Abstract

Comparative PCR amplification of small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene (rDNA) sequences indicates substantial preferential PCR amplification of pJP27 sequences with korarchaeote-specific PCR primers. The coamplification of a modified SSU rDNA sequence can be used as an internal standard to determine the amount of a specific SSU rDNA sequence.

Recently a group of deep-branching archaea of considerable phylogenetic interest have been identified on the basis of their small-subunit (SSU) rRNA gene (rDNA) sequence from the Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park, Wyo. (1a, 2, 11). A mixed culture taken from the Obsidian Pool, which contains pJP27 as well as other archaea, has been established in a chemostat in the laboratory (6, 12).

The presence of pJP27 in the laboratory culture has been determined by phylogenetic staining (8) and PCR amplification of the SSU rDNA sequences by using korarchaeote-specific probes and primers (6, 12). The initial sequences of the PCR-amplified SSU rDNAs identified pJP27, but not pJP78, among the PCR products; however, specific PCR amplification reported here indicates pJP78 is also present in the chemostat culture. Although both phylogenetic staining and PCR amplification indicate the presence of korarchaeotes in the chemostat culture, they give dramatically different estimates of the relative amounts of these organisms in the chemostat.

In this study we establish that the pJP27 SSU rDNA sequence is preferentially amplified relative to other SSU rDNA sequences found in the chemostat culture derived from the Obsidian Pool. We also are able to determine the abundance of the korarchaeote SSU rDNA sequences by using a modified SSU rDNA sequence as an internal standard. This approach also allows the determination of the abundance of specific SSU rDNA sequences from environmental or laboratory samples.

Cells from the chemostat culture were harvested and DNA was prepared as previously described (1). PCR amplification of the SSU rDNA sequences in the DNA preparation was performed with various primer sets (Table 1) and a standard PCR protocol: 90 s at 96°C; 10 cycles of 30 s at 96°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 60 s at 72°C; 25 cycles of 20 s at 94°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 60 s (increased by 2 s each cycle) at 72°C; and 600 s at 72°C. All enzyme digestions and cloning (pAMP1; Gibco-BRL, Eggenstein, Germany) were performed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The SacII restriction sites of pJP27 and pJP78 SSU rDNA sequences were converted to PstI or EcoRI, respectively, with modified PCR primers (Pst-F, 5′-GCC AGC CGC TGC AGT AAA ACC-3′; Pst-R, 5′-GGT TTT ACT GCA GCG GCT GGC-3′; EcoR-F, 5′-GCC AGC CGC CGA ATT CAA ACC AGC-3′; and EcoR-R, 5′-GCT GGT TTG AAT TCG GCG GCT GGC-3′).

TABLE 1.

PCR primer setsa

| Primer set | Forward primerb | Reverse primerc |

|---|---|---|

| L | 23F | 1390R |

| T | 236F | 1146R |

| C | 384F | 890aR |

| F | 624F | 1390R |

| R | 23F | 604R |

| A | 236F | 890aR |

| B | 384F | 1146R |

| Q | 533F | 1146R |

| K | 236F | 1390R |

| J | 23F | 1146R |

| W | 624F | 1146R |

| X | 797aF | 1146R |

The primer numbers refer to the position in the Escherichia coli SSU rRNA sequence (4). For cloning, linkers appropriate for the pAMP1 vector system (Gibco-BRL) were added to the primers.

Forward primers and their sequences are as follows (references are given parenthetically): 23F, 5′-TCY GGT TGA TCC TGC C-3′ (9); 236F, 5′-GAG GCC CCA GGR TGG GAC CG-3′ (8); 384F, 5′-CTC CGC AAT RCG CGM AAG-3′ (5); 533F, 5′-TGB CAG CMG CCG CGG TAA-3′ (7); 624F, 5′-GTT AAA TCC GCC TGA AGA CA-3′ (5); and 797aF, 5′-GCR AAS SGG ATT AGA TAC CC-3′ (7).

The amount of pJP27 or pJP78 SSU rDNA sequence present in a DNA sample was determined by coamplifying a known amount of the appropriate modified SSU rDNA sequence along with the SSU rDNA sequences in the DNA sample and analyzed following endonuclease restriction enzyme digestion by agarose gel electrophoresis. The gels were documented and the files were analyzed with NIH Image 1.62b7 software.

In an initial PCR characterization of the organisms present in the chemostat established from the Obsidian Pool, roughly one-third of the sequences were identical to the pJP27 sequence (12), but pJP78 was not detected, although a few pJP78 sequences were detected in the Barns et al. characterization of the Obsidian Pool (1a, 2). These results create a conundrum, as phylogenetic staining suggests that pJP27 is a minor component, possibly as low as 1 in 104 cells (6). This disparity between the microscopic observations and the PCR analysis suggests that some of the SSU rDNA sequences may be preferentially PCR amplified. Thus, the relative PCR amplification of pJP27 and pJP78 using korarchaeote-specific primers (set T) was examined.

