Abstract

Thiobacillus ferrooxidans is one of the chemolithoautotrophic bacteria important in industrial biomining operations. During the process of ore bioleaching, the microorganisms are subjected to several stressing conditions, including the lack of some essential nutrients, which can affect the rates and yields of bioleaching. When T. ferrooxidans is starved for phosphate, the cells respond by inducing the synthesis of several proteins, some of which are outer membrane proteins of high molecular weight (70,000 to 80,000). These proteins were considered to be potential markers of the phosphate starvation state of these microorganisms. We developed a single-cell immunofluorescence assay that allowed monitoring of the phosphate starvation condition of this biomining microorganism by measuring the increased expression of the surface proteins. In the presence of low levels of arsenate (2 mM), the growth of phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans cells was greatly inhibited compared to that of control nonstarved cells. Therefore, the determination of the phosphorus nutritional state is particularly relevant when arsenic compounds are solubilized during the bioleaching of different ores.

Thiobacillus ferrooxidans has an important role in the bioleaching of ores (13, 23). During this process, the bacteria are subjected to several stressing conditions, such as temperature changes (7, 21, 25), pH variations (1), or the lack of some essential nutrients (10, 19, 20). The lack of phosphorus may be a stressing condition for the microorganisms that can affect the bioleaching of minerals (10, 16, 19, 20). In addition, the availability of phosphorus in bioleaching environments can be a limiting factor for bacterial growth (23).

When T. ferrooxidans and other biomining microorganisms encounter phosphate limitation, they respond with a global change in the expression of several proteins (10, 16, 19, 20). Some of these proteins are localized in the outer membrane, and their increased expression seems to be characteristic of that physiological starvation condition (10, 19). Therefore, as we have suggested previously (8), it should be possible by measuring the levels of synthesis of these proteins to monitor in situ the phosphate starvation state of the bacteria in a given bioleaching operation. The chemical analysis of ores does not indicate the bioavailability of phosphate to the bacterium, since this compound may be present in the ore but in an insoluble or precipitated form that is not readily available to the microorganism. Therefore, an assay like the one proposed here would be essential for monitoring the physiological state of the bacteria under such conditions.

The purpose of this study was to develop an immunological method for following the phosphate limitation condition in individual cells of T. ferrooxidans. It is expected that by assessing the relative physiological condition of the bacteria in a bioleaching operation, decisions could then be made as to whether, if possible, the conditions should be changed to improve the local bacterial activity and thus the efficiency of the bioleaching process.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms used in this study were T. ferrooxidans R2 (1) and ATCC 19859. They were both grown at 30°C and at pH 1.5 in a modified medium that contained 0.04 g of K2HPO4, 33.3 g of FeSO4 · 7H2O, 0.4 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.1 g of (NH4)2SO4 per liter and no trace metals, as described previously (1, 4). Leptospirillum ferrooxidans DSM 2705 and Thiobacillus thiooxidans DSM 504 were grown as described before (4, 9). The growth of all of these microorganisms under phosphate-limiting conditions was in the same medium, except that the phosphate salt was omitted in each case (20).

SDS-PAGE and two-dimensional PAGE analysis.

Total cell proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) according to the Laemmli procedure (11) as described previously (19). To separate the total cell proteins by two-dimensional PAGE with nonequilibrium pH gradient (NEPHGE), we used ampholites (pH 3 to 10) from Bio-Rad Laboratories as described before (1, 15, 20). The cell samples (3.5 mg, wet weight) were resuspended in 100 μl of sonication buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 5mM MgCl2, and 50 μg of pancreatic RNase per ml), sonicated, and treated with DNase (50 μg/ml, final concentration). The mixture was then lyophilized and dissolved in lysis buffer as described previously (1, 15, 20). Molecular mass standards for the second dimension were from Bio-Rad Laboratories.

Purification of proteins from two-dimensional gels and production of antiserum.

