Abstract

Objective

To explore the value and potential of qualitative research to neurosurgery and provide insight and understanding to this underused methodology.

Methods

The definition of qualitative research is critically discussed and the heterogeneity within this field of inquiry explored. The value of qualitative research to the field of neurosurgery is articulated through its contribution to understanding complex clinical problems.

Discussion

To resolve some of the misunderstanding of qualitative research, this paper discusses research design choices. We explore approaches that use qualitative techniques but are not, necessarily, situated within a qualitative paradigm in addition to how qualitative research philosophy aids researchers to conduct interpretive inquiry that can reveal more than simply what was said by participants. Common research designs associated with qualitative inquiry are introduced, and how complex analysis may contribute more in-depth insights is explained. Approaches to quality are discussed briefly to support improvements in qualitative methods and qualitative manuscripts. Finally, we consider the future of qualitative research in neurosurgery, and suggest how to move forward in the qualitative neurosurgical evidence base.

Conclusions

There is enormous potential for qualitative research to contribute to the advancement of person-centered care within neurosurgery. There are signs that more qualitative research is being conducted and that neurosurgical journals are increasingly open to this methodology. While studies that do not engage fully within the qualitative paradigm can make important contributions to the evidence base, due regard should be given to immersive inquiry within qualitative paradigms to allow complex, in-depth, investigations of the human experience.

Key words: Methodology, Patient experience, Qualitative research, Research methods

Introduction

This paper explores the value and potential of qualitative research to the field of neurosurgery. We argue that qualitative research is underused and misunderstood, yet including qualitative research in neurosurgical study designs can lead to improved provision of person-centered care. While this paper cannot be a comprehensive review of the many discourses and debates within qualitative research, it does offer insight, understanding, and practical advice.

Background: What Is Qualitative Research, What It Is Not, and Why Conduct Qualitative Research in Neurosurgery?

What Is Qualitative Research?

There is no one way to conduct qualitative research.1 Instead, qualitative research is an umbrella term for a heterogenous field of inquiry.2 While this heterogeneity causes some challenges (see Aspers and Corte3 for a critical discussion of what is qualitative research), broad principles characterize this approach.

Qualitative researchers attempt to understand events and experiences through detailed descriptive and interpretive analysis of people’s experiences, views, perspectives, and perceptions of their social reality. Most commonly (but not exclusively), qualitative studies use in-depth, non-numerical data collection methods to explore participants’ experiences.4 These methods can reveal important insights not possible from research driven by quantitative methods alone.5 There are a number of different definitions that illustrate qualitative research’s core commitments:

…any type of research that produces findings not arrived at by statistical procedures or other means of quantification6

…qualitative research involves an interpretive, naturalistic approach to the world. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or to interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them1

…an iterative process in which improved understanding to the scientific community is achieved by making new significant distinctions resulting from getting closer to the phenomenon studied3

From these definitions, we can extrapolate that qualitative research commonly attempts to make sense of naturally occurring events using approaches that are non-numerical, interpretive, and iterative. However, there are circumstances in which qualitative research is used to understand events that have not occurred naturally, such as their use in experimental designs. Analysis may include numerical data, favor description over interpretation, and proceed in a linear rather than iterative fashion. These diverse approaches, and their application, make the field of qualitative research rich and complex and why a comprehensive review of all qualitative research is beyond the scope of this manuscript.

What Is Not Qualitative Research?

At first glance qualitative studies may appear unscientific or anecdotal.7 Studies with small sample sizes may also bear some resemblance to case reports and case series. However, as a research strategy, rigorous qualitative research remains a systematic form of empirical inquiry based on explicit sampling and in-depth analytical approaches. In contrast, case reports and case series are “publication types” and should never be considered qualitative research.8

Why Conduct Qualitative Research in Neurosurgery?

