Abstract

Introduction

Our earlier analysis during the COVID-19 surges in 2020 showed a reduction in general practitioner (GP) in-person visits to residential aged care facilities (RACFs) and increased use of telehealth. This study assessed how sociodemographic characteristics affected telehealth utilisation.

Methods

This retrospective cohort consists of 27,980 RACF residents aged 65 years and over, identified from general practice electronic health records in Victoria and New South Wales during March 2020-August 2021. Residents’ demographic characteristics, including age, sex, region, and pension status, were analysed to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the associations with telehealth utilisation (telephone/video vs. in-person consultations) and with video versus telephone consultations, in mixed-effects multiple level regression models.

Results

Of 32,330 median monthly GP consultations among 21,987 residents identified in 2020, telehealth visits accounted for 17% of GP consultations, of which 93% were telephone consults. In 2021, of 32,229 median monthly GP consultations among 22,712 residents, telehealth visits accounted for 11% of GP consultations (97% by telephone). Pension holders (OR: 1.14; 95% CI: 1.10, 1.17) and those residing in rural areas (OR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.57, 1.90) were more likely to use telehealth. However, residents in rural areas were less likely to use video than telephone in GP consultations (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.29, 0.57). Results were similar in separate analyses for each COVID surge.

Discussion

Telephone was primarily used in telehealth consultations among pension holders and rural residents in RACFs. Along with the limited use of video in virtual care in rural RACFs, the digital divide may imply potential healthcare disparities in socially disadvantaged patients.

Keywords: Telehealth, telemedicine, residential aged care facilities, nursing homes, primary care, COVID-19

Introduction

Residents in aged care facilities represent one of the most vulnerable populations during the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. In Australia, as of 8 October 2021, over 13% of aged care facilities had at least one COVID-19 outbreak, affecting a workforce surge of over 4600 extra healthcare workers’ deployment involving 48,000 shifts.1 The consequent lockdowns and isolations were critical to protecting residents, aged care workers, nursing staff, and healthcare providers’ safety from contracting and further spreading the infection. However, these protective measures also largely impacted residents’ assisted living routines and regular healthcare.2 As a result, residential aged care facilities introduced severe limitations on visiting residents for both family and health professionals.

Many countries, including Australia, have expanded telehealth in clinical care since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The most significant advantage of telehealth is to facilitate safe, timely, and continuous healthcare delivery.3–5 Other benefits include cost and time efficiencies and improved care access in remote areas.4 Nevertheless, challenges have arisen, including the lack of well-equipped information technology (IT) infrastructure,6 limited computer literacy and skills,4 difficulty in performing physical examinations,4 and interactions with patients who had cognitive, visual, or hearing impairment.7 These issues are particularly prevalent in residents living in long-term care facilities. Furthermore, social disparities have been mentioned as a common barrier to optimal utilisation of telehealth.4,7

To our best knowledge, most studies on the utilisation of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic are either descriptive, qualitative surveys, or opinions. In addition, there are limited data quantifying patients’ characteristics associated with telehealth use. And these studies are among general populations and during the early phase of the pandemic.8–10 Hence, the extent to which social disparities affect telehealth utilisation in long-term care settings remains unknown.

This study assessed the association between residents’ sociodemographic characteristics and telehealth utilisation in residential aged care facilities (RACFs) in Australia. Additionally, we compared the period of each COVID surge with the period when most restrictions were lifted to assess how telehealth utilisation varied during the pandemic. The current study builds on our descriptive analysis on the observed reduction in general practitioner (GP) in-person visits to RACFs and the increasing trends of telehealth consultations during the COVID surges in 2020.11

Methods

Data source

This study is part of the project using near-real-time general practice electronic health records to assess the quality of care during the COVID-19 pandemic.12 We extracted data from general practice electronic health records stored on a secure digital health platform, Population Level Analysis & Reporting (POLAR), which at the time of this analysis (current up to 31 August 2021) draws from around 1300 general practices, in which 840 have agreed for their data to be used for de-identified research purposes in Victoria (n = 502) and New South Wales (n = 338), the two most populous states in Australia and where COVID has been the most prevalent. The POLAR data source captures de-identified patient records and primary care visits, medication prescriptions, and pathology testing and has generated several publications.13–15

