Abstract

Brain size and IQ are positively correlated. However, multiple meta-analyses have led to considerable differences in summary effect estimations, thus failing to provide a plausible effect estimate. Here we aim at resolving this issue by providing the largest meta-analysis and systematic review so far of the brain volume and IQ association (86 studies; 454 effect sizes from k = 194 independent samples; N = 26 000+) in three cognitive ability domains (full-scale, verbal, performance IQ). By means of competing meta-analytical approaches as well as combinatorial and specification curve analyses, we show that most reasonable estimates for the brain size and IQ link yield r-values in the mid-0.20s, with the most extreme specifications yielding rs of 0.10 and 0.37. Summary effects appeared to be somewhat inflated due to selective reporting, and cross-temporally decreasing effect sizes indicated a confounding decline effect, with three quarters of the summary effect estimations according to any reasonable specification not exceeding r = 0.26, thus contrasting effect sizes were observed in some prior related, but individual, meta-analytical specifications. Brain size and IQ associations yielded r = 0.24, with the strongest effects observed for more g-loaded tests and in healthy samples that generalize across participant sex and age bands.

Keywords: in vivo brain volume, intelligence, meta-analysis, specification curve analysis, multiverse analysis, systematic review

1. Introduction

Associations between brain volume and intelligence have attracted the interest of the scientific community at least since the early 1800s [1]. This potential association is important for our understanding of (human) intelligence because brain volume is considered to be among the best-replicated correlates of psychometric g (i.e. general cognitive ability; [2]). In this vein, larger brains have been assumed to accommodate more neurons and glial cells which in turn may allow for more complex and quicker information processing. Other researchers have argued that larger brains provide surplus brain tissue that serves as a type of brain reserve, which may protect against a deterioration of cognitive abilities due to ageing- or fitness-related factors (for an overview, see [3]). However, to determine the potential relevance of these mechanisms, it is important to obtain a plausible estimate of the brain volume and IQ association.

Early empirical studies had to rely on proxies for intelligence (e.g. educational achievement) and brain size measures (such as head height, width, circumference or composites of it; e.g. [4]), which introduced considerable statistical noise in the data, thus leading to imprecise estimates of associations. Even with the advent of the first psychometric tests in the early 1900s, the issue of reliable brain volume measurement pertained, thus failing to alleviate validity problems of the observed associations.

It was only the development of neuroimaging methods, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), that allowed reliable assessments of in vivo brain volumes and consequently their link with intelligence. While the direction of the seemingly positive brain size and intelligence link was frequently reproduced, the observed strength varied considerably. The first available report of MRI-assessed brain volume and IQ correlations in healthy men suggested that this association explained an impressive 25% of variance (r = 0.51; [5]), thus representing a large effect according to the well-established effect size classification of Cohen [6]. However, subsequent replications appeared to yield predominantly effects in the small-to-moderate range.

Several narrative reviews have been published that aimed at clarifying the brain-volume and IQ link [7–12]. Although all of them concluded that there is overwhelming evidence for a positive relationship, the strength and consequently meaning of the effect remained unclear. However, this is unsurprising because narrative reviews (i) lack formalized procedures that would allow systematic syntheses of effect sizes or influences of potential moderators and (ii) are vulnerable to various forms of bias (e.g. [13], pp. 301–302).

Systematic numerical effect syntheses by means of meta-analytical approaches are often considered to represent a means to provide definite conclusions about a given research question (i.e. assuming that they have been adequately performed) because they can address both moderator effects and estimate potentially confounding dissemination biases. However, meta-analytic researchers that investigate an identical research question may arrive at surprisingly different conclusions.

It has been demonstrated that design and analytical choices as well as researcher degrees of freedom (decisions that are being made that affect e.g. the specification of inclusion criteria or the selected statistical approach) may lead to substantially varying results from meta-analyses although they are based on similar databases and examine identical research questions (see the multiverse and specification-curve approach to meta-analysis introduced by [14], adopting analogous approaches for primary data analysis, i.e. multiverse analysis, by [15], and specification-curve-analysis, by [16,17]). Typically, there are a variety of reasonable choices that need to be made in regard to any type of study (for an overview, see [18]) which different researchers may (dis)agree about. For meta-analyses in this context, it matters most which studies are included and how they are analysed [14].

Researchers typically have conceptual or methodological reasons to prefer certain specifications over others. However, other researchers may apply different but equally reasonable selection criteria and analysis approaches which necessarily will lead to different summary effect estimations. One prominent example of the effects that such differing methodological choices can have is the widely received but heavily criticized paper that seemingly showed larger death-tolls of hurricanes with female as opposed to those with male names [19] in the prestigious journal PNAS. Although the methodological choices of this study had been well-justified, they represented an extreme specification which represented a single possibility out of a total of 1728 reasonable specifications (i.e. based on a number of published opinions about how these data should have been analyzed) to analyze these data (i.e. under the assumption that all possible meaningful kinds of data to analyze and how to do it had been identified in this study), only 37 of which (i.e. 2.1%) would have led to significantly deadlier hurricanes with female names [16,17].

Such observations have led researchers to argue that data analyses in general and research syntheses in particular should not only rely on a single reasonable specification which may represent only one of many justifiable approaches to treat and analyze data. Providing a distribution of these reasonable approaches allows a multi-faceted evaluation of potential moderating variables in terms of how they affect an effect size in terms of accuracy and strength.

Naturally, researchers may be unaware of all potentially reasonable ways to analyze their data (i.e. both in terms of which data to analyze and how to do so) because they may be unaware about influential factors such as moderating variables. By means of a brute-force approach, all possible (but not necessarily reasonable) ways to calculate meta-analytical summary effects can inform a researcher about potentially meaningful specifications that she may have missed. This means that clustering of summary effects of certain data subsets within the framework of a combinatorial meta-analysis may allow an identification of previously unobserved moderators ([20]; for discussion and an application, [14]).

Moreover, the time-point a certain meta-analysis is performed at can affect its outcomes because of the so-called decline effect (i.e. effect sizes of early studies investigating a given research question are more often than not inflated, thus leading to systematic decreases of effect strengths over time; [21,22]).

So far three meta-analyses have been published about the association between brain size and IQ. They are an illustrative example of the influences on meta-analytical results in terms of which studies have been included as well as when and how a meta-analysis was performed. The first formal meta-analysis about in vivo brain size and IQ associations was published in 2005 [23], yielding evidence for a moderate effect of r = 0.33 (i.e. explaining about 11% of variance; k = 33 independent samples, N = 1530).

About a decade later, this account was updated in the wake of another meta-analysis [24] which included an extension of the search strategy to further literature databases and the revision of the inclusion criteria (i.e. extending the inclusion from associations of only healthy to patient-based samples as well). This investigation yielded a considerably lower summary effect, indicating a small-to-moderate association between brain volume and IQ of r = 0.24 (i.e. explaining about 6% of variance; k = 120 independent samples, N = 6778). Moreover, an application of several dissemination bias assessment methods indicated that this summary effect was likely an inflated estimate due to confounding dissemination bias.

Finally, in another meta-analysis [25], a subset of study effects that had been reported in Pietschnig et al. [24] was synthesized anew. This reanalysis of a selection of studies, focusing merely on a part of the extant research evidence (i.e. about a fifth of the available independent effect sizes, representing a mere fifth of the evidence that was available in 2015), yielded a moderate effect of r = 0.31 (explaining about 10% of variance; k = 32 independent samples, N = 1758), although the authors concluded that the true association with highly g-loaded tests (i.e. g-loadings indicate how close a given test is related with the general factor of intelligence; henceforth referred to as: g-ness) should amount to about r = 0.40 (i.e. corresponding to about 16% of explained variance). Importantly, the analysis of Gignac & Bates [25] represents a comparatively small data subset based on one particular (out of many reasonable) specifications from the data of Pietschnig et al. [24].

These inconsistent results of the meta-analytical effect estimates illustrate how different procedural choices in conducting a meta-analysis are. In fact, the inconsistencies between results of these very three meta-analyses have recently been highlighted as a textbook example of specification-dependent outcomes [14]. The considerable differences of the observed summary effects have obviously meaningful implications for the meaning of the brain volume and IQ link. For instance, when assuming 16% of explained variance of the brain volume and IQ association (i.e. corresponding to the interpretation of [25]), this would mean that 2.4 IQ points of this difference are merely due to their difference in brain size, when observing two individuals with a 10 IQ point difference. But when assuming 6% of explained variance (i.e. corresponding to the estimate of [24]), only 0.9 IQ points are explained by this correlation.

Obviously, such inconsistencies in effect estimations are undesirable. Although brain volume and IQ have consistently been shown to be positively linked in prior research syntheses, the strength and therefore meaningfulness of this link remains unresolved.

In the present case, these differing estimates may be predominantly attributed to two components. On the one hand, a larger estimate of the first published meta-analysis [23] compared to subsequent updates could be attributed to the decline effect, because published primary study effects and consequently meta-analytical summary effects tend to decrease over time [22]. However, a decline effect can be ruled out as the sole cause for these differences because the most recent meta-analysis about this topic [25] yielded a larger effect than the previous estimate. On the other hand, these inconsistencies may be attributable to the different (reasonable) choices that researchers make when conceptualizing their study (or, in certain cases, analysing their data).

In these past three meta-analyses, several differences in terms of such choices can be identified. For instance, the inclusion criteria differed considerably in terms of sample characteristics (healthy versus patients; children/adolescents versus adults). Similarly, the analyses differed in terms of their methodological approaches. While two meta-analyses [23,25] used the so-called psychometric approach as developed by Hunter & Schmidt (e.g. [26]), the third one used the approach as introduced by Hedges & Olkin [27]. These two approaches most notably differ in terms of their underlying philosophy. While the former focuses on potential summary effect underestimations due to suboptimal sampling and measurement inaccuracies in the primary studies, the latter focuses on effect inflation and confounding bias. Consequently, in the former approach larger summary effects are typically obtained because individual study effects are corrected for artefacts such as range restriction or unreliability prior to the effect synthesis. The latter approach yields smaller summary effects because uncorrected estimates are synthesized.