Simply put, numbers are never enough to completely understand or improve patient care. Not every question can, or should, be answered numerically. Valid measures may be able to identify the presence or absence of an outcome yet do not tell us why these outcomes exist. Furthermore, where there is little, or no, previous understanding of a subject it is simply not possible to have large group interventions or valid questionnaires. It is here, within the “unknown,” that qualitative research finds its voice and is a powerful tool to understand clinical problems.9

A search for qualitative research in neurosurgical journals specifically is evidence of the underuse of this approach. Restricting the neurosurgical evidence base in this way may have a detrimental effect on advancing patient care because different neurosurgical research questions need different research designs.10 Qualitative studies make an important contribution to evidence-based practice and neurosurgery is no exception. In an editorial in the Journal of Neurosurgery, Khu and Midha11 call for more qualitative research to understand the patient perspective:

The use of qualitative research in total avulsion brachial plexus injuries (BPIs) fills a void not addressed or explored by quantitative research. Clinicians are mostly concerned about treatment options and outcomes, but little has been written about the patient perspective of the disease. […], it is imperative that we understand the condition from the patient’s standpoint to help them make informed decisions about their treatment.11

Examples of recent qualitative studies include exploring patient perceptions of neurosurgery, medical errors, communication and decision making. In addition to neurosurgeons’ perspectives on long-term follow-up and their ability to conduct and disseminate clinical research (see these and others in Table 1). These studies need an open and curious approach that starts by asking “how and why” not “if and how many.”12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Table 1.

Neurosurgical Topics and Research Aims Examined in Studies Using Qualitative Methods

| Topic | Research aim |

|---|---|

| Neurosurgical patient experiences |

|

| Neurosurgical patient attitudes and perceptions |

|

| Neurosurgical patient decision-making |

|

| Neurosurgical patient education |

|

| Neurosurgical patient information needs |

|

| Neurosurgical careers |

|

| Neurosurgical research capacity |

|

| Neurosurgical decision making |

|

| Neurotrauma long-term follow-up |

|

LMICs, low- and middle-income countries; TBI, traumatic brain injury.

Until more recently the contribution of qualitative research to evidence-based practice, had been viewed as less valuable than evidence generated through statistical measurement.25,26 Despite this, a bibliometric and altmetric comparison of the impact of qualitative and quantitative research concluded that both had similar academic impact.27 Furthermore, a qualitative study on the effects of deep brain stimulation on the lived experience of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients28 has been viewed more than 8000 times, with 80 downloads and 54 citations (metrics obtained from Scopus).

There is therefore evidence that qualitative research is valued and is increasingly published.27,29 However, there is some concern that qualitative research is not well understood in medical journals and some well-conducted research papers are being rejected.30 This paper aims to reduce this knowledge gap by discussing design choice and quality in qualitative studies.

Discussion: How to Design Qualitative Neurosurgical Research

Having established that qualitative research is valuable in neurosurgery the discussion now attends to the question of how to design qualitative neurosurgical research. Qualitative research extends beyond the mere collection of qualitative data and associated techniques31 (methods) to the application of these techniques within a qualitative paradigm (methodology). The distinction between qualitative methods and qualitative methodology is important and has been referred to as small q versus big Q.31,32 While this distinction may be too binary to reflect the heterogeneity within the field of qualitative inquiry, it is useful to think about studies that are designed to simply use qualitative techniques but are not overly concerned with qualitative thinking, and those which engage fully with qualitative theory and use this to enhance their research design. For example, researchers may want to know more about patient acceptability of a neurosurgical intervention while participating in a randomized control trial. Researchers in this study may value the quantification of relevant themes or concepts to answer their research question. In contrast, researchers may want to understand the lived experience of surviving severe head injury. This research is more likely to value in-depth interpretive themes to answer the research question, relying less on quantification and more on meaning, and as such be designed within a qualitative paradigm. These researchers will need to have discussions about the nature of reality and knowledge (i.e., ontology and epistemology) during the design of their research as these decisions will shape the research design. These decisions should be explicit in protocol development and the associated manuscript for publication.