For the current analysis, we extracted data from 412 general practices (146 from New South Wales, including Central and Eastern Sydney (urban) and South Western Sydney (incorporating rural areas Wingello to Bundanoon) primary health networks and 266 from Victoria, including two urban primary health networks (Eastern Melbourne and South East Melbourne) and a predominantly rural area (Gippsland). Ethics to collect and use this data source for research was obtained by the data custodian, Outcome Health, and granted by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) ethics committee (17-008). Ethics approval for the project was obtained from Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (52020675617176). This study was reported according to the items listed on the Reporting of studies Conducted using Observational Routinely Collected Data (RECORD) for observational studies using routinely collected health data.16

Study sample

Primary care is the most common healthcare service provided to geriatric patients in different countries.7 An earlier study in Australia also reports that 78% of the clinical consultations were conducted by primary care physicians in RACFs.17 Therefore, using general practice electronic health records allows studying telehealth utilisation among aged care residents. We used three criteria to identify residents, including Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) items in general practice, but billed explicitly for RACFs (Supplemental Table 1), persons aged 65 years or over, and patient records with at least one GP service billed during the study period.

Demographic characteristics

We included the following variables in our analysis: age group (65 to 69 years, 70 to 74 years, 75 to 79 years, 80-84 years, and 85 years and above), sex (male, female), regions (urban, rural),18 and state of RACF location (New South Wales or Victoria). We used pension status as a proxy to reflect income level for each resident, defined as those holding a pensioner concession card that qualifies holders for subsidised healthcare, medicines, other discounts, and payments from the Australian government.19 Socioeconomic status was adjusted as a confounder as it is based on the postcode of a RACF and, therefore, it does not necessarily reflect residents’ socioeconomic status.

General practice standard consultations

Besides the MBS items mentioned above for in-person (face-to-face) consultations, temporary telehealth (telephone or video) MBS items were included in calculating the total number of GP visits (Supplemental Table 1). Additionally, we calculated monthly visits by GPs to RACFs, using billing item number (90001), which applies to a GP's initial attendance at a facility and is billable only for the first patient seen on a visit.

Outcome measures

Telehealth utilisation was estimated as a binary variable categorised by telephone/ video consultations or face-to-face consultations. As our previous descriptive analyses have shown that video consultations occurred less frequently than telephone,11,20 we also assessed the association for video versus telephone consultations.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the median (interquartile range, IQR) for GPs’ visits to RACFs, and the proportion of telehealth consultations for telephone and video separately. To assess the associations for telehealth or video utilisation, we used mixed-effects multiple level regression models clustering at the practice level to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each demographic characteristic in a univariate and multivariate model. We conducted these analyses for the whole analytic period (March 2020 – August 2021) and separately for each COVID surge from March to May 2020 (first wave), June to September 2020 (second wave), and June to August 2021 (beginning of the third wave). We further applied a time series regression model (xtregar in Stata) to assess whether telehealth consultations varied by COVID surge in comparison with the period of no severe COVID outbreaks, using the first-order autoregression [AR(1)] structure to account for autocorrelation in the patient-level time-series panel data clustering at the general practice provider level. We also accounted for seasonality by including months in the model. In addition, sensitivity analysis was conducted among residents with records for both years. Finally, we tested interactions by having an interaction term of (year X state) and (year X region) in the multivariate regression models. The stratified analyses were conducted to account for the differences in the COVID-19 surges between the states and between urban and rural areas. We performed all analyses using Stata 16 MP (StataCorp, TX., USA). Statistical significance was set at two-sided and determined by α <0.05.

