Abstract

Background

Several studies have suggested that increased oxidative stress during pregnancy may be associated with adverse maternal and foetal outcomes. As selenium is an essential mineral with an antioxidant role, our aim was to perform a systematic review of the existing literature reporting the effects of selenium supplementation during pregnancy on maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Materials and Methods

Six electronic databases (Medline, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Scopus, and PubMed) were searched for studies reporting the effects of selenium supplementation during pregnancy and the postpartum period on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Only randomised controlled trials on human subjects reported in English and published up to October 2021 were included. Quality assessments were conducted using the modified Downs and Black quality assessment tool. Data were extracted using a narrative synthesis.

Results

Twenty-two articles were included in our systematic review (seventeen reported on maternal outcomes, two on newborn outcomes, and three on both). Maternal studies reported the effects of selenium supplementation in the prevention of thyroid dysfunction, gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension/preeclampsia, oxidative stress, postpartum depression, premature rupture of membranes, intrauterine growth retardation, breastmilk composition, and HIV-positive women. Newborn studies reported the effects of maternal selenium supplementation on foetal oxidation stress, foetal lipid profile, neonatal hyperbilirubinemia, and newborn outcomes in HIV-positive mothers. The majority of studies were inappropriately designed to establish clinical or scientific utility. Of interest, four studies reported that selenium supplementation reduced the incidence of thyroid dysfunction and permanent hypothyroidism during the postpartum period by reducing thyroid peroxidase and thyroglobulin antibody titres.

Conclusion

The evidence supporting selenium supplementation during pregnancy is poor and there is a need for appropriately designed randomised controlled trials before routine use can be recommended.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy places significant demands on maternal nutrients due to both the developing foetus and maternal physiological and hormonal changes. It is recognised that deficiencies of essential vitamins and minerals during this period may lead to the occurrence of perinatal complications, foetus necrobiosis, congenital malformation, and impairment of immune system function in the developing foetus [1–3].

Although current guidelines only advocate iron and folic acid supplementation during pregnancy, there is an increasing interest in the role which other micronutrients may play [1, 4–7]. Selenium (Se), a micronutrient with antioxidant properties, is essential for the synthesis and function of various selenoenzymes such as glutathione peroxidases, selenoproteins P, and thioredoxin reductase, which play important roles in antioxidant defence and limiting oxidative damage [8–12]. Available evidence suggests that Se plasma concentration and glutathione peroxidase activity decrease during pregnancy, due in part to the increasing erythrocyte mass in the developing foetus [13–16].

During pregnancy both maternal and foetal oxygen demand increase, which enhances formation of reactive oxygen species and lipid peroxidation products [15, 17]. It has been previously reported that increased oxidative stress during pregnancy is associated with the occurrence of maternal and foetal/neonatal diseases and adverse outcomes such as miscarriage, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, premature rupture of membranes, and intrauterine growth restriction. Therefore, Se could be an important micronutrient during the gestational period [18–28]. Se is found in soils and rocks at varying levels across the world. Soil Se level affects plant Se levels, which influences the levels of Se entering the food chain. Consequently, the geographical variation in soil Se levels has a significant effect on dietary Se intake and status in different populations throughout the world [29].

Se supplementation during pregnancy might reduce maternal oxidative stress and have a favourable outcome on both the mother and the foetus [30]. During pregnancy recommended dietary allowance for Se is 60 μmg (0.76 μmol) Se/day [31]. However currently, there are no published systematic reviews assessing the beneficial or adverse effects of Se supplementation during pregnancy. This systematic review aims to retrieve the primary literature reporting the effects of Se supplementation during pregnancy and the postnatal period, to determine whether Se supplementation is associated with any beneficial or adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Sources

The Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), Excerpta Medica Database (Embase), Web of Science, the Cochrane Library, Scopus, and PubMed were searched from inception until October 2021. Only publications in English were included.

We applied a three-step search strategy. An initial limited search of MEDLINE was undertaken followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract of the article and of index terms used to describe the article. A second search was done using all identified keywords and index terms across all six databases. Thirdly, we searched the reference list of all identified articles and reports for any additional studies. The following search string was used:

(Selenium∗ OR “Se Supplement∗” OR “Selenium supplement∗”) AND (Pregnancy∗ OR Pregnan∗ OR “Maternal health∗” OR “Maternal mortality∗” OR “Maternal outcomes∗” OR Newborn∗ OR Neonat∗ OR “Neonatal health∗” OR “Neonatal mortality∗” OR “Neonatal outcome”) AND (“Outcome” OR “Effect” OR “Treatment effect∗” OR “Supplementation effect∗”)

2.2. Study Selection

Randomised placebo-controlled trials including cluster-randomised trials were considered for inclusion. We excluded articles on quasi-randomised trials, cross-over designs, and all other types of research designs.