Selecting a Research Design

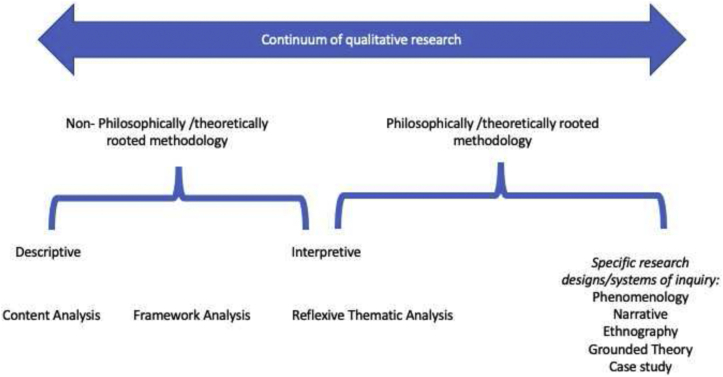

As a heterogenous field of inquiry, there are a large number of qualitative research designs (see Figure 1; however, we recognize this figure is incomplete, and that many authors would reject a restrictive typology). On the left are approaches not necessarily anchored by philosophy or theory (although it is important to note that some say research without theory is impossible because no study can be designed without some influence or guiding interest).33,34 In contrast on the right are those firmly anchored in their own epistemological and ontological world views. These designs are often, but not always, associated with more complex and sensitive analysis and will by that nature take longer to complete. However, these appear to be less common in the medical literature.

Figure 1.

Continuum of qualitative research.

Designs on the left are thematic approaches most closely aligned to quantitative principles, describing the patterns in the data through counting the presence of certain features of interest. Therefore, these studies often retain their foothold in (post)positivist assumptions and rely heavily on rigid procedures, coding frames, and inter-rater reliability of coding decisions.35 Examples include content and framework analysis; however, there are also ways of conducting these studies that adopt a more interpretive stance. Such studies tend to be more common in the medical literature.

Another popular thematic approach is the method described by Braun and Clarke,36 which has now been cited more than 90,000 times. However, this proliferation has led to some dubious qualitative studies that present little of the analytical rigor required of this approach. To counteract this misrepresentation, Braun and Clarke37 more recently labeled their approach as “reflexive thematic analysis” to emphasize the subjectivity and reflexivity that is central to its interpretive stance. Reflexivity in qualitative research is defined as: The process of critical self-reflection about oneself as researcher (own biases, preferences, preconceptions), and the research relationship (relationship to the respondent, and how the relationship affects participant’s answers to questions).38 Therefore, reflexive thematic analysis is situated within the center of the continuum to illustrate its roots in a qualitative paradigm but its freedom from specific ontological and epistemological anchors.35

To help differentiate these research approaches, Table 2 provides some hypothetical neurosurgical research questions and the nature of the findings achieved using these different designs.39,40 On the right-hand side of Figure 1 are highly interpretive designs that do have specific ontological and epistemological anchors. The “big five” are phenomenology, narrative, ethnography, grounded theory, and case study (not to be confused with case reports or case series; case study methodology involves complex systematic analysis, multiple forms of data and are an explicit qualitative design).8 There also others including discourse analysis, conversation analysis and action research. While there are some commonalities, these are all very different and have specific methods to support complex in-depth, and interpretive, analysis41 (see Table 3 and Creswell and Poth49 for a useful comparative text).6,42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48

Table 2.

Comparison of Qualitative Research Approaches

| Qualitative Research Design | Main Focus of Inquiry | Common Subdivisions | Example Question | Nature of the Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content analysis | Determine the presence of items of interest within the data set | Conceptual/relational Conventional/directed/summative |

What are the specific discharge concerns of children with hydrocephalus? | Descriptive or interpretive themes with an emphasis on quantification. |

| Framework analysis | How does an a priori theory explain the study data? | Five-stage analysis protocol.39 Seven-stage analysis protocol.40 |

Patient perspectives on risk-taking behavior leading to head injury. | Understanding of what can, and cannot, be explained by current theory. |

| Reflexive thematic analysis37 | In-depth, reflexive interpretation of the data. | N/A | Women’s experiences of becoming a neurosurgeon. | In-depth interpretive themes. |

N/A, not available.

Table 3.