Results

Sample selection and GP consultations

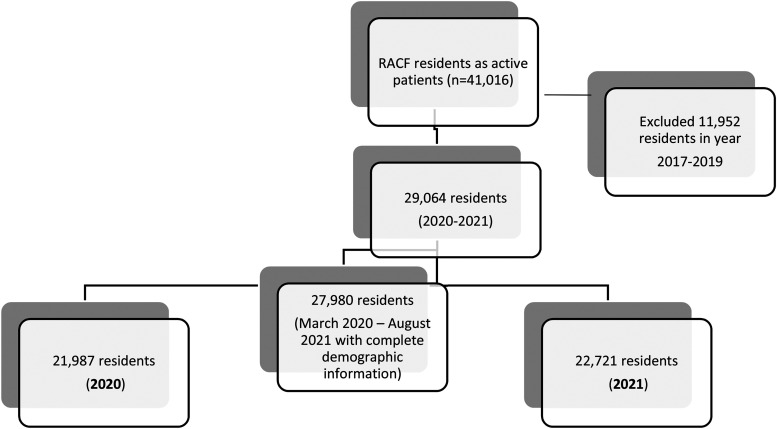

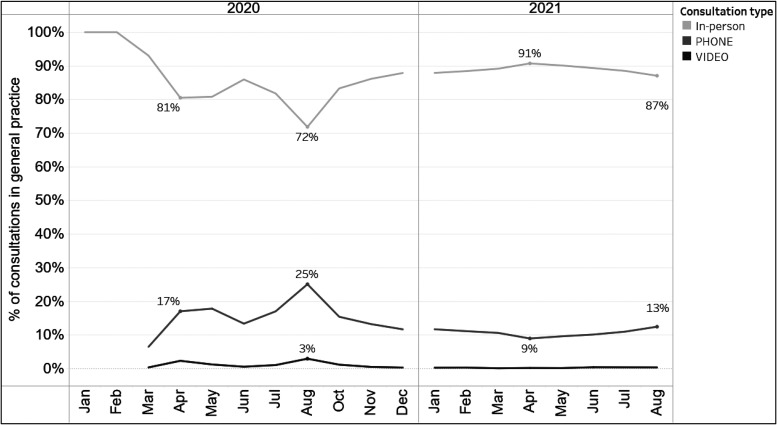

Figure 1 describes the process for the sample selection. We included 27,980 eligible individuals during 1 March 2020 to 31 August 2021. Among these residents, 21,987 were identified in 2020 with 32,229 (31,648, 33445) [median (IQR)] monthly GP visits recorded and 22,712 residents with 37,339 (34327, 38162) [median (IQR)] monthly GP visits recorded in 2021. Telehealth consultations accounted for 17% (14%, 18%) (median, IQR) of the total GP visits for 2020 and 11% (10%, 12%) for 2021. Figure 2 describes the percentage of each type of consultation. Of note, over 90% of the telehealth consultations were conducted by telephone (93% for 2020 and 97% for 2021). Furthermore, GPs’ in-person visits to RACFs decreased from 2019 to 2020. The median (IQR) for monthly visits reduced from 4311 (4127, 4925) visits in 2019 to 4209 (3994, 4259) in 2020 but returned to 4374 (4320, 4506) in 2021 up to August

Figure 1.

Study sample selection.

Figure 2.

Proportion for each consultation type in general practice consultations in residential aged care facilities from March 2020 to August 2021.

Residents’ demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. The distribution for age group, sex, pension status, region, and state are comparable between 2020 and 2021. For both years, over 60% of the residents were aged 85 and over, two-thirds were women, and over 79% were pension holders or living in urban areas. Over 70% of the study sample resided in Victoria.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of aged care residents by year during the study period of March 2020 to August 2021.

| 2020 | 2021 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 21,987 | n = 22,712 | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age group (year) | ||||

| 65 – 69 | 859 | 3.9 | 858 | 3.8 |

| 70 – 74 | 1603 | 7.3 | 1708 | 7.5 |

| 75 – 79 | 2331 | 10.6 | 2476 | 10.9 |

| 80 – 84 | 3676 | 16.7 | 3946 | 17.4 |

| 85 + | 13,518 | 61.5 | 13,724 | 60.4 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 14,343 | 65.2 | 14,832 | 65.3 |

