Abstract

Cellular respiration is essential for multiple bacterial pathogens and a validated antibiotic target. In addition to driving oxidative phosphorylation, bacterial respiration has a variety of ancillary functions that obscure its contribution to pathogenesis. We find here that the intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes encodes two respiratory pathways which are partially functionally redundant and indispensable for pathogenesis. Loss of respiration decreased NAD+ regeneration, but this could be specifically reversed by heterologous expression of a water-forming NADH oxidase (NOX). NOX expression fully rescued intracellular growth defects and increased L. monocytogenes loads >1000-fold in a mouse infection model. Consistent with NAD+ regeneration maintaining L. monocytogenes viability and enabling immune evasion, a respiration-deficient strain exhibited elevated bacteriolysis within the host cytosol and NOX expression rescued this phenotype. These studies show that NAD+ regeneration represents a major role of L. monocytogenes respiration and highlight the nuanced relationship between bacterial metabolism, physiology, and pathogenesis.

Research organism: Other

eLife digest

Cellular respiration is one of the main ways organisms make energy. It works by linking the oxidation of an electron donor (like sugar) to the reduction of an electron acceptor (like oxygen). Electrons pass between the two molecules along what is known as an ‘electron transport chain’. This process generates a force that powers the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a molecule that cells use to store energy.

Respiration is a common way for cells to replenish their energy stores, but it is not the only way. A simpler process that does not require a separate electron acceptor or an electron transport chain is called fermentation. Many bacteria have the capacity to perform both respiration and fermentation and do so in a context-dependent manner.

Research has shown that respiration can contribute to bacterial diseases, like tuberculosis and listeriosis (a disease caused by the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes). Indeed, some antibiotics even target bacterial respiration. Despite being often discussed in the context of generating ATP, respiration is also important for many other cellular processes, including maintaining the balance of reduced and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) cofactors. Because of these multiple functions, the exact role respiration plays in disease is unknown.

To find out more, Rivera-Lugo, Deng et al. developed strains of the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes that lacked some of the genes used in respiration. The resulting bacteria were still able to produce energy, but they became much worse at infecting mammalian cells. The use of a genetic tool that restored the balance of reduced and oxidized NAD cofactors revived the ability of respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes to infect mammalian cells, indicating that this balance is what the bacterium requires to infect.

Research into respiration tends to focus on its role in generating ATP. But these results show that for some bacteria, this might not be the most important part of the process. Understanding the other roles of respiration could change the way that researchers develop antibacterial drugs in the future. This in turn could help with the growing problem of antibiotic resistance.

Introduction

Distinct metabolic strategies allow microbes to extract energy from diverse surroundings and colonize nearly every part of the earth. Microbial energy metabolisms vary greatly but can be generally categorized as possessing fermentative or respiratory properties. Cellular respiration is classically described by a multistep process that initiates with the enzymatic oxidation of organic matter and the accompanying reduction of NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) to NADH. Respiration of fermentable sugars typically starts with glycolysis, which generates pyruvate and NADH. Pyruvate then enters the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, where its oxidation to carbon dioxide is coupled to the production of additional NADH. NADH generated by glycolysis and the TCA cycle is then oxidized by NADH dehydrogenase to regenerate NAD+ and the resulting electrons are transferred via an electron transport chain to a terminal electron acceptor.

While mammals strictly use oxygen as a respiratory electron acceptor, microbes reside in diverse oxygen-limited environments and have varying and diverse capabilities to use disparate non-oxygen respiratory electron acceptors. Whatever the electron acceptor, electron transfer in the electron transport chain is often coupled to proton pumping across the bacterial inner membrane. This generates a proton gradient or proton motive force, which powers a variety of processes, including ATP production by ATP synthase.

Respiratory pathways are important for several aspects of bacterial physiology. Respiration’s role in establishing the proton motive force allows bacteria to generate ATP from non-fermentable energy sources (which are not amenable to ATP production by substrate-level phosphorylation) and increases ATP yields from fermentable energy sources. In addition to these roles in ATP production, respiratory electron transport chains are directly involved in many other aspects of bacterial physiology, including the regulation of cytosolic pH, transmembrane solute transport, ferredoxin-dependent metabolisms, protein secretion, protein folding, disulfide formation, and flagellar motility (Bader et al., 1999; Driessen et al., 2000; Driessen and Nouwen, 2008; Manson et al., 1977; Slonczewski et al., 2009; Driessen et al., 2000; Tremblay et al., 2013; Wilharm et al., 2004). Beyond the proton motive force, respiration functions to regenerate NAD+, which is essential for enabling the continued function of glycolysis and other metabolic processes. By obviating fermentative mechanisms of NAD+ regeneration, respiration increases metabolic flexibility, which, among other metabolic consequences, can enhance ATP production by substrate-level phosphorylation (Hunt et al., 2010).

Bacterial pathogens reside within a host where they must employ fermentative or respiratory metabolisms to power growth. Pathogen respiratory processes have been linked to host-pathogen conflict in several contexts. Phagocytic cells target bacteria by producing reactive nitrogen species that inhibit aerobic respiration (Richardson et al., 2008). Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Salmonella enterica, Streptococcus agalactiae, and Staphylococcus aureus mutants with impaired aerobic respiration are attenuated in murine models of systemic disease (Craig et al., 2013; Hammer et al., 2013; Jones-Carson et al., 2016; Lencina et al., 2018; Lewin et al., 2019; Rivera-Chávez et al., 2016). Aerobic respiration is vital for Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and persister cell survival, making respiratory systems validated anti-tuberculosis drug targets (Cook et al., 2014; Hasenoehrl et al., 2020). Respiratory processes that use oxygen, tetrathionate, and nitrate as electron acceptors are important for the growth of S. enterica and Escherichia coli in the mammalian intestinal lumen (Rivera-Chávez et al., 2016; Winter et al., 2010; Winter et al., 2013). While several studies have linked respiration in bacterial pathogens to the use of specific electron donors (i.e. non-fermentable energy sources) within the intestinal lumen, the particular respiratory functions important for systemic bacterial infections remain largely unexplained (Ali et al., 2014; Faber et al., 2017; Gillis et al., 2018; Spiga et al., 2017; Thiennimitr et al., 2011).

Listeria monocytogenes is a human pathogen that, after being ingested on contaminated food, can gain access to the host cell cytosol and use actin-based motility to spread from cell to cell (Freitag et al., 2009). L. monocytogenes has two respiratory-like electron transport chains. One electron transport chain is dedicated to aerobic respiration and uses a menaquinone intermediate and QoxAB (aa3) or CydAB (bd) cytochrome oxidases for terminal electron transfer to O2 (Figure 1A; Corbett et al., 2017). We recently identified a second flavin-based electron transport chain that transfers electrons to extracytosolic acceptors (including ferric iron and fumarate) via a putative demethylmenaquinone intermediate and can promote growth in anaerobic conditions (Figure 1A; Light et al., 2018; Light et al., 2019; Zeng et al., 2021). Final electron transfer steps in this flavin-based electron transport mechanism are catalyzed by PplA and FrdA, which are post-translationally linked to an essential cofactor by the flavin mononucleotide transferase (FmnB) (Light et al., 2018; Méheust et al., 2021).

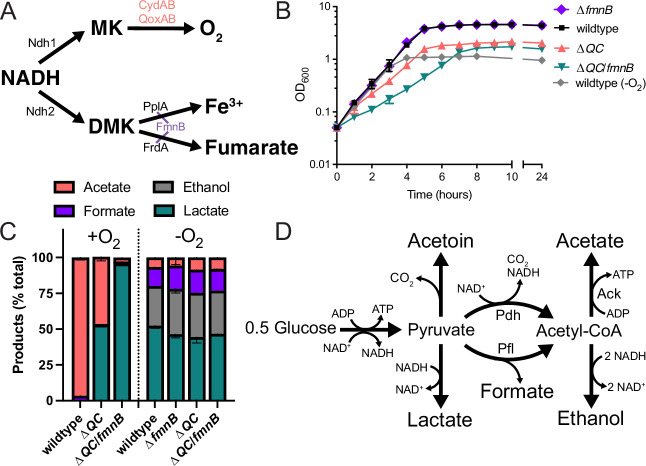

Figure 1. Respiration impacts L. monocytogenes growth and fermentative output.