Comparison of Qualitative Research Approaches (Cont.)

| Qualitative Research Design | Main Focus of Inquiry | Common Subdivisions | Example Question | Nature of the Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenomenology | The essence of experience | Descriptive; interpretive; interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA)42 | What is the lived experience of neurosurgeons during the COVID-19 pandemic? | In-depth understanding of the individual experience. |

| Narrative | Exploring the individual life story | The ‘what’ of a story; The ‘how’ of a story Biographical43; life story; oral history, Labovian44 |

How do patients live with, and make sense of, neurological disability post-neurosurgery? | Individual stories, life courses, sense making, identity, relationships. |

| Ethnography | Cultural interpretation | Realist, critical, rapid, case study | What are the working practices of staff in a neurosurgical department? | Understanding of practice, behavior, attitudes and how these contribute to the resultant culture. |

| Grounded theory | Developing theory | Classical45; Straussian6; constructivist46 | How do patients adjust to acute ward settings following discharge from neurocritical care? | Generation or discovery of theory/explanation. |

| Case study | Examination of a bounded system | Intrinsic; instrumental; collective47 Descriptive; explanatory; exploratory48 |

How do neurocritical care departments implement and evaluate new neurosurgical guidelines? | In-depth understanding of the key facets within a system and the barriers and facilitators driving change. |

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Quality in Qualitative Research

Given the range of qualitative approaches strategies to increase quality in qualitative studies should be commensurate with the chosen design and its associated philosophy. For example, a study using phenomenological inquiry should not be forced to use procedures more appropriate for a content analysis (or vice versa). Furthermore, the field of qualitative inquiry is constantly evolving and views evolve with it. For example, the “reliability” of analysis, where participants and researchers reach the same conclusions, may have been previously prioritized through checking the accuracy of coding decisions and interpretations, member checking, respondent validation and peer review. In contrast, emphasis has more recently been given to using these methods to advance interpretation rather than check analysis to reach a more meaningful conclusion.30

Despite this ongoing dialogue, there are common strategies that can improve the quality of qualitative research (Table 4). These techniques should be discussed during protocol development. Some studies will use very few of these, others will use many; unfortunately, some will use none. However, all qualitative studies should employ some strategies to improve quality. The choice of which and why should be informed by the research question, methodology and philosophical position of the study. In addition, the 32-item Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ)50 also can help researchers to develop a robust protocol. Understanding what should be reported in a qualitative manuscript, before the study is conducted, can improve its quality and subsequent impact.

Table 4.

Strategies to Increase Quality in Qualitative Research

| Domain | Strategy | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility | Prolonged engagement | Long interviews and/or observations Longitudinal designs Multiple data collection points |

| Triangulation of data and methods | Multiple sources of data, multiple researchers, multiple methods | |

| Member checking | Returning data to participants to check accuracy | |

| Respondent validation | Checking interpretation of data with participants and building responses into the analytical process | |

| Expertise | Consultation/supervision from a qualitative expert Evidence of qualitative training |

|

| Peer debriefing | Sharing of analysis with peers to sense check meaningful interpretation | |

| Dependability and confirmability | Audit trail | Clarity of methods and procedural rigor reported in a study. Transparency of process involved to analyze data from codes to findings |

| Authenticity | Present raw data in the form of direct quotes Ensure participants are fairly represented, i.e., do not overly rely on quotes from one person Findings are well grounded and supportable |

|

| Transferability | Thick description | Contextual/demographic information for participants Provision of rich detailed quotes |

| Reflexivity | Diary | Maintain a reflexive diary and use in the analytical process |

The Future of Qualitative Research in Neurosurgery

Table 5 suggests a number of contemporary neurosurgical research questions where a qualitative approach would make a valuable contribution to the evidence base. However, there are many others and neurosurgeons are encouraged to explore how qualitative studies may advance their own professional practice and patient care.

Table 5.

Contemporary Neurosurgical Qualitative Research

| Subspeciality | Future Research Areas |

|---|---|

| General neurosurgery |

|

| Functional |

|

| Paediatric |

|

| Vascular |

|

| Spine |

|

| Oncology |

|

| Trauma |

|

| Peripheral nerve |

|

| COVID-19 |

|

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

While qualitative research is finding its place within the neurosurgical evidence-base, this brings with it an opportunity to harmonize the contrasting epistemological and ontological positions that has led to their historical separation and years of debate known as the “paradigm wars.”51 There is a rich opportunity to mute the differences between these and design more mixed methods studies where qualitative methods are used to enhance understanding reached through quantitative analysis. That said, reducing qualitative research to a procedural variation52 that prioritizes method over methodology has been criticized. For example, studies that use a few direct quotes to support a P value limit the contribution of qualitative research. It is argued that by improving understanding of high-quality qualitative research, we can open up the possibility of genuine mixed methodology that draws the best that both types of research can offer.