Two protein spots present in phosphate-starved cells of T. ferrooxidans were cut out from Coomassie Blue-stained two-dimensional gels with a scalpel (see Fig. 1). The mixture of both proteins was designated P2. To increase the mass of each protein spot, thicker two-dimensional gels (5 mm) were run, which allowed us to load approximately fivefold more of the sample in each run. The antiserum against P2 was made by subcutaneous immunizations of New Zealand rabbits, in different sites each time, with approximately 50 μg of the protein mixture per injection (this corresponded to ca. two to four thick two-dimensional gel pieces containing the P2 proteins). The gel pieces containing the proteins were smashed and mixed (1:1) with Freund’s incomplete adjuvant by forcing the mixture through the needle of a disposable plastic syringe. Immunization was done four times at 2-week intervals. At 2 weeks after the fourth immunization blood was collected from the rabbits. Serum was obtained by centrifugation, and the antibodies were purified and concentrated by affinity chromatography on protein A-Sepharose columns.

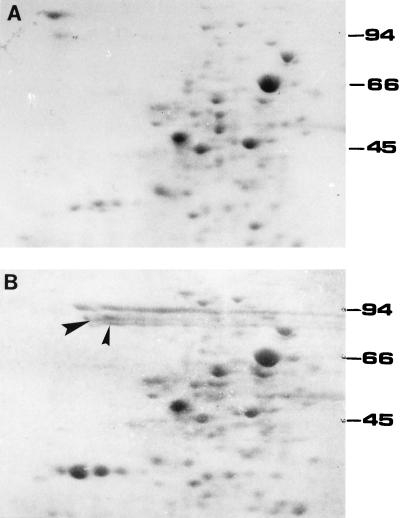

FIG. 1.

Two-dimensional PAGE analysis of proteins synthesized by T. ferrooxidans under phosphate starvation conditions. Total proteins from T. ferrooxidans grown in the presence (A) or absence (B) of phosphate were analyzed by NEPHGE (pH 3 to 10) followed by Coomassie Blue staining. Only a portion of the gels is shown. The acidic side of the isoelectrofocusing gel is on the right. The arrowheads in panel B show the protein bands (including some of the smearing) that were cut from the gel to obtain P2. Numbers to the right are the molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons).

N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis.

Proteins of interest were recovered from Coomassie Blue-stained and heat-dried two-dimensional gels by excising the protein spots. After rehydration and concentration of the spots by SDS-PAGE, the proteins were electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (5) and subjected to microsequencing by the Center for the Synthesis and Analysis of Biomolecules at the University of Chile, Santiago, Chile.

Western immunoblotting and dot immunoassay.

We used a dot immunoassay to estimate the reaction of the polyclonal antiserum to P2 with whole cells of T. ferrooxidans, L. ferrooxidans, and T. thiooxidans. This assay was similar to our previously reported dot immunoassays (2, 4, 8, 9), except that the antiserum prepared against P2 was used as the primary antibody (1:1,000 dilution) and that immunoglobulin conjugated with peroxidase was used as the secondary antibody. In some experiments, the development of the antigen-antibody reaction was done by using the ECL chemiluminescence system from Amersham Life Science, with rabbit immunoglobulin horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody (from a donkey) as a second antibody. The conditions for the antigen-antibody reactions and for detecting the light emission by exposure to X-ray film were as described by the manufacturers. For Western immunoblotting, the proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were electrotransferred to a nitrocellulose membrane as described by Towbin et al. (22) with the Trans-Blot Cell system (Bio-Rad) in transfer buffer and an application of a 600-mA constant current for 48 min. The same antibodies and development system with peroxidase were used to treat the nitrocellulose membrane containing the transferred proteins.

Single-cell immunofluorescence assay.