(A) Proposed respiratory electron transport chains in L. monocytogenes. Different NADH dehydrogenases likely transfer electrons to distinct but presently unidentified quinones (Qa and Qb). FmnB catalyzes assembly of essential components of the electron transport chain, PplA and FrdA, that can transfer electrons to ferric iron and fumarate, respectively. Other proteins involved in the terminal electron transfer steps are noted. (B) Optical density of L. monocytogenes strains aerobically grown in nutrient-rich media, with the anaerobically grown wildtype strain provided for context. The means and standard deviations from three independent experiments are shown. (C) Fermentation products of L. monocytogenes strains grown to stationary phase in nutrient-rich media under aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Error bars show standard deviations. Results from three independent experiments are shown. (D) Proposed pathways for L. monocytogenes sugar metabolism. The predicted number of NADH generated (+) or consumed (−) in each step is indicated. PplA, peptide pheromone-encoding lipoprotein A; FrdA, fumarate reductase; ΔQC, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB; ΔQC/fmnB, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB/fmnB::tn; GLC, glucose; Ack, acetate kinase; Pdh, pyruvate dehydrogenase; Pfl, pyruvate formate-lyase; DMK, demethylmenaquinone.

Figure 1—figure supplement 1. Use of respiratory electron acceptors enhances Listeria monocytogenes growth in nutrient-rich media.

L. monocytogenes resembles fermentative microbes in lacking a functional TCA cycle (Trivett and Meyer, 1971). Despite thus being unable to completely oxidize sugar substrates, previous studies have shown that aerobic respiration is important for the systemic spread of L. monocytogenes (Chen et al., 2017; Corbett et al., 2017; Stritzker et al., 2004). Microbes that similarly contain a respiratory electron transport chain but lack a TCA cycle are considered to employ a respiro-fermentative metabolism (Pedersen et al., 2012). Respiro-fermentative metabolisms tune the cell’s fermentative output and often manifest with the respiratory regeneration of NAD+ enabling a shift from the production of reduced (e.g. lactic acid and ethanol) to oxidized (e.g. acetic acid) fermentation products. In respiro-fermentative lactic acid bacteria closely related to L. monocytogenes, cellular respiration results in a modest growth enhancement, but is generally dispensable (Duwat et al., 2001; Pedersen et al., 2012).

The studies presented here sought to address the role of respiration in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis. Our results confirm that L. monocytogenes exhibits a respiro-fermentative metabolism and show that its two respiratory systems are partially functionally redundant under aerobic conditions. We find that the respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains exhibit severely attenuated virulence and lyse within the cytosol of infected cells. Finally, we selectively abrogate the effect of diminished NAD+ regeneration in respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains by heterologous expression of a water-forming NADH oxidase (NOX) and find that this restores virulence. These results thus elucidate the basis of L. monocytogenes cellular respiration and demonstrate that NAD+ regeneration represents a key function of this activity in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis.

Results

L. monocytogenes’ electron transport chains have distinct roles in aerobic and anaerobic growth

We selected previously characterized ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB (ΔQC) and ΔfmnB L. monocytogenes strains to study the role of aerobic respiration and extracellular electron transfer, respectively (Chen et al., 2017; Light et al., 2018). In addition, we generated a ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB/fmnB::tn (ΔQC/fmnB) L. monocytogenes strain to test for functional redundancies of aerobic respiration and extracellular electron transfer. Initial studies measured the growth of these strains on nutritionally rich brain heart infusion (BHI) media in the presence/absence of electron acceptors.

Compared to anaerobic conditions that lacked an electron acceptor, we found that aeration led to a relatively modest increase in growth of wildtype and ΔfmnB strains (Figure 1B and Figure 1—figure supplement 1a). This growth enhancement could be attributed to aerobic respiration, as aerobic growth of the ΔQC strain resembled anaerobically cultured strains (Figure 1B and Figure 1—figure supplement 1a). Similarly, in anaerobic conditions, inclusion of the extracellular electron acceptors, ferric iron and fumarate, resulted in a small growth enhancement of wildtype L. monocytogenes (Figure 1—figure supplement 1b). This phenotype could be attributed to extracellular electron transfer, as ferric iron or fumarate failed to stimulate growth of the ΔfmnB strain (Figure 1—figure supplement 1b). These findings are consistent with aerobic respiration and extracellular electron transfer possessing distinct roles in aerobic and anaerobic environments, respectively.

The ΔQC/fmnB strain exhibited the most striking growth pattern. This strain lacked a phenotype under anaerobic conditions but had impaired aerobic growth, even relative to the ΔQC strain (Figure 1B). Notably, ΔQC/fmnB was the sole strain tested with a substantially reduced growth rate in the presence of oxygen (Figure 1B). These observations suggest that aerobic extracellular electron transfer activity can partially compensate for the loss of aerobic respiration and that oxygen inhibits L. monocytogenes growth in the absence of both electron transport chains.

Respiration alters L. monocytogenes’ fermentative output

Respiration is classically defined by the complete oxidation of an electron donor (e.g. glucose) to carbon dioxide in the TCA cycle. However, L. monocytogenes lacks a TCA cycle and instead converts sugars into multiple fermentation products (Romick et al., 1996). We thus asked how respiration impacts L. monocytogenes’ fermentative output. Under anaerobic conditions that lacked an alternative electron acceptor, L. monocytogenes exhibited a pattern of mixed acid fermentation, with lactic acid being most abundant and ethanol, formic acid, and acetic acid being produced at lower levels (Figure 1C). By contrast, under aerobic conditions L. monocytogenes almost exclusively produced acetic acid (Figure 1C). Consistent with respiration being partially responsible for the distinct aerobic vs. anaerobic responses, ΔQC and ΔQC/fmnB strains failed to undergo drastic shifts in fermentative output when grown in aerobic conditions. The ΔQC strain mainly produced lactic acid in the presence of oxygen, and this trend was even more pronounced in the ΔQC/fmnB strain, which almost exclusively produced lactic acid (Figure 1C). These results show that aerobic respiration induces a shift to acetic acid production and support the conclusion that L. monocytogenes’ two electron transport chains are partially functionally redundant in aerobic conditions.

A comparison of fermentative outputs across the experimental conditions also clarifies the basis of central energy metabolism in L. monocytogenes. A classical glycolytic metabolism in L. monocytogenes likely generates ATP and NADH. In the absence of oxygen or an alternative electron acceptor, NAD+ is regenerated by coupling NADH oxidation to the reduction of pyruvate to lactate or ethanol. In the presence of oxygen, NADH oxidation is coupled to the reduction of oxygen, and pyruvate is converted to acetate. Moreover, the pattern of anaerobic formate production is consistent with aerobic acetyl-CoA production through pyruvate dehydrogenase and anaerobic production through pyruvate formate-lyase (Figure 1D). Collectively, these observations suggest that L. monocytogenes prioritizes balancing NAD+/NADH levels in the absence of an electron acceptor and maximizing ATP production in the presence of oxygen. In the absence of oxygen, NAD+/NADH redox homeostasis is achieved by minimizing NADH produced in acetyl-CoA biosynthesis and by consuming NADH in lactate/ethanol fermentation (Figure 1D). In the presence of oxygen, ATP yields are maximized through respiration and increased substrate-level phosphorylation by acetate kinase activity (Figure 1D).