It is evident that these differences in how to synthesize which primary study data necessarily lead to differing results. However, evidently any individual choice of a certain way to synthesize the available data may be criticized in its own right, even if this choice has been reasonably justified, thus leaving the meaning of contradictory findings of isolated meta-analytical summary estimates unresolved.

Novel methods provide a means to explore the multiverse of different design choices by allowing the assessment of a large number of (reasonable) specifications for the effect size synthesis in any given research question, thus providing a range of plausible estimates instead of an isolated point estimate (see [14]).

In the present preregistered meta-analysis of the associations between in vivo brain volume and cognitive abilities (intelligence, IQ), we aimed at resolving the ambiguity of available effect estimates by (i) updating the available meta-analytical data base, (ii) assessing subgroup analysis- and meta-regression-based influences of moderators, (iii) investigating evidence of dissemination bias and (iv) providing a range of effect estimates based on a large number of (reasonable) effect syntheses based on evidence from combinatorial, multiverse analysis, and specification-curve approaches to meta-analysis (see [28], for a similarly designed research synthesis).

2. Methods

The present study was preregistered at the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/r6gnk). Study materials, R-codes, and all data are available at https://osf.io/y6msp/.

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

In order to be included in the present meta-analysis the primary studies were required to fulfil four criteria. First, they had to assess the association between in vivo brain volume and IQ. Second, in vivo brain volume has had to be measured by either MRI or CT. Studies had to provide measurements of the whole brain volume (TBV or ICV). If both were reported, TBV was preferred over ICV. Associations with partial brain area volume were excluded. Third, intelligence had to be measured with psychometric intelligence tests. Fourth, in cases of data dependencies, studies with the most comprehensive account of parameters were preferred. If no such hierarchy could be established, the earliest published account was coded.

Effect sizes were coded separately according to intelligence domain (full-scale, verbal and performance IQ). We used two different analysis methods when multiple subtest correlations within a certain domain were reported. First, in line with standard approaches, we selected those estimates that were judged to be conceptually more closely related to the respective domain (e.g. preferring verbal comprehension over working memory correlations for verbal IQ analyses). Second, we used robust variance estimations (RVE; [29]) to account for data dependencies while retaining the information of all coded information.

In cases where potentially eligible studies did not provide sufficient information to calculate effect sizes, corresponding study authors were contacted. When no response was received, the respective study was excluded (when effect sizes were reported to be non-significant in published papers, but no correlation coefficient was given and no response was received, coefficients were set to zero according to standard meta-analytical procedures; [30], pp. 408–409; in our study 30 out of 454 effect sizes).

2.2. Literature search

To update the so far most comprehensive available data set of IQ and brain size correlations [24], we first searched the online literature databases PubMed, ISI Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar using the string: (brain size AND intelligen*) OR (brain volume AND intelligen*) OR (brain size AND IQ) OR (brain volume AND IQ).

Second, we used a forward citation search of all three published meta-analyses on the subject [23–25]. Third, we conducted an extensive search for unpublished accounts in grey literature databases, search engines and repositories, sources dedicated to theses and dissertations, conference materials and registries for active studies. Finally, reference lists of all identified studies were handsearched for additional potentially eligible studies. Individual search strings and covered databases are available from https://osf.io/7z2u3/. Sample sex ratio, sample type (healthy versus patient samples), test instrument, publication year, mean sample age, participant numbers, effect size estimates and volumetric as well as IQ test standard deviations, number of corrections to the correlation coefficient (e.g. controlling for body height or mass), publication status (i.e. published versus grey literature versus personal communication), sample age (children/adolescents versus adults), brain volume measurement type (TBV or ICV), IQ domain and the assumed g-loadedness of the respectively used intelligence test (g-ness: fair versus good versus excellent; these categories correspond to the three rating criteria of [25], indicating a rank score based on included test number, dimensions and correlation with g; testing time was presently not used as an evaluation criterion; for details refer to [25]) were recorded independently by two researchers (D.G., M.Z.). A coding book containing data sheets and a coding manual explaining all variables and their categories is available at https://osf.io/fr8g7/. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion with a third independent coder (J.P.). All searches were updated on April 14, 2021.

2.3. Synthesis methods

Meta-analytical calculations were performed in R by means of the metafor package [31].

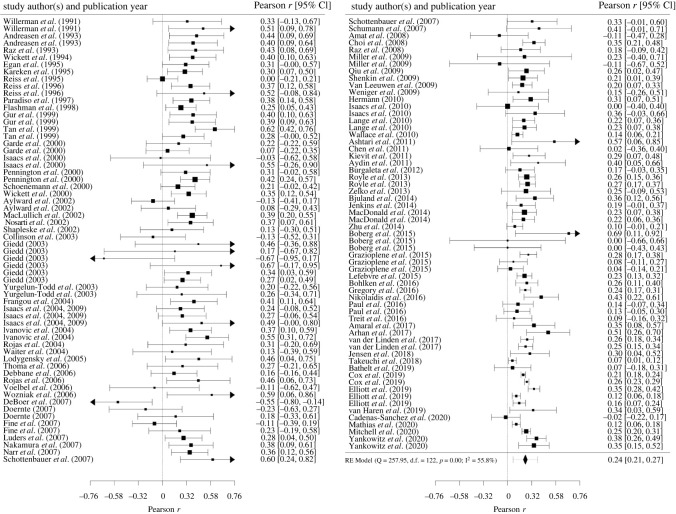

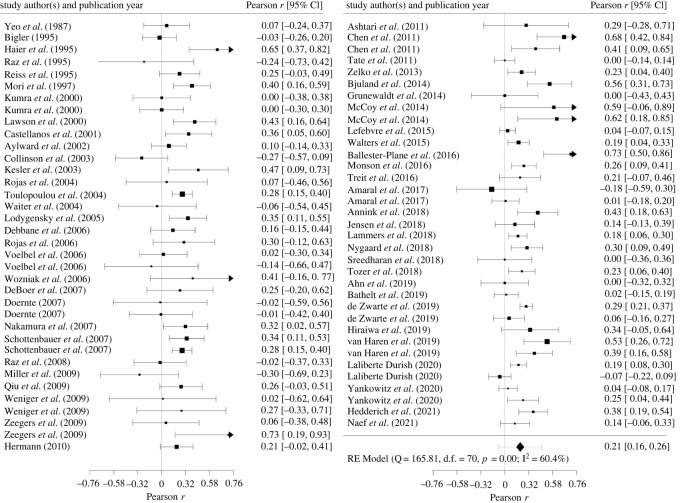

2.3.1. Hedges and Olkin meta-analysis

A random-effects meta-analysis in the tradition of Hedges & Olkin [27] was conducted based on independent effect sizes. Effect syntheses were calculated based on Fisher's z-transformed values to account for the skewed distributions of Pearson rs. For ease of interpretation, results were back-transformed into the r-metric prior to reporting. Some researchers have criticized this procedure because it may introduce a substantial upward bias (see, [26]). Therefore, we conducted a sensitivity analysis with correlations corrected for this negative bias [32].

Effect sizes were weighted according to study precision. Precision of the effect size estimates is illustrated by 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on the Knapp-Hartung adjustment [33,34]. In sensitivity analyses, we conducted leave-one-out analyses to evaluate influences of individual studies on the overall effect size and assessed potential influences of outliers following the approach of Viechtbauer & Cheung [35].

2.3.2. Psychometric meta-analysis

Within the framework of psychometric meta-analyses, researchers aim at accounting for potential measurement inaccuracy and sampling errors. Following the specifications of two previous meta-analyses [23,25], we accounted for direct range restriction only (i.e. using the Case II formula of [36], to correct correlations and the approach of [37], to estimate their standard errors; see, [38]), because (i) reliabilities of MRI and IQ measures are typically high and (ii) reliabilities were infrequently reported [23,25]. Here, we used the n-weighted Hunter and Schmidt estimator (HS) to calculate effect syntheses.

2.3.3. Robust variance estimation

By means of this approach, we were able to include more than one effect size per sample within a particular study and intelligence domain, following current recommendations [39]. Data dependencies within domain-specific analyses (i.e. full-scale versus verbal versus performance IQ) were modelled using robust variance estimation within meta-regressions, thus allowing for including a maximum amount of available information of primary studies (i.e. inclusion of multiple effect sizes from identical participants; this is reasonable because full-scale, verbal and performance IQ results are typically highly intercorrelated), while avoiding inappropriate effect size weighting due to dependent data [40].

We used a correlated-effects model because data dependence was primarily caused by correlations between participants' domain intelligence scores from different (sub)domains. We used τ2 (random-effects maximum likelihood) and ω2 by means of simplistic methods of moments estimators to estimate weights [41]. Fisher's z-transformed correlation coefficients were used for analyses.

2.4. Moderator analyses

2.4.1. Subgroup analyses

Influences of categorical variables were examined in a series of mixed-effects subgroup analyses. We assessed group differences according to sample type (healthy versus clinical), age (children/adolescents versus adults), sex (men versus women) and g-ness. Furthermore, another two supplemental subgroup analyses were performed to (i) further corroborate results of bias analyses (i.e. published in a peer-reviewed journal versus obtained from grey literature or through personal communication) and (ii) assess possible influences of different brain volume measurement types (i.e. total brain volume versus intracranial volume).

2.4.2. Meta-regressions

2.4.2.1. Single regressions

Initially, a series of single regressions of effect sizes on study publication years was calculated for each IQ domain, to assess evidence for a potential decline effect. Differences of associations between intelligence domains were evaluated by means of a RVE-based meta-regression. For each RVE-regression, we ran one model with and one model without intercept to examine differences of coefficients compared to full-scale IQ and regression-based effect estimates for each domain, respectively.

2.4.2.2. Multiple regressions

Subsequently, theory-guided hierarchical multiple precision-weighted mixed-effects meta-regressions were calculated for each domain. In three blocks we included (i) g-ness (only for full-scale IQ analyses; fair/good versus excellent), publication year, publication status; (ii) male ratio, mean sample age and (iii) study goal (i.e. assessment of IQ and brain volume association was the primary study goal versus not), number of included covariates in study. Model fit between blocks was compared by means of likelihood ratio tests. In supplemental analyses, we repeated these calculations only in studies that reported total brain volume (results omitted for brevity).