Whole-cell immunofluorescence assays were performed with glass slides. T. ferrooxidans cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 20 min and were washed three times by centrifugation with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 25 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4], 125 mM NaCl). To fix the microorganisms, bacterial cell suspensions (5 μl) were transferred to glass slides placed on a flat surface and then allowed to air dry. The cells were then fixed by adding cold methanol and allowing them to air dry for 5 min. The slides were immunostained with the primary antiserum (against P2 proteins) diluted 1:100 in PBS and incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a humid chamber. After the samples were washed in PBS, the second antibody (diluted 1:80) was added, a fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (F-0257, titer 1:40; Sigma Immunochemicals); the samples were then incubated for 1 h at 37°C in the humid chamber. After the samples were again washed in PBS, the cells were covered with a drop of 50% glycerol in PBS and then observed under an Olympus BX50 fluorescence microscope fitted with a U-MNB filter block (excitation, 470 to 490 nm; 515-nm barrier filter). Controls with preimmune rabbit antiserum were also observed.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have previously reported that phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans cells increase the expression of several proteins which are absent or present in very low amounts in control cells (20). An example of these changes, in which the total cell proteins were separated by two-dimensional PAGE, is shown in Fig. 1. The arrowheads in Fig. 1B indicate two spots with molecular masses ranging from 70 to 80 kDa which are localized in the outer membrane fraction of T. ferrooxidans (10, 19). Since these proteins are induced during phosphate limitation and are characteristic of the response, we thought of using them as a potential diagnostic marker for the phosphorus status of T. ferrooxidans. The two outer membrane proteins were cut out together from the gels and were designated P2. These protein spots usually gave a smear under these separation conditions (19), a result apparently due to posttranslational modifications. In this regard, when these spots were subjected to N-terminal-end microsequencing, the results clearly indicated a blocked N terminus (data not shown).

The P2 proteins were used as antigens to prepare polyclonal antibodies. To test for the specificity of these antibodies, we employed a dot immunoassay (DIMA) with the P2 antiserum and developed it colorimetrically (Fig. 2A). Phosphate-starved cells (lane 2) gave a very strong reaction compared to the control cells (lane 1), thus demonstrating that the antibodies were specific for phosphate-starved cells.

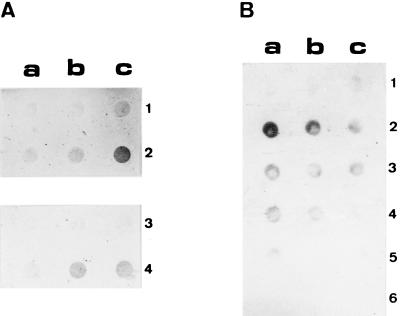

FIG. 2.

Dot immunoassay of several biomining microorganisms with a polyclonal antiserum to outer membrane P2 proteins from T. ferrooxidans. (A) T. ferrooxidans control cells (lanes 1 and 3) or phosphate-starved cells (lanes 2 and 4) were treated (lanes 3 and 4) to remove part of their LPS or not treated (lanes 1 and 2) and were then applied to a nitrocellulose membrane in the following numbers: 105 (a), 106 (b), and 107 (c) cells. After the bacteria were fixed, they were reacted with antiserum to the P2 proteins and developed with a secondary antibody conjugated with peroxidase as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Control cells (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or phosphate-starved cells (lanes 2, 4, and 6) of T. ferrooxidans (lanes 1 and 2), L. ferrooxidans (lanes 3 and 4), and T. thiooxidans (lanes 5 and 6) were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane in the following numbers: 106 (a), 105 (b), and 104 (c) cells. The fixing and reaction with the first antibody were done as described in panel A, except that development was done with a secondary antibody and a chemiluminescent reaction as described in Materials and Methods.

It has been shown that the O antigen in lipopolysaccharides (LPS) can shield outer membrane proteins (24, 26). We have shown that when T. ferrooxidans cells are treated to remove about 50% of their LPS, there is an increase of reactivity of the outer membrane protein Omp40 with an antiserum against this protein (3). To find out whether P2 proteins showed surface-exposed epitopes in the phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans cells and whether their reaction was masked by the presence of LPS, we subjected both control and phosphate-starved cells to the LPS extraction procedure (3) and assayed them by DIMA with antiserum to P2. Figure 2A, lanes 3 and 4, shows that prior removal of the LPS did not increase the reaction with the antiserum, suggesting that the outer membrane P2 proteins are exposed in the surface of the phosphate-starved microorganisms and that LPS does not prevent the antigen-antibody reaction. Furthermore, there was a slight decrease in the intensity of the reaction with the antibodies in both control and phosphate-starved cells that were previously treated to remove part of their LPS (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4, respectively). Under these conditions, the specificity of the antiserum for the phosphate-starved cells was also clearly visible.