We would also encourage more studies that engage fully in the philosophical and theoretical complexities of qualitative inquiry. Such studies lend themselves to more complex and nuanced interpretations of the lived experience. However, to achieve this, methodological knowledge must be grown to ensure neurosurgical qualitative research continues to develop in a way that is commensurate with this field of inquiry. Commitment should also be made to the time that such complex investigations necessitate.

Beyond neurosurgery, qualitative inquiry continues to advance. While traditionally, qualitative researchers have prioritized in-person data collection, the pandemic has seen researchers flock to online methods and digital data collection. In addition, research which engages communities and works with participants as co-investigators is seen as a powerful and emancipatory approach. A method gaining popularity is PhotoVoice that asks participants to share their lived experience through photography.53 We should also follow with interest the progress of rapid approaches to qualitative research. Rapid approaches can be useful for time sensitive projects but are not without their critics.54 Furthermore, as the qualitative evidence base grows so does the opportunity to conduct systematic reviews of qualitative evidence, qualitative evidence synthesis, and meta-synthesis (a somewhat distant cousin of meta-analysis). These are increasingly contributing to recommendations from the World Health Organization and other practice guidelines answering questions that go beyond feasibility and acceptability.55 For an example of a recent meta-synthesis see Whiffin et al.56 that examined the subjective experiences of families following traumatic brain injury in adult populations in the sub/post-acute period. This was a complex, and lengthy study. In contrast, in the context of the current pandemic a rapid approach to qualitative evidence synthesis enabled Houghton et al.57 to quickly influence policy and practice regarding adherence to infection prevention and control guidelines.

Recommendations

To aid neurosurgeons to conduct qualitative research we offer a number of recommendations and practical solutions (Box 1). In addition to these, we also recommend scoping review is conducted to understand more fully the contribution of qualitative research to the neurosurgical evidence base.

Box 1. Recommendations.

| • Design studies that are inclusive of qualitative methods to advance understanding of patient perspectives during quantitative studies such as clinical trials. |

| • Develop standalone qualitative studies that are not framed within a quantitative investigation and commit to in-depth, interpretive, exploratory analysis and the time this requires. |

| • Ask more complex qualitative research questions and embrace more advanced qualitative methodologies. |

| • Discuss qualitative research with others, talk about methods and methodology, reflect on the strengths and limitations of different approaches. |

| • Consult a qualitative expert for guidance, advice, and mentorship. |

| • Visit neuroqual.org for open-access qualitative resources for neurosurgeons and neurosurgery developed by members of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma and follow up-dates on Twitter (@Neuro_Qual) and LinkedIn (@Neuroqual). |

Conclusions

There is enormous potential for qualitative research to contribute to the advancement of patient care within neurosurgery. There are signs that more qualitative research is being conducted and published. However, we must improve knowledge and increase understanding of the quality in qualitative inquiry. Furthermore, while studies that pay little attention to the interpretive lens in qualitative research make an important contribution to the evidence base, due regard should be given to immersive inquiry within qualitative paradigms to allow complex, in-depth, investigations of the human experience.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Charlotte J. Whiffin: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. Brandon G. Smith: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Santhani M. Selveindran: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Tom Bashford: Writing – review & editing. Ignatius N. Esene: Writing – review & editing. Harry Mee: Writing – review & editing. M. Tariq Barki: Writing – review & editing. Ronnie E. Baticulon: Writing – review & editing. Kathleen J. Khu: Writing – review & editing. Peter J. Hutchinson: Writing – review & editing. Angelos G. Kolias: Writing – review & editing.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research, United Kingdom Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma project 16/137/105. A.G.K. and P.J.H. are supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma. P.J.H. is also supported by a NIHR Research Professorship and the Royal College of Surgeons of England, United Kingdom. The NIHR Global Health Research Group on Neurotrauma was commissioned by the United Kingdom NIHR using Official Development Assistance funding (Project No. 16/137/105). Drs. Esene, Baticulon, and Kolias are members of the Young Neurosurgeons Committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies. The committee is supporting this project.

