Abstract

Objective

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the effectiveness and safety of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV.

Methods

Databases (PubMed, Embase and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials) were searched up to 5 July 2020. Search terms for ‘HIV’ were combined with terms for ‘PrEP’ or ‘tenofovir/emtricitabine’. RCTs were included that compared oral tenofovir-containing PrEP to placebo, no treatment or alternative medication/dosing schedule. The primary outcome was the rate ratio (RR) of HIV infection using a modified intention-to-treat analysis. Secondary outcomes included safety, adherence and risk compensation. All analyses were stratified a priori by population: men who have sex with men (MSM), serodiscordant couples, heterosexuals and people who inject drugs (PWIDs). The quality of individual studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool, and the certainty of evidence was assessed using GRADE.

Results

Of 2803 unique records, 15 RCTs met our inclusion criteria. Over 25 000 participants were included, encompassing 38 289 person-years of follow-up data. PrEP was found to be effective in MSM (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.1 to 0.61; absolute rate difference (RD) −0.03, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.05), serodiscordant couples (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.46; RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.02) and PWID (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.92; RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.00 to −0.01), but not in heterosexuals (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.29). Efficacy was strongly associated with adherence (p<0.01). PrEP was found to be safe, but unrecognised HIV at enrolment increased the risk of viral drug resistance mutations. Evidence for behaviour change or an increase in sexually transmitted infections was not found.

Conclusions

PrEP is safe and effective in MSM, serodiscordant couples and PWIDs. Additional research is needed prior to recommending PrEP in heterosexuals. No RCTs reported effectiveness or safety data for other high-risk groups, such as transgender women and sex workers.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017065937.

Keywords: epidemiology, HIV & AIDS, public health, infectious diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted of the efficacy and safety of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to prevent HIV following best practice guidelines (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework).

Observational studies were excluded from this review, and as such, PrEP effectiveness may be lower in real-world settings.

Change in sexual behaviour, or ‘risk compensation’, is difficult to ascertain based on RCT evidence alone.

Due to substantial variation in adherence across studies, findings should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

While the incidence of HIV has declined worldwide over the past decade, 1.5 million new HIV infections occurred in 2020,1 highlighting the ongoing need for new and effective HIV prevention initiatives. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a novel biomedical form of HIV prevention method whereby oral antiretrovirals (most commonly a combination of tenofovir and emtricitabine (FTC)) are taken by individuals at high risk of HIV acquisition to prevent infection. PrEP aims to complement the existing arsenal of HIV prevention strategies, such as the promotion of safer sex practices, treatment as prevention and postexposure prophylaxis after sexual exposure.

In 2014, the WHO recommended offering PrEP to men who have sex with men (MSM),2 based on a 2010 trial that demonstrated the effectiveness in this group.3 Subsequently, in 2015, they broadened the recommendation to include anyone at substantial risk of HIV infection (defined as risk of 3 per 100 person-years in the absence of PrEP),4 based on further evidence of the acceptability and effectiveness in other populations. While the success of early PrEP studies in MSM was replicated in the years that followed,5 6 uncertainty still exists in other key populations. Many initial studies that failed to demonstrate effectiveness were plagued by poor adherence, such as those that enrolled heterosexual women.7 Also, of major concern to public health officials and policy-makers is the potential occurrence of ‘risk compensation’ in PrEP users (an increase in unsafe sexual practices due to the knowledge that PrEP is protective against HIV), which may lead to an increase in sexually transmitted infections (STIs), exacerbating the secular trend of rising STI rates in many countries.

Since the most recent WHO recommendation, a number of new trials in diverse populations have been conducted. We therefore conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to retrieve the most up-to-date evidence on the effectiveness and safety of oral PrEP compared with placebo, no treatment or alternative oral PrEP medication/dosing schedule in all populations, with a particular emphasis on adherence and risk compensation. This review aimed to inform the decision of the Irish government to implement a PrEP programme and to assist in the development of national clinical practice guidelines on PrEP for HIV prevention.

Methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted, adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.8 The quality of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework.9 This framework is commonly used internationally to aid decisions by policy-makers and ensures a systematic and transparent approach in the development of clinical practice recommendations. This study was registered with PROSPERO (ID: CRD42017065937) and followed an agreed protocol (online supplemental material 1).

bmjopen-2020-048478supp001.pdf (266.8KB, pdf)

Search strategy and selection criteria

Electronic searches were conducted in MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, CRD DARE Database, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and Eurosurveillance reports. Search terms that related to ‘HIV’ were combined with search terms that related to ‘PrEP’ or ‘tenofovir’, and filters for study design (RCTs) were applied (the full search strategy for PubMed is provided in online supplemental material 2). Databases were searched on 5 July 2020. No restrictions were placed based on the location of the intervention or the date of publication. No language restrictions were used; articles in languages other than English were translated where necessary. Table 1 outlines the inclusion criteria for study selection. Animal studies, studies that did not report primary outcome data (HIV incidence) and abstracts from conference proceedings were excluded.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for studies

| Population | Populations at substantial risk of HIV, including men who have sex with men, serodiscordant heterosexual couples, heterosexuals and people who inject drugs |

| Intervention | Oral tenofovir-containing PrEP |

| Comparator | Placebo, no treatment or alternative oral PrEP medication/dosing schedule |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome: relative risk of HIV infection Secondary outcomes:

|

| Studies | RCTs |

PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RCT, randomised controlled trial; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

bmjopen-2020-048478supp002.pdf (174.9KB, pdf)

It was decided a priori that all analyses of effectiveness would be stratified by population. The four populations were MSM, serodiscordant heterosexual couples (individuals whose partners are HIV positive and not virally suppressed on antiretroviral medications), heterosexuals and people who inject drugs (PWIDs).

Data collection

Results of the database search were exported to Endnote V.X7. Full-text articles were obtained for all citations identified as potentially eligible. Two reviewers (EOM and LM) independently screened these according to the prespecified inclusion criteria. Two reviewers (EOM and LM) independently performed data extraction and assessed the risk of bias according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool.10 An overall assessment of the quality of the evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach that included an assessment of other biases, such as publication bias.9

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome measure was the rate ratio (RR) of HIV infection for each population. The rate of HIV infection represented the number of HIV infections that occurred per person-years of follow-up data, and the RR compares the rate of HIV infection in the PrEP group with control. The rate of HIV infection (per person-years) was favoured over risk of HIV infection as rate incorporates both the number of participants and the duration of follow-up, allowing for comparisons across studies that may vary significantly in terms of study duration. The absolute rate difference (RD) of HIV infection was also estimated for each population; in this case, the RD represented the actual difference in the observed rate of HIV between PrEP and control groups per person-year of follow-up data. Meta-analyses of RRs and RDs were performed in Review Manager V.5.3 using Mantel-Haenszel random effects models.