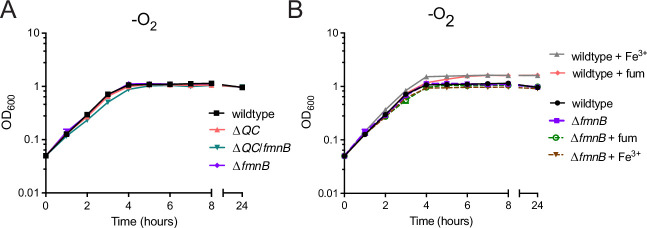

Respiratory capabilities are essential for L. monocytogenes pathogenesis

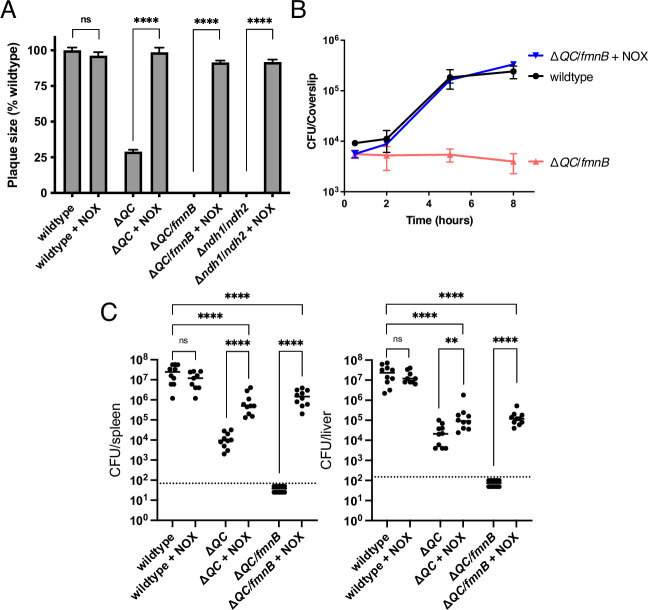

We next asked about the role of cellular respiration in intracellular L. monocytogenes growth and pathogenesis. The ΔfmnB mutant deficient for extracellular electron transfer was previously shown to resemble the wildtype L. monocytogenes strain in a murine model of infection (Light et al., 2018). We found that this mutant also did not differ from wildtype L. monocytogenes in growth in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) and a plaque assay that monitors bacterial growth and cell-to-cell spread (Figure 2A and B). Consistent with previous reports, the ΔQC strain deficient for aerobic respiration was attenuated in the plaque assay and murine model of infection, but resembled wildtype L. monocytogenes in macrophage growth (Figure 2A–C; Chen et al., 2017; Corbett et al., 2017). Combining mutations that resulted in the loss of both extracellular electron transfer and aerobic respiration produced even more pronounced phenotypes. The ΔQC/fmnB strain did not grow intracellularly in macrophages and fell below the limit of detection in the plaque assay and murine infection model (Figure 2A–C). Consistent with this phenotype reflecting a loss of respiratory activity, we observed that a mutant that targeted the two respiratory NADH dehydrogenases resulted in a similar phenotype in the plaque assay (Figure 2A). These results thus demonstrate that respiratory activities are essential for L. monocytogenes virulence, and that the organism’s two respiratory pathways are partially functionally redundant within a mammalian host.

Figure 2. Respiration is required for L. monocytogenes virulence.

(A) Plaque formation by cell-to-cell spread of L. monocytogenes strains in monolayers of mouse L2 fibroblast cells. The mean plaque size of each strain is shown as a percentage relative to the wildtype plaque size. Error bars represent standard deviations of the mean plaque size from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test comparing wildtype to all the other strains. ****, p<0.0001; ns, no significant difference (p>0.05). (B) Intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes strains in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). At 1-hour post-infection, infected BMMs were treated with 50 μg/mL of gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. Colony-forming units (CFU) were enumerated at the indicated times. Results are representative of two independent experiments. (C) Bacterial burdens in murine spleens and livers 48 hours post-intravenous infection with indicated L. monocytogenes strains. The median values of the CFUs are denoted by black bars. The dashed lines represent the limit of detection. Data were combined from two independent experiments, n = 10 mice per strain. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test using wildtype as the control. ****, p<0.0001. ΔQC, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB; ΔQC/fmnB, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB/fmnB::tn; Δndh1/ndh2, Δndh1/ndh2::tn.

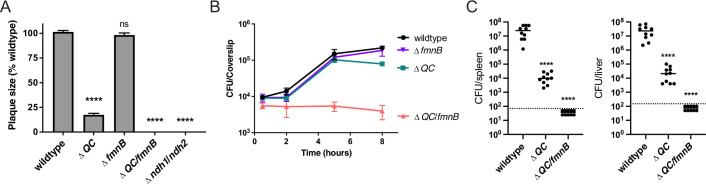

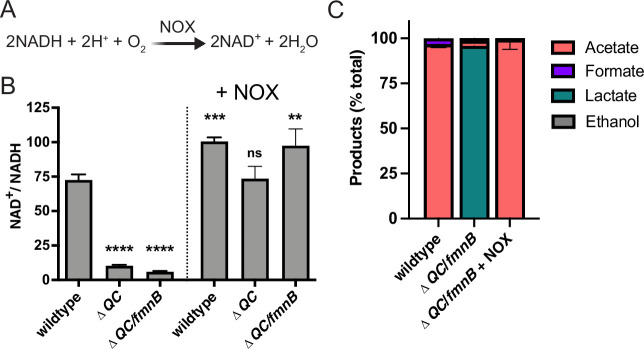

Expression of NOX restores NAD+ levels in L. monocytogenes respiration mutants

Cellular respiration both regenerates NAD+ and establishes a proton motive force that is important for various aspects of bacterial physiology. The involvement of respiration in these two distinct processes can confound the analysis of respiration-impaired phenotypes. However, the heterologous expression of water-forming NADH oxidase (NOX) has been used to decouple these functionalities in mammalian cells (Figure 3A; Titov et al., 2016). Because NOX regenerates NAD+ without pumping protons across the membrane, its introduction to a respiration-deficient cell can correct the NAD+/NADH imbalance, thereby isolating the role of the proton motive force in the phenotype (Lopez de Felipe et al., 1998; Titov et al., 2016).

Figure 3. Water-forming NADH oxidase (NOX) restores redox homeostasis in respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains.

(A) Reaction catalyzed by the Lactococcus lactis water-forming NOX, which is the same as aerobic respiration without the generation of a proton motive force. (B) NAD+/NADH ratios of parent and NOX-complemented L. monocytogenes strains grown aerobically in nutrient-rich media to mid-logarithmic phase. Results from three independent experiments are presented as means and standard deviations. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test using the wildtype parent strain as the control. ****, p<0.0001; ***, p<0.001; **, p<0.01; ns, not statistically significant (p>0.05). (C) Fermentation products of L. monocytogenes strains grown in nutrient-rich media under aerobic conditions. Error bars show standard deviations. Results from three independent experiments are shown. ΔQC, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB; ΔQC/fmnB, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB/fmnB::tn; + NOX, strains complemented with L. lactis nox.