For maternal outcomes, all studies that reported any maternal health benefits or harmful effects associated with Se supplementation during pregnancy and postnatal period were included. We considered studies regardless of the stage of pregnancy at which supplementation was started and irrespective of supplementation taken previously.

Similarly, for newborn outcomes, all studies that reported any health benefits or harms in newborns (neonates and infants) following Se supplementation during pregnancy were included irrespective of the health status of the mother.

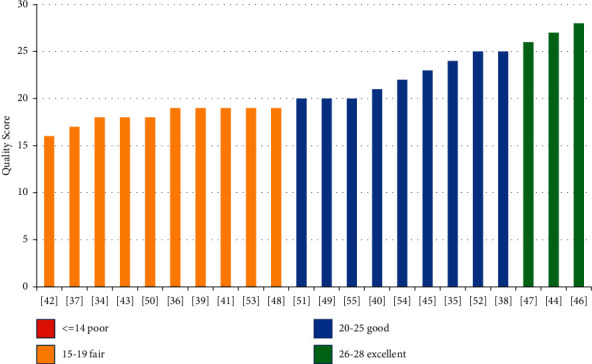

Quality assessments were conducted by two reviewers (K.B. and J.M.) using modified Downs and Black quality assessment tool for randomised controlled trials included in this study [32, 33]. Downs and Black quality assessment tool score gave corresponding quality levels: excellent (26–28), good (20–25), fair (15–19), and poor (≤14) out of a maximum of 28 points. The relevant items on the quality assessment tool checklist were focused aim of the study, randomisation methodology, participant dropout recording, blinding (single/double), baseline characteristics matching between the two groups, whether factors other than treatment were the same for both groups, treatment effect size, the precision of the study, the applicability of the study findings to the general population, and if all clinically important outcomes were considered [32].

A tailored spreadsheet was constructed for data extraction and data synthesis. All studies identified during the database search were assessed for relevance to our review protocol and quality assessed based on information obtained from the title, abstract, and full-text review by two reviewers (K.B and J.M.). If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer (F.C.) was consulted.

The key data extracted from selected literature were details of the authors; country and year of publication; Se supplementation product and placebo product used; study population; setting; recruitment; randomisation methodology; blinding technique; baseline characteristics of groups; initiation and duration of supplementation; incidence and magnitude of beneficial/adverse effects; statistical methods used for analysis and risk of bias. Data extracted from trials were the generation of allocation sequence, concealment of allocation, outcome measures, and other risks of bias.

Owing to lack of study homogeneity, a meta-analysis was not appropriate; thus, a narrative synthesis of the results was conducted. Wherever available, statistical data were reported. A systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CDR42020183126). The PRISMA checklist was used to guide the reporting of this systematic review.

3. Results

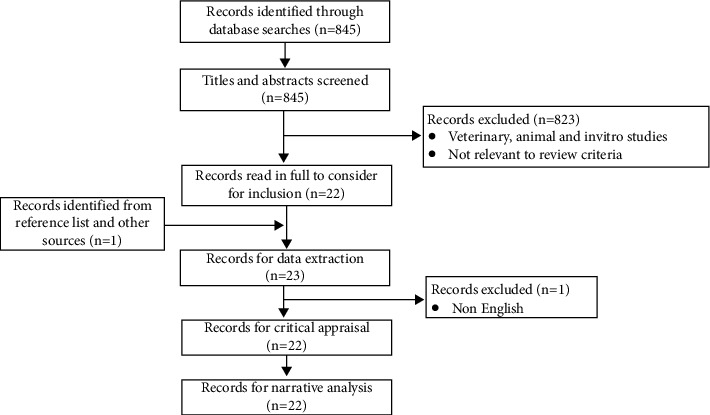

Database searches retrieved a total of 845 citations. After removal of duplicates, title and abstract screening, and full-text screening, 22 articles, meeting inclusion criteria, were critically appraised. These 22 articles were included for data extraction, synthesis, and narrative analysis (Figure 1). Included studies were performed in seven different countries and 18 were primary [34–39, 41–48, 51, 53–55] while four were secondary studies [40, 49, 50, 52]. Ten studies were graded as fair [34, 36, 37, 39, 41–43, 48, 50, 53], nine as good [35, 38, 40, 45, 49, 51, 52, 54, 55], and three as excellent quality [44, 46, 47] (Figure 2). Seventeen studies reported maternal outcomes, two reported neonatal outcomes, and three reported both.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis) flowchart.

Figure 2.

Quality scores of papers included for review (based on Downs and Black assessment tool).