A modified intention-to-treat analysis was employed (and not per-protocol analysis); therefore, effectiveness was a function of both efficacy of the drug itself and adherence. A modified intention-to-treat analysis was selected instead of a standard intention-to-treat analysis to account for unrecognised HIV infection at enrolment. In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, all patients who were HIV negative at enrolment in the study were included in the analyses, and individuals with an unrecognised HIV infection prior to enrolment were excluded.

Clinical heterogeneity was assessed by the reviewers based on the description of the interventions and comparators in the RCTs. Statistical heterogeneity was examined using the I2 statistic (I2 values above 75% represented considerable heterogeneity, per Cochrane Handbook V.6.2, 2021, chapter 10, section 10.10.2). If there was sufficient clinical homogeneity across studies, results were pooled using a random effects Mantel–Haenszel model.

In the estimation of PrEP effectiveness, subgroups of studies were defined by dosing schedule, comparator and adherence. Analyses were stratified by population and adherence. Adherence was dichotomised for subgroup analyses: if the proportion of participants who were adherent was ≥80%, the study was considered ‘high adherence’ and <80% was considered ‘low adherence’. Commonly used measures of adherence include self-report, pill counts, medication event monitoring systems, structured interviews and plasma drug detection methods. Plasma drug monitoring is considered the gold standard for adherence assessment; plasma drug detection was favoured over self-report/pill count in the determination of adherence as it minimises recall bias. In studies that measured only plasma drug concentration in participants who reported taking the study drug, the proportion of samples with study drug detected was multiplied by the self-reported adherence rate. In studies that measured adherence in a number of ways without undertaking plasma drug monitoring, taking a conservative approach, the lowest estimate of adherence was used for subgroup analysis.

To investigate the relationship between efficacy and adherence, a metaregression analysis was conducted (metaregression was considered the appropriate model as it accounts for trial size in analyses). In this analysis, adherence was a continuous variable, and only studies that confirmed adherence through plasma drug monitoring were included. Analyses were conducted in R V.3.6.2, including the meta R package.

In the assessment of the safety of PrEP, the definitions for adverse events and serious adverse events followed the definitions used in the primary studies. Outcome measures were expressed as both RRs of safety events and RDs between groups. In the assessment of behaviour change, the effect of PrEP on condom use, number of sexual partners, recreational drug use and the rate of new STI diagnoses (as a proxy for condomless sex) were assessed. In the assessment of PrEP-related drug mutations, subgroups included patients with unrecognised acute HIV infection at the time of enrolment and patients who seroconverted during the course of the trial. Where there was a lack of data or agreed definitions for these outcomes, a narrative review was performed.

In the case of pooling data for rare events, there can be issues with the inclusion of studies with zero events in one or both arms.11 A common approach where there are zero events in one arm is to apply a continuity correction whereby all cells in the two by two table for a given study have 0.5 added to avoid division by zero. This approach can lead to bias, particularly for small trials or those with imbalanced arms. Trials with zero events in both arms are typically excluded, leading to a loss of information. Approaches are available to include zero event trials with application of a continuity correction. For this study, if trials with zero events in one or both arms were identified, a sensitivity analysis using a random effects Poisson regression11 and beta-binomial12 models was applied to determine whether the results were sensitive to the presence of trials with zero events in one or both arms. The main analysis excluded trials with zero events in both arms, as has been recommended when a treatment effect is considered likely.13

In the assessment of publication bias, funnel plots were used when there were more than 10 studies available for analysis. Standard approaches to funnel plots and tests for small study bias use the log(OR) or log(RR), which are not independent of their estimated SE creating a bias. Those tests also have the limitation that they omit studies that have zero events in both arms. To overcome these issues, the arcsine test for publication bias was used.14

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in this research.

Results

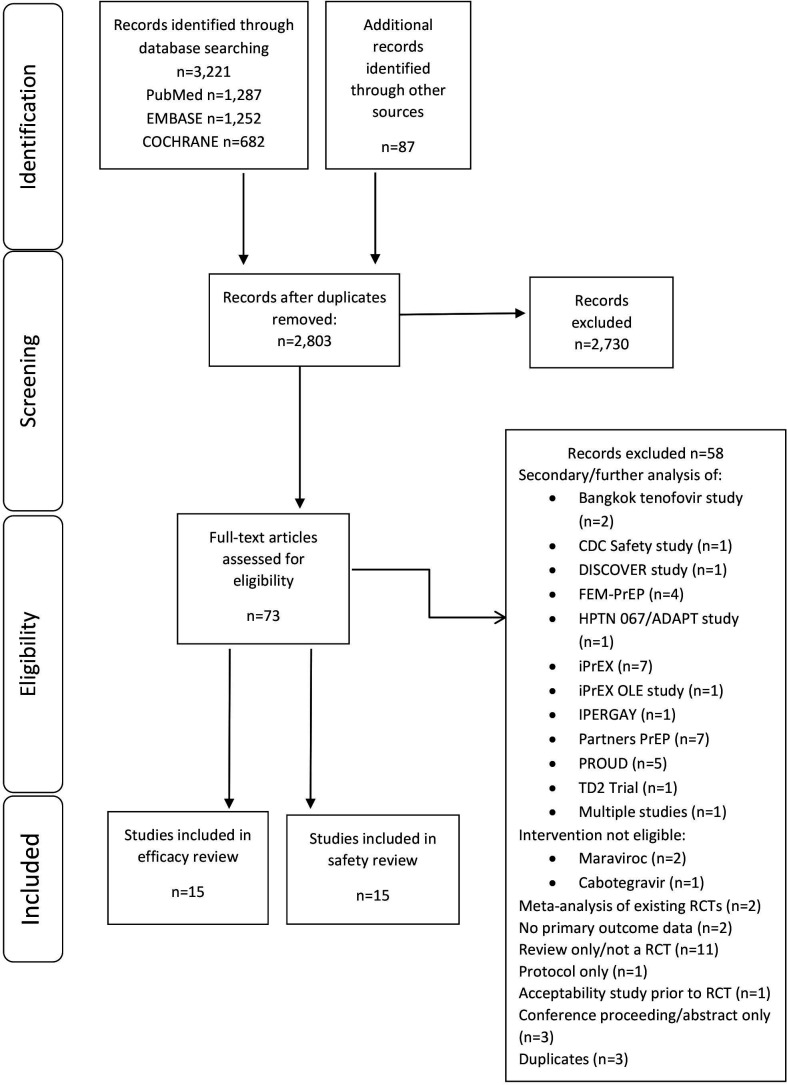

A total of 2803 unique records were retrieved, resulting in 73 studies for full-text review (figure 1 provides the PRISMA diagram of study selection, and the list of excluded studies, along with reasons, is provided in online supplemental material 3.1). Fifteen RCTs met our inclusion criteria and were included in the assessment of effectiveness and safety. Seven RCTs were placebo-controlled trials that evaluated daily oral PrEP.3 7 15–19 Two studies randomised participants to receive either immediate or delayed PrEP.6 20 Three placebo-controlled trials investigated non-daily PrEP, including intermittent and ‘on-demand’ (also known as event-based) PrEP.5 21 22 Two RCTs did not contain a ‘no PrEP’ arm (placebo or no medication): one compared tenofovir with tenofovir/FTC23 and one compared three different PrEP dosing schedules.24 One study contained three arms: PrEP, placebo and ‘no pill’.25 Four distinct patient populations were assessed. Six RCTs enrolled MSM3 5 6 20 21 25; five enrolled heterosexual participants7 16 17 19 24; three enrolled serodiscordant couples18 22 23; and one enrolled PWIDs.15