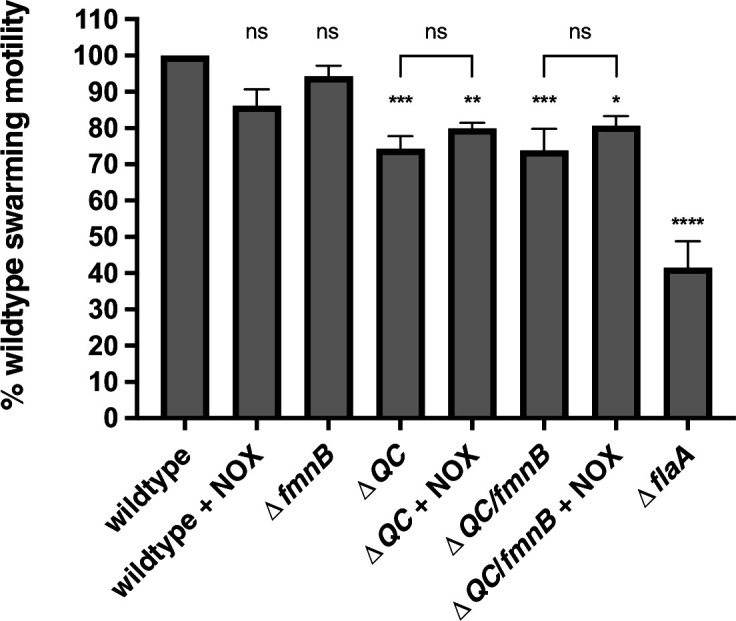

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. NOX expression in respiration-deficient mutants fails to rescue swarming motility.

To address which aspect of cellular respiration was important for L. monocytogenes pathogenesis, we introduced the previously characterized Lactococcus lactis water-forming NOX to the genome of respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains (Heux et al., 2006; Neves et al., 2002a; Neves et al., 2002b). We confirmed that the ΔQC and ΔQC/fmnB strains exhibited decreased NAD+/NADH levels and that constitutive expression of NOX rescued this phenotype (Figure 3B). Consistent with the altered fermentative output of the ΔQC/fmnB strain resulting from impaired NAD+ regeneration, we observed that NOX expression restored the predominance of acetic acid production to the aerobically grown cells (Figure 3C).

To confirm that NOX expression specifically impacts NAD+/NADH-dependent phenotypes, we tested the effect of NOX expression on bacterial motility. Consistent with respiration impacting flagellar function through the proton motive force, we found that ΔQC/fmnB exhibited impaired bacterial motility and that this phenotype was resilient to NOX expression (Manson et al., 1977; Figure 3—figure supplement 1). These experiments thus provide evidence that NOX expression provides a tool to specifically manipulate the NAD+/NADH ratio in L. monocytogenes.

Respiration is critical for regenerating NAD+ during L. monocytogenes pathogenesis

We next sought to dissect the relative importance of respiration in generating a proton motive force versus maintaining redox homeostasis for L. monocytogenes virulence. We tested NOX-expressing ΔQC and ΔQC/fmnB strains for macrophage growth, plaque formation, and in the murine infection model. Expression of NOX almost fully rescued the plaque and macrophage growth phenotypes of the ΔQC and ΔQC/fmnB strains (Figure 4A and B). NOX expression also partially rescued L. monocytogenes virulence in the murine infection model (Figure 4C). Notably, NOX expression had a greater impact on the L. monocytogenes load in the spleen than the liver, suggesting distinct functions of respiration for L. monocytogenes colonization of these two organs (Figure 4C). These results thus suggest that NAD+ regeneration represents the primary role of respiration in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis to an organ-specific extent.

Figure 4. NOX expression restores virulence to respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains.

(A) Plaque formation by cell-to-cell spread of L. monocytogenes strains in monolayers of mouse L2 fibroblast cells. The mean plaque size of each strain is shown as a percentage relative to the wildtype plaque size. Error bars represent standard deviations of the mean plaque size from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed t test. ****, p<0.0001; ns, no significant difference (p>0.05). (B) Intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes strains in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs). At 1-hour post-infection, infected BMMs were treated with 50 μg/mL of gentamicin to kill extracellular bacteria. Colony-forming units (CFU) were enumerated at the indicated times. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (C) Bacterial burdens in murine spleens and livers 48 hours post-intravenous infection with indicated L. monocytogenes strains. The median values of the CFUs are denoted by black bars. The dashed lines represent the limit of detection. Data were combined from two independent experiments, n = 10 mice per strain, but for the wildtype +NOX strain (n = 9 mice). Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test using the wildtype control strain to compare with the NOX-complemented strains. Significance between the parental and the NOX-complemented strains was determined using the unpaired two-tailed t test. ****, p<0.0001; **, p<0.01; ns, no significant difference (p>0.05). ΔQC, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB; ΔQC/fmnB, ΔqoxA/ΔcydAB/fmnB::tn; Δndh1/ndh2, Δndh1/ndh2::tn; + NOX, strains complemented with Lactococcus lactis nox.

Impaired redox homeostasis is associated with increased cytosolic L. monocytogenes lysis

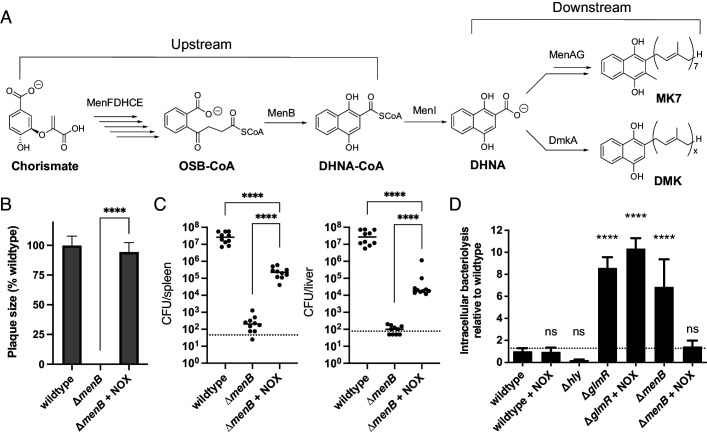

We next asked why respiration-mediated redox homeostasis was critical for L. monocytogenes pathogenesis. We reasoned that previous descriptions of L. monocytogenes quinone biosynthesis mutants might provide a clue. Quinones are a family of redox-active cofactors that have essential functions in respiratory electron transport chains (Collins and Jones, 1981). Our previous studies suggested that distinct quinones function in flavin-based electron transfer and aerobic respiration (Light et al., 2018). A separate set of studies found that L. monocytogenes quinone biosynthesis mutants exhibited divergent phenotypes. L. monocytogenes strains defective in upstream steps of the quinone biosynthesis pathway (menB, menC, menD, menE, and menF) exhibited increased bacteriolysis in the cytosol of host cells and were severely attenuated for virulence (Figure 5A). By contrast, L. monocytogenes strains defective in downstream steps of the quinone biosynthesis pathway (menA and menG) did not exhibit increased cytosolic bacteriolysis and had less severe virulence phenotypes (Chen et al., 2019, Chen et al., 2017; Smith et al., 2021; Figure 5A). These divergent phenotypic responses resemble the loss of aerobic respiration versus the loss of aerobic respiration plus flavin-based electron transfer observed in our studies. The distinct virulence phenotype of quinone biosynthesis mutants could thus be explained by the upstream portion of the quinone biosynthesis pathway being required for both aerobic respiration and flavin-based electron transfer, with the downstream portion of the pathway only being required for aerobic respiration (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Impaired redox homeostasis accounts for elevated bacteriolysis of a respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strain in the cytosol of infected cells.

(A) Proposed L. monocytogenes quinone biosynthesis pathway. Arrows indicate the number of enzymes that catalyze each reaction. An unidentified demethylmenaquinone (DMK) is proposed to be required for the flavin-based electron transfer pathway and MK7 required for aerobic respiration. Loss of the upstream portion of the pathway is anticipated to impact both electron transport chains. (B) Plaque formation by cell-to-cell spread of L. monocytogenes strains in monolayers of mouse L2 fibroblast cells. The mean plaque size of each strain is shown as a percentage relative to the wildtype plaque size. Error bars represent standard deviations of the mean plaque size from two independent experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using the unpaired two-tailed t test. ****, p<0.0001. (C) Bacterial burdens in murine spleens and livers 48 hours post-intravenous infection with indicated L. monocytogenes strains. The median values of the CFUs are denoted by black bars. The dashed lines represent the limit of detection. Data were combined from two independent experiments, n = 10 mice per strain. Statistical significance was evaluated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test using the wildtype strain as the control to compare with the NOX-complemented strain. Significance between the parental and the NOX-complemented strain was determined using the unpaired two-tailed t test. ****, p<0.0001. (D) Bacteriolysis of L. monocytogenes strains in bone marrow-derived macrophages. The data are normalized to wildtype bacteriolysis levels and presented as means and standard deviations from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was calculated using one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s post-test using the wildtype parent strain as the control. ****, p<0.0001; ns, no significant difference (p>0.05).