Nine different maternal outcomes were reported. The sample size for studies ranged from 36 to 913. The methods used to identify maternal outcomes were clinical examination, patient questionnaires, laboratory or imaging studies (i.e., haematological, biochemical, gene expression, and ultrasonography), and secondary data analysis. Out of the twenty studies reporting maternal outcomes, three studies did not report significant findings. Table 1 presents the narrative synthesis of the different maternal outcomes.

Table 1.

Reported maternal outcomes on Se supplementation.

| Clinical condition | Result of Se supplementation | Reference/Country/Sample size (n)/Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) | Se supplementation during pregnancy effectively reduced the incidence of PROM when compared to placebo (13.1% vs. 34.4%, p < 0.01) | [34]/Iran/n = 125/fair |

| Intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR) | After 10 weeks of Se supplementation, a higher percentage of women in the Se group had pulsatility index (PI) of <1.45) (p=0.002) than of those in the placebo group. However, no comparison was made of the birth weight of babies in both groups. | [35]/Iran/n = 60/good |

| Postpartum depression | The mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score in the selenium supplemented group was significantly lower than the control group (8.8 + 5.1 vs. 10.7 + 4.4, p < 0.05) | [36]/Iran/n = 85/fair |

| Oxidative stress | Se supplementation reduced oxidative stress associated with pregnancy, as demonstrated by the PAB assay (167.3 (135.4–221) vs. 221.0 (162.0–223.3), p < 0.05) | [37]/Iran/n = 125/fair |

| Gestational diabetes | Se supplementation, compared with placebo, resulted in a significant reduction in fasting plasma glucose, serum insulin levels, and homeostasis model of assessment- (HOMA-) insulin resistance and a significant increase in quantitative insulin sensitivity check index | [38]/Iran/n = 70/good |

| Se supplementation downregulated gene expression of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and upregulated gene expression of VEGF in lymphocytes of patients with GDM | [39]/Iran/n = 40/fair | |

| Se supplementation did not cause any significant difference in the adiponectin level (which is inversely related to insulin resistance) from 12 to 35 weeks of gestation (p=0.938) | [40]/UK/n = 230/good | |

| Se supplementation resulted in upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (p=0.03) and glucose transporter 1 (p=0.01) in lymphocytes of patients with GDM. | [41]/Iran/n = 36/fair | |

| Breastmilk | Se supplementation increased breastmilk selenium level but did not significantly increase breastmilk glutathione peroxidase activity | [42]/China/n = 20/fair |

| Se supplementation increased breastmilk Se concentration (p=0.003), did not change breastmilk glutathione peroxidase activity, significantly increased the concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids (p=0.02), mainly linoleic acid (p=0.02), and decreased the concentration of saturated fatty acids in breast milk (p=0.04) | [43]/New Zealand/n = 22/fair | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive women | No significant effect on maternal CD4 cell count, viral load, and maternal mortality (RR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.51, 2.04; p=0.96) | [44]/Tanzania/n = 913/excellent |

| The proportion of women with detectable HIV-1 RNA in breast milk increased in Se supplemented (36.4%) than placebo (27.5%) group. The effect was more in primiparas. | [45]/Tanzania/n = 420/good | |

| Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive women | Se supplementation significantly lowered risk of preterm delivery (relative risk (RR) 0.32, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.11–0.96) compared to placebo. Se supplementation caused no effect on HIV-disease progression in pregnant women. | [46]/Nigeria/n = 180/excellent |

| Thyroid disorder | Se supplementation lowered TPO Ab titres during the postpartum period compared to controls (323.2 ± 44 vs. 621.1 ± 80 kIU/litre) (p < 0.01). Postpartum thyroid dysfunction and permanent hypothyroidism were significantly lower in selenium supplemented population compared with controls (28.6 vs. 48.6%, p < 0.01; and 11.7 vs. 20.3%, p < 0.01). | [47]/Italy/n = 232/excellent |

| From 36 weeks' gestation to 6 months' postpartum, Se supplementation decreased Tg Ab [19.86 (11.59–52.60) IU/ml; p < 0.01] in a thyroiditis positive population but it increased in the control group (151.03 ± 182.9 IU/ml; p < 0.01). TPO Ab also decreased on Se supplementation (255.00 (79.00–292.00) IU/ml; p < 0.01) but increased in the control group (441.28 ± 512.18 IU/ml; p < 0.01) during the same period. | [48]/Italy/n = 45/fair | |

| Thyroid disorder | Low-dose Se supplementation in pregnant women with mild-to-moderate deficiency had no effect on TPO Ab concentration from 12 to 35 weeks of gestation but tended to change thyroid function in TPO Ab + ve women in late gestation (35 weeks): reduced TSH (2.10 (1.83, 2.38) vs. 2.50 (2.24, 2.79) mU/l, p=0.05p=0.05), reduced FT4 (10.54 (9.83,11.25) vs. 11.67 (11.03 vs. 12.31) pmol/l, p=0.029p=0.029) | [49]/UK/n = 229/good |