| Male | 7644 | 34.8 | 7880 | 34.7 |

| Pension status | ||||

| Not on pension | 4224 | 19.2 | 4701 | 20.7 |

| On pension | 17,763 | 80.8 | 18,011 | 79.3 |

| Region | ||||

| Urban areas | 17,374 | 79.0 | 17,905 | 78.8 |

| Rural areas | 4613 | 21.0 | 4807 | 21.2 |

| State | ||||

| New South Wales | 5849 | 26.6 | 5873 | 25.9 |

| Victoria | 16,138 | 73.4 | 16,839 | 74.1 |

The association between demographic characteristics and the utilisation of telehealth versus face-to-face consultations is described in Table 2. In the multivariate models, residents were 33% (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.65, 0.68) less likely to use telehealth in 2021 than in 2020. However, pension holders or those residing in rural areas had 14% (OR 1.14; 95% CI: 1.10, 1.17) and 72% (OR: 1.72; 95% CI: 1.57, 1.90) more likely of using telehealth, respectively. We also found an inverse relationship between age group and telehealth utilisation, in that the older the age, the less likely residents used telehealth. However, no difference was found between men and women or states.

Table 2.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the association between demographic characteristics and telehealth (phone and videoconferencing) utilisation during March 2020 to August 2021.

| Telehealth use, % | Univariate model a | Multivariate model b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||

| 2020 | 29.1 | Ref | Ref |

| 2021 | 21.0 | 0.63 (0.62, 0.64) | 0.67 (0.65, 0.68) |

| Age group (year) | |||

| 65-69 | 29.4 | Ref | Ref |

| 70 – 74 | 26.7 | 0.96 (0.90, 1.03) | 0.96 (0.9, 1.03) |

| 75 – 79 | 26.7 | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) | 0.87 (0.82, 0.93) |

| 80 – 84 | 26.9 | 0.86 (0.81, 0.92) | 0.86 (0.81, 0.91) |

| 85 + | 24.3 | 0.70 (0.67, 0.75) | 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 25.3 | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 25.4 | 1.06 (1.04, 1.08) | 1.02 (1.0, 1.04) |

| Pension status | |||

| Not on pension | 26.8 | Ref | Ref |

| On pension | 25.0 | 1.16 (1.12, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.17) |

| Region | |||

| Urban | 24.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 27.1 | 1.31 (1.20, 1.43) | 1.72 (1.57, 1.90) |

| State | |||

| NSW | 22.8 | Ref | Ref |

| Victoria | 26.1 | 1.30 (0.79, 1.53) | 1.08 (0.77,.151) |

Analyses were based on 238,812 monthly general practice consultation records

Univariate model without adjusting for any other covariates

Multivariate model after adjusting for Year (2020, 2021), Month, age-groups (65-69 y, 70-74 y, 75-79 y, 80-84 y, and 85 y + ), sex (female, male), socioeconomic status based on postcodes for aged care facilities by quintile, pension status (yes, no), region (urban, rural areas), and state (New South Wales, Victoria).

We found consistent results for each COVID-19 surge. In particular, pension holders and residents living in rural areas had higher odds of using telehealth than face-to-face consultations (Supplemental Table 2). Additionally, during the second COVID-19 surge, when Victoria had more than 100 days in lockdown between June and September 2020, telehealth access was almost two-fold compared to New South Wales (Supplemental Table 2). These results were further confirmed in the time series regression models. Compared to the period with no severe outbreaks (October 2020-May 2021), the first (March-May 2020, outbreaks in New South Wales, particularly) and second waves (June – September 2020, outbreaks in Victoria, particularly) were both positively related to higher telehealth consultations, with the coefficient (95% CI) as 0.04 (0.002, 0.04; p < 0.0001) and 0.09 (0.002, 0.09; p < 0.001), respectively. For the beginning of the 3rd wave (June – Aug 2021), the association with telehealth consultations was marginal (0.01; 0.002, 0.01; p < 0.0001).

Associated factors for video versus telephone consultations are described in Table 3. Compared to 2020, residents were less likely to use video visits in 2021. Strikingly, residents living in rural areas were 59% less likely (OR: 0.41; 95% CI: 0.29, 0.57) to use video than telephone consultations. No associations were found for other demographic variables.

Table 3.

Odds ratios (95% confidence intervals) for the association between demographic characteristics and videoconference consultations during March 2020 to August 2021.

| Videoconferencing use (%) | Univariate model a | Multivariate model b | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | |||

| 2020 | 7.9 | Ref | Ref |

| 2021 | 3.5 | 0.43 (0.39, 0.47) | 0.37 (0.33, 0.41) |

| Age group (year) | |||

| 65-69 | 5.6 | Ref | Ref |

| 70 – 74 | 4.6 | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08) | 0.8 (0.61, 1.03) |

| 75 – 79 | 5.7 | 1.12 (0.88, 1.42) | 1.13 (0.89, 1.44) |

| 80 – 84 | 6.1 | 1.04 (0.83, 1.31) | 1.03 (0.82, 1.29) |

| 85 + | 6.6 | 1.22 (0.99, 1.51) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.49) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 6.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 5.7 | 0.91 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.94 (0.86, 1.02) |

| Pension status | |||

| Not on pension | 5.4 | Ref | Ref |

| On pension | 6.4 | 1.05 (0.86, 1.17) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) |

| Region | |||

| Urban | 6.3 | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 6.0 | 0.46 (0.33, 0.63) | 0.41 (0.29, 0.57) |

| State | |||

| NSW | 3.5 | Ref | Ref |

| Victoria | 7.0 | 1.28 (0.46, 2.44) | 1.49 (0.77, 2.9) |

Analysis was based on 60,444 monthly phone and videoconferencing consultations in general practice

Univariate model without adjusting for any other covariates

Multivariate model after adjusting for Year (2020, 2021), Month, age-groups (65-69 y, 70-74 y, 75-79 y, 80-84 y, and 85 y + ), sex (female, male), socioeconomic status based on postcodes for aged care facilities by quintile, pension status (yes, no), region (urban, rural areas), and state (New South Wales, Victoria).

We found similar results using records available for both years among 17,986 residents (211,107 monthly GP consults; 54,856 monthly telehealth consultations). For example, pension holders had 13% higher odds of using telehealth (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.09, 1.16). Moreover, residents living in rural areas had 68% higher odds of using telehealth (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.51, 1.87), while they were less likely to have video consultations (OR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.26, 0.58) during the pandemic.

Significant interactions were identified between year and state (p for interaction < 0.001) and between year and region (p for interaction <0.03). For example, pension holders living in rural areas had 40% (OR: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.31, 1.50) higher odds of having telehealth consultations than 9% (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 1.05, 1.12) higher odds in urban areas. In addition, residents in New South Wales rural areas had over two-fold the likelihood of attending a telehealth consultation (OR: 2.85; 95% CI: 1.90, 4.28) than those in Victoria (OR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.54, 1.88).

Discussion

In this retrospective cohort of aged care residents followed from the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic until August 2021, we found that telehealth utilisation in residential aged care facilities corresponded to the severity of the COVID-19 situation in New South Wales and Victoria in Australia. Notably, telephone was the predominant mode in rural residents and pension holders in primary care access during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, video usage in GP access was poor in rural aged care facilities. These results may imply potential healthcare inequalities among pension holders and those residing in rural areas where healthcare resources are limited.

Our results are consistent with the existing studies that quantified demographic characteristics of telehealth utilisation during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, in a cohort of over 1000 US patients in the department of head and neck surgery, those who were in the lower first and second quartiles of median household income, or those who used Medicaid, had no insurance, or had other public insurance were more likely to complete a telephone visit.10 Another study of patients from an academic healthcare system also reported an association between lower household income and fewer video visits.9 For both US studies, the analytic period covered from March to May 2020.9,10 Other studies before the COVID-19 pandemic also suggest that telephone visits were used more often than the video mode,21 and that patients over 65 years had 30%-50% lower odds of using telehealth21,22 or video visits across various clinical conditions.9

We found over 90% of the telehealth consultations occurred by telephone, yet the highest usage of telehealth at 28% was found during the prolonged lockdowns in Victoria in August 2020. These data suggest the preference for in-person care among aged care residents.11 Consistent with our findings, an Australian survey in the general population found that although 56% of the respondents aged 65 and above were comfortable using telehealth (the lowest proportion among respondents aged 18 years and above), 84% (the highest number than other age groups) preferred face-to-face consultations.23 Other reasons that may hamper telehealth usage include patients and care providers’ limited knowledge, literacy, and capacity to operate telehealth7 and logistics such as increased sanitation of devices by nursing staff.24 Given that aged care residents often have physical disabilities such as visual, hearing, or cognitive impairment, improving devices and technologies suitable to meet residents’ needs has been recommended to ensure optimal utilisation and continuity of telehealth.25

