Abstract

Background

Rheumatological manifestations following COVID-19 are various, including Reactive Arthritis (ReA), which is a form of asymmetric oligoarthritis mainly involving the lower limbs, with or without extra-articular features. The current case series describes the clinical profile and treatment outcome of 23 patients with post-COVID-19 ReA.

Methods

A retrospective, observational study of patients with post-COVID-19 arthritis over one year was conducted at a tertiary care centre in India. Patients (n = 23) with either a positive polymerase chain reaction test for SARS-CoV2 or an anti-COVID-19 antibody test were included. Available demographic details, musculoskeletal symptoms, inflammatory markers, and treatment given were documented.

Results

Sixteen out of 23 patients were female. The mean age of the patients was 42.8 years. Nineteen patients had had symptomatic COVID-19 infection in the past. The duration between onset of COVID-19 symptoms and arthritis ranged from 5 to 52 days with a mean of 25.9 days. The knee was the most involved joint (16 out of 23 cases). Seven patients had inflammatory lower back pain and nine had enthesitis. Most patients were treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids – either depot injection or a short oral course. Three patients required treatment with hydroxychloroquine and methotrexate which were eventually stopped. No relapse was reported in any of the patients.

Conclusion

On combining our data with 21 other case reports of ReA, a lower limb predominant, oligoarticular, asymmetric pattern of arthritis was seen with a female preponderance. The mean number of joints involved was 2.8. Axial symptoms and enthesitis were often coexistent. Treatment with NSAIDs and intra-articular steroids was effective. However, whether COVID-19 was the definitive aetiology of the arthritis is yet to be proven.

Keywords: COVID-19 reactive arthritis, Post COVID-19 arthritis, Post COVID-19 ReA

Abstract

Antecedentes

Las manifestaciones reumatológicas posteriores al COVID-19 son diversas, entre ellas, la artritis reactiva, que es una forma de oligoartritis asimétrica que afecta principalmente a los miembros inferiores, con o sin características extraarticulares. La serie de casos actual describe el perfil clínico y el resultado del tratamiento de 23 pacientes con artritis reactiva posterior a COVID-19.

Métodos

Se realizó un estudio observacional retrospectivo de pacientes con artritis post-COVID-19 durante un año en un centro de atención terciaria en India. Se incluyeron pacientes (n = 23) con una prueba de reacción en cadena de la polimerasa positiva para SARS-CoV-2 o una prueba de anticuerpos anti-COVID-19. Se documentaron los detalles demográficos disponibles, los síntomas musculoesqueléticos, los marcadores inflamatorios y el tratamiento administrado.

Resultados

Dieciséis de los 23 pacientes eran mujeres. La edad media de los pacientes fue de 42,8 años. Diecinueve pacientes habían tenido infección sintomática por COVID-19 en el pasado. La duración entre el inicio de los síntomas de COVID-19 y la artritis osciló entre 5 y 52 días, con una media de 25,9 días. La rodilla fue la articulación más comúnmente involucrada (16 de 23 casos). Siete pacientes tenían dolor lumbar inflamatorio y 9 tenían entesitis. La mayoría de los pacientes fueron tratados con medicamentos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos y esteroides, ya fuera una inyección de depósito o un ciclo oral corto. Tres pacientes requirieron tratamiento con hidroxicloroquina y metotrexato, que finalmente se suspendieron. No se reportaron recaídas en ninguno de los pacientes.

Conclusión

Al combinar nuestros datos con otros 21 informes de casos de artritis reactiva, se observó un patrón de artritis oligoarticular asimétrico predominante en las extremidades inferiores con predominio femenino. El número medio de articulaciones afectadas fue de 2,8. A menudo coexistían síntomas axiales y entesitis. El tratamiento con antiinflamatorios no esteroideos y esteroides intraarticulares fue eficaz. Sin embargo, aún no se ha demostrado si el COVID-19 fue la etiología definitiva de la artritis.