| Se supplementation did not affect TPO Ab or TSH level in pregnant women. During late gestation (35 weeks), serum FT4 levels were lower in the selenium-treated women compared to controls (10.54 vs. 10.82 pmol/l, p=0.029). | [50]/UK/n = 230/fair | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH)/preeclampsia (PE) | There was no incidence of preeclampsia in the treated group, but 4.7% (n = 3) of women in the control group suffered from preeclampsia (statistically nonsignificant) | [51]/Iran/n = 125/good |

| Se supplementation significantly lowered the concentration of soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sFlt-1), which is a biomarker of preeclampsia, among the Se deficient women. However, the difference in the concentration of other biomarkers was not significant. | [52]/UK/n = 230/good | |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH)/preeclampsia (PE) | Se supplementation in a Se deficient UK population significantly reduced the odds ratio for PE/PIH (OR 0·30, 95% CI 0·09, 1·00, p=0.049) | [53]/UK/n = 230/fair |

Four studies (two classified as fair and two as good; n = 45–232) reported on thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Se supplementation did not affect maternal thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO Ab) or thyroglobulin antibody (Tg Ab) from 12 to 35 weeks of gestation [49, 50] but resulted in a decrease of these antibody titres from 36 weeks' gestation to 6 months' postpartum in a thyroiditis positive population [48]. Postpartum thyroid dysfunction and permanent hypothyroidism were significantly reduced in Se supplemented population compared with controls (28.6 vs. 48.6%, p < 0.01; and 11.7 vs. 20.3%, p < 0.01) [47].

Three trials reported the effect of Se supplementation on the incidence of pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH)/preeclampsia (PE). One good quality study conducted on Se deficient women reported that Se supplementation significantly reduced the Odds Ratio for PE/PIH (OR 0·30, 95% CI 0·09, 1·00, p=0.049) [53]. A second study of good quality reported that Se supplementation significantly decreased soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (sFLT-1), a biomarker of preeclampsia but did not affect other biomarkers [52]. A third study of fair quality reported that Se supplementation did not significantly decrease the incidence of preeclampsia [51].

Four trials reported the effect of Se supplementation on gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). One good quality study reported that Se supplementation resulted in a significant reduction in serum insulin levels, fasting plasma glucose, and homeostasis model of assessment- (HOMA-) insulin resistance and a significant increase in quantitative insulin sensitivity check index [38]. A second study, of fair quality, reported that Se supplementation downregulated gene expression of tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and upregulated gene expression of VEGF in lymphocytes of patients with GDM [39]. A third study, of good quality, did not find any significant difference in the adiponectin level (which is inversely related to insulin resistance) with Se supplementation [40]. A fourth trial, of fair quality, reported that Se supplementation resulted in upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ and glucose transporter 1 in lymphocytes of patients with GDM but did not correlate this with any clinical utility observed in the patients [41].

Two small trials, of fair quality, reported that Se supplementation increased breast milk Se concentration but did not change breast milk glutathione peroxidase activity [42,43], increased polyunsaturated fatty acids (p=0.02), especially linoleic acid (p=0.02), and decreased saturated fatty acids concentration of breast milk (p=0.04) [43].

Three trials were conducted on HIV-positive pregnant women. One excellent quality study reported that Se supplementation had no significant effect on maternal CD4 cell count, viral load, and maternal mortality (RR = 1.02; 95% CI = 0.51, 2.04; p=0.96) [44]. The second study, of good quality, reported that Se supplementation increased detectable HIV-1 RNA in breast milk (36.4% vs. 27.5%) [45]. The third trial, of excellent quality, reported that Se supplementation significantly lowered the risk of preterm delivery (relative risk 0.32, 95% confidence interval 0.11–0.96) compared to placebo. But it did not affect HIV-disease progression in pregnant women, as evidenced by no significant changes in CD4+ cell count [46].

A fair quality trial reported that Se supplementation during pregnancy effectively reduced the incidence of premature rupture of membranes when compared to placebo (13.1% vs. 34.4%, p < 0.01) [34]. Another small study of fair quality reported that the mean Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) score in Se supplemented group was significantly lower than the control group (8.8 + 5.1 vs. 10.7 + 4.4, p < 0.05); thus it could help in reducing postpartum depression [36].

A small fair quality trial reported that, after 10 weeks of Se supplementation, a higher percentage of women in the Se group had a pulsatility index (PI) of <1.45 (p=0.002) compared to those in the placebo group, suggesting it could help in reducing intrauterine growth retardation. However, newborn birth weight was not compared in either the treated or the control groups [35]. Another fair quality study reported that Se supplementation reduced oxidative stress associated with pregnancy, as demonstrated by PAB assay [167.3 (135.4–221) vs. 221.0 (162.0–223.3), p < 0.05]. However, this study lacked any clinical utility [37].