Furthermore, our findings raise a potential issue of social inequalities in care access in aged care settings, as we found consistent results showing pensioners (holding health care cards)26,27 and those living in rural areas28 were more likely to use telephone as a predominant modality in care access in analyses across different periods. In a nutshell, telehealth can reduce inequalities and improve the quality of care in remote and marginalised communities if the IT infrastructure and devices are equipped to access care virtually.7,29,30 However, given the convenience and low cost, telephone consultations are often the most common means in clinical services, especially among low-income and socially disadvantaged9,1010.,21,22 Hence, this digital divide may reveal the gaps in equipment, internet connection, and paid software to access virtual care.

It should be noted that residential aged care facilities, funded by both the Australian Government and contributions from individual residents, are required to provide a standard level of care and services to their residents. However, residents may personalise their services to an upgrade such as a hotel-type service.31 Hence, some residents living in a more equipped facility or environment may opt to have more in-person care when possible or use videoconferencing instead of telephone consults. Other factors, including those at the GP and facility levels, can also play a role in telehealth utilisation. Future research is needed to investigate the granularity and nuance from findings in this work, including basic computer literacy, IT infrastructure, staff capacity, bed size, location, management of the COVID situation at the facility level, and enablers and barriers of using videoconferencing at the GP level.

Strengths and limitations

This study used a large sample to evaluate care delivery modes and their utilisation across the most extended period during the COVID-19 pandemic in aged care facilities using electronic health records in general practice. We found consistent results from multiple analyses to improve the confidence of the study sample identified from the data source. A limitation is the lack of coded diagnosis of health conditions, which limited our ability to assess the use of telehealth for specific health conditions. Despite the complexity of MBS billing items in telehealth (video/phone) that were introduced during the study time frame, there are currently no telehealth MBS items designated to aged care residents. Hence, the extra billing items can further incentivise GPs to deliver telehealth more efficiently in aged care facilities. Another limitation is that pension holders may include those on partial or short-term pensions, resulting in potential misclassification of those on full support. However, these misclassifications are likely non-differential and potentially underestimate the observed results. Finally, we recognise the limitation to assess factors at the GP level or the facility level for telehealth utilisation. However, this is out of the scope of the current study.

Conclusion and implications

Our study suggests that the utilisation of telehealth services in general practice corresponded to the COVID-19 severity in residential aged care facilities. Yet, as over 90% of telehealth were telephone visits, video usage was minimal. Given that face-to-face consultations were the majority of the GP consultations and likely the preferred choice of care in aged care settings, the digital divide between pension holders and non-holders and those living in and outside urban areas may highlight potential healthcare inequalities. Our data support continuing efforts and increased funding and support from the federal and state governments to optimise the utilisation of telehealth in the aged care sector, especially in rural areas and in socially disadvantaged patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre (DHCRC).

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Digital Health Cooperative Research Centre (DHCRC-0118), Australia,

ORCID iD: Zhaoli Dai https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0809-5692

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Australian Government Department of Health. COVID-19 outbreaks in Australian residential aged care facilities. In: Australian Government Department of Health. The Australian Government, 2021, pp.1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert GL. COVID-19 in a sydney nursing home: a case study and lessons learned. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 393–396e391. 2020/10/11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajizadeh A, Monaghesh E. Telehealth services support community during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran: activities of ministry of health and medical education. Inform Med Unlocked 2021; 24: 100567. 2021/04/13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alipour J, Hayavi-Haghighi MH. Opportunities and challenges of telehealth in disease management during COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Appl Clin Inform 2021; 12: 864–876. 2021/09/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monaghesh E, Hajizadeh A. The role of telehealth during COVID-19 outbreak: a systematic review based on current evidence. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 1193. 2020/08/03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seifert A, Batsis JA, Smith AC. Telemedicine in long-term care facilities during and beyond COVID-19: challenges caused by the digital divide. Front Public Health 2020; 8: 601595. 20201026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doraiswamy S, Jithesh A, Mamtani R, et al. Telehealth use in geriatrics care during the COVID-19 pandemic-A scoping review and evidence synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(4): 1755. DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18041755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiao V, Chandereng T, Lankton RL, et al. Disparities in telemedicine access: a cross-sectional study of a newly established infrastructure during the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Clin Inform 2021; 12: 445–458. 2021/06/10. DOI: 10.1055/s-0041-1730026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, et al. Patient characteristics associated with telemedicine access for primary and specialty ambulatory care during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2031640. 2020/12/30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darrat I, Tam S, Boulis M, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in patient use of telehealth during the coronavirus disease 2019 surge. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021; 147: 287–295. 2021/01/15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dai Z, Saffi Franco G., Datta S., et al. . The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on general practice consultations in residential aged care facilities. 2021.

- 12.Georgiou A, Li J, Pearce C, et al. COVID-19: protocol for observational studies utilizing near real-time electronic Australian general practice data to promote effective care and best-practice policy-a design thinking approach. Health Res Policy Syst 2021; 19: 122. 2021/09/09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sezgin G, Monagle P, Loh TP, et al. Clinical thresholds for diagnosing iron deficiency: comparison of functional assessment of serum ferritin to population based centiles. Sci Rep 2020; 10: 18233. 2020/10/28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan J, Hawes L, Turner L, et al. Antimicrobial prescribing for children in primary care. J Paediatr Child Health 2019; 55: 54–58. 2018/07/25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turner LR, Pearce C, Borg M, et al. Characteristics of patients presenting to an after-hours clinic: results of a MAGNET analysis. Aust J Prim Health 2017; 23: 294–299. 2017/01/12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benchimol EI, Smeeth L, Guttmann A, et al. The REporting of studies conducted using observational routinely-collected health data (RECORD) statement. PLoS Med 2015; 12: e1001885. 2015/10/07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray LC, Edirippulige S, Smith AC, et al. Telehealth for nursing homes: the utilization of specialist services for residential care. J Telemed Telecare 2012; 18: 142–146. 2012/03/01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Department of Health. Modified monash model. The Australian Government, 2019.

- 19.Services Autralia. Pensioner Concession Card, https://www.servicesaustralia.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/pensioner-concession-card(2021, accessed October 22 2021).

- 20.Hardie R-A, Sezgin G, Dai Z, et al. The uptake of GP telehealth services during the COVID-19 pandemic. In: COVID-19 General practice snapshot. Sydney: Macquarie University, 2020, Issue 1, pp.1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer SH, Ray KN, Mehrotra A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of telehealth utilization in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e2022302. 2020/10/27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed ME, Huang J, Graetz I, et al. Patient characteristics associated with choosing a telemedicine visit vs office visit with the same primary care clinicians. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3: e205873. 2020/06/26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Care Side. Will seniors embrace telemedicine? Survey says, it’s complicated. https://www.thecareside.com.au/post/will-seniors-embrace-telemedicine/(2021, accessed 10 November 2021).

- 24.Lester PE, Holahan T, Siskind D, et al. Policy recommendations regarding skilled nursing facility management of coronavirus 19 (COVID-19): lessons from New York state. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2020; 21: 888–892. 2020/07/18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seifert A, Cotten SR, Xie B. A double burden of exclusion? Digital and social exclusion of older adults in times of COVID-19. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2021; 76: e99 − e103. 2020/07/17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harmer J. Pension review background paper. In: Department of families H, community services and indigenous affairs (ed.). Barton, ACT 2600: Commonwealth of Australia, 2008, 107. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones G, Savage E., Gool KV. The distribution of household health expenditures in Australia. Econ Rec 2008; 84: S99 − S114. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith KB, Humphreys JS, Wilson MG. Addressing the health disadvantage of rural populations: how does epidemiological evidence inform rural health policies and research? Aust J Rural Health 2008; 16: 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wade V, Stocks N. The use of telehealth to reduce inequalities in cardiovascular outcomes in Australia and New Zealand: a critical review. Heart Lung Circ 2017; 26: 331–337. 20161130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaw J, Brewer LC, Veinot T. Recommendations for health equity and virtual care arising from the COVID-19 pandemic: narrative review. JMIR Form Res 2021; 5: e23233. 20210405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.My Aged Care; The Australian Government. Aged care homes. 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.