2.5. Dissemination bias

We used several dissemination bias detection methods to assess potential influences of summary effect-biasing artefacts. The use of multiple detection methods is sensible because different methods have been shown to not be equally sensitive to different bias scenarios and sources [42,43].

Results of bias analyses were based on published data only (excepting direct comparisons) and we focused on healthy samples (i.e. following the specifications of [25], and [23]), because bias may be expected to be stronger in neurotypical samples (i.e. because in non-neurotypical samples, expectations of certain effect strength observations may be lower and reporting of effect sizes therefore less dependent on conforming to preceding observations). Fisher's r-to-z transformed correlation coefficients were used (excepting p-value-based analyses) and analyses were carried out separately for full-scale, verbal and performance IQ.

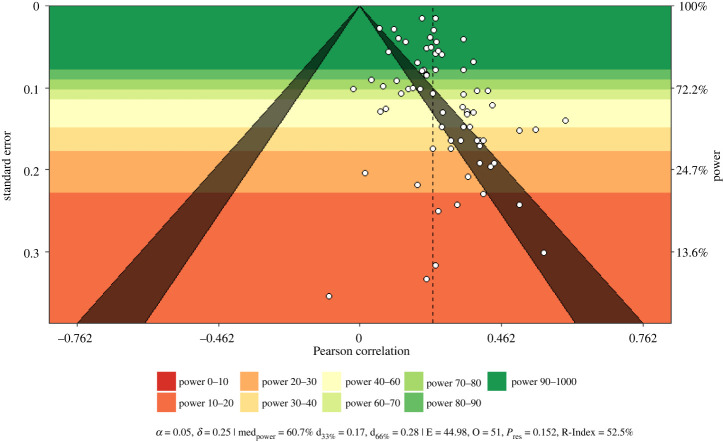

First, we provide power-enhanced funnel plots (i.e. sunset plots, see [44]; using the R package metaviz, [45]) comprising estimates for the median power of all studies, necessary true effect estimates for a median power reduction to 33% or 66%, results of the test of excess significance (TES; observed random-effects summary effects were used for study power calculations; [46]), as well as the R-Index for expected replicability [47].

Second, we used Sterne & Egger's regression approach [48] by regressing effect sizes on the standard normal deviate effect size of the inverse standard error (p-values < 0.10 were considered indicative of bias). Third, the trim-and-fill method [49] was applied to detect potential funnel plot asymmetry. Resulting bias-adjusted estimates were interpreted in terms of a sensitivity analysis rather than a corrected summary effect estimate.

Fourth, we used three novel methods that are based on the distribution of published p-values and provide a means to estimate summary effect sizes and detect evidence for p-hacking and dissemination bias. The methods p-curve [50], p-uniform [51] and p-uniform* [52] are based on the idea that p-values follow a uniform distribution when the true investigated effect of any given research question is zero. In p-curve and p-uniform, only significant p-values are included in the analyses. This makes sense, because significant effects should have an identical publication probability. Observed right-skewness of these distributions are interpreted to be indicative of a true non-zero effect while observed left-skewness indicates confounding effects of p-hacking. Examinations of p-curves allow consequently a formal test of p-hacking by examining the shape of the observed p-value distribution (p-curve) or comparing observed with expected conditional p-values (p-uniform). By minimizing a loss function resulting from inspection of the observed p-value distribution (p-curve) or assessing the value for which the conditional p-value distribution is uniform (p-uniform), summary effects can be estimated.

Effect-size estimations that are based on p-uniform* rely on both significant and non-significant p-values (here, it is assumed that publication probabilities are identical within, but not across, groups). P-uniform has been shown to be more precise than both p-curve and p-uniform in the presence of non-trivial between-studies heterogeneity and allows assessment of the extent of unobserved heterogeneity [52]. P-uniform and p-uniform* were calculated by means of the R package puniform [53] and the R code available from www.p-curve.com/Supplement.

Fifth, we used two selection-model approaches that were either based on the four identical weight functions for p-values, as used in Pietschnig et al. [24]), or on the standard error of the effect sizes [54]. By means of these approaches, the robustness of the summary effect can be assessed when primary study effects are weighted according to them being more or less significant (p-values were weighted according to the approach of [55]) and more or less accurate [54]. We used metasens [56] to conduct the Copas and Shi analysis.

Sixth, we inspected the overlap between two DerSimonian-Laird estimator-based confidence intervals by means of the approach of Henmi & Copas [57]. This method can be seen as a type of sensitivity analysis in which conventionally calculated confidence intervals are compared with those of a hybrid estimation resulting from the use of fixed-effect weights but random-effects heterogeneity estimates. Large discrepancies between effect and confidence interval estimates are considered to be indicative of bias, although there is no consensus about a suitable hard-and-fast decision criterion.

Seventh, we directly assessed potential bias by regressing effect sizes on publication type (published versus unpublished effects). Moreover, we assessed cross-temporal changes in effect size in another meta-regression model, in order to assess the evidence for a potentially confounding decline effect in the data, as evidenced in a predecessor meta-analysis on this topic [24].

Finally, we conducted two cumulative meta-analyses according to (i) sample size and (ii) publication year to further illustrate potential influences of small-study effects and cross-temporal changes.

2.6. Exploring the multiverse

To untangle specific analytical design choices (i.e. reflecting researcher degrees of freedom) from the general pattern of brain size and IQ associations, we explored the multiverse of possible (reasonable) meta-analytic design specifications [14] using the R Code available from https://osf.io/kqgey/.