The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the United Kingdom National Health Service, NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- 1.Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/toc/ecip053/2004026085.html Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2005. Table of contents. Available at:

- 2.Saldana J. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2011. Fundamentals of Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aspers P., Corte U. What is qualitative in qualitative research. Qual Sociol. 2019;42:139–160. doi: 10.1007/s11133-019-9413-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaismoradi M., Turunen H., Bondas T. Content analysis and thematic analysis: implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nurs Health Sci. 2013;15:398–405. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beuving J., de Vries G. Amsterdam University Press; Amsterdam: 2015. Doing Qualitative Research: The Craft of Naturalistic Inquiry. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strauss A.L., Corbin J.M. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1990. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green J., Britten N. Qualitative research and evidence-based medicine. BMJ. 1998;316:1230–1232. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7139.1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alpi K.M., Evans J.J. Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type. J Med Libr Assoc. 2019;107:1–5. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2019.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuper A., Reeves S., Levinson W. An introduction to reading and appraising qualitative research. BMJ. 2008;337:a288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esene I.N., El-Shehaby A.M., Baeesa S.S. Essentials of research methods in neurosurgery and allied sciences for research, appraisal and application of scientific information to patient care (Part I) Neurosci Riyadh. 2016;21:97–107. doi: 10.17712/nsj.2016.2.20150552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khu K.J., Midha R. Editorial: Qualitative research in brachial plexus injury. J Neurosurg. 2015;122:1411–1412. doi: 10.3171/2014.5.JNS141012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifford W., Sharpe H., Khu K.J., Cusimano M., Knifed E., Bernstein M. Gamma Knife patients’ experience: lessons learned from a qualitative study. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:387–392. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9830-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bramall A., Djimbaye H., Tolessa C., Biluts H., Abebe M., Bernstein M. Attitudes toward neurosurgery in a low-income country: a qualitative study. World Neurosurg. 2014;82:560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernstein M., Potvin D., Martin D.K. A qualitative study of attitudes toward error in patients facing brain tumour surgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2004;31:208–212. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100053841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khu K.J., Bernstein M., Midha R. Patients’ perceptions of carpal tunnel and ulnar nerve decompression surgery. Can J Neurol Sci. 2011;38:268–273. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100011458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khu K.J., Doglietto F., Radovanovic I., et al. Patients’ perceptions of awake and outpatient craniotomy for brain tumor: a qualitative study. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:1056–1060. doi: 10.3171/2009.6.JNS09716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feler J., Tan A., Sammann A., Matouk C., Hwang D.Y. Decision making among patients with unruptured aneurysms: a qualitative analysis of online patient forum discussions. World Neurosurg. 2019;131:e371–e378. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2019.07.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison J.D., Seymann G., Imershein S., et al. The impact of unmet communication and education needs on neurosurgical patient and caregiver experiences of care: a qualitative exploratory analysis. World Neurosurg. 2019;122:e1528–e1535. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozmovits L., Khu K.J., Osman S., Gentili F., Guha A., Bernstein M. Information gaps for patients requiring craniotomy for benign brain lesion: a qualitative study. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9955-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bandyopadhyay S., Moudgil-Joshi J., Norton E.J., Haq M., Saunders K.E.A., NANSIG Collaborative Motivations, barriers, and social media: a qualitative study of uptake of women into neurosurgery. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2020.1849555 [e-pub ahead of print]. Br J Neurosurg. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Whiffin C.J., Smith B.G., Esene I.N., et al. Neurosurgeons’ experiences of conducting and disseminating clinical research in low-income and middle-income countries: a reflexive thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e051806. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granek L., Shapira S., Constantini S., Roth J. Pediatric neurosurgeons’ philosophical approaches to making intraoperative decisions when encountering an uncertainty or a complication while operating on children. https://doi.org/10.3171/2020.12.PEDS20912 [e-pub ahead of print]. J Neurosurg Pediatr. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Smith B.G., Whiffin C.J., Esene I.N., et al. Neurotrauma clinicians’ perspectives on the contextual challenges associated with long-term follow-up following traumatic brain injury in low-income and middle-income countries: a qualitative study protocol. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e041442. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AANS Neurosurgeon Seeing the Humanity in Neurosurgery through Qualitative Research. 2019. https://aansneurosurgeon.org/aansstudent/seeing-the-humanity-in-neurosurgery-through-qualitative-research/ Available at:

- 25.Greenhalgh T., Annandale E., Ashcroft R., et al. An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ. 2016;352:i563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loder E., Groves T., Schroter S., Merino J.G., Weber W. Qualitative research and the BMJ. BMJ. 2016;352:i641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Retrouvey H., Webster F., Zhong T., Gagliardi A.R., Baxter N.N. Cross-sectional analysis of bibliometrics and altmetrics: comparing the impact of qualitative and quantitative articles in the British Medical Journal. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e040950. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Haan S., Rietveld E., Stokhof M., Denys D. Effects of deep brain stimulation on the lived experience of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients: in-depth interviews with 18 patients. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0135524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuval K., Harker K., Roudsari B., et al. Is qualitative research second class science? A quantitative longitudinal examination of qualitative research in medical journals. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenhalgh T. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2014. How to Read a Paper: The Basics of Evidence-Based Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braun V., Clarke V. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kidder L.H., Fine M. Qualitative and quantitative methods: When stories converge. New Dir Program Eval. 1987;35:57–75. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwandt T.A. In: Theory and Concepts in Qualitative Research. Flinders D.J., Mills G.E., editors. Teachers College Press; New York: 1993. Theory for the moral sciences; crisis of identity and purpose. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merriam S.B. 3rd ed. Jossey-Bass; Hoboken, NJ: 2009. Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun V., Clarke V., Weate P. In: Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. Smith B., Sparkes A.C., editors. Taylor & Francis (Routledge); Oxfordshire: 2016. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Braun V., Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korstjens I., Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pr. 2018;24:120–124. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ritchie J., Spencer L. In: Analyzing Qualitative Data. Bryman A., Burgess R.G., editors. Routledge; Oxfordshire: 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ng S.L., Baker L., Cristancho S., Tara J., Kennedy T.J., Lingard L. In: Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice. 3rd ed. Swanwick T., Forrest K., O’Brien B.C., editors. Wiley Blackwell; New York: 2019. Qualitative research in medical education: methodologies and methods. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith J.A., Flowers P., Larkin M.H. SAGE; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wengraf T. Short Guide to BNIM. 2008. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/id/eprint/30/ Available at:

- 44.Labov W., Waletzky J. Narrative analysis: oral versions of personal experience. J Narrat Life Hist. 1997;7:3–38. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glaser B.G. Aldine; Venice: 1967. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charmaz K. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stake R.E. In: Handbook of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed. Denzin N.K., Lincoln Y.S., editors. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. Case studies. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yin R.K. 2nd ed. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Creswell J.W., Poth C.N. 4th ed. SAGE Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2018. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bryman A. In: The SAGE Handbook of Social Research Methods. Alasuutari P., Bickman L., Brannen J., editors. SAGE Publications Ltd; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. The end of the paradigm wars. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith J.K., Heshusius L. Closing down the conversation: the end of the quantitative-qualitative debate among educational inquirers. Educ Res. 1986;15:4–12. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halvorsrud K., Eylem O., Mooney R., Haarmans M., Bhui K. Identifying evidence of the effectiveness of photovoice: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the international healthcare literature. J Public Health Oxf. 2021:fdab074. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdab074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thorne S. Metasynthetic madness: what kind of monster have we created? Qual Health Res. 2017;27:3–12. doi: 10.1177/1049732316679370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Booth A., Noyes J., Flemming K., Moore G., Tuncalp O., Shakibazadeh E. Formulating questions to explore complex interventions within qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(suppl 1):e001107. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Whiffin C.J., Gracey F., Ellis-Hill C. The experience of families following traumatic brain injury in adult populations: a meta-synthesis of narrative structures. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;123:104043. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Houghton C., Meskell P., Delaney H., et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;4:CD013582. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]