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram of the study selection. Diagram provides details on the selection process of studies for inclusion. Note that the exclusion of 2703 citations at the ‘screening’ stage did not meet our study inclusion/exclusion criteria based on screening of title/abstract. CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DISCOVER, study by Mayer et al.;28 FEM-PrEP, study by Van Damme et al.;7 HPTN 067/ADAPT, study by Bekker et al;24 IPERGAY, study by Molina et al.;5 iPrEX, study by Grant et al;3 OLE, open label extension; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PROUD, study by McCormack et al.;6 RCT, randomised controlled trial.

bmjopen-2020-048478supp003.pdf (741.2KB, pdf)

Included studies involved 25 051 participants encompassing 38 289 person-years of follow-up data. Of the 15 062 participants that received active drug in the intervention arms of trials, 55% received combination tenofovir/FTC and 45% received single-agent tenofovir. Follow-up periods ranged from 17 weeks to 6.9 years. Four trials were conducted in high-income countries (USA, England, France and Canada); 10 were conducted in low-income or middle-income countries (including 9 trials in sub-Saharan Africa); and one was a multicentre trial conducted across four continents. All studies reported the results of a modified intention-to-treat analysis.

The main characteristics of included studies are provided in table 2.

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Study | Location | Population | Intervention | Comparison | Participants (n) | Follow-up (PYs) | Adherence: high (≥80%) vs low (<80%)* |

| MSM | |||||||

| Hosek et al (Project PrEPare)25 | USA | MSM, median age: 20 years | TDF/FTC | Daily PrEP versus placebo or ‘no pill’ | 58 | 27 | Low: 62% by self-report |

| Grohskopf et al (CDC Safety Study)20 | USA | MSM, age range: 18–60 years | TDF | Immediate or delayed PrEP versus immediate or delayed placebo | 400 | 800 | Low: 77% by pill count |

| Grant et al (iPrEx)3 | Brazil, Ecuador, South Africa, Peru, Thailand and USA | MSM (99%) and transgender women (1%), age range: 18–67 years | TDF/FTC | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 2499 | 3324 | Low: 51% by plasma drug detection |

| McCormack et al (PROUD)6 | UK | MSM, median age: 35 years | TDF/FTC | Immediate PrEP versus delayed PrEP | 544 | 504 | High: 88% (self-report and plasma drug detection†) |

| Molina et al (IPERGAY)5 | Canada and France | MSM, median age: 34.5 years | TDF/FTC | Intermittent (‘on-demand’‡) PrEP versus placebo | 400 | 431 | High: 86% by plasma drug detection |

| Mutua et al (IAVI Kenya Study)21 | Kenya | MSM (93%) and female sex workers (7%), mean age: 26 years | TDF/FTC | Daily or intermittent PrEP versus daily or intermittent placebo | 72 | 24 | High: 83% by MEMS |

| Serodiscordant heterosexual couples (when the HIV-positive partner is not on antiretroviral treatment) | |||||||

| Kibengo et al (IAVI Uganda Study)22 | Uganda | Serodiscordant couples (negative partner: 50% male), mean age: 33 years | TDF/FTC | Daily or intermittent PrEP versus daily or intermittent placebo | 72 couples | 24 | High: 98% by MEMS |

| Baeten et al (Partners PrEP Study)18 | Kenya and Uganda | Serodiscordant couples (negative partner: 61%–64% male), age range: 18–45 years | TDF/FTC and TDF only | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 4747 couples | 7830 | High: 82% by plasma drug detection |

| Baeten et al (Partners PrEP Study Continuation)23 | Kenya and Uganda | Serodiscordant couples (negative partner: 62%–64% male), age range: 28–40 years | TDF/FTC and TDF only | TDF/FTC versus TDF | 4410 couples | 8791 | Low: 78.5% by plasma drug detection |

| Heterosexuals | |||||||

| Bekker et al (ADAPT Cape Town)24 | South Africa | Women, median age: 26 years | TDF/FTC | Daily, time and event-driven PrEP | 191 | 99 | Low: 53%–75% by MEMS |

| Marrazzo et al (VOICE)19 | South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe | Women, median age: 24 years | 5 arms: TDF/FTC, TDF only, 1% TDF vaginal gel, oral placebo and placebo vaginal gel | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 4969 | 5509 | Low: 29% by plasma drug detection |

| Peterson et al 200717 | Nigeria, Cameroon and Ghana | Women, age range: 18–34 years | TDF | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 936 | 428 | Low: 69% by pill count |

| Thigpen et al (TENOFOVIR2)16 | Botswana | Heterosexual men (54.2%) and women (45.8%), age range: 18–39 years | TDF/FTC | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 1219 | 1563 | High: 84.1% by pill count |

| Van Damme et al (FEM-PrEP)7 | Tanzania, South Africa and Kenya | Women, median age: 24.2 years | TDF/FTC | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 2120 | 1407 | Low: 24% by plasma drug detection |

| PWIDs | |||||||

| Choopanya et al (Bangkok Tenofovir Study)15 | Thailand | PWID (80% male), median age: 31 years | TDF | Daily PrEP versus placebo | 2413 | 9665 | Low: 67% by plasma drug detection |

In all cases, tenofovir dose was 300 mg and FTC dose was 200 mg.

*Adherence refers to the proportion of participants in trials that adhered to the study drug. In most studies, more than one method was used to measure adherence; taking a conservative approach, the trials used the lowest estimate of adherence. In trials that investigated daily and intermittent PrEP, adherence relates to daily PrEP. In studies that measured tenofovir and FTC separately, adherence refers to tenofovir detection.

†PROUD trial: adherence was determined by a combination of self-report and plasma drug detection. Sufficient study drug was prescribed for 88% of the total follow-up time, and the study drug was detected in 100% of participants who reported taking PrEP.

‡On-demand dosing: participants were instructed to take two pills of TDF/FTC or placebo 2–24 hours before sex, followed by a third pill 24 hours later and a fourth pill 48 hours later.

FTC, emtricitabine; MEMS, medication event monitoring system; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PWID, people who inject drugs; PY, person-years; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and emtricitabine fixed-dose combination.