Five trials reported the effect of Se supplementation on neonatal outcomes (Table 2). An excellent quality trial reported that Se supplementation in HIV-positive mothers reduced risk of low birth weight babies [relative risk (RR) = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.49, 1.05; p=0.09p=0.09) and child mortality after 6 weeks (RR = 0.43; 95% CI = 0.19, 0.99; p=0.048) but increased the risk of foetal death (RR = 1.58; 95% CI = 0.95, 2.63; p=0.08) [44]. Another excellent trial reported that Se supplementation resulted in a nonsignificant reduction in the risk of delivering low birth weight babies at term pregnancy (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.05–1.19) [46]. A fair quality trial reported that maternal Se supplementation increased cord blood Se (106.3 ± 18.2 vs. 101.9 ± 15.9, p=0.29) and increased foetal PAB [37.2(26.1–121.0) vs. 30.8(24.0–45.5), p=0.19] [54]. Another fair quality trial reported that maternal Se supplementation increased cord blood triglyceride level (56 vs. 38.5 mg/dl) (p < 0.001) [53]. There was no effect of Se supplementation on the foetal sex, gestational age at birth, birth weight, birth length, head circumference, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes, and newborn mortality and morbidity [54, 55]. The fifth study, of fair quality, reported that selenium supplementation in GDM patients significantly decreased the incidence of hyperbilirubinemia (5.6% vs. 33.3%, p=0.03) and hospitalization (5.6% vs. 33.3%, p=0.03) in newborn infants [41].

Table 2.

Reported neonatal outcomes on Se supplementation.

| Clinical condition | Result of Se supplementation | Reference/Country/Sample size (n)/Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Neonatal oxidative stress | Se supplementation increased foetal cord blood selenium levels (106.3 ± 18.2 vs. 101.9 ± 15.9, p=0.29) and increased foetal PAB (37.2(26.1–121.0) vs. 30.8(24.0–45.5), p=0.19). But there was no effect on foetal birth weight, gestational age at birth, Apgar score at 1 and 5 minutes, newborn mortality, and morbidity. | [54]/Iran/n = 125/good |

| Cord blood Se and lipid profile | Se supplementation during pregnancy did not significantly change the cord blood selenium (106.3 vs. 101.9 μg/L), total cholesterol (96.7 vs. 79.6 mg/dl), LDL-C (58 vs. 45.1 mg/dl), and HDL-C (23 vs. 20.2 mg/dl) levels but increased the serum triglyceride level (56 vs. 38.5 mg/dl) (p < 0.001). There was no effect of Se supplementation on the foetal sex, gestational age at birth, birth weight, birth length, head circumference, and Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes. | [55]/Iran/n = 66/good |

| HIV | Maternal Se supplementation reduced risk of low birth weight babies (relative risk (RR) = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.49, 1.05; p=0.09) and risk of child mortality after 6 weeks (RR = 0.43; 95% CI = 0.19, 0.99; p=0.048), but it increased risk of foetal death (RR = 1.58; 95% CI = 0.95,2.63; p=0.08). There was no effect on risk of prematurity or small-for-gestational age birth. | [44]/Tanzania/n = 913/excellent |

| Se supplementation resulted in a nonsignificant reduction in the risk of delivering low birth weight babies at term pregnancy (RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.05–1.19). | [46]/Nigeria/n = 180/excellent | |

| Newborn Hyperbilirubinemia |

Selenium supplementation in GDM patients significantly decreased incidence of newborns' hyperbilirubinemia (5.6% vs. 33.3%, p=0.03) and newborns' hospitalization (5.6% vs. 33.3%, p=0.03). | [41]/Iran/n = 36/fair |

4. Discussion

The majority of studies included in our review reported Se supplementation in pregnancy to be of benefit, reducing PE/PIH, GDM, IUGR, PROM, postpartum depression, and postpartum thyroid dysfunction. Se supplementation is also reported to affect breast milk composition, foetal lipid profile, and foetal bilirubin level and has mixed outcomes in HIV-positive mothers and their newborns.

It is reported that oxidative stress increases during pregnancy [37] and this increased stress is associated with many pregnancy-related illnesses. The blood level of Se decreases during pregnancy mainly due to haemodilution and transport to the developing foetus. Thus, Se, which has antioxidant properties, may be a highly useful supplement during gestation to overcome this increased oxidative stress.

We identified a small number of randomised controlled trials focusing on maternal and newborn outcomes following Se supplementation. Although the majority of available studies were graded as fair and good, results were contradictory and there were significant methodological issues in the published reports which limited interpretability and generalisability.