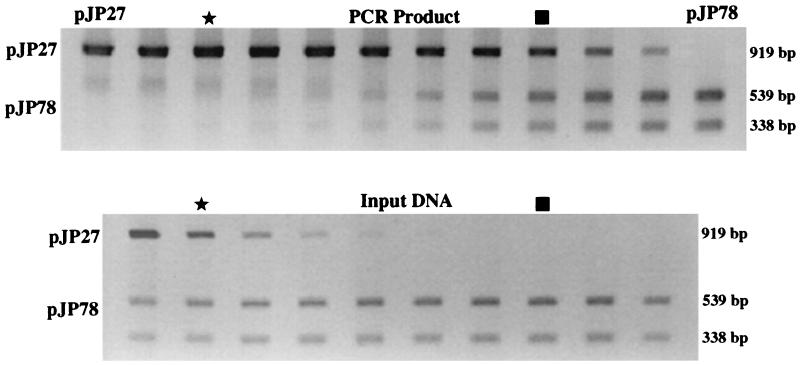

The T primers are virtually a perfect match to both the pJP27 and pJP78 sequences (pJP27 has a single mismatch in the 5′ end of the reverse primer). As shown in Fig. 1, when the pJP78 plasmid exceeds the pJP27 plasmid by 65-fold in the target DNA, equal amounts of pJP27 and pJP78 PCR products are produced. This preferential amplification is clearly associated with the sequence between the primer binding sites rather than simply with the primer binding sites themselves, as a similar preferential PCR amplification is observed with plasmid or PCR product. The addition of 5% acetamide to the PCR has previously been observed to alleviate the differential amplification (17); however, acetamide did not significantly affect the preferential amplification of pJP27 relative to pJP78.

FIG. 1.

Dilution series in which the ratio of pJP78 target increases relative to the pJP27 target by twofold in each lane. The lower panel displays the target DNAs (PCR product of a previous amplification), and the upper panel displays the PCR product following amplification using T primers. Stars indicate the lanes in which the sequences are in equal amounts in the target, while squares indicate the lanes in which the sequences are in equal amounts in the PCR product. Scanning analysis of these gels indicates that the PCR products are equal in amounts when the pJP78 target exceeds the pJP27 target by 65-fold.

When other primer sets are examined, the differential PCR amplification varies widely. Table 2 lists the ratio of pJP78 to pJP27 target required to produce equal amounts of PCR products for each primer set. Different portions of the pJP27 and pJP78 SSU rDNA sequences are PCR amplified with significantly different efficiencies. Comparative PCR amplification of pJP27 with other SSU rDNA sequences obtained from the chemostat in an earlier analysis (12), using L primers, are also shown in Table 2. Substantial differential amplification is observed among these SSU rDNA sequences as well (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Differential PCR amplification of various regions of the SSU rRNA sequences and SSU rRNAs from different organismsa

| Primer set | Ratio of pJP78/pJP27 target required to produce equal amounts of PCR product |

|---|---|

| W | >300 |

| Q | 200 |

| B | 150 |

| X | 125 |

| J | 100 |

| T | 65 |

| R | 50 |

| L | 4 |

| A | 2 |

| K | 2 |

| F | 1 |

| C | 0.2 |

The targets for all comparisons were PCR products from a PCR amplification using L primers. PCR products of amplifications were analyzed by restriction endonuclease digestion. The pJP78 sequence was provided by the N. Pace laboratory.

TABLE 3.

Relative PCR amplification of the pJP27 SSU rDNA sequence compared with SSU rDNA sequences of different organisms from a previous analysis (12)a

| Sequence compared to pJP27 | Ratio of target/pJP27 required to produce equal amounts of PCR product |

|---|---|

| I-3 | 6 |

| I-9 | 10 |

| II-22 | 3 |

| III-4 | 3 |

| M11TL | 5 |

| pJP78 | 4 |

See the footnote to Table 2 for additional information.

Knowing that there is a significant preferential PCR amplification of pJP27, it is possible that pJP78 is present in the chemostat but is not detected. Within the region spanned by the T primers, pJP27 has a BglI restriction site but pJP78 does not; thus, cleavage with BglI prior to PCR amplification should eliminate intact pJP27. When the DNA was digested with BglI prior to PCR amplification, the pJP78 sequence could be readily detected.