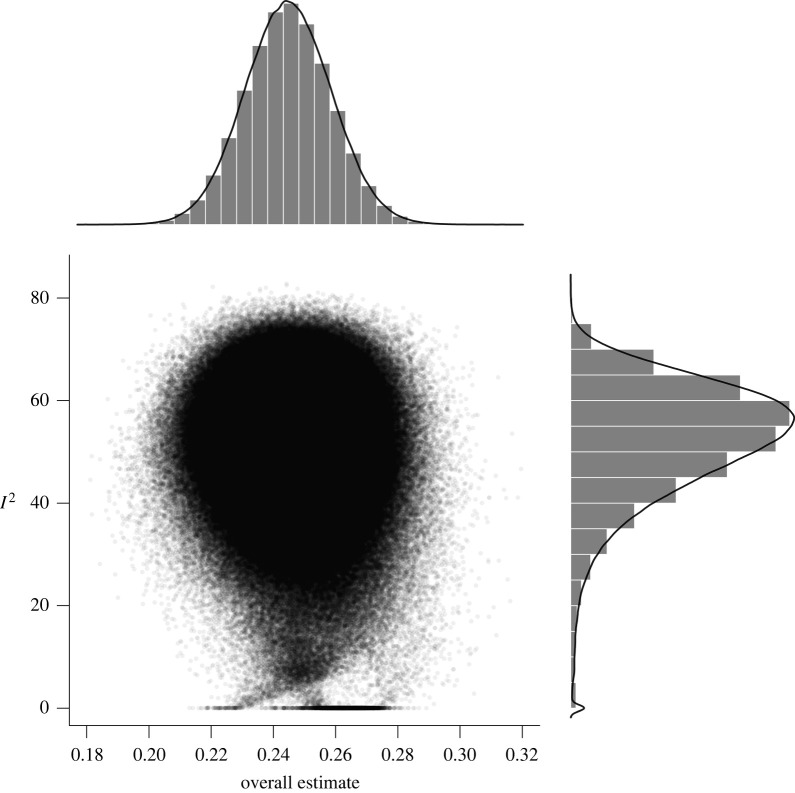

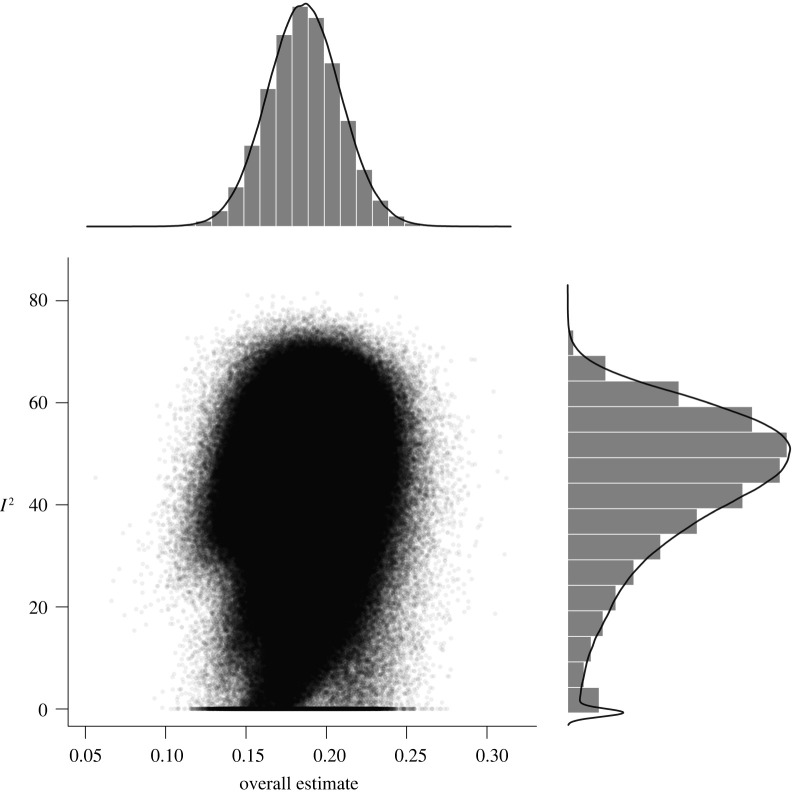

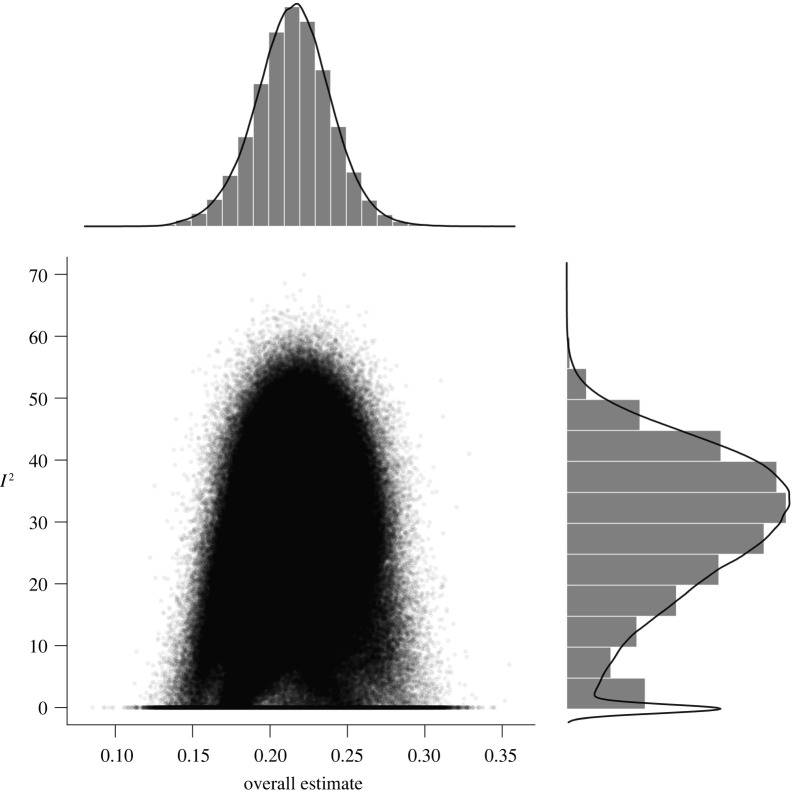

2.6.1 . Combinatorial meta-analysis

To this end, we first used a combinatorial meta-analysis to examine estimates for a large random selection of any possible subset of the 2k − 1 possible (not necessarily reasonable) combinations of the available data [20]. This approach can be interpreted as a sensitivity analysis by allowing the identification of outlier studies that overproportionally influence effect estimations.

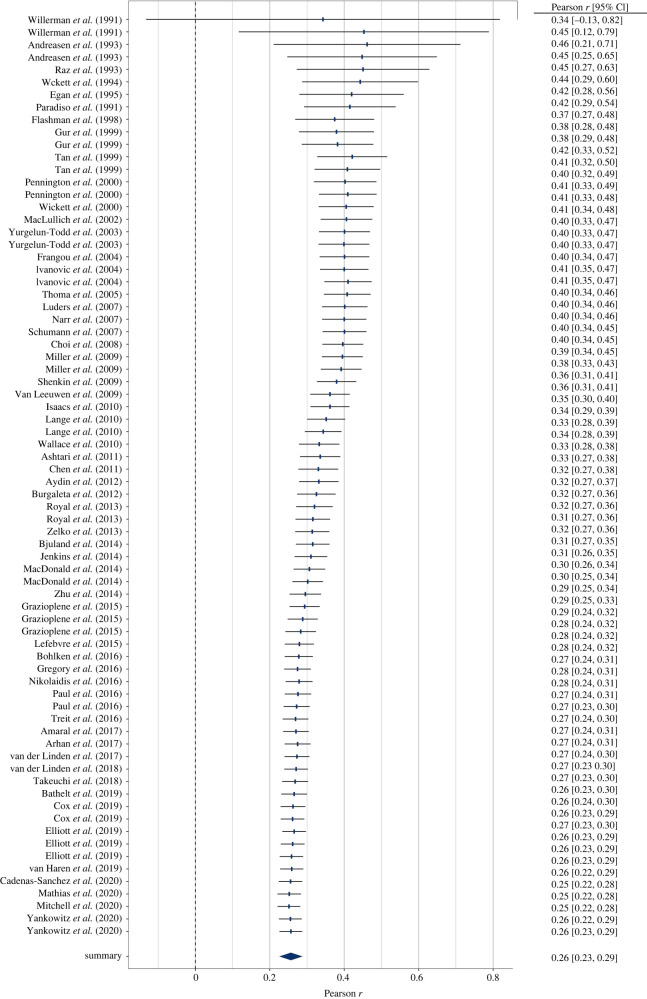

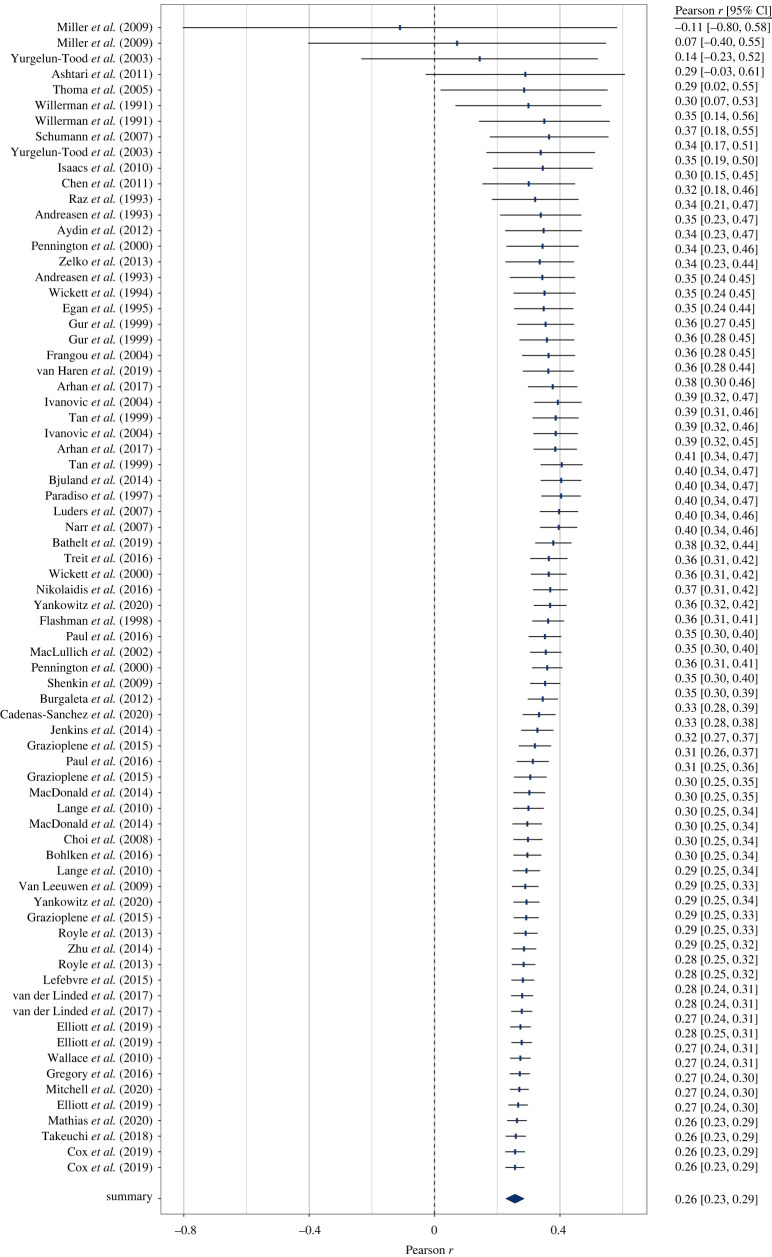

Consequently, 2123 and 271 (about 10 undecillions and 2 undecillions) combinations were possible for an exhaustive selection of full-scale IQ subsets for healthy and patient samples, respectively (270 and 245 as well as 249 and 233 combinations were possible for verbal and performance IQ). For our analyses, we randomly drew 100 000 subsets out of these possible combinations to illustrate outlier influences in GOSH plots (Graphic Display of Heterogeneity). Specifically, GOSH plots allow a visual inspection of summary effect distributions and their associated between-studies heterogeneity when any kind of (un)reasonable specification has been used. Moreover, numerical inspections of dispersion values (e.g. interquartile ranges) and the effect distribution permit an evaluation of the influence of moderating variables (i.e. narrow intervals and symmetrical distributions indicated well-interpretable summary effects).