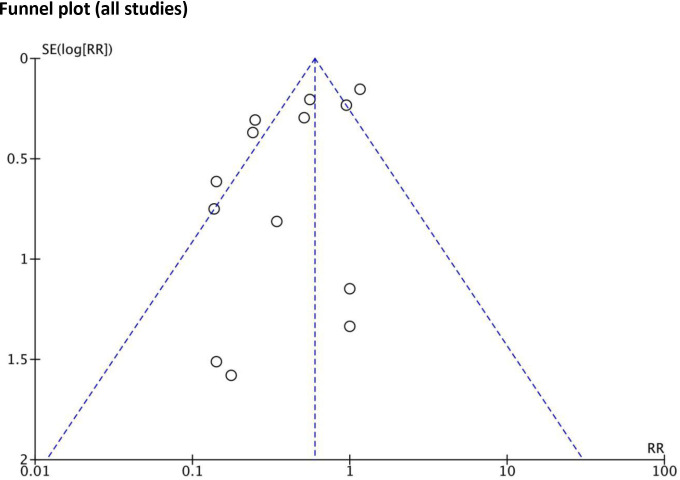

All included individual RCTs were judged to have a low risk of bias by the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (risk of bias graph and summary provided in online supplemental material 3.2, figures S1, S2, respectively). Across studies, while publication bias may have been present in earlier, industry-funded studies (with fewer participants), this form of bias was considered less likely in the more recent, larger, publicly funded studies. To investigate publication bias, the arcsine test for funnel plot asymmetry was applied to all 13 trials (as there were too few trials in individual population groups). The p values for the equivalent of the Begg, Egger and Thompson tests were 0.58, 0.14 and 0.13, respectively. As such, it was determined that there was no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for publication bias. The funnel plot of all studies (n=13) is presented. There is no evidence of significant small study bias. RR, rate ratio.

Effectiveness

The following sections present the effectiveness of PrEP to prevent HIV acquisition by study population and stratified by adherence, where appropriate. Tables 3 and 4 present the GRADE ‘summary of findings’ assessment of the effectiveness and safety of PrEP (and a forest plot of all studies is provided in online supplemental material 3.3, figure S3).

Table 3.

GRADE summary of findings: PrEP effectiveness

| Summary of findings table: Effectiveness of PrEP | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV prevention in participants at substantial risk Intervention: PrEP Comparison: no PrEP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect, expressed as RRs (95% CI) |

Person-years of follow-up (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Rate with no PrEP | Rate with PrEP | |||||

| HIV infection: MSM (all clinical trials) | 40 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (4 to 24) |

RR 0.25 (0.10 to 0.61) |

5103 (6 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High†‡ |

PrEP is effective in preventing HIV acquisition in MSM with a rate reduction of 75%. |

| HIV infection: MSM, trials with high (≥80%) adherence | 66 per 1000 | 9 per 1000 (4 to 23) |

RR 0.14 (0.06 to 0.35) |

960 (3 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

PrEP is highly effective in preventing HIV acquisition in MSM in trials with high adherence (over 80%) with a rate reduction of 86%. |

| HIV infection: MSM, trials with low (<80%) adherence§ | 32 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (12 to 26) |

RR 0.55 (0.37 to 0.81) |

4143 (3 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

PrEP is effective in preventing HIV acquisition in MSM in trials with low adherence (under 80%) with a rate reduction of 45%. |

| HIV infection: serodiscordant couples,¶ all clinical trials: two studies with high (≥80%) adherence | 20 per 1000 | 5 per 1000 (3 to 9) |

RR 0.25 (0.14 to 0.46) |

5237 (2 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

PrEP is effective in preventing HIV acquisition in serodiscordant couples with a rate reduction of 75%. |

| HIV infection: heterosexual transmission, all clinical trials | 41 per 1000 | 32 per 1000 (19 to 53) |

RR 0.77 (0.46 to 1.29) |

6821 (4 RCTs) |

⨁⨁◯◯ Low†** |

PrEP is not effective in preventing heterosexual HIV transmission (all trials). |

| HIV infection: heterosexual transmission, trials with high (≥80%) adherence | 31 per 1000 | 12 per 1000 (6 to 26) |

RR 0.39 (0.18 to 0.83) |

1524 (1 RCT) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

PrEP is effective in preventing heterosexual HIV transmission in heterosexuals in one trial with high (over 80%) adherence. This trial enrolled men and women; note that efficacy was only reported for men. |

| HIV infection: heterosexual transmission, trials with low (<80%) adherence | 45 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (34 to 64) |

RR 1.03 (0.75 to 1.43) |

5297 (3 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate** |

PrEP is not effective in preventing heterosexual HIV transmission in trials with low adherence. Note that all three trials enrolled heterosexual women. |

| HIV infection: PWID, all clinical trials: one study with low (<80%) adherence | 7 per 1000 | 3 per 1000 (2 to 6) |

RR 0.51 (0.29 to 0.92) |

9666 (1 RCT) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate†† |

PrEP is effective in preventing HIV transmission in PWID with a rate reduction of 49%. |

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence.

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

*The rate in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed rate in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

†Downgraded one level for heterogeneity.

‡Upgraded one level for large effect (RR <0.5).

§Note that under alternative methods to account for zero events in one or both arms (beta-binomial), there is greater imprecision and the upper confidence bound crosses the line of no effect.

¶In studies that enrolled serodiscordant couples, the HIV-positive individual was not on antiretroviral therapy. All studies relate to serodiscordant heterosexual couples.

**Downgraded one level for imprecision.

††Downgraded one level for indirectness.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; PWID, people who inject drugs; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, rate ratio.

Table 4.

GRADE summary of findings: safety of PrEP

| Summary of findings table: Safety of PrEP | ||||||

| Patient or population: HIV prevention in participants at substantial risk. Intervention: PrEP. Comparison: no PrEP | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) |

Person-years of follow-up (studies) |

Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Comments | |

| Rate with no PrEP | Rate with PrEP | |||||

| Safety outcome: any adverse event | 776 per 1000 | 784 per 1000 (768 to 799) |

RR 1.01 (0.99 to 1.03) |

17 358 (10 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

Adverse events do not occur more commonly in patients taking PrEP compared with placebo. Adverse events were common in trials (78% of patients reporting 'any' event). |

| Safety outcome: serious adverse events | 81 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (60 to 91) |

RR 0.91 (0.74 to 1.13) |

17 778 (12 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁⨁ High |

Serious adverse events do not occur more commonly in patients taking PrEP compared with placebo. Serious adverse events occurred in 7% of patients in trials but most were not drug related. |

| Safety outcome: deaths | 13 per 1000 | 10 per 1000 (8 to 15) |

RR 0.83 (0.60 to 1.15) |

12 720 (11 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate† |

Deaths did not occur more commonly in people taking PrEP compared with placebo in trials. No deaths were related to PrEP. |

| Safety outcome: drug resistance mutations in patients with acute HIV at enrolment | 53 per 1000 | 186 per 1000 (62 to 556) |

RR 3.53 (1.18 to 10.56) |

44 (5 RCTs) |

⨁⨁⨁◯ Moderate† |

Patients randomised to receive PrEP who had acute HIV at enrolment were at increased risk of developing resistance mutations to the study drug. Most conferred resistance to emtricitabine. |

Note that only a minority of studies tested for viral drug resistance mutations.

