates generally exceeded that of L5-30 both in the nodule extracts and in 0.1× TSB. To what extent these observations relate to a rhizopine-based biased rhizosphere in the field remains an open question.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Josiemeer Mattei and Baptiste Nault for their technical assistance in these experiments and related work. We also thank Mark Wilson and Silvia Rossbach for their critical reviews of the manuscript and many helpful discussions and Rawle Hollingsworth for providing SI preparation.

This work was supported in part by a grant from the USDA NRICGP (9501182) to M. Wilson, Auburn University, and by a STAR graduate fellowship from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to B.B.M.G.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown C M, Dilworth M J. Ammonia assimilation by Rhizobium cultures and bacteroids. J Gen Microbiol. 1975;86:39–48. doi: 10.1099/00221287-86-1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colbert S F, Hendson M, Ferri M, Schroth M N. Enhanced growth and activity of biocontrol bacterium genetically engineered to utilize salicylate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2071–2076. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2071-2076.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colbert S F, Isakeit T, Ferri M, Weinhold A R, Hendson M, Schroth M N. Use of an exotic carbon source to selectively increase metabolic activity and growth of Pseudomonas putida in soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2056–2063. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2056-2063.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colbert S F, Schroth M N, Weinhold A R, Hendson M. Enhancement of population densities of Pseudomonas putida PpG7 in agricultural ecosystems by selective feeding with the carbon source salicylate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2064–2070. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.7.2064-2070.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dessaux Y, Petit A, Tempe J. Opines in Agrobacterium biology. In: Verma D P S, editor. Molecular signals in plant-microbe communication. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 109–136. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dessaux Y, Petit A, Tempe J. Chemistry and biochemistry of opines, chemical mediators of parasitism. Phytochemistry. 1993;34:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldmann A, Boivin C, Fleury V, Message B, Lecoeur L, Maille M, Tepfer D. Betaine use by rhizosphere bacteria: genes essential for trigonelline, stachydrine, and carnititen catabolism in Rhizobium meliloti are located on pSym in the symbiotic region. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1991;6:571–578. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-4-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldmann A, Lecoeur L, Message B, Delarue M, Schoonejans E, Tepfer D. Symbiotic plasmid genes essential to the catabolisms of proline, betaine, or stachydrine are also required for efficient nodulation by Rhizobium meliloti. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;155:305–312. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordon D M, Ryder M H, Heinrich K H, Murphy P J. An experimental test of the rhizopine concept in Rhizobium meliloti. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3991–3996. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3991-3996.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyon P, Petit A, Tempe J, Dessaux Y. Transformed plants producing opines specifically promote growth of opine-degrading agrobacteria. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1993;6:92–98. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McSpadden Gardener, B., C. Cotton, and F. J. de Bruijn. 1998. Unpublished data.

- 12.Murphy P J, Heycke N, Banfalvi Z, Tate M E, de Bruijn F, Kondorosi A, Tempe J, Schell J. Genes for the catabolism and synthesis of an opine-like compound in R. meliloti are closely linked and on the Sym plasmid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:495–497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy P J, Saint C P. Rhizopines in the legume-Rhizobium symbiosis. In: Verma D P S, editor. Molecular signals in plant-microbe communication. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1992. pp. 377–390. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy P J, Wexler W, Grzemski W, Rao J P, Gordon D. Rhizopines—their role in symbiosis and competition. Soil Biol Biochem. 1995;27:525–529. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nautiyal C S, Dion P, Chilton W S. Mannopine and mannopinic acid as substrates for Arthrobacter sp. strain MBA209 and Pseudomonas putida NA513. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2833–2841. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2833-2841.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nautiyal C S, Dion P. Characterization of the opine-utilizing microflora associated with samples of soil and plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2576–2579. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.8.2576-2579.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neave H R, Worthington P L. Distribution-free tests. New York, N.Y: Chapman and Hall; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connel K P, Goodman R M, Handelsman J. Engineering the rhizosphere: expressing a bias. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oger P. Etudes sur la possibilité de favoriser specifiquement la croissance de bacteries de la rhizosphère—le cas des plantes transgéniques productrices d’opines. Ph.D. thesis. D’Orsay, France: Université de Paris Sud, Centre D’Orsay; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oger P, Petit A, Dessaux Y. Genetically engineered plants producing opines alter their biological environment. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:369–372. doi: 10.1038/nbt0497-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rademaker J L W, de Bruijn F J. Characterization and classification of microbes by rep-PCR genomic fingerprinting and computer assisted pattern analysis. In: Caeteno-Anolles G, Gresshoff P M, editors. DNA markers: protocols, applications and overviews. J. New York, N.Y: Wiley & Sons; 1997. pp. 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rossbach, S., and F. J. de Bruijn. (Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich.). 1994. Unpublished data.

- 23.Rossbach S, Kulpa D A, Rossbach U, de Bruijn F J. Molecular and genetic characterization of the rhizopine catabolism (mocABRC) genes of Rhizobium meliloti L5-30. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;245:11–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00279746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossbach S, Rasul G, Schneider M, Eardly B, de Bruijn F J. Structural and functional conservation of the rhizopine catabolism (moc) locus is limited to selected Rhizobium meliloti strains and unrelated to their geographical origin. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1995;8:549–559. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossbach S R, McSpadden B, Kulpa D, de Bruijn F J. Rhizopine synthesis and catabolism genes for the creation of “biased rhizospheres” and as marker system to detect (genetically modified) microorganisms in the soil. In: Levin M, Grim C, Angle J S, editors. Biotechnology risk assessment: proceedings of the Biotechnology Risk Assessment Symposium. 1995. pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Savka M A, Farrand S K. Modification of rhizobacterial populations by engineering bacterium utilizations of a novel plant-produced resource. Nat Biotechnol. 1997;15:363–368. doi: 10.1038/nbt0497-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tempe J, Petit A, Bannerot H. Presence de substances semblables à des opines dans des nodosites de luzerne. C R Acad Sci Ser III. 1982;295:413–416. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tepfer D, Goldmann A, Pamboukdjian N, Maille M, Lepingle A, Chevalier D, Dénarié J, Rosenberg C. A plasmid of Rhizobium meliloti 41 encodes catabolism of two compounds from root exudate of Calysegium sepium. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1153–1161. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1153-1161.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wexler M, Gordon D, Murphy P J. The distribution of inositol rhizopine genes in Rhizobium populations. Soil Biol Biochem. 1995;27:531–537. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wexler M, Gordon D M, Murphy P J. Genetic relationships among rhizopine-producing Rhizobium strains. Microbiology. 1996;142:1059–1066. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson, M. (Auburn University, Auburn, Ala.). 1998. Personal communication.

- 33.Wilson M, Lindow S E. Coexistence among epiphytic bacterial populations mediated through nutritional resource partitioning. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4468–4477. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4468-4477.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson M, Lindow S E. Enhanced epiphytic coexistence of near-isogenic salicylate-catabolizing and non-salicylate-catabolizing Pseudomonas putica strains after exogenous salicylate application. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1073–1076. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.3.1073-1076.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson M, Savka M A, Whang I, Farrand S K, Lindow S E. Altered epiphytic colonization of mannityl opine-producing transgenic tobacco plants by a mannityl opine-catabolizing strain of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2151–2158. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2151-2158.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]