Abstract

The effects of antibiotic production on rhizosphere microbial communities of field-grown Phaseolus vulgaris were assessed by using ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis. Inoculum strains of Rhizobium etli CE3 differing only in trifolitoxin production were used. Trifolitoxin production dramatically reduced the diversity of trifolitoxin-sensitive members of the α subdivision of the class Proteobacteria with little apparent effect on most microbes.

The great majority of microorganisms in the environment remain unidentified because they are not culturable with standard techniques (2, 14, 15, 23). The phylogenetic diversity of soil bacteria observed by culture-independent methods is enormous (4, 5, 17, 22). Ribosomal intergenic spacer analysis (RISA) is used to assess microbial diversity in complex systems, as well as estimate effects of disturbance on diversity (5), such as the introduction of an antibiotic-producing bacterium into soil. To date, nothing is known about the ability of antibiotic production to affect microbial diversity in the environment from a culture-independent perspective. In this study, we assessed microbial diversity changes in the rhizosphere of bean plants following inoculation with bacterial strains that differ only in the ability to produce a narrow-spectrum peptide antibiotic, trifolitoxin (TFX).

The Rhizobium TFX production phenotype reduces the number of TFX-sensitive rhizobia in bean rhizospheres and enhances the ability of a strain to limit root nodulation by TFX-sensitive Rhizobium strains (12, 13, 18–20). By using the nearly isogenic strains of Rhizobium etli available that differ only in the presence or absence of the TFX production phenotype, we assessed the ability of the TFX production phenotype to alter microbial diversity in the rhizosphere by using RISA. As the taxonomic range of in vitro TFX sensitivity is restricted to a specific group of members of the α subdivision of the class Proteobacteria (α-Proteobacteria) (21), the specificity of the TFX action on rhizosphere microbes was estimated.

The inoculum strains used are derivatives of R. etli CE3. CE3(pT2TFXK) and CE3(pT2TX3K) are nearly isogenic, TFX-producing and -nonproducing strains, respectively (13). Culture conditions, inoculation methods, antibiotic concentrations, seed coating, bean cultivar, soil properties, and experimental design and location were described previously (12).

To amplify RISA PCR products specific to the taxonomic group of bacteria sensitive to TFX, a forward 16S ribosomal DNA (rDNA) primer referred to as RB1 (5′-TGGTGACAGTGGGCAGCG-3′) was designed. The specificity of RB1 for the TFX-sensitive bacteria was confirmed by PCR analysis with template DNA of organisms within and outside this group by using TR8 as the reverse primer (3, 11). Further evidence of RB1 specificity was obtained by using the Check Probe program from the Ribosomal Database Project (9).

Sixty-three days after planting, root sections from four plants per plot were removed from soil, placed in 40 ml of sterile water, and shaken for 30 min at 250 rpm at room temperature. Rhizosphere DNA was extracted from 1 ml of root washes by using a soil DNA extraction kit (Bio 101) and then further purified with Wizard columns (Promega). RISA-PCR was performed as described previously (5). To amplify rDNA from α-Proteobacteria sensitive to TFX, the RB1 forward primer was used. The PCR conditions used to amplify rDNA from TFX-sensitive α-Proteobacteria were 94°C for 60 s; 30 cycles of 94°C for 15 s, 58°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 25 s; and extension at 72°C for 60 s. Fragments common or specific to treatments were excised from the gel, extracted in water, and reamplified by using the RB1 and TR8 primers. The resulting 230 to 250-bp fragments were sequenced by dye termination (5). Sequences from the RISA bands were compared with all sequences in the databases by using BLAST (1).

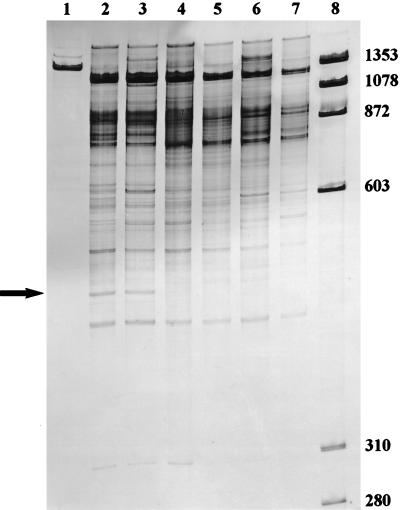

The RISA products obtained by using universal rDNA primers suggest that the microbial diversity of rhizosphere soil is immense (5) (Fig. 1). Many bands were observed in the size range of 300 to 1,400 bp. Very few differences in the overall microbial diversity were observed, regardless of the inoculum strain used (Fig. 1). However, a significant difference between the RISA patterns obtained with the uninoculated treatment and the two inoculated treatments was observed. The RISA pattern from the uninoculated rhizosphere shows a 450-bp fragment that is not present in patterns from the rhizospheres inoculated with either CE3(pT2TFXK) or CE3(pT2TX3K). This suggests that inoculation with R. etli reduces the population of the microorganism(s) represented by the 450-bp fragment, while the TFX production phenotype has little detectable effect on the overall microbial diversity.