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence.

High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

*The rate in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed rate in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

†Imprecision was detected due to few observations.

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RR, rate ratio.

Effectiveness in MSM

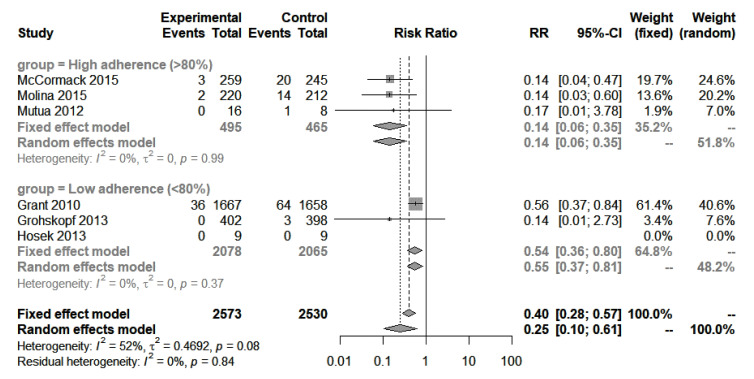

Six studies enrolled MSM.3 5 6 20 21 25 A meta-analysis of all studies resulted in an RR of 0.25 (95% CI 0.1 to 0.61), indicating a 75% reduction in the rate of HIV acquisition (figure 3). The estimated absolute RD was −0.03 (95% CI −0.01 to −0.05), indicating PrEP users had a 3% lower rate of HIV acquisition per person-year of follow-up.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis: HIV acquisition in MSM, all studies. Forest plot of the meta-analysis of HIV incidence in all MSM trials, PrEP versus placebo or no drug. Subgroups include high (≥80%) adherence and low (<80%) adherence. ‘Events’ refers to new HIV infections and ‘total’ refers to total person-years at risk during the study period. MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RR, rate ratio.

When stratified by adherence (≥80% vs <80%), heterogeneity was eliminated (I2 reduced from 52% to 0%). PrEP was most effective in studies with high adherence (≥80%), as expected, where the rate of HIV acquisition was reduced by 86% (RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.35; RD −0.06, 95% CI −0.04 to −0.09; I2=0%, n=3 studies).5 6 21 Of the three studies with high adherence, one study was small and reported non-significant findings due to few events (Mutua et al21). Of the remaining two studies, one study investigated daily PrEP use (McCormack et al, PROUD trial)6 and the other investigated on-demand PrEP (Molina et al, IPERGAY trial).5 Both studies reported identical efficacy (PROUD: RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.47; IPERGAY: RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.6).

When adherence was under 80%, acquisition rate was reduced by 45% (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.81; RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.00 to −0.02; I2=0%, n=3 studies).3 20 23 25

Effectiveness in serodiscordant heterosexual couples

In all three studies that enrolled serodiscordant heterosexual couples, the HIV-infected partner was not on antiretroviral therapy (studies were conducted in Kenya and Uganda; HIV-infected participants did not meet the criteria for antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation at the time of enrolment).18 22 23 Details on the CD4 count (a type of cell that HIV infects) or viral load of the HIV-infected partners were not reported.

Two studies investigated the effect of daily oral PrEP compared with placebo.18 22 A total of 4819 couples were enrolled, and the seronegative individual was male in the majority (>60%) of cases. One trial enrolled few participants (n=24 in the daily PrEP arm), and the duration of the trial was very short (4 months); this study did not contribute to analyses as no seroconversions were reported in either arm of the trial.22 The trial by Baeten et al18 consisted of three arms: tenofovir/FTC (n=1568 participants), tenofovir alone (n=1572 participants) and placebo (n=1568 participants). Tenofovir/FTC resulted in a 75% rate reduction (RR 0.25, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.46; RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.02), and tenofovir alone resulted in a 67% rate reduction (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19 to 0.56; RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.02). A continuation of this trial (Baeten et al23) compared tenofovir/FTC with tenofovir alone: there was no significant difference between groups.

Effectiveness in heterosexuals

Of the five studies enrolling heterosexual participants, four were placebo-controlled7 16 17 19 and one compared different drug schedules.24 Four studies enrolled only women,7 17 19 24 and one study enrolled both men and women.16 All studies were conducted in a high-HIV prevalence context (countries in sub-Saharan Africa). A meta-analysis of the four placebo-controlled studies7 16 17 19 did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in HIV acquisition (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.29; I2=66%; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S4). In the only trial with high adherence (Thigpen et al16), a rate reduction of 61% was noted (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.83; RD −0.02, 95% CI −0.01 to −0.04). This was the only trial to enrol both men and women, and when the results were analysed separately by sex, efficacy was noted only in men, with a rate reduction of 80% (RR 0.2, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.91; online supplemental material 3.4). As expected, in a meta-analysis of trials with low adherence, the result was non-significant (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.43, I2=21%; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S5).

A final study compared different PrEP regimens (daily PrEP, ‘time-driven’ PrEP and ‘event-driven’ PrEP).24 Fewer infections occurred in the daily PrEP arm; however, there were no significant differences in HIV acquisition comparing either event or time-driven PrEP with daily PrEP.

Effectiveness in PWID

Only one study enrolled PWID.15 Daily oral tenofovir was found to be effective, with a 49% reduction in HIV acquisition (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.92; RD −0.00, 95% CI −0.00 to −0.01). In this study, HIV transmission may have occurred sexually or parenterally.

Sensitivity analysis

A sensitivity analysis was applied to determine whether the use of continuity correction and the omission of studies with zero events in both arms impacted on the results. First, a meta-analysis of all trials was conducted. Both the Poisson regression and beta-binomial models produced results similar to those of the standard approach (table 5), providing reassurance that the impact of excluding smaller studies with zero events was small. Second, a meta-analysis of studies in the MSM group was undertaken, stratified by adherence, as these analyses included three studies with zero events in one or both arms (table 5). Only the beta-binomial model converged on a stable result. The RR and 95% CI were very similar to the main analysis for the high-adherence group. However, there was greater imprecision in the low-adherence group, and the wider confidence bounds included the possibility of no effect.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis

| Group | Method of analysis | Rate ratio | 95% CI |

| All studies (13 studies) | Standard approach (Mantel-Haenszel) | 0.41 | 0.26 to 0.67 |

| Poisson regression | 0.375 | 0.225 to 0.625 | |

| Beta-binomial | 0.437 | 0.210 to 0.911 | |

| MSM group: high adherence (3 studies) | Standard approach (Mantel-Haenszel) | 0.14 | 0.06 to 0.35 |

| Beta-binomial | 0.134 | 0.063 to 0.284 | |

| MSM group: low adherence (3 studies) | Standard approach (Mantel-Haenszel) | 0.55 | 0.37 to 0.81 |

| Beta-binomial | 0.428 | 0.038 to 4.815 |

MSM, men who have sex with men.