The main finding in this review is the evidence that Se supplementation helps to reduce postpartum thyroid dysfunction. A well-designed study by Negro et al. [47], graded as excellent, reported that Se supplementation decreased TPO Ab in the postpartum period and reduced the incidence of postpartum thyroid dysfunction and permanent hypothyroidism. Mantovani et al. [48] in a small study (n = 45) reported that Se supplementation decreased Tg Ab from 36 weeks' pregnancy to 6 months' postpartum period in thyroiditis positive women. Both these studies suggest that Se supplementation may help reduce postpartum thyroid dysfunction; however further research is needed to validate these findings and determine the therapeutic Se dose for such patients.

Another important finding of our review is the evidence for Se supplementation in HIV-positive pregnant women. A well-designed trial by Kupka et al. [44] reported that supplementation in HIV-positive mothers reduced the risk of low birth weight babies and child mortality after 6 weeks of birth but increased the risk of foetal death. Another well-designed trial by Okunade et al. [46] reported that selenium supplementation in HIV-positive mothers significantly reduced the risk of preterm delivery. A third study on HIV-positive mothers by Sudfeld et al. [45] reported that Se supplement increased detectable HIV-1 RNA in breast milk among women who did not take antiretroviral drugs and thus Se could increase the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Hence, Se supplementation may better be avoided in HIV-positive mothers until a robust advantage is evident.

The main advantage of our study is that we included only single or double-blind randomised controlled trials for review; we did not rely on observational data from other types of study. Our study was not without limitations. Out of the 22 studies, four were secondary studies [40, 49, 50, 52] which were originally designed to study other aspects of Se supplementation. Only two primary studies measured Se status of participants at the baseline [48, 51]. Only five studies had a power calculation to determine the sample size [38, 41, 44, 46, 47]. Only three studies included in our review were of excellent quality. The dose and composition of Se supplement were not uniform in all the studies. Adverse events from Se supplement use were underreported in these studies. Six studies conducted in Iran [34, 36, 37, 51, 54, 55] and five studies conducted in the UK [40, 49–52] were on the same population cohort, respectively.

5. Conclusion

Available evidence confirms the effect of Se supplementation on maternal or newborn outcomes is understudied and currently unknown. The evidence-based use of nutritional supplementation in pregnancy must be backed by robust appropriately designed and powered clinical trials. Currently, there is insufficient information to recommend the safe use of Se supplementation during pregnancy and the postnatal period. The safe dosage of Se supplement in pregnancy needs to be determined.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Black R. E. Micronutrients in pregnancy. British Journal of Nutrition . 2001;85(S2):S193–S197. doi: 10.1079/BJN2000314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfrey K., Robinson S., Barker D. J., Osmond C., Cox V. Maternal nutrition in early and late pregnancy in relation to placental and fetal growth. BMJ . 1996;312(7028):p. 410. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7028.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maggini S., Wintergerst E. S., Beveridge S., Hornig D. H. Selected vitamins and trace elements support immune function by strengthening epithelial barriers and cellular and humoral immune responses. British Journal of Nutrition . 2007;98(S1):S29–S35. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507832971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen L. H. Multiple micronutrients in pregnancy and lactation: an overview. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 2005;81(5):p. 1206S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christian P., West K. P., Jr., Khatry S. K., et al. Vitamin A or β-carotene supplementation reduces symptoms of illness in pregnant and lactating Nepali women. The Journal of Nutrition . 2000;130(11):2675–2682. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenville M. Nutritional supplements in pregnancy: commercial push or evidence based? Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology . 2006;18(6):642–647. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328010214e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong J., Park E. A., Kim Y. J., et al. Association of antioxidant vitamins and oxidative stress levels in pregnancy with infant growth during the first year of life. Public Health Nutrition . 2008;11(10):998–1005. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007001322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas A. C., Zoidis E., Surai P. F., Zervas G. Selenoproteins and maternal nutrition. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part B: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology . 2008;151(4):361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lei X. G., Cheng W. H., McClung J. P. Metabolic regulation and function of glutathione peroxidase-1. Annual Review of Nutrition . 2007;27:41–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.27.061406.093716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navarro-Alarcon M., Cabrera-Vique C. Selenium in food and the human body: a review. Science of the Total Environment . 2008;400(1–3):115–141. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ravn-Haren G., Bügel S., Krath B. N., et al. A short-term intervention trial with selenate, selenium-enriched yeast and selenium-enriched milk: effects on oxidative defence regulation. British Journal of Nutrition . 2008;99(4):883–892. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507825153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tapiero H., Townsend D. M., Tew K. D. The antioxidant role of selenium and seleno-compounds. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2003;57(3-4):134–144. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(03)00035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasowicz W., Wolkanin P., Bednarski M., Gromadzinska J., Sklodowska M., Grzybowska K. Plasma trace element (Se, Zn, Cu) concentrations in maternal and umbilical cord blood in Poland. Biological Trace Element Research . 1993;38(2):205–215. doi: 10.1007/BF02784053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zachara B. A., Wąsowicz W., Gromadzińska J., Skłodowska M., Krasomski G. Glutathione peroxidase activity, selenium, and lipid peroxide concentrations in blood from a healthy polish population. Biological Trace Element Research . 1986;10(3):175–187. doi: 10.1007/BF02795616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihailović M., Cvetković M., Ljubić A., et al. Selenium and malondialdehyde content and glutathione peroxidase activity in maternal and umbilical cord blood and amniotic fluid. Biological Trace Element Research . 2000;73(1):47–54. doi: 10.1385/BTER:73:1:47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rayman M. P. Selenium and human health. The Lancet . 2012;379(9822):1256–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Uotila J., Tuimala R., Aarnio T., Pyykkö K., Ahotupa M. Lipid peroxidation products, selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase and vitamin E in normal pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology . 1991;42(2):95–100. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90168-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Biri A., Onan A., Devrim E., Babacan F., Kavutcu M. U., Durak I. Oxidant status in maternal and cord plasma and placental tissue in gestational diabetes. Placenta . 2006;27(2-3):327–332. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chamy V. M., Lepe J., Catalán A., Retamal D., Escobar J. A., Madrid E. M. Oxidative stress is closely related to clinical severity of pre-eclampsia. Biological Research . 2006;39(2):229–236. doi: 10.4067/S0716-97602006000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X., Scholl T. O., Leskiw M. J., Donaldson M. R., Stein T. P. Association of glutathione peroxidase activity with insulin resistance and dietary fat intake during normal pregnancy. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism . 2003;88(12):5963–5968. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dobrzynsky W., Trafikowska U., Trafikowska A., Pilecki A., Szymanski W., Zachara B. A. Decreased selenium concentration in maternal and cord blood in preterm compared with term delivery. Analyst . 1998;123:93–97. doi: 10.1039/A704884J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grissa O., Atègbo J. M., Yessoufou A., et al. Antioxidant status and circulating lipids are altered in human gestational diabetes and macrosomia. Translational Research . 2007;150(3):164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holmes V. A., McCance D. R. Could antioxidant supplementation prevent pre-eclampsia? Proceedings of the Nutrition Society . 2005;64(4):491–501. doi: 10.1079/PNS2005469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longini M., Perrone S., Vezzosi P., et al. Association between oxidative stress in pregnancy and preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clinical Biochemistry . 2007;40(11):793–797. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehendale S., Kilari A., Dangat K., Taralekar V., Mahadik S., Joshi S. Fatty acids, antioxidants, and oxidative stress in pre-eclampsia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics . 2008;100(3):234–238. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jauniaux E., Poston L., Burton G. J. Placental-related diseases of pregnancy: involvement of oxidative stress and implications in human evolution. Human Reproduction Update . 2006;12(6):747–755. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surapaneni K. M. Oxidant–antioxidant status in gestational diabetes patients. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research . 2007;1:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tastekin A., Ors R., Demircan B., Saricam Z., Ingec M., Akcay F. Oxidative stress in infants born to preeclamptic mothers. Pediatrics International . 2005;47(6):658–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Combs G. F. Selenium in global food systems. British Journal of Nutrition . 