To determine the specificity of the antiserum to P2 for different biomining microorganisms, we used a DIMA assay and chemiluminescence with T. ferrooxidans, T. thiooxidans, and L. ferrooxidans cells (Fig. 2B). Under these conditions, the P2 antiserum also reacted with a much greater intensity with the T. ferrooxidans cells starved for phosphate (lane 2) compared to the control cells (lane 1). L. ferrooxidans gave some faint reaction when either control (lane 3) or phosphate-starved (lane 4) cells were used; this was apparently due to a nonspecific interaction, since there was no great difference in reaction when different numbers of cells were used (lanes 3 and 4, Fig. 2B). When T. thiooxidans control (lane 5) or phosphate-starved (lane 6) cells were tested, almost no reaction was observed. These results indicate not only that the P2 antiserum distinguishes starved from nonstarved T. ferrooxidans cells but also that it is specific for this microorganism, since the other biomining bacteria gave only a marginal reaction with the antibodies.

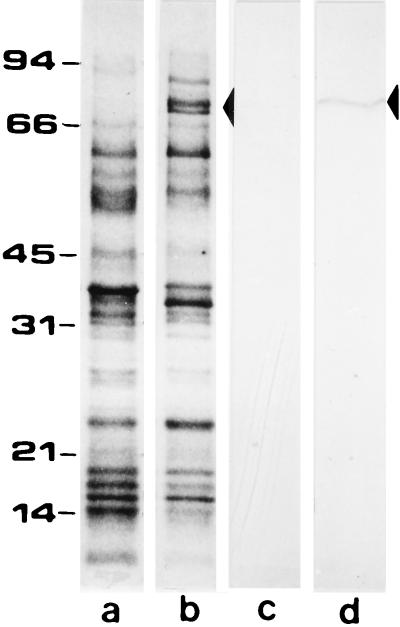

To detect the specific expression of P2 in T. ferrooxidans we employed a standard Western blotting (immunoblotting) procedure. The total proteins from control and phosphate-starved cells were separated by SDS-PAGE as shown in Fig. 3. The phosphate-starved cells showed a great induction of two bands in the 70- to 80-kDa molecular mass range (arrowhead, lane b), bands which were entirely absent in the control cells (lane a). When these proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to Western immunoblotting with P2 antiserum, we observed a clear reaction only in the phosphate-starved cells (arrowhead, lane d). The P2 doublet was not always well separated; it sometimes migrated as a single band as seen here in the immunoblot (lane d).

FIG. 3.

Western blotting of T. ferrooxidans total proteins. Proteins from T. ferrooxidans cells grown in the presence (lanes a and c) or in the absence of phosphate (lanes b and d) were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue (lanes a and b) or subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against surface proteins P2 (lanes c and d). The arrowheads indicate the migrating position of the P2 bands.

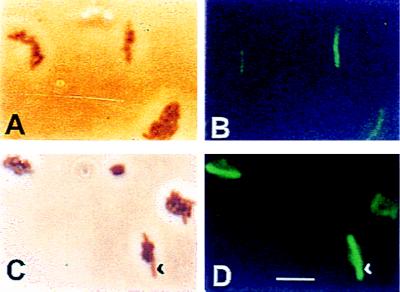

We have previously reported that phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans cells show a filamentous morphology, which is probably due to a lack of cell division under these conditions (20). Figure 4 shows that when a mixture of both control and phosphate-starved cells was analyzed by phase-contrast microscopy (panels A and C) it was possible to distinguish from among a group of normal cells some very elongated ones that corresponded to the starved microorganisms (20). Note, for example, the group of normal size cells in the bottom right side of panel C, in which a single cell ca. 6 μm long is present (arrowhead). When the same groups of cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy, the antibody raised against the P2 proteins reacted only with the intact phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans target cells. This is clearly seen by the strong fluorescence of the elongated cells (see arrowhead indicating one example). This confirms the much greater specificity of the antiserum for the detection of the phosphate-starved cells. In addition, our results showed that the P2 proteins possessed surface-exposed epitopes and that their interaction with the antibodies was not masked by LPS as shown above.