Relationship between efficacy and adherence

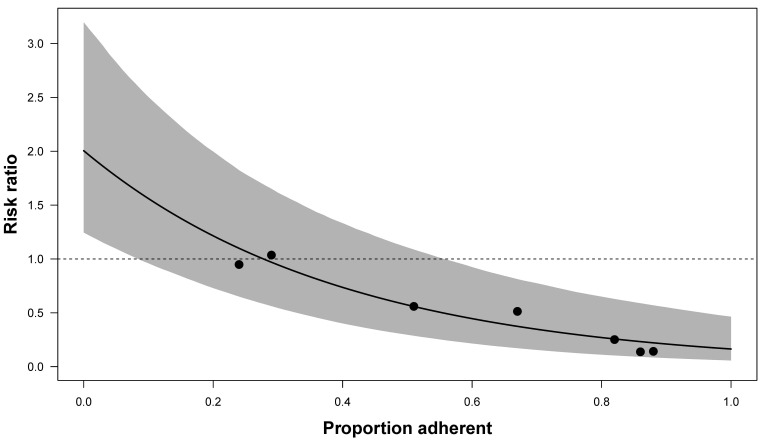

A metaregression analysis was performed to investigate the relationship between efficacy and adherence, accounting for trial size (figure 4; simple regression line provided in online supplemental material 3.3, figure S6). Adherence was measured in a variety of methods across trials (online supplemental material 3.5). Studies that did not confirm adherence through plasma drug detection rates were excluded from metaregression analyses due to biases associated with other methods such as self-report or pill count.

Figure 4.

Fitted metaregression line of the relationship between trial-level PrEP adherence and efficacy. Only trials that reported plasma drug concentration from a representative sample contributed to the analysis, represented as circles (Baeten 201218 (Partners PrEP), Choopanya 201315 (Bangkok Tenofovir Study), Grant 20103 (iPrEx), Mazzarro 201519 (VOICE), McCormack 20156 (PROUD), Molina 20155 (IPERGAY) and Van Damme 20127 (FEM-PrEP)). The solid line represents the fitted regression line and the shaded area represents the 95% CI. The X-axis represents the trial-level adherence as a proportion, and the Y-axis represents the efficacy as rate ratios. PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Efficacy (as RRs) and adherence (by proportion with plasma drug detectable) were strongly associated (p<0.001). As the adherent proportion increases from 0.5 to 0.6, the RR decreases by 0.13. Therefore, on average, a 10% decrease in adherence decreases efficacy by 13%.

Safety

Eleven studies reported data on ‘any’ adverse events, including 10 that compared PrEP with placebo3 5 7 15–19 21 22 and 2 that compared tenofovir alone to tenofovir/FTC.19 23 A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials demonstrated no significant difference between groups (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.03; I2=42%; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S7). Comparing tenofovir with tenofovir/FTC, one study noted a small increase in adverse events in the tenofovir/FTC group (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.33; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S8)19 and another failed to show any difference.23

Of note, several studies reported mild decreases in renal function among PrEP users that returned to normal following discontinuation of PrEP use, while a reduction in creatinine clearance (a measure of renal function) was not observed in others.15 18 Where renal function has been affected, PrEP was associated with mild, non-progressive and reversible reductions in creatinine clearance.3 5 6 15 18 Some trials also found slight decreases in bone mineral density.16 19

All 15 studies reported data in relation to the risk of serious adverse events: 12 were placebo-controlled3 5 7 15–22 25; 1 compared PrEP with no PrEP6; 2 compared tenofovir/FTC with tenofovir19 23; and 1 compared different dosage schedules.24 A meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials did not find an increased risk (RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.13; I2=67%; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S9).

In the only trial that compared PrEP with no treatment, an increased rate of serious adverse events was noted in the treatment arm (RR 3.42, 95% CI 1.4 to 8.35).6 However, these adverse events were not considered study drug-related. Two studies compared tenofovir with tenofovir/FTC: one found no significant difference between groups23 and another found an increased rate in the tenofovir/FTC group (RR 2.48, 95% CI 1.42 to 4.33).19 Of note, not all studies defined what constituted adverse events (including serious adverse events).

No study found an increased mortality rate associated with PrEP use, and of the deaths that occurred, none were considered to be drug-related (online supplemental material 3.3, figure S10).

Viral drug resistance mutations

Five placebo-controlled trials provided data on HIV mutations among patients who had acute HIV infection at enrolment (unknown to study investigators).3 15 16 18 19 In total, there were 44 seroconversions at enrolment, 25 who received the study drug and 19 who received placebo. There were nine mutations detected, eight among participants receiving the study drug and one in a patient receiving placebo. The RR for any drug mutation was 3.53 (95% CI 1.18 to 10.56, I2=0%; online supplemental material 3.3, figure S11), which represents a RD of 0.57 (95% CI 0.21 to 0.94).

Of the nine resistance mutations at enrolment, seven were for FTC. The RR for FTC mutation was 3.72 (95% CI 1.23 to 11.23, I2=0%), which represents an RD of 0.6 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.97) in those receiving tenofovir/FTC (online supplemental material 3.3, figure S12).3 16 18 19

Among participants who seroconverted postrandomisation, the development of resistant mutations was uncommon. Of 551 seroconverters, only seven resistance mutations were detected: one tenofovir mutation was noted in a tenofovir-only arm (k65n, a rare tenofovir resistance mutation) and six FTC mutations were noted.

Risk compensation

Changes in sexual behaviour, or risk compensation, was measured in a number of ways, including condom use, number of sexual partners, changes in STI rates and recreational drug use. Due to the differences in how sexual behaviour was reported across trials, including differing definitions and at different time points, a meta-analysis was not possible.

Studies consistently showed no between-group difference in condom use or number of sexual partners. Studies showed either no overall change in condom use throughout the duration of the study (n=4 studies) or an increase in condom use (n=4 studies). Most studies showed no change in the number of sexual partners over time (n=6 studies); four studies showed a slight reduction in the number of sexual partners; and one showed an increase (investigators of this study noted the possibility of partner under-reporting at baseline).21 No study reported an increase in STIs or a between-group difference in STI diagnoses. In the only study to enrol intravenous drug users, a reduction in intravenous drug use, needle sharing and number of sexual partners over the course of the study was noted.15 Online supplemental material 3.6 presents full details of behaviour change and STI rates in individual studies.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This systematic review and meta-analysis of 25 051 individuals encompassing 38 289 person-years of follow-up data confirms that oral tenofovir-containing PrEP is both effective and safe. PrEP is particularly effective in MSM, with a rate reduction of 75% across all trials, rising to 86% in trials with high adherence. Only one trial investigated the effectiveness of on-demand PrEP.5 This trial reported a rate reduction of 86%, identical to the only comparable trial among daily PrEP users6 (both trials enrolled a large sample of MSM and achieved high levels of adherence). PrEP is also effective in serodiscordant couples, and no significant difference exists between single-agent tenofovir and combination tenofovir/FTC.