Palabras clave: Artritis reactiva por COVID-19, Artritis post-COVID-19, Artritis reactiva post-COVID-19

Introduction

Immune-mediated manifestations of Corona Virus Disease-19 (COVID-19) have been reported, among which vasculitis, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, myositis, lupus, and arthritis are the major rheumatological ones.1 Mechanisms underlying the development of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases like reactive arthritis (ReA) after COVID-19 infection are yet to be elucidated properly. Transient virus-mediated immunosuppression along with high cytokine levels, especially interleukin-17, which is elevated in ReA, may be responsible for the development of ReA.2, 3 Humoral response to viral particles acting as antigens and deposition of these immune complexes within the joints might be responsible for the development of arthritis.4 Molecular mimicry is also another mechanism proposed in the pathogenesis of viral arthritis and COVID-19 related immunological consequences (but not arthritis specifically).5 However, further studies on pathomechanisms of arthrogenicity of coronavirus are required.

ReA is a form of asymmetric oligoarthritis mostly involving the lower limbs, with or without extra-articular features, usually predated by an infection of the gastrointestinal or urogenital tract. Symptoms develop 1–3 weeks after the infection and apart from arthritis, conjunctivitis, dactylitis, enthesitis, and inflammatory lower back pain may occur. Classically, ReA is known to occur after bacterial infections like Chlamydia,6 ReA can rarely be associated with streptococcal, staphylococcal, and even chlamydial respiratory infections.7, 8 To the best of our knowledge, ReA triggered by respiratory viral infections have not been reported in the pre-coronavirus era. Viral infections can be associated with musculoskeletal symptoms in the acute phase, but the development of ReA is rare. Since the emergence of coronavirus in late 2019, a few case reports of ReA after COVID-19 infection have been reported.4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 Amongst inflammatory arthritis, other reported conditions after COVID-19 infection is rheumatoid arthritis and seronegative spondyloarthropathy.28

Here, we present a case series of ReA after a definitive COVID-19 infection.

Methods

A retrospective study of patients presenting with oligo or polyarthritis to the Rheumatology outpatient department of a tertiary care centre from June 2020 to February 2021 was conducted. As there are no definitive criteria for diagnosing reactive arthritis, it was diagnosed based on the clinical presentation of arthritis following a documented COVID-19 infection. Cases were collected based on author recall and review of the database. Patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloarthropathy, psoriatic arthritis, gout, Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), osteoarthritis was excluded. Patients were prior history of arthritis were excluded. Patients who tested positive for Antinuclear Antibody, Rheumatoid Factor, anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide were excluded. Only patients with a documented history of COVID-19 illness [by Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) testing] 1–8 weeks before symptoms or those with positive COVID-19 antibody test (done at the discretion of the treating physician) were included. The COVID-19 antibody test comprised of antibody Immunoglobulin (Ig) G measured by chemiluminescent microparticle assay and total antibodies (IgG and IgM) using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. The cut off indices for these tests were 1.4 and 1 respectively. None of the patients had been previously vaccinated against COVID-19. Patients with a history suggestive of reactive arthritis but without documented evidence of COVID-19 (both PCR and antibody-negative) were excluded. Available demographic details and information on the number and pattern of joints (with clinical synovitis) involved, inflammatory markers and treatment were collected. For patients where a doubt regarding synovitis in a particular joint existed, an ultrasound examination was performed to confirm the same. Patients were questioned about a relapse of symptoms on follow up visits. Ethical clearance has been obtained for the study from the Institutional ethical committee (IPGME&R Research Oversight Committee; IPGME&R/IEC/2021/558; dated 28th September 2021).

Results

A total of 23 patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The available demographic details, details of COVID-19 serology, and musculoskeletal symptoms are given in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 14 patients with post COVID ReA.

| Patient no. | Age | Sex | Comorbidities | History of COVID | Days between onset of COVID and articular symptoms | PCR positive | COVID antibody positivity | CRP (normal value) | Joints involved | No. of joints involved | Inflammatory lower back pain | Enthesitis (site) | Other associated symptoms | Treatment received |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 19 | F | – | Yes | 20 | Yes | Not checked | Left knee | 1 | Yes | Yes (chest wall) | Myalgia | NSAIDs, low dose steroids | |

| 2 | 37 | F | Hypothyroidism | Yes | 21 | Yes | Not checked | 0.51 (<0.3) | Bilateral knees | 2 | Yes | Yes (Achilles tendinitis) | – | NSAIDs |

| 3 | 61 | F | – | Yes | 25 | Yes | Not checked | Bilateral knees | 2 | Yes | Yes (chest wall) | Myalgia | NSAIDs | |

| 4 | 69 | M | – | Yes | 20 | Yes | Not checked | Both shoulders and ankles, left knee | 5 | Yes | Yes (Achilles tendinitis) | – | NSAIDs, low dose steroids, hydroxychloroquine | |