FIG. 4.

Monitoring of the phosphate starvation condition in T. ferrooxidans cells by immunofluorescence microscopy. A mixture in equal proportions of control and phosphate-starved T. ferrooxidans cells was observed by phase-contrast microscopy (A and C) or immunofluorescence microscopy (B and D) with antiserum to P2. Bar, 5 μm.

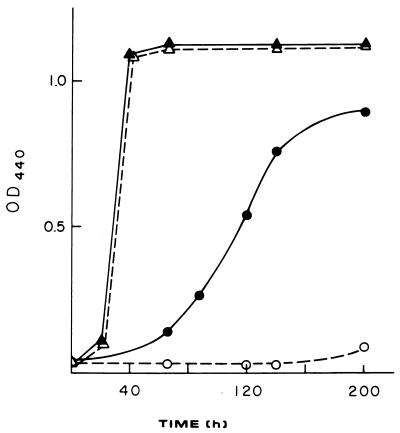

The relevance of the immunological method developed to determine the levels of phosphate in T. ferrooxidans can be illustrated in practical terms by analyzing the response of phosphate-starved cells to toxic arsenic compounds. Arsenate is a well-known analog of phosphate. This anion enters Escherichia coli cells via the same transport system used for phosphate (14). Consequently, when the phosphate-scavenging system is induced, the entrance of the toxic oxyanion would be facilitated. According to this scenario, cells starved for phosphate would be expected to be much more affected by the presence of arsenate. To test whether this situation actually occurred in T. ferrooxidans, we cultivated the microorganism in the presence or absence of phosphate and also in the presence of low concentrations of arsenate (2 mM) (Fig. 5). As predicted, normal cells grown in the presence of phosphate were not affected by arsenate. However, phosphate-starved cells were greatly inhibited in their ability to grow by the presence of 2 mM arsenate. These results are very important in bioleaching operations in which ores containing arsenic, such as arsenopyrites, are present, since as they become solubilized, the levels of arsenic III and arsenic V greatly increase. Although strains of T. ferrooxidans with high arsenic resistance levels have been isolated (17), it is clear from the results shown here that the levels of bioavailable phosphate present may greatly affect the resistance of the microorganisms to arsenate and, consequently, the overall efficiency of biomining.

FIG. 5.

Effect of low levels of arsenate on the growth of phosphate-starved cells of T. ferrooxidans. Cells were grown in the presence (▴ and ▵) or absence (• and ○) of phosphate and in the presence of 2 mM arsenate (▵ and ○).

Recently, similar immunological methods based on the detection of the induction of proteins due to phosphate limitation have been described for Pseudomonas fluorescens (12) and Synechococcus sp. (18). In both cases, however, the phosphate-induced proteins used as markers of this condition were not exposed in the surface of the cells, and it was therefore necessary to permeabilize the bacteria in order to perform the immunofluorescence assay (12, 18). The P2 proteins from T. ferrooxidans have the advantage of being exposed in the surface of the cells. This makes it unnecessary to pretreat the samples to permeabilize the cells, a procedure that is not always complete and may vary from one sample to another (especially when one is using field samples). Some of the substances normally present in biomining ore-leaching samples may interfere with immunological assays. However, most of these substances are eliminated by adjusting the pH of the sample to 1.5. This dissolves most of the precipitated metal hydroxides, which are eliminated after the samples containing the cells are applied to the nitrocellulose membranes by filtering and then washed several times.

The antibodies prepared against the outer membrane proteins of T. ferrooxidans obviously constitute a useful tool for the monitoring of the phosphate starvation condition of cells. This immunological assay analysis could be eventually applied to ore-attached cells, or alternatively, cells could first be detached from the solid (6, 8) and then their phosphate starvation condition could be assessed by immunofluorescence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by FONDECYT grant 197/0417, ICGEB grant 96/007, and SAREC.