Questions remain regarding PrEP effectiveness in other populations. One study found that PrEP was effective in PWID.15 However, a limitation of this study is that investigators were not sure if transmission was parenteral or sexual. It is unclear if PrEP is effective in heterosexuals. PrEP was effective in preventing heterosexual HIV transmission in one trial where adherence was high (61% reduction),16 but only in male participants. The remaining three heterosexual trials, all conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, enrolled only women and adherence was noted to be very low.7 17 19

Adherence varied greatly across studies, ranging from 25% to 88% by plasma drug monitoring. As expected, efficacy was found to be strongly associated with adherence (p<0.01). On average, a 10% reduction in adherence reduced efficacy by 13%.

PrEP was found to be safe, and there was no difference in adverse event rates comparing single-agent tenofovir with tenofovir/FTC in combination. Some studies noted a transient elevation of creatinine with resolution on discontinuation of the study drug.3 5 6 15 18 While uncommon, viral drug resistance mutations may occur in the presence of an unrecognised HIV infection at enrolment.

Our findings of high effectiveness in MSM have been confirmed by two open-label extensions26 27 that followed the conclusion of four RCTs included in this review.3 5 20 25 One open-label extension found no seroconversions in participants that took a minimum of four pills per week.26

Ongoing studies

Following the conclusion of this review, an additional search was conducted to identify recently published or ongoing RCTs after the date of our database search. PubMed was searched using the same search strategy up to 9 September 2021. No additional PrEP efficacy trials were identified, although two publications were identified that relate to an ongoing non-inferiority RCT that compared two different types of oral tenofovir-containing PrEP: tenofovir alafenamide plus FTC versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) plus FTC28 29 (all studies in this systematic review relate to TDF). Interim results found that the daily tenofovir alafenamide group showed non‐inferior efficacy to the daily TDF group for HIV prevention, and the number of adverse events for both regimens was low. Tenofovir alafenamide had more favourable effects on bone mineral density and biomarkers of renal safety than TDF,28 but there was more weight gain among participants who had received tenofovir alafenamide (median weight gain 1.7 kg vs 0.5 kg, p<0.0001).29

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review assessed the use of PrEP in all potentially eligible populations and provided a GRADE assessment of important outcomes,9 ensuring a systematic and transparent approach in the development of national clinical practice guidelines for the prevention of HIV. Based on the strength of the evidence, this study was used to develop national clinical guidelines on the management of patients on PrEP30 and informed the decision of the Irish government to implement a publicly funded PrEP programme nationally for MSM and serodiscordant couples at increased risk, and for other populations on a case-by-case basis as determined by the treating HIV specialist.31

Despite the strength of the evidence, however, the present study is subject to a number of limitations. First, there was a lack of data on a number of other high-risk groups, such as transgender women (only one study included transgender women, which made up less than 1% of participants3) and sex workers (one study included sex workers, but disaggregated data were not reported17). Second, adherence was notably poor in most studies that enrolled heterosexual women, limiting conclusions in this group. Additionally, as observational studies were excluded from this review, PrEP effectiveness may be lower in real-world settings in all populations if adherence is suboptimal. Third, while PrEP is considered to have an excellent safety profile, the maximum follow-up period was 6.9 years in this review and, therefore, long-term safety was not assessed.

Fourth, while studies in this review did not detect risk compensation, evidence from placebo-controlled trials is often insufficient to determine its presence. It is not possible to reach conclusions on the impact of PrEP on behaviour when participants do not know if they are taking active PrEP or placebo. However, it is possible to evaluate the impact of the support provided to all participants over time (provision of condoms and counselling on safer sex practices). Studies generally demonstrated no change or an improvement in safer sex practices. In the open-label PROUD study (where participants knew they were taking PrEP), there was no difference between the immediate and deferred PrEP groups in the total number of sexual partners in the 3 months prior to the 1-year questionnaire.6 However, a greater proportion of the immediate group reported receptive anal sex without a condom with 10 or more partners compared with the deferred group. Importantly, there was no difference in the frequency of bacterial STIs between groups, the most reliable proxy for changes in sexual behaviour (as it is not self-reported). Fifth, a number of studies in this review had zero events in one or both arms of the study. Standard meta-analytical approaches typically exclude these trials, resulting in a loss of data. A sensitivity analysis using alternative meta-analytical methods to account for these studies generally found similar findings, with the exception of the estimate of effectiveness in the low-adherence MSM group, which was no longer statistically significant.

Finally, the generalisation of studies to other clinical settings should be done with caution. All trials that enrolled heterosexuals were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, a part of the world with a generalised HIV epidemic and suboptimal antiretroviral coverage. Additionally, the only trial that enrolled PWID was conducted in Bangkok, where needle exchange was unavailable to participants, and investigators could not differentiate sexually from parenterally acquired HIV.

Research in context and implications for practice

HIV infection is of significant public health importance. There were 523 diagnoses of HIV notified in 2018 in Ireland, representing a rate of 11 per 100 000 population, and over half (56%) of all diagnoses were in the MSM group.32 The rate of HIV in Ireland is high compared with other countries in Western Europe, many of which have seen declines in their HIV rates in recent years.1 This highlights the ongoing need for newer, more effective prevention strategies to halt the transmission of HIV.

Our finding of high PrEP effectiveness among MSM concurs with other recent systematic reviews that focused solely on the MSM population.33 34 To our knowledge, this systematic review provides the first GRADE assessment of the totality of evidence across all populations that includes more recent trials with high adherence.5 6 Our GRADE assessment differs significantly from that of Okwundu et al published in 2012.35

Our quantification of the strength of the association between adherence and efficacy through metaregression highlights the clinical importance of medication adherence support and counselling to prospective PrEP users. Additionally, our finding of FTC resistance mutations occurring almost four times more often in those with acute HIV enrolment has implications for PrEP implementation going forward. Assessing if the patient could be in the ‘window period’ (the time between exposure to HIV and the point when HIV testing will give an accurate result) at enrolment is of critical importance to ensure the patient is HIV negative prior to commencing PrEP. This highlights the need for PrEP delivery as part of a monitored programme that incorporates HIV testing and patient counselling on the risk and long-term consequences of resistance if poorly adherent to PrEP.

An additional finding of interest is the lack of significant difference in the effectiveness and safety of single-agent tenofovir compared with combined tenofovir/FTC. This may have implications for clinical practice, as tenofovir may be a suitable alternative for FTC-allergic patients, and in resource-poor settings if cost or procurement of combination tenofovir/FTC is an issue.

Conclusions

In conclusion, high-certainty evidence exists that PrEP is safe and, assuming adequate adherence, effectively prevents HIV in MSM and serodiscordant couples. One study found PrEP to be effective in PWIDs. The uncertainty regarding PrEP effectiveness in heterosexual individuals persists. Clinicians and policy-makers may decide to recommend PrEP to heterosexual individuals on a case-by-case basis, acknowledging adherence-related issues reported in trials. This review emphasises the importance of adherence support to ensure PrEP effectiveness is maintained, as well as the need for frequent HIV testing at enrolment and follow-up to avoid viral drug resistance mutations. Following the conclusion of this study, the Irish government implemented a publicly funded PrEP programme for all individuals at increased risk of HIV acquisition and developed national clinical practice guidelines for the provision of PrEP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the HSE’s Sexual Health and Crisis Pregnancy Programme, the Gay Men’s Health Centre Dublin, HIV Ireland and Act Up Dublin and the Gay Health Network.

Footnotes

Contributors: EOM: concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of paper for important intellectual content and statistical analysis, overall content guarantor. LM: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content. CT: concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of paper for important intellectual content, statistical analysis and supervision. PH: concept and design, critical revision of paper for important intellectual content, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and supervision. CH: concept and design, drafting of the manuscript and supervision. PM: concept and design, drafting of the manuscript and supervision. MR: concept and design, critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, drafting of the manuscript and supervision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study did not require ethics approval as no human participants were involved.

References

- 1.UNAIDS . Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2020 fact sheet, 2020. Available: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet [Accessed 11 Sep 2021].

- 2.WHO . Consolidated guidelines on HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care for key populations, 2014. Available: https://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/keypopulations/en/ [Accessed 22 Jul 2019]. [PubMed]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2010;363:2587–99. 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . WHO expands recommendation on oral preexposure prophylaxis of HIV infection (PreP), 2015. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/197906/WHO_HIV_2015.48_eng.pdf;jsessionid=7B04813AFDE92D7F5EE3D71C8E921BBA?sequence=1 [Accessed 22 Jul 2019].

- 5.Molina J-M, Capitant C, Spire B, et al. On-demand preexposure prophylaxis in men at high risk for HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2237–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1506273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomised trial. Lancet 2016;387:53–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00056-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:411–22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009;339:b2700. 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.GRADE . The grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (short grade) Working group. Available: http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/

- 10.Cochrane . The Cochrane risk of bias tool. Cochrane Handbook: chapter 8. Available: https://handbook-5-1.cochrane.org/chapter_8/8_assessing_risk_of_bias_in_included_studies.htm

- 11.Beisemann M, Doebler P, Holling H. Comparison of random-effects meta-analysis models for the relative risk in the case of rare events: a simulation study. Biom J 2020;62:1597–630. 10.1002/bimj.201900379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Hong C, Ning Y, et al. Meta-analysis of studies with bivariate binary outcomes: a marginal beta-binomial model approach. Stat Med 2016;35:21–40. 10.1002/sim.6620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng J, Pullenayegum E, Marshall JK, et al. Impact of including or excluding both-armed zero-event studies on using standard meta-analysis methods for rare event outcome: a simulation study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010983. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter J. Arcsine test for publication bias in meta-analyses with binary outcomes. Stat Med 2008;27:746–63. 10.1002/sim.2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok tenofovir study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:2083–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367:423–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterson L, Taylor D, Roddy R, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV infection in women: a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Clin Trials 2007;2:e27. 10.1371/journal.pctr.0020027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2015;372:509–18. 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grohskopf LA, Chillag KL, Gvetadze R, et al. Randomized trial of clinical safety of daily oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;64:79–86. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31828ece33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mutua G, Sanders E, Mugo P, et al. Safety and adherence to intermittent pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV-1 in African men who have sex with men and female sex workers. PLoS One 2012;7:e33103. 10.1371/journal.pone.0033103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kibengo FM, Ruzagira E, Katende D, et al. Safety, adherence and acceptability of intermittent tenofovir/emtricitabine as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among HIV-uninfected Ugandan volunteers living in HIV-serodiscordant relationships: a randomized, clinical trial. PLoS One 2013;8:e74314. 10.1371/journal.pone.0074314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Mugo NR, et al. Single-agent tenofovir versus combination emtricitabine plus tenofovir for pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 acquisition: an update of data from a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:1055–64. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70937-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bekker L-G, Roux S, Sebastien E, et al. Daily and non-daily pre-exposure prophylaxis in African women (HPTN 067/ADAPT Cape town trial): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet HIV 2018;5:e68–78. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30156-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosek SG, Siberry G, Bell M, et al. The acceptability and feasibility of an HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trial with young men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;62:447–56. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182801081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2014;14:820–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70847-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Molina J-M, Charreau I, Spire B, et al. Efficacy, safety, and effect on sexual behaviour of on-demand pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV in men who have sex with men: an observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e402–10. 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30089-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayer KH, Molina J-M, Thompson MA, et al. Emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (DISCOVER): primary results from a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2020;396:239–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31065-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ogbuagu O, Ruane PJ, Podzamczer D, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of emtricitabine and tenofovir alafenamide vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for HIV-1 pre-exposure prophylaxis: week 96 results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet HIV 2021;8:e397–407. 10.1016/S2352-3018(21)00071-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Service Executive (HSE) . Clinical management guidance for individuals taking HIV PrEP within the context of a combination HIV (and STI) prevention approach in Ireland. PrEP clinical management guidance. version 1.1. October 2019, 2019. Available: https://www.sexualwellbeing.ie/for-professionals/prep-information-for-service-providers/guidelines-for-the-management-of-prep-in-ireland.pdf [Accessed 11 Sep 2021].

- 31.Department of Health . Taoiseach and ministers for health announce HIV PreP programme: press release. published on 10 October 2019, 2019. Available: https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/taoiseach-and-ministers-for-health-announce-hiv-prep-programme/ [Accessed 11 Sep 2021].

- 32.Health Protection Surveillance Centre (HPSC) . HIV in Ireland, 2018. Annual epidemiological report, 2019. Available: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/hivandaids/hivdataandreports/HIV_2018_finalrev.pdf [Accessed 11 Sep 2021].

- 33.Huang X, Hou J, Song A, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral TDF-Based pre-exposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:799. 10.3389/fphar.2018.00799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeborn K, Portillo CJ. Does pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men change risk behaviour? A systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2018;27:3254–65. 10.1111/jocn.13990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okwundu CI, Uthman OA, Okoromah CAN. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis (PreP) for preventing HIV in highrisk individuals. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012;7. 10.1002/14651858.CD007189.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-048478supp001.pdf (266.8KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-048478supp002.pdf (174.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-048478supp003.pdf (741.2KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.