In 2019, 4777 youth died of a drug overdose in the United States.1 Seven-hundred and twenty-seven youth died of overdoses involving benzodiazepines (BZDs) and 902 from overdoses involving psychostimulants.2 Opioid-related overdose deaths frequently involve other substances, and in youth, stimulants and BZDs are the most commonly involved substances.3 Overdoses can involve prescription drugs accessed through medical prescriptions or through illicit means. Among persons aged 18 to 25 years, 5.8% report past-year prescription stimulant misuse and 3.8% prescription BZD misuse.4

To inform overdose prevention efforts, we determined how often youth with medically treated overdoses involving BZDs and stimulants had recent BZD or stimulant prescriptions.

Methods

We included youth (15–24 years) from the MarketScan commercial claims database who experienced an overdose involving stimulants or BZDs (January 01, 2016 to December 31, 2018). MarketScan covers privately insured individuals and captures diagnoses and procedures from inpatient and outpatient visits and dispensed prescriptions.5 Overdose events treated in an emergency department (ED) or inpatient setting were included, defined using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes for an unintentional, intentional, or undetermined poisoning initial encounter (Table 1). Stimulant overdoses were limited to overdoses involving amphetamine or methylphenidate. We selected the first overdose per person and required ≥6 months of insurance enrollment with prescription coverage before the overdose.

TABLE 1.

Previous Prescriptions in Youth (15–24 y) With a Medically-Treated Overdose Involving a BZD, 2016–2018

| Overdoses Involving BZDs | N = 2986 | Intent of Overdoses Involving BZDsa | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intentional (n = 1664) | Unintentional (n = 1160) | |||

| Age at overdose, y, median (IQR) | 20 (17–22) | 20 (18–22) | 20 (18–22) | |

| Female, n (%) | 1556 (52.1) | 1045 (62.8) | 447 (38.5) | <.001 |

| Mental health diagnosis in previous 6 mo,b n (%) | 2232 (74.7) | 1300 (78.1) | 813 (70.1) | <.001 |

| Previous BZD prescription,c n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 mo | 854 (28.6) | 590 (35.5) | 234 (20.2) | <.001 |

| 0–6 mo | 1243 (41.6) | 850 (51.1) | 348 (30.0) | <.001 |

| Days from overdose to most recent prescription, median (IQR) | 16 (5–39) | 16 (5–37) | 15 (4–40) | |

| Subset with BZD prescription(s) in previous 6 mo | N = 1243 | n = 850 | n = 348 | |

| Number of BZD fills, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 2 (1–4) | 3 (1–5) | |

| >3 fills dispensed, n (%) | 470 (37.8) | 300 (35.3) | 156 (44.8) | .002 |

| Total BZD d supplied, median (IQR) | 60 (30–120) | 60 (30–120) | 73 (30–136) | |

| >90 d dispensed, n (%) | 413 (33.2) | 267 (31.4) | 134 (38.5) | .018 |

| Mental health diagnosis in previous 6 mo,b n (%) | 1153 (92.8) | 785 (92.4) | 324 (93.1) | .653 |

ICD-10-CM overdose definitions: overdose involving BZD: T42.4 × 1A, T42.4 × 2A, T42.4 × 4A. Previous BZD prescriptions identified through records of dispensed prescriptions before overdose event: alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, clonazepam, clorazepate, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, quazepam, temazepam, triazolam. BZD, benzodiazepine; IQR: interquartile range.

Undetermined overdose events not displayed (N = 162); if multiple overdose codes were recorded with differing intents (intentional, unintentional, undetermined), precedence in classification was given to intentional then unintentional.

Mental health diagnoses identified in 6 mo before overdose event (excluding date of overdose event): International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM: 290–319; ICD-10-CM: F01–F99; see Supplemental Table 3 for specific diagnoses.

Prescription anytime in previous 0 to 12 mo: overall: 1380 (46.2%), intentional: 923 (55.5%), unintentional: 407 (35.1%).

In the 6 months before the overdose, we identified dispensed BZD and stimulant prescriptions and mental health diagnoses (Tables 1 and 2). We summed the number of fills and days’ supply for prescriptions dispensed in the 6 months before the overdose. Results were stratified by intentional self-harm versus unintentional overdoses. In a secondary analysis, class of prescription stimulant was considered with whether the overdose involved amphetamine or methylphenidate.

TABLE 2.

Previous Prescriptions in Youth (15–24 y) With a Medically-Treated Overdose Involving a Stimulant, 2016–2018

| Overdoses Involving Stimulants (Amphetamine or Methylphenidate) | N = 971 | Intent of Overdoses Involving Stimulantsa | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intentional (n = 388) | Unintentional (n = 524) | |||

| Age at overdose, y, median (IQR) | 19 (17–22) | 18 (16–20) | 20 (18–22) | |

| Female, n (%) | 415 (42.7) | 213 (54.9) | 179 (34.2) | <.001 |

| Mental health diagnosis in previous 6 mo, n (%)b | 634 (65.3) | 299 (77.1) | 299 (57.1) | <.001 |

| Previous stimulant prescription,c n (%) | ||||

| 0–1 mo | 239 (24.6) | 137 (35.3) | 93 (17.7) | <.001 |

| 0–6 mo | 380 (39.1)d | 219 (56.4) | 147 (28.1) | <.001 |

| Days from overdose to most recent prescription, median (IQR) | 20 (8–47) | 21 (9–47) | 14 (5–46) | |

| Subset with stimulant prescription in previous 6 mo | N = 380 | n = 219 | n = 147 | |

| Number of stimulant fills, median (IQR) | 4 (2–5) | 3 (2–5) | 4 (2–6) | |

| >3 fills dispensed, n (%) | 191 (50.3) | 102 (46.6) | 83 (56.5) | .064 |

| Total stimulant days supplied, median (IQR) | 120 (60–180) | 117 (60–150) | 120 (90–180) | |

| >90 d dispensed, n (%) | 213 (56.1) | 112 (51.1) | 95 (64.6) | .011 |

| Mental health diagnosis in previous 6 mo, n (%) | 335 (88.2) | 199 (90.9) | 123 (83.7) | .038 |

ICD-10-CM overdose definitions: overdose involving stimulant: amphetamine (T43.621A, T43.622A, T43.624A) and methylphenidate (T43.631A, T43.632A, T43.634A). Previous stimulant prescriptions identified through records of dispensed prescriptions before overdose event: amphetamines (amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, lisdexamfetamine, methamphetamine) and methylphenidates (methylphenidate, dexmethylphenidate). Mental health diagnoses identified in 6 mo before overdose event (excluding date of overdose event): International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM): 290-319; ICD-10-CM: F01-F99; see Supplemental Table 4 for specific diagnoses. IQR, interquartile range.

Undetermined overdose events not displayed (N = 59); if multiple overdose codes were recorded with differing intents (intentional, unintentional, undetermined), precedence in classification was given to intentional then unintentional.

Mental health diagnoses identified in 6 mo before overdose event (excluding date of overdose event): ICD-9-CM: 290–319; ICD-10-CM: F01–F99; see Supplemental Table 4 for specific diagnoses.

Prescription anytime in previous 0 to 12 mo: overall: 416 (42.8%), intentional: 238 (61.3%), unintentional: 162 (30.9%).

Overdose by type: overdose involving amphetamine (n = 833), 31.8% have amphetamine prescription in previous 6 mo; overdose involving methylphenidate (n = 146), 64.4% have methylphenidate prescription in previous 6 mo.

Results

We identified 2986 youth who experienced an overdose involving BZDs and 971 youth with an overdose involving stimulants (amphetamine or methylphenidate). The majority of youth had a previous mental health diagnosis; 56% of overdoses involving BZDs were intentional compared to 40% of overdoses involving stimulants (Table 1).

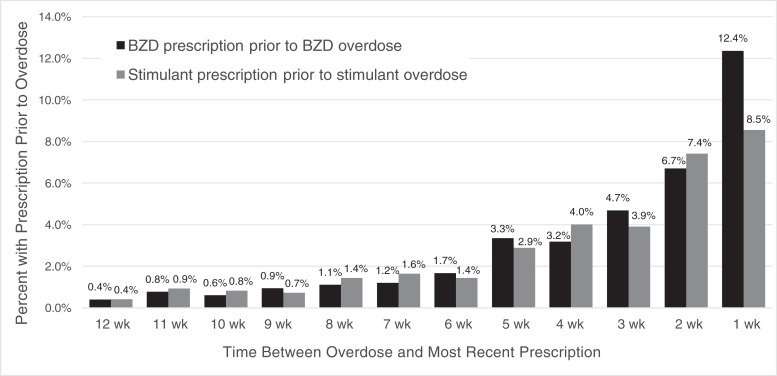

Twenty-nine percent of youth with overdoses involving BZDs had a prescription BZD dispensed in the previous 30 days and 42% in the previous 6 months (Table 1, Fig 1). Among youth with a BZD prescription in the previous 6 months, 33% received >90 days’ supply, and 73% had an anxiety disorder diagnosis (Supplemental Table 3). Youth with intentional BZD overdoses were more likely to have a recent BZD prescription (51%) than those with unintentional overdoses (30%).

FIGURE 1.

Proportion of youth (15–24 years) with a prescription fill* before an overdose involving a benzodiazepine or stimulant by time between prescription and overdose. BZD, benzodiazepine. *Percent with BZD prescription before an overdose involving a BZD; percent with stimulant prescription before an overdose involving amphetamine or methylphenidate.

A quarter of youth with an overdose involving stimulants (amphetamine/methylphenidate) had a stimulant prescription dispensed in the previous 30 days and 39% in the previous 6 months (Table 2, Fig 1). Among youth with a stimulant prescription in the previous 6 months, 56% received >90 days’ supply and 71% had an ADHD diagnosis (Supplemental Table 4). Youth with intentional stimulant overdoses were more likely to have a recent stimulant prescription (56%) than those with unintentional overdoses (28%).

Discussion

A considerable fraction of youth with overdoses involving BZDs and stimulants had recent prescriptions for these drugs. Previous BZD and stimulant prescriptions were more common in youth with intentional overdoses. This underscores the importance of incorporating self-injury assessment into clinical practice for youth prescribed BZDs and stimulants and highlights the need for differing prevention efforts for intentional and unintentional youth overdoses.

The majority of youth who received a BZD or stimulant prescription before overdose had a mental health diagnosis. These medications are prescribed for mental health problems common in youth6,7 and can be effective treatments. However, because these drugs are commonly misused4 and involved in overdoses, weighing risks and benefits when prescribing them remains imperative.

Primary considerations of this research include that we cannot distinguish amphetamine overdoses related to prescription amphetamine versus an illicit substance. We miss overdoses that did not present to the ED or hospital, including fatal overdoses occurring outside these settings, and events in which BZD or stimulant involvement was not recorded. Without comparator groups, we are unable to assess comparative overdose liability by prescription characteristics.

Given that one-fourth of youth who overdose on these drugs receive prescriptions for them in the previous month, results suggest an avenue of prevention and motivate future work examining overdose risk after prescription. Because the potential for harm with BZD and stimulants increases with selected combinations of prescription medications, alcohol, and illicit drugs, and especially concurrent BZD and opioid use,8,9 these concerns warrant attention and discussion at prescription initiation.

Supplementary Material

Glossary

- BZD

benzodiazepine

- ED

emergency department

- IQR

interquartile range

- ICD-9-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

- ICD-10-CM

International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification

Footnotes

Dr Bushnell made substantial contributions to the conception and design, analysis, and interpretation of data, drafted the initial manuscript, and revised the manuscript; Drs Samples, Calello, Gerhard, and Olfson made substantial contributions to the design and interpretation of data and critically revised and reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FUNDING: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Bethesda, MD) under Award 1K01DA050769-01A1. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control . WISQARS: Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed October 18, 2021

- 2. CDC, National Center for Health Statistics . Wide-ranging online data for epidemiologic research (WONDER). Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov. Accessed October 18, 2021

- 3. Lim JK, Earlywine JJ, Bagley SM, Marshall BDL, Hadland SE. Polysubstance involvement in opioid overdose deaths in adolescents and young adults, 1999–2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):194–196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20-07-01-001, NSDUH Series H-55). 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 5. IBM Watson Health . IBM MarketScan research databases for health services researchers. Available at: https://www.ibm.com/downloads/cas/6KNYVVQ2. Accessed July 22, 2020

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Data and statistics on children’s mental health. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmental-health/data.html. Accessed October 15, 2021

- 7. Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, et al. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A). Psychol Med. 2012;42(9): 1997–2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sharma V, Simpson SH, Samanani S, Jess E, Eurich DT. Concurrent use of opioids and benzodiazepines/Z-drugs in Alberta, Canada and the risk of hospitalisation and death: a case cross-over study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e038692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xu KY, Hartz SM, Borodovsky JT, Bierut LJ, Grucza RA. Association between benzodiazepine use with or without opioid use and all-cause mortality in the United States, 1999–2015. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12): e2028557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.