We thank A. M. Amaro for measurements of T. ferrooxidans growth in the presence of arsenate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amaro A M, Chamorro D, Seeger M, Arredondo R, Peirano I, Jerez C A. Effect of external pH perturbations on in vivo protein synthesis by the acidophilic bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:910–915. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.910-915.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amaro A M, Hallberg K B, Lindström E B, Jerez C A. An immunological assay for the detection and enumeration of thermophilic biomining microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3470–3473. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3470-3473.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arredondo R, García A, Jerez C A. Partial removal of lipopolysaccharide from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans affects its adhesion to solids. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2846–2851. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2846-2851.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arredondo R, Jerez C A. A specific dot-immunobinding assay for detection and enumeration of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:2025–2029. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.2025-2029.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauw G, Van Damme J, Puype M, Vandekerckhove J, Gesser B, Ratz G P, Lauridsen J B, Celis J E. Protein-electroblotting and -microsequencing strategies in generating protein databases from two-dimensional gels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:7701–7705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.20.7701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.García A, Jerez C A. Changes of the solid-adhered populations of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans, Leptospirillum ferrooxidans and Thiobacillus thiooxidans in leaching ores as determined by immunological analysis. In: Jerez C A, Vargas T, Toledo H, Wiertz J, editors. Biohydrometallurgical processing. Santiago, Chile: University of Chile; 1995. pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jerez C A. The heat shock response in meso- and thermophilic chemolithotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;56:289–294. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerez C A. Molecular methods for the identification and enumeration of bioleaching microorganisms. In: Rawlings D, editor. Biomining: theory, microbes and industrial processes. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1997. pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jerez C A, Arredondo R. A sensitive immunological method to enumerate Leptospirillum ferrooxidans in the presence of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;78:99–102. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jerez C A, Seeger M, Amaro A M. Phosphate starvation affects the synthesis of outer membrane proteins in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;98:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90127-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leopold K, Jacobsen S, Nybroe O. A phosphate-starvation-inducible outer-membrane protein of Pseudomonas fluorescens Ag1 as an immunological phosphate-starvation marker. Microbiology. 1997;143:1019–1027. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-3-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lundgren D G, Silver M. Ore leaching by bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:263–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.001403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nies D H, Silver S. Ion efflux systems involved in bacterial metal resistances. J Ind Microbiol. 1995;14:186–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01569902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Farrell P Z, Goodman H M, O’Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of basic as well as acidic proteins. Cell. 1977;12:1133–1142. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90176-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osorio G, Jerez C A. Adaptive response of the archaeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius BC65 to phosphate starvation. Microbiology. 1996;142:1531–1536. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-6-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rawlings D E, Kusano T. Molecular genetics of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:39–55. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.1.39-55.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scanlan D J, Silman N J, Donald K M, Wilson W H, Carr N G, Joint I, Mann N H. An immunological approach to detect phosphate stress in populations and single cells of photosynthetic picoplankton. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2411–2420. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.6.2411-2420.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seeger M, Jerez C A. Phosphate limitation affects global gene expression in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Geomicrobiol J. 1992;10:227–237. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seeger M, Jerez C A. Response of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans to phosphate limitation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;11:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seeger M, Osorio G, Jerez C A. Phosphorylation of GroEL, DnaK and other proteins from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans grown under different conditions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;138:129–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tuovinen O. Biological fundamentals of mineral leaching processes. In: Ehrlich H L, Brierley C L, editors. Microbial mineral recovery. New York, N.Y: McGraw-Hill Book Co.; 1990. pp. 55–77. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Ley P, Kuipers O, Tommassen J, Lugtenberg B. O-antigenic chains of lipopolysaccharide prevent binding of antibody molecules to an outer membrane pore protein in Enterobacteriaceae. Microb Pathog. 1986;1:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(86)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varela P, Jerez C A. Identification and characterization of GroEL and DnaK homologues in Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;98:149–154. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90147-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zaat S A J, Slegtenhorst-Eegdeman K, Tommassen J, Geli V, Wijffelman C A, Lugtenberg B J J. Construction of phoE-caa, a novel PCR- and immunologically detectable marker gene for Pseudomonas putida. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3965–3973. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.3965-3973.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]