| 5 | 41 | F | Hypertension | Yes | 12 | Yes | 7.4 (<5) | Both ankles, knees and left wrist | 5 | No | No | – | NSAIDs, low dose steroids | |

| 6 | 45 | F | Diabetes, hypertension | No | – | Yes | 3.2(<5) | Bilateral knees, ankles and wrists | 6 | No | Yes (mid foot) | – | Low dose steroids, methotrexate | |

| 7 | 47 | F | – | Yes | 10 | Yes | 15.9(<5) | Bilateral ankle joints | 2 | No | No | – | NSAIDs, IACS | |

| 8 | 55 | F | – | Yes | 50 | Yes | Bilateral knees, ankles | 4 | No | No | Myalgia | Depot steroids | ||

| 9 | 64 | M | – | No | – | Yes | Bilateral knees | 2 | Yes | No | – | NSAIDs | ||

| 10 | 49 | M | – | No | – | Yes | 3.9 (<5) | Bilateral wrists, MCP, left ankle | – | No | Yes (Achilles tendinitis) | – | NSAID, depot steroid | |

| 11 | 55 | F | – | No | – | Yes | Bilateral knees | 2 | No | No | – | NSAIDs | ||

| 12 | 36 | F | – | Yes | 5 | Yes | Not checked | 47 (<5) | Bilateral ankles | 2 | No | No | – | NSAIDs, depot steroids |

| 13 | 28 | F | – | Yes | 27 | Yes | Normal | Bilateral ankles and wrists | 4 | No | No | Erythematous skin rash | NSAIDs | |

| 14 | 58 | F | Hypertension | Yes | 15 | Yes | Not checked | Normal | Left knee | 1 | No | No | – | NSAIDs |

| 15 | 35 | F | – | Yes | 42 | Yes | Not checked | 86 (<6) | Bilateral knees and ankles | 4 | No | No | – | NSAIDs, oral steroids |

| 16 | 36 | M | – | Yes | 22 | Yes | Not checked | 12 (<6) | Left knee, right ankle | 2 | No | No | – | NSAIDs |

| 17 | 20 | M | – | Yes | 18 | Yes | Yes | Left ankle, right knee, bilateral first MCPs | 4 | Yes | No | – | NSAIDs, IACS | |

| 18 | 21 | F | – | Yes | 45 | Yes | Not checked | Bilateral wrists, right knee and ankle, left elbow | 5 | Yes | Yes (Bilateral Achilles tendinitis) | Bilateral conjunctivitis | NSAIDs | |

| 19 | 48 | F | – | Yes | 30 | Yes | Not checked | Left wrist and shoulder, right ankle | 3 | No | No | – | NSAIDs | |

| 20 | 45 | M | – | Yes | 21 | Yes | Not checked | Left ankle, right 2nd MCP and PIP, left 3rd MCP | 4 | No | No | – | NSAIDs | |

| 21 | 26 | F | – | Yes | 52 | Yes | Not checked | Left knee | 1 | No | Yes (left Achilles tendinitis) | – | NSAIDs | |

| 22 | 56 | F | Hypertension | Yes | 30 | Yes | Not checked | Bilateral wrists, knees, ankles and left shoulder | 7 | No | No | – | NSAIDs, oral steroids, hydroxychloroquine | |

| 23 | 34 | M | – | Yes | 28 | Yes | Not checked | 21 (<6) | Left ankle | 1 | No | Yes (Left Achilles tendinitis) | – | NSAIDs |

