Abstract

This comparative analysis examines the trajectory of depression severity among patients treated with intravenous ketamine or intranasal esketamine in a clinical setting.

Although intravenous racemic ketamine has rapid antidepressant properties, it is not approved for depression treatment.1 However, the US Food and Drug Administration has approved intranasal esketamine for treatment-resistant depression.1 Correia-Melo et al2 treated 63 participants with intravenous ketamine or esketamine and observed that esketamine was noninferior to ketamine. A recent meta-analysis suggested that intravenous ketamine was more effective,3 but the only head-to-head trial included was from Correia-Melo et al,2 rendering interpretation difficult. To our knowledge, no multidose, head-to-head comparisons of these treatments have been reported.

The Yale Interventional Psychiatry Service (IPS) provides both intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes) and intranasal esketamine (56 or 84 mg). Patients receive similar care with comparable protocols in the same physical space. We analyzed Yale IPS clinical data to evaluate these treatments in a clinical setting.

Methods

For this comparative analysis, we reviewed retrospective data for all Yale IPS patients receiving intravenous ketamine or intranasal esketamine between September 2016 and April 2021 (eMethods in the Supplement). The Yale Institutional Review Board approved this analysis of existing clinical data and waived informed consent per the Common Rule. The analysis followed the ISPOR reporting guideline.

Results

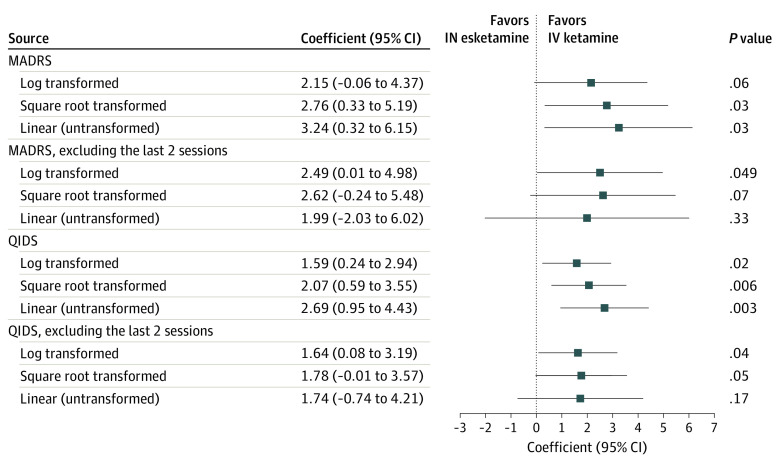

Of 210 included patients, 129 (61.4%) received intravenous ketamine and 81 (38.6%) received intranasal esketamine. There were no differences in baseline demographic factors (Table). The estimated group difference in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) score by treatment end (primary outcome) was 2.15 (95% CI, −0.06 to 4.37; P = .06). Estimated group differences in Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR) scores after full treatment course and MADRS and QIDS-SR scores after the first 6 treatments (secondary outcomes) were 1.59 (95% CI, 0.24-2.94; P = .02), 2.49 (95% CI, 0.01-4.98; P < .05), and 1.64 (0.08-3.19; P = .04), respectively, all favoring intravenous ketamine (Figure). Other models produced similar results. There were no group differences in response rates (37.8% [95% CI, 30.0%-46.3%] vs 36.0% [95% CI, 25.9%-47.5%]) or remission (29.6% [95% CI, 22.5%-37.9%] vs 24.0% [95% CI, 15.6%-35.0%]) for ketamine vs esketamine, respectively.

Table. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of Study Participantsa.

| Characteristic | Treatment | Total (N = 210) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketamine (n = 129) | Esketamine (n = 81) | |||

| Age, y, mean (SD) | 49.9 (16.4) | 46.7 (17.1) | 48.7 (16.7) | .19 |

| Sexb | ||||

| Male | 46 (35.7) | 38 (46.9) | 84 (40.0) | .11 |

| Female | 83 (64.3) | 43 (53.1) | 126 (60.0) | |

| Racec | ||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | .13 |

| Asian | 3 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) | |

| Black or African American | 1 (0.8) | 3 (3.7) | 4 (1.9) | |

| White | 123 (95.4) | 76 (93.8) | 199 (94.8) | |

| Ethnicityc | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 4 (3.1) | 3 (3.7) | 7 (3.3) | .84 |