Based on the proposed roles of quinones in respiration, we hypothesized that the severe phenotypes previously described for the upstream quinone biosynthesis mutants were due to an imbalance in the NAD+/NADH ratio. To address this hypothesis, we first confirmed that the ΔmenB strain, which is defective in upstream quinone biosynthesis, exhibited a phenotype similar to the ΔQC/fmnB strain for plaque formation and in the murine infection model (Figure 5B and C). We next tested the effect of NOX expression on virulence phenotypes for the ΔmenB strain. NOX expression rescued ΔmenB phenotypes for plaque formation and in the murine infection model to a strikingly similar extent as the ΔQC/fmnB strain (Figure 5B and C). These results thus provide evidence that quinone biosynthesis is essential for respiration and that the severity of the ΔmenB phenotype is largely due to the role of respiration in regenerating NAD+.

Numerous adaptations allow L. monocytogenes to colonize the host cytosol, including resistance to bacteriolysis. Minimizing bacteriolysis within the host cytosol is important to the pathogen because it can activate the host’s innate immune responses, including pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death, which severely reduces L. monocytogenes virulence (Sauer et al., 2010). L. monocytogenes strains deficient for the upstream quinone biosynthesis steps were previously identified as having an increased susceptibility to bacteriolysis in the macrophage cytosol (Chen et al., 2017). We thus hypothesized that decreased virulence of respiration-deficient strains might relate to increased cytosolic bacteriolysis.

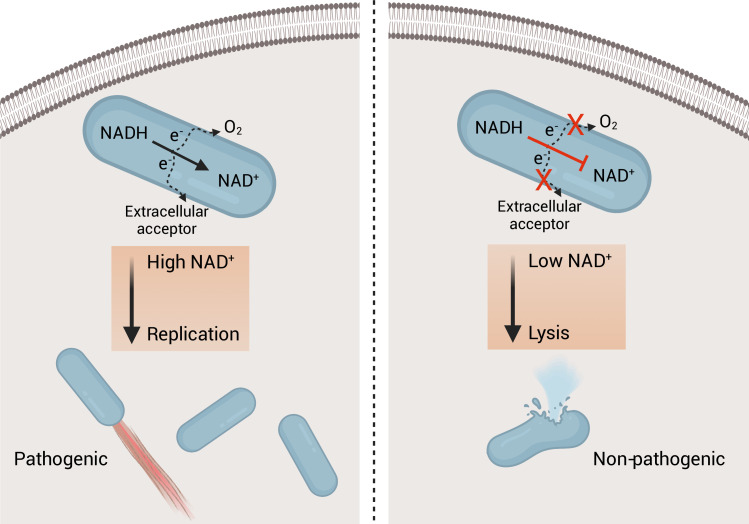

Using a previously described luciferase-based assay to quantify cytosolic plasmid release, we confirmed that the ΔmenB strain exhibited increased intracellular bacteriolysis (Figure 5D; Sauer et al., 2010). We further found that NOX expression rescued ΔmenB bacteriolysis, but not a comparable bacteriolysis phenotype in a ΔglmR strain that was previously shown to result from unrelated deficiencies in cell wall biosynthesis (Figure 5D; Pensinger et al., 2021). These studies thus show that efficient NAD+ regeneration is essential for limiting cytosolic bacteriolysis and suggest a model whereby respiration-mediated NAD+ regeneration promotes virulence, in part, by maintaining cell viability and facilitating evasion of innate immunity (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Model of the role of respiration in L. monocytogenes pathogenesis.

On the left, an intracellular bacterium with the ability to oxidize NADH and transfer electrons through the aerobic and extracellular electron transfer electron transport chains can regenerate and maintain high NAD+ levels allowing the bacterium to grow and be virulent. On the right, an intracellular bacterium unable to regenerate NAD+, by lacking the electron transport chains, is avirulent because it lyses in the cytosol of infected cells.

Discussion

Cellular respiration is one of the most fundamental aspects of bacterial metabolism and a validated antibiotic target. Despite its importance, the role of cellular respiration in systemic bacterial pathogenesis has remained largely unexplained. The studies reported here address the basis of respiration in the pathogen L. monocytogenes, identifying two electron transport chains that are partially functionally redundant and essential for pathogenesis. We find that restoring NAD+ regeneration to respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains through the heterologous expression of NOX prevents bacteriolysis within the host cytosol and rescues pathogenesis. These findings thus support the conclusion that NAD+ regeneration represents a major role of L. monocytogenes respiration during pathogenesis.

Our results clarify several aspects of the basis and significance of energy metabolism in L. monocytogenes. In particular, our studies establish the relationship between L. monocytogenes’ two electron transport chains – confirming previous observations that flavin-based electron transfer enhances anaerobic L. monocytogenes growth and revealing a novel aerobic function of this pathway (Light et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2021). While the benefit of flavin-based electron transfer was only apparent in the absence of aerobic respiration, identifying the substrates and functions of aerobic activation of this pathway may provide an interesting avenue for future studies.

Our studies further reveal that L. monocytogenes employs a respiro-fermentative metabolic strategy characterized by production of the reduced fermentation products lactate and ethanol in the absence of an electron acceptor and acetate when a respiratory pathway is activated. This respiro-fermentative metabolism is consistent with the proton motive force being less central to L. monocytogenes energy metabolism and with a primary role of respiration being to unleash ATP production via acetate kinase catalyzed substrate-level phosphorylation (Figure 1D).

The importance of cellular respiration for non-proton motive force-related processes is further supported by observations about the ability of heterologous NOX overexpression to rescue the severe pathogenesis phenotypes of respiration-deficient L. monocytogenes strains. NOX expression fully rescued in vitro growth defects and partially rescued virulence in the mouse model of disease, suggesting that NAD+ regeneration represents the sole function of respiration in some cell types and a major (but not sole) function of respiration in systemic disease. These findings suggest that a presently unaccounted for proton motive force-dependent aspect of microbial physiology is likely important for systemic disease. Considering the significance of cellular respiration as an antibiotic target, these insights into the role respiration be relevant for future drug development strategies.

While our studies provide evidence that NAD+ regeneration is critical for preventing intracellular bacteriolysis, some ambiguity remains regarding the molecular mechanism linking NAD+/NADH imbalance to the loss of L. monocytogenes virulence. One potential clue comes from a recent study of the transcriptional regulator Rex. Rex senses a low NAD+/NADH ratio and derepresses reductive fermentation pathways, including those that produce lactate and ethanol, and a L. monocytogenes strain deficient in Rex exhibited decreased virulence (Halsey et al., 2021). Activation of part of the Rex regulon may at least partially account for the NAD+/NADH-dependent phenotypes observed in our studies. The centrality of NAD+ regeneration to L. monocytogenes also falls in line with relatively recent studies of mammalian respiration. Several studies have shown that the inability of respiration-deficient mammalian cells to regenerate NAD+ impacts anabolic metabolisms and inhibits growth (Birsoy et al., 2015; Li et al., 2020; Sullivan et al., 2015; Titov et al., 2016). Our discovery of a similar role of respiration in a bacterial pathogen thus suggests that the importance of respiration for NAD+ regeneration is a fundamental property conserved across the kingdoms of life.

Materials and methods

Bacterial culture and strains

All strains of L. monocytogenes used in this study were derived from the wildtype 10403S (streptomycin-resistant) strain (see Table 1 for references and additional details). The L. lactis water-forming nox (NCBI accession WP_010905313.1) was cloned into the pPL2 vector downstream of the constitutive Phyper promoter and integrated into the L. monocytogenes genome via conjugation, as previously described (Lauer et al., 2002; Shen and Higgins, 2005). The ΔQC/fmnB strain was generated from ΔQC and fmnB::tn strains using generalized transduction protocols with phage U153, as previously described (Hodgson, 2000; Reniere et al., 2016).

Table 1. Bacterial strains used in this study.

| Strains | Strain number | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Listeria monocytogenes (wildtype) | 10403S | Bécavin et al., 2014 |

| ΔcydAB/ΔqoxA | DP-L6624 | Chen et al., 2017 |

| ΔcydAB/ΔqoxA/fmnB::tn | DP-L7190 | This study |

| ΔfmnB | DP-L7195 | This study |

| Wildtype + pPL2 NOX | DP-L7188 | This study |

| ΔcydAB/ΔqoxA + pPL2 NOX | DP-L7189 | This study |

| ΔcydAB/ΔqoxA/fmnB::tn + pPL2 NOX | DP-L7191 | This study |

| ΔflaA | DP-L5986 | Nguyen et al., 2020 |

| Δndh1/ndh2::tn | DP-L6626 | This study |

| Δndh1/ndh2::tn + pPL2 NOX | DP-L7253 | This study |

| Wildtype + pBHE573 | JDS18 | Sauer et al., 2010 |

| Wildtype + pPL2 NOX + pBHE573 | JDS2328 | This study |

| ΔmenB + pBHE573 | JDS1191 | Chen et al., 2017 |

| ΔmenB + pPL2 NOX + pBHE573 | JDS2333 | This study |

| Δhly + pBHE573 | JDS19 | Sauer et al., 2010 |

| ΔglmR + pBHE573 | JDS21 | Sauer et al., 2010 |

| ΔglmR + pPL2 NOX + pBHE573 | JDS2329 | This study |

| Escherichia coli | SM10 | |

| pPL2-NOX | DP-E7206 | This study |

| pBHE573 | JDS17 | Sauer et al., 2010 |

L. monocytogenes cells were grown at 37°C in filter-sterilized BHI media. Growth curves were spectrophotometrically measured by optical density at a wavelength of 600 nm (OD600). An anaerobic chamber (Coy Laboratory Products) with an environment of 2% H2 balanced in N2 was used for anaerobic experiments. Media was supplemented with 50 mM ferric ammonium citrate or 50 mM fumarate for experiments that addressed the effect of electron acceptors on L. monocytogenes growth.

Plaque assays

L. monocytogenes strains were grown overnight slanted at 30°C and were diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Six-well plates containing 1.2 × 106 mouse L2 fibroblast cells per well were infected with the L. monocytogenes strains at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 0.1. At 1-hour post-infection, the L2 cells were washed with PBS and overlaid with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 0.7% agarose and gentamicin (10 µg/mL) to kill extracellular bacteria, and then plates were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. At 72-hour post-infection, L2 cells were overlaid with a staining mixture containing DMEM, 0.7% agarose, neutral red (Sigma), and gentamicin (10 µg/mL), and plaques were scanned and analyzed using ImageJ, as previously described (Reniere et al., 2016; Sun et al., 1990).

Intracellular macrophage growth curves

L. monocytogenes strains were grown overnight slanted at 30°C and were diluted in sterile PBS. A total of 3 × 106 BMMs from C57BL/6 mice were seeded in 60 mm non-TC treated dishes containing 14 12 mm glass coverslips in each dish and infected at an MOI of 0.25 as previously described (Portnoy et al., 1988; Reniere et al., 2016).

Mouse virulence experiments

L. monocytogenes strains were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. to mid-logarithmic phase. Bacteria were collected and washed in PBS and resuspended at a concentration of 5 × 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per 200 μL of sterile PBS. The 8-week-old female CD-1 mice (Charles River) were then injected with 1 × 105 CFU via the tail vein. At 48 hours post-infection, spleens and livers were collected, homogenized, and plated to determine the number of CFU per organ.

NAD+/NADH assay

L. monocytogenes strains were grown at 37°C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. to mid-logarithmic phase. Cultures were centrifuged and then resuspended in PBS. Resuspended bacteria were then lysed by vortexing with 0.1-mm-diameter zirconia–silica beads for 10 min. Lysates were used to measure NAD+ and NADH levels using the NAD/NADH-Glo assay (Promega, G9071) by following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Fermentation product measurements

Organic acids and ethanol were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (Agilent, 1260 Infinity), using a standard analytical system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with an Aminex Organic Acid Analysis column (Bio-Rad, HPX-87H 300 × 7.8 mm) heated at 60°C. The eluent was 5 mM of sulfuric acid, used at a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. We used a refractive index detector 1260 Infinity II RID and a 1260 Infinity II variable wavelength detector. A five-point calibration curve based on peak area was generated and used to calculate concentrations in the unknown samples.

Motility assay

L. monocytogenes strains were grown overnight slanted at 30°C and were diluted in sterile PBS. Cultures were normalized to an OD600 of 1.0 and 1 μL of cultures were inoculated on semisolid BHI 0.3% agar. Mutant swarming diameters relative to wildtype were quantified following 48 hours incubation at 30°C.

Intracellular bacteriolysis assay

Bacteriolysis assays were performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2017). Briefly, immortalized Ifnar-/- macrophages were plated at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per well in a 24-well plate. Cultures of L. monocytogenes strains were grown overnight slanted at 30°C and diluted to a final concentration of 5 × 108 CFU per mL. Diluted cultures were then used to infect macrophages at an MOI of 10. At 1-hour post-infection, wells were aspirated, and the media was replaced with media containing 50 μg/mL gentamicin. At 6 hours post-infection, media was aspirated, and macrophages were lysed using TNT lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, 1% Triton [pH 8.0]). Lysate was then transferred to 96-well plates and assayed for luciferase activity by luminometry (Synergy HT; BioTek, Winooski, VT).

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (T32GM007215 to HBS, R01AI137070 to J-DS, R01AI073843 to EPS, 1P01AI063302, and 1R01AI27655 to DAP, and K22AI144031 to SHL), the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (Ford Foundation Fellowship to RR-L), the University of California Dissertation-Year Fellowship (to RR-L), and the Searle Scholars Program (to SHL). VMRR holds a Postdoctoral Enrichment Program Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund and acknowledges support from the Academic Pathways Postdoctoral Fellowship at Vanderbilt University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna H Gray Fellows Program. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Contributor Information

Samuel H Light, Email: samlight@uchicago.edu.

Sophie Helaine, Harvard Medical School, United States.

Gisela Storz, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, United States.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

National Institutes of Health T32GM007215 to Hans B Smith.

National Institutes of Health R01AI137070 to John Demian Sauer.

National Institutes of Health R01AI073843 to Eric P Skaar.

National Institutes of Health 1P01AI063302 to Daniel A Portnoy.

National Institutes of Health 1R01AI27655 to Daniel A Portnoy.

National Institutes of Health K22AI144031 to Samuel H Light.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Ford Foundation Fellowship to Rafael Rivera-Lugo.

University of California Dissertation-Year Fellowship to Rafael Rivera-Lugo.

Kinship Foundation Searle Scholars Program to Samuel H Light.

Howard Hughes Medical Institute Hanna H. Gray Fellows Program to Valeria M Reyes Ruiz.

Burroughs Wellcome Fund Postdoctoral Enrichment Program to Valeria M Reyes Ruiz.

Vanderbilt University Academic Pathways Postdoctoral Fellowship to Valeria M Reyes Ruiz.

Department of Energy DE-AC02-05CH11231 to Sara Tejedor-Sanz, Caroline M Ajo-Franklin.

Additional information

Competing interests

No competing interests declared.

No competing interests declared.

is a co-inventor on a filed patent describing the use of NOX. (US Patent App. 15/749,218).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Conceptualization, Investigation.

Investigation.

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Investigation.

Investigation.

Investigation.

Conceptualization, Investigation.

Investigation.

Investigation.

Investigation.

Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft.

Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft.

Ethics

All animal work was performed in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Berkeley (AUP 2016-05-8811).

Additional files

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files.

References

- Ali MM, Newsom DL, González JF, Sabag-Daigle A, Stahl C, Steidley B, Dubena J, Dyszel JL, Smith JN, Dieye Y, Arsenescu R, Boyaka PN, Krakowka S, Romeo T, Behrman EJ, White P, Ahmer BMM. Fructose-asparagine is a primary nutrient during growth of Salmonella in the inflamed intestine. PLOS Pathogens. 2014;10:e1004209. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bader M, Muse W, Ballou DP, Gassner C, Bardwell JC. Oxidative protein folding is driven by the electron transport system. Cell. 1999;98:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bécavin C, Bouchier C, Lechat P, Archambaud C, Creno S, Gouin E, Wu Z, Kühbacher A, Brisse S, Pucciarelli MG, García-del Portillo F, Hain T, Portnoy DA, Chakraborty T, Lecuit M, Pizarro-Cerdá J, Moszer I, Bierne H, Cossart P. Comparison of widely used Listeria monocytogenes strains EGD, 10403S, and EGD-e highlights genomic variations underlying differences in pathogenicity. MBio. 2014;5:e00969-14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00969-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birsoy K, Wang T, Chen WW, Freinkman E, Abu-Remaileh M, Sabatini DM. An Essential Role of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain in Cell Proliferation Is to Enable Aspartate Synthesis. Cell. 2015;162:540–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, McDougal CE, D’Antonio MA, Portman JL, Sauer JD. A Genetic Screen Reveals that Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-Naphthoate (DHNA), but Not Full-Length Menaquinone, Is Required for Listeria monocytogenes Cytosolic Survival. mBio. 2017;8:e00119-17. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00119-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G.Y, Kao CY, Smith HB, Rust DP, Powers ZM, Li AY, Sauer JD. Mutation of the Transcriptional Regulator YtoI Rescues Listeria monocytogenes Mutants Deficient in the Essential Shared Metabolite 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-Naphthoate (DHNA. Infection and Immunity. 2019;88:e00366-19. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00366-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins MD, Jones D. Distribution of isoprenoid quinone structural types in bacteria and their taxonomic implication. Microbiological Reviews. 1981;45:316–354. doi: 10.1128/mr.45.2.316-354.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GM, Greening C, Hards K, Berney M. Energetics of pathogenic bacteria and opportunities for drug development. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 2014;65:1–62. doi: 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett D, Goldrick M, Fernandes VE, Davidge K, Poole RK, Andrew PW, Cavet J, Roberts IS. Listeria monocytogenes Has Both Cytochrome bd-Type and Cytochrome aa 3-Type Terminal Oxidases, Which Allow Growth at Different Oxygen Levels, and Both Are Important in Infection. Infection and Immunity. 2017;85:e00354-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00354-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig M, Sadik AY, Golubeva YA, Tidhar A, Slauch JM. Twin-arginine translocation system (tat) mutants of Salmonella are attenuated due to envelope defects, not respiratory defects. Molecular Microbiology. 2013;89:887–902. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen AJ, Rosen BP, Konings WN. Diversity of transport mechanisms: common structural principles. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2000;25:397–401. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen AJM, Nouwen N. Protein translocation across the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2008;77:643–667. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.160747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duwat P, Sourice S, Cesselin B, Lamberet G, Vido K, Gaudu P, Le Loir Y, Violet F, Loubière P, Gruss A. Respiration capacity of the fermenting bacterium Lactococcus lactis and its positive effects on growth and survival. Journal of Bacteriology. 2001;183:4509–4516. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.15.4509-4516.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber F, Thiennimitr P, Spiga L, Byndloss MX, Litvak Y, Lawhon S, Andrews-Polymenis HL, Winter SE, Bäumler AJ. Respiration of Microbiota-Derived 1,2-propanediol Drives Salmonella Expansion during Colitis. PLOS Pathogens. 2017;13:e1006129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. Listeria monocytogenes - from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 2009;7:623–628. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis CC, Hughes ER, Spiga L, Winter MG, Zhu W, Furtado de Carvalho T, Chanin RB, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV, Santos RL, Winter SE. Dysbiosis-Associated Change in Host Metabolism Generates Lactate to Support Salmonella Growth. Cell Host & Microbe. 2018;23:570. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halsey CR, Glover RC, Thomason MK, Reniere ML. The redox-responsive transcriptional regulator Rex represses fermentative metabolism and is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. PLOS Pathogens. 2021;17:e379. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer ND, Reniere ML, Cassat JE, Zhang Y, Hirsch AO, Indriati Hood M, Skaar EP. Two Heme-Dependent Terminal Oxidases Power Staphylococcus aureus Organ-Specific Colonization of the Vertebrate Host. MBio. 2013;1:e13. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00241-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenoehrl EJ, Wiggins TJ, Berney M. Bioenergetic Inhibitors: Antibiotic Efficacy and Mechanisms of Action in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2020;10:611683. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2020.611683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heux S, Cachon R, Dequin S. Cofactor engineering in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Expression of a H2O-forming NADH oxidase and impact on redox metabolism. Metabolic Engineering. 2006;8:303–314. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson DA. Generalized transduction of serotype 1/2 and serotype 4b strains of Listeria monocytogenes. Molecular Microbiology. 2000;35:312–323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KA, Flynn JM, Naranjo B, Shikhare ID, Gralnick JA. Substrate-level phosphorylation is the primary source of energy conservation during anaerobic respiration of Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1. Journal of Bacteriology. 2010;192:3345–3351. doi: 10.1128/JB.00090-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones-Carson J, Husain M, Liu L, Orlicky DJ, Vázquez-Torres A. Cytochrome bd-Dependent Bioenergetics and Antinitrosative Defenses in Salmonella Pathogenesis. MBio. 2016;1:e16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02052-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer P, Chow MYN, Loessner MJ, Portnoy DA, Calendar R. Construction, characterization, and use of two Listeria monocytogenes site-specific phage integration vectors. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184:4177–4186. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.15.4177-4186.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lencina AM, Franza T, Sullivan MJ, Ulett GC, Ipe DS, Gaudu P, Gennis RB, Schurig-Briccio LA. Type 2 NADH Dehydrogenase Is the Only Point of Entry for Electrons into the Streptococcus agalactiae Respiratory Chain and Is a Potential Drug Target. MBio. 2018;1:e18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01034-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin GR, Stacy A, Michie KL, Lamont RJ, Whiteley M. Large-scale identification of pathogen essential genes during coinfection with sympatric and allopatric microbes. PNAS. 2019;116:19685–19694. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1907619116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ji BW, Dixit PD, Lien EC, Tchourine K, Hosios AM, Abbott KL, Westermark AM, Gorodetsky EF, Sullivan LB, Vander Heiden MG, Vitkup D. Cancer cells depend on environmental lipids for proliferation when electron acceptors are limited. Cancer Biology. 2020;1:e90. doi: 10.1101/2020.06.08.134890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light S.H, Su L, Rivera-Lugo R, Cornejo JA, Louie A, Iavarone AT, Ajo-Franklin CM, Portnoy DA. A flavin-based extracellular electron transfer mechanism in diverse Gram-positive bacteria. Nature. 2018;562:140–144. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0498-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light SH, Méheust R, Ferrell JL, Cho J, Deng D, Agostoni M, Iavarone AT, Banfield JF, D’Orazio SEF, Portnoy DA. Extracellular electron transfer powers flavinylated extracellular reductases in Gram-positive bacteria. PNAS. 2019;116:26892–26899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915678116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de Felipe F, Kleerebezem M, de Vos WM, Hugenholtz J. Cofactor engineering: a novel approach to metabolic engineering in Lactococcus lactis by controlled expression of NADH oxidase. Journal of Bacteriology. 1998;180:3804–3808. doi: 10.1128/JB.180.15.3804-3808.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manson MD, Tedesco P, Berg HC, Harold FM, Van der Drift C. A protonmotive force drives bacterial flagella. PNAS. 1977;74:3060–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méheust R, Huang S, Rivera-Lugo R, Banfield JF, Light SH. Post-translational flavinylation is associated with diverse extracytosolic redox functionalities throughout bacterial life. eLife. 2021;10:e66878. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Ramos A, Costa H, van Swam II, Hugenholtz J, Kleerebezem M, de Vos W, Santos H. Effect of different NADH oxidase levels on glucose metabolism by Lactococcus lactis: kinetics of intracellular metabolite pools determined by in vivo nuclear magnetic resonance. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2002a;68:6332–6342. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6332-6342.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves AR, Ventura R, Mansour N, Shearman C, Gasson MJ, Maycock C, Ramos A, Santos H. Is the Glycolytic Flux in Lactococcus lactisPrimarily Controlled by the Redox Charge? Journal OF Biological Chemistry. 2002b;277:28088–28098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen BN, Chávez-Arroyo A, Cheng MI, Krasilnikov M, Louie A, Portnoy DA. TLR2 and endosomal TLR-mediated secretion of IL-10 and immune suppression in response to phagosome-confined Listeria monocytogenes. PLOS Pathogens. 2020;16:e1008622. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen MB, Gaudu P, Lechardeur D, Petit MA, Gruss A. Aerobic respiration metabolism in lactic acid bacteria and uses in biotechnology. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 2012;3:37–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pensinger DA, Gutierrez KV, Smith HB, Vincent WJB, Stevenson DS, Black KA, Perez-Medina KM, Dillard JP, Rhee KY, Amador-Noguez D, Huynh TN, Sauer JD. Listeria Monocytogenes GlmR Is an Accessory Uridyltransferase Essential for Cytosolic Survival and Virulence. Microbiology. 2021;1:e6214. doi: 10.1101/2021.10.27.466214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reniere ML, Whiteley AT, Portnoy DA. An In Vivo Selection Identifies Listeria monocytogenes Genes Required to Sense the Intracellular Environment and Activate Virulence Factor Expression. PLOS Pathogens. 2016;12:e41. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson AR, Libby SJ, Fang FC. A nitric oxide-inducible lactate dehydrogenase enables Staphylococcus aureus to resist innate immunity. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2008;319:1672–1676. doi: 10.1126/science.1155207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Chávez F, Zhang LF, Faber F, Lopez CA, Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Xu G, Velazquez EM, Lebrilla CB, Winter SE, Bäumler AJ. Depletion of Butyrate-Producing Clostridia from the Gut Microbiota Drives an Aerobic Luminal Expansion of Salmonella. Cell Host & Microbe. 2016;19:443–454. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romick TL, Fleming HP, McFeeters RF. Aerobic and anaerobic metabolism of Listeria monocytogenes in defined glucose medium. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1996;62:304–307. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.1.304-307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer JD, Witte CE, Zemansky J, Hanson B, Lauer P, Portnoy DA. Listeria monocytogenes triggers AIM2-mediated pyroptosis upon infrequent bacteriolysis in the macrophage cytosol. Cell Host & Microbe. 2010;7:412–419. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen A, Higgins DE. The 5’ untranslated region-mediated enhancement of intracellular listeriolysin O production is required for Listeria monocytogenes pathogenicity. Molecular Microbiology. 2005;57:1460–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slonczewski JL, Fujisawa M, Dopson M, Krulwich TA. Cytoplasmic pH measurement and homeostasis in bacteria and archaea. Advances in Microbial Physiology. 2009;55:317. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(09)05501-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HB, Li TL, Liao MK, Chen GY, Guo Z, Sauer JD. Listeria monocytogenes MenI Encodes a DHNA-CoA Thioesterase Necessary for Menaquinone Biosynthesis, Cytosolic Survival, and Virulence. Infection and Immunity. 2021;89:e00792-20. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00792-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiga L, Winter MG, Furtado de Carvalho T, Zhu W, Hughes ER, Gillis CC, Behrendt CL, Kim J, Chessa D, Andrews-Polymenis HL, Beiting DP, Santos RL, Hooper LV, Winter SE. An Oxidative Central Metabolism Enables Salmonella to Utilize Microbiota-Derived Succinate. Cell Host & Microbe. 2017;22:291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stritzker J, Janda J, Schoen C, Taupp M, Pilgrim S, Gentschev I, Schreier P, Geginat G, Goebel W. Growth, virulence, and immunogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes aro mutants. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:5622–5629. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5622-5629.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LB, Gui DY, Hosios AM, Bush LN, Freinkman E, Vander Heiden MG. Supporting Aspartate Biosynthesis Is an Essential Function of Respiration in Proliferating Cells. Cell. 2015;162:552–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun AN, Camilli A, Portnoy DA. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infection and Immunity. 1990;58:3770–3778. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3770-3778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiennimitr P, Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Tolstikov V, Huseby DL, Sterzenbach T, Tsolis RM, Roth JR, Bäumler AJ. Intestinal inflammation allows Salmonella to use ethanolamine to compete with the microbiota. PNAS. 2011;108:17480–17485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107857108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titov DV, Cracan V, Goodman RP, Peng J, Grabarek Z, Mootha VK. Complementation of mitochondrial electron transport chain by manipulation of the NAD+/NADH ratio. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2016;352:231–235. doi: 10.1126/science.aad4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay PL, Zhang T, Dar SA, Leang C, Lovley DR, Newman DK. The Rnf Complex of Clostridium ljungdahlii Is a Proton-Translocating Ferredoxin:NAD+ Oxidoreductase Essential for Autotrophic Growth. MBio. 2013;1:e12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00406-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trivett TL, Meyer EA. Citrate cycle and related metabolism of Listeria monocytogenes. Journal of Bacteriology. 1971;107:770–779. doi: 10.1128/jb.107.3.770-779.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilharm G, Lehmann V, Krauss K, Lehnert B, Richter S, Ruckdeschel K, Heesemann J, Trülzsch K. Yersinia enterocolitica type III secretion depends on the proton motive force but not on the flagellar motor components MotA and MotB. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72:4004–4009. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.7.4004-4009.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SE, Thiennimitr P, Winter MG, Butler BP, Huseby DL, Crawford RW, Russell JM, Bevins CL, Adams LG, Tsolis RM, Roth JR, Bäumler AJ. Gut inflammation provides a respiratory electron acceptor for Salmonella. Nature. 2010;467:426–429. doi: 10.1038/nature09415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter SE, Winter MG, Xavier MN, Thiennimitr P, Poon V, Keestra AM, Laughlin RC, Gomez G, Wu J, Lawhon SD, Popova IE, Parikh SJ, Adams LG, Tsolis RM, Stewart VJ, Bäumler AJ. Host-derived nitrate boosts growth of E. coli in the inflamed gut. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2013;339:708–711. doi: 10.1126/science.1232467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Z, Boeren S, Bhandula V, Light SH, Smid EJ, Notebaart RA, Abee T. Bacterial Microcompartments Coupled with Extracellular Electron Transfer Drive the Anaerobic Utilization of Ethanolamine in Listeria monocytogenes. MSystems. 2021;6:e20. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.01349-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]