FIG. 1.

Intergenic 16S to 23S rDNA patterns of dominant microbial populations in the rhizosphere of beans inoculated with R. etli CE3 strains that differ in TFX production in Arlington, Wis., 1997. Lanes: 1, pure culture of R. etli CE3; 2 and 3, rDNA bands from rhizosphere of uninoculated plants; 4 and 5, rDNA bands from rhizospheres inoculated with CE3(pT2TFXK) (the TFX-producing strain); 6 and 7, rDNA bands from rhizospheres inoculated with CE3(pT2TX3K) (the TFX-nonproducing strain); 8, molecular size markers. The arrow indicates a 450-bp fragment absent in R. etli treatments. Each lane represents an independent replicate. The values on the right are molecular sizes in base pairs.

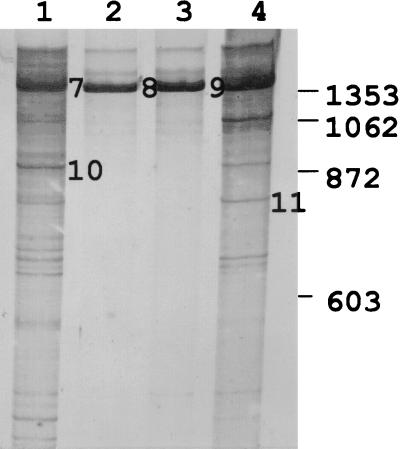

When RB1 was used for amplification, the RISA pattern was considerably less complex than that obtained with 1406F (5) (Fig. 2). The complexity decreased even more dramatically when the rhizosphere was inoculated with CE3(pT2TFXK). There was very little difference between the patterns obtained with the uninoculated treatment and the treatment inoculated with CE3(pT2TX3K) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Intergenic 16S to 23S rDNA patterns of dominant α-proteobacterial populations in the rhizosphere of beans inoculated with R. etli CE3 strains that differ in TFX production in Arlington, Wis., 1997. Lanes: 1, rDNA bands from rhizosphere of uninoculated plants; 2 and 3, rDNA bands from rhizosphere of plants inoculated with CE3(pT2TFXK) (the TFX-producing strain); 4, rDNA bands from rhizospheres of plants inoculated with CE3(pT2TX3K) (the TFX-nonproducing strain). Numbers inside the gel, to the right of bands, refer to fragments that were excised and sequenced corresponding to TFX-resistant or TFX-sensitive populations. Bands corresponding to TFX-resistant populations were identified by their presence in rhizosphere samples. Bands corresponding to TFX-sensitive populations were identified by their absence in the rhizosphere samples from the treatment containing the TFX-producing strain. Each lane represents an independent replicate. Rhizosphere DNA was isolated 63 days after inoculation. The values on the right are molecular sizes in base pairs.

A few bands from the α-proteobacterial RISA gel were excised and sequenced. Some bands were chosen that were common to all of the treatments. Others were chosen because they were not found in the rhizosphere of plants inoculated with CE3(pT2TFXK). All sequences showed very high homology to the TFX-sensitive α-Proteobacteria, consistent with the specificity of the forward primer used to amplify these fragments (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Results of sequence analysis of selected RISA bands that are labeled in Fig. 2

| rrn DNA band | Accession no. of RISA band sequence | Closest relativesa | % Identity | Accession no. of closest relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7TR | AF073476 | Rhizobium leguminosarum | 99 | D14513 |

| R. etli TAL 182 | U28939 | |||

| R. tropici IIB | X67234 | |||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | D14505 | |||

| 8TR | AF073477 | Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii | 99 | U31074 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae | U89829 | |||

| R. mongolense | U89822 | |||

| R. tropici IIB | X67234 | |||

| 9TR | AF073478 | Rhizobium sp. | 100 | AF041443 |

| Rhizobium sp. | Y10174 | |||

| R. etli TAL182 | U28939 | |||

| Rhizobium leguminosarum | X67233 | |||

| 10TS | AF073479 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens bv. 2 | 99 | D14501 |

| R. leguminosarum | X67233 | |||

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae | U29386 | |||

| R. mongolense | U89822 | |||

| 11TS | AF073480 | Agrobacterium tumefaciens bv. 2 | 98 | D14501 |

| R. leguminosarum bv. viciae | U89829 | |||

| R. tropici IIb | X67234 | |||

| R. gallicum | AF008128 |

The closest relatives of these partial rDNA sequences were identified by BLAST.

Previous studies have examined the culturable microbial community in the rhizosphere upon inoculation with an antibiotic-producing strain (7, 8, 10). All of these studies examined only the culturable microorganisms, which meant that only a small portion of the rhizosphere microbial community was examined. In addition, the effects observed on the cultured communities could not be attributed to antibiotic production, since undefined chemical mutants were used for comparison with the wild type (7, 8).