| Non-Hispanic | 117 (90.7) | 75 (92.6) | 192 (91.4) | |

| Health insurance | ||||

| Private | 96 (74.4) | 59 (72.8) | 155 (73.8) | .27 |

| Public | 17 (13.2) | 16 (19.8) | 33 (15.7) | |

| No. of acute sessions, mean (SD) | 5.79 (1.49) | 7.47 (1.46) | 6.44 (1.69) | NAd |

| Completed prescribed acute coursee | 109 (84.5) | 69 (85.2) | 178 (84.8) | .89 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Data were collected at the Yale Interventional Psychiatry Service (IPS) of the Yale New Haven Health System from September 2016 to April 2021. Values are presented as the number (%) of participants unless indicated otherwise. There was a small amount of missing data for race (3 [1.4%]), ethnicity (11 [5.2%]), and health insurance (22 [10.5%]); including these data in an “unknown” category does not alter the χ2 results, suggesting that these data were missing at random.

Sex is based on categorization documented in the electronic medical records.

Race and ethnicity are based on categorizations documented in the electronic medical records. These data were included because there was a notable difference in race and ethnicity compared with the population served by Yale IPS. Additional studies are needed to identify and address accessibility issues.

For intravenous ketamine, the total number of treatments offered as part of the acute course has changed over the years included in the study, whereas esketamine always consisted of an 8-treatment course. As such, a comparison of the mean number of sessions completed is not appropriate.

Defined as multiple treatments each 7 days apart or less.

Figure. Estimated Differences of Groups Treated With Intravenous Ketamine or Intranasal Esketamine.

Patients received intravenous (IV) ketamine (0.5 mg/kg over 40 minutes) or intranasal (IN) esketamine (56 or 84 mg) to treat depression. Their depression trajectories were assessed using scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) and the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR).

There were no group differences for intravenous ketamine vs intranasal esketamine in mean (SD) suicidal ideation scores on MADRS item 10 (3.03 [1.46] to 1.33 [1.11] vs 2.64 [1.26] to 1.26 [1.24]) and QIDS-SR item 12 (1.44 [0.93] to 0.50 [0.76] vs 1.23 [1.02] to 0.45 [0.74]). Subgroup analysis of 46 patients aged 65 years or older showed response and remission rates of 32.6% (95% CI, 19.5%-48.0%) and 30.4% (95% CI, 17.7%-45.8%), respectively, with no group differences.

Discussion

This comparative analysis evaluating the trajectory of depression severity with ketamine and esketamine yielded no significant differences between groups based on the primary outcome measure. However, secondary outcomes based on QIDS-SR scores after 8 treatments and MARDS and QIDS-SR scores comparing the first 6 treatments all favored intravenous ketamine. There were no differences in response or remission rates, although dichotomizing continuous outcomes inevitably reduces statistical power.4 These findings suggest a trajectory of improvement in favor of intravenous ketamine, although this should be interpreted with utmost caution given the study limitations.

Response and remission rates, while within the range reported in the literature,5,6 were lower than those of other reports. This could be because the Yale IPS functions as a tertiary referral center, resulting in a more severely ill, treatment-resistant patient population.

We did not detect significant between-group differences based on available demographic factors. However, the study demographics may not be representative of the general population, suggesting accessibility issues with these treatments. Identifying and addressing factors related to access is paramount and requires further attention.

This study’s limitations include the nonrandomized nature of treatment allocation and the retrospective nature of the analysis. Ratings were unblinded and conducted in a clinical rather than research setting. Furthermore, the acute course duration for intravenous ketamine was not the same during the entire course of the study. Although both treatments reduce symptoms, these findings signal a potential difference that could be attributable to many factors, including dosing, delivery mechanism, role of arketamine, or patient expectations. A randomized trial is needed to determine the comparative efficacy of these treatments.

eMethods

References

- 1.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47(4):351-354. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00230-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Correia-Melo FS, Leal GC, Vieira F, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive therapy using esketamine or racemic ketamine for adult treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, double-blind, non-inferiority study. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:527-534. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahji A, Vazquez GH, Zarate CA Jr. Comparative efficacy of racemic ketamine and esketamine for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:542-555. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altman DG, Royston P. The cost of dichotomising continuous variables. BMJ. 2006;332(7549):1080. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7549.1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai H, Jain F, Foster S, et al. Long-term outcome in outpatients with depression treated with acute and maintenance intravenous ketamine: a retrospective chart review. J Affect Disord. 2020;276:660-666. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.07.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McInnes LA, Qian JJ, Gargeya RS, DeBattista C, Heifets BD. A retrospective analysis of ketamine intravenous therapy for depression in real-world care settings. J Affect Disord. 2022;301:486-495. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.12.097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods