Abstract

We characterized the biosynthesis of indole-3-acetic acid by the mycoherbicide Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. Auxin production was tryptophan dependent. Compounds from the indole-3-acetamide and indole-3-pyruvic acid pathways were detected in culture filtrates. Feeding experiments and in vitro assay confirmed the presence of both pathways. Indole-3-acetamide was the major pathway utilized by the fungus to produce indole-3-acetic acid in culture.

Soon after the discovery of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in higher plants, auxin activity was also detected in fungi (8); however, IAA biosynthetic pathways were identified in only a few fungi (7, 14). Although high IAA levels are often found in diseased plants, the role of IAA in fungus-plant interactions has not been determined (9).

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene causes anthracnose disease on Aeschynomene virginica, a noxious weed which infests rice and soybean fields in North America. C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene is registered as a weed biocontrol agent (mycoherbicide) and has been used as a commercial formulation (Collego) to control A. virginica (4, 15). Detailed study of the biology and pathogenic nature of this fungus is essential for the development of improved mycoherbicide formulations, e.g., by combination with synergistic agents or by genetic engineering of the fungus. Our objectives were to characterize the in vitro production of IAA by C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene and to identify the IAA-biosynthetic pathways and assess their contributions to IAA production.

We measured IAA production by 18 isolates of four Colletotrichum species that are pathogens of six different host plants. The strains used in this study included C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene 3.1.3, 5a.2, Ark 23-1, Clar 5a-1, 3-4-29, Hun 12a-1, Hyr 7-1, Keo 16-1, Min 8a-1, and Ree 6-1, isolated from northern jointvetch (Aeschynomene virginica); C. coccodes 598, isolated from velvetleaf (Abutilon theofrasti); C. gloeosporioides AS-9, NRB-24D, 31-1A, and 33-1A, isolated from avocado; C. gloeosporioides NC-131, isolated from apple; C. acutatum 106A, isolated from strawberry; and C. lindemuthianum BA-10, a pathogen of beans. All isolates were stored in 20% glycerol at −70°C and cultured on Emerson’s YpSs solid medium (6). Growth in liquid culture was conducted in 250-ml flasks containing 50 ml of either Emerson’s YpSs medium, Czapek Dox medium (3 g of NaNO3/liter, 0.5 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O/liter, 0.5 g of KCl/liter, 55 mg of FeSO4/liter, 30 g of sucrose/liter, 1 g of KH2PO4/liter), or pea juice (900 g of frozen peas cooked in 1.6 liters of water and then filtered). All media were supplemented with 100 μg of chloramphenicol or ampicillin/ml. Each flask was inoculated with agar cubes taken from the edge of a 5-day-old colony. The flasks were placed on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) and incubated in darkness at 28°C. Three separate flasks were used for each treatment, and the experiments were repeated at least three times.

Indoles were extracted with ethyl acetate and analyzed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) with silica gel 60 F254 plates (Merck). Chloroform-methanol-water (85:14:1) was the primary solvent used for analysis. Additional solvents were used for separating particular bands and confirming the identities of compounds. After development, the plates were dried, sprayed with van Urk-Salkowski reagent (5), and heated to 90°C for 10 min. The Rfs and colors of the bands were compared with the Rfs and colors of standard indoles. The identities of the indolic metabolites were verified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis on a Varian Saturn 2000 mass spectrometer by standard procedures. For quantification, known quantities of IAA, indole-3-acetamide (IAM), and tryptophol (TOL) were loaded on TLC plates and the plates were developed as described above. The plates were scanned with a Pharmacia-Biotech Image-Master DTS densitometer, the optical density per millimeter2 of each spot was determined, and a linear regression was performed for each standard compound with the ImageMaster 1D software package. A linear regression line (r2 > 0.99) was obtained over the range 1 to 20 μg for all three compounds. The standard curves were used for calculating the quantities of TOL, IAA, and IAM in the medium samples.

IAA was produced by all 18 isolates examined. The amount of IAA produced varied among the species, ranging from 2 to 32 μg of IAA per ml of culture. Strains of C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene produced larger amounts of IAA than strains of the other species. IAA biosynthesis was further characterized in C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene by using isolate 3.1.3. The fungus was grown in three different media, and indoles were extracted from the culture filtrates. Differences were observed in the amount of mycelium and in the types and amounts of the indoles that accumulated in the three media. These differences were also time dependent, e.g., the observed changes in the amount of IAM were stronger in pea juice than in Czapek Dox medium.

A number of indoles were identified, including IAA, IAM, TOL, indole-3-lactic acid (ILA), and indole-3-carboxylic acid (ICA). The identities of all five compounds were confirmed by GC-MS analysis. The presence of these metabolites in the culture filtrates suggested that two IAA biosynthetic pathways that use tryptophan as a precursor may exist in this fungus: the IAM pathway, implicated by IAM, and the indole-3-pyruvic acid (IPA) pathway, implicated by TOL and ILA (1). ICA is known to be a degradation product of IAA in plants (12).