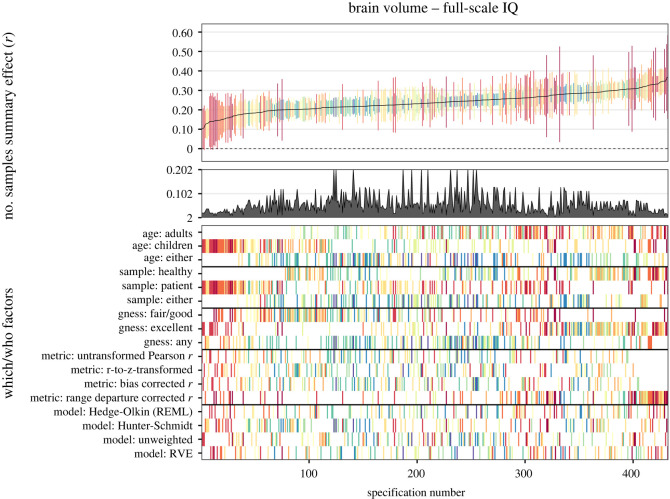

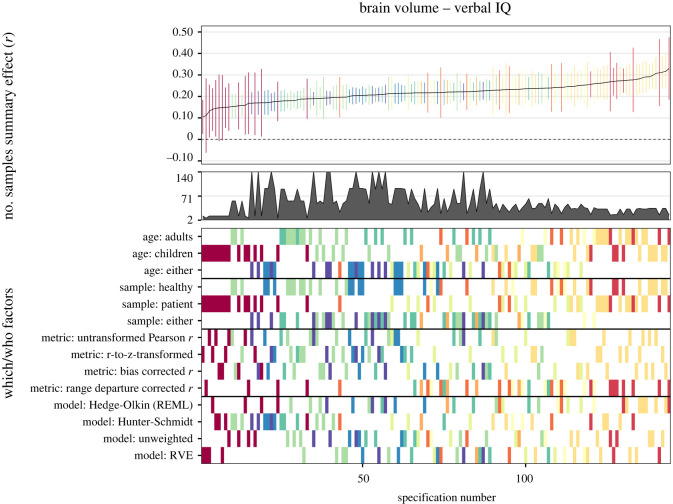

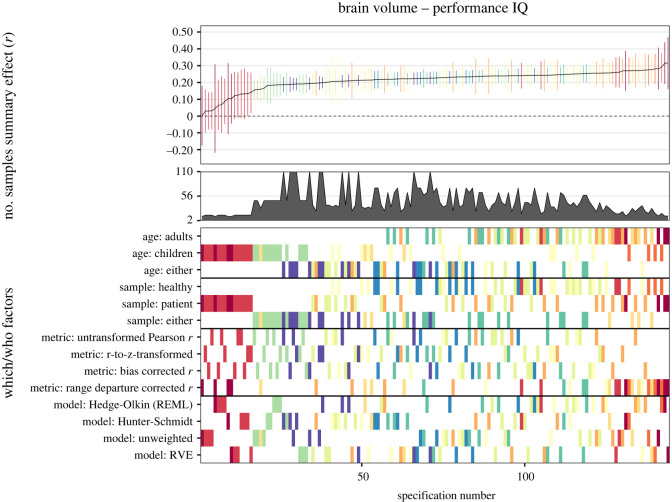

2.6.2 . Specification-curve meta-analysis

By means of another method, we examined several possible reasonable specifications. In our meta-analytic specification-curve analyses (see [14]), we introduced three which factors: (1) sample age: adults versus children/adolescents versus either; (2) sample type: healthy versus patient versus either; (3) g-ness (for full-scale IQ only): fair or good versus excellent versus either; and two how factors: (1) effect size type: non-transformed Pearson rs versus r-to-z-transformed effect size versus small sample bias corrected rs versus range departure corrected rs; (2) analysis approach: Hedges-Olkin random-effects estimation versus Hunter-Schmidt effect estimation versus unweighted estimation versus RVE).

Consequently, these potentially influential analytic choices yielded 3 × 3 × 3 = 27 ways for which data to analyze and 4 × 4 = 16 ways for how to do it, thus totaling 27 × 16 = 432 reasonable specifications. In our further analyses in the subsets of verbal and performance data only, this number was reduced to 144 reasonable specifications because g-ness was not relevant in these cases. Specifications that comprised less than two effect sizes were dropped from analyses.

2.7. Final sample

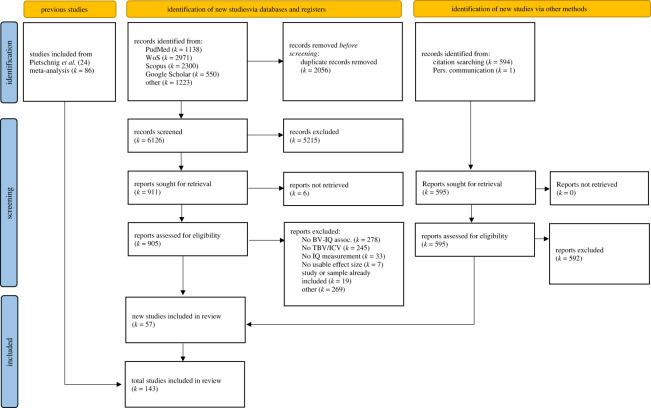

We included effect sizes of 86 studies from Pietschnig et al. [24] ([58] and [59] were presently excluded because (i) of duplicate effect size publication and (ii) brain-volume measurements had not been performed in vivo) as well as 57 newly identified studies. Because more recent studies were based on larger samples, this update more than tripled the included participant numbers compared to Pietschnig et al. [24], thus representing a crucial expansion of the empirical knowledge base. In all, we extracted 454 effect sizes including 194 independent samples for full-scale, 115 for verbal, and 82 for performance IQ associations (Ns = 26 764; 7667; and 5984; respectively). The majority of samples comprised healthy participants and about a third comprised patients (ks = 123 versus 71; 70 versus 45; 49 versus 33; Ns = 23 403 versus 5361; 5440 versus 2237; 4162 versus 1858 for healthy and patient samples for full-scale, verbal and performance IQ, respectively). A PRISMA flowchart for the study inclusion process is provided in figure 1 (for study characteristics, table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies. Note. NA = info not available; Review: 1 = included in McDaniel [23], 2 = included in Pietschnig et al. [24], 3 = included in Gignac & Bates [25], 4 = included in present update; Reporting: reported = published in a journal article, grey = published as thesis/dissertation, PC = result obtained via personal communication; FSIQ = full-scale IQ; Type of test: IQ assessment used in study; subtest abbreviations: arith = arithmetic, bd = block design, com = comprehension, ds = digit symbol, inf = information, lm = logical memory, lns = letter-number sequencing, mr = matrix reasoning, obj = object assembly, pc = picture completion, pic = picture arrangement, sim = similarities, span = digit span (b stand for backwards), ss = symbol search, ss p + f = spatial span forwards and backwards, vpa = verbal pair associates; domain indices of the Wechsler scales are abbreviated as follows: POI = perceptual organization index, PRI = perceptual reasoning index, PSI = processing speed index, VCI = verbal comprehension index, WMI = working memory index; full information explaining all abbreviations are available in the codebook and data files in supplemental materials. Published study outcomes with r = exactly 0 represent correlations set to zero, because no eligible numerical value was available.

| study | year | review | sample type | mean age | male ratio (%) | reporting | IQ domain | test | n | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yeo et al. [60] | 1987 | 2, 4 | patients | 38.40 | 34.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS | 41 | 0.007 |

| Yeo et al. [60] | 1987 | 2, 4 | patients | 38.40 | 34.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS verbal | 41 | 0.12 |

| Yeo et al. [60] | 1987 | 2, 4 | patients | 38.40 | 34.00 | reported | performance | WAIS performance | 41 | 0.06 |

| Willerman et al. [5] | 1991 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 18.90 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R: voc, sim, bd, pc | 20 | 0.33 |

| Willerman et al. [5] | 1991 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 18.90 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R: voc, sim, bd, pc | 20 | 0.51 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 38.00 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 30 | 0.44 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 38.00 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 37 | 0.40 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 2, 4 | healthy | 38.00 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 30 | 0.43 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 2,4 | healthy | 38.00 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 37 | 0.33 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 2, 4 | healthy | 38.00 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 30 | 0.30 |

| Andreasen et al. [61] | 1993 | 2, 4 | healthy | 38.00 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 37 | 0.43 |

| Raz et al. [62] | 1993 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 43.80 | 59.00 | reported | fluid | CFIT | 29 | 0.43 |

| Raz et al. [62] | 1993 | 2, 4 | healthy | 43.80 | 59.00 | reported | verbal | Extended Vocabulary (V3) | 29 | 0.10 |

| Castellanos et al. [63] | 1994 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 12.10 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WISC-R: voc | 46 | 0.33 |

| Harvey et al. [64] | 1994 | 2, 4 | patients | 35.60 | 38.00 | reported | verbal | NART | 26 | 0.38 |

| Harvey et al. [64] | 1994 | 2, 4 | patients | 31.10 | 77.00 | reported | verbal | NART | 48 | 0.24 |

| Harvey et al. [64] | 1994 | 2, 4 | healthy | 31.60 | 55.00 | reported | verbal | NART | 34 | 0.69 |

| Jones et al. [65] | 1994 | 2, 4 | healthy | 31.70 | 64.00 | reported | verbal | NART or WAIS-R verbal | 67 | 0.30 |

| Wickett et al. [66] | 1994 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | MAB | 40 | 0.40 |

| Wickett et al. [66] | 1994 | 2, 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | MAB verbal | 40 | 0.44 |

| Wickett et al. [66] | 1994 | 2, 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | performance | MAB performance | 40 | 0.28 |

| Bigler [67] | 1995 | 2, 4 | patients | 29.40 | 71.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 72 | −0.03 |

| Egan et al. [68] | 1995 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 22.50 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 40 | 0.31 |

| Egan et al. [68] | 1995 | 2, 4 | healthy | 22.50 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 40 | 0.21 |

| Egan et al. [68] | 1995 | 2, 4 | healthy | 22.50 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 40 | 0.22 |

| Haier et al. [69] | 1995 | 2, 4 | patients | 26.39 | 54.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 28 | 0.65 |

| Kareken et al. [70] | 1995 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 27.66 | 63.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 68 | 0.30 |

| Kareken et al. [70] | 1995 | 4 | patients | 29.75 | 63.00 | reported | verbal | COWA, Animal Naming, Boston Naming, Token Test, WRAT: Reading | 68 | 0.36 |

| Kareken et al. [70] | 1995 | 4 | healthy | 27.66 | 63.00 | reported | verbal | COWA, Animal Naming, Boston Naming, Token Test, WRAT: Reading | 68 | 0.24 |

| Kareken et al. [70] | 1995 | 4 | patients | 29.75 | 63.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd; Benton Line Orientation, Geometric Figure Drawings | 68 | 0.18 |

| Kareken et al. [70] | 1995 | 4 | healthy | 27.66 | 63.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd; Benton Line Orientation, Geometric Figure Drawings | 68 | 0.26 |

| Raz et al. [71] | 1995 | 2, 4 | patients | 35.20 | 77.00 | reported | FSIQ | WPPSI-R + BCS | 11 | −0.24 |

| Reiss et al. [72] | 1995 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.28 | 42.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-R or SB or BSID | 87 | 0.00 |

| Reiss et al. [72] | 1995 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.80 | 35.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-R or SB or BSID | 51 | 0.25 |

| Reiss et al. [73] | 1996 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 10.60 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 57 | 0.37 |

| Reiss et al. [73] | 1996 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.10 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 12 | 0.52 |

| Blatter et al. [74] | 1997 | 2, 4 | patients | NA | NA | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 22 | 0.57 |

| Blatter et al. [74] | 1997 | 2, 4 | patients | NA | NA | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 21 | 0.47 |

| Mori et al. [75] | 1997 | 2, 4 | patients | 70.20 | 38.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 60 | 0.40 |

| Mori et al. [75] | 1997 | 2, 4 | patients | 70.20 | 38.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 60 | 0.37 |

| Mori et al. [75] | 1997 | 2, 4 | patients | 70.20 | 38.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 60 | 0.37 |