2001;85(5):517–547. doi: 10.1079/BJN2000280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rayman M. P. Selenium . Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. Is adequate selenium important for healthy human pregnancy? [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Selenium and Carotenoids: A Report of the Panel on Dietary Antioxidants and Related Compounds . Washington, DC, USA: National Academy Press; 2000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Downs S. H., Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health . 1998;52(6):377–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hooper P., Jutai J. W., Strong G., Russell-Minda E. Age-related macular degeneration and low-vision rehabilitation: a systematic review. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology . 2008;43(2):180–187. doi: 10.3129/i08-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tara F., Rayman M. P., Boskabadi H., et al. Selenium supplementation and premature (pre-labour) rupture of membranes: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology . 2010;30(1):30–34. doi: 10.3109/01443610903267507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mesdaghinia E., Rahavi A., Bahmani F., Sharifi N., Asemi Z. Clinical and metabolic response to selenium supplementation in pregnant women at risk for intrauterine growth restriction: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Trace Element Research . 2017;178(1):14–21. doi: 10.1007/s12011-016-0911-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mokhber N., Namjoo M., Tara F., et al. Effect of supplementation with selenium on postpartum depression: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine . 2011;24(1):104–108. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.482598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tara F., Rayman M. P., Boskabadi H., et al. Prooxidant-antioxidant balance in pregnancy: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of selenium supplementation. Journal of Perinatal Medicine . 2010;38(5):473–478. doi: 10.1515/jpm.2010.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asemi Z., Jamilian M., Mesdaghinia E., Esmaillzadeh A. Effects of selenium supplementation on glucose homeostasis, inflammation, and oxidative stress in gestational diabetes: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Nutrition . 2015;31(10):1235–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jamilian M., Samimi M., Ebrahimi F. A., et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on gene expression levels of inflammatory cytokines and vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with gestational diabetes. Biological Trace Element Research . 2018;181(2):199–206. doi: 10.1007/s12011-017-1045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mao J., Bath S. C., Vanderlelie J. J., Perkins A. V., Redman C. W., Rayman M. P. No effect of modest selenium supplementation on insulin resistance in UK pregnant women, as assessed by plasma adiponectin concentration. British Journal of Nutrition . 2016;115(1):32–38. doi: 10.1017/S0007114515004067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karamali M., Dastyar F., Badakhsh M. H., Aghadavood E., Amirani E., Asemi Z. The effects of selenium supplementation on gene expression related to insulin and lipid metabolism, and pregnancy outcomes in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biological Trace Element Research . 2019:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01818-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moore M. A., Wandera R. C., Xia Y. M., Du S. H., Butler J. A., Whanger P. D. Selenium supplementation of Chinese women with habitually low selenium intake increases plasma selenium, plasma glutathione peroxidase activity, and milk selenium, but not milk glutathione peroxidase activity. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry . 2000;11(6):341–347. doi: 10.1016/S0955-2863(00)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dodge M. L., Wander R. C., Butler J. A., Du S. H., Thomson C. D., Whanger P. D. Selenium supplementation increases the polyunsaturated fatty acid content of human breast milk. The Journal of Trace Elements in Experimental Medicine . 1999;12(1):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kupka R., Mugusi F., Aboud S., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of selenium supplements among HIV-infected pregnant women in Tanzania: effects on maternal and child outcomes. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition . 2008;87(6):1802–1808. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.6.1802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sudfeld C. R., Aboud S., Kupka R., Mugusi F. M., Fawzi W. W. Effect of selenium supplementation on HIV-1 RNA detection in breast milk of Tanzanian women. Nutrition . 2014;30(9):1081–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okunade K. S., Olowoselu O. F., John‐Olabode S., et al. Effects of selenium supplementation on pregnancy outcomes and disease progression in HIV‐infected pregnant women in Lagos: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics . 2021;153(3):533–541. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Negro R., Greco G., Mangieri T., Pezzarossa A., Dazzi D., Hassan H. The influence of selenium supplementation on postpartum thyroid status in pregnant women with thyroid peroxidase autoantibodies. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism . 2007;92(4):1263–1268. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mantovani G., Isidori A. M., Moretti C., et al. Selenium supplementation in the management of thyroid autoimmunity during pregnancy: results of the “SERENA study”, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endocrine . 2019;66(3):542–550. doi: 10.1007/s12020-019-01958-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mao J., Pop V. J., Bath S. C., Vader H. L., Redman C. W., Rayman M. P. Effect of low-dose selenium on thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid function in UK pregnant women with mild-to-moderate iodine deficiency. European Journal of Nutrition . 2016;55(1):55–61. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0822-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pearce E. N. Selenium Supplementation in Pregnancy Did Not Improve Thyroid Function or Thyroid Autoimmunity. Clinical Thyroidology . 2015;27(2):30–31. doi: 10.1089/ct.2015;27.30-31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tara F., Maamouri G., Rayman M. P., et al. Selenium supplementation and the incidence of preeclampsia in pregnant Iranian women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Taiwanese Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology . 2010;49(2):181–187. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(10)60038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rayman M. P., Searle E., Kelly L., et al. Effect of selenium on markers of risk of pre-eclampsia in UK pregnant women: a randomised, controlled pilot trial. British Journal of Nutrition . 2014;112(1):99–111. doi: 10.1017/S0007114514000531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rayman M. P., Bath S. C., Westaway J., et al. Selenium status in UK pregnant women and its relationship with hypertensive conditions of pregnancy. British Journal of Nutrition . 2015;113(2):249–258. doi: 10.1017/S000711451400364X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boskabadi H., Omran F. R., Tara F., et al. The Effect of Maternal Selenium Supplementation on Pregnancy Outcome and the Level of Oxidative Stress in Neonates . Tehran, Iran: Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal (IRCMJ); 2021. https://www.sid.ir/en/Journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=179727 . [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boskabadi H., Maamouri G., Omran F. R., et al. Effect of prenatal selenium supplementation on cord blood selenium and lipid profile. Pediatrics & Neonatology . 2012;53(6):334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.