In order to determine the exact amount of korarchaeotes present in a sample, a modified pJP27 SSU rDNA sequence can be used as an internal standard during PCR (3, 10, 13, 14, 16). A single SacII restriction site in pJP27 was modified to a PstI site. When the PCR amplifications of the original and modified pJP27 sequences were compared by using various primers, their amplifications were identical, and the relative amounts of each sequence in the PCR product were easily determined by cleavage with SacII or PstI following the PCR amplification. The reciprocal nature of these analyses significantly increases the accuracy with which the relative abundance of each sequence can be determined. By this assay, DNA prepared from the chemostat contains about 4.7 fg of pJP27 SSU rDNA sequence per ng of total DNA.

A similarly modified pJP78 SSU rDNA sequence was constructed in which the SacII restriction site was converted to an EcoRI site. By using this modified pJP78 sequence and chemostat DNA, extensively digested with BglI to eliminate pJP27 sequences, 0.9 fg of pJP78 SSU rDNA sequence per ng of total DNA was detected.

A direct comparison of the PCR amplification of the SSU rDNA from pJP27 and that of SSU rDNA sequences from other organisms indicates that there is a significant preferential PCR amplification of the pJP27 SSU rDNA sequences. This preferential PCR amplification is a property of the SSU rDNA sequences themselves, not simply the primer binding region. Including a modified sequence as an internal standard which PCR amplifies identically to the unmodified sequence but can be distinguished from the unmodified sequence after amplification by a unique restriction site allows the amount of unmodified sequence in the original sample to be determined.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. O. Stetter for providing laboratory and technical assistance while C.F.B. was a visiting scientist at his laboratory at the University of Regensburg. A clone containing the pJP78 SSU rDNA sequence was kindly provided by the Pace laboratory. We thank Gary Fogel, Jinliang Li, and Erik Avaniss-Aghajani for critical reviews of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to K. O. Stetter.

REFERENCES

- 1.Avaniss-Aghajani E, Jones K, Chapman D, Brunk C. A molecular technique for identification of bacteria using small subunit ribosomal RNA sequences. BioTechniques. 1994;17:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 1a.Barns S M, Fundyga R E, Jeffries M W, Pace N R. Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barns S M, Delwiche C F, Palmer J D, Pace N R. Perspectives on archaeal diversity, theromophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9188–9193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker-André M, Hahlbrock K. Absolute messenger RNA quantification using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR)—a novel approach by a PCR aided transcript titration assay (PATTY) Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:9437–9446. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.22.9437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius J, Dull J T, Sleeter D D, Noller H F. Gene organization and primary structure of a ribosomal RNA operon from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1981;148:107–127. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90508-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burggraf, S. Personal communication.

- 6.Burggraf S, Heyder P, Eis N. A pivotal archaea group. Nature (London) 1997;385:780. doi: 10.1038/385780a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burggraf S, Huber H, Stetter K O. Reclassification of the crenarchaeal orders and families in accordance with 16S rRNA sequence data. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:657–660. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-3-657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burggraf S, Mayer T, Amann R, Schadhauser S, Woese C R, Stetter K O. Identifying members of the domain Archaea with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3112-3119.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burggraf S, Stetter K O, Rouviere P, Woese C R. Methanopyrus kandleri: an archaeal methanogen unrelated to all other known methanogens. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1991;14:346–351. doi: 10.1016/s0723-2020(11)80308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clemente M S, Menzo S, Bagnarelli P, Manzin A, Valenza A, Varaldo P E. Quantitative PCR and RT-PCR in virology. PCR Methods Appl. 1993;2:191–196. doi: 10.1101/gr.2.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doolittle W F. At the core of the Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8787–8799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eis N. Phylogenetische Vielfalt von Archaeen in Anreicherungskulturen aus Vulkangebieten. Diplomarbeit am Lehrstuhl für Mikrobiologie der Universität Regensburg, Germany. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilliland G, Perrin S, Blanchard K, Bunn H F. Analysis of cytokine messenger RNA and DNA—detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2725–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Möller A, Jansson J K. Quantification of genetically tagged cyanobacteria in Baltic Sea sediment by competitive PCR. BioTechniques. 1997;22:512–518. doi: 10.2144/97223rr02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen G J, Lane D J, Giovannoni S J, Pace N R, Stahl D A. Microbial ecology and evolution: a ribosomal approach. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1986;40:337–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.40.100186.002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piatak M, Jr, Luk K-C, Williams B, Lifson J D. Quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction for accurate quantification of HIV DNA and RNA species. BioTechniques. 1993;14:70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reysenbach A-L, Giver L J, Wickham G S, Pace N R. Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3417–3418. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.10.3417-3418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]