CRP, C-reactive protein; F, female; IgG, immunoglobulin G; M, male; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Sixteen out of 23 patients were female. The age of the patients ranged from 19 to 69 years (mean 42.8 ± 14.1 years). Nineteen patients had a past history of symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, with fever being the commonest symptom, present in all patients. Only 2 patients required hospitalisation for the management of COVID-19 (patients 2, and 3). Four patients had no definitive symptom of COVID-19 but antibody tests were ordered by the treating physician because of similarity of symptoms with patients with documented preceding COVID-19 infection. In patients with prior symptoms, the duration between onset of fever and arthritis ranged from 5 to 52 (n = 19) days with a mean of 25.9 (± 12.8) days. Knee was the most commonly involved joint. Knee joint involvement was seen in 16 out of 23 patients, and bilateral knee joint was affected in 9 out of those 16 cases. Ankles were involved in 15 and wrists in 7 out of 23 patients. Seven patients had inflammatory low back pain fulfilling the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society criteria29 and 9 had enthesitis. The Achilles tendon was the most common site of enthesitis followed by chest wall enthesitis. Amongst other features of reactive arthritis, only bilateral conjunctivitis was present in one patient. Most patients were treated with Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) and steroids (either depot injection or a short oral course). Three patients required prolonged treatment – two with hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 5 mg/kg/day and one with methotrexate 15 mg/week because of persistent joint pain after steroid tapering. HCQ was discontinued after 4 months and methotrexate after 5 months of treatment. There was no relapse of symptoms in any of the above-mentioned patients.

Discussion

COVID-19 associated rheumatological complaints include myalgia, arthralgia and fatigue which can occur either during or after the infection.28, 30 Arthritis occurring a few days after recovery has been reported in the form of ReA, acute arthritis or post-viral arthritis. However, apart from the serologic evidence of past COVID-19 infection, the attribution of the arthritis to COVID-19 is partly speculative and cannot be done beyond doubt. It is also possible that the arthritis is a part of a prolonged COVID infection-called as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. In our series, 23 patients presented with arthritis after a documented COVID-19 infection. Twenty-one cases of arthritis after COVID-19 are reported in the literature4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of 21 reported cases of post COVID ReA.

| Author | Age | Sex | Documented COVID | Duration between COVID and articular symptoms | Joints involved | No. of joints involved | CRP | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yokogawa et al.4 | 57 | M | Yes | 17 | Left wrist, right shoulder, bilateral knees | 4 | 4.8 mg/dL | Spontaneous resolution |

| Parisi et al.9 | 58 | F | Yes | 25 | Ankle arthritis, Achilles tendinitis | 1 | 7.36 mg/L (0–5) | NSAIDs |

| Ono et al.10 | 50s | M | Yes | 22 | Bilateral ankles, right Achilles tendinitis | 2 | 7.4 mg/dL (0–0.14) | NSAIDs, IACS |

| Waller et al.11 | 16 | F | Yes | 14 | MCPs, wrists, shoulders, hips, knees | – | <1 | – |

| Jali12 | 39 | F | Yes | 21 | DIP, PIP of hands | – | Normal | NSAIDs |

| Coath et al.13 | 53 | M | Yes | – | Inflammatory back pain | – | 13 mg/l (<10) | IM steroids, NSAIDs |

| Liew et al.14 | 47 | M | Yes | 3 | Right knee | 1 | NSAIDs, IACS | |

| Saricaoglu et al.15 | 73 | M | Yes | 22 | Left 1st MTP, bilateral PIP and DIP of toes | 5 | Markedly elevated | NSAIDs |

| Danssaert et al.16 | 37 | F | Yes | 12 | Right hand (tenosynovitis) | – | Normal | Opioids, topical NSAIDs |

| Fragata et al.17 | 41 | F | Yes | 28 | PIP, DIP, MCP | – | Normal | Oral steroids, NSAIDs |

| Gasparotto et al.18 | 60 | M | Yes | 32 | Right ankle, knee, hip | 3 | 237 mg/dL (<6) | NSAIDs |

| Hønge et al.19 | 53 | M | Yes | 21 | Right knee, both ankles and the lateral side of the left foot | 3 | 327 mg/dL | NSAIDs, oral steroid |

| Kocyigit et al.20 | 53 | F | Yes | 29 | Left knee | 1 | 10.8 mg/dL (<10 mg/dL) | NSAIDs |

| Schenker et al.21 | 65 | F | Yes | 10 | Bilateral knees, ankles and wrists | 6 | 34.7 mg/dL | Prednisolone |

| Di Carlo et al.22 | 55 | M | Yes | 37 | Right ankle | 1 | 5.6 mg/dL | Methylprednisolone |

| Hasbani et al.23 | 25 | M | Yes | 19 | Inflammatory back pain, left ankle and right elbow | 2 | 207 mg/L | Oral prednisolone, sulphasalazine |

| Hasbani et al.23 | 57 | M | Yes | 30 | Left wrist | 1 | 28.9 mg/L | Oral prednisolone, NSAIDs |

| Sureja et al.24 | 27 | F | Yes | 14 | Bilateral knees, ankles, midfoot, right wrist, MCPs,PIPs | Approximately 10 | - | NSAIDs |

| Shokraee et al.25 | 58 | F | Yes | 15 | Right hip | 1 | 6.5 mg/L | NSAID, prednisolone |

| Gibson et al.26 | 37 | M | Yes | 35 | Bilateral wrists and PIPs | Approximately 5 | 25 mg/dL (5 mg/dL) | Oral prednisolone and NSAIDs |

| Ghauri et al.27 | 34 | M | Yes | 15 | Right knee | 1 | Elevated | NSAID, IACS |

CRP, C-reactive protein; DIP, distal interphalangeal; F, female; IACS, intra-articular corticosteroids; M, male; MCP, metacarpophalangeal; MTP, metatarsophalangeal; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PIP, proximal interphalangeal.

Out of these 21 cases, 12 were male and 9 were female. However, in our cohort, a majority of the patients (16 out of 23) were women. The age group of previously reported 21 patients varied from 16 to 73 years which was similar to what was reported by us. The duration between onset of COVID-19 symptoms and arthritis symptoms varied from 3 to 37 days. Although the patient who developed symptoms in 3 days was concurrently positive for COVID-19, the authors state that he might have been tested later in the course of his disease as evidenced by the high Cycle threshold value in RT-PCR.15

From the pooled data available from 44 patients (23 from our cohort and 21 from previous reports), 25 were female and 19 were male. The mean age of the population was 45 ± 14.24 years. The mean number of days from the onset of COVID-19 symptoms to the onset of arthritis was (n = 39) was 23.4 ± 11.16 days.

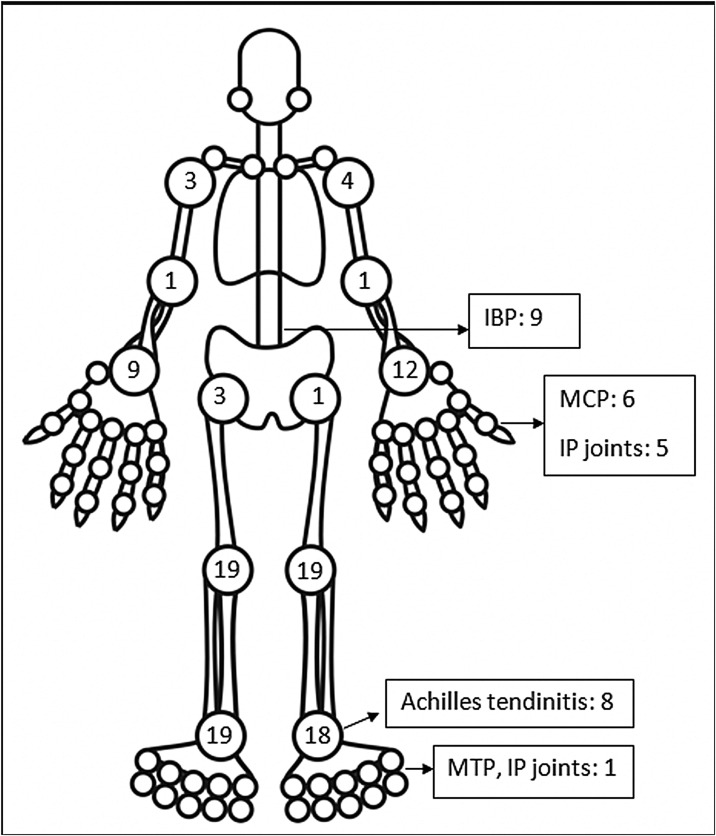

The pattern of joint involvement in the 21 reported cases4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 showed arthritis affecting knees and ankles in 9 and 8 patients respectively (shown in Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Frequency of joint involvement in post-COVID ReA patients.

Small joints of the hands were involved in 7 of the 21 reported cases. Few cases were limited to arthritis of the small joints of the hands or feet12, 15, 16, 17 which is unusual in reactive arthritis. Our series showed a lower limb predominant arthritis with only three patients having arthritis of the small joints of the hand. Out of the total 42 cases of ReA with peripheral arthritis following COVID-19 patients, 29 (69.05%) had oligoarthritis with involvement of fewer than 5 joints, and 13 (30.2%) had polyarthritis. One case had only inflammatory low back pain (IBP) with no articular involvement13 and another had right-hand tenosynovitis.16 Eleven patients had monoarthritis. On reviewing the pooled data, the exact number of joints involved were available for 36 patients. The mean number of joints involved was 2.8 ± 1.7. An asymmetric pattern of joint involvement is typical of ReA, and we found that out of 40 patients with information about symmetricity of joint peripheral joint involvement, 27 had asymmetric arthritis and 34 had symmetric arthritis.

IBP was present in 7 of our patients and two in the rest of the reported cases (who were also Human Leucocyte Antigen- B27 (HLA-B27) positive).13, 23 Of the reported cases in which HLA-B27 was tested, 4 patients tested positive.13, 21, 23 A Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the sacroiliac joints and an HLA-B27 test could have added an informative aspect to the management and follow up of these patients. Enthesitis involving the chest wall and Achilles’ tendons was present in 11 out of 44 patients. Enthesitis and IBP were coexistent in 5 patients. This leads us to believe that these patients might be a group susceptible to developing spondyloarthropathy. These patients will be kept under surveillance. The low incidence of back pain and enthesitis reported in the case reports might be due to the prompt response to NSAIDs given for arthritis or due to steroids which the patient might have received for COVID-19.

The level of C-Reactive Protein (CRP) was normal in some and elevated in some patients. Most of the patients were treated with NSAIDs and/or either intra-articular corticosteroid (IACS) injection or systemic steroids. One of our patients (Patient No. 13) had a diffuse erythematous, maculopapular, non- pruritic rash during the presentation which resolved subsequently (Supplementary Fig. S1) and another had bilateral conjunctivitis. Other symptoms associated with ReA like balanitis, and urethritis were absent in our patients but one case report had balanitis.15

Certain limitations of our study need to be addressed. The small sample size of 23 patients was due to the inability to test for COVID-19 antibodies in some patients with suspected post-COVID-19 ReA. The patients were recruited by the author recall posing the issue of recall bias. Testing for HLA-B-27 and MRI of sacroiliac joints for patients with inflammatory back pain was not done. Infections causing ReA like Yersinia, Salmonella, Shigella could not be definitively ruled out, although the patients were questioned for a preceding history of a urinary tract infection or gastroenteritis. The possibility of the symptoms being an initial manifestation of other inflammatory arthritides cannot be conclusively ruled out without long term follow up of these patients. Synovial fluid analysis was not done for any of the patients, hence it was not possible to completely rule out crystal arthropathy. To conclude definitively that COVID-19 is responsible for the arthritis in these patients is difficult and is a hypothesis pending to be proven. Despite these limitations, this is probably the largest case series describing ReA following COVID-19 infection to date. Further studies are required to gather more knowledge regarding post-COVID-19 reactive arthritis.

Conclusion

Herein, we report 23 cases of reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. On combining this data with other 21 reported cases of ReA we found that it occurred more commonly in females. A lower limb predominant, oligoarticular, asymmetrical pattern was common, although involvement of the small joints has also been adequately reported. The mean number of joints involved in all patients was 3. Axial symptoms and enthesitis were present and often coexistent. Treatment with NSAIDs and intra-articular steroids lead to successful resolution in most cases.

Authors’ contributions

RR: collected patient data and materials, writing-original draft, literature search; AP: collected patient data and materials, review and editing; SM: collected patient data and materials, writing-original draft, DS: collected patient data and materials, writing-original draft, AG: review and editing, AC: collected patient data and materials, conceptualisation, review and editing

Ethics approval

Ethical clearance obtained from Institutional ethical committee (IPGME&R Research Oversight Committee; IPGME&R/IEC/2021/558; dated 28th September, 2021).

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and its online supplementary material.

Sources of funding

No specific funding was received from any bodies in to carry out the work described in this article.