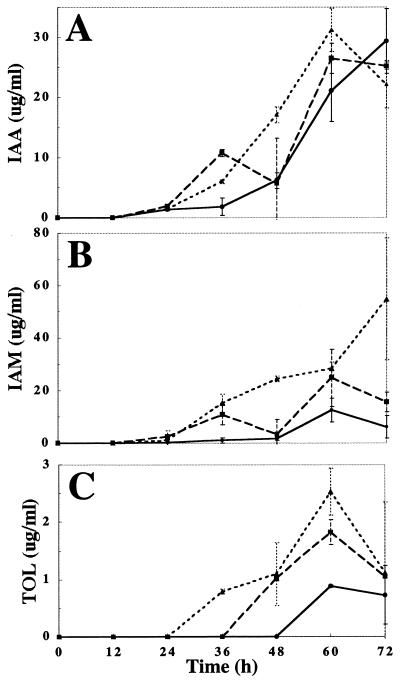

To test the importance of tryptophan as a precursor for IAA biosynthesis, the fungus was grown in Czapek Dox medium supplemented with 0, 1, 2, or 5 mM tryptophan and indolic compounds were extracted from the medium. No IAA or any other indoles were detected in the absence of tryptophan, while in the presence of tryptophan IAA accumulated to high levels (Fig. 1). The amounts of IAA, IAM, and TOL increased with increasing tryptophan concentrations (Fig. 1), providing further support for the idea that IAA biosynthesis is tryptophan dependent.

FIG. 1.

IAA biosynthesis in C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene is tryptophan dependent. Isolate 3.1.3 was grown in Czapek Dox medium supplemented with tryptophan in the beginning of the experiment. Indoles were extracted and analyzed by TLC and IAA (A), IAM (B), and TOL (C) levels were determined by densitometry. •, 1 mM tryptophan; ■, 2 mM tryptophan; ▴, 5 mM tryptophan. No indoles were detected without tryptophan in the medium (data not shown). The error bars represent 1 standard deviation from the mean.

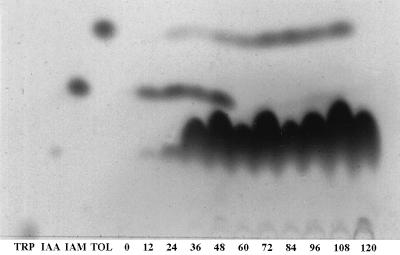

The level and nature of indoles in the culture medium changed with time. Under most conditions, IAM accumulated to high levels during the first 36 to 48 h and then its level declined until it disappeared from the medium (Fig. 2). In contrast TOL was detected in the medium at a later stage and its level increased as the culture aged (Fig. 2). Tryptophan monooxygenase and IAM hydrolase activities were higher in mycelial samples after 24 and 48 h of growth than after 72 h (data not shown). These results show that IAA biosynthesis is tryptophan dependent and suggest that under these conditions the IAM pathway contributes to IAA biosynthesis at an earlier stage while the IPA pathway may be activated only later.

FIG. 2.

Changes in IAA metabolism over time. C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene was grown in pea juice medium plus 2 mM tryptophan. Samples (15 ml) were removed every 12 h, extracted with ethyl acetate, and analyzed by TLC. Note the disappearance of the IAM band after 48 h and the accumulation of TOL. The numbers below the lanes represent the time in hours.

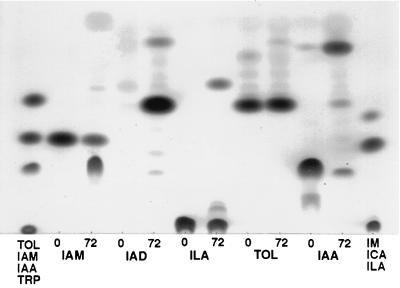

We conducted feeding experiments with different precursors to determine if the fungus could synthesize IAA from metabolites of the IAM and IPA pathways. When only IAM was added to the medium, IAA accumulated to high levels, while the IAM levels decreased with time (Fig. 3), showing that IAM is indeed essential for IAA biosynthesis in C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene. No other indolic compounds were detected, indicating that IAM serves as a precursor only for this single metabolic route. Growing the fungus in medium containing indole-3-acetaldehyde (IAD) resulted in the production of high levels of TOL as well as low levels of IAA (Fig. 3). TOL and ILA were stable under the assay conditions, with no conversion to IAA detected. When IAA was added to the medium it was partially degraded by the fungus to TOL (Fig. 3). Additional, unidentified bands were detected, most of which also were found in uninoculated control medium. The enzymatic conversion of IAA to TOL is a new observation which has apparently not been reported previously and requires further investigation.

FIG. 3.

Metabolism of IAM, TOL, ILA, and IAA. Fungi were grown in Czapek Dox medium supplemented with 1 mM of the different precursors as indicated at the bottom of the plate. Indoles were extracted every 24 h and analyzed by TLC. Only extracts from 24 (○) and 72 h are shown. TRP, tryptophan.

Low levels of IAA were produced when either IAD or ILA was used as a precursor for in vitro assay with fungal protein extracts (data not shown). No IAA was found in the controls, indicating that IAA was produced from IAD and ILA by enzymes of the IPA pathway, e.g., IPA decarboxylase and IAD dehydrogenase. When only TOL was included in the assay, no IAA was produced (data not shown). The low IAA levels could result from low-level expression of genes encoding the enzymes of the IPA pathway or from suboptimal conditions of the assay. It is also possible that the metabolism of these compounds is only partly related to IAA biosynthesis, as was found in the yeast Saccharomyces uvarum, in which TOL but not IAA is produced from IAD (13).

We have shown that both the IAM and IPA IAA biosynthetic pathways exist in C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene and contribute to high-level production of IAA in culture. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the IAM pathway has been reported in fungi. Differences were observed in the expressions of the two pathways during the growth of the fungus. Differences in activity of the IAM and IPA pathways were recently reported in Erwinia herbicola. In this phytopathogenic bacterium, the IPA pathway is expressed during the saprophytic stage of growth on the leaf surface while genes of the IAM pathway are more active after penetration of the bacterium into the leaf (10).

Although in planta production of IAA by the fungus has not been determined, there is reason to believe that IAA may be involved in fungal pathogenicity. Plant-pathogenic bacteria, such as Pseudomonas, Erwinia, and Agrobacterium, all produce IAA, and disrupting IAA biosynthesis genes in these organisms may severely reduce pathogenicity (2, 3, 11). Some of the symptoms caused by C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene, e.g., epinasty and leaf deformation, are mimicked by exposing plants to IAA. The IAA levels produced by C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene in vitro should be sufficient to evoke these responses if they are also produced in planta. The identification of the enzymatic reactions involved in IAA biosynthesis provides a basis for the cloning of IAA biosynthesis genes from C. gloeosporioides f. sp. aeschynomene and determination of the role IAA may play in fungus-plant interaction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant 525/95 from the Israel Academy of Sciences.

We thank Dave TeBeest and Stanley Freeman for fungal isolates, Naomi Agur for technical assistance, and Marina Cherniak for technical help with GC-MS analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bandurski R S, Cohen J D, Slovin J P, Renecke D M. Auxin biosynthesis and metabolism. In: Davies P, editor. Plant hormones: physiology, biochemistry, and molecular biology. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 39–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Comai L, Kosuge T. Cloning and characterization of iaaM, a virulence determinant of Pseudomonas savastanoi. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:40–46. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.1.40-46.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costacurta A, Vanderleyden J. Synthesis of phytohormones by plant-associated bacteria. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:1–18. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daniel J T, Templeton G E, Smith R J, Fox W T. Biological control of northern jointvetch in rice with an endemic fungal disease. Weed Sci. 1973;21:303–307. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ehmann A. The van Urk-Salkowski reagent—a sensitive and specific chromogenic reagent for silica gel thin-layer chromatographic detection and identification of indole derivatives. J Chromatogr. 1977;132:267–276. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)89300-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Emerson R. Mycological organization. Mycologia. 1958;50:589–621. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Furukawa T, Koga J, Takashi A, Kishi K, Syono K. Efficient conversion of l-tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid and/or tryptophol by some species of Rhizoctonia. Plant Cell Physiol. 1996;37:899–905. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruen H E. Auxins and fungi. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1959;10:405–441. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Issac S. Fungal plant interactions. London, United Kingdom: Chapman & Hall; 1992. pp. 235–237. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manulis S, Chesner-Haviv A, Brandl M T, Lindow S E, Barash I. Differential involvement of indole-3-acetic acid biosynthetic pathways in pathogenicity and epiphytic fitness of Erwinia herbicola pv. gypsophilae. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1998;11:634–643. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1998.11.7.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manulis S, Valinski L, Gafni Y, Hershenhorn J. Indole-3-acetic acid biosynthetic pathways in Erwinia herbicola in relation to pathogenicity on Gypsophila paniculata. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 1991;39:161–171. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sagee O, Riov J. Ethylene enhanced catabolism of [14C]indole-3-acetic acid to indole-3-carboxylic acid in citrus leaf tissue. Plant Physiol. 1990;92:54–60. doi: 10.1104/pp.92.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin M, Shinguu T, Sano K, Umezawa C. Metabolic fates of l-tryptophan in Saccharomyces uvarum. Chem Pharm Bull. 1991;39:1792–1795. doi: 10.1248/cpb.39.1792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosa M M E, Guevara L F, Martinez J V M, Paredes L O. Production of indole-3-acetic acid by mutant strains of Ustilago maydis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;48:726–729. [Google Scholar]

- 15.TeBeest D O, Templeton G E. Commercialization of Collego: an industrialist’s view. Weed Sci. 1986;34:24–25. [Google Scholar]