| Paradiso et al. [76] | 1997 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 24.80 | 53.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 62 | 0.38 |

| Paradiso et al. [76] | 1997 | 2, 4 | healthy | 24.80 | 53.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R: voc | 62 | 0.27 |

| Paradiso et al. [76] | 1997 | 2, 4 | healthy | 24.80 | 53.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 62 | 0.32 |

| Paradiso et al. [76] | 1997 | 4 | healthy | 24.80 | 53.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R: span | 62 | 0.11 |

| Flashman et al. [77] | 1998 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 53.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 90 | 0.25 |

| Flashman et al. [77] | 1998 | 2, 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 53.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 90 | 0.16 |

| Flashman et al. [77] | 1998 | 2, 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 53.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 90 | 0.26 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R: voc, bd; CVLT, JLO | 40 | 0.40 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R: voc, bd; CVLT, JLO | 40 | 0.39 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R: voc; CVLT | 40 | 0.40 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R: voc; CVLT | 40 | 0.00 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 4 | healthy | 25.00 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd; JLO | 40 | 0.57 |

| Gur et al. [78] | 1999 | 4 | healthy | 27.00 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd; JLO | 40 | 0.35 |

| Leonard et al. [79] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 43.00 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 37 | 0.00 |

| Leonard et al. [79] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 42.00 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 33 | 0.00 |

| Leonard et al. [79] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 43.00 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R performance | 37 | 0.00 |

| Leonard et al. [79] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 42.00 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R performance | 33 | 0.00 |

| Tan et al. [80] | 1999 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 22.00 | 0.00 | reported | fluid | CFIT | 54 | 0.62 |

| Tan et al. [80] | 1999 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 22.00 | 100.00 | reported | fluid | CFIT | 49 | 0.28 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 21.60 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 11 | 0.00 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.50 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 13 | 0.00 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 21.80 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 10 | 0.00 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 21.80 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 10 | 0.00 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.50 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 25 | 0.00 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 21.63 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 45 | 0.31 |

| Warwick et al. [81] | 1999 | 2, 4 | patients | 21.55 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | Quick IQ Test [82] | 24 | 0.53 |

| Garde et al. [83] | 2000 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 80.70 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS | 22 | 0.22 |

| Garde et al. [83] | 2000 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 80.70 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS | 46 | 0.07 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 73.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III | 11 | −0.03 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 38.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III | 8 | 0.55 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 73.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III verbal | 11 | −0.04 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 38.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III verbal | 8 | 0.57 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 73.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III performance | 11 | −0.18 |

| Isaacs et al. [84] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 7.75 | 38.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III performance | 8 | 0.35 |

| Kumra et al. [85] | 2000 | 2, 4 | patients | 12.30 | 81.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-R or WAIS: voc, bd | 27 | 0.00 |

| Kumra et al. [85] | 2000 | 2, 4 | patients | 14.40 | 57.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-R or WAIS: voc, bd | 44 | 0.00 |

| Lawson et al. [86] | 2000 | 2, 4 | patients | NA | NA | reported | FSIQ | WISC-III or WPPSI-R or DAS or SB or GMDS | 47 | 0.43 |

| Pennington et al. [87] | 2000 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 19.06 | 44.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-R or WAIS-R FS | 36 | 0.31 |

| Pennington et al. [87] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 16.97 | 58.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-R or WAIS-R FS | 96 | 0.42 |

| Schoenemann et al. [88] | 2000 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 23.20 | 0.00 | PC | fluid | RSPM | 72 | 0.21 |

| Schoenemann et al. [88] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 23.20 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | MAB vocabulary | 36 | 0.12 |

| Wickett et al. [89] | 2000 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 24.97 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | MAB | 68 | 0.35 |

| Wickett et al. [89] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 24.97 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | MAB verbal | 68 | 0.33 |

| Wickett et al. [89] | 2000 | 2, 4 | healthy | 24.97 | 100.00 | reported | performance | MAB performance | 68 | 0.31 |

| Castellanos et al. [90] | 2001 | 2, 4 | patients | 9.70 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-R or WISC-III: voc, bd | 40 | 0.36 |

| Coffey et al. [91] | 2001 | 2, 4 | healthy | 74.85 | 38.00 | reported | verbal | Verbal fluecy Task | 319 | −0.06 |

| Coffey et al. [91] | 2001 | 2, 4 | healthy | 74.85 | 38.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 318 | 0.06 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 46 | −0.13 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | NA | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 30 | 0.08 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 2, 4 | patients | 18.80 | 87.00 | reported | FSIQ | unknown FS | 67 | 0.10 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 2, 4 | patients | 18.80 | 87.00 | reported | verbal | unknown verbal | 67 | 0.08 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.90 | 92.00 | reported | verbal | unknown verbal | 83 | −0.01 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 2, 4 | patients | 18.80 | 87.00 | reported | performance | unknown performance | 67 | 0.10 |

| Aylward et al. [92] | 2002 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.90 | 92.00 | reported | performance | unknown performance | 83 | 0.09 |

| MacLullich et al. [93] | 2002 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 67.80 | 100.00 | reported | fluid | RSPM | 95 | 0.39 |

| MacLullich et al. [93] | 2002 | 2, 4 | healthy | 67.80 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | NART | 97 | 0.30 |

| Nosarti et al. [94] | 2002 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 65.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 42 | 0.37 |

| Shapleske et al. [95] | 2002 | 1, 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 33.30 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 23 | 0.13 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 16.40 | 60.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-R or WAIS-R | 22 | −0.13 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.80 | 67.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-R or WAIS-R | 32 | −0.27 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.80 | 67.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-R or WAIS-R verbal | 32 | −0.28 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 16.40 | 60.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-R or WAIS-R verbal | 22 | −0.09 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.80 | 67.00 | PC | performance | WISC-R or WAIS-R performance | 32 | −0.19 |

| Collinson et al. [96] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 16.40 | 60.00 | PC | performance | WISC-R or WAIS-R performance | 22 | −0.17 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 8 | 0.46 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 7 | 0.17 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 7 | −0.67 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 7 | 0.67 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 39 | 0.34 |

| Giedd [97] | 2003 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | NA | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | unknown FS | 63 | 0.27 |

| Kesler et al. [98] | 2003 | 2, 4 | patients | 26.16 | 52.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 25 | 0.47 |

| Kesler et al. [98] | 2003 | 2, 4 | patients | 26.16 | 52.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 25 | 0.57 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | Shipley total | 24 | 0.20 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.50 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | Shipley total | 13 | 0.26 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | Shipley verbal | 24 | 0.17 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.50 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | Shipley verbal | 13 | 0.19 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: span | 24 | 0.19 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 4 | healthy | 14.50 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: span | 13 | 0.55 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ds | 24 | 0.07 |

| Yurgelun-Todd et al. [99] | 2003 | 4 | healthy | 14.50 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ds | 13 | 0.48 |

| Frangou et al. [100] | 2004 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 15.05 | 50.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-III or WAIS-III | 40 | 0.41 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.90 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | Wechsler FS | 38 | 0.24 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.90 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | Wechsler FS | 38 | 0.27 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.86 | 50.00 | PC | FSIQ | Wechsler FS | 16 | 0.49 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.60 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | Wechsler verbal | 38 | 0.20 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.90 | 0.00 | PC | performance | Wechsler performance | 38 | 0.21 |

| Isaacs et al. [101] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.90 | 100.00 | PC | performance | Wechsler performance | 38 | 0.15 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 49 | 0.37 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 47 | 0.55 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 49 | 0.33 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 47 | 0.55 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 49 | 0.38 |

| Ivanovic et al. [102,103] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 18.00 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-R performance | 47 | 0.52 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 43.62 | 47.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R or WAIS-III | 17 | 0.31 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 30.30 | 87.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R or WAIS-III | 15 | 0.07 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 30.30 | 87.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R or WAIS-III verbal | 15 | 0.30 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 43.62 | 47.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R or WAIS-III verbal | 17 | 0.19 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 30.30 | 87.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R or WAIS-III performance | 15 | 0.15 |

| Rojas et al. [104] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 43.62 | 47.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R or WAIS-III performance | 17 | 0.27 |

| Toulopoulou et al. [105] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 42.23 | 50.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 201 | 0.28 |

| Toulopoulou et al. [105] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 42.23 | 50.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 201 | 0.28 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.50 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV | 16 | 0.13 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 15.40 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV | 16 | −0.06 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 15.40 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV verbal | 16 | −0.17 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.50 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV verbal | 16 | 0.20 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | patients | 15.40 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV performance | 16 | 0.10 |

| Waiter et al. [106] | 2004 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.50 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III-R or WAIS-IV performance | 16 | 0.23 |

| Antonova et al. [107] | 2005 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.49 | 60.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III: voc | 44 | 0.16 |

| Antonova et al. [107] | 2005 | 2, 4 | healthy | 33.72 | 58.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III: voc | 43 | 0.24 |

| Lodygensky et al. [108] | 2005 | 2, 4 | healthy | 8.42 | 57.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-R | 21 | 0.46 |

| Lodygensky et al. [108] | 2005 | 2, 4 | patients | 8.58 | 53.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-R | 60 | 0.35 |

| Thoma et al. [109] | 2005 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 23.50 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | RPM, TrailsAB, WAIS-R: voc, bd, ds; VMRT, COWA | 19 | 0.27 |

| Debbané et al. [110] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.10 | 43.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WAIS-III | 41 | 0.16 |

| Debbané et al. [110] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.70 | 37.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WAIS-III | 43 | 0.16 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.41 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-III or WISC-III | 23 | 0.46 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 20.79 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-III or WISC-III | 24 | 0.30 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 20.79 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III or WISC-III verbal | 24 | 0.28 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.41 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III or WISC-III verbal | 23 | 0.55 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 20.79 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-III or WISC-III performance | 24 | 0.31 |

| Rojas et al. [111] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.41 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-III or WISC-III performance | 23 | 0.09 |

| Staff et al. [112] | 2006 | 1, 2, 4 | healthy | 79.50 | 61.00 | PC | fluid | RSPM | 102 | −0.10 |

| Staff et al. [112] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 79.50 | 61.00 | PC | verbal | NART | 102 | −0.14 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.77 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III | 13 | −0.11 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.16 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III | 38 | 0.02 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.08 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III | 12 | −0.14 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.16 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III verbal | 38 | 0.08 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.08 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III verbal | 12 | 0.23 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.77 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III verbal | 13 | −0.15 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.77 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III performance | 13 | 0.06 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.08 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III performance | 12 | −0.48 |

| Voelbel et al. [113] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.16 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III performance | 38 | −0.02 |

| Wozniak et al. [114] | 2006 | 2, 4 | healthy | 12.40 | 46.20 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 13 | 0.59 |

| Wozniak et al. [114] | 2006 | 2, 4 | patients | 12.30 | 50.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 14 | 0.41 |

| Chiang et al. [115] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 29.20 | 45.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS verbal | 39 | −0.02 |

| Chiang et al. [115] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | NA | NA | reported | verbal | WAIS verbal | 16 | −0.44 |

| Chiang et al. [115] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 29.20 | 45.00 | reported | performance | WAIS performance | 39 | 0.10 |

| Chiang et al. [115] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | NA | NA | reported | performance | WAIS performance | 16 | 0.41 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | NA | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 20 | −0.55 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.75 | NA | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 21 | 0.25 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.75 | NA | PC | verbal | WISC-III or WISC-IV: VCI | 21 | 0.30 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | NA | PC | verbal | WISC-III or WISC-IV: VCI | 20 | −0.20 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.75 | NA | PC | performance | WISC-III or WISC-IV: POI | 21 | 0.38 |

| DeBoer et al. [116] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | NA | PC | performance | WISC-III or WISC-IV: POI | 20 | −0.22 |

| Doernte [117] | 2007 | 4 | healthy | 58.50 | 0.00 | grey | FSIQ | HAWIE-R: sim, info, bd, pc | 18 | −0.23 |

| Doernte [117] | 2007 | 4 | healthy | 58.50 | 100.00 | grey | FSIQ | HAWIE-R: sim, info, bd, pc | 17 | 0.18 |

| Doernte [117] | 2007 | 4 | patients | 59.10 | 0.00 | grey | FSIQ | HAWIE-R: sim, info, bd, pc | 12 | −0.02 |

| Doernte [117] | 2007 | 4 | patients | 59.10 | 100.00 | grey | FSIQ | HAWIE-R: sim, info, bd, pc | 23 | −0.01 |

| Fine et al. [118] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 40.10 | 45.00 | PC | FSIQ | WASI | 44 | −0.11 |

| Fine et al. [118] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.47 | 63.00 | PC | FSIQ | WASI | 24 | 0.23 |

| Luders et al. [119] | 2007 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 28.48 | 45.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 62 | 0.28 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 40.80 | 90.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-III | 44 | 0.38 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.60 | 90.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-III | 43 | 0.32 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.60 | 90.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III verbal | 44 | 0.26 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 40.80 | 90.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III verbal | 44 | 0.40 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.60 | 90.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-III performance | 44 | 0.34 |

| Nakamura et al. [120] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 40.80 | 90.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-III performance | 43 | 0.29 |

| Narr et al. [121] | 2007 | 4 | healthy | 28.24 | 46.20 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS | 63 | 0.36 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 34.32 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 22 | 0.60 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 37.77 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 35 | 0.33 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.96 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 69 | 0.34 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 39.64 | 100.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 205 | 0.28 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.90 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R: voc | 68 | 0.43 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 34.32 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R: voc | 22 | 0.54 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 39.66 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R: voc | 202 | 0.28 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 37.77 | 100.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R: voc | 35 | 0.38 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 40.90 | 0.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 68 | 0.29 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 34.32 | 0.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 22 | 0.30 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | patients | 39.65 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 203 | 0.17 |

| Schottenbauer et al. [122] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 37.77 | 100.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R: bd | 35 | 0.17 |

| Schumann et al. [123] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 13.10 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 22 | 0.41 |

| Schumann et al. [123] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 13.10 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 22 | 0.38 |

| Schumann et al. [123] | 2007 | 2, 4 | healthy | 13.10 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 22 | 0.25 |

| Amat et al. [124] | 2008 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 31.50 | 56.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 27 | −0.11 |

| Amat et al. [124] | 2008 | 2, 4 | healthy | 31.50 | 56.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-R verbal | 27 | −0.29 |

| Amat et al. [124] | 2008 | 2, 4 | healthy | 31.50 | 56.00 | PC | performance | WAIS-R performance | 27 | 0.18 |

| Choi et al. [125] | 2008 | 4 | healthy | 21.60 | 54.30 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R | 164 | 0.35 |

| Ebner et al. [126] | 2008 | 2, 4 | patients | 34.52 | 68.00 | PC | verbal | MWT-B | 44 | 0.15 |

| Ebner et al. [126] | 2008 | 2, 4 | healthy | 32.45 | 51.00 | PC | verbal | MWT-B | 37 | −0.13 |

| Raz et al. [127] | 2008 | 2, 4 | healthy | 51.11 | 43.00 | PC | fluid | CFIT (form 2) | 55 | 0.18 |

| Raz et al. [127] | 2008 | 2, 4 | patients | 59.75 | 25.00 | PC | fluid | CFIT (form 2) | 32 | −0.02 |

| Raz et al. [127] | 2008 | 2, 4 | patients | 59.75 | 25.00 | PC | verbal | Vocabulary Test (V2 & V3) | 31 | 0.15 |

| Raz et al. [127] | 2008 | 2, 4 | healthy | 51.11 | 43.00 | PC | verbal | Vocabulary Test (V2 & V3) | 55 | 0.13 |

| Castro-Fornieles et al. [128] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 14.50 | 8.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-R: voc | 12 | 0.11 |

| Castro-Fornieles et al. [128] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 11.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-R: voc | 9 | 0.43 |

| Castro-Fornieles et al. [128] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 14.50 | 8.00 | PC | performance | WISC-R: bd | 12 | 0.38 |

| Castro-Fornieles et al. [128] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 14.60 | 11.00 | PC | performance | WISC-R: bd | 9 | 0.55 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 9.25 | 33.00 | reported | FSIQ | WJIII (GIA) | 12 | 0.23 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 12.08 | NA | reported | fluid | WJIII: thinking ability | 11 | −0.11 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.53 | 63.00 | reported | FSIQ | WJIII (GIA) | 16 | −0.30 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 12.08 | NA | reported | verbal | WJIII: Cog verbal ability | 11 | −0.65 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 9.25 | NA | reported | verbal | WJIII: Cog verbal ability | 5 | 0.84 |

| Miller et al. [129] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 16.53 | NA | reported | verbal | WJIII: Cog verbal ability | 6 | 0.76 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | 53.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 66 | 0.26 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.40 | 57.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WISC-IV | 47 | 0.26 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.40 | 57.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III or WISC-IV: VCI | 47 | 0.21 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | 53.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III or WISC-IV: VCI | 66 | 0.35 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 10.40 | 57.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III or WISC-IV: POI | 47 | 0.20 |

| Qiu et al. [130] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.50 | 53.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III or WISC-IV: PRI | 66 | 0.12 |

| Shenkin et al. [131] | 2009 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 78.40 | 29.00 | reported | FSIQ | MHT, RSPM, Verbal fluency, lm | 99 | 0.21 |

| Shenkin et al. [131] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 78.40 | 29.00 | reported | verbal | COWA (verbal fluency) | 107 | 0.13 |

| Van Leeuwen et al. [132] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 9.10 | 50.00 | reported | fluid | RSPM | 209 | 0.20 |

| Van Leeuwen et al. [132] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 9.10 | 50.00 | reported | verbal | WISC-III: comp | 209 | 0.33 |

| Van Leeuwen et al. [132] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 9.10 | 50.00 | reported | performance | WISC-III: POI | 209 | 0.28 |

| Van Leeuwen et al. [132] | 2009 | 4 | healthy | 9.10 | 50.00 | reported | performance | WISC-III: PSI | 209 | 0.12 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | HAWIE-R | 10 | 0.02 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 33.00 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | HAWIE-R | 25 | 0.15 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | HAWIE-R | 13 | 0.27 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | HAWIE-R verbal | 13 | 0.35 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 33.00 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | HAWIE-R verbal | 25 | 0.00 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | HAWIE-R verbal | 10 | −0.17 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | performance | HAWIE-R performance | 10 | 0.23 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | healthy | 33.00 | 0.00 | PC | performance | HAWIE-R performance | 25 | 0.24 |

| Weniger et al. [133] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 32.00 | 0.00 | PC | performance | HAWIE-R performance | 13 | 0.16 |

| Zeegers et al. [134] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 3.72 | 91.00 | reported | FSIQ | unknown FS | 21 | 0.06 |

| Zeegers et al. [134] | 2009 | 2, 4 | patients | 3.44 | 92.00 | reported | FSIQ | unknown FS | 10 | 0.73 |

| Betjemann et al. [135] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.40 | 52.00 | reported | verbal | WISC-R verbal | 142 | 0.14 |

| Betjemann et al. [135] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.40 | 52.00 | reported | performance | WISC-R performance | 142 | 0.42 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 33.34 | 42.00 | PC | FSIQ | Wechsler FS | 67 | 0.31 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 4 | patients | 36.09 | 35.00 | PC | FSIQ | Wechsler FS | 77 | 0.21 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 4 | patients | 36.09 | 35.00 | PC | verbal | Wechsler verbal | 77 | 0.28 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 33.34 | 42.00 | PC | verbal | Wechsler verbal | 67 | 0.23 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 4 | patients | 36.09 | 35.00 | PC | performance | Wechsler performance | 77 | 0.09 |

| Hermann [136] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 33.34 | 42.00 | PC | performance | Wechsler performance | 67 | 0.33 |

| Hogan et al. [137] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 68.69 | 53.00 | PC | fluid | RSPM | 234 | 0.11 |

| Hogan et al. [137] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 68.69 | 53.00 | PC | verbal | NART | 235 | 0.00 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 0.00 | PC | FSIQ | WISC-III or WAIS-III | 24 | 0.00 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-III or WAIS-III | 26 | 0.36 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 0.00 | PC | verbal | WISC-III or WAIS-III verbal | 24 | 0.00 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WISC-III or WAIS-III verbal | 26 | 0.48 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 0.00 | PC | performance | WISC-III or WAIS-III performance | 24 | 0.00 |

| Isaacs et al. [138] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.75 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WISC-III or WAIS-III performance | 26 | 0.19 |

| Lange et al. [139] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.88 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 166 | 0.22 |

| Lange et al. [139] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 10.95 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 143 | 0.23 |

| Wallace et al. [140] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.80 | 48.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 649 | 0.14 |

| Wallace et al. [140] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.80 | 48.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 649 | 0.13 |

| Wallace et al. [140] | 2010 | 2, 4 | healthy | 11.80 | 48.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 649 | 0.14 |

| Ashtari et al. [141] | 2011 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 18.50 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WRAT-III | 14 | 0.57 |

| Ashtari et al. [141] | 2011 | 2, 4 | patients | 19.30 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WRAT-III | 14 | 0.29 |

| Chen et al. [142] | 2011 | 4 | healthy | 22.56 | 44.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 27 | 0.02 |

| Chen et al. [142] | 2011 | 4 | patients | 23.07 | 46.70 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 30 | 0.68 |

| Chen et al. [142] | 2011 | 4 | patients | 23.02 | 27.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 37 | 0.41 |

| Kievit et al. [143] | 2011 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 21.10 | 36.00 | PC | FSIQ | WAIS-III | 80 | 0.29 |

| Kievit et al. [143] | 2011 | 2, 4 | healthy | 21.10 | 36.00 | PC | verbal | WAIS-III verbal | 80 | 0.23 |

| Tate et al. [144] | 2011 | 2, 4 | patients | 81.70 | 43.00 | PC | FSIQ | Shipley | 194 | 0.00 |

| Aydin et al. [145] | 2012 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.10 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-R | 30 | 0.40 |

| Aydin et al. [145] | 2012 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.10 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WISC-R verbal | 30 | 0.26 |

| Aydin et al. [145] | 2012 | 2, 4 | healthy | 15.10 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WISC-R performance | 30 | 0.34 |

| Burgaleta et al. [146] | 2012 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 19.88 | 44.00 | reported | FSIQ | 9 tests from APM, DAT-AR-5, PMR-R | 100 | 0.17 |

| Bigler et al. [147] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 10.66 | 58.00 | reported | performance | WISC-IV: PSI | 47 | 0.00 |

| Bigler et al. [147] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 10.67 | 68.00 | reported | performance | WISC-IV: PSI | 32 | 0.00 |

| Bigler et al. [147] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 10.14 | 58.00 | reported | performance | WISC-IV: PSI | 27 | 0.00 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-III: ins, span, mr, bd, ss, ds | 293 | 0.26 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 2, 3, 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-III: ins, span, mr, bd, ss, ds | 327 | 0.27 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: lns | 293 | 0.10 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: lns | 327 | 0.22 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: span b | 293 | 0.11 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: span b | 327 | 0.23 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: bd | 293 | 0.25 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: bd | 327 | 0.25 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: mr | 293 | 0.14 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: mr | 327 | 0.18 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ds | 293 | 0.22 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ds | 327 | 0.33 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.47 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ss | 293 | 0.17 |

| Royle et al. [148] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 72.60 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ss | 327 | 0.34 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 53.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS or WISC: voc, sim, pc, bd, arith, ds, ss | 36 | 0.25 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 14.60 | 49.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS or WISC: voc, sim, pc, bd, arith, ds, ss | 108 | 0.23 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 14.60 | 49.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS or WISC: voc, sim | 108 | 0.23 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 53.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS or WISC: voc, sim | 36 | 0.04 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 14.60 | 49.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS or WISC: arith, span | 108 | 0.26 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 53.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS or WISC: arith, span | 36 | 0.33 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 14.60 | 49.00 | reported | performance | WAIS or WISC: pc, bd | 108 | 0.21 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 53.00 | reported | performance | WAIS or WISC: pc, bd | 36 | 0.30 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | patients | 14.60 | 49.00 | reported | performance | WAIS or WISC: cod, sym | 108 | 0.09 |

| Zelko et al. [149] | 2013 | 4 | healthy | 14.90 | 53.00 | reported | performance | WAIS or WISC: cod, sym | 36 | −0.12 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 20.30 | 42.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-III | 60 | 0.36 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 20.10 | 41.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-III | 43 | 0.56 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 20.30 | 41.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: VCI | 42 | 0.44 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 20.30 | 41.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: WMI | 42 | 0.54 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 20.30 | 41.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-II: POI | 43 | 0.48 |

| Bjuland et al. [150] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 20.30 | 41.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-II: PSI | 43 | 0.48 |

| Grunewaldt et al. [151] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 10.17 | 34.80 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-III | 21 | 0.00 |

| Grunewaldt et al. [151] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 10.17 | 34.80 | reported | verbal | WISC-III: WMI | 21 | 0.00 |

| Jenkins et al. [152] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.70 | 41.70 | reported | FSIQ | WASI, WISC-III or WPPSI-R: voc, mr | 102 | 0.19 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.60 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 142 | 0.23 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.30 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 161 | 0.22 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.60 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 142 | 0.13 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.30 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 161 | 0.18 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.60 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 142 | 0.29 |

| MacDonald et al. [153] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 11.30 | 0.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 161 | 0.19 |

| McCoy et al. [154] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 13.00 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-IV (GAI) | 10 | 0.59 |

| McCoy et al. [154] | 2014 | 4 | patients | 13.00 | 0.00 | reported | FSIQ | WISC-IV (GAI) | 16 | 0.62 |

| Zhu et al. [155] | 2014 | 4 | healthy | 20.41 | 41.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-R (Chinese) | 316 | 0.10 |

| Boberg et al. [156] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 8.00 | 54.00 | grey | FSIQ | WISC-IV (Swedish) | 10 | 0.69 |

| Boberg et al. [156] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 8.20 | 35.80 | grey | FSIQ | WISC-IV (Swedish) | 9 | 0.00 |

| Boberg et al. [156] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 8.30 | 50.00 | grey | FSIQ | WISC-IV | 21 | 0.00 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 26.20 | 51.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-IV: voc, sim, mr, bd | 285 | 0.28 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 23.50 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-IV: voc, sim, mr, bd | 107 | 0.08 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 21.70 | 54.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 125 | 0.04 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 26.20 | 51.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-IV: voc, sim | 285 | 0.18 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 21.70 | 54.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 125 | 0.04 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 23.50 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: voc, sim | 107 | 0.10 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 26.20 | 51.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-IV: mr, bd | 285 | 0.30 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 21.70 | 54.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 125 | 0.04 |

| Grazioplene et al. [157] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 23.50 | 100.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: mr, bd | 107 | 0.04 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 17.00 | 83.00 | reported | FSIQ | Wechsler | 366 | 0.23 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | patients | 16.60 | 88.00 | reported | FSIQ | Wechsler | 328 | 0.04 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | patients | 16.60 | 88.00 | reported | verbal | unknown verbal | 241 | 0.08 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 17.00 | 83.00 | reported | verbal | unknown verbal | 297 | 0.22 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | patients | 16.60 | 88.00 | reported | performance | unknown performance | 241 | 0.17 |

| Lefebvre et al. [158] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 17.00 | 83.00 | reported | performance | unknown performance | 297 | 0.18 |

| Paul et al. [159] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 24.57 | 0.00 | reported | verbal | Reading Span, Rotation Span, Symmetrie Span | 90 | 0.25 |

| Paul et al. [159] | 2015 | 4 | healthy | 24.07 | 100.00 | reported | verbal | Reading Span, Rotation Span, Symmetrie Span | 121 | 0.18 |

| Walters et al. [160] | 2015 | 4 | patients | 17.32 | 100.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS or WISC: voc, mr | 178 | 0.19 |

| Ballester-Plane et al. [161] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 25.10 | 67.00 | reported | FSIQ | RCPM | 30 | 0.73 |

| Ballester-Plane et al. [161] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 25.10 | 67.00 | reported | verbal | PPVT-III | 30 | 0.71 |

| Ballester-Plane et al. [161] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 25.10 | 67.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 30 | 0.72 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.69 | 42.00 | reported | FSIQ | WAIS-III: ds, bd, arith., span, inf | 164 | 0.26 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.70 | 42.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: inf | 164 | 0.18 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.70 | 42.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: arith | 164 | 0.26 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.70 | 42.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: span | 164 | 0.00 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.70 | 42.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: bd | 164 | 0.31 |

| Bohlken et al. [162] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 32.70 | 42.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: ds | 164 | 0.12 |

| Ferreira et al. [163] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 45.10 | 49.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: voc | 73 | 0.36 |

| Ferreira et al. [163] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 45.10 | 49.00 | reported | verbal | WAIS-III: inf | 73 | 0.50 |

| Ferreira et al. [163] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 45.10 | 49.00 | reported | performance | WAIS-III: bd | 73 | 0.33 |

| Gregory et al. [164] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 14.70 | 57.00 | reported | FSIQ | Conditional Exclusion, Emotional Differentiation, Emotional Identification, Face Memory, Letter N-Back, Line Orientation, Matrix Reasoning, Verbal Reasoning, Visual Object Learning, Word Memory; WRAT: Reading | 662 | 0.24 |

| Monson et al. [165] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 7.50 | 50.00 | reported | FSIQ | WASI | 134 | 0.26 |

| Gregory et al. [164] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 7.50 | 50.00 | reported | verbal | WASI verbal | 134 | 0.11 |

| Gregory et al. [164] | 2016 | 4 | patients | 7.50 | 50.00 | reported | performance | WASI performance | 134 | 0.31 |

| Nikolaidis et al. [166] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 21.15 | 34.00 | reported | fluid | RAPM, Shipley Abstraction, Letter Sets, Spatial Relations, Paper Folding, Form Boards | 71 | 0.44 |

| Nikolaidis et al. [166] | 2016 | 4 | healthy | 21.15 | 34.00 | reported | verbal | Visual Short-Term Memory, Spatial Working Memory, Running Span | 71 | 0.13 |