Conflicts of interest

None of the study authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.reuma.2022.03.004.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ramos-Casals M., Brito-Zerón P., Mariette X. Systemic and organ-specific immune-related manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17:315–332. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00608-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.García L.F. Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1441. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh A.K., Misra R., Aggarwal A. Th-17 associated cytokines in patients with reactive arthritis/undifferentiated spondyloarthropathy. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30:771–776. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1646-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokogawa N., Minematsu N., Katano H., Suzuki T. Case of acute arthritis following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-218281. annrheumdis-2020-218281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappello F., Gammazza A.M., Dieli F., de Macario, Macario A.J. Does SARS-CoV-2 trigger stress-inducedautoimmunity by molecular mimicry? A hypothesis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2038. doi: 10.3390/jcm9072038. Published 2020 Jun 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selmi C., Gershwin M.E. Diagnosis and classification of reactive arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:546–549. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valtonen V.V., Leirisalo M., Pentikäinen P.J., Räsänen T., Seppälä I., Larinkari U., et al. Triggering infections in reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1985;44:399–405. doi: 10.1136/ard.44.6.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hannu T., Puolakkainen M., Leirisalo-Repo M. Chlamydia pneumoniae as a triggering infection in reactive arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38:411–414. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parisi S., Borrelli R., Bianchi S., Fusaro E. Viral arthritis and COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e655–e657. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30348-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ono K., Kishimoto M., Shimasaki T., Uchida H., Kurai D., Deshpande G.A., et al. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001350. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2020-001350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waller R., Price E., Carty S., Ahmed A., Collins D. EP01 post COVID-19 reactive arthritis. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020;4(Suppl. 1):rkaa052. Published 2020 Nov 3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jali I. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19 infection. Cureus. 2020;12:e11761. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11761. Published 2020 Nov 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coath F.L., Mackay J., Gaffney J.K. Axial presentation of reactive arthritis secondary to COVID-19 infection. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:e232–e233. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liew I.Y., Mak T.M., Cui L., Vasoo S., Lim X.R. A case of reactive arthritis secondary to coronavirus disease 2019 infection. J Clin Rheumatol. 2020;26:233. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000001560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saricaoglu E.M., Hasanoglu I., Guner R. The first reactive arthritis case associated with COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021;93:192–193. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Danssaert Z., Raum G., Hemtasilpa S. Reactive arthritis in a 37-year-old female with SARS-CoV2 infection. Cureus. 2020;12:e9698. doi: 10.7759/cureus.9698. Published 2020 Aug 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fragata I., Mourão A.F. Coronavirus Disease 19 (COVID-19) complicated with post-viral arthritis. Acta Reumatol Port. 2020;45:278–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasparotto M., Framba V., Piovella C., Doria A., Iaccarino L. Post-COVID-19 arthritis: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:3357–3362. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05550-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hønge B.L., Hermansen M.F., Storgaard M. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:e241375. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-241375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kocyigit B.F., Akyol A. Reactive arthritis after COVID-19: a case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:2031–2039. doi: 10.1007/s00296-021-04998-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schenker H.M., Hagen M., Simon D., Schett G., Manger B. Reactive arthritis and cutaneous vasculitis after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021;60:479–480. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Carlo M., Tardella M., Salaffi F. Can SARS-CoV-2 induce reactive arthritis? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39(Suppl. 128):25–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Hasbani G., Jawad A., Uthman I. Axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis triggered by sars-cov-2 infection: a report of two cases. Reumatismo. 2021;73:59–63. doi: 10.4081/reumatismo.2021.1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sureja N.P., Nandamuri D. Reactive arthritis after SARSCoV-2 infection. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021;5:rkab001. doi: 10.1093/rap/rkab001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shokraee K., Moradi S., Eftekhari T., Shajari R., Masoumi M. Reactive arthritis in the right hip following COVID-19 infection: a case report. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2021;7:18. doi: 10.1186/s40794-021-00142-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gibson M., Sampat K., Coakley G. A self-limiting symmetrical polyarthritis following COVID-19 infection. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghauri I.G., Mukarram M.S., Ishaq K., Riaz S.U. Post COVID19 reactive arthritis: an emerging existence in the spectrum of musculoskeletal complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep. 2020;7:101. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zacharias H., Dubey S., Koduri G., D’Cruz D. Rheumatological complications of Covid 19. Autoimmun Rev. 2021;20:102883. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2021.102883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieper J., van der Heijde D., Landewé R., Brandt J., Burgos-Vagas R., Collantes-Estevez E., et al. New criteria for inflammatory back pain in patients with chronic back pain: a real patient exercise by experts from the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:784–788. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ciaffi J., Meliconi R., Ruscitti P., Berardicurti O., Giacomelli R., Ursini F. Rheumatic manifestations of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Rheumatol. 2020;4:65. doi: 10.1186/s41927-020-00165-0. Published 2020 Oct 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and its online supplementary material.