Thus, a culture-independent approach was used here to examine changes in the bean rhizosphere after inoculation with two Rhizobium strains that differ only in antibiotic production. An uninoculated treatment was also included to determine the effects of Rhizobium inoculation on the rhizosphere microbial community. This approach also examined the effects on the taxonomically defined group of TFX-sensitive microorganisms. Our results are consistent with the taxonomic range of activity of TFX, since the α-proteobacterial RISA profile was considerably altered by the TFX-producing strain, while the total microorganism RISA profile was not substantially affected (Fig. 1 and 2).

Thus, TFX production has a significant effect on TFX-sensitive bacteria in the rhizosphere of beans under agricultural conditions. This effect is not noticeable with the total microbial RISA profile, as expected, given the inability of TFX to inhibit most bacteria and given that the α-Proteobacteria are not common in soil (4, 5). Although the culture bias has been removed from this work, PCR and primer biases remain (6, 16). However, despite these potential biases, this report strongly suggests that a reduction in the diversity of α-Proteobacteria has occurred with TFX production.

Acknowledgments

Funds for this work were provided by USDA NRI grant 94-37-050767, USDA Risk Assessment Program grant 94-33120-0433, USEPA Risk Assessment Cooperative Agreement CR-822882-01-0, and University of Wisconsin-Madison College of Agricultural and Life Sciences Hatch project 5201.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schaeffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped blast and PSI-blast: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I. Fluorescently labeled, rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes in the study of microbial ecology. Mol Ecol. 1995;4:543–554. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angert E R, Clements K D, Pace N R. The largest bacterium. Nature. 1993;362:239–241. doi: 10.1038/362239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borneman J, Skroch P W, O’Sullivan K M, Palus J A, Rumjanek N, Jansen J L, Nienhuis J, Triplett E T. Molecular microbial diversity of an agricultural soil in Wisconsin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1935–1943. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.6.1935-1943.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borneman J, Triplett E W. Molecular microbial diversity in soils from eastern Amazonia: evidence for unusual microorganisms and microbial population shifts associated with deforestation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2647–2653. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.7.2647-2653.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farrelly V, Rainey F A, Stackebrandt E. Effect of genome size and rrn gene copy number on PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes from a mixture of bacterial species. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2798–2801. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2798-2801.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilbert G S, Parke J L, Clayton M K, Handelsman J. Effects of an introduced bacterium on bacterial communities on roots. Ecology. 1993;74:840–854. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kloepper J W, Schroth M N. Relationship of in vitro antibiosis of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria to plant growth and the displacement of root microflora. Phytopathology. 1981;71:1020–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J M, Woese C R. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–110. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Natsch A, Keel C, Hebecker N, Laasik E, Defago G. Influence of biocontrol strain Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 and its antibiotic overproducing derivative on the diversity of resident root colonizing pseudomonads. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;23:341–352. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Palus J A, Borneman J, Ludden P W, Triplett E W. A diazotrophic bacterial endophyte isolated from stems of Zea mays L. and Zea luxurians Iltis and Doebley. Plant Soil. 1996;186:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robleto E A, Kmiecek K, Oplinger E S, Nienhuis J, Triplett E W. Trifolitoxin production increases nodulation competitiveness of Rhizobium etli CE3 under agricultural conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2630–2633. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.7.2630-2633.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robleto E A, Scupham A J, Triplett E W. Trifolitoxin production in Rhizobium etli strain CE3 increases competitiveness for rhizosphere growth and root nodulation of Phaseolus vulgaris in soil. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:228–233. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roszak D B, Colwell R R. Survival strategies of bacteria in the natural environment. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:365–379. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.3.365-379.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Staley J T, Konopka A. Measurement of in situ activities of nonphotosynthetic microorganisms in aquatic and terrestrial habitats. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1985;39:321–346. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.39.100185.001541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Susuki M T, Giovannoni S J. Bias caused by template annealing in the amplification of mixtures of 16S rRNA genes by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:625–630. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.2.625-630.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torsvik V, Goksøyr J, Daae F L. High diversity in DNA of soil bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:782–787. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.3.782-787.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Triplett E W. Construction of a symbiotically effective strain of Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii with increased nodulation competitiveness. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:98–103. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.1.98-103.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Triplett E W. Isolation of genes involved in nodulation competitiveness from Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii T24. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:3810–3814. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Triplett E W, Barta T M. Trifolitoxin production and nodulation are necessary for the expression of superior nodulation competitiveness by Rhizobium leguminosarum bv. trifolii T24. Plant Physiol. 1987;85:335–342. doi: 10.1104/pp.85.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Triplett E W, Breil B T, Splitter G A. Expression of tfx and sensitivity to the rhizobial peptide antibiotic trifolitoxin in a taxonomically distinct group of α-proteobacteria including the animal pathogen Brucella abortus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4163–4166. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.11.4163-4166.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ueda T, Suga Y, Matsuguchi T. Molecular phylogenetic analysis of a soil microbial community in a soybean field. Eur J Soil Sci. 1995;46:415–421. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward D M, Weller R, Bateson M M. 16S rRNA sequences reveal numerous uncultured microorganisms in a natural community. Nature. 1990;345:63–65. doi: 10.1038/345063a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]